Spring and Autumn period

| Spring and Autumn period | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | Xuân thuThời đại | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | Xuân thuThời đại | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hanyu Pinyin | Chūnqiū shídài | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Part ofa serieson the |

| History of China |

|---|

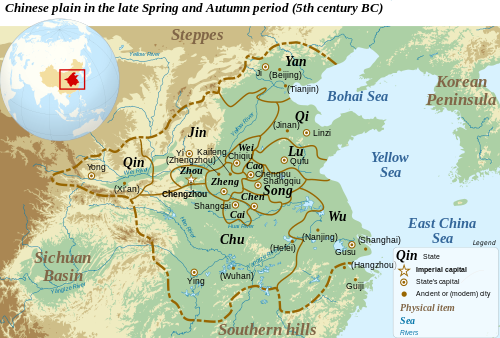

TheSpring and Autumn periodinChinese historylasted approximately from 770 to 481 BCE[1][a]which corresponds roughly to the first half of theEastern Zhouperiod. The period's name[b]derives from theSpring and Autumn Annals,a chronicle of the state ofLubetween 722 and 481 BCE, which tradition associates withConfucius(551–479 BCE). During this period, royal control over the various local polities eroded as regional lords increasingly exercised political autonomy, negotiating their own alliances, waging wars amongst themselves, up to defying the king's court inLuoyi.The gradualPartition of Jin,one of the most powerful states, is generally considered to mark the end of the Spring and Autumn period and the beginning of theWarring States period.

Background[edit]

In 771 BCE, aQuanronginvasion in coalition with the states ofZengandShen—the latter polity being the fief ofthe grandfatherof the disinherited crown princeYijiu—destroyed theWestern ZhoucapitalHaojing,killingKing Youand establishing Yijiu as king at the eastern capitalLuoyi(Lạc ấp).[9]The event ushered in the Eastern Zhou dynasty, which is divided into the Spring and Autumn and theWarring Statesperiods. During the Spring and Autumn period, China'sfeudalsystem offengjian( phong kiến ) became largely irrelevant. The Zhou court, having lost its homeland in theGuanzhongregion, held nominal power, but had real control over only a small royaldemesnecentered on Luoyi. During the early part of the Zhou dynasty period, royal relatives and generals had been given control over fiefdoms in an effort to maintain Zhou authority over vast territory.[10]As the power of the Zhou kings waned, these fiefdoms became increasingly independentstates.

The most important states (known later as the twelve vassals) came together in regular conferences where they decided important matters, such as military expeditions against foreign groups or against offending nobles. During these conferences one vassal ruler was sometimes declaredhegemon(Chinese:Bá;pinyin:bó;later, Chinese:Bá;pinyin:bà).

As the era continued, larger and more powerful states annexed or claimedsuzeraintyover smaller ones. By the 6th century BCE most small states had disappeared and just a few large and powerful principalities dominated China. Some southern states, such as Chu andWu,claimed independence from the Zhou, who undertook wars against some of them (Wu andYue).

Amid the interstate power struggles, internal conflict was also rife: six élite landholding families waged war on each other inside Jin, political enemies set about eliminating the Chen family in Qi, and the legitimacy of the rulers was often challenged in civil wars by various royal family members in Qin and Chu. Once all these powerful rulers had firmly established themselves within their respective dominions, the bloodshed focused more fully on interstate conflict in theWarring States period,which began in 403 BCE when the three remaining élite families in Jin—Zhao, Wei, and Han—partitioned the state.

Early Spring and Autumn (771–685 BCE)[edit]

Court moves east (771)[edit]

After the Zhou capital was sacked by theMarquess of Shenand theQuanrongbarbarians,the Zhou moved the capital east from the now desolatedZongzhouinHaojingnear modernXi'antoWangchengin theYellow RiverValley. The Zhou royalty was then closer to its main supporters,[11]particularly Jin, andZheng;[12][13]the Zhou royal family had much weaker authority and relied on lords from these vassal states for protection, especially during their flight to the eastern capital. In Chengzhou, Prince Yijiu was crowned by his supporters asKing Ping.[13]However, with the Zhou domain greatly reduced to Chengzhou and nearby areas, the court could no longer support the six army groups it had in the past; Zhou kings had to request help from powerful vassal states for protection from raids and for resolution of internal power struggles. The Zhou court would never regain its original authority; instead, it was relegated to being merely a figurehead of the regional states and ritual leader of theJi clanancestral temple. Though the king retained theMandate of Heaven,the title held little actual power.

With the decline of Zhou power, the Yellow River drainage basin was divided into hundreds of small, autonomous states, most of them consisting of a single city, though a handful of multi-city states, particularly those on the periphery, had power and opportunity to expand outward.[14]A total of 148 states are mentioned in the chronicles for this period,[c]128 of which were absorbed by the four largest states by the end of the period.[16]

Shortly after the royal court's move to Chengzhou, a hierarchical alliance system arose where the Zhou king would give the title of hegemon (Bá) to the leader of the state with the most powerful military; the hegemon was obligated to protect both the weaker Zhou states and the Zhou royalty from the intruding non-Zhou peoples:[17][18]theNorthern Di,theSouthern Man,theEastern Yi,and theWestern Rong.This political framework retained thefēngjiànpower structure, though interstate and intrastate conflict often led to declining regard forclan customs,respect for the Ji family, and solidarity with other Zhou peoples.[19]The king's prestige legitimized the military leaders of the states, and helped mobilize collective defense of Zhou territory against "barbarians".[20]

Over the next two centuries, the four most powerful states—Qin,Jin,QiandChu—struggled for power. These multi-city states often used the pretext of aid and protection to intervene and gain suzerainty over the smaller states. During this rapid expansion,[21]interstate relations alternated between low-level warfare and complex diplomacy.[22]

Zheng falls out with the court (722–685)[edit]

Duke Yin of Luascended the throne in 722.[23]From this year on, the state ofLukept an official chronicle, theSpring and Autumn Annals,which along with its commentaries is the standard source for the Spring and Autumn period. Corresponding chronicles are known to have existed in other states as well, but all but the Lu chronicle have beenlost.

In 717,Duke Zhuang of Zhengwent to the capital for an audience withKing Huan.During the encounter the duke felt he was not treated with the respect and etiquette which would have been appropriate, given that Zheng was now the chief protector of the capital.[23]In 715, Zheng also became involved in a border dispute with Lu regarding the Fields of Xu. The fields had been put in the care of Lu by the king for the exclusive purpose of producing royal sacrifices for the sacredMount Tai.[23]For Zheng to regard the fields as just any other piece of land was an insult to the court.

By 707, relations had soured enough that the king launched a punitive expedition against Zheng. The duke counterattacked and raided Zhou territory, defeating the royal forces in theBattle of Xugeand injuring the king himself.[16][23][24]Zheng was the first vassal to openly defy the king, kicking off the centuries of warfare without respect for the old traditions which would characterize the period.

The display of Zheng's martial strength was effective until succession problems after Zhuang's death in 701 weakened the state.[12]

In 692, there was a failed assassination attempt againstKing Zhuang,orchestrated by elements at court.[23]

The Five Hegemons (685–591 BCE)[edit]

Hegemony of Qi (685–643)[edit]

The first hegemon wasDuke Huan of Qi(r. 685–643). With the help of his prime minister,Guan Zhong,Duke Huan reformed Qi to centralize its power structure. The state consisted of 15 "townships"(Huyện) with the duke and two senior ministers each in charge of five; military functions were also united with civil ones. These and related reforms provided the state, already powerful from control of trade crossroads, with a greater ability to mobilize resources than the more loosely organized states.[25]

By 667, Qi had clearly shown its economic and military predominance, and Duke Huan assembled the leaders ofLu,Song,Chen,andZheng,who elected him as their leader. Soon after,King Hui of Zhouconferred the title ofbà(hegemon), giving Duke Huan royal authority in military ventures.[26][27]An important basis for justifying Qi's dominance over the other states was presented in the slogan 'Revere the King, Expel the Barbarians' (Tôn vương nhương di;zun wang rang yi). The role of subsequent hegemons would also be framed in this way: as the primary defender and supporter of nominal Zhou authority and the existing order. Using this authority, during the first eleven years of his hegemony, Duke Huan intervened in a power struggle in Lu; protectedYanfrom encroachingWestern Rongnomads; drove offNorthern Dinomads after their invasions ofWeyandXing,providing the people with provisions and protective garrison units; and led an alliance of eight states to conquerCaiand thereby block the northward expansion ofChu.[28]

At his death in 643, five of Duke Huan's sonscontended for the throne,badly weakening the state so that it was no longer regarded as the hegemon. For nearly ten years, no ruler held the title.[29]

Hegemony of Song (643–637)[edit]

Duke Xiang of Songattempted to claim the hegemony in the wake of Qi's decline, perhaps driven by a desire to restore theShang dynastyfrom which Song had descended. He hosted peace conferences in the same style as Qi had done, and conducted aggressive military campaigns against his rivals. Duke Xiang's ambitions met their end when, against the advice of his staff, he attacked the much larger state of Chu. The Song forces were defeated at the battle of Hong (Hoằng) in 638, and the duke himself died in the following year from an injury sustained in the battle. After Xiang's death his successors adopted a more modest foreign policy, better suited to the country's small size.[30]

As Duke Xiang was never officially recognized as hegemon by the King of Zhou, not all sources list him as one of the Five Hegemons.

Hegemony of Jin (636–628)[edit]

WhenDuke Wen of Jincame to power in 636 after extensive peregrinations in exile, he capitalized on the reforms of his father,Duke Xian(r. 676–651), who had centralized the state, killed off relatives who might threaten his authority, conquered sixteen smaller states, and even absorbed some Rong and Di peoples to make Jin much more powerful than it had been previously.[31]When he assistedKing Xiangin a succession struggle in 635, the king awarded Jin with strategically valuable territory near Chengzhou.

Duke Wen then used his growing power to coordinate a military response with Qi, Qin, and Song against Chu, which had begun encroaching northward after the death of Duke Huán of Qi. With a decisive Chu loss at theBattle of Chengpuin 632, Duke Wen's loyalty to the Zhou king was rewarded at an interstate conference when King Xīang awarded him the title ofbà.[29]

After the death of Duke Wen in 628, a growing tension manifested in interstate violence that turned smaller states, particularly those at the border between Jin and Chu, into sites of constant warfare; Qi and Qin also engaged in numerous interstate skirmishes with Jin or its allies to boost their own power.[32]

Hegemony of Qin (628–621)[edit]

Duke Mu of Qinhad ascended the throne in 659 and forged an alliance with Jin by marrying his daughter to Duke Wen. In 624, he established hegemony over the western Rong barbarians and became the most powerful lord of the time. However he did not chair any alliance with other states nor was he officially recognized as hegemon by the king. Therefore, not all sources accept him as one of the Five Hegemons.

Hegemony of Chu (613–591)[edit]

King Zhuang of Chuexpanded the borders of Chu well north of theYangtzeRiver, threatening the Central States in modernHenan.At one point the Chu forces advanced to just outside the royal capital of Chengzhou, upon which King Zhuang sent a messenger to inquire into the heft and bulk of theNine Cauldrons– the symbols of royal ritual authority – implying he might soon arrange to have them moved to his own capital. In the end the Zhou capital was spared, and Chu shifted focus to harassing the nearby state of Zheng. The once-hegemon state of Jin intervened to rescue Zheng from the Chu invaders but were resolutely defeated, which marks the ascension of Chu as the dominant state of the time.[33]

Despite hisde factohegemony, King Zhuang's self-proclaimed title of "king" was never recognized by the Zhou states. In theSpring and Autumn Annalshe is defiantly referred to asZi(Tử,ruler; unratified lord),[34]even at a time when he dominated most of south China. Later historians however always include him as one of the Five Hegemons.

Late Spring and Autumn (591–453 BCE)[edit]

The Six Ministers (588)[edit]

In addition to interstate conflict, internal conflicts between state leaders and local aristocrats also occurred. Eventually the dukes of Lu, Jin, Zheng, Wey and Qi would all become figureheads to powerful aristocratic families.[35]

In the case of Jin, the shift happened in 588 when the army was split into six independent divisions, each dominated by a separate noble family: Zhi ( trí ), Zhao ( triệu ), Han ( hàn ), Wei ( ngụy ), Fan ( phạm ), and Zhonghang ( trung hành ). The heads of the six families were conferred the titles of viscounts and made ministers,[36]each heading one of the six departments of Zhou dynasty government.[37]From this point on, historians refer to "The Six Ministers" as the true power brokers of Jin.

The same happened to Lu in 562, when theThree Huandivided the army into three parts and established their own separate spheres of influence. The heads of the three families were always among the department heads of Lu.

Rise of Wu (584)[edit]

Wuwas a state in modernJiangsuoutside the Zhou cultural sphere, considered "barbarian", where the inhabitants sported short hair and tattoos and spoke an unintelligible language.[38][39]Although its ruling house claimed to be a senior lineage in theJiancestral temple,[d]Wu did not participate in the politics and wars of China until the last third of the Spring and Autumn period.

Their first documented interaction with the Spring and Autumn states was in 584, when a Wu force attacked the small border state of Tan (Đàm) causing some alarm in the various Chinese courts. Jin was quick to dispatch an ambassador to the court of the Wu king,Shoumeng.Jin promised to supply Wu with modern military technology and training in exchange for an alliance against Chu, a neighbour of Wu and Jin's nemesis in the struggle for hegemony. King Shoumeng accepted the offer, and Wu would continue to harass Chu for years to come.[41]

Attempts at peace (579)[edit]

After a period of increasingly exhausting warfare, Qi, Qin, Jin and Chu met at a disarmament conference in 579 and agreed to declare a truce to limit their military strength.[42]This peace did not last very long and it soon became apparent that thebàrole had become outdated; the four major states had each acquired their own spheres of control and the notion of protecting Zhou territory had become less cogent as the control over (and the resulting cultural assimilation of) non-Zhou peoples, as well as Chu's control of some Zhou areas, further blurred an already vague distinction between Zhou and non-Zhou.[43]

In addition, new aristocratic houses were founded with loyalties to powerful states, rather than directly to the Zhou kings, though this process slowed down by the end of the seventh century, possibly because territory available for expansion had been largely exhausted.[43]The Zhou kings had also lost much of their prestige[35]so that, when Duke Dao of Jin (r. 572–558) was recognized asbà,it carried much less meaning than it had before.

Hegemony of Wu (506–496)[edit]

In 506,King Helüascended the throne of Wu. With the help ofWu ZixuandSun Tzu,[44]the author ofThe Art of War,he launched major offensives against the state of Chu. They prevailed in five battles, one of which was the Battle of Boju, and conquered the capital Ying. However, Chu managed to ask the state of Qin for help, and after being defeated by Qin, the vanguard general of Wu troops, Fugai, a younger brother of Helü, led a rebellion. After beating Fugai, Helü was forced to leave Chu. Fugai later retired to Chu and settled there.King Helüdied during an invasion of Yue in 496. Some sources list him as one of theFive Hegemons.[who?]

He was succeeded by his sonKing Fuchai of Wu,who nearly destroyed the Yue state, imprisoningKing Goujian of Yue.Subsequently, Fuchai defeated Qi and extended Wu influence into central China.

In 499, the philosopherConfuciuswas made acting prime minister of Lu. He is traditionally (if improbably) considered the author or editor of theSpring and Autumn annals,from which much of the information for this period is drawn. After only two years he was forced to resign and spent many years wandering between different states before returning to Lu. After returning to Lu he did not resume a political career, preferring to teach. Tradition holds that it was in this time he edited or wrote theFive Classics,including theSpring and Autumn Annals.

Hegemony of Yue (496–465)[edit]

In 482,King Fuchai of Wuheld an interstate conference to solidify his power base, but Yue captured the Wu capital. Fuchai rushed back but was besieged and died when the city fell in 473. Yue then concentrated on weaker neighbouring states, rather than the great powers to the north.[45]With help from Wu's enemy Chu, Yue was able to be victorious after several decades of conflict. King Goujian destroyed and annexed Wu in 473, after which he was recognized as hegemon.

TheZuozhuan,Guoyu,andShijiprovide almost no information about Goujian's subsequent reign or policies. What little is said is told from the perspective of other states, such as Duke Ai of Lu trying to enlist Yue's help in a coup against the Three Huan. Sima Qian notes that Goujian reigned on until his death, and that afterwards his descendants—for whom no biographical information is given—continued to rule for six generations before the state was finally absorbed into Chu during theWarring States period.

Partition of Jin[edit]

After the great age of Jin power, the Jin rulers began to lose authority over their ministerial lineages. A full-scale civil war between 497 and 453 ended with the elimination of most noble lines; the remaining aristocratic families divided Jin into three successor states:Han,Wei,andZhao.[45]This is the last event recorded in theZuozhuan.

With the absorption of most of the smaller states in the era, this partitioning left seven major states in the Zhou world: the three fragments of Jin, the three remaining great powers of Qin, Chu and Qi, and the weaker state ofYan(Yến) near modern Beijing. The partition of Jin, along with theUsurpation of Qi by Tian,marks the beginning of theWarring States period.

Interstate relations[edit]

Ancient sources such as theZuo Zhuanand the eponymousChunqiurecord the various diplomatic activities, such as court visits paid by one ruler to another (Triều;cháo), meetings of officials or nobles of different states (Hội;Hội;huì), missions of friendly inquiries sent by the ruler of one state to another (Sính;pìn), emissaries sent from one state to another (Sử;shǐ), and hunting parties attended by representatives of different states (Thú;shou).

Because of Chu's non-Zhou origin, the state was considered semi-barbarian and its rulers—beginning withKing Wuin 704 BCE—proclaimed themselves kings in their own right. Chu intrusion into Zhou territory was checked several times by the other states, particularly in the major battles ofChengpu(632 BCE),Bi(595 BCE) andYanling(575 BCE), which restored the states ofChenandCai.

Literature[edit]

Some version of theFive Classicsexisted in Spring and Autumn period, as characters in theZuozhuanandAnalectsfrequently quote theBook of PoetryandBook of Documents.On the other hand, theZuozhuandepicts some characters actuallycomposingpoems that would later be included in the received text of theBook of Poetry.[which?]In theAnalectsthere are frequent references to "The Rites",[46]but as Classical Chinese does not employ punctuation or any markup to distinguish book titles from regular nouns it is not possible to know if what is meant is theEtiquette and Ceremonial(known then as theBook of Rites) or just the concept of ritual in general. On the other hand, the existence of theBook of Changesis well-attested in theZuozhuan,as multiple characters use it for divination and accurately quote the received text.

Sima Qianclaims that it was Confucius who, towards the close of the Spring and Autumn period, edited the received versions of theBook of Poetry,Book of Documents,andBook of Rites;wrote the "Ten Wings" commentary on theBook of Changes;and wrote the entirety of theSpring and Autumn Annals.[47]This was long the predominant opinion in China, but modern scholarship considers it unlikely that all five classics could be the product of one man. The transmitted versions of these works all derive from the versions edited byLiu Xinin the century following Sima Qian.

While many philosophers such asLao TzuandSun Tzuwere active in the Spring and Autumn period, their ideas were probably not put into writing until the following Warring States period.

Aristocracy[edit]

While the aristocracy of theWestern Zhoufrequently interacted via the medium of the royal court, the collapse of central power at the end of the first half of the dynasty left in its wake hundreds of autonomous polities varying drastically in size and resources, nominally connected by bonds of cultural and ritual affiliation increasingly attenuated by the passage of time. Whole lineage groups moved around under socioeconomic stress, border groups not associated with the Zhou culture gained in power and sophistication, and the geopolitical situation demanded increased contact and communication.[48]

Under this new regime, an emergent systematization of noble ranks took root. Where the Western Zhou had concerned itself with politics, the ancestral temples, and legitimacy, in the Eastern Zhou politics came to the fore.[49]Titles which had previously reflected lineage seniority took on purely political meanings. At the top of the bunch wereGong(Công) andHou(Hầu), favoured lineages of old with generally larger territories and greater resources and prestige at their disposal. The majority of rulers were of the middling but tiered gradesBo(Bá) andZi(Tử). The rulers of two polities maintained the titleNan(Nam). A 2012 survey found no difference in grade betweenGongandHou,or betweenZiandNan.[50]Meanwhile, a new class of lower-tier aristocrats formed: theShi(Sĩ), gentlemen too distantly related to the great houses to be born into a life of wielding power, but still part of the elite culture, aiming at upward social mobility, typically through the vector of officialdom.

One individual well attested in the process of fixing the ranks of rulers into a coherent scheme wasZichanofZheng,who both submitted a memorial to the king of Chu informing him of the proposed new system in 538 BCE, and argued at a 529 BCE interstate conference that tributes should be graded based on rank, given the disparity in available resources.[51]

Alongside this development, there was precedent of Zhou kings "upgrading" noble ranks as a reward for service to the throne, giving the recipients a bit more diplomatic prestige without costing the royal house any land.[52]During the decline of the royal house, although real power was wrested from their grasp, their divine legitimacy was not brought into question, and even with the king reduced to something of a figurehead, his prestige remained supreme as Heaven's eldest son.[53]

Archaeologically excavated primary sources and received literature agree to a high degree of systematization and stability in noble titles during the Eastern Zhou, indicating an actual historical process. A 2007 survey of bronze inscriptions from 31 states found only eight polities whose rulers used varying titles of nobility to describe themselves.[54]

Important figures[edit]

The Five Hegemons( xuân thu ngũ bá ): With the royal house of Zhou lacking the military strength to defend itself, and with the various states experiencing tension and conflict, certain very powerful lords took the position of hegemon, ostensibly to uphold the house of Zhou and maintain the peace to the degree possible. They paid tribute to the royal court, and were owed tribute by the other rulers. Traditional history lists five hegemons during the Spring and Autumn period:[55]

- Duke Huan of Qi(r. 685–643 BCE)

- Duke Xiang of Song(r. 650–637 BCE)

- Duke Wen of Jin(r. 636–628 BCE)

- Duke Mu of Qin(r. 659–621 BCE)

- King Zhuang of Chu(r. 613–591 BCE)

Alternatively:[citation needed]

- Duke Huan of Qi(r. 685–643 BCE)

- Duke Wen of Jin(r. 636–628 BCE)

- King Zhuang of Chu(r. 613–591 BCE)

- King Fuchai of Wu(r. 495–473 BCE)

- King Goujian of Yue(r. 496–465 BCE)

Bureaucrats or Officers

- Guan Zhong,advisor of Duke Huan of Qi

- Baili Xi,prime minister of Qin

- Wu Zixu,Duke of Shen, important adviser of KingHelü,early culture hero,[44]sometimes considered "the single best recorded individual in the history of the Spring and Autumn period"[56]

- Bo Pi,bureaucrat under KingHelüwho played an important diplomatic role in Wu–Yue relations

- Wen Zhong,advisor ofKing Goujian of Yuein his war against Wu

- Fan Li,another advisor to Goujian, also renowned for his incredible business acumen

- Zichan,leader of self-strengthening movements inZheng

- Yan YingorYanzi,central figure of theYanzi Chunqiu

Influential scholars

- ConfuciusorKongzi,leading figure inConfucianism

- Lao-tseorLaozi,teacher ofTaoism

- Mo Di,Mozi,orMo-tse,founder ofMohism

- Sun TzuorSunzi,author ofThe Art of War

Other people

- Lu Ban,master builder

- Yao Li,sent by King Helü to killQing Ji

- Zhuan Zhu,sent by Helü to kill his cousin King Liao

- Bo Ya,outstanding musician

- Ou Yezi,swordsmaker

List of states[edit]

TheLijiclaims that the Eastern Zhou was divided into 1773states,[15]of which 148 are known by name.[16]

| Name | Chinese | Capital | Location[57] | Established | Dissolved |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ba | Ba | Yicheng ( di thành ) | Changyang County,Hubei | King Wu's reign | 316 BCE: to Qin |

| Pingdu ( bình đô ) | Fengdu County,Chongqing | ||||

| Zhi ( chỉ ) | Fuling District,Chongqing | ||||

| Jiangzhou ( giang châu ) | Chongqing | ||||

| Dianjiang ( điếm giang ) | Hechuan District,Chongqing | ||||

| Langzhong ( lãng trung ) | Langzhong,Sichuan | ||||

| Bi | Tất | Bi | unknown | King Wu's reign | unknown |

| Biyang, Fuyang | Bức dươngorPhó dương | Biyang | Yicheng District, Zaozhuang,Shandong | unknown | 563 BCE: to Song |

| Cai | Thái | Shangcai ( thượng thái ) | Shangcai County,Henan | King Wu's reign | 447 BCE: to Chu |

| Xincai ( tân thái ) | Xincai County,Henan | ||||

| Xiacai ( hạ thái ) | Fengtai County,Anhui | ||||

| Cao | Tào | Taoqiu ( đào khâu ) | Dingtao District,Heze,Shandong | King Wu's reign | 487 BCE: to Song |

| Chao | Sào | Chao | Chaohu,Anhui | unknown | c. 518 BCE:to Wu |

| Chen | Trần | Wanqiu ( uyển khâu ) | Huaiyang District,Zhoukou,Henan | King Wu's reign | 479 BCE: to Chu |

| Cheng | ThànhorThành | Cheng | Ningyang County,Shandong | King Wu's reign | 408 BCE: to Qi |

| Chu | SởorKinh | Danyang( đan dương ) | Xichuan County,Henan | King Cheng's reign | 223 BCE: to Qin |

| Ying( dĩnh ) | Jingzhou,Hubei | ||||

| Chen ( trần ) | Huaiyang District, Zhoukou, Henan | ||||

| Shouchun ( thọ xuân ) | Shou County,Anhui | ||||

| Chunyu, Zhou | Thuần vuorChâu | Zhou ( châu ) | Anqiu,Shandong | King Wu's reign | 706 BCE: to Qi ( kỷ ) |

| Dai | Đái | Dai | Minquan County,Henan | unknown | 713 BCE: to Zheng |

| Dao | Đạo | Dao | unknown | unknown | unknown |

| Deng | Đặng | Deng | Dengzhou,Henan | before Western Zhou | 678 BCE: to Chu |

| E | Ngạc | E | Nanyang, Henan | before Western Zhou | 863 BCE: to Chu |

| Fan | PhiênorPhanorBà | Fan | Gushi County,Henan | unknown | 504 BCE: to Wu |

| Fan | Phàm | Fan | Huixian,Henan | unknown | unknown |

| Fan | Phàn | Fan | Chang'an District, Xi'an,Shaanxi | King Xuan's reign | 635 BCE: to Jin |

| Yang ( dương ) | Jiyuan,Henan | ||||

| Gan | Cam | Gan | Yuanyang County, Henan | King Xiang's reign | unknown |

| Gao | Cáo | Gao | Chengwu County,Shandong | King Wu's reign | 8th century BCE: to Song |

| Ge | Cát | Ge | Ningling County,Henan | before Western Zhou | unknown |

| Gong | Củng | Gong | Xiaoyi,Henan | unknown | 516 BCE: to Jin |

| Gong | Cộng | Gong | Huixian, Henan | unknown | mid-7th century BCE: to Wey |

| Guang | Quang | Guang | Guangshan County,Henan | before Western Zhou | 650 BCE: to Chu |

| Guo | Quách | Guo | Liaocheng,Shandong | unknown | 670 BCE: to Qi |

| Eastern Guo | Đông quắc | Zhi ( chế ) | Xingyang,Henan | King Wu's reign | 767 BCE: to Zheng |

| Western Guo | Tây quắc | Yongdi ( ung địa ) | Baoji,Shaanxi | King Wu's reign | 687 BCE: to Jin |

| Shangyang ( thượng dương ) | Shan County, Henan | ||||

| Hu | Hồ | Hu | Wuyang County,Henan | unknown | 763 BCE: to Zheng |

| Hua | Hoạt | Hua | Minquan County, Henan | unknown | 627 BCE: to Qin |

| Fei ( phí ) | Yanshi,Henan | ||||

| Huang | Hoàng | Longgu Xiang | Huangchuan County, Henan | unknown | 648 BCE: to Chu |

| Hui | 鄶orHộiorCối | Hui | Xinzheng,Henan | unknown | 769 BCE: to Zheng |

| Ji | Kỷ | Ji | Shouguang,Shandong | unknown | 690 BCE: to Qi |

| Ji | Cực | Ji | Shan County, Shandong | unknown | 721 BCE: to Lu |

| Ji | Tế | Ji | Changyuan,Henan | King Wu's reign | 750 BCE: to Zheng |

| Guan ( quản ) | Zhengzhou,Henan | ||||

| Jiang | Giang | Jiang (Chinese:Giang) | Xi County, Henan | 1101 BCE | 623 BCE: to Chu |

| Jiang | Tưởng | Jiang | Gushi County,Henan | King Cheng's reign | 617 BCE: to Chu |

| Jie | Giới | Jie | Jiaozhou,Shandong | unknown | unknown:to Qi |

| Jin | Tấn | Tang ( đường ), or Jin | Yicheng County,Shanxi | King Cheng's reign | 376 BCE: toHanandZhao |

| Quwo ( khúc ốc ) | Wenxi County,Shanxi | ||||

| Jiang ( thao ), or Yi ( dực ) | Yicheng County,Shanxi | ||||

| Xintian ( tân điền ), or Xinjiang ( tân thao ) | Houma,Shanxi | ||||

| Ju | Cử | Jiegen ( giới căn ) | Jiaozhou,Shandong | King Wu's reign | 431 BCE: to Chu |

| Ju | Ju County,Shandong | ||||

| Lai | Lai | Changle ( xương nhạc ) | Changle County,Shandong | before Western Zhou | 567 BCE: to Qi |

| Lan | Lạm | Lan | Tengzhou,Shandong | 781 BCE | 521 BCE: to Lu |

| Liang | Lương | Liang | Hancheng,Shaanxi | unknown | 641 BCE: to Qin |

| Liao,Miu | LiễuorMâu | Liao | Gushi County,Henan | unknown | 622 BCE: to Chu |

| Liu | Lưu | Liu | Yanshi,Henan | 592 BCE | c. 5th century BCE:to Zhou dynasty |

| Lu | Lỗ | Lu | Lushan County, Henan | King Cheng's reign | 256 BCE: to Chu |

| Yancheng ( yểm thành ) | Qufu,Shandong | ||||

| Qufu ( khúc phụ ) | Qufu, Shandong | ||||

| Lü | Lữ | Lü | Nanyang, Henan | unknown' | 688 BCE: to Chu |

| Mao | Mao | Mao | Qishan County,Shaanxi | King Wu's reign | 516 BCE: to Qin |

| Mao | Mao | Mao | Jinxiang County,Shandong | King Cheng's reign | 6th century BCE: to Zou |

| Ni,Xiaozhu | 郳orTiểu chu | Ni | Shanting District,Zaozhuang, Shandong | King Cheng's reign | 335 BCE: to Chu |

| Qi | Tề | Yingqiu ( doanh khâu ), orLinzi( lâm tri ) | Linzi District,Zibo,Shandong | King Wu's reign | 221 BCE: to Qin |

| Qi | Kỷ | Qi | Qi County,Henan | before Western Zhou | 445 BCE: to Chu |

| Pingyang ( bình dương ) | Xintai,Shandong | ||||

| Yuanling ( duyên lăng ) | Changle County, Shandong | ||||

| Chunyu ( thuần vu ) | Anqiu, Shandong | ||||

| Qin | Tần | Qin | Qingshui County,Gansu | King Xiao's reign | 206 BCE: to Western Chu |

| Qian ( khiên ) | Long County, Shaanxi | ||||

| Pingyang ( bình dương ) | Mei County, Shaanxi | ||||

| Yong ( ung ) | Fengxiang County,Shaanxi | ||||

| Yueyang( lịch dương ) | Yanliang District,Xi'an, Shaanxi | ||||

| Xianyang( hàm dương ) | Xianyang, Shaanxi | ||||

| Quan | Quyền | Quan | Jingmen,Hubei | unknown | 704 BCE: to Chu |

| Ren | Nhậm | Ren | Weishan County,Shandong | unknown | Warring States period |

| Ruo | Nhược | Shangruo ( thượng nhược ) or Shangmi ( thương mật ) | Xichuan County,Henan | unknown | unknown |

| Xiaruo ( hạ nhược ) | Yicheng, Hubei | ||||

| Shao | TriệuorThiệu | Shao | Qishan County,Shaanxi | King Wu's reign | 513 BCE: to Zhou dynasty |

| Shan, Tan | ĐanorĐàn | Shan | Mengjin County, Henan | King Cheng's reign | unknown |

| Shen,Xie | ThânorTạ | Shen | Nanyang, Henan | King Xuan's reign | 688 – 680 BCE: to Chu |

| Shen | Thẩm | Shen | Linquan County,Anhui | King Cheng's reign | 506 BCE: to Cai |

| Shu | Thục | unknown | unknown | unknown | 316 BCE: to Qin |

| Song | Tống | Shangqiu ( thương khâu ) | Shangqiu,Henan | King Cheng's reign | 286 BCE: to Qi |

| Su | Túc | Su | Dongping County,Shandong | unknown | 7th century BCE: to Song |

| Sui | Toại | Sui | Ningyang County,Shandong | before Western Zhou | 681 BCE: to Qi |

| Tan | Đàm | Tan | Tancheng County,Shandong | unknown | 414 BCE: to Yue |

| Tan | Đàm | Tan | Zhangqiu,Shandong | c. 1046 BCE | 684 BCE: to Qi |

| Teng | Đằng | Teng | Teng County,Shandong | King Wu's reign | 297 BCE: to Song |

| Wangshu | Vương thúc | Wangshu | Mengjin County,Henan | King Xiang of Zhou | 563 BCE: to Zhou dynasty |

| Wei (Wey) | Vệ | Zhaoge( triều ca ) | Qi County,Henan | King Cheng's reign | 209 BCE: to Qin |

| Cao ( tào ) | Hua County, Henan | ||||

| Chuqiu ( sở khâu ) | Hua County, Henan | ||||

| Diqiu ( đế khâu ) | Puyang County,Henan | ||||

| Yewang ( dã vương ) | Qinyang,Henan | ||||

| Wen | Ôn | Wen | Wen County, Henan | King Wu's reign | 650 BCE: toBeidi |

| Wu | Ngô | Wu, or Gusu ( cô tô ) | Suzhou,Jiangsu | unknown | 473 BCE: to Yue |

| Xi | Tức | Xi | Xi County, Henan | unknown | 684 – 680 BCE: to Chu |

| Xian | Huyền | Xian | Huanggang,Hubei | unknown | 655 BCE: to Chu |

| Xiang | Hướng | Xiang | Ju County,Shandong | unknown | 721 BCE: to Ju |

| Hình | Xingtai,Hebei | King Cheng's reign | 632 BCE: to Wey | ||

| Yiyi ( di nghi ) | Liaocheng,Shandong | ||||

| Xu | Từ | Xu | Tancheng County,Shandong | before Western Zhou | 512 BCE: to Wu |

| Xu | HứaorHứa | Xu | Xuchang,Henan | King Wu's reign | c. 5th century BCE:to Chu |

| Ye ( diệp ) | Ye County,Henan | ||||

| Yi ( di ) or Chengfu ( thành phụ ) | Bozhou,Anhui | ||||

| Xi ( tích ) | Xixia County,Henan | ||||

| Rongcheng ( dung thành ) | Lushan County, Henan | ||||

| Xue,Pi | TiếtorBi | Xue | Tengzhou,Shandong | before Western Zhou | 418 BCE: to Qi |

| Xiapi ( hạ bi ) | Pi County,Jiangsu | ||||

| Shangpi ( thượng bi ) | Pi County, Jiangsu | ||||

| Xuqu | Tu cú | Xuqu | Dongping County,Shandong | unknown | 620 BCE: to Lu |

| Yan | Yến | Bo ( bạc ), or Shengju ( thánh tụ ) | Fangshan District,Beijing | King Wu's reign | 222 BCE: to Qin |

| Ji( kế ) | Beijing | ||||

| Southern Yan | Nam yến | Yan | Yanjin County,Henan | unknown | unknown |

| Yan | Yên | Yan | Yanling County,Henan | King Wu's reign | 769 BCE: to Zheng |

| Yang | Dương | Yang | Yinan County,Shandong | unknown | 660 BCE: to Qi |

| Yin | Doãn | Yin | Xin'an County,Henan | King Xuan's reign | unknown |

| Ying | Ứng | Ying | Pingdingshan,Henan | King Cheng's reign | 646 BCE: to Chu |

| Yu | VuorVu | Yu | Qinyang, Henan | King Wu's reign | unknown |

| Yu | Vũ | Yu | Linyi,Shandong | unknown | 524 BCE: to Lu |

| Yuan | Nguyên | Yuan | Jiyuan,Henan | King Wu's reign | 635 BCE: to Jin |

| Yue | Việt | Kuaiji ( hội kê ) | Shaoxing,Zhejiang | unknown | 306 BCE: to Chu |

| Langya ( lang tà ) | Jiaonan,Shandong | ||||

| Wu ( ngô ) | Suzhou, Jiangsu | ||||

| Zeng,Sui | TằngorTùy | Sui | Suizhou,Hubei | unknown | unknown:to Chu |

| Zeng | Tằng | Zeng | Fangcheng County,Henan | before Western Zhou | 567 BCE: to Ju |

| Zhan | Chiêm | unknown | unknown | 827 BCE | unknown |

| Zhang | Chướng | Zhang | Dongping County, Shandong | early Western Zhou | 664 BCE: to Qi |

| Zheng | Trịnh | Zheng | Hua County, Shaanxi | 806 BCE | 375 BCE: to Han |

| Xinzheng ( tân trịnh ) | Xinzheng,Henan | ||||

| Zhongshan | Trung sơn | Gu ( cố ) | Dingzhou,Hebei | 506 BCE | 296 BCE: to Zhao |

| Lingshou ( linh thọ ) | Lingshou County,Hebei | ||||

| Zhou | Chu | Zhou | Fengxiang County,Shaanxi | King Wu's reign | unknown |

| Zhoulai | Châu lai | Zhoulai | Fengtai County, Anhui | 8th century BCE | 528 BCE: to Chu |

| Zhu | Chúc | Zhu | Changqing District,Jinan, Shandong | King Wu's reign | 768 BCE: to Qi |

| Zhu | Chú | Zhu | Feicheng,Shandong | King Wu's reign | unknown:to Qi |

| Zhuan | 鄟 | Zhuan | Tancheng, Shandong | unknown | 585 BCE: to Lu |

| Zhuanyu | Chuyên du | Zhuanyu | Pingyi County,Shandong | King Wu's reign | unknown |

| Zou,Zhu | TrâuorChu | Zhu ( chu ) | Qufu, Shandong | King Wu's reign | 4th century BCE: to Chu |

| Zou ( trâu ) | Zoucheng,Shandong | ||||

| Key: | |||||

| Hegemon | |||||

| Note: Capitals are listed in chronological order. | |||||

Notes[edit]

- ^There is no academic consensus on the end of the Spring and Autumn period. Criteria differ, but there is general agreement that thePartition of Jinmarks the watershed affair of state politically marking the subsequent Warring States period. Common choices include:

- 481 BCE. Final entry in theSpring and Autumn Annals.Usurpation of Qi by Tian:Tian Hengassassinated his duke along with the duke's advisors and most of his family, confiscating most of their lands.[2]

- 479 BCE. Death ofConfucius.[3]

- 475 or 476 BCE. Accession ofKing Yuan of Zhou.This is the year chosen bySima Qianin his deeply influentialRecords of the Grand Historian,motivated by the dearth of sources available for the following period givenQin Shi Huang's biblioclasm.The initial year of a new king was a methodological convenience. Modern Chinese sources generally prefer this choice.[4]

- 453 BCE. Partition of Jin: the clan of Zhi ( trí ), previously the most powerful aristocratic family in Jin, is eliminated at theBattle of Jinyang,leaving only the three clans who would become the successor states ofHan,Wei,andZhao.[5]

- 403 BCE. Partition of Jin: the successor states are formally recognized by the Zhou king. This year was the choice ofSima Guang,compiler of theZizhi Tongjian.[3]

- Some historians decline to assign a single year as the boundary.[6]Others will choose arbitrarily.[7]

- ^The Chinese language does not mark plurals. There is an increasing trend in languages with plural markers to translate the name of this period as "Springs and Autumns",[3]which better conveys the vicissitudes of time. The translation "Spring–Autumn period" also occurs in the literature.[8]

- ^The 148 states mentioned in theSpring and Autumn Annalsare not considered to comprise an exhaustive list.[15]

- ^Descent of the Wu ruling house from the Zhou ancestral line is not universally dismissed in modern scholarship.[40]

References[edit]

Citations[edit]

- ^Hsu 1999,p. 547.

- ^Lewis 1999,p. 598.

- ^abcFalkenhausen 1999,p. 450.

- ^General Office of the State Council 2021.

- ^Pines 2002.

- ^Cook 1995,p. 148.

- ^Kiser & Cai 2003,p. 512.

- ^Zhao Dingxin (2004). "Comment: Spurious Causation in a Historical Process: War and Bureaucratization in Early China".American Sociological Review.69(4). American Sociological Association: 603–607.doi:10.1177/000312240406900407.JSTOR3593067.S2CID143734027.

- ^Chen and Pines 2018,p. 4.

- ^Chin 2007,p. 43.

- ^Hsu 1999,p. 546

- ^abHigham 2004,p. 412

- ^abShaughnessy 1999,p. 350

- ^Lewis 2000,pp. 359, 363

- ^ab"5: Vương chế",Liji

- ^abcHsu 1999,p. 567

- ^Lewis 2000,p. 365.

- ^Hsu 1999,pp. 549–50.

- ^Hsu 1999,pp. 568, 570.

- ^Lewis 2000,p. 366.

- ^Hsu 1999,p. 567.

- ^Lewis 2000,p. 367.

- ^abcdeSima Qian;Sima Tan(1959) [90s BCE]. "4: Chu bổn kỷ".Records of the Grand HistorianSử ký.Zhonghua Shuju.

- ^Pines 2002,p. 3

- ^Hsu 1999,pp. 553–54.

- ^Hsu 1999,p. 555.

- ^Lewis 2000,pp. 366, 369.

- ^Hsu 1999,pp. 555–56.

- ^abHsu 1999,p. 560.

- ^Zuo Zhuan.(in Chinese) – viaWikisource.

- ^Hsu 1999,p. 559.

- ^Hsu 1999,pp. 560–61.

- ^"Duke Xuan",Zuozhuan

- ^Milburn 2016,p. 64.

- ^abPines 2002,p. 4.

- ^Sima Qian;Sima Tan(1959) [90s BCE]. "39: Tấn thế gia".Records of the Grand HistorianSử ký.Zhonghua Shuju.

- ^Rites of Zhou

- ^Milburn 2004,pp. 203–204.

- ^Milburn 2016,p. 104.

- ^Milburn 2004,p. 203.

- ^"Duke Cheng year 8".Zuo Zhuan.

- ^Hsu 1999,p. 561.

- ^abHsu 1999,p. 562.

- ^abPetersen 1992.

- ^abHui 2004,p. 186.

- ^E.g."17:10",Analects

- ^Sima Qian;Sima Tan(1959) [90s BCE]. "47: Khổng tử thế gia".Records of the Grand HistorianSử ký.Zhonghua Shuju.

- ^Li 2008a,pp. 120–123.

- ^Li 2008a,p. 114.

- ^Wei 2012,abstract.

- ^Li 2008a,pp. 123–124.

- ^Chen and Pines 2018,p. 5.

- ^Pines 2004,p. 23.

- ^Li 2008a,pp. 115–118.

- ^Ye, Fei, and Wang 2007,pp. 34–35

- ^Milburn 2016,p. 77.

- ^Tan 1996,pp. 22–30.

Sources[edit]

- Blakeley, Barry B (1977), "Functional disparities in the socio-political traditions of Spring and Autumn China: Part I: Lu and Ch'i",Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient,20(2): 208–243,doi:10.2307/3631778,JSTOR3631778

- Chen Minzhen ( trần dân trấn );Pines, Yuri(2018)."Where is King Ping? The History and Historiography of the Zhou Dynasty's Eastward Relocation".Asia Major.31(1). Academica Sinica: 1–27.JSTOR26571325.Retrieved2022-06-15.

- Chin, Annping(2007),The Authentic Confucius,Scribner,ISBN978-0-7432-4618-7

- Cook, Constance (1995)."Chinese Religions – 4000 BCE to 220 CE".The Journal of Asian Studies.54(1): 148.doi:10.1017/S0021911800021628.JSTOR2058953.S2CID162729516.

- General Office of the State Council of the People's Republic of China (2021)."Simple Table of Chinese History"Trung quốc lịch sử kỷ niên giản biểu(in Chinese).Retrieved9 April2023.

- Higham, Charles (2004),Encyclopedia of Ancient Asian Civilizations,Infobase

- Hui, Victoria Tin-bor (2004), "Toward a dynamic theory of international politics: Insights from comparing ancient China and early modern Europe",International Organization,58(1): 175–205,doi:10.1017/s0020818304581067,S2CID154664114

- Kiser, Edgar; Cai, Young (2003), "War and bureaucratization in Qin China: Exploring an anomalous case",American Sociological Review,68(4): 511–539,doi:10.2307/1519737,JSTOR1519737

- Lewis, Mark Edward(2000),"The City-State in Spring-and-Autumn China",in Hansen, Mogens Herman (ed.),A Comparative Study of Thirty City-State Cultures: An Investigation,vol. 21, Copenhagen: The Royal Danish Society of Arts and Letters, pp. 359–374,ISBN978-8778761774

- Li Feng(2008). "Transmitting Antiquity: The Origin and Paradigmization of the 'Five Ranks'".In Kuhn, Dieter; Stahl, Helga (eds.).Perceptions of Antiquity in Chinese Civilization.Würzberg: Würzburger Sinologische Schriften. pp. 103–134.

- Loewe, Michael;Shaughnessy, Edward L,eds. (1999),The Cambridge History of Ancient China: from the origins of civilization to 221 BC,Cambridge University Press,ISBN978-0521470308

- Hsu, Cho-yun."The Spring and Autumn Period".InCambridge History of Ancient China (1999),pp. 545–586.doi:10.1017/CHOL9780521470308.010

- Lewis, Mark Edward. "Warring States Political History". InCambridge History of Ancient China (1999),pp. 587–650.doi:10.1017/CHOL9780521470308.011

- Shaughnessy, Edward L. "Western Zhou History".InCambridge History of Ancient China (1999),pp. 292–351.doi:10.1017/CHOL9780521470308.007

- Falkenhausen, Lothar von. "The Waning of the Bronze Age". InCambridge History of Ancient China (1999),pp. 450–544.doi:10.1017/CHOL9780521470308.009

- Milburn, Olivia(2004). "Kingship and Inheritance in the State of Wu: Fraternal Succession in Spring and Autumn Period China (771–475 BC)".T'oung Pao.90(4/5). Leiden: Brill: 195–214.doi:10.1163/1568532043628359.JSTOR4528969.

- Milburn, Olivia (2016)."TheXinian:an ancient historical text from the Qinghua University collection of bamboo books ".Early China.39.Cambridge: Cambridge University Press: 53–109.doi:10.1017/eac.2016.2.JSTOR44075753.S2CID232154371.

- Petersen, Jens Østergård (1992). "What's in a Name? On the Sources concerning Sun Wu".Asia Major.3.5(1). Academica Sinica: 1–31.JSTOR41645475.

- Pines, Yuri (2002),Foundations of Confucian Thought: Intellectual Life in the Chunqiu Period (722–453 BCE),University of Hawai'i Press

- Pines, Yuri(2004). "The question of interpretation: Qin history in light of new epigraphic sources".Early China.29.Cambridge: Cambridge University Press: 1–44.doi:10.1017/S0362502800007082.JSTOR23354539.S2CID163441973.

- Tan Qixiang(1996).The Historical Atlas of China,Volume I.Beijing:China Cartographic Publishing House.pp. 22–30.ISBN978-7503118401.

- Wei Peng ngụy bồng (2012),The "five ranks of nobility" in the Western Zhou and Spring–Autumn periods: a studyTây chu xuân thu thời kỳ “Ngũ đẳng tước xưng” nghiên cứu,Nankai University: PhD dissertation

- Ye Lang; Fei Zhengang; Wang Tianyou (2007),China: five thousand years of history and civilization,Hong Kong: University of Hong Kong Press,ISBN978-9629371401

Further reading[edit]

- Ebrey, Patricia Buckley (1999).The Cambridge Illustrated History of China.Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.ISBN0-521-66991-X(paperback).

External links[edit]

- "Rulers of the states of Zhou",Dynasty,C text– linked to their occurrences in classical Chinese texts.

Media related toArt of the Spring and Autumn periodat Wikimedia Commons

Media related toArt of the Spring and Autumn periodat Wikimedia Commons