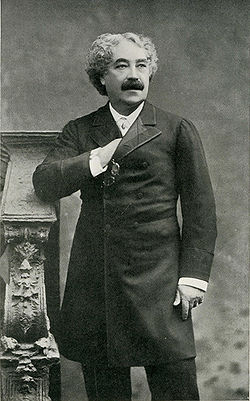

Sims Reeves

John Sims Reeves(21 October 1821[1]– 25 October 1900) was an Englishoperatic,oratorioand balladtenorvocalist during the mid-Victorian era.

Reeves began his singing career in 1838 but continued his vocal studies until 1847. He soon established himself on the opera and concert stage and became known for his interpretation of ballads. He continued singing through the 1880s and later taught and wrote about singing.

Musical beginnings

[edit]Sims Reeves was born inShooter's Hill,in Kent, England. His parents were John Reeves, a musician of Yorkshire origin, and his wife, Rosina. He received his earliest musical education from his father, a bass soloist in theRoyal ArtilleryBand, and probably through the bandmaster, George McKenzie.[2]By the age of fourteen he was appointed choirmaster ofNorth Craychurch and performed organist's duties.[3]He seems to have studied medicine for a year but changed his mind when he gained his adult voice: it was at first abaritone,training underThomas Simpson Cooke.He also learntoboe,bassoon,violin,celloand other instruments. He later studied piano underJohann Baptist Cramer.[4]

He made his earliest appearance atNewcastlein 1838 or 1839[5]as the Gipsy boy inHenry Bishop'sGuy Mannering,and as Count Rodolfo inLa sonnambula(baritone parts). Later he performed at the Grecian Saloon, London, under the name of Johnson.[6]He continued to study voice with Messrs. Hobbs and T. Cooke and appeared underWilliam Macready's management atDrury Lane(1841–1843) in subordinate parts in spoken theatre and inHenry Purcell'sKing Arthur( "Come if you dare" ),Der Freischütz(as Ottokar), andAcis and Galateain 1842 whenHandel's pastoral was mounted on the stage withClarkson Frederick Stanfield's scenery.[7]

In summer 1843 Reeves studied in Paris under the tenor and pedagogueMarco Bordogniof theParis Conservatoire.[6]Bordogni was responsible for opening and developing the upper (tenor) octave of his voice into the famous rich and brilliant head notes.[8]From October 1843 to January 1844 Reeves appeared in a very varied programme of musical drama, including the roles of Elvino inLa sonnambulaand Tom Tug inCharles Dibdin'sThe Waterman,at theManchestertheatre, and over the next two years also performed in Dublin, Liverpool and elsewhere in the provinces.[9]In the same period, especially from 1845, he continued his studies abroad, notably underAlberto Mazzucato(1813–1877), the dramatic composer and teacher then newly appointed singing instructor at theMilanConservatory.[10]

His debut in Italian opera was made on 29 October 1846 atLa Scalain Milan as Edgardo inDonizetti'sLucia di Lammermoor,partnered byCatherine Hayes:he received a fine reception, andGiovanni Battista Rubinipaid his respects in person.[11](This role became Reeves's greatest, and his wife therefore nicknamed him 'Gardie'.)[12]For six months he sang at the principal Italian opera houses, and finally inVienna,where he was rescued from his contract and returned to England.[13]

1844–1848: English debuts in opera and concert

[edit]He returned to London in 1847, appearing in May at abenefit concertforWilliam Vincent Wallace,and in June at one of the 'Antient Concerts'. In September 1847 he sang in Edinburgh withJenny Lind.[6]His first principal role on the English operatic stage was withLouis-Antoine Jullien's English Opera company atDrury Lane Theatrein December 1847 inLucia,in English text, with Mme Doras Gras (Lucia) andWilloughby Weiss,winning immediate and near-universal acclaim, not least fromHector Berlioz,who conducted the performance. (Berlioz mistook him for an Irishman.)[14]In the same season, inBalfe'sThe Maid of Honour(based on the subject ofFlotow'sMartha), he created the part of Lyonnel.[15]In May 1848 he joinedBenjamin Lumley's company atHer Majesty's Theatreand sangLinda di ChamounixwithEugenia Tadolini,but he severed the connection whenItalo Gardoniwas brought in to sing Edgardo inLuciaopposite Jenny Lind.[16]But that autumn in Manchester he sang inLuciaandLa sonnambula,days after Lind appeared in the same works there, and Reeves obtained the better houses.[17]Reeves sangLa sonnambulaandLuciaat Covent Garden in October.

Inoratorio,Reeves first sangMessiahinGlasgow,Scotland, during 1844.[18]In February 1848 he sang Handel'sJudas Maccabaeus,atExeter HallforJohn Pyke Hullah,Acis and Galateain March andJephthain April and May.[19]He was, meanwhile establishing himself as the leading ballad-singer in England. In September 1848 at theWorcesterfestival he took a solo inElijah,and sang inBeethoven'sChrist on the Mount of Olives,and packed the hall in a recital ofOberon.[20]At theNorwichFestival he was sensational inElijahandIsrael in Egypt.After his November appearance at theSacred Harmonic SocietyinJudas Maccabaeus,a critic wrote, 'the mantle ofBrahamis destined to fall' (on Reeves).[21]CriticHenry Chorleywrote that Reeves had created 'a positive revolution in the interpretation of Handel's oratorios.'[22]

Italian opera

[edit]Reeves toured in Dublin at Theatre Royal in 1849, for Mr Calcraft. After his successful engagement he attended the debut there of the Irish sopranoCatherine Hayes,inLucia:herEdgardo,Sig. Paglieri, was hissed from the stage, and Reeves was obliged to stand in for the performance.[23]His LondonCovent GardenItalian debut was in 1849, asElvinoinBellini'sLa sonnambula,oppositeFanny Tacchinardi Persiani(the creator of the title role inLucia): he made a great effect of full lyrical declamation inTutto e sciolto... Ah! perche non-posso odiarti?.After hisEdgardoinLucia,Reeves'Elvinowas generally considered his finest role in Italian opera.[24]In the winter of 1849 he returned to English opera, and in 1850 at Her Majesty's he made a further great success inVerdi'sErnani,opposite theElviraof Mdlle Parodi andCarloofGiovanni Belletti,[25]who was about to embark on an American tour at the invitation of Jenny Lind. In encores, the cry of 'Reeves!' became widespread.

On 2 November 1850, he married Charlotte Emma Lucombe (1823–1895), a soprano who had a brief but brilliant season at the Sacred Harmonic Society and had joined the same company as Reeves at Covent Garden.[26]There she appeared with success as Haydee inAuber's opera, and remained on the stage for four or five years after their marriage. Emma Reeves idolised her husband and in later years became almost obsessively attentive to his comfort and reputation.[27]In February 1851 they returned to Dublin, where Reeves was to have performed with the sopranoGiulia Grisi:she, however, was indisposed, and Mr. and Mrs. Reeves appeared together there instead in the lead roles inLucia di Lammermoor,La Sonnambula,Ernaniand Bellini'sI Puritani.Reeves also played thereMacheathin theBeggar's Opera.[28]Emma and Sims Reeves had five children, of whom Herbert Sims Reeves and Constance Sims Reeves became professional singers.[6]

Dublin was followed immediately by Lumley engagements at theThéâtre des Italiens,Paris, where he sangErnani,Carlo inLinda di Chamounix(oppositeHenriette Sontag) andGennaroin Donizetti'sLucrezia Borgia.[29]In 1851 Reeves sang Florestan inFideliotoSophie Cruvelli's Leonore, and some thought he outshone her.[30]

1850s: focus on concerts

[edit]During the next three decades, Reeves was the leading tenor in Britain. He had the honour of singing privately forQueen VictoriaandPrince Albert.Michael Costa,Arthur Sullivanand the other leading British composers of the period wrote tenor parts specifically for him. He could command fees as high as £200 per week for his appearances.[6]

Reeves was generous to younger singers, and this generosity later redounded to his own benefit. In around 1850, Reeves gave encouragement toJames Henry Mapleson,who applied to him for advice as a singer, sending him off to study with Mazzucato at theMilanconservatory.[31]In 1855 he gave the youngCharles Santleyfriendly encouragement, recommending that he should contact Lamperti in his forthcoming studies in Italy,[32]and they were afterwards introduced during the interval of aRoyal Philharmonicconcert.[33]Reeves's concert association with Santley continued until the last year of his life. Mapleson, who became an important theatre manager, promoted Reeves's operatic appearances of the 1860s.

During the 1850s, Reeves's career moved away from the stage and increasingly focused upon concert work. Reeves sang throughout the English provinces.Michael Costa(afterwardsSirMichael) composed two oratorios for theBirmingham Triennial Music Festivalwith lead tenor parts written for Reeves. The first,Eli,was presented in 1855, and (unusually in oratorio) encores were demanded. The effect of the solo and chorusPhilistines, Hark the Trumpet Soundingwas electric, and was witnessed in the audience by the three great Italian tenorsMario,Gardoni andEnrico Tamberlikwith astonishment.[34]

Reeves scored his greatest triumphs in oratorio at the Handel Festivals atThe Crystal Palace.At the inaugural festival of June 1857 he deliveredMessiah,Israel in EgyptandJudas Maccabaeus,and these were repeated at the Handel centennial festival of 1859, when he was in company with Willoughby Weiss, Clara Novello, MmeSainton-Dolbyand Giovanni Belletti. InSound an Alarmduring that festival, Reeves created a sensation, and the audience stood to applaud him. Yet theMusical Worldconsidered that his "The Enemy Said" fromIsrael in Egyptsurpassed even that, and was the vocal feat of the festival.[35]

At the opening of the Leeds Town Hall in 1858 he was a soloist in the premiere of the pastoraleThe May QueenbyWilliam Sterndale Bennett.

Return to the stage

[edit]

After a period of absence from the stage, in 1859–60 an English version ofGluck'sIphigénie en Taurideby H. F. Chorley was presented byCharles Halléat Manchester, with Reeves,Charles Santley,Belletti andCatherine Hayes,and two private performances were also given at thePark Lanehome of Lord Ward.[36]Mapleson had obtained Reeves, Santley andHelen Lemmens-Sherringtonfor a summer and winter season fromBenjamin Lumley,and in 1860 they had a major success inGeorge Macfarren'sRobin Hood(text byJohn Oxenford) at Her Majesty's, again under Hallé's direction. This new composition had several very effective passages written for Reeves in his role as Locksley, including "Englishmen by birth are free", "The grasping, rasping Norman race", "Thy gentle voice would lead me on", and a grand prison scena.[37]This proved more successful in ticket sales than the alternate Italian nights ofIl trovatoreandDon Giovannidespite the rival attractions of the sopranoThérèse Tietjensand the tenorAntonio Giuglini.

In 1862, Reeves presentedMazeppa,acantatawritten for him byMichael William Balfe.[38]In July 1863 Reeves appeared for Mapleson as Huon inOberon– the role written for Braham – with Tietjens,Marietta Alboni,Zelia Trebelli,Alessandro Bettini,Edouard Gassierand Santley.[39]After touring that winter as Huon, Edgardo and in the title role ofGounod'sFaust,(with Tietjens) inDublin,in 1864 he appeared at Her Majesty's inFaustand was especially complimented for the dramatic instinct of Faust's soliloquy in Act I and the superb energy of the duet with Mephistopheles which closes the Act. Reeves's reviewer in this role remarks on the fine condition of his voice at this date.[40]Although the criticEduard Hanslickwastoldthat the voice had already 'gone' in 1862,[41]Herman Kleinthought that it was still in its prime in 1866: 'a more exquisite illustration of what is termed the true Italian tenor quality it would be impossible to imagine: and this delicious sweetness, this rare combination of 'velvety' richness with ringing timbre, he retained in diminishing volume almost to the last.'[42]

Oratorio and cantata

[edit]In May 1862 atSt James's Hall,Reeves took part in what he believed was the first complete performance in England of theSt Matthew PassionofJ. S. Bach.This was underWilliam Sterndale Bennett,with Mme Sainton-Dolby, and Willoughby Weiss. Of this performance Reeves (who usually respected a composer's scoring absolutely) wrote:

'The tenor part... is in many places so unvocal, and the intervals are so awkward to take, that I was obliged to re-note it: without, of course, disturbing the accents or making it in any way unsuitable to the existing harmony. As soon as I had finished my work, to which I had devoted the greatest possible care, I submitted it to Bennett, who, except in one place, approved of all that I had done; and it was my version of the tenor part which was sung at Bennett's memorable performance, and which is still sung even to this day.'[43]

In Michael Costa's second oratorio for Reeves,Naaman(first performed autumn 1864), the soloists were Reeves,Adelina Patti(her first appearance in oratorio), Miss Palmer, and Santley. The quartet "Honour and Glory" was repeated by immediate and spontaneous demand.[44]Both oratorios probably owed their original success, and later comparative obscurity, to the fact that Reeves was their ideal interpreter, and with changing vocal fashions no successor could replace him adequately.[citation needed]In 1869 Reeves, Santley and Tietjens sang in the premiere of Arthur Sullivan's cantataThe Prodigal Son,at theWorcesterFestival. Santley considered Reeves's performance of the passage "I will arise and go to my father" a once-in-a-lifetime experience.[45]Reeves also sang in the premiere of Sullivan's oratorio,The Light of the World,together with Tietjens, Trebelli, and Santley.[46]

Reeves claimed close and primary association with several of the great tenor leads in the oratorios of Handel andMendelssohn.The songs "Men, Brothers and Fathers, Hearken to me" (fromSt Paul), and "The Enemy has Said" and "Sound an Alarm" (Judas Maccabaeus) were particular favourites,[47]and his friend RevArcher Thompson Gurneyalso extolled his "Waft her, angels" (Jephtha), his Samson and his Acis ( "Love in her eyes sits playing" ).[48]

Concert pitch debate

[edit]Reeves's declamation in The Crystal Palace was a main attraction and was repeated at each succeeding triennial festival until 1874. During the later 1860s Reeves felt it necessary to make public representations against the constantly increasing rise in Englishconcert pitch,which was by then half a tone higher than elsewhere in Europe and a full tone higher than in the age ofGluck.The pitch of the organ at the Birmingham Festival was (of necessity) lowered, after a similar reduction had been forced by senior artistes atDrury Lane.Singers such as Adelina Patti andChristina Nilssonmade similar demands. However Sir Michael Costa resisted the change, and Reeves finally withdrew his services from the Crystal Palace Handel Festivals, performed by the Sacred Harmonic Society, before the 1877 festival. For this reason he did not appear with the Sacred Harmonic Society thereafter.[49]

Later years

[edit]

In the winter of 1878–1879, he appeared with immense success inThe Beggar's Operaand inThe Waterman,at Covent Garden.[50]Edward Lloyd,who took Reeves's place as principal tenor at the Handel Festivals, sang with him, and with the tenorBen Davies,in a performance of the trio for tenor voices 'Evviva Bacco' by Curschmann, at a concert in St James's Hall in 1889.[51]

Reeves's retirement from public life, at first announced as to take place in 1882, did not actually occur until 1891. Then a farewell concert for his benefit was given at theRoyal Albert Hallin which Reeves himself performed, supported by Christine Nilsson, and at which he received a eulogy from SirHenry Irving.George Bernard Shawremarked that even then, in such Handelian airs asTotal Eclipse(Samson), 'he can still leave the next best tenor in England an immeasurable distance behind.'[52]The song "Come Into the Garden, Maud",which Balfe had written for him in 1857, appeared often in his late concerts.[53]

It is certain that Reeves stayed before the public long after his greatest powers had waned. He invested his savings in an unfortunate speculation, and he was compelled to reappear in public for a number of years. In his later career, he frequently withdrew from promised appearances owing to the effects of colds on his fragile vocal equipment, and through an unhappy susceptibility to the effects of nervousness. This also caused him financial difficulties: Besides the loss of income from the engagements, legal judgments for failure to perform were rendered against him, including in 1869 and 1871.[6]The accusation (which gained some currency) that he was given to drink was disavowed by his friend Sir Charles Santley.[54]

In 1890 Shaw stated that Reeves's many cancelled appearances were made entirely for the sake of pure artistic integrity 'which few appreciate fully', but left him at the head of his profession, and had required enormous efforts of artistic conviction, courage, and self-respect. He wrote of a performance ofBlumenthal'sThe Message,'In spite of all his husbandry, he has but few notes left now; yet the wonderfully telling effect and unique quality of those few still justify him as the one English singer who has worked in his own way, and at all costs, to attain and preserve ideal perfection of tone.'[55]

Klein said much the same as Shaw: 'To hear him, long after he had passed the age of seventy, sing "Adelaide" or "Deeper and Deeper Still" or "The Message" was an exposition of breath control, of tone-colouring, of phrasing and expression, that may truly be described as unique.'[56]Reeves sang in two concerts in the first season ofThe Proms,atQueen's Hallin 1895 (at which the lower continental pitch was employed). They were the only two concerts of that season that were sold out: all the others made at least £50 loss.[57]

In 1888, Reeves publishedSims Reeves, his Life and Recollections,followed byMy Jubilee, or, Fifty Years of Artistic Lifein 1889. At the same time, he became a teacher at the Guildhall School of Music and Drama. His 1900 book,On the Art of Singing,describes his pedagogic methods. After the death of his wife in 1895, he quickly married one of his students, Lucy Maud Madeleine Richard (b. 1873), and the couple toured South Africa the next year. Reeves died inWorthing,England, on 25 October 1900 and was cremated atWoking.[6]

His widow was brought byHarry Rickardsto Australia where, as Maud Sims Reeves, she performed songs made famous by her husband, such asSally in Our AlleyandCome into the Garden, Maude,then after the termination of her contract continued to perform in Western Australia, but became increasingly erratic. A paragraph in the AdelaideCritic,

The arrest of Mrs Sims Reeves in Kalgoorlie, and the fact that she has been placed under restraint on a suspicion of her being insane, will not surprise those who saw her perform in Melbourne. Her singing of her husband's songs was an extraordinary thing to see, if not to hear, and was accompanied with the most eccentric act imaginable. The audiences were deeply puzzled, striving quite earnestly to take the lady seriously because of the name she bore, but unable to reconcile the singer's extraordinary conduct with anything but low comedy.[58]

and repeated in other newspapers, resulted in a libel case, which she won but was left with a ruined reputation and loss of livelihood.[58]At some stage she had remarried was using the name Maud Allison Hartley.[59]

Vocal example and legacy

[edit]Braham'sThe Death of Nelsonwas prominent in Reeves' concert repertoire. Reeves was naturally aware that his career mirrored that of Braham, and remarked that, like Braham, his success had been many-sided, in opera, oratorio and ballad concerts.[60]The coincidence that his career had begun in the year of Braham's retirement, 1839, and the early reviews saying that he would inherit Braham's mantle, both shaped a prophecy and helped to fulfil it. Braham was a virtuoso of the old Italian school, able to deliver florid passages with intensity, accuracy and declamatory power. In 'assuming his mantle', Reeves consciously imitated his breadth of repertoire, and at his best had a very powerful and flexible declamation combined with great sweetness of tone and melodic power.Shawclassed his 'beautiful firmness and purity of tone' with Patti's and Santley's.[61]Sir Henry Wood compared thecaressingnature of his voice withRichard Tauber's, adding, 'I never hear the title ofDeeper and deeper still(Handel) without thinking of his lovely inflection and quality.'[62]

In the Handel tenor roles, his immediate successor in the Crystal Palace performances, until 1900, was the English tenorEdward Lloyd,who recorded "Sound an Alarm", "Lend me your Aid" (Gounod – "Reine de Saba" ), the tenor solos fromElijah,Braham'sDeath of Nelson,Dibdin'sTom Bowlingand ballads of the declamatory style (such asFrederic Clay's "I'll sing thee songs of Araby"; "Alice, Where Art Thou?"and" Come into the Garden, Maud ") – all closely identified with Reeves – in the first years of the twentieth century.[63]In 1903 Herman Klein wrote that 'The mantle of Braham and Sims Reeves, worthily borne by Edward Lloyd, was resting more or less easily upon the shoulders ofBen Davies,a singer whose rare musical instinct and intelligence have always partially atoned for his uneven scale and his lack of ringing head-notes.'[64](Possibly this suggests some comparison to their great predecessors, in Lloyd's and Davies's style of declamation.) However Klein later admitted that neither Lloyd nor Davies ever laid claim to be Reeves's successor.[65]

Reeves was a member of theGarrick Club,where in his younger days he associated withWilliam Makepeace Thackeray,Charles Dickens,Thomas Talfourd,Charles Kemble,Charles Kean,Albert SmithandShirley Brooks.[66]

References

[edit]- ^Date thus in Reeves,The Life of J. Sims Reeves, Written by Himself(1888), p. 15: see also Reeves,My Jubilee(1889), p. 20, 'In 1839, when I had just entered upon my eighteenth year...' (i.e., his 17th birthday was in October 1838). But C. E. Pearce, inSims Reeves – Fifty Years of Music in Englandpp. 17–18, (followed by most) shows aWoolwichparish baptism record (not birth) for 26 September 1818, of one John Reeves. If that was really the singer, that makes Reeves' and his oldest friends' statements unreliable, and postpones his voice breaking to age 16 against his direct statement this occurred age 12 (ibid. p. 20). John Reeves (1818) was possibly a sibling deceased before 1821.

- ^C. Pearce 1924, pp. 18–22.

- ^J. Sims Reeves,The Life of J. Sims Reeves, Written by Himself(Simpkin, Marshall & Co, London 1888, p. 16.

- ^Reeves 1888, p. 16.

- ^See Pearce 1924, pp. 28–30.

- ^abcdefgBiddlecombe, George."Reeves, (John) Sims (1818–1900)",Oxford Dictionary of National Biography,Oxford University Press, 2004, accessed 26 September 2008,doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/23308

- ^Pearce 1924, p. 44.

- ^Pearce 1924, p. 37).

- ^Pearce 1924, pp. 68–74.

- ^Reeves 1888, p. 32: Rosenthal & Warrack 1974, p. 331.

- ^Reeves 1888, p. 33.

- ^Santley 1909, pp. 83–87.

- ^Pearce 1924, pp. 83–84.

- ^Reeves 1888, pp. 60–65.

- ^Reeves 1888, pp. 65–68.

- ^Pearce 1924, pp. 117–23.

- ^Pearce 1924, pp. 128–29.

- ^Pearce 1924, p. 69.

- ^Reeves 1888, pp. 80–81; Pearce 1924, pp. 112–14.

- ^Pearce 1924, pp. 124–27.

- ^Reeves 1888, p. 82. Braham made his formal farewell to the public in 1839.

- ^Reeves 1888, p. 83.

- ^Reeves 1888, pp. 125–34.

- ^Reeves 1888, pp. 161–65.

- ^Reeves 1888, pp. 175–77.

- ^Reeves 1888, pp. 177–78.

- ^Santley 1909, pp. 79–87: Mapleson 1888, I, pp. 74–76.

- ^Reeves 1888, p. 190.

- ^Reeves 1888, pp. 201–02.

- ^Chorley 1862, II, p. 142.

- ^Mapleson 1888, I, p. 4.

- ^Santley 1893, p. 60.

- ^Santley 1892, p. 36.

- ^Reeves 1888, pp. 214–16.

- ^Reeves 1888, pp. 229–31.

- ^Santley 1892, p. 169.

- ^Reeves 1888, pp. 214 and 220–228.

- ^Reeves 1888, p. 231.

- ^Santley 1892, pp. 199–200.

- ^Reeves 1888, pp. 231–33: Santley 1892, pp. 201–03 and 206-07.

- ^Quoted by M. Scott 1977, p. 49.

- ^Klein 1903, pp. 460–61.

- ^S. Reeves 1889, pp. 178–79.

- ^Reeves 1888, pp. 216–19.

- ^Santley 1892, pp. 277–78.

- ^Introduction toThe Light of the WorldArchived16 December 2008 atarchive.today,The Gilbert and Sullivan Archive (2008)

- ^Reeves 1888, pp. 219–20,

- ^Reeves 1888, pp. 203–05: see also Klein 1903, pp. 7 and 462.

- ^Reeves 1888, pp. 242–52.: cf also ODNB.

- ^Reeves 1888, pp. 213–14 and 252-55.

- ^Pearce 1924, p. 24.

- ^Shaw 1932, i, pp. 191–92.

- ^Scott, Derek B."Come into the Garden, Maud" (1857),The Victorian Web,10 September 2007

- ^Santley 1909, pp. 88–97.

- ^G. B. Shaw 1932, i, p. 191.

- ^Klein 1903, p. 462.

- ^R. Elkin,Queen's Hall 1893–1944(Rider, London 1944), p. 25.

- ^ab"Supreme Court of Tasmania".Tasmanian News.No. 7824. Tasmania, Australia. 20 June 1906. p. 4.Retrieved14 January2024– via National Library of Australia.

- ^"Libel Action".Truth (Brisbane newspaper).No. 298. Queensland, Australia. 8 October 1905. p. 3.Retrieved14 January2024– via National Library of Australia.

- ^Reeves 1888, p. 214.

- ^Shaw 1932, iii, pp. 255–56.

- ^H. J. Wood,My Life of Music(London: Victor Gollancz Ltd 1946 edition), p. 82–83.

- ^Scott 1977.

- ^Herman Klein (Thirty Years,pp. 467–68).

- ^H. Klein, 'Sims Reeves: "Prince of English tenors",' in R. Wimbush (comp.),The Gramophone Jubilee Book 1923–1973(General Gramophone Publications Ltd, Harrow 1973), 109–112.

- ^Reeves 1889, pp. 146–47.

Sources

[edit]- H. F. Chorley,Thirty Years' Musical Recollections(Hurst and Blackett, London 1862).

- H. S. Edwards,The life and artistic career of Sims Reeves(1881)

- R. Elkin,Queen's Hall 1893–1941(Rider, London 1944)

- Arthur Jacobs,Arthur Sullivan: a Victorian musician,2nd edn (Constable & Co, London 1992)

- H. Klein,Thirty Years of Musical Life in London(Century Co., New York 1903)

- R. H. Legge and W. E. Hansell,Annals of the Norfolk and Norwich triennial musical festivals(1896), pp. 116 and 144

- J. H. Mapleson,The Mapleson Memoirs, 2 vols(Belford, Clarke & Co, Chicago and New York 1888).

- Charles E. Pearce,Sims Reeves – Fifty Years of Music in England(Stanley Paul, 1924)

- S. Reeves, 1888,Sims Reeves, His Life and Recollections, Written by Himself(8th Edn, London 1888).

- S. Reeves,My Jubilee: Or, Fifty Years of Artistic Life(Music Publishing Co. Ltd, London 1889).

- S. Reeves,On the art of singing(1900)

- C. Santley, 1892,Student and Singer, The Reminiscences of Charles Santley(Edward Arnold, London 1892).

- C. Santley, 1909,Reminiscences of my Life(London, Pitman).

- M. Scott, 1977,The Record of Singingto 1914(London, Duckworth), 48–49.

- G. B. Shaw, 1932,Music in London 1890–94 by Bernard Shaw,Standard Edition 3 Vols

- The Athenaeum,7 November 1868, p. 610; and 3 November 1900, p. 586

External links

[edit]- Sims Reeves, His Life and Recollections, text on Google Books

- Sims Reeves, My Jubilee: 50 Years of Musical Life, facsimile text from Open Library

- "Sigh no more, Ladies"[dead link],The Gilbert and Sullivan Archive (2004) (a song dedicated by Sullivan to Reeves in 1866, with photograph of, and information about, Reeves)

- "Once Again",The Gilbert and Sullivan Archive (2004) (a song written "expressly for" Reeves by Sullivan in 1872)

- Portraits of Sims Reeves (NPG)