Skhul and Qafzeh hominins

32°41′18″N35°19′06″E/ 32.68833°N 35.31833°E

TheSkhul and Qafzeh homininsorQafzeh–Skhul early modern humans[1]arehomininfossilsdiscovered inEs-SkhulandQafzehcaves inIsrael.They are today classified asHomo sapiens,among the earliest of their species in Eurasia. Skhul Cave is on the slopes ofMount Carmel;Qafzeh Cave is a rockshelter nearNazarethinLower Galilee.

The remains found at Es Skhul, together with those found at theNahal Me'arot Nature ReserveandMugharet el-Zuttiyeh,were classified in 1939 byArthur KeithandTheodore D. McCownasPalaeoanthropus palestinensis,a descendant ofHomo heidelbergensis.[2][3][4]

History

[edit]−10 — – −9 — – −8 — – −7 — – −6 — – −5 — – −4 — – −3 — – −2 — – −1 — – 0 — |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The remains exhibit a mix of traits found inarchaicandanatomically modern humans.They have been tentatively dated at about 80,000–120,000 years old usingelectron paramagnetic resonanceandthermoluminescence datingtechniques.[5]The brain case is similar to modern humans, but they possess brow ridges and a projecting facial profile likeNeanderthals.They were initially regarded as transitional from Neanderthals toanatomically modern humans,or ashybrids between Neanderthals and modern humans.Neanderthal remains have been found nearby atKebara Cavethat date to 61,000–48,000 years ago,[6]but it has been hypothesised that the Skhul/Qafzeh hominids had died out by 80,000 years ago because of drying and cooling conditions, favouring a return of a Neanderthal population[7]suggesting that the two types of hominids never made contact in the region. A more recent hypothesis is that Skhul/Qafzeh hominids represent the first exodus of modern humans fromAfricaaround 125,000 years ago, probably via theSinai Peninsula,and that the robust features exhibited by the Skhul/Qafzeh hominids represent archaic sapiens features rather than Neanderthal features.[7]The discovery of modern human made tools from about 125,000 years ago atJebel Faya,United Arab Emirates, in the Arabian Peninsula, may be from an even earlier exit of modern humans from Africa.[8]In January 2018 it was announced that modern human finds at the Mount Carmel cave ofMisliya,discovered in 2002, had been dated to around 185,000 years ago, giving an even earlier date for an out-of-Africa migration.[9][10][11][12]

Ian Wallace andJohn Sheahave devised a methodology for examining the various Middle paleolithic core assemblages present at the Levant site in order to test whether the different hominid populations had distinct mobility patterns. They use a ratio of "formal" and "expedient"coreswithin assemblages to demonstrate either earlyHomo sapiensor Neanderthal mobility patterns, and thus categorize site occupations.[13]In 2005, a set of 7 teeth fromTabun Cavein Israel were studied and found to most likely belong to a Neanderthal that may have lived around 90,000 years ago,[14]and another Neanderthal (C1) from Tabun was estimated to be ~122,000 years old.[15]If the dates are correct for these individuals, then it is possible that Neanderthals and early moderns did make contact in the region and it may be possible that the Skhul and Qafzeh hominids are partially of Neanderthal descent. Non-African modern humans contain 1–4% Neanderthal genetic material, withhybridisationpossibly having taken place in theMiddle East.[16]It has been suggested, however, that the Skhul/Qafzeh hominids represent an extinct lineage. If this is the case, modern humans would have re-exited Africa around 70–50,000 years ago, crossing the narrowBab-el-Mandebstrait betweenEritreaand theArabian Peninsula.[7][17][18][19][20]This is the same route proposed to have been taken by the people who made the modern tools atJebel Faya.[8]

Skhul

[edit]The Skhul remains (Skhul 1–9) were discovered between 1929 and 1935 in theEs-Skhul CaveonMount Carmel.The remains of seven adults and three children were found, some of which (Skhul 1, 4, and 5) are claimed to have been burials.[21]Assemblages of perforatedNassariusshells (amarinegenus), which are significantly different from local fauna, have also been recovered from the area, suggesting that these people may have collected and employed the shells as beads,[22]as they are unlikely to have been used as food.[23]

Skhul Layer B has been dated to an average of 81,000–101,000 years ago with the electron spin resonance method, and to an average of 119,000 years ago with the thermoluminescence method.[24][25]

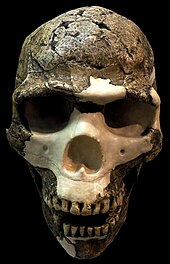

Skhul 5

[edit]Skhul 5 had themandibleof awild boaron its chest.[21]The skull displays prominent supraorbital ridges and jutting jaw, but the rounded braincase of modern humans. When found, it was assumed to be an advancedNeanderthal,but is today generally assumed to be a modern human, if a very robust one.[26]

Qafzeh

[edit]

Qafzeh caveopens onto a wall ofWadi el Hadjin the flank ofMount Precipice.Excavation of the cave byRené Neuvillebegan in 1934 and resulted in the discovery of the remains of 5 individuals in theMousterianstratigraphic levels, which was then called the Levalloiso-Mousterian[27](seeLevallosian). The lower layers of the cave were later dated to 92,000 years ago,[28]and a series of hearths, several human bodies, flint artifacts (side scrapers, disc cores, and points[29]), animal bones (gazelle, horse, fallow deer, wild ox, and rhinoceros[29]), a collection of sea shells, lumps of redochre,and an incised cortical flake were found.[28]

The remains of 15 hominids, 8 of them children, were recovered in total from Qafzeh within a Mousterian archaeological context and dated to ca. 95,000 years ago.[30]Remains of Qafzeh 8, 9, 10, 11, 13 and 15 were burials.[21]

The marine shells (Glycymerisbivalves) were brought from Mediterranean Sea shore some 35 km away, and were recovered from layers earlier than most of the bodies save one.[28]The shells were complete, naturally perforated, and several showed traces of having been strung (perhaps as a necklace), and a few had ochre stains on them.[28]

The various layers at Qafzeh were dated to an average of 96,000–115,000 years ago with the electron spin resonance method and 92,000 years ago with the thermoluminescence method.[24]

Qafzeh 9 and 10

[edit]Two skeletons were found in 1969 in the same burial, the skeleton of a late adolescent whose sex is debated (Qafzeh 9),[31]and the skeleton of a young child (Qafzeh 10).[27]Qafzeh 9 has a high forehead, lack of occipital bun, a distinct chin, but a prognathic face.[32]Qafzeh 9 offers the earliest evidence of associated mandibular and dental pathological conditions (i.e.non-ossifying fibromaof the mandible, pre-eruptive intracoronal resorption and osteochondritis dissecans of the temporomandibular joint) among early anatomically modern humans[33]

Qafzeh 11

[edit]

Found in 1971 was the body of an adolescent (aged about 13 years[34]) found in a pit dug in thebedrock.The skeleton was lying on its back, with the legs bent to the side and both hands placed on either side of the neck, and in the hands were the antlers of a largered deerclasped to the chest.[21][27]

Qafzeh 12

[edit]A child of about 3 years old who manifests with skeletal abnormalities that indicatehydrocephalus.[30]

Qafzeh 25

[edit]Qafzeh 25 was discovered in 1979. Due to his overall robustness and tooth wear, the remains are believed to be of a young male.[35]The fossil has undergone heavy taphonomical damages including a complete crushing of the skull and mandible.[36]Its inner ear morphology confirm that it is an anatomically modern human[37]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^Trinkaus, E.(1993)."Femoral neck-shaft angles of the Qafzeh-Skhul early modern humans, and activity levels among immature near eastern Middle Paleolithic hominids".Journal of Human Evolution.25(5).INIST-CNRS:393–416.doi:10.1006/jhev.1993.1058.ISSN0047-2484.

- ^The Palaeolithic Origins of Human Burial,Paul Pettitt,2013, p. 59

- ^Human Adaptation in the Asian Palaeolithic: Hominin Dispersal and Behaviour during the Late Quaternary,Ryan J. Rabett, 2012, p. 90

- ^The Stone Age of Mount Carmel: report of the Joint Expedition of the British School of Archaeology in Jerusalem and the American School of Prehistoric Research, 1929–1934,p. 18

- ^Lewin, Roger; Foley, Robert A. (2004).Principles of Human Evolution.Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing. p.385.ISBN978-0-632-04704-8.

- ^Bar-Yosef O.; Vandermeersch B.; Arensburg B.; Belfer-Cohen A.; Goldberg P.; Laville H.; Meignen L.; Rak Y.; Speth J. D.; et al. (1999)."The Excavations in Kebara Cave, Mt. Carmel [and Comments and Replies]".Current Anthropology.33(5): 497–550.doi:10.1086/204112.S2CID51745296.

- ^abcOppenheimer, S. (2003).Out of Eden: The Peopling of the World.Robinson.ISBN978-1-84119-697-8.

- ^abLawler Andrew (2011). "Did Modern Humans Travel Out of Africa Via Arabia?".Science.331(6016): 387.Bibcode:2011Sci...331..387L.doi:10.1126/science.331.6016.387.PMID21273459.

- ^"Scientists discover oldest known modern human fossil outside of Africa: Analysis of fossil suggests Homo sapiens left Africa at least 50,000 years earlier than previously thought".ScienceDaily.Retrieved28 January2018.

- ^Ghosh, Pallab (2018)."Modern humans left Africa much earlier".BBC News.Retrieved28 January2018.

- ^"Jawbone fossil found in Israeli cave resets clock for modern human evolution".Retrieved28 January2018.

- ^"Earliest Modern Human Fossil Outside Africa Unearthed At Misliya Cave, Israel".Ancient Pages.27 January 2018.Retrieved28 January2018.

- ^Wallace, Ian J.; Shea, John J. (2006). "Mobility patterns and core technologies in the Middle Paleolithic of the Levant".Journal of Archaeological Science.33(9): 1293–1309.Bibcode:2006JArSc..33.1293W.doi:10.1016/j.jas.2006.01.005.

- ^Coppa, Alfredo (2005). "Newly recognized Pleistocene human teeth from Tabun Cave, Israel".Journal of Human Evolution.49(3): 301–315.doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2005.04.005.PMID15964608.Alfredo Coppa, Rainer Grün, Chris Stringer, Stephen Eggins, and Rita Vargiu Journal of Human Evolution Volume 49, Issue 3, September 2005, Pages 301-315

- ^Grun R.; Stringer C. B. (2000). "Tabun revisited: revised ESR chronology and new ESR and U-series analyses of dental material from Tabun C1".Journal of Human Evolution.39(6): 601–612.doi:10.1006/jhev.2000.0443.PMID11102271.

- ^Ewen Callaway (6 May 2010)."Neanderthal genome reveals interbreeding with humans".www.newscientist.com.Retrieved13 July2010.

- ^Soares, P; Alshamali, F; Pereira, J. B; Fernandes, V; Silva, N. M; Afonso, C; Costa, M. D; Musilova, E; MacAulay, V; Richards, M. B; Cerny, V; Pereira, L (2011)."The Expansion of mtDNA Haplogroup L3 within and out of Africa".Molecular Biology and Evolution.29(3): 915–927.doi:10.1093/molbev/msr245.PMID22096215.

- ^Posth C, Renaud G, Mittnik M, Drucker DG, Rougier H, Cupillard C, Valentin F, Thevenet C, Furtwängler A, Wißing C, Francken M, Malina M, Bolus M, Lari M, Gigli E, Capecchi G, Crevecoeur I, Beauval C, Flas D, Germonpré M, van der Plicht J, Cottiaux R, Gély B, Ronchitelli A, Wehrberger K, Grigorescu D, Svoboda J, Semal P, Caramelli D, Bocherens H, Harvati K, Conard NJ, Haak W, Powell A, Krause J (2016). "Pleistocene Mitochondrial Genomes Suggest a Single Major Dispersal of Non-Africans and a Late Glacial Population Turnover in Europe".Current Biology.26(6): 827–833.Bibcode:2016CBio...26..827P.doi:10.1016/j.cub.2016.01.037.hdl:2440/114930.PMID26853362.S2CID140098861.

- ^Vai S, Sarno S, Lari M, Luiselli D, Manzi G, Gallinaro M, Mataich S, Hübner A, Modi A, Pilli E, Tafuri MA, Caramelli D, di Lernia S (March 2019)."Ancestral mitochondrial N lineage from the Neolithic 'green' Sahara".Sci Rep.9(1): 3530.Bibcode:2019NatSR...9.3530V.doi:10.1038/s41598-019-39802-1.PMC6401177.PMID30837540.

- ^Haber M, Jones AL, Connel BA, Asan, Arciero E, Huanming Y, Thomas MG, Xue Y, Tyler-Smith C (June 2019)."A Rare Deep-Rooting D0 African Y-chromosomal Haplogroup and its Implications for the Expansion of Modern Humans Out of Africa".Genetics.212(4): 1421–1428.doi:10.1534/genetics.119.302368.PMC6707464.PMID31196864.

- ^abcdHovers, Erella;Kuhn, Steven (2007).Transitions Before the Transition: Evolution and Stability in the Middle Paleolithic and Middle Stone Age.Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 171–188.ISBN978-0-387-24661-1.Retrieved13 September2017.

- ^Mariah Vanhaeran; Francesco d'Errico; Chris Stringer; Sarah L. James; Jonathan A. Todd; Henk K. Mienis (2006)."Middle Paleolithic Shell Beads in Palestine and Algeria".Science.312(5781): (5781): 1785–1788.Bibcode:2006Sci...312.1785V.doi:10.1126/science.1128139.PMID16794076.S2CID31098527.Retrieved22 December2009.

- ^Daniella E. Bar-Yosef Mayer, 2004

- ^abBar-Yosef, Ofer (1998) "The chronology of the Middle Paleolithic of the Levant." In T. Akazawa, K. Aoki, and O. Bar-Yosef, eds.Neandertals and modern humans in Western Asia.New York: Plenum Press. pp. 39–56.

- ^Valladas, Helene, Norbert Mercier, Jean-Louis Joron, and Jean-Louis Reyss (1998) "Gif Laboratory dates for Middle Paleolithic Levant." In T. Akazawa, K. Aoki, and O. Bar-Yosef, eds.Neandertals and modern humans in Western Asia.New York: Plenum Press. pp. 69–75.

- ^McHenry, H."Skhūl".Britannica, academic version.Encyclopædia Britannica.Retrieved9 July2014.

- ^abcBernard Vandermeersch, The excavation of Qafzeh, Bulletin du Centre de recherche français de Jérusalem, retrieved 12 July 2010.http://bcrfj.revues.org/index1192.html

- ^abcdBar-Yosef Mayer, Daniella E.; Vandermeersch, Bernard; Bar-Yosef, Ofer (2009). "Shells and ochre in Middle Paleolithic Qafzeh Cave, Palestine: indications for modern behavior".Journal of Human Evolution.56(3): 307–314.doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2008.10.005.PMID19285591.

- ^abJabel Qafzehhttp://www.mnsu.edu/emuseum/archaeology/sites/middle_east/jabel_qafzeh.htmArchived4 June 2010 at theWayback Machine)

- ^abBrief communication: An early case of hydrocephalus: The Middle Paleolithic Qafzeh 12 child (Palestine) Anne-Marie Tillier, Baruch Arensburg, Henri Duday, Bernard Vandermeersch (2000)http://www3.interscience.wiley.com/journal/76510952/abstract?CRETRY=1&SRETRY=0Archived5 January 2013 atarchive.today

- ^Coutinho-Nogueira, Dany; Coqueugniot, Hélène; Tillier, Anne-marie (10 September 2021)."Qafzeh 9 Early Modern Human from Southwest Asia: age at death and sex estimation re-assessed".HOMO.72(4): 293–305.doi:10.1127/homo/2021/1513.PMID34505621.S2CID237469414.

- ^Cartmill, M., Smith, F.H. and Brown, K.B. (2009).The Human Lineage.

- ^Coutinho Nogueira, D.; Dutour, O.; Coqueugniot, H.; Tillier, A. -m. (1 September 2019)."Qafzeh 9 mandible (ca 90–100 kyrs BP, Israel) revisited: μ-CT and 3D reveal new pathological conditions"(PDF).International Journal of Paleopathology.26:104–110.doi:10.1016/j.ijpp.2019.06.002.PMID31351220.S2CID198953011.

- ^Perikymata number and spacing on early modern human teeth: evidence from Qafzeh cave, Palestine J. M. Monge, A.-m. Tillier & A. E. Mann

- ^Schuh, Alexandra; Dutailly, Bruno; Coutinho Nogueira, Dany; Santos, Frédéric; Arensburg, Baruch; Vandermeersch, Bernard; Coqueugniot, Hélène; Tillier, Anne-Marie (2017)."La mandibule de l'adulte Qafzeh 25 (Paléolithique moyen), Basse Galilée. Reconstruction virtuelle 3D et analyse morphométrique"(PDF).Paléorient.43(1): 49–59.doi:10.3406/paleo.2017.5751.S2CID164499671.

- ^Coutinho Nogueira, Dany (2019).Paléoimagerie appliquée aux Homo sapiens de Qafzeh (Paléolithique moyen, Levant sud). Variabilité normale et pathologique.Paris: Thesis of Ecole Pratique des Hautes Etudes, PSL University. p. 201.

- ^Coutinho-Nogueira, Dany; Coqueugniot, Hélène; Santos, Frédéric; Tillier, Anne-marie (20 August 2021)."The bony labyrinth of Qafzeh 25 Homo sapiens from Israel"(PDF).Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences.13(9): 151.Bibcode:2021ArAnS..13..151C.doi:10.1007/s12520-021-01377-2.ISSN1866-9557.S2CID237219305.