Seafood

Seafoodis the culinary name for food that comes from any form ofsea life,prominently includingfishandshellfish.Shellfish include various species ofmolluscs(e.g., bivalve molluscs such asclams,oysters,andmussels).

History

[edit]This sectionneeds additional citations forverification.(July 2021) |

The harvesting, processing, and consuming of seafoods are ancient practices with archaeological evidence dating back well into thePaleolithic.[2][3]Findings in asea caveatPinnacle PointinSouth AfricaindicateHomo sapiens(modern humans) harvested marine life as early as 165,000 years ago,[2]while theNeanderthals,an extinct human species contemporary with earlyHomo sapiens,appear to have been eating seafood at sites along the Mediterranean coast beginning around the same time.[4]Isotopic analysis of the skeletal remains ofTianyuan man,a 40,000-year-oldanatomically modern humanfrom eastern Asia, has shown that he regularly consumed freshwater fish.[5][6]Archaeologyfeatures such asshell middens,[7]discarded fish bones, andcave paintingsshow that sea foods were important for survival and consumed in significant quantities. During this period, most people lived ahunter-gathererlifestyle and were, of necessity, constantly on the move. However, early examples of permanent settlements (though not necessarily permanently occupied), such as those atLepenski Vir,were almost always associated with fishing as a major source of food.

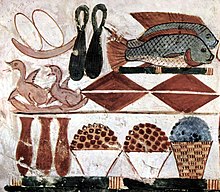

The ancientriverNilewas full of fish; fresh and dried fish were a staple food for much of the population.[8]TheEgyptianshad implements and methods for fishing and these are illustrated intombscenes, drawings, andpapyrusdocuments. Some representations hint at fishing being pursued as a pastime.

Fishing scenes are rarely represented inancient Greekculture, a reflection of the low social status of fishing. However,Oppian of Corycus,a Greek author wrote a major treatise on sea fishing, theHalieulicaorHalieutika,composed between 177 and 180. This is the earliest such work to have survived to the modern day. The consumption of fish varied by the wealth and location of the household. In the Greek islands and on the coast, fresh fish and seafood (squid,octopus,andshellfish) were common. They were eaten locally but more often transported inland.Sardinesandanchovieswere regular fare for the citizens of Athens. They were sometimes sold fresh, but more frequently salted. Asteleof the late 3rd century BCE from the small Boeotian city ofAkraiphia,onLake Copais,provides us with a list of fish prices. The cheapest wasskaren(probablyparrotfish) whereasAtlantic bluefin tunawas three times as expensive.[10]Common salt water fish wereyellowfin tuna,red mullet,ray,swordfish,orsturgeon,a delicacy that was eaten salted. Lake Copais itself was famous in all of Greece for itseels,celebrated by the hero ofThe Acharnians.Other freshwater fish werepike fish,carp,and the less appreciatedcatfish.

Pictorial evidence ofRomanfishing comes frommosaics.[11]At a certain time, thegoatfishwas considered the epitome of luxury, above all because its scales exhibit a bright red colour when it dies out of water. For this reason, these fish were occasionally allowed to die slowly at the table. There even was a recipe where this would take placein Garo,in thesauce.At the beginning of the Imperial era, however, this custom suddenly came to an end, which is why mullusin the feast ofTrimalchio(seetheSatyricon) could be shown as a characteristic of theparvenu,who bores his guests with an unfashionable display of dying fish.

Inmedievaltimes, seafood was less prestigious than other animal meats, and was often seen as merely an alternative to meat on fast days. Still, seafood was the mainstay of many coastal populations.Kippersmade from herring caught in theNorth Seacould be found in markets as far away asConstantinople.[12]While large quantities of fish were eaten fresh, a large proportion was salted, dried, and, to a lesser extent, smoked.Stockfish- cod that was split down the middle, fixed to a pole, and dried - was very common, though preparation could be time-consuming, and meant beating the dried fish with a mallet before soaking it in water. A wide range ofmollusks(includingoysters,musselsandscallops) were eaten by coastal and river-dwelling populations, and freshwatercrayfishwere seen as a desirable alternative to meat during fish days. Compared to meat, fish was much more expensive for inland populations, especially in Central Europe, and therefore not an option for most.[13]

Modern knowledge of the reproductive cycles of aquatic species has led to the development ofhatcheriesand improved techniques offish farmingandaquaculture.A better understanding of thehazardsof eating raw and undercooked fish and shellfish has led to improved preservation methods and processing.

Types of seafood

[edit]The following table is based on the ISSCAAP classification (International Standard Statistical Classification of Aquatic Animals and Plants) used by theFAOto collect and compile fishery statistics.[14]The production figures have been extracted from the FAO FishStat database,[15]and include both capture from wild fisheries and aquaculture production.

| Group | Image | Subgroup | Description | 2010 production 1000 tonnes[15] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| fish | Fishare aquaticvertebrateswhich lacklimbswithdigits,usegillsto breathe, and have heads protected by hardboneorcartilageskulls.See:Fish (food). Total for fish:

|

106,639 | ||

|

marine pelagic |

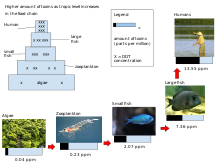

Pelagic fishlive and feed near the surface or in thewater columnof the sea, but not on the bottom of the sea. The main seafood groups can be divided into largerpredator fish(sharks,tuna,billfish,mahi-mahi,mackerel,salmon) and smallerforage fish(herring,sardines,sprats,anchovies,menhaden). The smaller forage fish feed on plankton, and can accumulate toxins to a degree. The larger predator fish feed on the forage fish, and accumulate toxins to a much higher degree than the forage fish. | 33,974

| |

|

marine demersal |

Demersal fishlive and feed on or near the bottom of the sea.[16]Some seafood groups arecod,flatfish,grouperandstingrays.Demersal fish feed mainly on crustaceans they find on the sea floor, and are more sedentary than the pelagic fish. Pelagic fish usually have the red flesh characteristic of the powerful swimming muscles they need, while demersal fish usually have white flesh. | 23,806

| |

| diadromous | Diadromous fishare fishes which migrate between the sea and fresh water. Some seafood groups aresalmon,shad,eelsandlampreys.See:Salmon run. | 5,348

| ||

|

freshwater | Freshwater fishlive inrivers,lakes,reservoirs,andponds.Some seafood groups arecarp,tilapia,catfish,bass,andtrout.Generally, freshwater fish lend themselves tofish farmingmore readily than the ocean fish, and the larger part of the tonnage reported here refers to farmed fish. | 43,511

| |

| molluscs | Molluscs(from the Latinmolluscus,meaningsoft) areinvertebrateswith soft bodies that are not segmented like crustaceans.Bivalvesandgastropodsare protected by acalcareousshellwhich grows as the mollusc grows. Total for molluscs: Total for molluscs:

|

20,797

| ||

|

bivalves | Bivalves,sometimes referred to asclams,have a protective shell in two hinged parts. Avalveis the name used for the protective shell of a bivalve, so bivalve literally meanstwo shells.Important seafood bivalves includeoysters,scallops,musselsandcockles.Most of these arefilter feederswhich bury themselves in sediment on theseabedwhere they are safe frompredation.Others lie on the sea floor or attach themselves to rocks or other hard surfaces. Some, such as scallops, canswim.Bivalves have long been a part of the diet of coastal communities. Oysters wereculturedin ponds by the Romans andmariculturehas more recently become an important source of bivalves for food. | 12,585 | |

|

gastropods | Aquaticgastropods,also known assea snails,are univalves which means they have a protective shell that isin a single piece.Gastropod literally meansstomach-foot,because they appear to crawl on their stomachs. Common seafood groups areabalone,conch,limpets,whelksandperiwinkles. | 526 | |

|

cephalopods | Cephalopods, except fornautilus,are not protected by an external shell. Cephalopod literally meanshead-foots,because they have limbs which appear to issue from their head. They have excellent vision and high intelligence. Cephalopods propel themselves with a water jet and lay down "smoke screens" withink.Examples areoctopus,squidandcuttlefish.They are eaten in many cultures. Depending on the species, the arms and sometimes other body parts are prepared in various ways. Octopus must be boiled properly to rid it of slime, smell, and residual ink. Squid are popular in Japan. In Mediterranean countries and in English-speaking countries squid are often referred to ascalamari.[17]Cuttlefish is less eaten than squid, though it is popular in Italy anddried, shredded cuttlefishis a snack food in East Asia.See:Squid (food)Octopus (food). | 3,653 | |

| other | Molluscs not included above arechitons | 4,033 | ||

| crustaceans | Crustaceans(from Latincrusta,meaningcrust) are invertebrates with segmented bodies protected by hard crusts (shells orexoskeletons), usually made ofchitinand structured somewhat like aknight's armour.The shells do not grow, and must periodically be shed ormoulted.Usually two legs or limbs issue from each segment. Most commercial crustaceans aredecapods,that is they have ten legs, and havecompound eyesset onstalks.Their shell turns pink or red when cooked. Total for crustaceans:

|

11,827 | ||

|

shrimps | Shrimp and prawns,are small, slender, stalk-eyed ten-legged crustaceans with long spinyrostrums.They are widespread, and can be found near the seafloor of most coasts and estuaries, as well as in rivers and lakes. They play important roles in thefood chain.There are numerous species, and usually there is a species adapted to any particular habitat. Any small crustacean which resembles a shrimp tends to be called one.[18]See:shrimp (food),shrimp fishery,shrimp farming,freshwater prawn farming. | 6,917 | |

|

crabs | Crabs are stalk-eyed ten-legged crustaceans, usually walk sideways, and have graspingclawsas their front pair of limbs. They have smallabdomens,shortantennae,and a shortcarapacethat is wide and flat. Also usually included areking crabsandcoconut crabs,even if these belongs to a different group of decapods than the true crabs.See:crab fisheries. | 1,679[19] | |

|

lobsters | Clawed lobstersandspiny lobstersare stalk-eyed ten-legged crustaceans with long abdomens. The clawed lobster has large asymmetrical claws for its front pair of limbs, one for crushing and one for cutting(pictured).The spiny lobster lacks the large claws, but has a long, spiny antennae and a spiny carapace. Lobsters are larger than most shrimp or crabs.See:lobster fishing. | 281[20] | |

|

krill | Krillresemble small shrimp, however they have externalgillsand more than ten legs (swimmingplus feeding and grooming legs). They are found in oceans around the world where theyfilter feedin huge pelagicswarms.[21]Like shrimp, they are an important part of the marine food chain, convertingphytoplanktoninto a form larger animals can consume. Each year, larger animals eat half the estimated biomass of krill (about 600 million tonnes).[21]Humans consume krill in Japan and Russia, but most of the krill harvest is used to makefish feedand for extracting oil. Krill oil contains omega-3 fatty acids, similarly tofish oil.See:Krill fishery. | 215 | |

| other | Crustaceans not included above aregooseneck barnacles,giant barnacle,mantis shrimpandbrine shrimp[22] | 1,359 | ||

| other aquatic animals | Total for other aquatic animals:

|

1409+ | ||

|

aquatic mammals | Marine mammalsform a diverse group of 128 species that rely on the ocean for their existence.[23]Whale meat is still harvested from legal, non-commercial hunts.[24]About one thousandlong-finned pilot whalesare still killed annually.[25]Japan has resumed hunting for whales, which they call "research whaling".[26]In modern Japan, two cuts of whale meat are usually distinguished: the belly meat and the more valued tail or fluke meat. Fluke meat can sell for $200 per kilogram, three times the price of belly meat.[27]Fin whalesare particularly desired because they are thought to yield the best quality fluke meat.[28]InTaijiin Japan and parts of Scandinavia such as theFaroe Islands,dolphinsare traditionally considered food, and are killed inharpoonordrive hunts.[29]Ringed sealsare still an important food source for the people ofNunavut[30]and are also hunted and eaten in Alaska.[31]The meat of sea mammals can be high in mercury, and may pose health dangers to humans when consumed.[32]The FAO record only the reported numbers of aquatic mammals harvested, and not the tonnage. In 2010, they reported 2500 whales, 12,000 dolphins and 182,000 seals.See:marine mammals as food,whale meat,seal hunting. | ? | |

|

aquatic reptiles | Sea turtleshave long been valued as food in many parts of the world. Fifth century BC Chinese texts describe sea turtles as exotic delicacies.[33]Sea turtles are caught worldwide, although in many countries it is illegal to hunt most species.[34]Many coastal communities around the world depend on sea turtles as a source of protein, often gathering sea turtle eggs, and keeping captured sea turtles alive on their backs until needed for consumption.[35]Most species of sea turtle are now endangered, and some arecritically endangered.[36] | 296+ | |

|

echinoderms | Echinodermsare headless invertebrates, found on theseafloorin all oceans and at all depths. They are not found in fresh water. They usually have a five-pointed radial symmetry, and move, breathe and perceive with their retractabletube feet.They are covered with a calcareous and spikytestor skin. The name echinoderm comes from the Greekekhinosmeaninghedgehog,anddermatosmeaningskin.Echinoderms used for seafood includesea cucumbers,sea urchins,and occasionallystarfish.Wild sea cucumbers are caught by divers and in China they are farmed commercially in artificial ponds.[37]Thegonadsof both male and female sea urchins, usually called sea urchinroeor corals,[38]are delicacies in many parts of the world.[39][40] | 373 | |

|

jellyfish | Jellyfishare soft and gelatinous, with a body shaped like an umbrella or bell which pulsates for locomotion. They have long, trailing tentacles with stings for capturing prey. They are found free-swimming in thewater columnin all oceans, and are occasionally found in freshwater. Jellyfish must be dried within hours to prevent spoiling. In Japan they are regarded as a delicacy. Traditional processing methods are carried out by a jellyfish master. This involve a 20 to 40-day multi-phase procedure which starts with removing the gonads andmucous membranes.The umbrella and oral arms are then treated with a mixture oftable saltandalum,and compressed. Processing reduces liquefaction, odor, the growth of spoilage organisms, and makes the jellyfish drier and more acidic, producing a crisp and crunchy texture. Onlyscyphozoanjellyfish belonging to the orderRhizostomeaeare harvested for food; about 12 of the approximately 85 species. Most of the harvest takes place in southeast Asia.[41][42][43] | 404

| |

|

other | Aquatic animals not included above, such aswaterfowl,frogs,spoon worms,peanut worms,palolo worms,lamp shells,lancelets,sea anemonesandsea squirts(pictured). | 336 | |

| aquatic plantsandmicrophytes | Total for aquatic plants and microphytes:

|

19,893 | ||

|

seaweed | Seaweed is a loose colloquial term which lacks a formal definition. Broadly, the term is applied to the larger,macroscopicforms ofalgae,as opposed tomicroalga.Examples of seaweed groups are the multicellularred,brownandgreen algae.[44]Edible seaweeds usually contain high amounts of fibre and, in contrast to terrestrial plants, contain acomplete protein.[45]Seaweeds are used extensively as food in coastal cuisines around the world. Seaweed has been a part of diets inChina,Japan,andKoreasince prehistoric times.[46]Seaweed is also consumed in many traditional European societies, inIcelandand westernNorway,the Atlantic coast ofFrance,northern and westernIreland,Walesand some coastal parts of South West England,[47]as well as Nova Scotia and Newfoundland.See:edible seaweed,seaweed farming,aquaculture of giant kelp,laverbread. | ||

|

microphytes | Microphytesare microscopic organisms, and can be algal, bacterial or fungal.Microalgaeare another type of aquatic plant, and includes species that can be consumed by humans and animals. Some species of aquatic bacteria can also be used as seafood, such asspirulina(pictured in tablet form),a type ofcyanobacteria.See:culture of microalgae in hatcheries. | ||

|

aquatic plants | Edible aquatic plants areflowering plantsandfernsthat have adapted to a life in water. Known examples areduck potato,water chestnut,cattail,watercress,lotusandnardoo. | ||

| Total production (thousand tonnes) | 168,447 | |||

Processing

[edit]Fish is a highlyperishableproduct: the "fishy" smell of dead fish is due to the breakdown ofamino acidsintobiogenic aminesandammonia.[48]

Livefood fishare often transported in tanks at high expense for aninternational marketthat prefers its seafood killed immediately before it is cooked. Delivery of live fish without water is also being explored.[49]While some seafoodrestaurantskeep live fish inaquariafor display purposes or cultural beliefs, the majority of live fish are kept for dining customers. The live food fish trade inHong Kong,for example, is estimated to have driven imports of live food fish to more than 15,000tonnesin 2000. Worldwide sales that year were estimated at US$400 million, according to the World Resources Institute.[50]

If thecool chainhas not been adhered to correctly, food products generally decay and become harmful before thevalidity dateprinted on the package. As the potential harm for a consumer when eating rotten fish is much larger than for example with dairy products, theU.S. Food and Drug Administration(FDA) has introduced regulation in the USA requiring the use of atime temperature indicatoron certain fresh chilled seafood products.[51]

Because fresh fish is highly perishable, it must be eaten promptly or discarded; it can be kept for only a short time. In many countries, fresh fish arefilletedand displayed for sale on a bed ofcrushed iceorrefrigerated.Fresh fish is most commonly found near bodies of water, but the advent of refrigeratedtrainandtrucktransportationhas made fresh fish more widely available inland.[52]

Long termpreservationof fish is accomplished in a variety of ways. The oldest and still most widely used techniques aredryingandsalting.Desiccation(complete drying) is commonly used to preserve fish such ascod.Partial drying and salting are popular for the preservation of fish likeherringandmackerel.Fish such assalmon,tuna,andherringare cooked andcanned.Most fish are filleted before canning, but some small fish (e.g.sardines) are onlydecapitatedand gutted before canning.[53]

Consumption

[edit]This sectionneeds additional citations forverification.(July 2021) |

Seafood is consumed all over the world; it provides the world's prime source of high-qualityprotein:14–16% of the animal protein consumed worldwide; over one billion people rely on seafood as their primary source of animal protein.[54][55]Fish is among the most commonfood allergens.

Since 1960, annual global seafood consumption has more than doubled to over 20 kg per capita. Among the top consumers are Korea (78.5 kg per head), Norway (66.6 kg) and Portugal (61.5 kg).[56]

The UKFood Standards Agencyrecommends that at least two portions of seafood should be consumed each week, one of which should be oil-rich. There are over 100 different types of seafood available around the coast of the UK.

Oil-rich fish such asmackerelorherringare rich in long chainOmega-3oils. These oils are found in every cell of the human body, and are required for human biological functions such as brain functionality.

Whitefish such as haddock and cod are very low in fat and calories which, combined with oily fish rich inOmega-3such asmackerel,sardines,freshtuna,salmonandtrout,can help to protect againstcoronary heart disease,as well as helping to develop strong bones and teeth.

Shellfishare particularly rich inzinc,which is essential for healthy skin and muscles as well as fertility.Casanovareputedly ate 50oystersa day.[57][58]

Texture and taste

[edit]Over 33,000speciesof fish and many more marine invertebrate species have been identified.[59]Bromophenols, which are produced by marine algae, give marine animals an odor and taste that is absent from freshwater fish and invertebrates. Also, a chemical substance called dimethylsulfoniopropionate (DMSP) that is found in red and green algae is transferred into animals in the marine food chain. When broken down, dimethyl sulfide (DMS) is produced, and is often released during food preparation when fresh fish and shellfish are heated. In small quantities it creates a specific smell one associates with the ocean, but in larger quantities gives the impression of rotten seaweed and old fish.[60]Another molecule known asTMAOoccurs in fishes and gives them a distinct smell. It also exists in freshwater species, but becomes more numerous in the cells of an animal the deeper it lives, so fish from the deeper parts of the ocean have a stronger taste than species that live in shallow water.[61]Eggs from seaweed contain sex pheromones called dictyopterenes, which are meant to attract the sperm. These pheromones are also found in edible seaweeds, which contributes to their aroma.[62]

Health benefits

[edit]

There is broad scientific consensus thatdocosahexaenoic acid (DHA)andeicosapentaenoic acid (EPA)found in seafood are beneficial toneurodevelopmentand cognition, especially at young ages.[64][65]The United NationsFood and Agriculture Organizationhas described fish as "nature's super food."[66]Seafood consumption is associated with improved neurologic development duringpregnancy[67][68]and early childhood[69]and is more tenuously linked to reduced mortality fromcoronary heart disease.[70]

Fish consumption has been associated with a decreased risk ofdementia,lung cancerandstroke.[71][72][73]A 2020umbrella reviewconcluded that fish consumption reduces all-cause mortality, cancer, cardiovascular disease, stroke and other outcomes. The review suggested that two to four servings per week is generally safe.[74]However, two other recent umbrella reviews have found no statistically significant associations between fish consumption and cancer risks and have cautioned researchers when it comes to interpreting reported associations between fish consumption and cancer risks because the quality of evidence is very low.[75][76]

The parts of fish containing essential fats and micronutrients, often cited as primary health benefits of eating seafood, are frequently discarded in thedeveloped world.[77]Micronutrientsincluding calcium, potassium, selenium, zinc, and iodine are found in their highest concentrations in the head, intestines, bones, and scales.[78]

Government recommendations promote moderate consumption of fish. TheUS Food and Drug Administrationrecommends moderate (4 oz for children and 8–12 oz for adults, weekly) consumption of fish as part of a healthy and balanced diet.[79]The UK National Health Servicegives similar advice, recommending at least 2 portions (about 10 oz) of fish weekly.[80]TheChinese National Health Commissionrecommends slightly more, advising 10–20 oz of fish weekly.[81]

Health hazards

[edit]

There are numerous factors to consider when evaluating health hazards in seafood. These concerns include marine toxins, microbes,foodborne illness,radionuclide contamination,and man-made pollutants.[77]Shellfishare among the more commonfood allergens.[82]Most of these dangers can be mitigated or avoided with accurate knowledge of when and where seafood is caught. However, consumers have limited access to relevant and actionable information in this regard and the seafood industry's systemic problems with mislabelling make decisions about what is safe even more fraught.[83]

Ciguatera fish poisoning(CFP) is an illness resulting from consuming toxins produced bydinoflagellateswhich bioaccumulate in the liver, roe, head, and intestines ofreef fish.[84]It is the most common disease associated with seafood consumption and poses the greatest risk to consumers.[77]The population of plankton that produces these toxins varies significantly over time and location, as seen inred tides.Evaluating the risk of ciguatera in any given fish requires specific knowledge of its origin and life history, information that is often inaccurate or unavailable.[85]While ciguatera is relatively widespread compared to other seafood-related health hazards (up to 50,000 people suffer from ciguatera every year), mortality is very low.[86]

Scombroid food poisoning,is also a seafood illness. It is typically caused by eating fish high in histamine from being stored or processed improperly.[87]

Fishandshellfishhave a natural tendency to concentrate inorganic and organic toxins and pollutants in their bodies, includingmethylmercury,a highly toxic organic compound of mercury, polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), and microplastics. Species of fish that are high on thefood chain,such asshark,swordfish,king mackerel,albacore tuna,andtilefishcontain higher concentrations of these bioaccumulates. This is because bioaccumulates are stored in the muscle tissues of fish, and when a predatory fish eats another fish, it assumes the entire body burden of bioaccumulates in the consumed fish. Thus species that are high on thefood chainamass body burdens of bioaccumulates that can be ten times higher than the species they consume. This process is calledbiomagnification.[88]

Man-made disasters can cause localized hazards in seafood which may spread widely via piscine food chains. The first occurrence of widespreadmercury poisoningin humans occurred this way in the 1950s inMinamata,Japan.Wastewater from a nearby chemical factory released methylmercury that accumulated in fish which were consumed by humans. Severe mercury poisoning is now known asMinamata disease.[89][77]The 2011Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant disasterand 1947 - 1991Marshall Islands nuclear bomb testingled to dangerous radionuclide contamination of local sea life which, in the latter case, remained as of 2008.[90][77]

A widely cited study inJAMAwhich synthesized government andMEDLINEreports, and meta-analyses to evaluate risks from methylmercury, dioxins, and polychlorinated biphenyls to cardiovascular health and links between fish consumption and neurologic outcomes concluded that:

"The benefits of modest fish consumption (1-2 servings/wk) outweigh the risks among adults and, excepting a few selected fish species, among women of childbearing age. Avoidance of modest fish consumption due to confusion regarding risks and benefits could result in thousands of excess CHD [congenital heart disease] deaths annually and suboptimal neurodevelopment in children."[70]

Mislabelling

[edit]

Due to the wide array of options in the seafood marketplace, seafood is far more susceptible to mislabeling than terrestrial food.[77]There are more than 1,700 species of seafood in the United States' consumer marketplace, 80 - 90% of which are imported and less than 1% of which are tested for fraud.[92]However, more recent research into seafood imports and consumption patterns among consumers in the United States suggests that 35%-38% of seafood products are of domestic origin.[94]consumption suggests Estimates of mislabelled seafood in the United States range from 33% in general up to 86% for particular species.[92]

Byzantinesupply chains,frequent bycatch, brand naming, species substitution, and inaccurate ecolabels all contribute to confusion for the consumer.[95]A 2013 study byOceanafound that one third of seafood sampled from the United States was incorrectly labeled.[92]Snapperandtunawere particularly susceptible to mislabelling, and seafood substitution was the most common type of fraud. Another type of mislabelling is short-weighting, where practices such as overglasing or soaking can misleadingly increase the apparent weight of the fish.[96]For supermarket shoppers, many seafood products are unrecognisablefillets.Without sophisticatedDNA testing,there is no foolproof method to identify a fish species without their head, skin, and fins. This creates easy opportunities to substitute cheap products for expensive ones, a form of economic fraud.[97]

Beyond financial concerns, significant health risks arise from hidden pollutants and marine toxins in an already fraught marketplace. Seafood fraud has led to widespreadkeriorrheadue to mislabeled escolar, mercury poisoning from products marketed as safe for pregnant women, and hospitalisation and neurological damage due to mislabeledpufferfish.[93]For example, a 2014 study published inPLOS Onefound that 15% ofMSCcertifiedPatagonian toothfishoriginated from uncertified and mercury polluted fisheries. These fishery-stock substitutions had 100% more mercury than their genuine counterparts, "vastly exceeding" limits in Canada, New Zealand, and Australia.[98]

Sustainability

[edit]Research into population trends of various species of seafood is pointing to a global collapse of seafood species by 2048. Such a collapse would occur due to pollution andoverfishing,threatening oceanic ecosystems, according to some researchers.[99]

A major international scientific study released in November 2006 in the journalSciencefound that about one-third of all fishing stocks worldwide have collapsed (with a collapse being defined as a decline to less than 10% of their maximum observed abundance), and that if current trends continue all fish stocks worldwide will collapse within fifty years.[100]In July 2009,Boris WormofDalhousie University,the author of the November 2006 study inScience,co-authored an update on the state of the world's fisheries with one of the original study's critics,Ray Hilbornof theUniversity of Washingtonat Seattle. The new study found that through good fisheries management techniques even depleted fish stocks can be revived and made commercially viable again.[101]An analysis published in August 2020 indicates that seafood could theoretically increase sustainably by 36–74% by 2050 compared to current yields and that whether or not these production potentials are realisedsustainablydependson several factors "such as policy reforms, technological innovation, and the extent of future shifts in demand".[102][103]

TheFAOState of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2004 report estimates that in 2003, of the main fish stocks or groups of resources for which assessment information is available, "approximately one-quarter wereoverexploited,depleted or recovering from depletion (16%, 7% and 1% respectively) and needed rebuilding. "[104]

TheNational Fisheries Institute,a trade advocacy group representing the United States seafood industry, disagree. They claim that currently observed declines in fish populations are due to natural fluctuations and that enhanced technologies will eventually alleviate whatever impact humanity is having on oceanic life.[105]

In religion

[edit]For the most partIslamic dietary lawsallow the eating of seafood, though theHanbaliforbid eels, theShafiforbid frogs and crocodiles, and theHanafiforbidbottom feederssuch as shellfish andcarp.[106]TheJewishlaws ofKashrutforbid the eating of shellfish and eels.[107]In the Old Testament, theMosaic Covenantallowed the Israelites to eatFinfish,but shellfish and eels werean abominationand not allowed.[108]

In theNew Testament,Luke's gospelreports Jesus' eating of a fish after hisresurrection,[109]and inJohn 21,also a post-resurrection scene, Jesus tells hisdiscipleswhere they can catch fish, before cooking breakfast for them to eat.[110]

Pescatarianismwas widespread in theearly Christian Church,among both the clergy and laity.[111]In ancient and medieval times, theCatholic Churchforbade the practice of eating meat, eggs and dairy products duringLent.Thomas Aquinasargued that these "afford greater pleasure as food [than fish], and greater nourishment to the human body, so that from their consumption there results in a greater surplus available for seminal matter, which when abundant becomes a great incentive to lust".[112]In the United States, the Catholic practice ofabstaining from meaton Fridays duringLenthas popularised the Fridayfish fry,[113]and parishes often sponsor afish fryduring Lent.[114]In predominantly Roman Catholic areas, restaurants may adjust their menus during Lent by adding seafood items to the menu.[115]

See also

[edit]- Cold chain

- Culinary name

- Fish as food

- Fish processing

- Fish market

- Friend of the Sea

- Got Mercury?

- Jellyfish as food

- List of fish dishes

- List of foods

- List of harvested aquatic animals by weight

- List of seafood companies

- List of seafood dishes

- List of seafood restaurants

- Oyster bar

- Raw bar

- Safe Harbor Certified Seafood

- Seafood Watch,sustainable consumer guide (USA)

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^Fish and seafood consumptionOur World in Data

- ^abInman, Mason (17 October 2007)."African Cave Yields Earliest Proof of Beach Living".National Geographic News. Archived fromthe originalon 18 October 2007.

- ^African Bone Tools Dispute Key Idea About Human EvolutionNational Geographic News article.

- ^"Neanderthals ate shellfish 150,000 years ago: study".Phys.org. 15 September 2011.

- ^Yaowu Hu, Y; Hong Shang, H; Haowen Tong, H; Olaf Nehlich, O; Wu Liu, W; Zhao, C; Yu, J; Wang, C; Trinkaus, E; Richards, M (2009)."Stable isotope dietary analysis of the Tianyuan 1 early modern human".Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.106(27): 10971–10974.Bibcode:2009PNAS..10610971H.doi:10.1073/pnas.0904826106.PMC2706269.PMID19581579.

- ^First direct evidence of substantial fish consumption by early modern humans in ChinaPhysOrg.com,6 July 2009.

- ^Coastal Shell Middens and Agricultural Origins in Atlantic Europe.

- ^"Fisheries history: Gift of the Nile"(PDF).Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 10 November 2006.

- ^abBased on data extracted from the FAOFishStat database22 July 2012.

- ^Dalby, p.67.

- ^Image of fishing illustrated in a Roman mosaicArchived17 July 2011 at theWayback Machine.

- ^Adamson (2002), p. 11.

- ^Adamson (2004), pp. 45–39.

- ^"ASFIS List of Species for Fishery Statistics Purposes".Fishery Fact Sheets.Food and Agriculture Organization.Retrieved22 July2012.

- ^abTotal production, both wild and aquaculture, of seafood species groups in thousand tonnes, sourced from the data reported in theFAOFishStat database

- ^Walrond CCarl. "Coastal fish – Fish of the open sea floor"Te Ara – the Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Updated 2 March 2009

- ^"Definition of calamari".Merriam-Webster'sOnline Dictionary.18 August 2023.

- ^* Rudloe, Jack and Rudloe, Anne (2009)Shrimp: The Endless Quest for Pink GoldFT Press.ISBN9780137009725.

- ^Includes crabs, sea spiders, king crabs and squat lobsters

- ^Includes lobsters, spiny-rock lobsters

- ^abSteven Nicol & Yoshinari Endo (1997).Krill Fisheries of the World.Fisheries Technical Paper. Vol. 367.Food and Agriculture Organization.ISBN978-92-5-104012-6.

- ^"Brine Shrimp Artemia as a Direct Human Food"(PDF).Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 30 January 2022.Retrieved30 January2022.

- ^Pompa, S.; Ehrlich, P. R.; Ceballos, G. (2011)."Global distribution and conservation of marine mammals".PNAS.108(33): 13600–13605.Bibcode:2011PNAS..10813600P.doi:10.1073/pnas.1101525108.PMC3158205.PMID21808012.

- ^"Native Alaskans say oil drilling threatens way of life".BBC News.20 July 2010.Retrieved11 August2010.

- ^Nguyen, Vi (26 November 2010)."Warning over contaminated whale meat as Faroe Islands' killing continues".The Ecologist.

- ^"Greenpeace: Stores, eateries less inclined to offer whale".The Japan Times Online.8 March 2008.Retrieved29 July2010.

- ^Palmer, Brian (11 March 2010)."What Does Whale Taste Like?".Slate Magazine.Retrieved29 July2010.

- ^Kershaw 1988,p.67

- ^ Matsutani, Minoru (23 September 2009)."Details on how Japan's dolphin catches work".Japan Times.p. 3.

- ^"Eskimo Art, Inuit Art, Canadian Native Artwork, Canadian Aboriginal Artwork".Inuitarteskimoart.com. Archived fromthe originalon 30 May 2013.Retrieved7 May2009.

- ^"Seal Hunt Facts".Sea Shepherd. Archived fromthe originalon 11 October 2008.Retrieved24 July2011.

- ^ Johnston, Eric (23 September 2009)."Mercury danger in dolphin meat".Japan Times.p. 3.

- ^Schafer, Edward H.(1962). "Eating Turtles in Ancient China".Journal of the American Oriental Society.82(1): 73–74.doi:10.2307/595986.JSTOR595986.

- ^CITES(14 June 2006)."Appendices".Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Flora and Fauna. Archived fromthe original(SHTML)on 3 February 2007.Retrieved5 February2007.

- ^Settle, Sam (1995)."Status of Nesting Populations of Sea Turtles in Thailand and Their Conservation".Marine Turtle Newsletter.68:8–13.

- ^International Union for the Conservation of Nature."IUCN Red List of Endangered Species".Retrieved12 April2012.

- ^Ess, Charlie."Wild product's versatility could push price beyond $2 for Alaska dive fleet".National Fisherman. Archived fromthe originalon 22 January 2009.Retrieved1 August2008.

- ^Rogers-Bennett, Laura, "The Ecology ofStrongylocentrotus franciscanusandStrongylocentrotus purpuratus"inJohn M. Lawrence,Edible sea urchins: biology and ecology,p. 410

- ^Alan Davidson,Oxford Companion to Food,s.v.sea urchin

- ^Lawrence, John M., "Sea Urchin Roe Cuisine"inJohn M. Lawrence,Edible sea urchins: biology and ecology

- ^Omori M, Nakano E (2001). "Jellyfish fisheries in southeast Asia".Hydrobiologia.451:19–26.doi:10.1023/A:1011879821323.S2CID6518460.

- ^Hsieh, Yun-Hwa P; Leong, F-M; Rudloe, J (2001). "Jellyfish as food".Hydrobiologia.451(1–3): 11–17.doi:10.1023/A:1011875720415.S2CID20719121.

- ^Li, Jian-rong; Hsieh, Yun-Hwa P (2004)."Traditional Chinese food technology and cuisine"(PDF).Asia Pacific J Clin Nutr.13(2): 147–155.PMID15228981.

- ^Smith, G.M. 1944.Marine Algae of the Monterey Peninsula, California.Stanford Univ., 2nd Edition.

- ^K.H. Wong; Peter C.K. Cheung (2000). "Nutritional evaluation of some subtropical red and green seaweeds: Part I – proximate composition, amino acid profiles and some physico-chemical properties".Food Chemistry.71(4): 475–482.doi:10.1016/S0308-8146(00)00175-8.

- ^"Seaweed as Human Food".Michael Guiry's Seaweed Site. Archived fromthe originalon 8 October 2011.Retrieved11 November2011.

- ^"Spotlight presenters in a lather over laver".BBC. 25 May 2005.Retrieved11 November2011.

- ^N. Narain and Nunes, M.L. Marine Animal and Plant Products.In:Handbook of Meat, Poultry and Seafood Quality, L.M.L. Nollet and T. Boylston, eds. Blackwell Publishing 2007, p 247.

- ^"WIPO".Archived fromthe originalon 15 October 2008.Retrieved1 May2009.

- ^The World Resources Institute, The live reef fish tradeArchived7 February 2007 at theWayback Machine

- ^"La Rosa Logistics Inc 14-Jan-03".Fda.gov.Retrieved2 April2012.

- ^Hicks, Doris T. (28 October 2016)."Seafood Safety and Quality: The Consumer's Role".Foods.5(4): 71.doi:10.3390/foods5040071.ISSN2304-8158.PMC5302431.PMID28231165.

- ^Messina, Concetta Maria; Arena, Rosaria; Ficano, Giovanna; Randazzo, Mariano; Morghese, Maria; La Barbera, Laura; Sadok, Saloua; Santulli, Andrea (21 October 2021)."Effect of Cold Smoking and Natural Antioxidants on Quality Traits, Safety and Shelf Life of Farmed Meagre (Argyrosomus regius) Fillets, as a Strategy to Diversify Aquaculture Products".Foods.10(11): 2522.doi:10.3390/foods10112522.ISSN2304-8158.PMC8619432.PMID34828803.

- ^World Health Organization[1].

- ^Tidwell, James H.; Allan, Geoff L. (2001)."Fish as food: aquaculture's contribution Ecological and economic impacts and contributions of fish farming and capture fisheries".EMBO Reports.2(11): 958–963.doi:10.1093/embo-reports/kve236.PMC1084135.PMID11713181.

- ^How much fish do we consume? First global seafood consumption footprint publishedEuropean Commission science and knowledge service.Last update: 27/ September 2018.

- ^Slovenko R (2001)"Aphrodisiacs-Then and Now"Journal of Psychiatry and Law,29:103f.

- ^Patrick McMurray (2007).Consider the Oyster: A Shucker's Field Guide.St. Martin's Press. p. 15.ISBN978-0-312-37736-6.

- ^FishBase:October 2017 update.Retrieved 30 December 2017.

- ^"The Science of Seaweeds | American Scientist".6 February 2017.

- ^"BBC – Earth – What does it take to live at the bottom of the ocean?".

- ^"Why Does The Sea Smell Like The Sea? | Popular Science".19 August 2014.

- ^Peterson, James and editors of Seafood Business (2009)Seafood Handbook: The Comprehensive Guide to Sourcing, Buying and PreparationJohn Wiley & Sons.ISBN9780470404164.

- ^Harris, W S; Baack, M L (30 October 2014)."Beyond building better brains: bridging the docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) gap of prematurity".Journal of Perinatology.35(1): 1–7.doi:10.1038/jp.2014.195.ISSN0743-8346.PMC4281288.PMID25357095.

- ^Hüppi, Petra S (1 March 2008)."Nutrition for the Brain: Commentary on the article by Isaacs et al. on page 308".Pediatric Research.63(3): 229–231.doi:10.1203/pdr.0b013e318168c6d1.ISSN0031-3998.PMID18287959.S2CID6564743.

- ^Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. 2016b. The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture: Contributing to Food Security and Nutrition for AIL Rome: FAO.

- ^Hibbeln, Joseph R; Davis, John M; Steer, Colin; Emmett, Pauline; Rogers, Imogen; Williams, Cathy; Golding, Jean (February 2007). "Maternal seafood consumption in pregnancy and neurodevelopmental outcomes in childhood (ALSPAC study): an observational cohort study".The Lancet.369(9561): 578–585.doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(07)60277-3.ISSN0140-6736.PMID17307104.S2CID35798591.

- ^Fewtrell, Mary S; Abbott, Rebecca A; Kennedy, Kathy; Singhal, Atul; Morley, Ruth; Caine, Eleanor; Jamieson, Cherry; Cockburn, Forrester; Lucas, Alan (April 2004). "Randomized, double-blind trial of long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acid supplementation with fish oil and borage oil in preterm infants".The Journal of Pediatrics.144(4): 471–479.doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2004.01.034.ISSN0022-3476.PMID15069395.

- ^Daniels, Julie L.; Longnecker, Matthew P.; Rowland, Andrew S.; Golding, Jean (July 2004)."Fish Intake During Pregnancy and Early Cognitive Development of Offspring".Epidemiology.15(4): 394–402.doi:10.1097/01.ede.0000129514.46451.ce.ISSN1044-3983.PMID15232398.S2CID22517733.

- ^abMozaffarian, Dariush; Rimm, Eric B. (18 October 2006)."Fish Intake, Contaminants, and Human Health".JAMA.296(15): 1885–99.doi:10.1001/jama.296.15.1885.ISSN0098-7484.PMID17047219.

- ^Song, Jian; Hong, Su; Wang, Bao-long; Zhou, Yang-yang; Guo, Liang-Liang (2014)."Fish Consumption and Lung Cancer Risk: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis".Nutrition and Cancer.66(44): 539–549.doi:10.1080/01635581.2014.894102.PMID24707954.S2CID38143108.

{{cite journal}}:CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^Bakre AT, Chen R, Khutan R, Wei L, Smith T, Qin G, Danat IM, Zhou W, Schofield P, Clifford A, Wang J, Verma A, Zhang C, Ni J (2018)."Association between fish consumption and risk of dementia: a new study from China and a systematic literature review and meta-analysis".Public Health Nutrition.21(10): 1921–1932.doi:10.1017/S136898001800037X.PMC10260768.PMID29551101.S2CID3983960.

{{cite journal}}:CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^Zhao, Wei; Tang, Hui; Xiaodong, Yang; Xiaoquan, Luo; Wang, Xiaoya; Shao, Chuan; He, Jiaquan (2019)."Fish Consumption and Stroke Risk: A Meta-Analysis of Prospective Cohort Studies".Journal of Stroke & Cerebrovascular Diseases.28(3): 604–611.doi:10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2018.10.036.PMID30470619.S2CID53719088.

{{cite journal}}:CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^Li, Ni; Wu, Xiaoting; Zhuang, Wen; Xia, Lin; Chen, Yi; Wu, Chuncheng; Rao, Zhiyong; Du, Liang; Zhao, Rui; Yi, Mengshi; Wan, Qianyi; Zhou, Yong (2020)."Fish consumption and multiple health outcomes: Umbrella review".Trends in Food Science and Technology.99:273–283.doi:10.1016/j.tifs.2020.02.033.S2CID216445490.

{{cite journal}}:CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^Jayedi, Ahmad; Shab-Bidar, Sakineh (2020)."Fish Consumption and the Risk of Chronic Disease: An Umbrella Review of Meta-Analyses of Prospective Cohort Studies".Advances in Nutrition.11(5): 1123–1133.doi:10.1093/advances/nmaa029.PMC7490170.PMID32207773.

{{cite journal}}:CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^Keum Hwa Lee, Hyo Jin Seong, Gaeun Kim, Gwang Hun Jeong, Jong Yeob Kim, Hyunbong Park, Eunyoung Jung, Andreas Kronbichler, Michael Eisenhut, Brendon Stubbs, Marco Solmi, Ai Koyanagi, Sung Hwi Hong, Elena Dragioti, Leandro Fórnias Machado de Rezende, Louis Jacob, NaNa Keum, Hans J van der Vliet, Eunyoung Cho, Nicola Veronese, Giuseppe Grosso, Shuji Ogino, Mingyang Song, Joaquim Radua, Sun Jae Jung, Trevor Thompson, Sarah E Jackson, Lee Smith, Lin Yang, Hans Oh, Eun Kyoung Choi, Jae Il Shin, Edward L Giovannucci, Gabriele Gamerith (2020)."Consumption of Fish and ω-3 Fatty Acids and Cancer Risk: An Umbrella Review of Meta-Analyses of Observational Studies".Advances in Nutrition.11(5): 1134–1149.doi:10.1093/advances/nmaa055.PMC7490175.PMID32488249.

{{cite journal}}:CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^abcdefHamada, Shingo; Wilk, Richard (2019).Seafood: Ocean to the Plate.New York: Routledge. pp. 2, 8, 5–7, 9, 5, 9, 115 (in order of parenthetical appearance).ISBN9781138191860.

- ^"Report of the Joint FAO/WHO Expert Consultation on the Risks and Benefits of Fish Consumption"(PDF).FAO Fisheries and Aquaculture Report.978:25–29. January 2010.eISSN2070-6987.

- ^"Advice About Eating Fish"(PDF).United States Environmental Protection Agency.July 2019.Retrieved8 May2020.

- ^"Fish and shellfish".nhs.uk.27 April 2018.Retrieved9 May2020.

- ^"《 trung quốc cư dân thiện thực chỉ nam ( 2016 ) 》 hạch tâm thôi tiến _ trung quốc cư dân thiện thực chỉ nam".dg.cnsoc.org.Retrieved9 May2020.

- ^"Common Food Allergens".Food Allergy & Anaphylaxis Network.Archived fromthe originalon 13 June 2007.Retrieved24 June2007.

- ^Landrigan, Philip J.; Raps, Hervé; Cropper, Maureen; Bald, Caroline; Brunner, Manuel; Canonizado, Elvia Maya; Charles, Dominic; Chiles, Thomas C.; Donohue, Mary J.; Enck, Judith; Fenichel, Patrick; Fleming, Lora E.; Ferrier-Pages, Christine; Fordham, Richard; Gozt, Aleksandra (2023)."The Minderoo-Monaco Commission on Plastics and Human Health".Annals of Global Health.89(1): 23.doi:10.5334/aogh.4056.ISSN2214-9996.PMC10038118.PMID36969097.

- ^Ansdell, Vernon (2019), "Seafood Poisoning",Travel Medicine,Elsevier, pp. 449–456,doi:10.1016/b978-0-323-54696-6.00049-5,ISBN978-0-323-54696-6

- ^Brand, Larry E.; Campbell, Lisa; Bresnan, Eileen (February 2012)."Karenia: The biology and ecology of a toxic genus".Harmful Algae.14:156–178.doi:10.1016/j.hal.2011.10.020.ISSN1568-9883.PMC9891709.PMID36733478.

- ^"Ciguatera Fish Poisoning—New York City, 2010-2011".JAMA.309(11): 1102. 20 March 2013.doi:10.1001/jama.2013.1523.ISSN0098-7484.

- ^"Scombroid Fish Poisoning".California Department of Public Health.Retrieved22 March2024.

- ^Smith, Madeleine; Love, David C.; Rochman, Chelsea M.; Neff, Roni A. (2018)."Microplastics in Seafood and the Implications for Human Health".Current Environmental Health Reports.5(3): 375–386.doi:10.1007/s40572-018-0206-z.ISSN2196-5412.PMC6132564.PMID30116998.

- ^Osiander, A. (1 October 2002). "Minamata: Pollution and the Struggle for Democracy in Postwar Japan, by Timothy S. George. Cambridge, MA and London: Harvard University Press, 2001, xxi + 385 pp., $45.00 (hardcover ISBN 0-674-00364-0), $25.00 (paperback ISBN 0-674-00785-9)".Social Science Japan Journal.5(2): 273–275.doi:10.1093/ssjj/05.2.273.ISSN1369-1465.

- ^Johnston, Barbara Rose; Barker, Holly M. (26 March 2020).Consequential Damages of Nuclear War.doi:10.1201/9781315431819.ISBN9781315431819.S2CID241941148.

- ^Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition (U.S.).The bad bug book: foodborne pathogenic microorganisms and natural toxins handbook(PDF).U.S. Food & Drug Administration, Center for Food Safety & Applied Nutrition. p. 237.LCCN2004616584.OCLC49526684.

- ^abcdKimberly Warner; Walker Timme; Beth Lowell; Michael Hirschfield (2013).Oceana study reveals seafood fraud nationwide.Oceana.OCLC828208760.

{{cite book}}:CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^abWillette, Demian A.; Simmonds, Sara E.; Cheng, Samantha H.; Esteves, Sofia; Kane, Tonya L.; Nuetzel, Hayley; Pilaud, Nicholas; Rachmawati, Rita; Barber, Paul H. (10 May 2017). "Using DNA barcoding to track seafood mislabeling in Los Angeles restaurants".Conservation Biology.31(5): 1076–1085.doi:10.1111/cobi.12888.ISSN0888-8892.PMID28075039.S2CID3788104.

- ^Gephart, Jessica A.; Froehlich, Halley E.; Branch, Trevor A. (2019)."Opinion: To create sustainable seafood industries, the United States needs a better accounting of imports and exports".Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.116(19): 9142–9146.doi:10.1073/pnas.1905650116.PMC6511020.PMID31068476.

- ^Jacquet, Jennifer L.; Pauly, Daniel (May 2008). "Trade secrets: Renaming and mislabeling of seafood".Marine Policy.32(3): 309–318.CiteSeerX10.1.1.182.1143.doi:10.1016/j.marpol.2007.06.007.ISSN0308-597X.

- ^"FishWatch – Fraud".Retrieved21 December2018.

- ^Nutrition, Center for Food Safety and Applied (3 November 2018)."Seafood Species Substitution and Economic Fraud".FDA.

- ^Marko, Peter B.; Nance, Holly A.; van den Hurk, Peter (5 August 2014)."Seafood Substitutions Obscure Patterns of Mercury Contamination in Patagonian Toothfish (Dissostichus eleginoides) or" Chilean Sea Bass "".PLOS ONE.9(8): e104140.Bibcode:2014PLoSO...9j4140M.doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0104140.ISSN1932-6203.PMC4122487.PMID25093736.

- ^World Seafood Supply Could Run Out by 2048 Researchers Warnboston.com. Retrieved 6 February 2007

- ^"'Only 50 years left' for sea fish",BBC News. 2 November 2006.

- ^Study Finds Hope in Saving Saltwater FishThe New York Times.Retrieved 4 August 2009

- ^"Food from the sea: Sustainably managed fisheries and the future".phys.org.Retrieved6 September2020.

- ^Costello, Christopher; Cao, Ling; Gelcich, Stefan; Cisneros-Mata, Miguel Á; Free, Christopher M.; Froehlich, Halley E.; Golden, Christopher D.; Ishimura, Gakushi; Maier, Jason; Macadam-Somer, Ilan; Mangin, Tracey; Melnychuk, Michael C.; Miyahara, Masanori; de Moor, Carryn L.; Naylor, Rosamond; Nøstbakken, Linda; Ojea, Elena; O’Reilly, Erin; Parma, Ana M.; Plantinga, Andrew J.; Thilsted, Shakuntala H.; Lubchenco, Jane (19 August 2020)."The future of food from the sea".Nature.588(7836): 95–100.Bibcode:2020Natur.588...95C.doi:10.1038/s41586-020-2616-y.hdl:11093/1616.ISSN1476-4687.PMID32814903.S2CID221179212.

- ^"The Status of the Fishing Fleet".The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture: 2004.Food and Agriculture Organization.Archivedfrom the original on 19 January 2018.Retrieved22 May2020.

- ^Seafood Could Collapse by 2050, Experts Warn,NBC News. Retrieved 22 July 2007.

- ^Is seafood Haram or Halal?Questions on Islam.Updated 23 December 2008. Retrieved 6 January 2013.

- ^Yoreh De'ah – Shulchan-AruchArchived3 June 2012 at theWayback MachineChapter 1,torah.org.Retrieved 17 June 2012.

- ^"All that are in the waters: all that... hath not fins and scales ye may not eat" (Deuteronomy 14:9–10) and are "an abomination" (Leviticus 11:9–12).

- ^Luke 24:42

- ^John 21:1–14

- ^Walters, Kerry S.; Portmess, Lisa (31 May 2001).Religious Vegetarianism: From Hesiod to the Dalai Lama.SUNY Press. p. 124.ISBN9780791490679.

- ^"Summa Theologica, Q147a8".Newadvent.org.Retrieved27 August2010.

- ^Walkup, Carolyn (8 December 2003)."You can take the girl out of Wisconsin, but the lure of its food remains".Nation's Restaurant News.Archived fromthe originalon 11 July 2012.Retrieved25 February2009.

- ^Connie Mabin (2 March 2007)."For Lent, Parishes Lighten Up Fish Fry".Washington Post.Retrieved25 February2009.

- ^Carlino, Bill (19 February 1990)."Seafood promos aimed to 'lure' Lenten observers".Nation's Restaurant News.Archived fromthe originalon 9 July 2012.Retrieved25 February2009.

Sources

[edit]- Adamson, Melitta Weiss (2004)Food in Medieval TimesGreenwood Press.ISBN0-313-32147-7.

- Adamson, Melitta Weiss (2002)Regional Cuisines of Medieval Europe: A Book of EssaysRoutledge.ISBN9780415929943.

- Alasalvar C, Miyashita K, Shahidi F and Wanasundara U (2011)Handbook of Seafood Quality, Safety and Health ApplicationsJohn Wiley & Sons.ISBN9781444347760.

- Athenaeusof NaucratisThe Deipnosophists; or, Banquet of the learnedVol 3, Charles Duke Yonge (trans) 1854. H.G. Bohn.

- Dalby, A.(1996)Siren Feasts: A History of Food and Gastronomy in GreeceRoutledge.ISBN0-415-15657-2.

- Granata LA, Flick GJ Jr and Martin RE (eds) (2012)The Seafood Industry: Species, Products, Processing, and SafetyJohn Wiley & Sons.ISBN9781118229538.

- Green, Aliza (2007)Field Guide to Seafood: How to Identify, Select, and Prepare Virtually Every Fish and Shellfish at the MarketQuirk Books.ISBN9781594741357.

- McGee, Harold (2004)On Food And Cooking: The Science and Lore of the KitchenSimon and Schuster.ISBN9780684800011.

- Peterson, James and editors of Seafood Business (2009)Seafood Handbook: The Comprehensive Guide to Sourcing, Buying and PreparationJohn Wiley & Sons.ISBN9780470404164.

- Potter, Jeff (2010)Cooking for Geeks: Real Science, Great Hacks, and Good FoodO'Reilly Media.ISBN9780596805883.

- Silverstein, Alvin; Silverstein, Virginia B. & Silverstein, Robert A. (1995).The Sea Otter.Brookfield, Connecticut: The Millbrook Press, Inc.ISBN978-1-56294-418-6.OCLC30436543.

- Regensteinn J M and Regensteinn C E (2000)"Religious food laws and the seafood industry"In: R E Martin, E P Carter, G J Flick Jr and L M Davis (Eds) (2000)Marine and freshwater products handbook,CRC Press.ISBN9781566768894.

- Snodgrass, Mary Ellen(2004)Encyclopedia of Kitchen HistoryISBN9781579583804.

- Stickney, Robert (2009)Aquaculture: An Introductory TextCABI.ISBN9781845935894.

- Tidwell, James H.; Allan, Geoff L. (2001)."Fish as food: aquaculture's contribution Ecological and economic impacts and contributions of fish farming and capture fisheries".EMBO Reports.2(11): 958–963.doi:10.1093/embo-reports/kve236.PMC1084135.PMID11713181.

Further reading

[edit]- Alasalvar C, Miyashita K, Shahidi F and Wanasundara U (2011)Handbook of Seafood Quality, Safety and Health Applications,John Wiley & Sons.ISBN9781444347760.

- Ainsworth, Mark (2009)Fish and Seafood: Identification, Fabrication, UtilizationCengage Learning.ISBN9781435400368.

- Anderson, James L (2003)The International Seafood TradeWoodhead Publishing.ISBN9781855734562.

- Babal, Ken (2010)Seafood Sense: The Truth about Seafood Nutrition and SafetyReadHowYouWant.com.ISBN9781458755995.

- Botana, Luis M (2000)Seafood and Freshwater Toxins: Pharmacology, Physiology and DetectionCRC Press.ISBN9780824746339.

- Boudreaux, Edmond (2011)The Seafood Capital of the World: Biloxi's Maritime HistoryThe History Press.ISBN9781609492847.

- Granata LA, Martin RE and Flick GJ Jr (2012)The Seafood Industry: Species, Products, Processing, and SafetyJohn Wiley & Sons.ISBN9781118229538.

- Greenberg, Paul (2015).American Catch: The Fight for Our Local Seafood.Penguin Books.ISBN978-0143127437.

- Luten, Joop B (Ed.) (2006)Seafood Research From Fish To Dish: Quality, Safety and Processing of Wild and Farmed FishWageningen Academic Pub.ISBN9789086860050.

- McDermott, Ryan (2007)Toward a More Efficient Seafood Consumption AdvisoryProQuest.ISBN9780549183822.

- Nesheim MC and Yaktine AL (Eds) (2007)Seafood Choices: Balancing Benefits and RisksNational Academies Press.ISBN9780309102186.

- Shames, Lisa (2011)Seafood Safety: FDA Needs to Improve Oversight of Imported Seafood and Better Leverage Limited ResourcesDIANE Publishing.ISBN9781437985948.

- Robson, A. (2006)."Shellfish view of omega-3 and sustainable fisheries".Nature.444(7122): 1002.Bibcode:2006Natur.444.1002R.doi:10.1038/4441002d.

- Trewin C and Woolfitt A (2006)Cornish Fishing and SeafoodAlison Hodge Publishers.ISBN9780906720424.

- UNEP(2009)The Role of Supply Chains in Addressing the Global Seafood CrisisUNEP/Earthprint

- Upton, Harold F (2011)Seafood Safety: Background IssuesDIANE Publishing.ISBN9781437943832.