Steam turbine

| Steam turbine | |

|---|---|

The rotor of a modern steam turbine used in apower plant | |

| Classification | Heat engine |

| Industry | Energy |

| Application | Energy transformation |

| Inventor | Charles Algernon Parsons |

| Invented | 1884 |

Asteam turbineis amachinethat extractsthermal energyfrom pressurizedsteamand uses it to domechanical workon a rotating output shaft. Its modern manifestation was invented byCharles Parsonsin 1884.[1][2]Fabrication of a modern steam turbine involves advancedmetalworkto form high-gradesteel alloysinto precision parts using technologies that first became available in the 20th century; continued advances in durability and efficiency of steam turbines remains central to theenergy economicsof the 21st century.

The steam turbine is a form ofheat enginethat derives much of its improvement inthermodynamic efficiencyfrom the use of multiple stages in the expansion of the steam, which results in a closer approach to the ideal reversible expansion process.

Because theturbinegeneratesrotary motion,it can be coupled to ageneratorto harness its motion into electricity. Suchturbogeneratorsare the core ofthermal power stationswhich can be fueled byfossil fuels,nuclear fuels,geothermal,orsolar energy.About 42% of all electricity generation in the United States in the year 2022 was by use of steam turbines.[3]

Technical challenges includerotor imbalance,vibration,bearing wear,and uneven expansion (various forms ofthermal shock). In large installations, even the sturdiest turbine will shake itself apart if operated out of trim.

History

[edit]

The first device that may be classified as a reaction steam turbine was little more than a toy, the classicAeolipile,described in the 1st century byHero of AlexandriainRoman Egypt.[4][5]In 1551,Taqi al-DininOttoman Egyptdescribed a steam turbine with the practical application of rotating aspit.Steam turbines were also described by the ItalianGiovanni Branca(1629)[6]andJohn Wilkinsin England (1648).[7][8]The devices described by Taqi al-Din and Wilkins are today known assteam jacks.In 1672, animpulse turbinedriven small toy car was designed byFerdinand Verbiest.A more modern version of this car was produced some time in the late 18th century by an unknown German mechanic. In 1775 at SohoJames Wattdesigned a reaction turbine that was put to work there.[9]In 1807, Polikarp Zalesov designed and constructed an impulse turbine, using it for the fire pump operation.[10]In 1827 the Frenchmen Real and Pichon patented and constructed a compound impulse turbine.[11]

The modern steam turbine was invented in 1884 byCharles Parsons,whose first model was connected to adynamothat generated 7.5 kilowatts (10.1 hp) of electricity.[12]The invention of Parsons' steam turbine made cheap and plentiful electricity possible and revolutionized marine transport and naval warfare.[13]Parsons' design was areactiontype. His patent was licensed and the turbine scaled up shortly after by an American,George Westinghouse.The Parsons turbine also turned out to be easy to scale up. Parsons had the satisfaction of seeing his invention adopted for all major world power stations, and the size of generators had increased from his first 7.5 kilowatts (10.1 hp) set up to units of 50,000 kilowatts (67,000 hp) capacity. Within Parsons' lifetime, the generating capacity of a unit was scaled up by about 10,000 times,[14]and the total output from turbo-generators constructed by his firmC. A. Parsons and Companyand by their licensees, for land purposes alone, had exceeded thirty million horse-power.[12]

Other variations of turbines have been developed that work effectively with steam. Thede Laval turbine(invented byGustaf de Laval) accelerated the steam to full speed before running it against a turbine blade. De Laval'simpulse turbineis simpler and less expensive and does not need to be pressure-proof. It can operate with any pressure of steam, but is considerably less efficient.[citation needed]Auguste Rateaudeveloped a pressure compounded impulse turbine using the de Laval principle as early as 1896,[15]obtained a US patent in 1903, and applied the turbine to a French torpedo boat in 1904. He taught at theÉcole des mines de Saint-Étiennefor a decade until 1897, and later founded a successful company that was incorporated into theAlstomfirm after his death. One of the founders of the modern theory of steam and gas turbines wasAurel Stodola,a Slovak physicist and engineer and professor at the Swiss Polytechnical Institute (nowETH) in Zurich. His workDie Dampfturbinen und ihre Aussichten als Wärmekraftmaschinen(English: The Steam Turbine and its prospective use as a Heat Engine) was published in Berlin in 1903. A further bookDampf und Gas-Turbinen(English: Steam and Gas Turbines) was published in 1922.[16]

TheBrown-Curtis turbine,an impulse type, which had been originally developed and patented by the U.S. company International Curtis Marine Turbine Company, was developed in the 1900s in conjunction withJohn Brown & Company.It was used in John Brown-engined merchant ships and warships, including liners and Royal Navy warships.

Manufacturing

[edit]

The present day manufacturing industry for steam turbines consists of the following companies:

- WEG(Brazil)

- Harbin Electric,Shanghai Electric,Dongfang Electric(China)

- Doosan Škoda Power(Czech - South Korea)

- Alstom(France)

- Siemens,BTT-Bremer Turbinentechnik GmbH, K&K Turboservice GmbH (Germany)

- BHEL,Larsen & Toubro,Triveni Engineering & Industries(India)

- MAPNA(Iran)

- Ansaldo(Italy)

- Mitsubishi,KwHI,Toshiba,IHI(Japan)

- Silmash,Ural TW,Nevsky Turbine Plant (Nevsky NTW),KTZ,Energomash-Atomenergo,Power Machines,Leningradsky Metallichesky Zavod(Russia)

- Turboatom(Ukraine)

- EDF(France)

- Curtiss-Wright,Elliot Company,GE Vernova,Skinner Power Systems,Baker Hughes,Leonardo DRS,Chart Industries (United States)

- Trillium Flow Technologies (United Kingdom)

Types

[edit]Steam turbines are made in a variety of sizes ranging from small <0.75 kW (<1 hp) units (rare) used as mechanical drives for pumps, compressors and other shaft driven equipment, to 1,500 MW (2,000,000 hp) turbines used to generate electricity. There are several classifications for modern steam turbines.

Blade and stage design

[edit]

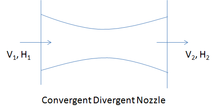

Turbine blades are of two basic types, blades andnozzles.Blades move entirely due to the impact of steam on them and their profiles do not converge. This results in a steam velocity drop and essentially no pressure drop as steam moves through the blades. A turbine composed of blades alternating with fixed nozzles is called animpulse turbine,Curtis turbine,Rateau turbine,orBrown-Curtis turbine.Nozzles appear similar to blades, but their profiles converge near the exit. This results in a steam pressure drop and velocity increase as steam moves through the nozzles. Nozzles move due to both the impact of steam on them and the reaction due to the high-velocity steam at the exit. A turbine composed of moving nozzles alternating with fixed nozzles is called areaction turbineorParsons turbine.

Except for low-power applications, turbine blades are arranged in multiple stages in series, calledcompounding,which greatly improvesefficiencyat low speeds.[18]A reaction stage is a row of fixed nozzles followed by a row of moving nozzles. Multiple reaction stages divide the pressure drop between the steam inlet and exhaust into numerous small drops, resulting in apressure-compoundedturbine. Impulse stages may be either pressure-compounded, velocity-compounded, or pressure-velocity compounded. A pressure-compounded impulse stage is a row of fixed nozzles followed by a row of moving blades, with multiple stages for compounding. This is also known as a Rateau turbine, after its inventor. Avelocity-compoundedimpulse stage (invented by Curtis and also called a "Curtis wheel" ) is a row of fixed nozzles followed by two or more rows of moving blades alternating with rows of fixed blades. This divides the velocity drop across the stage into several smaller drops.[19]A series of velocity-compounded impulse stages is called apressure-velocity compoundedturbine.

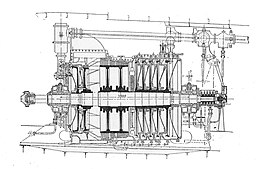

By 1905, when steam turbines were coming into use on fast ships (such asHMSDreadnought) and in land-based power applications, it had been determined that it was desirable to use one or more Curtis wheels at the beginning of a multi-stage turbine (where the steam pressure is highest), followed by reaction stages. This was more efficient with high-pressure steam due to reduced leakage between the turbine rotor and the casing.[20]This is illustrated in the drawing of the German 1905AEGmarine steam turbine. The steam from theboilersenters from the right at high pressure through athrottle,controlled manually by an operator (in this case asailorknown as the throttleman). It passes through five Curtis wheels and numerous reaction stages (the small blades at the edges of the two large rotors in the middle) before exiting at low pressure, almost certainly to acondenser.The condenser provides a vacuum that maximizes the energy extracted from the steam, and condenses the steam intofeedwaterto be returned to the boilers. On the left are several additional reaction stages (on two large rotors) that rotate the turbine in reverse for astern operation, with steam admitted by a separate throttle. Since ships are rarely operated in reverse, efficiency is not a priority in astern turbines, so only a few stages are used to save cost.

Blade design challenges

[edit]A major challenge facing turbine design was reducing thecreepexperienced by the blades. Because of the high temperatures and high stresses of operation, steam turbine materials become damaged through these mechanisms. As temperatures are increased in an effort to improve turbine efficiency, creep becomes significant. To limit creep, thermal coatings andsuperalloyswith solid-solution strengthening andgrain boundary strengtheningare used in blade designs.

Protective coatings are used to reduce the thermal damage and to limitoxidation.These coatings are often stabilizedzirconium dioxide-based ceramics. Using a thermal protective coating limits the temperature exposure of the nickel superalloy. This reduces the creep mechanisms experienced in the blade. Oxidation coatings limit efficiency losses caused by a buildup on the outside of the blades, which is especially important in the high-temperature environment.[21]

The nickel-based blades are alloyed with aluminum and titanium to improve strength and creep resistance. Themicrostructureof these alloys is composed of different regions of composition. A uniform dispersion of the gamma-prime phase – a combination of nickel, aluminum, and titanium – promotes the strength and creep resistance of the blade due to the microstructure.[22]

Refractoryelements such asrheniumandrutheniumcan be added to the alloy to improve creep strength. The addition of these elements reduces the diffusion of the gamma prime phase, thus preserving thefatigueresistance, strength, and creep resistance.[23]

Steam supply and exhaust conditions

[edit]

Turbine types include condensing, non-condensing, reheat, extracting and induction.

Condensing turbines

[edit]Condensing turbines are most commonly found in electrical power plants. These turbines receive steam from aboilerand exhaust it to acondenser.The exhausted steam is at a pressure well below atmospheric, and is in a partially condensed state, typically of aqualitynear 90%.

Non-condensing turbines

[edit]Non-condensing turbines are most widely used for process steam applications, in which the steam will be used for additional purposes after being exhausted from the turbine. The exhaust pressure is controlled by a regulating valve to suit the needs of the process steam pressure. These are commonly found at refineries, district heating units, pulp and paper plants, anddesalinationfacilities where large amounts of low pressure process steam are needed.

Reheat turbines

[edit]Reheat turbines are also used almost exclusively in electrical power plants. In a reheat turbine, steam flow exits from a high-pressure section of the turbine and is returned to the boiler where additional superheat is added. The steam then goes back into an intermediate pressure section of the turbine and continues its expansion. Using reheat in a cycle increases the work output from the turbine and also the expansion reaches conclusion before the steam condenses, thereby minimizing the erosion of the blades in last rows. In most of the cases, maximum number of reheats employed in a cycle is 2 as the cost of super-heating the steam negates the increase in the work output from turbine.

Extracting turbines

[edit]Extracting type turbines are common in all applications. In an extracting type turbine, steam is released from various stages of the turbine, and used for industrial process needs or sent to boilerfeedwater heatersto improve overall cycle efficiency. Extraction flows may be controlled with a valve, or left uncontrolled. Extracted steam results in aloss of powerin the downstream stages of the turbine.

Induction turbines introduce low pressure steam at an intermediate stage to produce additional power.

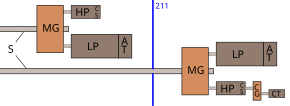

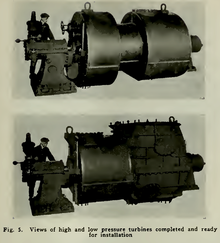

Casing or shaft arrangements

[edit]These arrangements include single casing, tandem compound and cross compound turbines. Single casing units are the most basic style where a single casing and shaft are coupled to a generator. Tandem compound are used where two or more casings are directly coupled together to drive a single generator. A cross compound turbine arrangement features two or more shafts not in line driving two or more generators that often operate at different speeds. A cross compound turbine is typically used for many large applications. A typical 1930s-1960s naval installation is illustrated below; this shows high- and low-pressure turbines driving a common reduction gear, with a geared cruising turbine on one high-pressure turbine.

Two-flow rotors

[edit]

The moving steam imparts both a tangential and axial thrust on the turbine shaft, but the axial thrust in a simple turbine is unopposed. To maintain the correct rotor position and balancing, this force must be counteracted by an opposing force.Thrust bearingscan be used for the shaft bearings, the rotor can use dummy pistons, it can bedouble flow- the steam enters in the middle of the shaft and exits at both ends, or a combination of any of these. In adouble flowrotor, the blades in each half face opposite ways, so that the axial forces negate each other but the tangential forces act together. This design of rotor is also calledtwo-flow,double-axial-flow,ordouble-exhaust.This arrangement is common in low-pressure casings of a compound turbine.[24]

Principle of operation and design

[edit]An ideal steam turbine is considered to be anisentropic process,or constant entropy process, in which the entropy of the steam entering the turbine is equal to the entropy of the steam leaving the turbine. No steam turbine is truly isentropic, however, with typical isentropic efficiencies ranging from 20 to 90% based on the application of the turbine. The interior of a turbine comprises several sets of blades orbuckets.One set of stationary blades is connected to the casing and one set of rotating blades is connected to the shaft. The sets intermesh with certain minimum clearances, with the size and configuration of sets varying to efficiently exploit the expansion of steam at each stage.

Impulse turbines

[edit]

An impulse turbine has fixed nozzles that orient the steam flow into high speed jets. These jets contain significant kinetic energy, which is converted into shaft rotation by the bucket-like shaped rotor blades, as the steam jet changes direction. A pressure drop occurs across only the stationary blades, with a net increase in steam velocity across the stage. As the steam flows through the nozzle its pressure falls from inlet pressure to the exit pressure (atmospheric pressure or, more usually, the condenser vacuum). Due to this high ratio of expansion of steam, the steam leaves the nozzle with a very high velocity. The steam leaving the moving blades has a large portion of the maximum velocity of the steam when leaving the nozzle. The loss of energy due to this higher exit velocity is commonly called the carry over velocity or leaving loss.

The law ofmoment of momentumstates that the sum of the moments of external forces acting on a fluid which is temporarily occupying thecontrol volumeis equal to the net time change of angular momentum flux through the control volume.

The swirling fluid enters the control volume at radiuswith tangential velocityand leaves at radiuswith tangential velocity.

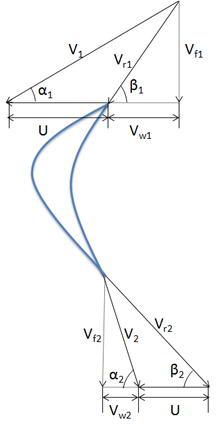

Avelocity trianglepaves the way for a better understanding of the relationship between the various velocities. In the adjacent figure we have:

- andare the absolute velocities at the inlet and outlet respectively.

- andare the flow velocities at the inlet and outlet respectively.

- andare the swirl velocities at the inlet and outlet respectively, in the moving reference.

- andare the relative velocities at the inlet and outlet respectively.

- is the velocity of the blade.

- is the guide vane angle andis the blade angle.

Then by the law of moment of momentum, the torque on the fluid is given by:

For an impulse steam turbine:.Therefore, the tangential force on the blades is.The work done per unit time or power developed:.

When ω is the angular velocity of the turbine, then the blade speed is.The power developed is then.

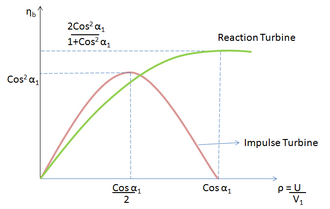

Blade efficiency

[edit]Blade efficiency () can be defined as the ratio of the work done on the blades to kinetic energy supplied to the fluid, and is given by

Stage efficiency

[edit]

A stage of an impulse turbine consists of a nozzle set and a moving wheel. The stage efficiency defines a relationship between enthalpy drop in the nozzle and work done in the stage. Whereis the specific enthalpy drop of steam in the nozzle.

By thefirst law of thermodynamics: Assuming thatis appreciably less than,we get.Furthermore, stage efficiency is theproductof blade efficiency and nozzle efficiency, or.

Nozzle efficiency is given by,where the enthalpy (in J/Kg) of steam at the entrance of the nozzle isand the enthalpy of steam at the exit of the nozzle is. The ratio of the cosines of the blade angles at the outlet and inlet can be taken and denoted.The ratio of steam velocities relative to the rotor speed at the outlet to the inlet of the blade is defined by the friction coefficient.

and depicts the loss in the relative velocity due to friction as the steam flows around the blades (for smooth blades).

The ratio of the blade speed to the absolute steam velocity at the inlet is termed the blade speed ratio.

is maximum whenor,.That impliesand therefore.Now(for a single stage impulse turbine).

Therefore, the maximum value of stage efficiency is obtained by putting the value ofin the expression of.

We get:.

For equiangular blades,,therefore,and we get.If the friction due to the blade surface is neglected then.

Conclusions on maximum efficiency

[edit]- For a given steam velocity work done per kg of steam would be maximum whenor.

- Asincreases, the work done on the blades reduces, but at the same time surface area of the blade reduces, therefore there are less frictional losses.

Reaction turbines

[edit]In thereaction turbine,therotorblades themselves are arranged to form convergentnozzles.This type of turbine makes use of the reaction force produced as the steam accelerates through the nozzles formed by the stator. Steam is directed onto the rotor by the fixed vanes of thestator.It leaves the stator as a jet that fills the entire circumference of the rotor. The steam then changes direction and increases its speed relative to the speed of the blades. A pressure drop occurs across both the stator and the rotor, with steam accelerating through the stator and decelerating through the rotor, with no net change in steam velocity across the stage but with a decrease in both pressure and temperature, reflecting the work performed in the driving of the rotor.

Blade efficiency

[edit]Energy input to the blades in a stage:

is equal to the kinetic energy supplied to the fixed blades (f) + the kinetic energy supplied to the moving blades (m).

Or,= enthalpy drop over the fixed blades,+ enthalpy drop over the moving blades,.

The effect of expansion of steam over the moving blades is to increase the relative velocity at the exit. Therefore, the relative velocity at the exitis always greater than the relative velocity at the inlet.

In terms of velocities, the enthalpy drop over the moving blades is given by: (it contributes to a change in static pressure)

The enthalpy drop in the fixed blades, with the assumption that the velocity of steam entering the fixed blades is equal to the velocity of steam leaving the previously moving blades is given by: where V0is the inlet velocity of steam in the nozzle

is very small and hence can be neglected. Therefore,

A very widely used design has halfdegree of reactionor 50% reaction and this is known asParson's turbine.This consists of symmetrical rotor and stator blades. For this turbine the velocity triangle is similar and we have: , ,

AssumingParson's turbineand obtaining all the expressions we get From the inlet velocity triangle we have Work done (for unit mass flow per second):

Therefore, theblade efficiencyis given by

Condition of maximum blade efficiency

[edit]

If,then

For maximum efficiency,we get

and this finally gives

Therefore,is found by putting the value ofin the expression of blade efficiency

Operation and maintenance

[edit]

Because of the high pressures used in the steam circuits and the materials used, steam turbines and their casings have highthermal inertia.When warming up a steam turbine for use, the main steam stop valves (after the boiler) have a bypass line to allow superheated steam to slowly bypass the valve and proceed to heat up the lines in the system along with the steam turbine. Also, aturning gearis engaged when there is no steam to slowly rotate the turbine to ensure even heating to preventuneven expansion.After first rotating the turbine by the turning gear, allowing time for the rotor to assume a straight plane (no bowing), then the turning gear is disengaged and steam is admitted to the turbine, first to the astern blades then to the ahead blades slowly rotating the turbine at 10–15 RPM (0.17–0.25 Hz) to slowly warm the turbine. The warm-up procedure for large steam turbines may exceed ten hours.[25]

During normal operation, rotor imbalance can lead to vibration, which, because of the high rotation velocities, could lead to a blade breaking away from the rotor and through the casing. To reduce this risk, considerable efforts are spent to balance the turbine. Also, turbines are run with high-quality steam: eithersuperheated (dry) steam,orsaturatedsteam with a high dryness fraction. This prevents the rapid impingement and erosion of the blades which occurs when condensed water is blasted onto the blades (moisture carry over). Also, liquid water entering the blades may damage the thrust bearings for the turbine shaft. To prevent this, along with controls and baffles in the boilers to ensure high-quality steam, condensate drains are installed in the steam piping leading to the turbine.

Maintenance requirements of modern steam turbines are simple and incur low costs (typically around $0.005 per kWh);[25]their operational life often exceeds 50 years.[25]

Speed regulation

[edit]

The control of a turbine with agovernoris essential, as turbines need to be run up slowly to prevent damage and some applications (such as the generation of alternating current electricity) require precise speed control.[26]Uncontrolled acceleration of the turbine rotor can lead to an overspeed trip, which causes the governor and throttle valves that control the flow of steam to the turbine to close. If these valves fail then the turbine may continue accelerating until it breaks apart, often catastrophically. Turbines are expensive to make, requiring precision manufacture and special quality materials.

During normal operation in synchronization with the electricity network, power plants are governed with a five percentdroop speed control.This means the full load speed is 100% and the no-load speed is 105%. This is required for the stable operation of the network without hunting and drop-outs of power plants. Normally the changes in speed are minor. Adjustments in power output are made by slowly raising the droop curve by increasing the spring pressure on acentrifugal governor.Generally this is a basic system requirement for all power plants because the older and newer plants have to be compatible in response to the instantaneous changes in frequency without depending on outside communication.[27]

Thermodynamics of steam turbines

[edit]

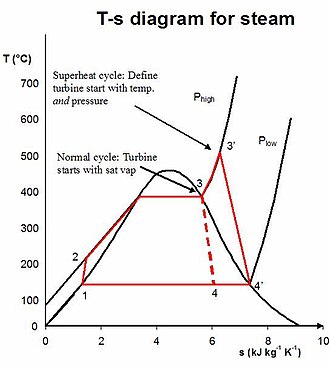

The steam turbine operates on basic principles ofthermodynamicsusing the part 3-4 of theRankine cycleshown in the adjoining diagram.Superheatedsteam (or dry saturated steam, depending on application) leaves the boiler at high temperature and high pressure. At entry to the turbine, the steam gains kinetic energy by passing through a nozzle (a fixed nozzle in an impulse type turbine or the fixed blades in a reaction type turbine). When the steam leaves the nozzle it is moving at high velocity towards the blades of the turbine rotor. A force is created on the blades due to the pressure of the vapor on the blades causing them to move. A generator or other such device can be placed on the shaft, and the energy that was in the steam can now be stored and used. The steam leaves the turbine as asaturated vapor(or liquid-vapor mix depending on application) at a lower temperature and pressure than it entered with and is sent to the condenser to be cooled.[28]The first law enables us to find a formula for the rate at which work is developed per unit mass. Assuming there is no heat transfer to the surrounding environment and that the changes in kinetic and potential energy are negligible compared to the change in specificenthalpywe arrive at the following equation

where

- Ẇis the rate at which work is developed per unit time

- ṁis the rate of mass flow through the turbine

Isentropic efficiency

[edit]To measure how well a turbine is performing we can look at itsisentropicefficiency. This compares the actual performance of the turbine with the performance that would be achieved by an ideal, isentropic, turbine.[29]When calculating this efficiency, heat lost to the surroundings is assumed to be zero. Steam's starting pressure and temperature is the same for both the actual and the ideal turbines, but at turbine exit, steam's energy content ('specific enthalpy') for the actual turbine is greater than that for the ideal turbine because of irreversibility in the actual turbine. The specific enthalpy is evaluated at the same steam pressure for the actual and ideal turbines in order to give a good comparison between the two.

The isentropic efficiency is found by dividing the actual work by the ideal work.[29]

where

- h3is the specific enthalpy at state three

- h4is the specific enthalpy at state 4 for the actual turbine

- h4sis the specific enthalpy at state 4s for the isentropic turbine

(but note that the adjacent diagram does not show state 4s: it is vertically below state 3)

Direct drive

[edit]

Electrical power stationsuse large steam turbines drivingelectric generatorsto produce most (about 80%) of the world's electricity. The advent of large steam turbines made central-station electricity generation practical, since reciprocating steam engines of large rating became very bulky, and operated at slow speeds. Most central stations arefossil fuel power plantsandnuclear power plants;some installations usegeothermalsteam, or useconcentrated solar power(CSP) to create the steam. Steam turbines can also be used directly to drive largecentrifugal pumps,such asfeedwater pumpsat athermal power plant.

The turbines used for electric power generation are most often directly coupled to their generators. As the generators must rotate at constant synchronous speeds according to the frequency of the electric power system, the most common speeds are 3,000 RPM for 50 Hz systems, and 3,600 RPM for 60 Hz systems. Since nuclear reactors have lower temperature limits than fossil-fired plants, with lower steamquality,the turbine generator sets may be arranged to operate at half these speeds, but with four-pole generators, to reduce erosion of turbine blades.[30]

Marine propulsion

[edit]

Insteamships,advantages of steam turbines over reciprocating engines are smaller size, lower maintenance, lighter weight, and lower vibration. A steam turbine is efficient only when operating in the thousands of RPM, while the most effective propeller designs are for speeds less than 300 RPM; consequently, precise (thus expensive) reduction gears are usually required, although numerous early ships throughWorld War I,such asTurbinia,had direct drive from the steam turbines to the propeller shafts. Another alternative isturbo-electric transmission,in which an electrical generator run by the high-speed turbine is used to run one or more slow-speed electric motors connected to the propeller shafts; precision gear cutting may be a production bottleneck during wartime. Turbo-electric drive was most used in large US warships designed during World War I and in some fast liners, and was used in some troop transports and mass-productiondestroyer escortsinWorld War II.

The higher cost of turbines and the associated gears or generator/motor sets is offset by lower maintenance requirements and the smaller size of a turbine in comparison with a reciprocating engine of equal power, although the fuel costs are higher than those of a diesel engine because steam turbines have lowerthermal efficiency.To reduce fuel costs the thermal efficiency of both types of engine have been improved over the years.

Early development

[edit]The development of steam turbine marine propulsion from 1894 to 1935 was dominated by the need to reconcile the high efficient speed of the turbine with the low efficient speed (less than 300 rpm) of the ship's propeller at an overall cost competitive withreciprocating engines.In 1894, efficient reductiongearswere not available for the high powers required by ships, sodirect drivewas necessary. InTurbinia,which has direct drive to each propeller shaft, the efficient speed of the turbine was reduced after initial trials by directing the steam flow through all three direct drive turbines (one on each shaft) in series, probably totaling around 200 turbine stages operating in series. Also, there were three propellers on each shaft for operation at high speeds.[31]The high shaft speeds of the era are represented by one of the first US turbine-powereddestroyers,USSSmith,launched in 1909, which had direct drive turbines and whose three shafts turned at 724 rpm at 28.35 knots (52.50 km/h; 32.62 mph).[32]

The use of turbines in several casings exhausting steam to each other in series became standard in most subsequent marine propulsion applications, and is a form ofcross-compounding.The first turbine was called the high pressure (HP) turbine, the last turbine was the low pressure (LP) turbine, and any turbine in between was an intermediate pressure (IP) turbine. A much later arrangement thanTurbiniacan be seen onRMSQueen MaryinLong Beach, California,launched in 1934, in which each shaft is powered by four turbines in series connected to the ends of the two input shafts of a single-reduction gearbox. They are the HP, 1st IP, 2nd IP, and LP turbines.

Cruising machinery and gearing

[edit]The quest for economy was even more important when cruising speeds were considered. Cruising speed is roughly 50% of a warship's maximum speed and 20-25% of its maximum power level. This would be a speed used on long voyages when fuel economy is desired. Although this brought the propeller speeds down to an efficient range, turbine efficiency was greatly reduced, and early turbine ships had poor cruising ranges. A solution that proved useful through most of the steam turbine propulsion era was the cruising turbine. This was an extra turbine to add even more stages, at first attached directly to one or more shafts, exhausting to a stage partway along the HP turbine, and not used at high speeds. As reduction gears became available around 1911, some ships, notably thebattleshipUSSNevada,had them on cruising turbines while retaining direct drive main turbines. Reduction gears allowed turbines to operate in their efficient range at a much higher speed than the shaft, but were expensive to manufacture.

Cruising turbines competed at first with reciprocating engines for fuel economy. An example of the retention of reciprocating engines on fast ships was the famousRMSOlympicof 1911, which along with her sistersRMSTitanicandHMHSBritannichad triple-expansion engines on the two outboard shafts, both exhausting to an LP turbine on the center shaft. After adopting turbines with theDelaware-class battleshipslaunched in 1909, theUnited States Navyreverted to reciprocating machinery on theNew York-class battleshipsof 1912, then went back to turbines onNevadain 1914. The lingering fondness for reciprocating machinery was because the US Navy had no plans for capital ships exceeding 21 knots (39 km/h; 24 mph) until after World War I, so top speed was less important than economical cruising. The United States had acquired thePhilippinesandHawaiias territories in 1898, and lacked the BritishRoyal Navy's worldwide network ofcoaling stations.Thus, the US Navy in 1900–1940 had the greatest need of any nation for fuel economy, especially as the prospect of war withJapanarose following World War I. This need was compounded by the US not launching any cruisers 1908–1920, so destroyers were required to perform long-range missions usually assigned to cruisers. So, various cruising solutions were fitted on US destroyers launched 1908–1916. These included small reciprocating engines and geared or ungeared cruising turbines on one or two shafts. However, once fully geared turbines proved economical in initial cost and fuel they were rapidly adopted, with cruising turbines also included on most ships. Beginning in 1915 all new Royal Navy destroyers had fully geared turbines, and the United States followed in 1917.

In theRoyal Navy,speed was a priority until theBattle of Jutlandin mid-1916 showed that in thebattlecruiserstoo much armour had been sacrificed in its pursuit. The British used exclusively turbine-powered warships from 1906. Because they recognized that a long cruising range would be desirable given their worldwide empire, some warships, notably theQueen Elizabeth-class battleships,were fitted with cruising turbines from 1912 onwards following earlier experimental installations.

In the US Navy, theMahan-class destroyers,launched 1935–36, introduced double-reduction gearing. This further increased the turbine speed above the shaft speed, allowing smaller turbines than single-reduction gearing. Steam pressures and temperatures were also increasing progressively, from 300 psi (2,100 kPa)/425 °F (218 °C) [saturated steam] on the World War I-eraWickesclassto 615 psi (4,240 kPa)/850 °F (454 °C) [superheated steam] on some World War IIFletcher-class destroyersand later ships.[33][34]A standard configuration emerged of an axial-flow high-pressure turbine (sometimes with a cruising turbine attached) and a double-axial-flow low-pressure turbine connected to a double-reduction gearbox. This arrangement continued throughout the steam era in the US Navy and was also used in some Royal Navy designs.[35][36]Machinery of this configuration can be seen on many preserved World War II-era warships in several countries.[37]

When US Navy warship construction resumed in the early 1950s, most surface combatants and aircraft carriers used 1,200 psi (8,300 kPa)/950 °F (510 °C) steam.[38]This continued until the end of the US Navy steam-powered warship era with theKnox-classfrigatesof the early 1970s. Amphibious and auxiliary ships continued to use 600 psi (4,100 kPa) steam post-World War II, withUSSIwo Jima,launched in 2001, possibly the last non-nuclear steam-powered ship built for the US Navy.

Turbo-electric drive

[edit]

Turbo-electric drivewas introduced on the battleshipUSSNew Mexico,launched in 1917. Over the next eight years the US Navy launched five additional turbo-electric-powered battleships and two aircraft carriers (initially ordered asLexington-class battlecruisers). Ten more turbo-electric capital ships were planned, but cancelled due to the limits imposed by theWashington Naval Treaty.

AlthoughNew Mexicowas refitted with geared turbines in a 1931–1933 refit, the remaining turbo-electric ships retained the system throughout their careers. This system used two large steam turbine generators to drive an electric motor on each of four shafts. The system was less costly initially than reduction gears and made the ships more maneuverable in port, with the shafts able to reverse rapidly and deliver more reverse power than with most geared systems.

Some ocean liners were also built with turbo-electric drive, as were some troop transports and mass-productiondestroyer escortsinWorld War II.However, when the US designed the "treaty cruisers", beginning withUSSPensacolalaunched in 1927, geared turbines were used to conserve weight, and remained in use for all fast steam-powered ships thereafter.

Current usage

[edit]Since the 1980s, steam turbines have been replaced bygas turbineson fast ships and bydiesel engineson other ships; exceptions arenuclear-powered ships and submarinesandLNG carriers.[39]Someauxiliary shipscontinue to use steam propulsion.

In the U.S. Navy, the conventionally powered steam turbine is still in use on all but one of theWasp-classamphibious assault ships. TheRoyal Navydecommissioned its last conventional steam-powered surface warship class, theFearless-classlanding platform dock,in 2002, with theItalian Navyfollowing in 2006 by decommissioning its last conventional steam-powered surface warships, theAudace-classdestroyers.In 2013, theFrench Navyended its steam era with the decommissioning of its lastTourville-classfrigate.Amongst the otherblue-water navies,the Russian Navy currently operates steam-poweredKuznetsov-classaircraft carriersandSovremenny-classdestroyers.TheIndian Navycurrently operates INSVikramaditya,a modifiedKiev-classaircraft carrier;it also operates threeBrahmaputra-classfrigatescommissioned in the early 2000s. The Chinese Navy currently operates steam-poweredKuznetsov-classaircraft carriers,Sovremenny-classdestroyersalong withLuda-classdestroyersand the loneType 051B destroyer.Most other naval forces have either retired or re-engined their steam-powered warships. As of 2020, theMexican Navyoperates four steam-powered former U.S.Knox-classfrigates.TheEgyptian Navyand theRepublic of China Navyrespectively operate two and six former U.S.Knox-classfrigates.TheEcuadorian Navycurrently operates two steam-poweredCondell-classfrigates(modifiedLeander-classfrigates).

Today, propulsion steam turbine cycle efficiencies have yet to break 50%, yet diesel engines routinely exceed 50%, especially in marine applications.[40][41][42]Diesel power plants also have lower operating costs since fewer operators are required. Thus, conventional steam power is used in very few new ships. An exception isLNG carrierswhich often find it more economical to useboil-off gaswith a steam turbine than to re-liquify it.

Nuclear-powered ships and submarinesuse a nuclear reactor to create steam for turbines. As of 2024, the main propulsion steam turbines (HP & LP) forUnited States Navynuclear-poweredNimitzandFordclassaircraft carriersare manufactured by theCurtiss-Wright Corporationin Summerville, SC.

Nuclear power is often chosen where diesel power would be impractical (as insubmarineapplications) or the logistics of refuelling pose significant problems (for example,icebreakers). It has been estimated that the reactor fuel for theRoyal Navy'sVanguard-class submarinesis sufficient to last 40 circumnavigations of the globe – potentially sufficient for the vessel's entire service life. Nuclear propulsion has only been applied to a very fewcommercial vesselsdue to the expense of maintenance and the regulatory controls required on nuclear systems and fuel cycles.

Locomotives

[edit]A steam turbine locomotive engine is asteam locomotivedriven by a steam turbine. The first steam turbine rail locomotive was built in 1908 for the Officine Meccaniche Miani Silvestri Grodona Comi, Milan, Italy. In 1924Kruppbuilt the steam turbine locomotive T18 001, operational in 1929, forDeutsche Reichsbahn.

The main advantages of a steam turbine locomotive are better rotational balance and reducedhammer blowon the track. However, a disadvantage is less flexible output power so that turbine locomotives were best suited for long-haul operations at a constant output power.[43]

Testing

[edit]British, German, other national and international test codes are used to standardize the procedures and definitions used to test steam turbines. Selection of the test code to be used is an agreement between the purchaser and the manufacturer, and has some significance to the design of the turbine and associated systems.

In the United States,ASMEhas produced several performance test codes on steam turbines. These include ASME PTC 6–2004, Steam Turbines, ASME PTC 6.2-2011, Steam Turbines inCombined Cycles,PTC 6S-1988, Procedures for Routine Performance Test of Steam Turbines. These ASME performance test codes have gained international recognition and acceptance for testing steam turbines. The single most important and differentiating characteristic of ASME performance test codes, including PTC 6, is that the test uncertainty of the measurement indicates the quality of the test and is not to be used as a commercial tolerance.[44]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^Stodola 1927.

- ^"Sir Charles Algernon Parsons".Encyclopædia Britannica.n.d.Retrieved19 September2010.

- ^"Electricity Net Generation From An Electric Turbine".US EIA.March 2024.

- ^Keyser 1992,pp. 107–124.

- ^O'Connor & Robertson 1999.

- ^Nag 2002,pp. 432–.

- ^"Taqi al-Din and the First Steam Turbine, 1551 A.D."History of Science and Technology in Islam.Archived fromthe originalon 18 February 2008.

- ^Hassan 1976,p. 34–35.

- ^"James Watt".steamindex.com.

- ^Савельев Н., Сибирские механики П. М. Залесов и М. С. Лаунин, Новосибирск. 1953

- ^Stodola & Loewenstein 1945.

- ^ab"The Steam Turbine".Birr Castle.Archived fromthe originalon 13 May 2010.Retrieved10 May2009.

- ^"Charles Parsons 1854 – 1931".Archived fromthe originalon 5 May 2010.Retrieved10 May2009.

- ^Parsons 1911.

- ^Giampaolo 2014,p. 9.

- ^Stodola 2013.

- ^"SocGen - China Losing Its Shine".documents.mx.Archived fromthe originalon 23 December 2015.Retrieved3 November2015.

- ^Parsons 1911,pp. 7–8.

- ^Parsons 1911,pp. 20–22.

- ^Parsons 1911,pp. 23–25.

- ^Tamarin 2002,p. 5–.

- ^Bhadeshia 2003.

- ^Latief & Kakehi 2013.

- ^"Steam Turbines (Course No. M-3006)"(PDF).PhD Engineer.Archived(PDF)from the original on 2 April 2012.Retrieved22 September2011.

- ^abc"Technology Characterization: Steam Turbines"(PDF).U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. December 2008. p. 13. Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 18 November 2012.Retrieved25 February2013.

- ^Whitaker 2006,p. 35.

- ^"Speed Droop and Power Generation. Application Note 01302"(pdf). Woodward. 1991.[permanent dead link]

- ^"Thermodynamics Steam Turbine".www.roymech.co.uk.Archivedfrom the original on 8 January 2011.

- ^abMoran et al. 2010.

- ^Leyzerovich 2005,p. 111.

- ^Parsons 1911,pp. 26–31.

- ^Friedman 2004,p. 23–24.

- ^"1,500-ton destroyers in World War II".destroyerhistory.org.Archivedfrom the original on 5 November 2013.

- ^Friedman 2004,p. 472.

- ^Bowie 2010.

- ^"Steam Turbines".www.leander-project.homecall.co.uk.Archivedfrom the original on 22 November 2013.

- ^"Historic Naval Ships Association".Archived fromthe originalon 22 June 2013.

- ^Friedman 2004,p. 477.

- ^"Mitsubishi Heavy starts construction of first Sayaendo series LNG carrier".December 2012.Archivedfrom the original on 7 August 2014.

- ^Deckers 2003,p. 14–15.

- ^Leyzerovich 2002.

- ^Takaishi, Tatsuo; Numata, Akira; Nakano, Ryouji; Sakaguchi, Katsuhiko (March 2008)."Approach to High Efficiency Diesel and Gas Engines"(PDF).Technical Review.Mitsubishi Heavy Industries.Retrieved6 May2019.

- ^Streeter 2007,p. 85.

- ^Sanders 2004,p. 292.

Sources

[edit]- Bayar, Tildy (31 July 2014)."Global gas and steam turbine market to reach $43.5bn by 2020".Power Engineering International. Archived fromthe originalon 30 August 2016.Retrieved3 November2015.

- Bhadeshia, HKDH (2003)."Nickel Based Superalloys".University of Cambridge.Retrieved4 September2008.

- Bowie, David (2010)."Cruising Turbines of the Y-100 Naval Propulsion Machinery"(PDF).

- Deckers, Matthias (Summer 2003)."CFX Aids Design of World's Most Efficient Steam Turbine"(PDF).CFXUpdate(23). Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 24 October 2005.

- Giampaolo, Tony (2014).Gas Turbine Handbook Principles and Practices By Tony Giampaolo: Gas Turbine Handbook.Digital Designs.[permanent dead link]

- Friedman, Norman (2004).U.S. Destroyers: An Illustrated Design History.Annapolis: Naval Institute Press.ISBN978-1-55750-442-5.

- Hassan, Ahmad Y(1976).Taqi al-Din and Arabic Mechanical Engineering.Institute for the History of Arabic Science,University of Aleppo.

- Keyser, Paul (1992). "A new look at Heron's Steam Engine".Archive for History of Exact Sciences.44(2): 107–124.doi:10.1007/BF00374742.ISSN0003-9519.S2CID122957344.

- Latief, Fahamsyah H; Kakehi, Koji (2013). "Effects of Re content and crystallographic orientation on creep behavior of aluminized Ni-base single crystal superalloys".Materials & Design.49:485–492.doi:10.1016/j.matdes.2013.01.022.ISSN0261-3069.

- Leyzerovich, Alexander S (1 August 2002)."New Benchmarks for Steam Turbine Efficiency".Power Engineering.Archived fromthe originalon 18 September 2009.Retrieved12 September2010.

- Leyzerovich, Alexander (2005).Wet-steam Turbines for Nuclear Power Plants.PennWell Books.ISBN978-1-59370-032-4.

- Moran, Michael J; Shapiro, Howard N;Boettner, Daisie D;Bailey, Margaret B (2010).Fundamentals of Engineering Thermodynamics.John Wiley & Sons.ISBN978-0-470-49590-2.

- Nag, PK (2002).Power Plant Engineering.Tata McGraw-Hill Education.ISBN978-0-07-043599-5.

- Parsons, Charles A(1911)..Cambridge University Press.

- O'Connor, JJ; Robertson, EF (1999)."Heron of Alexandria".The MacTutor History of Mathematics.

- Sanders, William P (2004).Turbine Steam Path: Mechanical Design and Manufacture.Vol. III a. PennWell.ISBN9781628702989.

- Stodola, A(2013) [1924].Dampf- und Gasturbinen. Mit einem Anhang über die Aussichten der Wärmekraftmaschinen[Steam and Gas Turbines: With an appendix on the prospective use as heat engines] (in German) (Supplement to the 5th ed.). Springer-Verlag.ISBN978-3-642-50854-7.

- Stodola, Aurel(1927).Steam and Gas Turbines: With a Supplement on The Prospects of the Thermal Prime Mover.McGraw-Hill.

- Stodola, Aurel;Loewenstein, Louis Centennial (1945).Steam and gas turbines: with a supplement on The prospects of the thermal prime mover.P Smith.

- Streeter, Tony (2007). "Testing the Limit".Steam Railway Magazine(336).

- Tamarin, Y (2002).Protective Coatings for Turbine Blades.ASM International.ISBN978-1-61503-070-5.

- Whitaker, Jerry C (2006).AC Power Systems Handbook(Third ed.). Taylor & Francis.ISBN978-0-8493-4034-5.

Further reading

[edit]- Cotton, KC (1998).Evaluating and Improving Steam Turbine Performance.Cotton Fact.

- Johnston, Ian (2019). "The Rise of the Brown-Curtis Turbine". In Jordan, John (ed.).Warship 2019.Oxford: Osprey Publishing. pp. 58–68.ISBN978-1-4728-3595-6.

- Thurston, RH (1878).A History of the Growth of the Steam Engine.New York: D Appleton and Co.

- Traupel, W (1977).Thermische Turbomaschinen(in German).Springer Verlag:Berlin, Heidelberg, New York.

- Waliullah, Noushad (2017). "An overview of Concentrated Solar Power (CSP) technologies and its opportunities in Bangladesh".2017 International Conference on Electrical, Computer and Communication Engineering (ECCE).CUET. pp. 844–849.doi:10.1109/ECACE.2017.7913020.ISBN978-1-5090-5627-9.S2CID42153522.

External links

[edit]- "Steam Turbine", The Engineer Guy[1]

- Steam Turbines: A Book of Instruction for the Adjustment and Operation of the Principal Types of this Class of Prime Moversby Hubert E Collins

- Steam Turbine Construction at Mike's Engineering WondersArchived2021-02-26 at theWayback Machine

- Tutorial: "Superheated Steam"

- Flow Phenomenon in Steam Turbine Disk-Stator Cavities Channeled by Balance Holes

- Guide to the Test of a 100 K.W. De Laval Steam Turbine with an Introduction on the Principles of Designcirca 1920

- Extreme Steam- Unusual Variations on The Steam Locomotive

- Interactive Simulationof 350MW Steam Turbine with Boiler developed byThe University of Queensland,in Brisbane Australia

- "Super-Steam...An Amazing Story of Achievement"Popular Mechanics,August 1937