Silent film

Asilent filmis afilmwithout synchronizedrecorded sound(or more generally, no audibledialogue). Though silent films conveynarrativeand emotion visually, various plot elements (such as a setting or era) or key lines of dialogue may, when necessary, be conveyed by the use of inter-title cards.

The term "silent film" is something of a misnomer, as these films were almost always accompanied by live sounds. During the silent era that existed from the mid-1890s to the late 1920s, apianist,theater organist—or even, in larger cities, anorchestra—would play music to accompany the films. Pianists and organists would play either fromsheet music,orimprovisation.Sometimes a person would even narrate the inter-title cards for the audience. Though at the time the technology to synchronize sound with the film did not exist, music was seen as an essential part of the viewing experience. "Silent film" is typically used as a historical term to describe an era of cinema prior to the invention of synchronized sound, but it also applies to such sound-era films asCity Lights,Modern TimesandSilent Moviewhich are accompanied by a music-only soundtrack in place of dialogue.

The termsilent filmis aretronym—a term created to retroactively distinguish something from later developments. Early sound films, starting withThe Jazz Singerin 1927, were variously referred to as the"talkies", "sound films", or "talking pictures".The idea of combining motion pictures with recorded sound is older than film (it was suggested almost immediately after Edison introduced thephonographin 1877), and some early experiments had the projectionist manually adjusting the frame rate to fit the sound,[1]but because of the technical challenges involved, the introduction of synchronized dialogue became practical only in the late1920swith the perfection of theAudion amplifier tubeand the advent of theVitaphonesystem.[2]Within a decade, the widespread production of silent films for popular entertainment had ceased, and the industry had moved fully into thesound era,in which movies were accompanied by synchronized sound recordings of spoken dialogue, music andsound effects.

Most early motion pictures are consideredlostowing to their physical decay, for thenitrate filmstockused in that era was extremely unstable and flammable. Additionally, many films were deliberately destroyed, because they had negligible remaining immediate financial value in that era. It has often been claimed that around 75 percent of silent films produced in the US have been lost, though these estimates are inaccurate due to a lack of numerical data.[3]

Elements and beginnings (1833–1894)

[edit]

Film projection mostly evolved frommagic lanternshows, in which images from handpainted glass slides were projected onto a wall or screen.[4]After the advent of photography in the 19th century, stillphotographswere sometimes used. Narration of the showman was important in spectacular entertainment screenings and vital in the lecturing circuit.[5]

The principle of stroboscopicanimationwas well-known since the introduction of thephenakistiscopein 1833, a popularoptical toy,but the development ofcinematographywas hampered by long exposure times forphotographic emulsions,untilEadweard Muybridgemanaged to record achronophotographicsequence in 1878. After others had animated his pictures inzoetropes,Muybridge started lecturing with his ownzoopraxiscopeanimation projector in 1880.

The work of other pioneering chronophotographers, includingÉtienne-Jules MareyandOttomar Anschütz,furthered the development of motion picture cameras, projectors and transparent celluloid film.

AlthoughThomas Edisonwas keen to develop a film system that would be synchronised with hisphonograph,he eventually introduced thekinetoscopeas a silent motion picture viewer in 1893 and later "kinetophone" versions remained unsuccessful.

Silent film era

[edit]The art of motion pictures grew into full maturity in the "silent era" (1894 in film–1929 in film). The height of the silent era (from the early1910s in filmto the late 1920s) was a particularly fruitful period, full of artistic innovation. The film movements ofClassical Hollywoodas well asFrench Impressionism,German Expressionism,andSoviet Montagebegan in this period. Silent filmmakers pioneered the art form to the extent that virtually every style and genre of film-making of the 20th and 21st centuries has its artistic roots in the silent era. The silent era was also a pioneering one from a technical point of view. Three-point lighting, theclose-up,long shot,panning,andcontinuity editingall became prevalent long before silent films were replaced by "talking pictures"or" talkies "in the late 1920s. Some scholars claim that the artistic quality of cinema decreased for several years, during the early 1930s, untilfilm directors,actors, and production staff adapted fully to the new "talkies" around the mid-1930s.[6]

The visual quality of silent movies—especially those produced in the 1920s—was often high, but there remains a widely held misconception that these films were primitive, or are barely watchable by modern standards.[7]This misconception comes from the general public's unfamiliarity with the medium, as well as from carelessness on the part of the industry. Most silent films are poorly preserved, leading to their deterioration, and well-preserved films are often played back at the wrong speed or suffer fromcensorship cutsand missing frames and scenes, giving the appearance of poor editing.[8][9]Many silent films exist only in second- or third-generation copies, often made from already damaged and neglected film stock.[6]Another widely held misconception is that silent films lacked color. In fact, color was far more prevalent in silent films than in the first few decades of sound films. By the early 1920s, 80 percent of movies could be seen in some sort of color, usually in the form offilm tintingortoningor even hand coloring, but also with fairly natural two-color processes such asKinemacolorandTechnicolor.[10]Traditional colorization processes ceased with the adoption ofsound-on-filmtechnology. Traditional film colorization, all of which involved the use of dyes in some form, interfered with the high resolution required for built-in recorded sound, and were therefore abandoned. The innovative three-strip technicolor process introduced in the mid-1930s was costly and fraught with limitations, and color would not have the same prevalence in film as it did in the silents for nearly four decades.

Inter-titles

[edit]

As motion pictures gradually increased in running time, a replacement was needed for the in-house interpreter who would explain parts of the film to the audience. Because silent films had no synchronized sound for dialogue, onscreeninter-titleswere used to narrate story points, present key dialogue and sometimes even comment on the action for the audience. Thetitle writerbecame a key professional in silent film and was often separate from thescenario writerwho created the story. Inter-titles (ortitlesas they were generally called at the time) "often were graphic elements themselves, featuring illustrations or abstract decorations that commented on the action".[11][12][citation needed]

Live music and other sound accompaniment

[edit]Showings of silent films almost always featured live music starting with the first public projection of movies by the Lumière brothers on December 28, 1895, in Paris. This was furthered in 1896 by the first motion-picture exhibition in the United States atKoster and Bial's Music Hallin New York City. At this event, Edison set the precedent that all exhibitions should be accompanied by an orchestra.[13]From the beginning, music was recognized as essential, contributing atmosphere, and giving the audience vital emotional cues. Musicians sometimes played on film sets during shooting for similar reasons. However, depending on the size of the exhibition site, musical accompaniment could drastically change in scale.[4]Small-town and neighborhood movie theatres usually had apianist.Beginning in the mid-1910s, large city theaters tended to haveorganistsor ensembles of musicians. Massivetheatre organs,which were designed to fill a gap between a simple piano soloist and a larger orchestra, had a wide range of special effects. Theatrical organs such as the famous "Mighty Wurlitzer"could simulate some orchestral sounds along with a number of percussion effects such as bass drums and cymbals, andsound effectsranging from "train and boat whistles [to] car horns and bird whistles;... some could even simulate pistol shots, ringing phones, the sound of surf, horses' hooves, smashing pottery, [and] thunder and rain".[14]

Musical scoresfor early silent films were eitherimprovisedor compiled of classical or theatrical repertory music. Once full features became commonplace, however, music was compiled fromphotoplay musicby the pianist, organist, orchestra conductor or themovie studioitself, which included a cue sheet with the film. These sheets were often lengthy, with detailed notes about effects and moods to watch for. Starting with the mostly original score composed byJoseph Carl BreilforD. W. Griffith's epicThe Birth of a Nation(1915), it became relatively common for the biggest-budgeted films to arrive at the exhibiting theater with original, specially composed scores.[15]However, the first designated full-blown scores had in fact been composed in 1908, byCamille Saint-SaënsforThe Assassination of the Duke of Guise,[16]and byMikhail Ippolitov-IvanovforStenka Razin.

When organists or pianists used sheet music, they still might add improvisational flourishes to heighten the drama on screen. Even when special effects were not indicated in the score, if an organist was playing a theater organ capable of an unusual sound effect such as "galloping horses", it would be used during scenes of dramatic horseback chases.

At the height of the silent era, movies were the single largest source of employment for instrumental musicians, at least in the United States. However, the introduction of talkies, coupled with the roughly simultaneous onset of theGreat Depression,was devastating to many musicians.

A number of countries devised other ways of bringing sound to silent films. The earlycinema of Brazil,for example, featuredfitas cantatas(singing films), filmedoperettaswith singers performing behind the screen.[17]InJapan,films had not only live music but also thebenshi,a live narrator who provided commentary and character voices. Thebenshibecame a central element in Japanese film, as well as providing translation for foreign (mostly American) movies.[18]The popularity of thebenshiwas one reason why silent films persisted well into the 1930s in Japan. Conversely, asbenshi-narrated films often lacked intertitles, modern-day audiences may sometimes find it difficult to follow the plots without specialised subtitling or additional commentary.

Score restorations from 1980 to the present

[edit]Few film scores survived intact from the silent period, andmusicologistsare still confronted by questions when they attempt to precisely reconstruct those that remain. Scores used in current reissues or screenings of silent films may be complete reconstructions of compositions, newly composed for the occasion, assembled from already existing music libraries, or improvised on the spot in the manner of the silent-era theater musician.

Interest in the scoring of silent films fell somewhat out of fashion during the 1960s and 1970s. There was a belief in many college film programs andrepertory cinemasthat audiences should experience silent film as a pure visual medium, undistracted by music. This belief may have been encouraged by the poor quality of the music tracks found on many silent film reprints of the time. Since around 1980, there has been a revival of interest in presenting silent films with quality musical scores (either reworkings of period scores or cue sheets, or the composition of appropriate original scores). An early effort of this kind wasKevin Brownlow's 1980 restoration ofAbel Gance'sNapoléon(1927), featuring a score byCarl Davis.A slightly re-edited and sped-up version of Brownlow's restoration was later distributed in the United States byFrancis Ford Coppola,with a live orchestral score composed by his fatherCarmine Coppola.

In 1984, an edited restoration ofMetropolis(1927) was released with a new rock music score by producer-composerGiorgio Moroder.Although the contemporary score, which included pop songs byFreddie Mercury,Pat Benatar,andJon AndersonofYes,was controversial, the door had been opened for a new approach to the presentation of classic silent films.

Today, a large number of soloists, music ensembles, and orchestras perform traditional and contemporary scores for silent films internationally.[19]The legendary theater organistGaylord Cartercontinued to perform and record his original silent film scores until shortly before his death in 2000; some of those scores are available on DVD reissues. Other purveyors of the traditional approach include organists such asDennis Jamesand pianists such asNeil Brand,Günter Buchwald, Philip C. Carli,Ben Model,andWilliam P. Perry.Other contemporary pianists, such as Stephen Horne and Gabriel Thibaudeau, have often taken a more modern approach to scoring.

Orchestral conductors such as Carl Davis andRobert Israelhave written and compiled scores for numerous silent films; many of these have been featured in showings onTurner Classic Moviesor have been released on DVD. Davis has composed new scores for classic silent dramas such asThe Big Parade(1925) andFlesh and the Devil(1927). Israel has worked mainly in silent comedy, scoring the films ofHarold Lloyd,Buster Keaton,Charley Chase,and others.Timothy Brockhas restored many ofCharlie Chaplin's scores, in addition to composing new scores.

Contemporary music ensembles are helping to introduce classic silent films to a wider audience through a broad range of musical styles and approaches. Some performers create new compositions using traditional musical instruments, while others add electronic sounds, modern harmonies, rhythms, improvisation, and sound design elements to enhance the viewing experience. Among the contemporary ensembles in this category areUn Drame Musical Instantané,Alloy Orchestra,Club Foot Orchestra,Silent Orchestra,Mont Alto Motion Picture Orchestra, Minima and the Caspervek Trio,RPM Orchestra.Donald Sosin and his wife Joanna Seaton specialize in adding vocals to silent films, particularly where there is onscreen singing that benefits from hearing the actual song being performed. Films in this category include Griffith'sLady of the PavementswithLupe Vélez,Edwin Carewe'sEvangelinewithDolores del Río,andRupert Julian'sThe Phantom of the OperawithMary PhilbinandVirginia Pearson.[citation needed]

The Silent Film Sound and Music Archive digitizes music and cue sheets written for silent films and makes them available for use by performers, scholars, and enthusiasts.[20]

Acting techniques

[edit]

Silent-film actors emphasizedbody languageandfacial expressionso that theaudiencecould better understand what an actor was feeling and portraying on screen. Much silent film acting is apt to strike modern-day audiences as simplistic orcampy.The melodramatic acting style was in some cases a habit actors transferred from their former stage experience.Vaudevillewas an especially popular origin for many American silent film actors.[4]The pervading presence of stage actors in film was the cause of this outburst from directorMarshall Neilanin 1917: "The sooner the stage people who have come into pictures get out, the better for the pictures." In other cases, directors such asJohn Griffith Wrayrequired their actors to deliver larger-than-life expressions for emphasis. As early as 1914, American viewers had begun to make known their preference for greater naturalness on screen.[21]

Silent films became less vaudevillian in the mid-1910s, as the differences between stage and screen became apparent. Due to the work of directors such asD. W. Griffith,cinematography became less stage-like, and the development of theclose upallowed for understated and realistic acting.Lillian Gishhas been called film's "first true actress" for her work in the period, as she pioneered new film performing techniques, recognizing the crucial differences between stage and screen acting. Directors such asAlbert CapellaniandMaurice Tourneurbegan to insist on naturalism in their films. By the mid-1920s many American silent films had adopted a more naturalistic acting style, though not all actors and directors accepted naturalistic, low-key acting straight away; as late as 1927, films featuring expressionistic acting styles, such asMetropolis,were still being released.[21]Greta Garbo,whose first American film was released in 1926, would become known for her naturalistic acting.

According to Anton Kaes, a silent film scholar from the University of California, Berkeley, American silent cinema began to see a shift in acting techniques between 1913 and 1921, influenced by techniques found in German silent film. This is mainly attributed to the influx of emigrants from theWeimar Republic,"including film directors, producers, cameramen, lighting and stage technicians, as well as actors and actresses".[23]

Projection speed

[edit]Until the standardization of the projection speed of 24 frames per second (fps) for sound films between 1926 and 1930, silent films were shot at variable speeds (or "frame rates") anywhere from 12 to 40 fps, depending on the year and studio.[24]"Standard silent film speed" is often said to be 16 fps as a result of theLumière brothers'Cinématographe,but industry practice varied considerably; there was no actual standard.William Kennedy Laury Dickson,an Edison employee, settled on the astonishingly fast 40 frames per second.[4]Additionally, cameramen of the era insisted that their cranking technique was exactly 16 fps, but modern examination of the films shows this to be in error, and that they often cranked faster. Unless carefully shown at their intended speeds silent films can appear unnaturally fast or slow. However, some scenes were intentionallyundercrankedduring shooting to accelerate the action—particularly for comedies and action films.[24]

Slow projection of acellulose nitratebase film carried a risk of fire, as each frame was exposed for a longer time to the intense heat of the projection lamp; but there were other reasons to project a film at a greater pace. Often projectionists received general instructions from the distributors on the musical director's cue sheet as to how fast particular reels or scenes should be projected.[24]In rare instances, usually for larger productions, cue sheets produced specifically for the projectionist provided a detailed guide to presenting the film. Theaters also—to maximize profit—sometimes varied projection speeds depending on the time of day or popularity of a film,[25]or to fit a film into a prescribed time slot.[24]

All motion-picture film projectors require a moving shutter to block the light whilst the film is moving, otherwise the image is smeared in the direction of the movement. However this shutter causes the image toflicker,and images with low rates of flicker are very unpleasant to watch. Early studies byThomas Edisonfor hisKinetoscopemachine determined that any rate below 46 images per second "will strain the eye".[24]and this holds true for projected images under normal cinema conditions also. The solution adopted for the Kinetoscope was to run the film at over 40 frames/sec, but this was expensive for film. However, by using projectors with dual- and triple-blade shutters the flicker rate is multiplied two or three times higher than the number of film frames — each frame being flashed two or three times on screen. A three-blade shutter projecting a 16 fps film will slightly surpass Edison's figure, giving the audience 48 images per second. During the silent era projectors were commonly fitted with 3-bladed shutters. Since the introduction of sound with its 24 frame/sec standard speed 2-bladed shutters have become the norm for 35 mm cinema projectors, though three-bladed shutters have remained standard on 16 mm and 8 mm projectors, which are frequently used to project amateur footage shot at 16 or 18 frames/sec. A 35 mm film frame rate of 24 fps translates to a film speed of 456 millimetres (18.0 in) per second.[26]One 1,000-foot (300 m) reel requires 11 minutes and 7 seconds to be projected at 24 fps, while a 16 fps projection of the same reel would take 16 minutes and 40 seconds, or 304 millimetres (12.0 in) per second.[24]

In the 1950s, manytelecineconversions of silent films at grossly incorrect frame rates for broadcast television may have alienated viewers.[27]Film speed is often a vexed issue among scholars and film buffs in the presentation of silents today, especially when it comes to DVD releases ofrestored films,such as the case of the 2002 restoration ofMetropolis.[28]

Tinting

[edit]

With the lack of natural color processing available, films of the silent era were frequently dipped indyestuffsand dyed various shades and hues to signal a mood or represent a time of day. Hand tinting dates back to 1895 in the United States with Edison's release of selected hand-tinted prints ofButterfly Dance.Additionally, experiments in color film started as early as in 1909, although it took a much longer time for color to be adopted by the industry and an effective process to be developed.[4]Blue represented night scenes, yellow or amber meant day. Red represented fire and green represented a mysterious atmosphere. Similarly, toning of film (such as the common silent film generalization ofsepia-toning) with special solutions replaced the silver particles in the film stock with salts or dyes of various colors. A combination of tinting and toning could be used as an effect that could be striking.

Some films were hand-tinted, such asAnnabelle Serpentine Dance(1894), fromEdison Studios.In it,Annabelle Whitford,[29]a young dancer from Broadway, is dressed in white veils that appear to change colors as she dances. This technique was designed to capture the effect of the live performances ofLoie Fuller,beginning in 1891, in which stage lights with colored gels turned her white flowing dresses and sleeves into artistic movement.[30]Hand coloring was often used in the early "trick" and fantasy films of Europe, especially those byGeorges Méliès.Méliès began hand-tinting his work as early as 1897 and the 1899Cendrillion(Cinderella) and 1900Jeanne d'Arc(Joan of Arc) provide early examples of hand-tinted films in which the color was a critical part of the scenography ormise-en-scène;such precise tinting used the workshop ofElisabeth Thuillierin Paris, with teams of female artists adding layers of color to each frame by hand rather than using a more common (and less expensive) process of stenciling.[31]A newly restored version of Méliès'A Trip to the Moon,originally released in 1902, shows an exuberant use of color designed to add texture and interest to the image.[32]

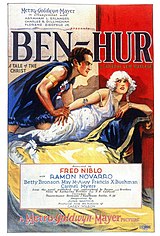

Comments by an American distributor in a 1908 film-supply catalog further underscore France's continuing dominance in the field of hand-coloring films during the early silent era. The distributor offers for sale at varying prices "High-Class" motion pictures byPathé,Urban-Eclipse,Gaumont,Kalem,Itala Film,Ambrosio Film,andSelig.Several of the longer, more prestigious films in the catalog are offered in both standard black-and-white "plain stock" as well as in "hand-painted" color.[33]A plain-stock copy, for example, of the 1907 releaseBen Huris offered for $120 ($4,069 USD today), while a colored version of the same 1000-foot, 15-minute film costs $270 ($9,156) including the extra $150 coloring charge, which amounted to 15 cents more per foot.[33]Although the reasons for the cited extra charge were likely obvious to customers, the distributor explains why his catalog's colored films command such significantly higher prices and require more time for delivery. His explanation also provides insight into the general state of film-coloring services in the United States by 1908:

The coloring of moving picture films is a line of work which cannot be satisfactorily performed in the United States. In view of the enormous amount of labor involved which calls for individual hand painting of every one of sixteen pictures to the foot or 16,000 separate pictures for each 1,000 feet of film very few American colorists will undertake the work at any price.

As film coloring has progressed much more rapidly in France than in any other country, all of our coloring is done for us by the best coloring establishment in Paris and we have found that we obtain better quality, cheaper prices and quicker deliveries, even in coloring American made films, than if the work were done elsewhere.[33]

By the beginning of the 1910s, with the onset of feature-length films, tinting was used as another mood setter, just as commonplace as music. The directorD. W. Griffithdisplayed a constant interest and concern about color, and used tinting as a special effect in many of his films. His 1915 epicThe Birth of a Nationused a number of colors, including amber, blue, lavender, and a striking red tint for scenes such as the "burning of Atlanta" and the ride of theKu Klux Klanat the climax of the picture. Griffith later invented a color system in which colored lights flashed on areas of the screen to achieve a color.

With the development of sound-on-film technology and the industry's acceptance of it, tinting was abandoned altogether, because the dyes used in the tinting process interfered with the soundtracks present on film strips.[4]

Early studios

[edit]The early studios were located in theNew York City area.Edison Studios were first inWest Orange, New Jersey(1892), they were moved tothe Bronx, New York(1907). Fox (1909) and Biograph (1906) started inManhattan,with studios in St George,Staten Island.Other films were shot inFort Lee, New Jersey.In December 1908, Edison led the formation of theMotion Picture Patents Companyin an attempt to control the industry and shut out smaller producers. The "Edison Trust", as it was nicknamed, was made up ofEdison,Biograph,Essanay Studios,Kalem Company,George Kleine Productions,Lubin Studios,Georges Méliès,Pathé,Selig Studios,andVitagraph Studios,and dominated distribution through theGeneral Film Company.This company dominated the industry as both a vertical and horizontalmonopolyand is a contributing factor in studios' migration to the West Coast. The Motion Picture Patents Co. and the General Film Co. were found guilty ofantitrustviolation in October 1915, and were dissolved.

TheThanhouserfilm studio was founded inNew Rochelle, New York,in 1909 by American theatrical impresarioEdwin Thanhouser.The company produced and released 1,086 films between 1910 and 1917, including the firstfilm serial,The Million Dollar Mystery,released in 1914.[34]The firstwesternswere filmed atFred Scott's Movie Ranch in South Beach, Staten Island. Actors costumed ascowboysand Native Americans galloped across Scott's movie ranch set, which had a frontier main street, a wide selection of stagecoaches and a 56-foot stockade. The island provided a serviceable stand-in for locations as varied as the Sahara desert and a British cricket pitch.War sceneswere shot on the plains ofGrasmere, Staten Island.The Perils of Paulineand its even more popular sequelThe Exploits of Elainewere filmed largely on the island. So was the 1906 blockbusterLife of a Cowboy,byEdwin S. Porter Company,and filming moved to the West Coast around 1912.

Top-grossing silent films in the United States

[edit]The following are American films from the silent film era that had earned the highest gross income as of 1932. The amounts given aregross rentals(the distributor's share of the box-office) as opposed to exhibition gross.[35]

| Title | Year | Director(s) | Gross rental |

|---|---|---|---|

| The Birth of a Nation | 1915 | D. W. Griffith | $10,000,000 |

| The Big Parade | 1925 | King Vidor | $6,400,000 |

| Ben-Hur | 1925 | Fred Niblo | $5,500,000 |

| The Kid | 1921 | Charlie Chaplin | $5,450,000 |

| Way Down East | 1920 | D. W. Griffith | $5,000,000 |

| City Lights | 1931 | Charlie Chaplin | $4,300,000 |

| The Gold Rush | 1925 | Charlie Chaplin | $4,250,000 |

| The Circus | 1928 | Charlie Chaplin | $3,800,000 |

| The Covered Wagon | 1923 | James Cruze | $3,800,000 |

| The Hunchback of Notre Dame | 1923 | Wallace Worsley | $3,500,000 |

| The Ten Commandments | 1923 | Cecil B. DeMille | $3,400,000 |

| Orphans of the Storm | 1921 | D. W. Griffith | $3,000,000 |

| For Heaven's Sake | 1926 | Sam Taylor | $2,600,000 |

| The Road to Ruin | 1928 | Norton S. Parker | $2,500,000 |

| 7th Heaven | 1928 | Frank Borzage | $2,500,000 |

| What Price Glory? | 1926 | Raoul Walsh | $2,400,000 |

| Abie's Irish Rose | 1928 | Victor Fleming | $1,500,000 |

During the sound era

[edit]Transition

[edit]Although attempts to create sync-sound motion pictures go back to the Edison lab in 1896, only from the early 1920s were the basic technologies such asvacuum tubeamplifiers and high-quality loudspeakers available. The next few years saw a race to design, implement, and market several rivalsound-on-discandsound-on-filmsound formats, such asPhotokinema(1921),Phonofilm(1923),Vitaphone(1926),Fox Movietone(1927) andRCA Photophone(1928).

Warner Bros.was the first studio to accept sound as an element in film production and utilize the Vitaphone, a sound-on-disc technology, to do so.[4]The studio then releasedThe Jazz Singerin 1927, which marked the first commercially successfulsound film,but silent films were still the majority of features released in both 1927 and 1928, along with so-calledgoat-glandedfilms: silents with a subsection of sound film inserted. Thus the modern sound film era may be regarded as coming to dominance beginning in 1929.

For a listing of notable silent era films, seeList of years in filmfor the years between the beginning of film and 1928. The following list includes only films produced in the sound era with the specific artistic intention of being silent.

- City Girl,F. W. Murnau,1930

- Earth,Aleksandr Dovzhenko,1930

- The Silent Enemy,H.P. Carver, 1930[36][37]

- Borderline,Kenneth Macpherson,1930

- City Lights,Charlie Chaplin,1931

- Tabu,F. W. Murnau, 1931

- I Was Born, But...,Yasujirō Ozu,1932

- Passing Fancy,Yasujirō Ozu, 1933

- The Goddess,Wu Yonggang,1934

- A Story of Floating Weeds,Yasujirō Ozu, 1934

- The Downfall of Osen,Kenji Mizoguchi,1935

- Legong,Henri de la Falaise,1935

- An Inn in Tokyo,Yasujirō Ozu, 1935

- Happiness,Aleksandr Medvedkin,1935

- Cosmic Voyage,Vasili Zhuravlov, 1936

Later homages

[edit]Several filmmakers have paid homage to the comedies of the silent era, includingCharlie Chaplin,withModern Times(1936),Orson WelleswithToo Much Johnson(1938),Jacques TatiwithLes Vacances de Monsieur Hulot(1953),Pierre EtaixwithThe Suitor(1962), andMel BrookswithSilent Movie(1976). Taiwanese directorHou Hsiao-hsien's acclaimed dramaThree Times(2005) is silent during its middle third, complete with intertitles;Stanley Tucci'sThe Impostorshas an opening silent sequence in the style of early silent comedies. Brazilian filmmaker Renato Falcão'sMargarette's Feast(2003) is silent. Writer/director Michael Pleckaitis puts his own twist on the genre withSilent(2007). While not silent, theMr. Beantelevision series and movies have used the title character's non-talkative nature to create a similar style of humor. A lesser-known example isJérôme Savary'sLa fille du garde-barrière(1975), an homage to silent-era films that uses intertitles and blends comedy, drama, and explicit sex scenes (which led to it being refused a cinema certificate by theBritish Board of Film Classification).

In 1990,Charles Lanedirected and starred inSidewalk Stories,a low budget salute to sentimental silent comedies, particularlyCharlie Chaplin'sThe Kid.

The German filmTuvalu(1999) is mostly silent; the small amount of dialog is an odd mix of European languages, increasing the film's universality.Guy Maddinwon awards for his homage to Soviet-era silent films with his shortThe Heart of the Worldafter which he made a feature-length silent,Brand Upon the Brain!(2006), incorporating liveFoley artists,narration and orchestra at select showings.Shadow of the Vampire(2000) is a highly fictionalized depiction of the filming ofFriedrich Wilhelm Murnau's classic silentvampiremovieNosferatu(1922).Werner Herzoghonored the same film in his own version,Nosferatu: Phantom der Nacht(1979).

Some films draw a direct contrast between the silent film era and the era of talkies.Sunset Boulevardshows the disconnect between the two eras in the character ofNorma Desmond,played by silent film starGloria Swanson,andSingin' in the Raindeals withHollywoodartists adjusting to the talkies.Peter Bogdanovich's 1976 filmNickelodeondeals with the turmoil of silent filmmaking in Hollywood during the early 1910s, leading up to the release ofD. W. Griffith's epicThe Birth of a Nation(1915).

In 1999, theFinnishfilmmakerAki KaurismäkiproducedJuhain black and white, which captures the style of a silent film, using intertitles in place of spoken dialogue. Specialrelease printswith titles in several different languages were produced for international distribution.[38]In India, the filmPushpak(1988),[39]starringKamal Haasan,was a black comedy entirely devoid of dialog. The Australian filmDoctor Plonk(2007), was a silent comedy directed byRolf de Heer.Stage plays have drawn upon silent film styles and sources. Actor/writersBilly Van ZandtandJane Milmorestaged their Off-Broadway slapstick comedySilent Laughteras a live action tribute to the silent screen era.[40]Geoff Sobelle and Trey Lyford created and starred inAll Wear Bowlers(2004), which started as an homage toLaurel and Hardythen evolved to incorporate life-sized silent film sequences of Sobelle and Lyford who jump back and forth between live action and the silver screen.[41]The animated filmFantasia(1940), which is eight different animation sequences set to music, can be considered a silent film, with only one short scene involving dialogue. The espionage filmThe Thief(1952) has music and sound effects, but no dialogue, as doThierry Zéno's 1974Vase de NocesandPatrick Bokanowski's 1982The Angel.

In 2005, theH. P. Lovecraft Historical Societyproduced asilent film versionof Lovecraft's storyThe Call of Cthulhu.This film maintained a period-accurate filming style, and was received as both "the best HPL adaptation to date" and, referring to the decision to make it as a silent movie, "a brilliant conceit".[42]

The French filmThe Artist(2011), written and directed byMichel Hazanavicius,plays as a silent film and is set in Hollywood during the silent era. It also includes segments of fictitious silent films starring its protagonists. It won theAcademy Award for Best Picture.[43]

The Japanesevampire filmSanguivorous(2011) is not only done in the style of a silent film, but even toured with live orchestral accompaniment.[44][45]Eugene Chadbournehas been among those who have played live music for the film.[46]

Blancanievesis a 2012 Spanish black-and-white silent fantasy drama film written and directed byPablo Berger.[47]

The American feature-length silent filmSilent Life,which started in 2006 and features performances byIsabella RosselliniandGalina Jovovich,mother ofMilla Jovovich,premiered in 2013. The film is based on the life of silent screen iconRudolph Valentino,known as Hollywood's first "Great Lover". After emergency surgery, Valentino loses his grip on reality and begins to see the recollection of his life in Hollywood from a perspective of a coma – as a silent film shown at a movie palace, the magical portal between life and eternity, between reality and illusion.[48][49]

The Picnicis a 2012 short film made in the style of two-reel silent melodramas and comedies. It was part of the exhibit,No Spectators: The Art of Burning Man,a 2018–2019 exhibit curated by theRenwick Galleryof theSmithsonian American Art Museum.[50]The film was shown inside a miniature 12-seatArt Decomovie palace on wheels calledThe Capitol Theater,created by Oakland, Ca. art collectiveFive Ton Crane.

Right Thereis a 2013 short film that is an homage to silent film comedies.

The 2015 British animated filmShaun the Sheep Movie,based onShaun the Sheep,was released to positive reviews and was a box office success.Aardman Animationsalso producedMorphandTimmy Time,as well as many other silent short films.

TheAmerican Theatre Organ Societypays homage to the music of silent films, as well as thetheatre organsthat played such music. With over 75 local chapters, the organization seeks to preserve and promote theater organs and music as an art form.[51]

TheGlobe International Silent Film Festival(GISFF) is an annual event focusing on image and atmosphere in cinema which takes place in a reputable university or academic environment every year and is a platform for showcasing and judging films from filmmakers who are active in this field.[52]In 2018, film director Christopher Annino shot the now internationally award-winning feature silent filmSilent Times.[53][54][55]The film pays homage to many of the characters from the 1920s, including Officer Keystone, played by David Blair; Enzio Marchello who portrays a Charlie Chaplin character.Silent Timeswon best silent film at the Oniros Film Festival. Set in a small New England town, the story centers on Oliver Henry III (played by Westerly native Geoff Blanchette), a small-time crook turned vaudeville theater owner. From humble beginnings in England, he immigrates to the US in search of happiness and fast cash. He becomes acquainted with people from all walks of life, from burlesque performers, mimes, hobos to classy flapper girls, as his fortunes rise and his life spins ever more out of control.

Preservation and lost films

[edit]

The vast majority of the silent films produced in the late 19th and early 20th centuries are considered lost. According to a September 2013 report published by the United StatesLibrary of Congress,some 70 percent of American silent feature films fall into this category.[56]There are numerous reasons for this number being so high. Some films have been lost unintentionally, but most silent films were destroyed on purpose. Between the end of the silent era and the rise ofhome video,film studios would often discard large numbers of silent films out of a desire to free up storage in their archives, assuming that they had lost the cultural relevance and economic value to justify the amount of space they occupied. Additionally, due to the fragile nature of thenitrate film stockwhich was used to shoot and distribute silent films, many motion pictures have irretrievably deteriorated or have been lost in accidents, including fires (because nitrate is highly flammable and can spontaneously combust when stored improperly). Examples of such incidents include the1965 MGM vault fireand the1937 Fox vault fire,both of which caused catastrophic losses of films. Many such films not completely destroyed survive only partially, or in badly damaged prints. Some lost films, such asLondon After Midnight(1927), lost in the MGM fire, have been the subject of considerable interest byfilm collectors and historians.

Major silent films presumed lost include:

- The Fairylogue and Radio-Plays(1908)

- Saved from the Titanic(1912), which featured survivors of the disaster;[57]

- The Life of General Villa,starringPancho Villahimself

- The Apostle,the firstanimated feature film(1917)

- Cleopatra(1917)[58]

- Kiss Me Again(1925)

- Arirang(1926)

- The Great Gatsby(1926)

- London After Midnight(1927)

- The Patriot(1928), the only lostBest Picturenominee; only thetrailersurvives

- Gentlemen Prefer Blondes(1928)[59]

Though most lost silent films will never be recovered,some have been discoveredin film archives or private collections. Discovered and preserved versions may be editions made for the home rental market of the 1920s and 1930s that are discovered in estate sales, etc.[60]The degradation of old film stock can be slowed through proper archiving, and films can be transferred tosafety film stockor to digital media for preservation. Thepreservationof silent films has been a high priority for historians and archivists.[61]

Dawson Film Find

[edit]Dawson City,in theYukonterritory of Canada, was once the end of the distribution line for many films. In 1978, a cache of more than 500 reels of nitrate film was discovered during the excavation of a vacant lot formerly the site of the Dawson Amateur Athletic Association, which had started showing films at its recreation center in 1903.[61][62]Works byPearl White,Helen Holmes,Grace Cunard,Lois Weber,Harold Lloyd,Douglas Fairbanks,andLon Chaney,among others, were included, as well as many newsreels. The titles were stored at the local library until 1929 when the flammable nitrate was used as landfill in a condemned swimming pool. Having spent 50 years under the permafrost of the Yukon, the reels turned out to be extremely well preserved. Owing to its dangerous chemical volatility,[63]the historical find was moved by military transport toLibrary and Archives Canadaand the USLibrary of Congressfor storage (and transfer tosafety film). A documentary about the find,Dawson City: Frozen Time,was released in 2016.[64][65]

Film festivals

[edit]There are annual silent film festivals around the globe.[66]

- Capitolfest, at theCapitol TheatreinRome, New York.[67]

- Kansas Silent Film Festival, at theKansas City Music HallinKansas City, Missouri.[68]

- San Francisco Silent Film Festival, at theCastro TheatreinSan Francisco, California.[69]

- Toronto Silent Film Festival, at theFox TheatreinToronto, Ontario.[70]

- Festival d’Anères inAnères,France.[71]

- Hippodrome Silent Film Festival inFalkirk, Scotland.[72]

- Internationale Stummfilmtage (International Days of Silent Cinema), which is held every August inBonn, Germany.[73]

- Le Giornate del cinema muto (Pordenone Silent Film Festival), held annually inPordenone, Italy.It is the first and largest international film festival dedicated to the preservation, dispersion, and study of silent film.[74]

- Mykkäelokuvafestivaalit (International Silent Film Festival, Forssa) held inForssa,Finland.[75]

- Nederlands Silent Film Festival held inEindhoven,Nederlands.[76]

- The Slapstick Film Festival held inBristol, UK.[77]

- Stummfilm Festival Karlsruhe held inKarlsruhe, Germany.[78]

See also

[edit]- Category:Silent films

- Category:Silent film actors

- African American women in the silent film era

- Classic Images

- Laurel and Hardy films

- List of film formats

- German Expressionism

- Kammerspielfilm

- List of silent films released on 8 mm or Super 8 mm film

- List of early sound feature films (1926–1929)

- List of black-and-white films produced since 1966

- Lost films

- Melodrama

- Sound film

- Sound stage

- Tab show

- "At the Moving Picture Ball"– song about silent film stars)

References

[edit]- ^Torres-Pruñonosa, Jose; Plaza-Navas, Miquel-Angel; Brown, Silas (2022)."Jehovah's Witnesses' adoption of digitally-mediated services during Covid-19 pandemic".Cogent Social Sciences.8(1).doi:10.1080/23311886.2022.2071034.hdl:10261/268521.S2CID248581687.

synchronised sound in the silent-movie era (accomplished by playing a gramophone while manually adjusting the projector's frame rate for lip synchronisation)

- ^"Silent Films".JSTOR.Archived fromthe originalon May 26, 2019.RetrievedOctober 29,2019.

- ^Slide 2000,p. 5.

- ^abcdefgLewis 2008.

- ^Dellman, Sarah (2016)."Lecturing without an Expert"(PDF).The Magic Lantern Gazette.

- ^abDirks, Tim."Film History of the 1920s, Part 1".AMC.Archivedfrom the original on February 20, 2014.RetrievedMarch 7,2014.

- ^Brownlow 1968b,p. 580.

- ^Harris, Paul (December 4, 2013)."Library of Congress: 75% of Silent Films Lost".Variety.Archivedfrom the original on August 21, 2017.RetrievedJuly 27,2017.

- ^S., Lea (January 5, 2015)."How Do Silent Films Become 'Lost'?".Silent-ology.Archivedfrom the original on February 24, 2018.RetrievedJuly 27,2017.

- ^Jeremy Polacek (June 6, 2014)."Faster than Sound: Color in the Age of Silent Film".Hyperallergic.Archivedfrom the original on December 22, 2015.RetrievedDecember 14,2015.

- ^Vlad Strukov, "A Journey through Time: Alexander Sokurov'sRussian Arkand Theories of Memisis "in Lúcia Nagib and Cecília Mello, eds.Realism and the Audiovisual Media(NY: Palgrave Macmillan, 2009), 129–30.ISBN0230246974;and Thomas Elsaesser,Early Cinema: Space, Frame, Narrative(London: British Film Institute, 1990), 14.ISBN0851702457

- ^Foster, Diana (November 19, 2014)."The History of Silent Movies and Subtitles".Video Caption Corporation.Archivedfrom the original on February 25, 2019.RetrievedFebruary 24,2019.

- ^Cook 1990.

- ^Miller, Mary K. (April 2002)."It's a Wurlitzer".Smithsonian.RetrievedFebruary 24,2018.

- ^Eyman 1997.

- ^Marks 1997.

- ^Parkinson 1996,p. 69.

- ^Standish 2006,p. 68.

- ^"Silent Film Musicians Directory".Brenton Film.February 10, 2016.Archivedfrom the original on February 25, 2021.RetrievedMay 25,2016.

- ^"About".Silent Film Sound & Music Archive.Archivedfrom the original on June 17, 2016.RetrievedFebruary 24,2018.

- ^abBrownlow 1968a,pp. 344–353.

- ^"Lon Chaney".www.tcm.com.Archivedfrom the original on June 30, 2022.RetrievedJune 4,2022.

- ^Kaes 1990.

- ^abcdefBrownlow, Kevin(Summer 1980)."Silent Films: What Was the Right Speed?".Sight & Sound.pp. 164–167. Archived fromthe originalon November 9, 2011.RetrievedMarch 24,2018.

- ^Card, James (October 1955)."Silent Film Speed".Image:5–56. Archived fromthe originalon April 7, 2007.RetrievedMay 9,2007.

- ^Read & Meyer 2000,pp. 24–26.

- ^DirectorGus Van Santdescribes in his director commentary onPsycho: Collector's Edition(1998) that he and his generation were likely turned off to silent film because of incorrect TV broadcast speeds.

- ^Erickson, Glenn (May 1, 2010)."Metropolis and the Frame Rate Issue".DVD Talk.Archivedfrom the original on October 11, 2018.RetrievedOctober 11,2018.

- ^"Annabelle Whitford".Internet Broadway Database.Archivedfrom the original on March 8, 2014.RetrievedMarch 7,2014.

- ^Current & Current 1997.

- ^Bromberg & Lang 2012.

- ^Duvall, Gilles; Wemaere, Severine (March 27, 2012).A Trip to the Moon in its Original 1902 Colors.Technicolor Foundation for Cinema Heritage and Flicker Alley. pp. 18–19.

- ^abcRevised List of High-Class Original Motion Picture Films(1908),sales catalog of unspecified film distributor (United States, 1908), pp. [4], 191. Internet Archive. Retrieved July 7, 2020.

- ^Kahn, Eve M. (August 15, 2013)."Getting a Close-Up of the Silent-Film Era".The New York Times.Archivedfrom the original on December 1, 2017.RetrievedNovember 29,2017.

- ^"Biggest Money Pictures".Variety.June 21, 1932. p. 1.Cited in"Biggest Money Pictures".Cinemaweb. Archived fromthe originalon July 8, 2011.RetrievedJuly 14,2011.

- ^Carr, Jay."The Silent Enemy".Turner Classic Movies.Archivedfrom the original on September 12, 2017.RetrievedSeptember 11,2017.

- ^Schrom, Benjamin."The Silent Enemy".San Francisco Silent Film Festival.Archived fromthe originalon January 31, 2020.RetrievedSeptember 11,2017.

- ^JuhaatIMDb

- ^PushpakatIMDb

- ^"About the Show".Silent Laughter. 2004.Archivedfrom the original on March 12, 2014.RetrievedMarch 7,2014.

- ^Zinoman, Jason(February 23, 2005)."Lost in a Theatrical World of Slapstick and Magic".The New York Times.RetrievedMarch 7,2014.

- ^On Screen: The Call of Cthulhu DVDArchivedMarch 25, 2009, at theWayback Machine

- ^"Interview with Michel Hazanavicius"(PDF).English press kit The Artist.Wild Bunch.Archived fromthe original(PDF)on September 14, 2011.RetrievedMay 10,2011.

- ^"Sangivorous".Film Smash. December 8, 2012.Archivedfrom the original on December 11, 2013.RetrievedMarch 7,2014.

- ^"School of Film Spotlight Series: Sanguivorous"(Press release).University of the Arts.April 4, 2013. Archived fromthe originalon October 2, 2013.RetrievedMarch 7,2014.

- ^"Sanguivorous".Folio Weekly.Jacksonville, Florida. October 19, 2013. Archived fromthe originalon November 9, 2013.RetrievedMarch 7,2014.

- ^Sanchez, Diana."Blancanieves".Toronto International Film Festival.Archived fromthe originalon August 26, 2012.RetrievedFebruary 6,2023.

- ^"Another Silent Film to Come Out in 2011:" Silent Life "Moves up Release Date"(Press release). Rudolph Valentino Productions. November 22, 2011.RetrievedMarch 7,2014.

- ^Silent life official web siteArchivedMarch 8, 2014, at theWayback Machine

- ^Schaefer, Brian (March 23, 2018)."Will the Spirit of Burning Man Art Survive in Museums?".The New York Times.Archivedfrom the original on June 12, 2020.RetrievedJune 12,2020.

- ^"About Us".American Theater Organ Society.Archivedfrom the original on October 29, 2013.RetrievedMarch 7,2014.

- ^Globe International Silent Film Festival wikipedia

- ^"Silent Feature Film SILENT TIMES Is the First of Its Kind in 80 Years"ArchivedDecember 10, 2018, at theWayback Machine(April 30, 2018).Broadway World.com.Retrieved January 20, 2019.

- ^Dunne, Susan (May 19, 2018)."World Premiere of Silent Film at Mystic-Noank Library."ArchivedDecember 10, 2018, at theWayback MachineHartford Courant.Retrieved from Courant.com, January 23, 2019.

- ^"Mystic & Noank Library Showing Silent Film Shot in Mystic, Westerly"ArchivedDecember 10, 2018, at theWayback Machine(May 24, 2018).TheDay.com.Retrieved January 23, 2019.

- ^"Library Reports on America's Endangered Silent-Film Heritage".News from the Library of Congress(Press release). Library of Congress. December 4, 2013.ISSN0731-3527.RetrievedMarch 7,2014.

- ^Thompson 1996,pp. 12–18.

- ^Thompson 1996,pp. 68–78.

- ^Thompson 1996,pp. 186–200.

- ^"Ben Model interview on Outsight Radio Hours".RetrievedAugust 4,2013– via Archive.org.

- ^abKula 1979.

- ^"A different sort of Klondike treasure – Yukon News".May 24, 2013.Archivedfrom the original on June 20, 2017.RetrievedFebruary 25,2018.

- ^Morrison 2016,1:53:45.

- ^Weschler, Lawrence (September 14, 2016)."The Discovery, and Remarkable Recovery, of the King Tut's Tomb of Silent-Era Cinema".Vanity Fair.RetrievedJuly 20,2017.

- ^Slide 2000,p. 99.

- ^-Only verified active festivals are included; please consult individual sites to see if the festivals are still active.- Women Film Pioneers Project, 'Silent Film Organizations, Festivals & Conferences'https://wfpp.columbia.edu/silent-film-organizations-festivals-conferences/#FILM_FESTIVALS_CONFERENCES_SCREENING_RESOURCES

- ^Capitolfesthttps://www.romecapitol.com/capitolfest/

- ^Kansas Silent Film Festival,http://www.kssilentfilmfest.org/

- ^San Francisco Silent Film Festival,https://silentfilm.org/

- ^Toronto Silent Film Festival,http://www.torontosilentfilmfestival.com/

- ^"Festival d'Anères".www.festival-aneres.fr.RetrievedFebruary 20,2024.

- ^"Hippodrome".website.RetrievedFebruary 20,2024.

- ^"Home EN".www.internationale-stummfilmtage.de.RetrievedFebruary 20,2024.

- ^"GCM HOME pre 2024".Le Giornate del Cinema Muto.RetrievedFebruary 20,2024.

- ^"Etusivu | Mykkäelokuvafestivaalit 21.8.-27.8.2023 Forssassa".www.forssasilentmovie.com.RetrievedFebruary 20,2024.

- ^"Home - Nederlands Silent Film Festival".nsff.nl(in Dutch). October 24, 2022.RetrievedFebruary 20,2024.

- ^"Slapstick Festival Bristol | Silent Film & Visual Comedy Festival".slapstick.org.uk.March 29, 2021.RetrievedFebruary 20,2024.

- ^"Willkommen beim Stummfilmfestival Karlsruhe".Stummfilmfestival Karlsruhe(in German). February 26, 2018.RetrievedFebruary 20,2024.

Bibliography

[edit]- Bromberg, Serge, Lang, Eric (directors) (2012).The Extraordinary Voyage(DVD). MKS/Steamboat Films.

- Brownlow, Kevin(1968a).The Parade's Gone By...New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

- ———(1968b).The People on the Brook.New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

- Cook, David A. (1990).A History of Narrative Film(2nd ed.). New York: W.W. Norton.ISBN978-0-393-95553-8.

- Current, Richard Nelson;Current, Marcia Ewing (1997).Loie Fuller: Goddess of Light.Boston: Northeastern University Press.ISBN978-1-55553-309-0.

- Eyman, Scott(1997).The Speed of Sound: Hollywood and the Talkie Revolution, 1926–1930.New York: Simon & Schuster.ISBN978-0-684-81162-8.

- Kaes, Anton (1990). "Silent Cinema".Monatshefte.82(3): 246–256.ISSN1934-2810.JSTOR30155279.

- Kobel, Peter (2007).Silent Movies: The Birth of Film and the Triumph of Movie Culture(1st ed.). New York: Little, Brown and Company.ISBN978-0-316-11791-3.

- Kula, Sam (1979)."Rescued from the Permafrost: The Dawson Collection of Motion Pictures".Archivaria(8). Association of Canadian Archivists: 141–148.ISSN1923-6409.Archivedfrom the original on October 20, 2014.RetrievedMarch 7,2014.

- Lewis, John (2008).American Film: A History(1st ed.). New York: W. W. Norton & Company.ISBN978-0-393-97922-0.

- Marks, Martin Miller (1997).Music and the Silent Film: Contexts and Case Studies, 1895–1924.New York: Oxford University Press.ISBN978-0-19-506891-7.

- Morrison, Bill(2016).Dawson City: Frozen Time.KinoLorber.

- Musser, Charles(1990).The Emergence of Cinema: The American Screen to 1907.New York: Charles Scribner's Sons.

- Parkinson, David (1996).History of Film.New York: Thames and Hudson.ISBN978-0-500-20277-7.

- Read, Paul; Meyer, Mark-Paul, eds. (2000).Restoration of Motion Picture Film.Conservation and Museology. Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann.ISBN978-0-7506-2793-1.

- Slide, Anthony(2000).Nitrate Won't Wait: A History of Film Preservation in the United States.Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co.ISBN978-0-7864-0836-8.

- Standish, Isolde (2006).A New History of Japanese Cinema: A Century of Narrative Film.New York: Continuum.ISBN978-0-8264-1790-9.

- Thompson, Frank T. (1996).Lost Films: Important Movies That Disappeared.New York: Carol Publishing.ISBN978-0-8065-1604-2.

- Brownlow, Kevin(1980).Hollywood: The Pioneers.New York: Alfred A. Knopf.ISBN978-0-394-50851-1.

- Corne, Jonah (2011). "Gods and Nobodies: Extras, the October Jubilee, and Von Sternberg'sThe Last Command".Film International.9(6).ISSN1651-6826.

- Davis, Lon (2008).Silent Lives.Albany, New York: BearManor Media.ISBN978-1-59393-124-7.

- Everson, William K.(1978).American Silent Film.New York: Oxford University Press.ISBN978-0-19-502348-0.

- Mallozzi, Vincent M. (February 14, 2009)."Note by Note, He Keeps the Silent-Film Era Alive".The New York Times.p. A35.Archivedfrom the original on January 11, 2015.RetrievedSeptember 11,2013.

- Stevenson, Diane (2011). "Three Versions ofStella Dallas".Film International.9(6).ISSN1651-6826.

- Toles, George (2011). "Cocoon of Fire: Awakening to Love in Murnau'sSunrise".Film International.9(6).ISSN1651-6826.

- Usai, Paolo Cherchi (2000).Silent Cinema: An Introduction(2nd ed.). London: British Film Institute.ISBN978-0-85170-745-7.