Shenyi

| Shenyi | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Modern reproduction of a Confucian shenyi. | |||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||

| Chinese | Thâm y | ||||||||

| Literal meaning | Deep clothing | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Vietnamese name | |||||||||

| Vietnamese alphabet | Áo thâm y | ||||||||

| Hán-Nôm | Áo thâm y | ||||||||

| Korean name | |||||||||

| Hangul | 심의 | ||||||||

| Hanja | Thâm y | ||||||||

| Literal meaning | Profound gown | ||||||||

| |||||||||

Shenyi(Chinese:Thâm y;pinyin:shēnyī;lit.'deep clothing';Korean:심의;Hanja:Thâm y;RR:Simui;yr:sim.ui), also calledDeep garmentin English,[1]: 12 [2]: 135 means "wrapping the body deep within the clothes"[1]: 12 or "to wrap the body deep within cloth".[2]: 135 Theshenyiis an iconic form ofrobeinHanfu,[3]which was recorded inLijiand advocated inZhu Xi'sZhuzi jiali《 chu tử gia lễ 》.[4]As cited in theLiji,theshenyiis a long robe which is created when the"upper half is connected to the bottom half to cover the body fully".[3]Theshenyi,along with its components,[5]existed prior to theZhou dynasty[6][7]and appeared at least since theShang dynasty.[3]Theshenyiwas then developed in Zhou dynasty with a complete system of attire, being shaped by the Zhou dynasty's strict hierarchical system in terms of social levels, gender, age, and situation and was used as a basic form of clothing.[3]Theshenyithen became the mainstream clothing choice during theQinandHan dynasties.[3]By the Han dynasty, theshenyihad evolved into two types of robes: thequjupao(Chinese:Khúc cư bào) and thezhijupao(Chinese:Trực cư bào).[1]: 13–14 Theshenyilater gradually declined in popularity around theWei,Jin,andNorthern and Southern dynastiesperiod.[3]However, theshenyi's influence persisted in the following dynasties.[3]Theshenyithen became a form of formal wear forscholar-officialsin theSongandMing dynasties.[8]Chinese scholars also recorded and defined the meaning ofshenyisince the ancient times, such asZhu Xiin the Song dynasty,Huang Zongxiin the Ming dynasty, and Jiang Yong in theQing dynasty.[3]

Theshenyiwas also introduced in bothGoryeoandJapan,where it exerted influences onConfucianclothing attire inKoreaand Japan. Theshenyiis calledsimuiin Korean, it was worn by followers of Confucianism in theGoryeoandJoseonperiod.[6][9]

Terminology[edit]

The termshenyi(Chinese:Thâm y) is composed of two Chinese characters《Thâm》which can be translated as 'deep' and《Y》which literally means 'clothing' in the broad sense. Combined, the termshenyiliterally means "deep clothing".

Construction and designs[edit]

The structure of theHanfusystem is typically composed of upper and lower parts; it also typically comes into two styles: one-piece garment (where the upper and lower parts are connected together), and two-pieces garments (where the upper and lower parts are not connected).[3][10]

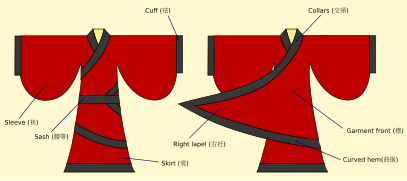

And as stated by theLiji,theshenyiwas one long robe as opposite to the combination of a top and a bottom.[11]However, the structure of theshenyiis made of two pieces: an upper garment calledyi(Chinese:Y;pinyin:yī) and lower garment calledchang(Chinese:Thường;pinyin:cháng), which are then connected together to form a one-piece robe.[3][1]: 12 Thus, theshenyidiffer structurally from thepaofu,which is a one-piece robe where the lower and upper part is cut in a single fabric. Moreover, a standardshenyiwas also made up of twelve panel of fabric which were sewn together.[12]

History of early development[edit]

Theshenyi,along with its components,[5]already existed prior to theZhou dynasty[6][7]having first appeared at least since theShang dynasty.[3]However, in the Shang andWestern Zhou dynasties,people prominently wore a set of attire calledyichang,which consisted of ajacketcalledyiand a longskirtcalledchang.[12][13]Out of convenience, theyiandchangwere sewn together to form a robe;[14]this combination then resulted into theshenyiwhich was developed in theZhou dynasty.[15][5]Theshenyieventually became the dominant form ofHanfurobe from theZhou dynastyto theHan dynastyremaining popular;[14][16]: 260 From theSpring and Autumn periodto the Han dynasty, the looseshenyiwith wide sleeves was fashionable amongst the members of the royal families, the aristocrats, and the elites.[17]The looseshenyiwhich wrapped around the body to back and lacked a front end slit and was designed for the upper classes of society, especially for women, who wanted to avoid exposing their body parts when walking.[17]This design of this wrap-style ofshenyiwas an important necessity in a period where thekunhad yet to become popular amongst the general population.[18]: 16 The preoccupation of the elites with layered, loose-fitting clothing also displayed their desire to distance themselves from the labourers, signalling their high status.[17]By theHan dynasty,theshenyihad evolved in forms;[1]: 12 it then further developed in the Han dynasty where small variations in styles and shapes appeared.[12][14]Following the Han dynasty, theshenyilost popularity in the succeeding dynasties until it was revived again theSong dynasty.[10][19]

Zhou dynasty period[edit]

TheWestern Zhou dynastyhad strict rules and regulations which regulated the daily attire of its citizen based on their social status; these regulations also governed the material, shape, sizes, colours, and decorative patterns of their garments.[16]: 255 Theshenyiwas also shaped by the Zhou dynasty's hierarchical system based on social class, gender, age, and the situation.[3]However, despite these complex regulations, theshenyiwas still a basic form of garment which served the needs for all classes, from nobles to commoners, old to young, men to women; and people would therefore expressed their identities through recognizable objects, decorations, colours, and materials on their outer garments.[3]Nobles would wear a decorated coat over theshenyi,while commoners would wear it alone.[3]

Spring and Autumn period and Warring States period[edit]

In the earlyEastern Zhou dynastyperiod, there were still strict rules and regulations which regulated the clothing of all social classes and were used to maintain social distinction between people of different classes.[11]

In theWarring States period,theshenyiwas a moderately formal style of clothing.[1]: 13 Theshenyiwhich was representative of the Warring States Period, was designed to have the front stretched and wrapped around the body several times.[17]The wrapping-styleshenyifor men and women can be seen in theSilk painting depicting a man riding a dragonand theSilk painting with female figure, dragon and phoenix patternsrespectively[18]: 16–17 Both paintings unearthed from aChutomb, Warring States period, 5th century BC, Changsha, Hunan Province.[20][21]

Materials which were used in this period tended to be linen; however, when theshenyiwas made into ceremonial garments, then black silk would be used instead.[1]: 13 It was worn by both the literati and the warriors as it was both functional and simplistic in style.[1]: 13 Theshenyiwas also tied right below the waist level in the front with a silk ribbon, calleddadai(Chinese:Đại đái) orshendai(Chinese:Thân đái), on which a decorative piece was attached to.[1]: 13 [22]

Rules and regulations in theLiji[edit]

The design features ofshenyialso match the ancientChinese culture.[23]In this period, theshenyiwas also deeply rooted in the traditional Chinese ethics and morals which forbid close contacts between males and females.[1]: 12 In this period, theshenyihad to conform to the certain rules and regulations which were recorded in the special chapter calledShenyi《 thâm y 》in theLiji.[1]: 12 [22]According to theLiji,the ancientshenyihad to fulfill the following:[22]

[Ancient shenyi] had definite measurements, so as to satisfy the requirements of the compass and square, the line, the balance, and the steelyard. It was not made so short as to show any of the skin, nor so long as to touch the ground. The outside pieces of the skirt joined, and were hooked together at the side; (the width of) the seam at the waist was half that at the bottom (of the skirt). The sleeve was joined to the body of the dress at the armpit, so as to allow the freest movement of the elbow-joint; the length of the lower part admitted of the cuffs being turned back to the elbow. The sash was put on where there were no bones, so as not to interfere with the action of the thighs below or of the ribs above. [《 cổ giả thâm y, cái hữu chế độ, dĩ ứng quy, củ, thằng, quyền, hành. Đoản vô kiến phu, trường vô bị thổ. Tục nhẫm, câu biên. Yếu phùng bán hạ; cách chi cao hạ, khả dĩ vận trửu; mệ chi trường đoản, phản truất chi cập trửu. Đái hạ vô yếm bễ, thượng vô yếm hiếp, đương vô cốt giả. 》]

— Translated by James Legge, Liji: Shenyi《 thâm y 》

The same chapter described theshenyias being made of twelve panels of fabric corresponding to the twelve months and all twelve robes are cut into one clothing style.[22]Moreover, the shape of the component of theshenyiis also described:[22]

In the making (of the garment) twelve strips (of the cloth) were used, to correspond to the twelve months. The sleeve was made round, as if fashioned by a disk. The opening at the neck was square, as if made by means of that instrument so named. The cord-like (seam) at the back descended to the ankles, as if it had been a straight line. The edge at the bottom was like the steelyard of a balance, made perfectly even. [《 chế: Thập hữu nhị phúc dĩ ứng thập hữu nhị nguyệt; mệ hoàn dĩ ứng quy; khúc giáp như củ dĩ ứng phương; phụ thằng cập hõa dĩ ứng trực; hạ tề như quyền hành dĩ ứng bình. 》]

— Translated by James Legge, Liji: Shenyi《 thâm y 》

These prescribed rules and regulations did not only defined theshenyias the combination of theyiandchangtogether, but also prescribed the length of theshenyiin this period which had to be long enough to prevent the exposure of the skin but short enough to prevent it from trailing on the floor,[1]: 12–13 and the explanation behind the function of these prescribed measurements, and the location of the belt referred asdai(simplified Chinese:Đái;traditional Chinese:Đái).[22]It also prescribed the rules on the colours and decorations of the trims based on the circumstances of its wearer:[22]

For ornament, while his parents and grandparents were alive, (a son) wore the dress with its border embroidered. If (only) his parents were alive, the ornamental border was blue. In the case of an orphan son, the border was white. The border round the mouth of the sleeves and all the edges of the dress was an inch and a half wide. [《 cụ phụ mẫu, đại phụ mẫu, y thuần dĩ hội; cụ phụ mẫu, y thuần dĩ thanh. Như cô tử, y thuần dĩ tố. Thuần mệ, duyên, thuần biên, quảng các thốn bán. 》]

— Translated by James Legge, Liji: Shenyi《 thâm y 》

Moreover, in addition to the prescribed rules and regulations present in the chapterShenyi《 thâm y 》, more details can be found in the chapterYuzao《 ngọc tảo 》of theLijiwhich described theshenyias having ayourenopening,[11]and being a one-piece long robe with broad sleeve openings; with its circumference at the waist be three times that of the sleeve-opening and that of its hem be even larger:[24]

In the morning they wore thexuanduan;in the evening, the shenyi. [The shenyi] at the waist was thrice the width of the sleeve; and at the bottom twice as wide as at the waist. It was gathered in at each side (of the body). The sleeve could be turned back to the elbow. The outer or under garment joined on to the sleeve and covered a cubit of it. The collar was 2 inches wide; the cuff, a cubit and 2 inches long; the border, 1.5 inch broad. To wear silk under or inside linen was contrary to rule. [《 triều huyền đoan, tịch thâm y. Thâm y tam khư, phùng tề bội yếu, nhẫm đương bàng, mệ khả dĩ hồi trửu. Trường trung kế yểm xích. Giáp nhị thốn, khư xích nhị thốn, duyên quảng thốn bán. Dĩ bạch khỏa bố, phi lễ dã. 》]

— Translated by James Legge, Liji:《 ngọc tảo - Yu Zao》

There are two purposes for the loose-cut design: firstly, the body shape is less visible to others; the second reason is to allow the wearer to move the body as freely as possible. The wearer's skin should be appropriately covered to meet the first purpose. The waistband should only accentuate the outline of the waist; the outline of the rest of the body should be well hidden from view.[23]Nonetheless, the second purpose, which engages more freedom of movement for the wearer's body.

Cultural significance and symbolism[edit]

In the chapterShenyi《 thâm y 》of theLiji,the making of theshenyiwill match the compass calledgui(Chinese:Quy;lit.'pair of compass'), the square calledju(Chinese:Củ;lit.'try square'), the plumb line calledsheng(Chinese:Thằng;lit.'plumb bob'), and thesteelyard balancecalledquanheng(Chinese:QuyềnHành;lit.'balance scale').[22][25]These four tools have normative connotations inLiji:Thegui,ju,andshenggenerally refer to the rules and standards people should follow; thequanhengdefines the ability to balance all the advantages and disadvantages and result in the best solution.[23]

In appearance, rounded cuffs of theshenyito match the compass; squared neckline to match the squareness, the seams at the back part of theshenyidrop down to the ankle to match the straightness, and steelyard balance the bottom edge to match evenness. The terms "squareness," "straightness," and "evenness" can be used to describe both the physical properties of objects and the moral qualities of people. These wordplays tie the physical properties of tools to virtues. Every part ofshenyihas the attributes of an instrument, which gives the text multiple moral meanings.[23]

TheLijialso explains how theshenyihelps construct its wearer's character through the symbolic relationship between the tools, virtues, and each part of theshenyi.The circular shape of the cuffs allows the user to raise his arms while walking, allowing him to maintain correct comportment (rong). The straight seams worn in the rear (fusheng) and the square neckline worn in the front (baofang) are intended to straighten one's approach to political issues. The bottom edge is meant to seem like a steelyard balance to calm one's thoughts and focus one's aim.[23]

The back seam of theshenyiis first linked to the physical characteristics of "straightness" in theshengand then to the moral trait of "straightness." When attention to political matters, the wearer of theshenyiwill be straight in the sense of becoming "upright" the design of the square-shaped neckline indicates "making correct" correspondence to the wearer's role performance. The evenness of the bottom edge is supposed to be able to keep the wearer's thoughts "even" in the sense of "balancing," allowing him to focus on a single goal.[23]Lijiemphasizes how each part ofshenyirepresents a moral trait, such as selflessness, straightness, and evenness.

Nevertheless, the chapterShenyi《 thâm y 》also emphasizes the body effects on wearers. The body concealing and physical movement freedom are two significant reasons whyshenyiwas made in this design. Body mobility is brought up again inLiji,which says that the cuffs are created round to allow the wearer to cultivate his physical comportments (rong), not because roundness indicates a certain moral quality. In early Confucian ethics, having refined body comportment is regarded ethically significant.[23]Theshenyiallows the user to cultivate a person's comportment while also cultivating one's character by allowing a broad range of body mobility.

TheLijialso implies that the symbolic meanings of theshenyiwhich may be sensed by the wearer's body, in addition to being accessed cognitively and mentally. Both the Chinese verbs "to carry" (fu) and "to embrace" (bao) employed regarding the straight seams and square-shaped neckline frequently indicate a close bodily relationship between its subject and object. These two words are widely used to describe how the human body moves. The text implies that the wearer's body carries and embraces the straightness and squareness. Therefore, it can be sensed through the tactile sensations when theshenyicontacts the wearer's skin. Moreover, the evenness of the bottom border of theshenyimay be sensed when the wearer stretches it with his hands or when his thighs naturally meet it while walking.[23]The users ofshenyimay need to walk smoothly and firmly to keep its bottom edge even.

The design of theshenyialso encourages its wearer to use their bodies in a certain way. The fact that the text alternates between explaining the moral characteristics that theshenyirepresents and discussing how it links to the wearer's body indicates that the design ofshenyihas considered both thephysiologicalandpsychological-cognitiveeffects it has on its wearer.[23]

Mid-warring states period[edit]

By the Mid-warring states period, however, the rules and regulations started to disintegrate.[11]This can be observed in theMashantombs, where a lady, who was a member of theshiclass,[note 1]was buried sometimes around the year 340 – 278 BC with twelve long robes which were all cut in the approximate style ofshenyiwhether they were padded with silk floss (mianpao), single in layer (danyi) or lined (jiayi).[11]The forms of theseshenyi,however, were not standardized and show variations in cut and construction.[11]Moreover, some of the textiles and decorations used in making those robes were against the rules and regulations for her ranks and violated the rules which were stipulated in theLiji.[11]Theshenyifound in theMashantombs had a straight-front which falls straight down.[11]

Transition from Warring States period to the Han dynasty[edit]

Theshenyigrew in popularity during the transition period from theWarring States periodto theWestern Han dynasty;and with its increased in popularity, the shape of theshenyideviated further from its earlier prescriptions.[11][note 2]During theQinandHan dynasties,theshenyidominated the connection method of the upper and lower parts and became the mainstream choice.[3]

Qin dynasty[edit]

In theQin dynasty,Qin Shi Huangabolished themianfu-system of the Zhou dynasty and implemented theshenyi-system specifying that third ranked officials and above were required to wearshenyimade out green silk while commoners had to wearshenyiwhich were white in colour.[26]: 16 This system adopted by Qin Shi Huang laid the foundations of theHanfu-system in the succeeding dynasties.[26]: 16

Han dynasty[edit]

TheWestern Han dynastyalso implemented theshenyi-system, which featured the use of a cicada-shaped hat, red clothes, and a collar in the shape oftian《Điền》, and garments which were sewn in theshenyi-style with an upper and lower garment sewed together.[27]Theshenyiwas also worn together with theguanand shoes as a form of formal attire in the Han dynasty while in ordinary times,shankuattire and theruqunattire were born by men and women respectively.[26]: 16

By the Western Han Dynasty, the shape of theshenyihad deviated from the earlier versions as it can be found in theMawangduitomb of the same period belonging toLady Dai.[11]Theshenyihad evolved into two types of robe: thequjupao(Chinese:Khúc cư bào;lit.'curved robe'), which is also known as "curved gown" in English, and thezhijupao(Chinese:Trực cư bào;lit.'straight robe').[1]: 13–14 These two robes differed from each other based on their front opening and the way their lapels overlapped: thequjupaowould curve and wraps the dress to the back while the front opening of thezhijupaowould fall straight down.[11]Thequjupaodirectly evolved from the wrapping-styleshenyiwhich was worn in thepre-Qinperiod and became popular in the Han dynasty.[18]: 32

Thequjupaowas more luxurious than thezhijupaoas it required approximately 40% more materials than thezhijupao;and therefore the presence of more amount of wraps inqujupaoindicates that the robes are more increasingly more luxurious.[11]

Moreover, theshenyiin this period, regardless of its cut, could also be padded, lined, or unlined.[11]More examples of unearthed archeological artefacts ofshenyimade of diverse cuts and materials from theMawangduitomb can be found in Museums, such as thezhijusushadanyi(Chinese:Trực cư tố sa đan y;pinyin:zhíjūsùshādānyī;lit.'straight plain gauze unlined robe'), thequjusushadanyi(Chinese:Khúc cư tố sa đan y;lit.'curved plain gauze unlined robe'),[14]andsimianqujupao(Chinese:Ti miên khúc cư bào;lit.'silk cotton qujupao'),[29]found in theHunan Museum.According to theFangyanby Yang Xiong dating from theWestern Han dynasty,thedanyi(Chinese:Đan y;lit.'unlined clothing'), also calleddie(Chinese:褋),zuoyi(Chinese:Tá y), andchengyi(Chinese:Trình y) depending on its geographical location, was calledshenyiin ancient times.[30]

There were also gradual changes but clear distinctions in the form of theshenyibetween the early and late period of the Western Han dynasty.[12]In the early Western Han, some women wore body-huggingshenyiwhich was floor length with wide and long sleeves, long enough to cover the hand.[12]Others worequjupaowith a flowing extended panels which would create a tiered effects at the back.[12]

Moreover, the design of theshenyiwas closely related to the evolution of the Chinese trousers, especially theku.[17]A form ofzhijupao,known aschanoryu(Chinese:Du;pinyin:yú)[31]orchanyu(Chinese:Xiêm du;pinyin:chānyú), also became popular in the Han dynasty.[1]: 14 However, when thechanyufirst appeared, it was considered to be improper to use it as a ceremonial garment; it was also improper to use it outside of the house, and it was also improper to wear it at home when receiving guests.[1]: 14 The disrespectful nature of wearingchanyuat the court was even recorded in theShiji.[1]: 14 [32][33]Reasons why the wearing ofchanyuwas considered improper in those circumstances might be related to the wearing of the ancientku,which were trousers without crotches; and thus, this form ofzhijupaomight not have been sufficiently long to cover the body which was a disgraceful act from its wearer.[1]: 14 In the chapterJijiupian《 cấp tựu thiên 》byShi Youalso dating from the Western Han dynasty in theShuowen Jiezi,the set of attire calledzheku(Chinese:Điệp khố) consisted of a trousers calledzhekukun(Chinese:Điệp khố côn) which was covered by thechanyu(Chinese:Xiêm du),[34]thechanyuwas a short and tight knee-length robe instead of being long in length.[17]Akun(Chinese:Côn) was a form of Chinese trousers with crotches as opposed to theku.[17]

With time, when thekunbecame more popular, thezhijupao,which was shorter and easier to put on than thequjupao;thezhijupaothen started replacing thequjupaowhich had been long enough to cover theku.[18]: 32 Thekun,however, were only popular for some people of certain occupations, such as warriors, servants, and the lower class, in the Han dynasty and was not widely used by the general population as it was not easily accepted by the traditional etiquette of the Han culture.[17]Therefore, thekunwas never able to replace theku;moreover, the design of the ancientkuhad also evolved with time becoming long enough to cover the thighs, with some parts even covering the upper parts of the hips, such as theqiongkuwhich was especially designed for women in the Western Han dynasty court.[17]By the middle of the Western Han dynasty, thequjupaobecame nearly obsolete; and by the late Western Han dynasty, theshenyiwere straight rather than spiralled.[12]In theEastern Han dynasty,very few people woreshenyi.[27]

History of later development[edit]

Song dynasty[edit]

In theSong dynasty,Neo-Confucianphilosophies determined the conduct code of the scholars which then had a great influence on the lives of the people.[35]: 184 Zhu Xiand his Neo-Confucian colleagues developed a new cosmology, moral philosophy, and political principles based on intellectuals and elites sharing responsibility for the dynasty's management.[10]

The Neo-Confucians also re-constructed the meaning of theshenyi,restored, and re-invented it as the attire of the Neo-Confucian scholars in order to distinguish themselves from other scholars who came from school of thoughts.[10]Some Song dynasty scholars, such asSima GuangandZhu Xi,made their own version of the scholar gown based on theLiji,while other scholars such as Jin Lüxiang promoted it among his peers.[19]In hisZhuzi jiali《 chu tử gia lễ 》, Zhu Xi described the style of the long garment in considerable detail.[10]However, the shenyi used as a scholar gown was not popular in the Song dynasty and was even considered as "strange garment" despite some scholar-officials appreciated it.[10][19]Zhu Xi himself hesitated to wear it in public due to the social stigma which were associated to it; Zhu Xi was also accused for wearing strange garments by Shi Shengzu, who also accused Zhu Xi's followers of defying the social conventions.[10]Sima Guang, on the other hand, had the habit to wear the shenyi in private in his garden.[10]

According to philosopher and ancient scholar Lü Dalin (1044–91), noblemen and scholars used the shenyi for informality and ease, whereas commoners wore it as formal clothing. The garment was worn by court officials, noblemen and noblewomen, palace ladies, scholars and their wives, artisans, merchants, and farmers. It was the traditional informal attire of the ancient nobility. The robe became the formal clothing of commoners in the ancient Chinese world, reversing this reasoning. The Song Neo-Confucians praised the robe not only for its elegance and simplicity but also because it represented an essential political function.[10]In the Song dynasty, the shenyi was made with white fabric.[19]

Ming Dynasty[edit]

In theMing dynasty,in line with the attempt of theHongwu Emperorto replace all the foreign clothing used by the Mongols of Yuan, with the support of the Chinese elites who had supported the military campaigns against the Mongols. The Ming dynasty court thus gave many court commissions to the scholars who then helped enshrine Neo-Confucianism which was exemplified by Zhu Xi'sZhuzi jiali《 chu tử gia lễ 》as the orthodoxy of the Ming dynasty leading to the sudden rise in popularity of the Confucian shenyi.[10]This form of shenyi had suddenly become a popular form of robe for the scholars in 1368 and also became the official attire of the scholars.[10]Moreover, the shenyi had become a symbol of status and Han ethnicity as it was devoid of all foreign influence and also denoted Chinese intellectual pride and superiority.[10]

-

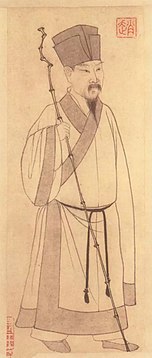

Ming man wearing shenyi

-

Ming man wearing shenyi

-

Ming dynasty man wearing shenyi

-

Ming dynasty Shenyi

Transition period between the Ming and Qing dynasties[edit]

The scholar robe's shenyi was a significant topic during the transition period between the Ming dynasty and the Qing dynasty. Huang Zongxi chose Huang Runyu's research version to serve as his contrast. According to Huang Zongxi's research, the scholar's robe shenyi represented the transfer of literati political values instead of dynastic politics and imperial orthodoxy. He said that the scholar's robe's style and function exactly matched the "great implication" (da yi) of literati values. Identifying the specific portion known as ren is the main distinction between these two versions. Ren was casually marked in the center of Huang Runyu's rendition and referred to the entire front piece, folding over the other side. The robe's expanded bottom, known as xuren, was fashionable throughout the Ming dynasty and can be seen in numerous Ming paintings.[10]

On the other hand, Huang Zongxi called ren the collar on the right folding to the left. This definition of ren is narrow and particular, referring to the collar that runs from the neck to the ground. The phrase xuren (continuing the ren) in Records of Rituals refers to the continuance of the collar. Xuren is no longer a name for a robe portion but rather a description of how ren is tailored, according to Huang Zongxi.[10]

Late 19th century to early 20th century[edit]

In the 19th century, some members of the gentry class still regarded the shenyi as a Chinese symbol and as having a proper status in society.[10]The Catholic missionaries in the 19th century who visited China perceived Chinese religions (being constituted of thesanjiao) as a degeneration of "true monotheism", widespread superstition, and idolatry while the Protestant missionaries perceived them as being religions with corrupted priesthood, mindless ritualism and idolatry in the Buddhist and Taoist worship.[36]The missionaries also viewed Christianity as being a higher civilizing force than Confucianism.[36]However, this view was not accepted by all the Chinese people, such as Kang Youwei and Cheng Huanzhang.[36]

Kang Youwei, who was an influential advocate of reforms in late Qing dynasty to theearly Republican period,[37]rejected the idea that Confucianism was defective when compared to Christianity. Kang Youwei thus wrote a controversial book in 1897, calledKongzi gaizhi kao《 khổng tử cải chế khảo 》(lit. 'Confucius the Reformer'), in which cited therufu( nho phục, lit. 'Confucian robe').[36]

Cheng Huanzhang, who was the founder of theConfucian Religion Association(Kongjiao hui khổng giáo hội )in 1912[37][38]and also established thezongsheng hui( tông thánh hội ) in Gaoyao in Guangdong,[36]aimed to bring advocates together for the restoration of Confucian texts to the educational curriculum and the official recognition of Confucianism as China's national religion.[37]Thus, in the written by Cheng Huanzhang also wrote theKongjiaolun,where he argued that therufuwas the clothing attire worn by the Confucianism religion priests.[39]He also listed 12 attributes which were associated with the religiosity of Confucianism: one of these attributes was aboutrufu,which according to him, was a specific form of attire consisting of the Confucian shenyi and a cap which had been designed by Confucius for his followers to wear.[38]However, despite the support of the prominent literati following the opening of theKongjiao hui,which had also become the most illustrious and influential organization of its time,[38]the parliament voted to not accord an official recognition to Confucianism as a ‘religion’ in both 1913 and 1916; the parliament gave official institutional status to five religions: Buddhism, Daoism, Catholicism, Protestantism, and Islam, and excluded Confucianism.[37]

21st century[edit]

Theshenyireappeared in the 21st century in China. The ancient-style shenyi in the form of both qujupao and the zhijupao reappeared and is worn by both men and women.[10]In 2003, a man named Wang Letian wore a DIYraojinshenyion the streets.[10]

-

Modern qujupao (left) and modern zhijupao (right) styled based on the designs of the ancient shenyi

-

A modern design of the qujupao calledxiao quju( tiểu khúc cư ), a shorter version of the qujupao shenyi

-

Processions of women wearing qujupao andxiao quju( tiểu khúc cư ), 2011

Types and styles[edit]

Qujupao-style[edit]

Standardqujupao[edit]

Thequjupaowas a robe which was long enough to cover the ankles of its wearer; it has an overlapping front lapel which closed on the right side in a style calledjiaoling youren;however, its right front piece was cut as a triangular front piece that crossed in front of the body and has rounded under hem.[1]: 13–14 [12]Thequjupaowould curve and wraps the dress to the back of its wearer[11]allowing the contrasting or decorative edging of the robe would create a spiralling effect when encircling the body.[12]The collar of thequjupaowas deliberately made in such ways to prevent any part of its wearer's body from being exposed.[18]: 16

- Various forms of the qujupao

-

Floor-trailing qujupao with narrow trim, large belt, and large and loose sleeves, Warring States Period

-

Floor-length qujupao with narrow decorative trim, Western Han dynasty

-

Floor-trailing qujupao with broad decorative trim, tomb ofHan Yang Ling,Western Han dynasty

-

Floor-length qujupao with broad decorative trim, tomb ofHan Yang Ling,Western Han dynasty

-

Unearthed quju shenyi

Raojinshenyi[edit]

Another version of thequjupaoisraojinshenyi(Chinese:Nhiễu khâm thâm y;lit.'winding lapel deep clothing'); this version of thequjupaocan typically be found in theMawangduitomb No.1 of the Western Han dynasty.[40]: 41–42 [41]: 16 Theraojinshenyiis characterized by overlapping curved front lapel which is elongated enough to spiral around the entire body.[40]: 41–42 It typically has a silk belt which is tied closely around the waist and hips to prevent the garment from loosening; the position of the belt depends on the length of the garment.[40]: 41 Theraojinshenyican have narrow sleeves or broad and loose sleeves.[40]: 41–42

- Forms of raojinshenyi

-

Raojinshenyiwith broad and loose sleeves, Western Han dynasty

-

Modern illustration of theRaojinshenyi(front view)

-

Raojinshenyiwith narrow sleeves,Mawangduitomb, Western Han dynasty

Zhijupao-style[edit]

Standardzhijupao[edit]

The front opening of thezhijupaowould fall straight down instead of having a curving front.[11]

- Various forms of zhijupao

-

Zhijusushadanyi with broad and loose straight sleeves, Mawangdui tomb, Western Han dynasty

-

Zhijupao, tomb of Han Yang Ling, Western Han dynasty

Confucian shenyi[edit]

Theshenyiin later dynasties directly descended from theshenyiworn in earlier dynasties Theshenyiwas originally made oframiecultivated in China. Ramie fabric needs to be bleached and produced 45 to 60 centimetre wide textile.[citation needed]

Similarly to theshenyiworn from Zhou to Han dynasties, the shenyi designed in Song dynasty followed the same principles. Theyi( y, blouse) andchang( thường, skirt) of the shenyi is sewn together.[19]The upper part is made up of 4 panels of ramie fabric, representing four seasons of a year. 2 panels are fold and sewn to cover the upper body. Another 2 panels of ramie fabric are sewn onto each side of the yi as two sleeves. The lower part is made up of 12 panels of fabric sewn together ( thập nhị phiến phùng hợp ), representing 12 months a year.[22]Its sleeves are wide with black cuff. It is also tied with a wide belt calleddadai( đại đái ) is tied in the front. According to the Japanese scholar Riken Nakai's shenyi template, there are four design features of the Shenyi dressing: upper and lower connections, square collar, length to the ankle, and additional coverage.[3]In theSong dynasty,the shenyi was made with white fabric.[19]

-

Illustration of dadai belt, from the Chinese encyclopediaGujin Tushu Jicheng,section "Ceremonial Usages"

Diyi[edit]

TheDiyiwas a set of attire which was worn as ceremonial clothing; a shenyi was also part of the diyi.

Influences and derivatives[edit]

Korea[edit]

InKorea,theshenyiis calledsimui(Korean:심의;Hanja:Thâm y).[6][42]It was introduced from China in the middle of Goryeo; however, the exact date of its introduction is unknown.[6]Thesimuiwas worn as an outer garment by theseonbi.[43]Theseonbiin Joseon imitated the clothing attire designed by Zhu Xi, i.e. theshenyiand the literati hat.[44]The seonbi, who valued thesimuigreatly, embraced it as a symbol of Confucian civilization, and continued to publish treatise on thesimuistarting from the sixteenth century AD.[10]Thesimuialso influenced other clothing, such as thecheollik,thenansam,andhakchangui.[6]

Thesimuiis white and in terms of design, it has wide sleeves and is composed on an upper and lower part which is attached together ( y thường liên y; Uisangyeonui) at the waistline; the lower part has 12 panels which represents 12 months.[42][43]It is a high-waist robe and a belt ( đại đái; dadae) is tied to thesimui.[42][43]There were also various forms ofsimuiwhich developed in the Joseon.[6][9]

-

Korean Confucian scholarSeo Jik-su

-

Korean Confucian scholarYun Jeung

-

Korean Confucian scholarYi Che-hyŏn

-

Korean Confucian scholarSong Si-yŏl

-

Korean Confucian scholarPark Ji-won

-

Korean Confucian scholarKwon Sang-ha

-

Korean Confucian scholarHeo Mok

-

Korean Confucian scholarKim Jong-jik

-

Korean Confucian scholarHan Seok-bong

Japan[edit]

The earlyTokugawa periodinJapan,some Japanese scholars, such asSeika FujiwaraandHayashi Razan,who self-proclaimed themselves as followers ofZhu Xiwore the Confucianshenyiand gave lectures in it.[10]

Seika Fujiwara, was usually perceived as the patriarch of theJapanese Neo-Confucianmovement during the Tokugawa period.[45]: 167 Seika used to be aBuddhistmonk before turning toConfucianism[46]: 104 and probably renounced Buddhism in the year 1594.[45]: 167

According to his biographer and follower, Hayashi Razan, Seika even appeared in front ofTokugawa Ieyasuin 1600 dressed in the Chinese-style Confucianshenyiandfujinwhich were prescribed for rituals by Zhu Xi;[45]: 171 this event also marked the beginning of the popularity of Confucianism in Japan.[46]: 104

Vietnam[edit]

In theLe dynasty,there were some ancient statues left behind, showing Confucian scholars wearing shenyi. But shenyi was not only worn by Confucian scholars; it was also commoners. Until theNguyen dynasty,shenyi was still seen in a number of photos.

Similar looking garments[edit]

See also[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^The 'shi' was a social stratum in ancient China which ranked just above the class of commoners, see Sheng, 1995. After the Spring and Autumn period, it became a term for scholars and intellectuals, see Zhang, 2015, pp. 257

- ^The early prescriptions refer to the rules and regulations which were previously established in the Liji

References[edit]

- ^abcdefghijklmnopqrHua, Mei (2011).Chinese Clothing.Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.ISBN9780521186896.OCLC1277432082.

- ^abLynch, Annette; Strauss, Mitchel D. (2014).Ethnic dress in the United States: a cultural encyclopedia.Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.ISBN9780759121508.Retrieved3 February2021.

- ^abcdefghijklmnopKuo, Y.-P.; Vongphantuset, J.; Joneurairatana, E. (November 16, 2021)."View of From Eastern inspiration to unisex fashion: a case study on traditional Chinese Shenyi attire".Silpakorn University, Thailand.RetrievedMarch 2,2022.

- ^Theobald, Ulrich (2013)."Zhuzi jiali chu tử gia lễ".www.chinaknowledge.de.Retrieved2022-06-23.

- ^abcZhao, Yin; Cai, Xinzhi (2014).Snapshots of Chinese Culture.Los Angeles: Bridge21 Publications.ISBN9781626430037.OCLC912499249.

- ^abcdefg"심의 ( thâm y )"[Simui].Encyclopedia of Korean Culture(in Korean).

- ^ab"Liji: Wang Zhi《 vương chế - Wang Zhi》".ctext.org(in Chinese (Taiwan)).Retrieved2022-06-23.

Hữu ngu thị hoàng nhi tế, thâm y nhi dưỡng lão. Hạ hậu thị thu nhi tế, yến y nhi dưỡng lão. Ân nhân hu nhi tế, cảo y nhi dưỡng lão. Chu nhân miện nhi tế, huyền y nhi dưỡng lão.

- ^Wang, Chen (2014-09-01)."Conservation study of Ming dynasty silk costumes excavated in Jiangsu region, China".Studies in Conservation.59(sup1): S177–S180.doi:10.1179/204705814X13975704319154.ISSN0039-3630.S2CID191384101.

- ^ab"심의 ( thâm y )"[Simui].Encyclopedia of Korean Folk Culture.Retrieved2022-03-20.

- ^abcdefghijklmnopqrsHu, Minghui (2016)."The Scholar's Robe: Material Culture and Political Power in Early Modern China".Frontiers of History in China.11(3): 339–375.doi:10.3868/s020-005-016-0020-4.ISSN1673-3401.

- ^abcdefghijklmnoSheng, Angela (1995)."The Disappearance of Silk Weaves with Weft Effects in Early China".Chinese Science(12): 41–76.ISSN0361-9001.JSTOR43290485.Retrieved3 February2021.

- ^abcdefghiLullo, Sheri A. (September 2019)."Trailing Locks and Flowing Robes: Dimensions of Beauty during China's Han dynasty (206 bc – ad 220)".Costume.53(2): 231–255.doi:10.3366/cost.2019.0122.S2CID204710548.Retrieved3 February2021.

- ^Ho, Wei; Lee, Eun-young (2009)."Modern Meaning of Han Chinese Clothing"(PDF).Journal of the Korea Fashion & Costume Design Association.11(1): 99–109.

- ^abcdeHunan Museum."Plain Gauze Gown".Hunan Museum.Retrieved3 February2021.

- ^Lüsted, Marcia Amidon (2017).Ancient Chinese daily life(1 ed.). New York: New York: Rosen Publishing. pp. 14–22.ISBN978-1-4777-8889-9.OCLC957525459.

- ^abZhang, Qizhi (2015). "The Rich and Colourful Social Life in Ancient China".An introduction to Chinese history and culture.China Academic Library. Heidelberg: Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. pp. 249–282.doi:10.1007/978-3-662-46482-3.ISBN978-3-662-46482-3.

- ^abcdefghijXu, Rui; Sparks, Diane (2011-01-01)."Symbolism and Evolution of Ku-form in Chinese Costume".Research Journal of Textile and Apparel.15(1): 11–21.doi:10.1108/RJTA-15-01-2011-B002.ISSN1560-6074.

- ^abcdefgZang, Yingchun; tang nghênh xuân. (2003).Zhongguo chuan tong fu shiTrung quốc truyện thống phục sức[Chinese traditional costumes and ornaments]. Lý trúc nhuận., vương đức hoa., cố ánh thần. (Di 1 ban ed.). Beijing: Wu zhou chuan bo chu ban she [ ngũ châu truyện bá xuất bản xã ].ISBN7-5085-0279-5.OCLC55895164.

- ^abcdefZhu, Ruixi; chu thụy hi (2016).A social history of middle-period China: the Song, Liao, Western Xia and Jin dynasties.Bangwei Zhang, Fusheng Liu, Chongbang Cai, Zengyu Wang, Peter Ditmanson, Bang Qian Zhu. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. p. 15.ISBN978-1-107-16786-5.OCLC953576345.

- ^Hunan20."Silk Painting with a Man Riding a Dragon Design of Warring States Period".Virtual collection of Asian Masterpieces (VCM).Retrieved2022-06-23.

{{cite web}}:CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^Hunan21."Silk Painting with a Lady, Phoenix and Dragon Designs of Warring States Period".Virtual collection of Asian Masterpieces (VCM).Retrieved2022-06-23.

{{cite web}}:CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^abcdefghi"Liji:《 thâm y - Shen Yi》".ctext.org.Translated by James Legge.Retrieved2021-02-07.

{{cite web}}:CS1 maint: others (link) - ^abcdefghiHsu, N. (August 31, 2021)."Dressing as a Sage: Clothing and Self-cultivation in Early Confucian Thought".Indiana University.RetrievedMarch 2,2022.

- ^"Liji: 《 ngọc tảo - Yu Zao》".ctext.org.Translated by James Legge.Retrieved2022-06-23.

{{cite web}}:CS1 maint: others (link) - ^David, Michael; Ing, Kaulana (2012).The Dysfunction of Ritual in Early Confucianism.Oxford University Press.ISBN9780199924905.OCLC865508152.

- ^abcFeng, Ge; Du, Zhenming (2015).Traditional Chinese Rites and Rituals.Cambridge Scholars Publishing.ISBN9781443887830.OCLC979864758.

- ^ab"Costume in the Han Dynasty".China Style.Archived fromthe originalon 7 July 2021.RetrievedMarch 2,2022.

- ^Hong Kong Heritage Museum."Images of Females in Chinese History: Thematic Gallery".Hong Kong Heritage Museum.Retrieved3 February2021.

- ^"'Xin Qi embroidery' floss-silk padded gown with lozenge pattern on brown silk gauze ".Hunan Museum.Retrieved2022-06-23.

- ^"Fang Yan:《 đệ tứ 》".ctext.org(in Chinese (Taiwan)).Retrieved2022-06-23.

- ^"Shuo Wen Jie Zi: 《 y bộ 》".ctext.org(in Chinese (Taiwan)).Retrieved2022-06-23.

- ^"Shiji:《 huệ cảnh nhàn hầu giả niên biểu 》".ctext.org(in Chinese (Taiwan)).Retrieved2022-06-23.

- ^"Shiji:《 ngụy kỳ võ an hầu liệt truyện 》".ctext.org(in Chinese (Taiwan)).Retrieved2022-06-23.

- ^"Ji Jiu Pian - điệp khố - Chinese Text Project".ctext.org(in Chinese (Taiwan)).Archivedfrom the original on 2022-06-16.Retrieved2022-06-18.

Xiêm du giáp phục điệp khố côn

- ^Xu, Guobin; Chen, Yanhui; Xu, Lianhua (2018), Xu, Guobin; Chen, Yanhui; Xu, Lianhua (eds.),"Clothing, Food, Housing and Transportation",Introduction to Chinese Culture: Cultural History, Arts, Festivals and Rituals,Singapore: Springer, pp. 181–203,doi:10.1007/978-981-10-8156-9_8,ISBN978-981-10-8156-9,retrieved2021-02-14

- ^abcdeLEONG, TAY WEI (2012-08-16).Saving the Chinese Nation and The World: Religion and Confucian Reformation, 1880s-1937(Thesis thesis).

- ^abcdeMurray, Julia K (2014-08-28)."A heavenly aura: Confucian modes of relic veneration".Journal of the British Academy.2.doi:10.5871/jba/002.059.

- ^abcdChen, Hsi-yüan (2013). "RELIGIONIZING CONFUCIANISM AND THE RE-ORIENTATION OF CONFUCIAN TRADITION IN MODERN CHINA". In Eggert, Marion; Hölscher, Lucian (eds.).Religion and Secularity: Transformations and Transfers of Religious Discourses in Europe and Asia.Brill. pp. 231–256.ISBN9789004251335.JSTOR10.1163/j.ctv2gjwv0k.17.

- ^Blanchon, Flora; Park-Barjot, Rang-Ri (2007).La nouvel age de Confucius: modern Confucianism in China and South Korea(in French). Paris: Presses Paris Sorbonne.ISBN9782840505020.OCLC963529613.

- ^abcdGao, Chunming (1987). Zhou, Xun (ed.).5000 Years of Chinese Costumes(English translation ed.). China Books & Periodicals.ISBN978-0835118224.OCLC762100301.

- ^Zhou, Xun (1984).Zhongguo fu shi wu qian nian《 trung quốc phục sức ngũ thiên niên 》[5000 Years Of Chinese Costumes] (in Chinese). Hong Kong: The Commercial Press.ISBN9789620750212.OCLC743416465.

- ^abcNam, Min-yi; Han, Myung-Sook (2000)."A Study on the Items and Shapes of Korean Shrouds".The International Journal of Costume Culture.3(2): 100–123.

- ^abcLee, Samuel Songhoon (2013).Hanbok: Timeless fashion tradition.Seoul: Seoul, Korea: Seoul Selection. pp. 58–59.ISBN978-89-97639-41-0.OCLC871061483.

- ^Yunesŭk'o Han'guk Wiwŏnhoe (2005).Korea Journal.Vol. 45. Korean National Commission for UNESCO. p. 125.

- ^abcMcCullen, James (2021). "Chapter 8 Confucian Spectacle in Edo Hayashi Razan and Cultural display".The Worship of Confucius in Japan.Brill.ISBN9781684175994.OCLC1290719734.

- ^abKöck, Stephan; Scheid, Bernhard; Pickl-Kolaczia, Brigitte (2021).Religion, Power, and the Rise of Shinto in Early Modern Japan.Bloomsbury Publishing.ISBN9781350181076.