Shapur I

You can helpexpand this article with text translated fromthe corresponding articlein Portuguese.(January 2019)Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

This articleneeds additional citations forverification.(April 2018) |

| Shapur I 𐭱𐭧𐭯𐭥𐭧𐭥𐭩 | |

|---|---|

Reconstruction of theColossal Statue of Shapur IbyGeorge Rawlinson,1876 | |

| King of Kings of Iran and non-Iran[a] | |

| Reign | 12 April 240 – May 270 |

| Predecessor | Ardashir I |

| Successor | Hormizd I |

| Died | May 270 Bishapur |

| Consort | Khwarranzem al-Nadirah(?) |

| Issue | Bahram I Shapur Mishanshah Hormizd I Narseh Shapurdukhtak(?) Adur-Anahid |

| House | House of Sasan |

| Father | Ardashir I |

| Mother | MurrodorDenag |

| Religion | Zoroastrianism |

Shapur I(also spelledShabuhr I;Middle Persian:𐭱𐭧𐭯𐭥𐭧𐭥𐭩,romanized:Šābuhr) was the secondSasanianKing of KingsofIran.The precise dating of his reign is disputed, but it is generally agreed that he ruled from 240 to 270, with his fatherArdashir Ias co-regent until the death of the latter in 242. During his co-regency, he helped his father with the conquest and destruction of the city ofHatra,whose fall was facilitated, according to Islamic tradition, by the actions of his future wifeal-Nadirah.Shapur also consolidated and expanded the empire of Ardashir I, waged war against theRoman Empire,and seized its cities ofNisibisandCarrhaewhile he was advancing as far asRoman Syria.Although he was defeated at theBattle of Resaenain 243 by Roman emperorGordian III(r. 238–244), he was the following year able to win theBattle of Misicheand force the new Roman emperorPhilip the Arab(r. 244–249) to sign a favorable peace treaty that was regarded by the Romans as "a most shameful treaty".[1]

Shapur later took advantage of the political turmoil within the Roman Empire by undertaking a second expedition against it in 252/3–256, sacking the cities ofAntiochandDura-Europos.In 260, during his third campaign, he defeated and captured the Roman emperor,Valerian.He did not seem interested in permanently occupying the Roman provinces, choosing instead to resort to plundering and pillaging, gaining vast amounts of riches. The captives of Antioch, for example, were allocated to the newly reconstructed city ofGundeshapur,later famous as a center of scholarship. In the 260s, subordinates of Shapur suffered setbacks againstOdaenathus,the king ofPalmyra.According to Shapur's inscription at Hajiabad, he still remained active at the court in his later years, participating inarchery.He died of illness inBishapur,most likely in May 270.[2]

Shapur was the first Iranian monarch to use the title of "King of Kings of Iranians and non-Iranians"; beforehand the royal titulary had been "King of Kings of Iranians". He had adopted the title due to the influx of Roman citizens whom he had deported during his campaigns. However, it was first under his son and successorHormizd I,that the title became regularised. Shapur had newZoroastrianfire templesconstructed, incorporated new elements into the faith from Greek and Indian sources, and conducted an extensive program of rebuilding and refounding of cities.

Etymology

[edit]"Shapur" was a popular name inSasanian Iran,being used by three Sasanian monarchs and other notables of the Sasanian era and its later periods. Derived fromOld Iranian*xšayaθiya.puθra( "son of a king" ), it must initially have been a title, which became—at least in the late 2nd century CE—a personal name.[1]It appears in the list ofArsacidkings in some Arabic-Persian sources; however, this isanachronistic.[1]Shapur is transliterated in other languages as;GreekSapur,SabourandSapuris;LatinSaporesandSapor;ArabicSāburandŠābur;New PersianŠāpur,Šāhpur,Šahfur.[1]

Background

[edit]According to the semi-legendaryKar-Namag i Ardashir i Pabagan,aMiddle Persianbiography ofArdashir I,[3]the daughter of the Parthian kingArtabanus IV,Zijanak, attempted to poison her husband Ardashir. Discovering her intentions, Ardashir ordered her to be executed. Finding out about her pregnancy, themobads(priests) were against it. Nevertheless, Ardashir still demanded her execution, which led themobadsto conceal her and her son Shapur for seven years, until the latter was identified by Ardashir, who chooses to adopt him based on his virtuous traits.[4]This type of narrative is repeated in Iranian historiography. According to 5th-century BCE Greek historianHerodotus,the Median kingAstyageswanted to have his grandsonCyruskilled because he believed that he would one day overthrow him. A similar narrative is also found in the story of the mythological Iranian kingKay Khosrow.[4]According to the modern historian Bonner, the story of Shapur's birth and uprising "may conceal a marriage between Ardashir and an Arsacid princess or perhaps merely a noble lady connected with the Parthian aristocracy."[5]On his inscriptions, Shapur identifies his mother as a certainMurrod.[5]

Background and state of Iran

[edit]Shapur I was a son of Ardashir I and his wifeMurrod[6][7][8]orDenag.[9]The background of the family is obscure; although based inPars(also known asPersis), they were not native to the area, and were seemingly originally from the east.[10][11]The historian Marek Jan Olbrycht has suggested that the family was descended from theIndo-ParthiansofSakastan.[10]IranologistKhodadad Rezakhani also noted similarities between the early Sasanians and the Indo-Parthians, such as their coinage.[12]Yet, he stated that "evidence might still be too inconclusive."[12]

Pars, a region in the southwesternIranian plateau,was the homeland of the southwestern branch of theIranian peoples,the Persians.[13]It was also the birthplace of the first Iranian Empire, theAchaemenids.[13]The region served as the centre of the empire until its conquest by theMacedoniankingAlexander the Great(r. 336–323 BCE).[13]Since the end of the 3rd or the beginning of the 2nd century BCE, Pars was ruled by local dynasts subject to theHellenisticSeleucid Empire.[14]These dynasts held the ancient Persian title offrataraka( "leader, governor, forerunner" ), which is also attested in the Achaemenid-era.[15]Later under thefratarakaWadfradad II(fl. 138 BCE) was made a vassal of the IranianParthian (Arsacid) Empire.[14]Thefratarakawere shortly afterwards replaced by theKings of Persis,most likely at the accession of the Arsacid monarchPhraates II(r. 132–127 BCE).[16]Unlike thefratarakas,the Kings of Persis used the title ofshah( "king" ), and laid foundations to a new dynasty, which may be labelled the Darayanids.[16]

UnderVologases V(r. 191–208), the Parthian Empire was in decline, due to wars with theRomans,civil wars and regional revolts.[17]The Roman emperorSeptimius Severus(r. 193–211) had invaded the Parthian domains in 196, and two years later did the same, this time sacking the Parthian capital of Ctesiphon.[17]At the same time, revolts occurred inMediaand Persis.[17]The Iranologist Touraj Daryaee argues that the reign of Vologases V was "the turning point in Parthian history, in that the dynasty lost much of its prestige."[17]The kings of Persis were now unable to depend on their weakened Parthian overlords.[17]Indeed, in 205/6, Pabag rebelled and overthrew theBazrangidruler of Persis,Gochihr,taking Istakhr for himself.[18][17]Around 208Vologases VIsucceeded his father Vologases V as king of the Arsacid Empire. He ruled as the uncontested king from 208 to 213, but afterwards fell into a dynastic struggle with his brotherArtabanus IV,[b]who by 216 was in control of most of the empire, even being acknowledged as the supreme ruler by the Roman Empire.[19]Artabanus IV soon clashed with the Roman emperorCaracalla,whose forces he managed to contain atNisibisin 217.[20]

Peace was made between the two empires the following year, with the Arsacids keeping most ofMesopotamia.[20]However, Artabanus IV still had to deal with his brother Vologases VI, who continued to mint coins and challenge him.[20]The Sasanian family had meanwhile quickly risen to prominence in Pars, and had now under Ardashir begun to conquer the neighbouring regions and more far territories, such asKirman.[19][21]At first, Ardashir I's activities did not alarm Artabanus IV, until later, when the Arsacid king finally chose to confront him.[19]

Early life and co-rule

[edit]

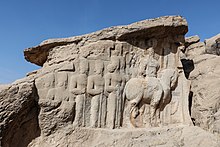

Shapur, as portrayed in the Sasanianrock reliefs,took part in his father's war with the Arsacids, including theBattle of Hormozdgan.[1]The battle was fought on 28 April 224, with Artabanus IV being defeated and killed, marking the end of the Arsacid era and the start of 427 years of Sasanian rule.[22]The chief secretary of the deceased Arsacid king,Dad-windad,was afterwards executed by Ardashir I.[23]Ardashir celebrated his victory by having two rock reliefs sculptured at the Sasanian royal city of Ardashir-Khwarrah (present-dayFiruzabad) inPars.[24][25]The first relief portrays three scenes of personal fighting; starting from the left, a Persian aristocrat seizing a Parthian soldier; Shapur impaling the Parthian minister Dad-windad with his lance; and Ardashir I ousting Artabanus IV.[25][22]The second relief, conceivably intended to portray the aftermath of the battle, displays the triumphant Ardashir I being given the badge of kingship over a fire shrine from theZoroastriansupreme godAhura Mazda,while Shapur and two other princes are watching from behind.[25][24]Ardashir considered Shapur "the gentlest, wisest, bravest and ablest of all his children", and nominated him as his successor in a council amongst the magnates.[1]

Military career

[edit]The Eastern Front

[edit]The Eastern provinces of the fledgling Sasanian Empire bordered on the land of theKushansand the land of theSakas(roughly today's Turkmenistan, Afghanistan and Pakistan). The military operations of Shapur's father Ardashir I had led to the local Kushan and Saka kings offering tribute, and satisfied by this show of submission, Ardashir seems to have refrained from occupying their territories.Al-Tabarialleges he rebuilt the ancient city ofZranginSakastan(the land of theSakas,Sistan), but the only early Sasanian period founding of a new settlement in the East which is certain is the building by Shapur I ofNishapur— "Beautiful (city built) by Shapur" —inDihistan(formerParthia,apparently lost by theParthiansto theKushans).[26]

Soon after the death of his father in 241 CE, Shapur felt the need to cut short the campaign they had started in Roman Syria, and reassert Sasanian authority in the East, perhaps because the Kushan and Saka kings were lax in abiding to their tributary status. However, he first had to fight "The Medes of the Mountains" —as we will see possibly in the mountain range ofGilanon the Caspian coast—and after subjugating them, he appointed his son Bahram (the laterBahram I) as their king. He then marched to the East and annexed most of the land of the Kushans, and appointing his sonNarsehas Sakanshah—king of the Sakas—inSistan.In 242 CE, Shapur conqueredkhwarezm.[27]Shapur could now proudly proclaim that his empire stretched all the way to Peshawar, and his relief inRag-i-Bibiin present-day Afghanistan confirms this claim.[28]Shapur I claims in hisNaqsh-e Rostaminscription possession of the territory of the Kushans (Kūšān šahr) as far as "Purushapura" (Peshawar), suggesting he controlledBactriaand areas as far as theHindu-Kushor even south of it:[29][full citation needed]

I, the Mazda-worshipping lord, Shapur, king of kings of Iran and An-Iran… (I) am the Master of the Domain of Iran (Ērānšahr) and possess the territory of Persis, Parthian… Hindestan, the Domain of the Kushan up to the limits of Paškabur and up to Kash, Sughd, and Chachestan.

— Naqsh-e Rostaminscription of Shapur I

He seems to have garrisoned the Eastern territories with POW's from his previous campaign against the Medes of the Mountains. Agathias claimsBahram II(274–293 CE) later campaigned in the land of the Sakas and appointed his brother Hormizd as its king. When Hormizd revolted, thePanegyrici Latinilist his forces as the Sacci (Sakas), the Rufii (Cusii/Kushans) and the Geli (Gelans /Gilaks,the inhabitants ofGilan). Since the Gilaks are obviously out of place among these easterners, and as we know that Shapur I had to fight the Medes of the Mountains first before marching to the land of the Kushans, it is conceivable those Gilaks were the descendants of warriors captured during Shapur I's North-western campaign, forcibly drafted into the Sasanian army, and settled as a hereditary garrison inMerv,Nishapur,orZrangafter the conclusion of Shapur's north-eastern campaign, the usual Sasanian practise with prisoners of war.[30]

First Roman war

[edit]

Ardashir I had, towards the end of his reign, renewed the war against theRoman Empire,and Shapur I had conquered theMesopotamianfortressesNisibisandCarrhaeand had advanced intoSyria.In 242, the Romans under the father-in-law of their child-emperorGordian IIIset out against the Sasanians with "a huge army and great quantity of gold," (according to a Sasanian rock relief) and wintered inAntioch,while Shapur was occupied with subduingGilan,Khorasan,andSistan.[31]There the Roman generalTimesitheusfought against the Sasanians and won repeated battles, and recaptured Carrhae and Nisibis, and at last routed a Sasanian army at Resaena, forcing the Persians to restore all occupied cities unharmed to their citizens. "We have penetrated as far as Nisibis, and shall even get toCtesiphon,"the young emperorGordian III,who had joined his father-in-law Timesitheus, exultantly wrote to the Senate.

The Romans later invaded eastern Mesopotamia but faced tough resistance from Shapur I who returned from the East.Timesitheusdied under uncertain circumstances and was succeeded byPhilip the Arab.The young emperor Gordian III went to theBattle of Misicheand was either killed in the battle or murdered by the Romans after the defeat. The Romans then chose Philip the Arab as Emperor. Philip was not willing to repeat the mistakes of previous claimants, and was aware that he had to return to Rome to secure his position with the Senate. Philip concluded a peace with Shapur I in 244; he had agreed that Armenia lay within Persia's sphere of influence. He also had to pay an enormous indemnity to the Persians of 500,000 gold denarii.[1]Philip immediately issued coins proclaiming that he had made peace with the Persians (pax fundata cum Persis).[32]However, Philip later broke the treaty and seized lost territory.[1]

Shapur I commemorated this victory on several rock reliefs inPars.

Second Roman war

[edit]Shapur I invaded Mesopotamia in 250 but again, serious trouble arose inKhorasanand Shapur I had to march over there and settle its affair.

Having settled the affair in Khorasan he resumed the invasion of Roman territories, and later annihilated a Roman force of 60,000 at theBattle of Barbalissos.He then burned and ravaged the Roman province ofSyriaand all its dependencies.

Shapur I then reconqueredArmenia,and incitedAnak the Parthianto murder the king of Armenia,Khosrov II.Anak did as Shapur asked, and had Khosrov murdered in 258; yet Anak himself was shortly thereafter murdered by Armenian nobles.[33]Shapur then appointed his sonHormizd Ias the "Great King of Armenia". With Armenia subjugated,Georgiasubmitted to the Sasanian Empire and fell under the supervision of a Sasanian official.[1]With Georgia and Armenia under control, the Sasanians' borders on the north were thus secured.

During Shapur's invasion ofSyriahe captured important Roman cities likeAntioch.The EmperorValerian(253–260) marched against him and by 257 Valerian had recovered Antioch and returned the province of Syria to Roman control. The speedy retreat of Shapur's troops caused Valerian to pursue the Persians toEdessa,but they weredefeated,and Valerian, along with the Roman army that was left, was captured by Shapur[34]Shapur then advanced intoAsia Minorand managed to captureCaesarea,[35]deporting hundred upon thousands of Roman citizens to the Sasanian empire.[36]He used these captive Roman citizens to build adykenearShushtar,called "Caesar's dyke".[36]

The victory over Valerian is presented in a mural atNaqsh-e Rustam,where Shapur is represented on horseback wearing royal armour and a crown. Before him kneels a man in Roman dress, asking for grace. The same scene is repeated in other rock-face inscriptions.[37] Christian tradition has Shapur I humiliating Valerian, infamous for hispersecution of Christians,by theKing of Kingsusing the Emperor as a footstool to mount his horse, and they claim he later died a miserable death in captivity at the hands of the enemy. However, just as with the above-mentionedGilaksdeported to the East by Shapur, the Persian treatment of prisoners of war was unpleasant but honourable, drafting the captured Romans and their Emperor into their army and deporting them to a remote place,BishapurinKhuzistan,where they were settled as a garrison and built a weir with bridge for Shapur.[38]

However, the Persian forces were later defeated by the Roman officerBalistaand the lord ofPalmyraSeptimius Odaenathus,who captured the royal harem. Shapur plundered the eastern borders of Syria and returned to Ctesiphon, probably in late 260.[1]In 264 Septimius Odaenathus reached Ctesiphon, but failed to take the city.[39][40]

TheColossal Statue of Shapur I,which stands in the Shapur Cave, is one of the most impressive sculptures of theSasanian Empire.

Interactions with minorities

[edit]Shapur is mentioned many times in theTalmud,in which he is referred to inJewish AramaicasShabur Malka(שבור מלכא), meaning "King Shapur". He had good relations with the Jewish community and was a friend ofShmuel,one of the most famous of theBabylonianAmoraim,the Talmudic sages from among the important Jewish communities ofMesopotamia.

Roman prisoners of war

[edit]Shapur's campaigns deprived the Roman Empire of resources while restoring and substantially enriching his own treasury, bydeportingmany Romans from conquered cities to Sasanian provinces likeKhuzestan,Asuristan,andPars.This influx of deported artisans and skilled workers revitalised Iran's domestic commerce.[1]

Death

[edit]InBishapur,Shapur died of an illness. His death came in May 270 and he was succeeded by his son,Hormizd I.Two of his other sons,Bahram IandNarseh,would also become kings of the Sasanian Empire, while another son,Shapur Meshanshah,who died before Shapur, sired children who would hold exalted positions within the empire.[1]

Government

[edit]Governors during his reign

[edit]

Under Shapur, the Sasanian court, including its territories, were much larger than that of his father. Several governors and vassal-kings are mentioned in his inscriptions; Ardashir, governor ofQom;Varzin, governor ofSpahan;Tiyanik, governor ofHamadan;Ardashir, governor of Neriz; Narseh, governor of Rind; Friyek, governor ofGundishapur;Rastak, governor ofVeh-Ardashir;Amazasp III,king ofIberia.Under Shapur several of his relatives and sons served as governor of Sasanian provinces;Bahram,governor ofGilan;Narseh,governor ofSindh,SakastanandTuran;Ardashir, governor ofKirman;Hormizd-Ardashir,governor ofArmenia;Shapur Meshanshah,governor ofMeshan;Ardashir, governor ofAdiabene.[41]

Officials during his reign

[edit]Several names of Shapur's officials are carved on his inscription atNaqsh-e Rustam.Many of these were the offspring of the officials who served Shapur's father. During the reign of Shapur, a certain Papak served as the commander of the royal guard (hazarbed), while Peroz served as the chief of the cavalry (aspbed); Vahunam and Shapur served as the director of the clergy; Kirdisro served as viceroy of the empire (bidaxsh); Vardbad served as the "chief of services"; Hormizd served as the chief scribe; Naduk served as "the chief of the prison"; Papak served as the "gate keeper"; Mihrkhwast served as the treasurer; Shapur served as the commander of the army; Arshtat Mihran served as the secretary; Zik served as the "master of ceremonies".[42]

Army

[edit]

Under Shapur, the Iranian military experienced a resurgence after a rather long decline in the 2nd and 3rd centuries, which gave the Romans the opportunity to undertake expeditions into the Near East and Mesopotamia during the end of the Parthian Empire.[43]Yet, the military was essentially the same as that of the Parthians; the same Parthians nobles who served the Arsacid royal family, now served the Sasanians, forming the majority of the Sasanian army.[44]However, the Sasanians seem to have employed morecataphractswho were equipped with lighter chain-mail armour resembling that of the Romans.[44]

Although Iranian society was greatly militarised and its elite designated themselves as a "warrior nobility" (arteshtaran), it still had a significantly smaller population, was more impoverished, and was a less centralised state compared to the Roman Empire.[44]As a result, the Sasanian shahs had access to fewer full-time fighters, and depended on recruits from the nobility instead.[44]Some exceptions were the royal cavalry bodyguard, garrison soldiers, and units recruited from places outside Iran.[44]The bulk of the nobility included the powerful Parthian noble families (known as thewuzurgan) that were centred on theIranian plateau.[45]They served as the backbone of the Sasanianfeudalarmy and were largely autonomous.[45]The Parthian nobility worked for the Sasanian shah for personal benefit, personal oath, and, conceivably, a common awareness of the "Aryan" (Iranian) kinship they shared with their Persian overlords.[45]

Use ofwar elephantsis also attested under Shapur, who made use of them to demolish the city ofHatra.[46]He may also have used them against Valerian, as attested in theShahnameh(The Book of Kings).[47]

Monuments

[edit]

Shapur I left other reliefs and rock inscriptions. A relief atNaqsh-e RajabnearEstakhris accompanied by a Greek translation. Here Shapur I calls himself "theMazdayasnan(worshipper ofAhuramazda), the divine Shapur, King of Kings of theIranians,and non-Iranians, of divine descent, son of the Mazdayasnan, the divineArdashir,King of Kings of the Aryans, grandson of the divine kingPapak".Another long inscription at Estakhr mentions the King's exploits in archery in the presence of his nobles.

From his titles we learn that Shapur I claimed sovereignty over the whole earth, although in reality his domain extended little farther than that of Ardashir I. Shapur I built the great townGundishapurnear the old Achaemenid capitalSusa,and increased the fertility of the district with a dam and irrigation system—built by Roman prisoners—that redirected part of theKarun River.The barrier is still calledBand-e Kaisar,"the mole of the Caesar". He is also responsible for building the city ofBishapur,with the labours of Roman soldiers captured after the defeat of Valerian in 260. Shapur also built a town namedPushanginKhorasan.

Religious policy

[edit]In all records Shapur calls himselfmzdysn( "Mazda-worshipping" ). His inscription at theKa'ba-ye Zartoshtrecounts his wars and religious establishments to the same extent. He believed that he had a responsibility; "For the reason, therefore, that the gods have so made us their instrument (dstkrt), and that by the help of the gods we have sought out for ourselves, and hold, all these nations (štry) for that reason we have also founded, province by province, many Varahrān fires (ʾtwry wlhlʾn), and we have dealt piously with many Magi (mowmard), and we have made great worship of the gods."[1]According to the Zoroastrian priestKartir,Shapur treated the Zoroastrians generously, and permitted members of their clergy to follow him on his expeditions against the Romans.[1]According to the historianProds Oktor Skjærvø,Shapur was a "lukewarm Zoroastrian".[48]

During the reign of Shapur,Manichaeism,a new religion founded by the Iranian prophetMani,flourished. Mani was treated well by Shapur, and in 242, the prophet joined the Sasanian court, where he tried to convert Shapur by dedicating his only work written inMiddle Persian,known as theShabuhragan.Shapur, however, did not convert to Manichaeism and remained a Zoroastrian.[49]

Coinage and imperial ideology

[edit]

While the titulage of Ardashir was "King of Kings of Iran(ians)", Shapur slightly changed it, adding the phrase "and non-Iran(ians)".[50]The extended title demonstrates the incorporation of new territory into the empire, however what was precisely seen as "non-Iran(ian)" (aneran) is not certain.[51]Although this new title was used on his inscriptions, it was almost never used on hiscoinage.[52]The title first became regularised under Hormizd I.[53]

Cultural depictions

[edit]Shapur appears inHarry Sidebottom's historical fiction novel series as one of the enemies of the series protagonist Marcus Clodius Ballista, career soldier in a third-century Roman army.

See also

[edit]- Shapour I's inscription in Ka'ba-ye Zartosht

- Shapour I's inscription in Naqsh-e Rostam

- Siege of Dura Europos (256)

Notes

[edit]- ^Also spelled "King of Kings of Iranians and non-Iranians".

- ^Artabanus IV is erroneously known in older scholarship as Artabanus V. For further information, seeSchippmann (1986a,pp. 647–650)

References

[edit]- ^abcdefghijklmnShahbazi 2002.

- ^Mark, Joshua J."Shapur I".World History Encyclopedia.Retrieved17 December2023.

- ^Bonner 2020,p. 25.

- ^abStoneman, Erickson & Netton 2012,p. 12.

- ^abBonner 2020,p. 49.

- ^Shahbazi, A. Shapur (2002). "Šāpur I". Encyclopaedia Iranica.

- ^Brosius, Maria (2000). "Women i. In Pre-Islamic Persia".Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol.London et al.

- ^Bonner, Michael (2020).The Last Empire of Iran.New York: Gorgias Press. pp. 1–406.ISBN978-1463206161

- ^Gignoux 1994,p. 282.

- ^abOlbrycht 2016,pp. 23–32.

- ^Daryaee 2010,p. 242.

- ^abRezakhani 2017b,pp. 44–45.

- ^abcWiesehöfer 2000a,p. 195.

- ^abWiesehöfer 2009.

- ^Wiesehöfer 2000b,p. 195.

- ^abShayegan 2011,p. 178.

- ^abcdefDaryaee 2010,p. 249.

- ^Daryaee 2012,p. 187.

- ^abcSchippmann 1986a,pp. 647–650.

- ^abcDaryaee 2014,p. 3.

- ^Schippmann 1986b,pp. 525–536.

- ^abShahbazi 2004,pp. 469–470.

- ^Rajabzadeh 1993,pp. 534–539.

- ^abShahbazi 2005.

- ^abcMcDonough 2013,p. 601.

- ^Thaalibi 485–486 even ascribes the founding of Badghis and Khwarazm to Ardashir I

- ^Frye, Richard N.(1983)."The political history of Iran under the Sasanians".The Cambridge History of Iran: The Seleucid, Parthian, and Sasanian periods (1). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 116–181.ISBN978-0521246934.

- ^W. Soward, "The Inscription Of Shapur I At Naqsh-E Rustam In Fars", sasanika.org, 3.

Cf. F. Grenet, J. Lee, P. Martinez, F. Ory, “The Sasanian Relief at Rag-i Bibi (Northern Afghanistan)” in G. Hermann, J. Cribb (ed.), After Alexander. Central Asia before Islam (London 2007), pp. 259–260 - ^Rezakhani 2017a,pp. 202–203.

- ^Agathias 4.24.6–8; Panegyrici Latini N3.16.25; Thaalibi 495;Arthur Christensen (1944).L'Iran sous les Sassanides.Copenhague. p. 214.

{{cite book}}:CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^Raditsa 2000,p. 125.

- ^Southern 2003,p. 71.

- ^Hovannisian,The Armenian People From Ancient to Modern Times, Volume I: The Dynastic Periods: From Antiquity to the Fourteenth Century,p. 72

- ^Frye 2000,p. 126.

- ^Henning 1939,p. 842.

- ^abHenning 1939,p. 843.

- ^Grishman, R. (1995).Iran From the Beginning Until Islam.

- ^A. Tafazzoll (1990).History of Ancient Iran.p. 183.

- ^Who's Who in the Roman WorldBy John Hazel

- ^Babylonia Judaica in the Talmudic PeriodBy A'haron Oppenheimer, Benjamin H. Isaac, Michael Lecker

- ^Frye 1984,p. 299.

- ^Frye 1984,p. 373.

- ^Daryaee & Rezakhani 2017,p. 157.

- ^abcdeMcDonough 2013,p. 603.

- ^abcMcDonough 2013,p. 604.

- ^Daryaee 2014,p. 46.

- ^Daryaee 2016,p. 37.

- ^Skjærvø 2011,pp. 608–628.

- ^Marco Frenschkowski (1993). "Mani (iran. Mānī<; gr. Μανιχαῑος < ostaram. Mānī ḥayyā" der lebendige Mani ")". In Bautz, Traugott (ed.).Biographisch-Bibliographisches Kirchenlexikon (BBKL)(in German). Vol. 5. Herzberg: Bautz. cols. 669–680.ISBN3-88309-043-3.

- ^Shayegan 2013,p. 805.

- ^Shayegan 2004,pp. 462–464.

- ^Curtis & Stewart 2008,pp. 21, 23.

- ^Curtis & Stewart 2008,p. 21.

Sources

[edit]- Al-Tabari, Abu Ja'far Muhammad ibn Jarir(1985–2007). Ehsan Yar-Shater (ed.).The History of Al-Ṭabarī.Vol. 40 vols. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

- Bonner, Michael (2020).The Last Empire of Iran.New York: Gorgias Press. pp. 1–406.ISBN978-1-4632-0616-1.

- Brosius, Maria (2000). "Women i. In Pre-Islamic Persia".Encyclopaedia Iranica.London et al.

{{cite encyclopedia}}:CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Curtis, Vesta Sarkhosh; Stewart, Sarah (2008).The Sasanian Era.I.B. Tauris. pp. 1–200.ISBN978-0-85771-972-0.

- Daryaee, Touraj(2014).Sasanian Persia: The Rise and Fall of an Empire.I.B.Tauris. pp. 1–240.ISBN978-0-85771-666-8.

- Daryaee, Touraj (2010)."Ardashir and the Sasanians' Rise to Power".Anabasis.University of California: 236–255.

- Daryaee, Touraj(2012). "The Sasanian Empire". In Daryaee, Touraj (ed.).The Oxford Handbook of Iranian History.Oxford University Press. pp. 224–651.ISBN978-0-19-973215-9.

- Daryaee, Touraj (2016). "From Terror to Tactical Usage: Elephants in the Partho-Sasanian Period". In Curtis, Vesta Sarkhosh; Pendleton, Elizabeth J.; Alram, Michael; Daryaee, Touraj (eds.).The Parthian and Early Sasanian Empires: Adaptation and Expansion.Oxbow Books.ISBN978-1-78570-208-2.

- Daryaee, Touraj; Rezakhani, Khodadad (2017). "The Sasanian Empire". In Daryaee, Touraj (ed.).King of the Seven Climes: A History of the Ancient Iranian World (3000 BCE – 651 CE).UCI Jordan Center for Persian Studies. pp. 1–236.ISBN978-0-692-86440-1.

- Daryaee, Touraj(2018)."Res Gestae Divi Saporis".In Nicholson, Oliver (ed.).The Oxford Dictionary of Late Antiquity.Oxford: Oxford University Press.ISBN978-0-19-866277-8.

- Frye, Richard Nelson(1984).The History of Ancient Iran.C.H. Beck. pp.1–411.ISBN978-3-406-09397-5.

- Frye, R.N. (2000). "The Political History of Iran under the Sasanians". In Yarshater, Ehsan (ed.).Cambridge History of Iran.Vol. 3, Part 1: The Seleucid, Parthian, and Sasanian periods. Cambridge University Press.

- Gignoux, Ph. (1983)."Ādur-Anāhīd".Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. I, Fasc. 5.London et al. p. 472.

{{cite encyclopedia}}:CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Gignoux, Philippe (1994). "Dēnag".Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. VII, Fasc. 3.p. 282.

- Henning, W. B. (1939)."The Great Inscription of Šāpūr I".Bulletin of the School of Oriental Studies.9(4). Cambridge University Press: 823–849.

- Kia, Mehrdad (2016).The Persian Empire: A Historical Encyclopedia.ABC-CLIO.ISBN978-1-61069-391-2.(2 volumes)

- McDonough, Scott (2011). "The Legs of the Throne: Kings, Elites, and Subjects in Sasanian Iran". In Arnason, Johann P.; Raaflaub, Kurt A. (eds.).The Roman Empire in Context: Historical and Comparative Perspectives.John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. pp. 290–321.doi:10.1002/9781444390186.ch13.ISBN978-1-4443-9018-6.

- McDonough, Scott (2013)."Military and Society in Sasanian Iran".In Campbell, Brian; Tritle, Lawrence A. (eds.).The Oxford Handbook of Warfare in the Classical World.Oxford University Press. pp. 1–783.ISBN978-0-19-530465-7.

- Olbrycht, Marek Jan (2016). "Dynastic Connections in the Arsacid Empire and the Origins of the House of Sāsān". In Curtis, Vesta Sarkhosh; Pendleton, Elizabeth J.; Alram, Michael; Daryaee, Touraj (eds.).The Parthian and Early Sasanian Empires: Adaptation and Expansion.Oxbow Books.ISBN978-1-78570-208-2.

- Pourshariati, Parvaneh (2008).Decline and Fall of the Sasanian Empire: The Sasanian-Parthian Confederacy and the Arab Conquest of Iran.London and New York: I.B. Tauris.ISBN978-1-84511-645-3.

- Rajabzadeh, Hashem (1993). "Dabīr".Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. VI, Fasc. 5.pp. 534–539.

- Rapp, Stephen H. (2014).The Sasanian World through Georgian Eyes: Caucasia and the Iranian Commonwealth in Late Antique Georgian Literature.Ashgate Publishing, Ltd.ISBN978-1-4724-2552-2.

- Rezakhani, Khodadad (2017a). "From the Kushans to the Western Turks". In Daryaee, Touraj (ed.).King of the Seven Climes: A History of the Ancient Iranian World (3000 BCE – 651 CE).UCI Jordan Center for Persian Studies. pp. 199–227.ISBN978-0-692-86440-1.

- Rezakhani, Khodadad (2017b).ReOrienting the Sasanians: East Iran in Late Antiquity.Edinburgh University Press.ISBN978-1-4744-0030-5.JSTOR10.3366/j.ctt1g04zr8.

- Schindel, Nikolaus (2013). "Sasanian Coinage". In Potts, Daniel T. (ed.).The Oxford Handbook of Ancient Iran.Oxford University Press.ISBN978-0-19-973330-9.

- Raditsa, Leo (2000). "Iranians in Asia Minor". In Yarshater, Ehsan (ed.).The Cambridge History of Iran.Vol. 3, Part 1: The Seleucid, Parthian and Sasanian Periods. Cambridge University Press. pp. 100–115.

- Schippmann, K. (1986a). "Artabanus (Arsacid kings)".Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. II, Fasc. 6.pp. 647–650.

- Schippmann, K. (1986b). "Arsacids ii. The Arsacid dynasty".Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. II, Fasc. 5.pp. 525–536.

- Schmitt, R. (1986)."Artaxerxes".Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. II, Fasc. 6.pp. 654–655.

- Shahbazi, A. Shapur(1988)."Bahrām I".Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. III, Fasc. 5.pp. 514–522.

- Shahbazi, A. Shapur (2002). "Šāpur I".Encyclopaedia Iranica.

- Shahbazi, A. Shapur (2004). "Hormozdgān".Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. XII, Fasc. 5.pp. 469–470.

- Shahbazi, A. Shapur (2005)."Sasanian dynasty".Encyclopaedia Iranica, Online Edition.

- Shayegan, M. Rahim (2004)."Hormozd I".Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. XII, Fasc. 5.pp. 462–464.

- Shayegan, M. Rahim (2011).Arsacids and Sasanians: Political Ideology in Post-Hellenistic and Late Antique Persia.Cambridge University Press.ISBN978-0-521-76641-8.

- Shayegan, M. Rahim (2013). "Sasanian Political Ideology". In Potts, Daniel T. (ed.).The Oxford Handbook of Ancient Iran.Oxford University Press.ISBN978-0-19-973330-9.

- Skjærvø, Prods Oktor (2011). "Kartir".Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. XV, Fasc. 6.pp. 608–628.

- Stausberg, Michael;Vevaina, Yuhan Sohrab-Dinshaw; Tessmann, Anna (2015).The Wiley Blackwell Companion to Zoroastrianism.John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

- Stoneman, Richard; Erickson, Kyle; Netton, Ian Richard (2012).The Alexander Romance in Persia and the East.Barkhuis.ISBN978-94-91431-04-3.

- Southern, Pat (2003).The Roman Empire from Severus to Constantine.Taylor & Francis.

- Vevaina, Yuhan; Canepa, Matthew (2018)."Ohrmazd".In Nicholson, Oliver (ed.).The Oxford Dictionary of Late Antiquity.Oxford: Oxford University Press.ISBN978-0-19-866277-8.

- Weber, Ursula (2016). "Narseh".Encyclopaedia Iranica.

- Wiesehöfer, Josef(1986). "Ardašīr I i. History".Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. II, Fasc. 4.pp. 371–376.

- Wiesehöfer, Josef (2000b)."Frataraka".Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. X, Fasc. 2.p. 195.

- Wiesehöfer, Josef (2000a)."Fārs ii. History in the Pre-Islamic Period".Encyclopaedia Iranica.

- Wiesehöfer, Josef (2001).Ancient Persia.I.B. Tauris.ISBN978-1-86064-675-1.

- Wiesehöfer, Josef (2009)."Persis, Kings of".Encyclopaedia Iranica.