Sámi languages

| Sámi | |

|---|---|

| Sami, Saami, Samic | |

| Native to | Finland,Norway,Russia,andSweden |

| Region | Sápmi |

| Ethnicity | Sámi |

Native speakers | (30,000 cited 1992–2013)[1] |

Uralic

| |

Early form | |

| Official status | |

Official language in | Norway;[2][3]recognized as a minority language in several municipalities ofFinlandandSweden. |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-2 | smi |

| ISO 639-3 | Variously:sma–Southernsju–Umesje–Pitesmj–Lulesme–Northernsjk–Kemismn–Inarisms–Skoltsia–Akkalasjd–Kildinsjt–Ter |

| Glottolog | saam1281 |

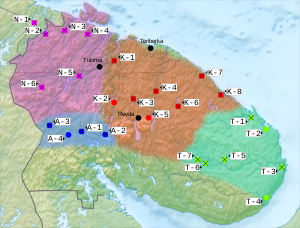

Recent distribution of the Sami languages: 1. Southern Sami, 2. Ume Sami, 3. Pite Sami, 4. Lule Sami, 5. Northern Sami, 6. Inari Sami, 7. Skolt Sami, 8. Kildin Sami, 9. Ter Sami. Striped areas are multilingual or overlapping. | |

Sámi languages(/ˈsɑːmi/SAH-mee),[4]in English also rendered asSamiandSaami,are a group ofUralic languagesspoken by the IndigenousSámipeople inNorthern Europe(in parts of northernFinland,Norway,Sweden,and extreme northwesternRussia). There are, depending on the nature and terms of division, ten or more Sami languages. Several spellings have been used for the Sámi languages, includingSámi,Sami,Saami,Saame,Sámic,SamicandSaamic,as well as theexonymsLappishandLappic.The last two, along with the termLapp,are now often consideredpejorative.[5]

Classification

[edit]The Sámi languages form a branch of theUralic language family.According to the traditional view, Sámi is within the Uralic family most closely related to theFinnic languages(Sammallahti 1998). However, this view has recently been doubted by some scholars who argue that the traditional view of a commonFinno-Samiprotolanguage is not as strongly supported as had been earlier assumed,[6]and that the similarities may stem from an areal influence on Sámi from Finnic.

In terms of internal relationships, the Sámi languages are traditionally divided into the two groups of western and eastern. The groups may be further divided into various subgroups and ultimately individual languages. (Sammallahti 1998: 6-38.) Recently it has been proposed on the basis of (1) different sound substitutions seen between the Sámi languages in the Proto-Scandinavian loanwords and (2) historical phonology that the first unit to branch off from Late Proto-Sámi was Southern Proto-Sámi, from which descend South Sámi, Ume Sámi, and Gävle Sámi (extinct during the 19th century).[7][8]

Parts of the Sámi language area form adialect continuumin which the neighbouring languages may bemutually intelligibleto a fair degree, but two more widely separated groups will not understand each other's speech. There are, however, some sharp language boundaries, in particular betweenNorthern Sami,Inari SamiandSkolt Sami,the speakers of which are not able to understand each other without learning or long practice. The evolution of sharp language boundaries seems to suggest a relative isolation of the language speakers from each other and not very intensive contacts between the respective speakers in the past. There is some significance in this, as the geographical barriers between the respective speakers are no different from those in other parts of the Sámi area.

- Sámi

- Eastern Sámi

- Mainland Eastern Sámi

- Akkala Sámi†

- Inari Sámi(300 speakers)[9]

- Kemi Sámi†

- Kainuu Sámi†

- Skolt Sámi(320 speakers)[10]

- Peninsular Eastern Sámi

- Kildin Sámi(600 speakers)[11]

- Ter Sámi(2 speakers)[12]

- Mainland Eastern Sámi

- Western Sámi

- Central Western Sámi

- Southwestern Sámi

- Southern Sámi(600 speakers)[16]

- Ume Sámi(20 speakers)[17]

- Eastern Sámi

The above figures are approximate.

Geographic distribution

[edit]The Sami languages are spoken inSápmiinNorthern Europe,in a region stretching over the four countriesNorway,Sweden,FinlandandRussia,reaching from the southern part of centralScandinaviain the southwest to the tip of theKola Peninsulain the east. The borders between the languages do not align with the ones separating the region's modern states.

During theMiddle Agesandearly modern period,now-extinct Sami languages were also spoken in the central and southern parts ofFinlandandKareliaand in a wider area on theScandinavian Peninsula.Historical documents as well asFinnishandKarelianoral traditioncontain many mentions of the earlier Sami inhabitation in these areas (Itkonen, 1947). Also,loanwordsas well as place-names of Sami origin in the southern dialects of Finnish and Karelian dialects testify of earlier Sami presence in the area (Koponen, 1996; Saarikivi, 2004; Aikio, 2007). These Sami languages, however, became extinct later, under the wave of the Finno-Karelian agricultural expansion.

History

[edit]TheProto-Sámi languageis believed to have formed in the vicinity of theGulf of Finlandbetween 1000 BC to 700 AD, deriving from a common Proto-Sami-Finnic language (M. Korhonen 1981).[19]However, reconstruction of any basic proto-languages in the Uralic family have reached a level close to or identical toProto-Uralic(Salminen 1999).[20]According to the comparative linguist Ante Aikio, the Proto-Samic language developed in South Finland or in Karelia around 2000–2500 years ago, spreading then to northern Fennoscandia.[21]The language is believed to have expanded west and north intoFennoscandiaduring theNordic Iron Age,reaching centralScandinaviaduring theProto-Scandinavianperiod ca. 500 AD (Bergsland 1996).[22]The language assimilated several strata of unknownPaleo-European languagesfrom the early hunter-gatherers, first during the Proto-Sami phase and second in the subsequent expansion of the language in the west and the north of Fennoscandia that is part of modern Sami today. (Aikio 2004, Aikio 2006).[21][23]

Written languages and sociolinguistic situation

[edit]At present there are nine living Sami languages. Eight of the languages have independent literary languages; the other one has no written standard, and of it, there are only a few, mainly elderly, speakers left. TheISO 639-2code for all Sami languages without their own code is "smi". The eight written languages are:

- Northern Sami(Norway, Sweden, Finland): With an estimated 15,000 speakers, this accounts for probably more than 75% of all Sami speakers in 2002.[citation needed]ISO 639-1/ISO 639-2:se/sme

- Lule Sami(Norway, Sweden): The second largest group with an estimated 1,500 speakers.[citation needed]ISO 639-2:smj

- Ume Sami(Norway, Sweden): likely has under 20 speakers left.ISO 639-2:smu

- Pite Samihas about 30–50 speakers,[24]ISO 639-2:sje

- Southern Sami(Norway, Sweden): 500 speakers (estimated).[citation needed]ISO 639-2:sma

- Inari Sami(Enare Sami) (Inari,Finland): 500 speakers (estimated).[citation needed]SIL code:LPI,ISO 639-2:smn

- Skolt Sami(Näätämö and the Nellim-Keväjärvi districts,Inarimunicipality, Finland, also spoken inRussia,previously in Norway): 400 speakers (estimated).[citation needed]SIL code:LPK,ISO 639-2:sms

- Kildin Sami(Kola Peninsula,Russia): 608 speakers inMurmansk Oblast,179 in other Russian regions, although 1991 persons stated their Saami ethnicity (1769 of them live inMurmansk Oblast)[25]SIL code:LPD,ISO 639-3:sjd

The other Sami languages are critically endangered (moribund,have very few speakers left) or extinct. Ten speakers ofTer Samiwere known to be alive in 2004.[26]The last speaker ofAkkala Samiis known to have died in December 2003,[27]and the eleventh attested variety,Kemi Sami,became extinct in the 19th century. An additional Sami language,Kainuu Sami,became extinct in the 18th century, and probably belonged to the Eastern group like Kemi Sami, although the evidence for the language is limited.

Orthographies

[edit]

Most Sámi languages useLatin alphabets,with these respective additional letters.

Northern Sámi: Áá Čč Đđ Ŋŋ Šš Ŧŧ Žž Inari Sámi: Áá Ââ Ää Čč Đđ Ŋŋ Šš Žž Skolt Sámi: Ââ Čč Ʒʒ ǮǯĐđǦǧ Ǥǥ Ǩǩ Ŋŋ Õõ Šš Žž Åå Ää Lule Sámi (Sweden): Áá Åå Ŋŋ Ää Lule Sámi (Norway): Áá Åå Ŋŋ Ææ Southern Sámi (Sweden): Ïï Ää Öö Åå Southern Sámi (Norway): Ïï Ææ Øø Åå Ume Sámi: Áá Đđ Ïï Ŋŋ Ŧŧ Üü Åå Ää Öö Pite Sámi: Áá Đđ Ŋŋ Ŧŧ Åå Ää

The use of Ææ and Øø in Norway vs. Ää and Öö in Sweden merely reflects the orthographic standards used in theNorwegianandSwedish alphabets,respectively, not differences in pronunciations.

The letter Đ in Sámi languages is a capitalD with a baracross it (Unicodecode point:U+0110), which is also used inSerbo-Croatian,Vietnamese,etc., not the near-identical capitaleth(Ð; U+00D0) used inIcelandic,FaroeseorOld English.

The capital letter Ŋ (eng) is commonly presented in Sámi languages using the "N-form" variant based the usual Latin uppercase N with a hook added.[28]Unicode assigns code point U+014A to the uppercase eng, but does not prescribe the form of the glyph.[29]

The Skolt Sámi standard uses ʹ (U+02B9) as a soft sign,[30]but other apostrophes, such as ' (U+0027), ˊ (U+02CA) or ´ (U+00B4), are also sometimes used in published texts.

TheKildin Sámi orthographyuses the RussianCyrillic scriptwith these additional letters: А̄а̄ Ӓӓ Е̄е̄ Ё̄ё̄ Һһ/ʼ Ӣӣ Јј/Ҋҋ Ӆӆ Ӎӎ Ӊӊ Ӈӈ О̄о̄ Ҏҏ Ӯӯ Ҍҍ Э̄э̄ Ӭӭ Ю̄ю̄ Я̄я̄

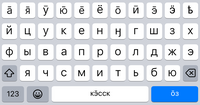

Availability

[edit]In December 2023,Applehas providedon-screen keyboardsfor all eight Sámi languages still spoken (withiOSandiPadOSreleases 17.2), thus enabling Sámi speakers to use their language oniPhonesandiPadswithout restrictions or difficulties.[31]

- Sámi on-screen keyboards on iPhones

-

Pite Sámi(apparently faulty in iOS/iPadOS 17.2, missing đ/ŧ)

The FinnishSFS 5966keyboard standard of 2008[32]is designed for easily typing Sámi languages through use ofAltGranddead diacritic keys.[33]

-

Original SFS-5966 layout; dead diacritic keys in red

Official status

[edit]Norway

[edit]

Adopted in April 1988, Article 110a of theNorwegian Constitutionstates: "It is the responsibility of the authorities of the State to create conditions enabling the Sami people to preserve and develop its language, culture and way of life". The Sami Language Act went into effect in the 1990s. Sámi is an official language alongside Norwegian in the "administrative area for Sámi language", that includes eight municipalities in the northern half of Norway, namelyKautokeino Municipality,Karasjok Municipality,Kåfjord Municipality,Nesseby Municipality,Porsanger Municipality,Tana Municipality,Tysfjord Municipality,Lavangen Municipality,andSnåsa Municipality.[34]In 2005 Sámi,Kven,RomanesandRomaniwere recognised as "regional or minority languages" in Norway within the framework of theEuropean Charter for Regional or Minority Languages.[35]

Sweden

[edit]

On 1 April 2000, Sami became one of five recognizedminority languagesinSweden.[36][37]It can be used in dealing with public authorities inArjeplog Municipality,Gällivare Municipality,Jokkmokk Municipality,andKiruna Municipality.In 2011, this list was enlarged considerably. In Sweden the University of Umeå teaches North, Ume and South Sami, and Uppsala University has courses in North, Lule and South Sami.

Finland

[edit]

InFinland,the Sami language act of 1991 granted the Northern, Inari, and Skolt Sami the right to use their languages for all government services. TheSami Language Act of 2003(Northern Sami:Sámi giellaláhka;Inari Sami:Säämi kielâlaahâ;Skolt Sami:Sääʹmǩiõll-lääʹǩǩ;Finnish:Saamen kielilaki;Swedish:Samisk språklag) made Sami an official language inEnontekiö,Inari,SodankyläandUtsjokimunicipalities.Some documents, such as specific legislation, are translated into these Sami languages, but knowledge of any of these Sami languages among officials is not common. As the major language in the region is Finnish, Sami speakers are essentially always bilingual with Finnish.Language nestdaycares have been set up for teaching the languages to children. In education, Northern Sami, and to a more limited degree, Inari and Skolt Sami, can be studied at primary and secondary levels, both as a mothertongue (for native speakers) and as a foreign language (for non-native speakers).

Russia

[edit]InRussia,Sámi has no official status, neither on the national, regional or local level. It is included in the list of Indigenous minority languages. (Kildin) Sami has been taught at theMurmansk State Technical Universitysince 2012; before then, it was taught at theInstitute of the Peoples of the NorthinSaint Petersburg.[citation needed]

See also

[edit]- Sami parliamentsof Finland, Norway, and Sweden

- Norwegianization of the Sámi

- Pre-Finno-Ugric substrate

References

[edit]- ^SouthernatEthnologue(25th ed., 2022)

UmeatEthnologue(25th ed., 2022)

PiteatEthnologue(25th ed., 2022)

LuleatEthnologue(25th ed., 2022)

NorthernatEthnologue(25th ed., 2022)

KemiatEthnologue(25th ed., 2022)

(Additional references under 'Language codes' in the information box) - ^Vikør, Lars S.;Jahr, Ernst Håkon;Berg-Nordlie, Mikkel."språk i Norge"[languages of Norway].Great Norwegian Encyclopedia(in Norwegian Bokmål).Retrieved30 August2020.

- ^Kultur- og kirkedepartementet (27 June 2008)."St.meld. nr. 35 (2007-2008)".Regjeringa.no(in Norwegian Nynorsk).

- ^Laurie Bauer, 2007,The Linguistics Student’s Handbook,Edinburgh

- ^Karlsson, Fred (2008).An Essential Finnish Grammar.Abingdon-on-Thames,Oxfordshire:Routledge.p. 1.ISBN978-0-415-43914-5.

- ^T. Salminen: Problems in the taxonomy of the Uralic languages in the light of modern comparative studies. — Лингвистический беспредел: сборник статей к 70-летию А. И. Кузнецовой. Москва: Издательство Московского университета, 2002. 44–55. AND[1]

- ^Piha, Minerva & Häkkinen, Jaakko 2020: Kantasaamesta eteläkantasaameen - Lainatodisteita eteläsaamen varhaisesta eriytymisestä. Sananjalka 62. [2]

- ^Häkkinen, Jaakko & Piha, Minerva 2023: Kantasaamesta eteläkantasaameen, osa 2 - Äännehistorian todisteita eteläsaamen varhaisesta eriytymisestä. Sananjalka 65.[3]

- ^Saami, InariatEthnologue(25th ed., 2022)

- ^Saami, SkoltatEthnologue(25th ed., 2022)

- ^Saami, KildinatEthnologue(25th ed., 2022)

- ^Saami, TeratEthnologue(25th ed., 2022)

- ^Saami, LuleatEthnologue(25th ed., 2022)

- ^Saami, PiteatEthnologue(25th ed., 2022)

- ^Saami, NorthatEthnologue(25th ed., 2022)

- ^Saami, SouthatEthnologue(25th ed., 2022)

- ^Saami, UmeatEthnologue(25th ed., 2022)

- ^"Mapping SÁMI Languages".Cartography M.Sc.Retrieved2022-04-25.

- ^Korhonen, Mikko 1981: Johdatus lapin kielen historiaan. Suomalaisen kirjallisuuden seuran toimituksia; 370. Helsinki, 1981

- ^:Problems in the taxonomy of the Uralic languages in the light of modern comparative studies. — Лингвистический беспредел: сборник статей к 70-летию А. И. Кузнецовой. Москва: Издательство Московского университета, 2002. 44–55.

- ^abAikio, Ante (2004). "An essay on substrate studies and the origin of Saami". In Hyvärinen, Irma; Kallio, Petri; Korhonen, Jarmo (eds.).Etymologie, Entlehnungen und Entwicklungen: Festschrift für Jorma Koivulehto zum 70. Geburtstag.Mémoires de la Société Néophilologique de Helsinki. Vol. 63. Helsinki: Société Néophilologique. pp. 5–34.

- ^Knut Bergsland:Bidrag til sydsamenes historie, Senter for Samiske Studier Universitet i Tromsø 1996

- ^Aikio, A. (2006).On Germanic-Saami contacts and Saami prehistory.Journal de la Société Finno-Ougrienne 91: 9–55.

- ^According to researcher Joshua Wilbur and Pite Sami dictionary committee leader Nils Henrik Bengtsson, March 2010.

- ^Russian Census (2002).Data fromhttp://demoscope.ru/weekly/ssp/rus_nac_02.php?reg=0

- ^Tiuraniemi Olli: "Anatoli Zaharov on maapallon ainoa turjansaamea puhuva mies",Kide6 / 2004.

- ^"Nordisk samekonvensjon: Utkast fra finsk-norsk-svensk-samisk ekspertgruppe, Oppnevnt 13. november 2002, Avgitt 26. oktober 2005"(PDF).20 July 2011. Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 20 July 2011.

- ^"Character design standards - Uppercase for Latin 1: Uppercae Eng".Microsoft Typography documentation.2022-06-09.Retrieved2022-12-16.

- ^Cunningham, Andrew (2004-02-04).Global & local dimensions of emerging community languages support(PDF).VALA2004 12th Biennial Conference and Exhibition. Melbourne, Victoria, Australia. p. 15.Retrieved2022-12-16.

- ^"Documentation for Skolt Sami keyboards".UiT Norgga árktalaš universitehta: Sámi Text-to-Speech project.Archived fromthe originalon 2018-08-16.

- ^"About iOS 17 Updates".Apple Inc.Retrieved2023-12-16.

- ^"New Finnish Keyboard Layout"(PDF).2005-11-30. Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 2016-03-04.

- ^"Suomalainen monikielinen näppäimistökaavio, viimeiseksi tarkoitettu luonnos"(PDF)(in Finnish). 2006-06-20. Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 2011-07-20.

- ^Tromsø positiv til samisk språk,NRK

- ^Minoritetsspråk,Language Council of Norway

- ^Hult, F.M. (2004). Planning for multilingualism and minority language rights in Sweden.Language Policy,3(2), 181–201.

- ^Hult, F.M. (2010). Swedish Television as a mechanism for language planning and policy. Language Problems and Language Planning, 34(2), 158–181.

Sources

[edit]- Fernandez, J. 1997. Parlons lapon. – Paris.

- Itkonen, T. I. 1947. Lapparnas förekomst i Finland. – Ymer: 43–57. Stockholm.

- Koponen, Eino 1996. Lappische Lehnwörter im Finnischen und Karelischen. – Lars Gunnar Larsson (ed.), Lapponica et Uralica. 100 Jahre finnisch-ugrischer Unterricht an der Universität Uppsala. Studia Uralica Uppsaliensia 26: 83–98.

- Saarikivi, Janne 2004. Über das saamische Substratnamengut in Nordrußland und Finnland. –Finnisch-ugrische Forschungen58: 162–234. Helsinki: Société Finno-Ougrienne.

- Sammallahti, Pekka(1998).The Saami Languages: an introduction.Kárášjohka: Davvi Girji OS.ISBN82-7374-398-5.

- Wilbur, Joshua. 2014. A grammar of Pite Saami. Berlin: Language Science Press. (Open access)

External links

[edit]- Ođđasat TV Channel in Sami languages

- On line radio stream in various sami languages

- Introduction to the history and current state of Sami

- Kimberli Mäkäräinen"Sámi-related odds and ends," including 5000+ word vocabulary list

- RistenSámi dictionary and terminology database.

- GiellateknoMorphological and syntactic analysers and lexical resources for several Sami languages

- DivvunProofing tools for some of the Sami languages

- Sámedikki giellastivra– Sami language department of theNorwegian Sami parliament(in Norwegian and Northern Sami)

- Finland–Sámi Language Act

- Sami Language ResourcesAll about Sami Languages with glossaries, scholarly articles, resources

- Álgu database,an etymological database of the Sami languages (in Finnish and North Sámi)

- Sami anthems,Sami anthems in various Sami languages

- [4],TheInternationalein Northern Sami

- [5]An extensive intro to Saami languages and grammar from How To Learn Any Language

- Sámi Dieđalaš Áigečála,the only peer-reviewed journal in Saami languages