Salt of the Earth(1954 film)

| Salt of the Earth | |

|---|---|

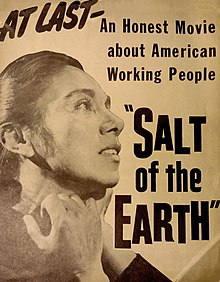

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Herbert J. Biberman |

| Screenplay by | Michael Wilson |

| Produced by | Paul Jarrico |

| Starring |

|

| Cinematography |

|

| Edited by |

|

| Music by | Sol Kaplan |

| Distributed by | Independent Productions |

Release date |

|

Running time | 94 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Languages | English Spanish |

| Budget | $250,000 |

Salt of the Earthis a 1954 Americandrama filmwritten byMichael Wilson,directed byHerbert J. Biberman,and produced byPaul Jarrico.All had beenblacklistedby theHollywoodestablishmentdue to their alleged involvement incommunistpolitics.[1]

The drama film is one of the first pictures to advance thefeministsocial and political point of view. Its plot centers on a long and difficultstrike,based on the1951 strikeagainst theEmpire Zinc CompanyinGrant County, New Mexico.In the film, the company is identified as "Delaware Zinc", and the setting is "Zinctown, New Mexico". The film shows how the miners, the company, and the police react during the strike. Inneorealiststyle, the producers and director used actual miners and their families as actors in the film.[2]In 1992, the film was added to theNational Film Registry.

Plot

[edit]

Esperanza Quintero is a miner's wife in Zinc Town,New Mexico,a community which is essentially run and owned by Delaware Zinc Inc. Esperanza is thirty-five years old, pregnant with her third child and emotionally dominated by her husband, Ramón Quintero.[3]We know from her concern about her onomásticos or día de mi/su santo orName Daythat it is the 12th November as that is the onomásticos of persons named Esperanza.

The majority of the miners areMexican-Americansand want decent working conditions equal to those of white, or "Anglo"miners. Theunionizedworkers go on strike, but the company refuses to negotiate and the impasse continues for months. Esperanza gives birth and, simultaneously, Ramón is beaten by police and jailed on bogus assault charges following an altercation with a union worker who betrayed his fellows. When Ramón is released, Esperanza tells him that he's no good to her in jail. He counters that if the strike succeeds they will not only get better conditions right now but also win hope for their children's futures.[4]

The company presents aTaft-Hartley Actinjunction to the union, meaning any miners who picket will be arrested. Taking advantage of a loophole, the wives picket in their husbands' places. Some men dislike this, seeing it as improper and dangerous. Esperanza is forbidden to picket by Ramón at first, but she eventually joins the line while carrying her baby.[5]

The sheriff, by company orders, arrests the leading women of the strike. Esperanza is among those taken to jail. When she returns home, Ramón tells her the strike is hopeless, as the company will easily outlast the miners. She insists that the union is stronger than ever and asks Ramón why he can't accept her as an equal in their marriage. Both angry, they sleep separately that night.[6]

The next day the company evicts the Quintero family from their house. The union men and women arrive to protest the eviction. Ramón tells Esperanza that they can all fight together. The mass of workers and their families proves successful in saving the Quinteros' home. The company admits defeat and plans to negotiate. Esperanza believes that the community has won something no company can ever take away and it will be inherited by her children.[7]

Cast

[edit]Professional actors

|

Non-professional actors

|

|

|

Production

[edit]

The film was called 'subversive' and blacklisted because theInternational Union of Mine, Mill and Smelter Workerssponsored it and many blacklisted Hollywood professionals helped produce it. The union had been expelled from theCIOin 1950, over the alleged domination of its leadership bycommunists.[8]

Director Herbert Biberman was one of the Hollywood screenwriters and directors who refused to answer theHouse Committee on Un-American Activitiesin 1947 on questions of affiliation to theCommunist Party USA.TheHollywood Tenwere cited and convicted forcontempt of Congressand jailed. Biberman was imprisoned in theFederal Correctional InstitutionatTexarkanafor six months. After his release he directed this film.[9]Other participants who made the film and were blacklisted by the Hollywood studios include: Paul Jarrico, Will Geer, Rosaura Revueltas, and Michael Wilson.[citation needed]

The producers cast only five professional actors. The rest were locals fromGrant County, New Mexico,or members of the International Union of Mine, Mill and Smelter Workers, Local 890, many of whom were part of the strike that inspired the plot. Juan Chacón, for example, was in real life a union local president. In the film he plays theprotagonist,who has trouble dealing with women as equals.[10]The director was reluctant to cast him at first, thinking he was too "gentle", but both Revueltas and the director's sister-in-law, Sonja Dahl Biberman, wife of Biberman's brotherEdward,urged him to cast Chacón as Ramón.[11]

The film was denounced by theUnited States House of Representativesfor its communist sympathies, and theFBIinvestigated the film's financing. TheAmerican Legioncalled for a nationwideboycottof the film. After its opening night in New York City, the film languished for 10 years because all but 12 theaters in the country refused to screen it.[12]

By one journalist's account: "During the course of production inNew Mexicoin 1953, the trade press denounced it as a subversive plot,anti-Communistvigilantes fired rifle shots at the set, the film's leading lady Rosaura Revueltas was deported to Mexico, and from time to time a small airplane buzzed noisily overhead... The film, edited in secret, was stored for safekeeping in an anonymous wooden shack in Los Angeles. "[13]

Reception

[edit]Critical response

[edit]

With McCarthyism in full force at the time of release, the Hollywood establishment did not embrace the film.[14]

Pauline Kael,who reviewed the film forSight and Soundin 1954, panned it as a simplistic left-wing "morality play" and said it was "as clear a piece of Communistpropagandaas we have had in many years. "[15]

Bosley Crowther,film critic forThe New York Times,reviewed the picture favorably, both for its screenplay and direction, writing: "In the light of this agitated history, it is somewhat surprising to find thatSalt of the Earthis, in substance, simply a strong pro-labor film with a particularly sympathetic interest in the Mexican-Americans with whom it deals....But the real dramatic crux of the picture is the stern and bitter conflict within the membership of the union. It is the issue of whether the women shall have equality of expression and of strike participation with the men. And it is along this line of contention that Michael Wilson's tautly muscled script develops considerable personal drama, raw emotion and power. "Crowther called the film" a calculated social document ".[16]Michael Wilson, who worked under anom de plumefor some years afterwards, later won an Academy Award for the screenplay ofBridge on the River Kwai(1957).[17]

The review aggregatorRotten Tomatoesreported that 100% of critics gave the film a positive review, based on eleven reviews.[18]

Accolades

[edit]- Karlovy Vary International Film Festival:Best Actress: Rosaura Revueltas;Crystal GlobeAward for Best Picture, Herbert J. Biberman, receivedEx aequoalso byTrue Friends.Karlovy Vary(Carlsbad),Czechoslovakia;1954.[19]

- Academie du Cinema de Paris: International Grand Prize; 1955.[20]

- In 1992, theLibrary of Congressselected the film for preservation in the United StatesNational Film Registryfor being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant."[21]

- The film is preserved by theMuseum of Modern Artin New York City.

Later history

[edit]

The film found an audience in bothWesternandEastern Europein the few years after its American release.[22]The story of the film's suppression, as well as the events it depicted, inspired anundergroundaudience of unionists, leftists,feminists,Mexican-Americans,andfilm historians.The film found a new life in the 1960s and gradually reached larger audiences through union halls, women's associations, andfilm schools.The 50th anniversary of the film saw a number of commemorative conferences held across theUnited States.[23]

Around 1993,Massachusetts Institute of Technologylinguistics professor and political commentatorNoam Chomskypraised the film because of the way people were portrayed doing the real work of unions. According to Chomsky: "[T]he real work is being done by people who are not known, that's always been true in every popular movement in history...I don't know how you get that across in a film. Actually, come to think of it, there are some films that have done it. I mean, I don't see a lot of visual stuff, so I'm not the best commentator, but I thoughtSalt of the Earthreally did it. It was a long time ago, but at the time I thought that it was one of the really great movies—and of course it was killed, I think it was almost never shown. "[24]

The "Salt of the Earth Labor College" located inTucson,Arizonais named after the film. The pro-labor institution (not a collegeper se) holds various lectures and forums related to unionism and economic justice. The film is screened on a frequent basis.[25]

Other releases

[edit]

On July 27, 1999, a digitally restored print of the film was released inDVDby Organa through Geneon (Pioneer), and packaged with the documentaryThe Hollywood Ten,which reported on the ten filmmakers who were blacklisted for refusing to cooperate with theHouse Un-American Activities Committee(HUAC). This Special Edition with the Hollywood Ten film is still available through Organa at organa.com. In 2004, a budget editionDVDwas released byAlpha Video.Alaserdiscversion was released by theVoyager Companyin 1987 (catalog # VP1005L).[26]

Because the film'scopyrightwas not renewed in 1982,[27]the film is now in thepublic domain.[28][29]

Adaptations

[edit]The film has been adapted into a two-actoperacalledEsperanza(Hope). The labor movement inWisconsinandUniversity of Wisconsin–Madisonopera professorKarlos Mosercommissioned the production. The music was written by David Bishop and thelibrettoby Carlos Morton. The opera premiered inMadison, Wisconsin,on August 25, 2000, to positive reviews.[30]

A documentary titledA Crime to Fit the Punishment,about the making of the film, was released in 1982 and was directed by Barbara Moss and Stephen Mack.[31]

Adrama film,based on the making of the film, was chronicled inOne of the Hollywood Ten(2000). It was produced and directed byKarl Francis,starredJeff GoldblumandGreta Scacchi,and was released in European countries on September 29, 2000.[32]

A fictionalized account of the movie's production featured prominently in theAudibleoriginalpodcastseries,The Big Lie (2022).Based on source material written by Paul Jerrico, the production features voice performances fromJon Hamm,Kate Mara,Ana de la Reguera,Bradley Whitford,John Slattery,Giancarlo Esposito,andDavid Strathairn,and was written byJohn MankiewiczandJamie Napoli.[33][34]

See also

[edit]- The Hollywood Ten,documentary film

- Jencks Act

- Jencks v. United States

- Labor history

- The Ladies Auxiliary of the International Union of Mine Mill and Smelter Workers

References

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^Salt of the Earthat theAFI Catalog of Feature Films.

- ^Notes - TCM.com

- ^Full Synopsis - TCM.com

- ^Full Synopsis - TCM.com

- ^Full Synopsis - TCM.com

- ^Full Synopsis - TCM.com

- ^Full Synopsis - TCM.com

- ^Gross, Linda.Los Angeles Times(via FilmSociety - Tri-Pod web site), film review, July 2, 1976. Accessed: August 17, 2013.

- ^The Hollywood Ten.University of California, BerkeleyLibrary. Document maintained on server by Gary Handman, Head, Media Resources Center. Accessed: August 17, 2013.

- ^University of VirginiaArchived16 October 2006 at theWayback Machine."A Nation of Immigrants", October 26, 1995.

- ^Boisson, Steve.American History(via HistoryNet web site), film article, "Salt of the Earth:The Movie Hollywood Could Not Stop ", February 2002 issue. Accessed: August 18, 2013.

- ^Wake, Bob (2001)."Book review of James J. Lorence'sThe Suppression of Salt of the Earth.".culturevulture.net.Archived fromthe originalon 18 November 2012.

- ^Hockstader, Lee.The Washington Post(via Socialist Viewpoint web site), film article, "Blacklisted Film Restored and Rehabilitated," March 3, 2003. Accessed: August 18, 2013.

- ^Articles - TCM.com

- ^Culture Vulture,ibid.

- ^Crowther, Bosley.The New York Times,film review,"Salt of the EarthOpens at the Grande -- Filming Marked by Violence, "March 15, 1954. Accessed: April 28, 2019.

- ^Articles - TCM.com

- ^Salt of the EarthatRotten Tomatoes.Accessed: November 29, 2009.

- ^8th Karlovy Vary International Film FestivalArchived4 November 2013 at theWayback Machine.kviff.com.

- ^People's Weekly World Newspaper,ibid.

- ^Brief Descriptions and Expanded Essays of National Film Registry Titles | Film Registry | National Film Preservation Board

- ^Waring, RobArchived31 December 2006 at theWayback Machine.Picturing Justice,December 21, 1999.

- ^Pecinovsky, TonyArchived27 September 2007 atarchive.today,People's Weekly World Newspaper,May 22, 2003.

- ^Noam Chomskyinterview with political activists, excerpted fromUnderstanding Power,The New Press, 2002.

- ^Salt of the EarthArchived15 August 2020 at theWayback MachineLabor College web site.

- ^Salt of the Earth Special Edition LaserDisc, Rare LaserDiscs, Criterion LaserDiscs

- ^Larry, Ceplair (2007).The Marxist and the movies: a biography of Paul Jarrico.Lexington, KY:University Press of Kentucky.ISBN9780813173009.OCLC182624495.

- ^Campbell, Christopher (7 January 2012)."10 Great Films Set in New Mexico – For the State's Centennial".IndieWire.Retrieved15 March2018.

- ^Carl R. Weinberg (October 2010)."Salt of the Earth: Labor, Film, and the Cold War"(PDF).Organization of American Historians Magazine of History.Retrieved15 March2018.

- ^Wisconsin Labor History SocietyArchived21 February 2007 at theWayback Machineweb site.

- ^Mimi Rosenberg (7 October 1982)."A Crime To Fit The Punishment: an interview with the filmmakers".Pacifica Radio Archives.Retrieved15 March2018– via Internet Archive.

- ^Holden, Stephen.The New York Times,"Back to an Era of Slurs, Paranoia and Persecution," 11 January 2002. Last accessed: 22 November 2007.

- ^Spangler, Todd (1 June 2022)."Audible Drops Trailer for 'The Big Lie' Podcast Drama Starring Jon Hamm, Set in '50s Hollywood Blacklist Era".Variety.Retrieved21 June2022.

- ^Kleitman, Nathaniel (1950)."The Big Lie".Science.112(2912): 475.Bibcode:1950Sci...112R.475K.doi:10.1126/science.112.2912.475.PMID14781822.S2CID9356643.

Bibliography

[edit]- Lorence, James J. (1 October 1999).The Suppression of Salt of the Earth: How Hollywood, Big Labor, and Politicians Blacklisted a Movie in Cold War America.University of New Mexico Press.ISBN9780826320285.

- Salt of the Earth: The Story of a Film,by Herbert J. Biberman. Harbor Electronic Publishing, New York (2nd edition, 2004): 1965. See:Cineastereview of book&Scott Henkel and Vanessa Fonseca. "Fearless Speech and the Discourse of Civility inSalt of the Earth."Chiricú,vol. 1, no. 1, 2016, pp. 19–38.

Further reading

[edit]- Caballero, Raymond.McCarthyism vs. Clinton Jencks.Norman:University of Oklahoma Press,2019.

External links

[edit]- Salt of the Earthat theAFI Catalog of Feature Films

- Salt of the Earthat Metacritic

- Salt of the EarthatIMDb

- Salt of the EarthatAllMovie

- Salt of the Earthat theTCM Movie Database

- Salt of the Earthsegment atNPR

- Salt of the Eartharticle and references for research by Michael Selig

- Salt of the Earthis available for free viewing and download at theInternet Archive

- Salt of the Earth Recovery Projectwebsite recovering Salt of the Earth

- 1954 films

- 1950s feminist films

- 1954 independent films

- 1950s political drama films

- American black-and-white films

- American independent films

- American political drama films

- Censored films

- Crystal Globe winners

- Film censorship in the United States

- Films about the labor movement

- Films directed by Herbert Biberman

- Films scored by Sol Kaplan

- Films set in mining communities

- Films set in New Mexico

- Films shot in New Mexico

- Films with screenplays by Michael Wilson (writer)

- History of labor relations in the United States

- McCarthyism

- Films about Mexican Americans

- Films about mining

- Films about social realism

- 1950s Spanish-language films

- United States National Film Registry films

- 1954 drama films

- 1950s English-language films

- 1950s American films