Strandflat

Strandflat(Norwegian:strandflate[1]) is a landform typical of theNorwegiancoast consisting of a flattisherosion surfaceon the coast and near-coastseabed.In Norway, strandflats provide room for settlements andagriculture,constituting importantcultural landscapes.[1]The shallow and protected waters of strandflats are valued fishing grounds that provide sustenance to traditional fishing settlements.[1]Outside Norway proper, strandflats can be found in other high-latitude areas, such asAntarctica,Alaska,theCanadian Arctic,theRussian Far North,Greenland,Svalbard,SwedenandScotland.

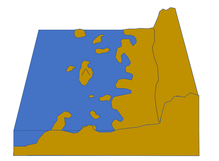

The strandflats are usually bounded on the landward side by a sharp break in slope, leading to mountainous terrain orhigh plateaux.On the seaward side, strandflats end at submarine slopes.[2][3]Thebedrocksurface of strandflats is uneven and tilts gently towards the sea.[3]

The concept of a strandflat was introduced in 1894 by Norwegian geologistHans Reusch.[4][5]

Norwegian strandflat[edit]

Characteristics[edit]

Strandflats are not fully flat and may display some local relief, meaning that it is usually not possible to assign them a precise elevation above sea level.[6]The Norwegian strandflats may go from 70–60 metres (230–200 ft) above sea level to 40–30 metres (131–98 ft) below sea level.[1]The undulations in the strandflat relief may result in an irregular coastline withskerries,small embayments and peninsulas.[2]

The width of the strandflat varies from a few kilometers to 50 km and occasionally reaching up to 80 km in width.[1][6]From land to sea the strandflat can be subdivided into the following zones: the supramarine zone, the skjærgård (skerry archipelago), and the submarine zone. Residual mountains surrounded by the strandflat are calledrauks.[7]

On the landward side, the strandflat often terminates abruptly with the beginning of a steep slope that separates it from higher or more uneven terrain.[2]In some locations this sharp boundary is lacking and the landward end of strandflat is diffuse.[8]On the seaward side, the strandflat continues underwater down to depths of 30 to 60 metres (98 to 197 ft), where a steep submarine slope separates it from older low reliefpaleic surfaces.These paleic surfaces are known as bankflat, and make up much of thecontinental shelf.[2]At some locations, the landward end of the strandflat or the region slightly above containsrelictsea cavespartly filled with sediments that predate thelast glacial period.These caves lie near thepost-glacial marine limitor above it.[3]

Overall, strandflats inNordlandare larger and flatter than those ofWestern Norway.[8]Also in Nordland, many strandflats are found next to activeseismic faults.[9]

Geological origin[edit]

Despite being together withfjordsthe most studied coastal landform in Norway,[10]as of 2013 there is no consensus as to the origin of strandflats.[5]An analysis of the literature shows that during the course of the 20th century, explanations for the strandflat shifted from involving one or two processes to including many more. Thus most modern explanations are ofpolygenetictype.[11]Grand-scale observations on the distribution of strandflats tend to favour an origin in connection to theQuaternary glaciations,while in-detail studies have led scholars to argue that strandflats have been shaped bychemical weatheringduring theMesozoic.According to this second view, the weathered surface would then have been buried in sediments to befreedfrom this cover duringLate Neogenefor a final reshaping by erosion.[12]Hans Holtedahlregarded the strandflats as modified paleic surfaces, conjecturing that paleic surfaces dipping gently to the sea would favoured strandflat formation.[8]

In his original description, Reusch regarded the strandflat as originating frommarine abrasionprior to glaciation,[5][A]but adding that some levelling could have been caused by non-marine erosion.[11]In his view, the formation of the strandflat preceded thefjords of Norway.[13]Years later, in 1919,Hans Ahlmannassumed the strandflat formed by erosion on land towards abase level.[5]In the mid-20th century, W. Evers argued in a series of publications that the strandflat was a low-erosion surface formed on land as part of a stepped sequence (piedmonttreppen) that included thePaleic surfaces.This idea was refuted byOlaf Holtedahl,who noted that the position of the surfaces were not that of a piedmonttreppen.[14][B]

Frost weathering, glaciers and sea ice[edit]

The Arctic explorerFritjof Nansenagreed with Reusch that marine influences formed the strandflat, but added in 1922 thatfrost weatheringwas also of key importance.[5][13]Nansen discarded ordinary marine abrasion as an explanation for the formation of the strandflat, as he noted that much of the strandflat lay in areas protected from major waves.[7]In his analysis, Nansen argued that the strandflat formed after the fjords of Norway had dissected the landscape. This, he argued, facilitated marine erosion by creating more coast and by creating nearbysediment sinksfor eroded material.[13]

In 1929,Olaf Holtedahlfavoured a glacial origin for the strandflat, an idea that was picked up by his sonHans Holtedahl.Hans Holtedahl and E. Larsen went on to argue in 1985 for an origin in connection to the Quaternary glaciations with material loosened byfrost weathering,andsea-icetransporting loose material andmaking the relief flat.[4]Tormod Klemsdal added in 1982 thatcirque glacierscould have made minor contributions in "widening, levelling and splitting the strandflat".[11][C]

Deep weathering and antiquity[edit]

Contrary to the glacial andperiglacialhypotheses,Julius Büdeland Jean-Pierre Peulvast regardweatheringof rock intosaproliteas important in shaping the strandflat. Büdel held that weathering took place in a distant past with tropical and sub-tropical climates, while Peulvast considered that present-day conditions and a lack of glaciation were enough to produce the weathering. As such, Peulvast considered the saprolite found in the strandflat, and the weathering that produced it, to predate theLast glacial periodand possibly theQuaternary glaciations.[4]For Büdel, the strandflat was asurface shaped by weatheringdotted withinselbergs.[5]

In 2013, Odleiv and co-workers put forward a mixed origin for the strandflat ofNordland.They argue that this strandflat in northern Norway could represent the remnants of a weatheredpeneplainofTriassicage[D]that was buried in sediment for long time before made flat again by erosion inPlioceneandPleistocenetimes.[5]A 2017 study concerningradiometric datingofillite,a clay formed by weathering, is interpreted to indicate that the strandflat atBømloinWestern Norwaywas weatheredc.210 million years ago duringLate Triassictimes.[12]Haakon Fossen and co-workers disagree with this view citingthermochronologystudies to claim that the strandflat in Western Norway was still covered by sedimentary rock in the Triassic and did only got free of its sedimentary cover in the Jurassic. Same authors note that movement ofgeological faultsin the Late Mesozoic imply the strandflats of Western Norway took their final shape after theLate Jurassicor else they would occur at various heights above sea level.[18]A similar opinion is expressed by Hans Holtedahl who wrote that "[t]he strandflat must have formed later the main (Tertiary)uplift of the Scandinavian landmass".[8]To this Holtedahl added that inTrøndelagbetween Nordland and Western Norway the strandflat could be a surface formed before the Jurassic, then buried in sediments and at some point freed from this cover.[8]In the understanding of Tormod Klemsdal strandflats may be old surfaces shaped by deep weathering that escaped theupliftthat affected theScandinavian Mountainsfurther east.[2]

The strandflat at Bømlo is considered by Ola Fredin and co-workers to be equivalent to the sediment-capped top ofUtsira Highoffshore west ofStavanger.[12]This view is also disputed by Haakon Fossen and co-workers who state that thebasementsurface under the northernNorth Seaformednot at a single time.[18]

Outside Norway[edit]

Strandflats have been identified in high-latitude areas such as the coast ofAlaska,Arctic Canada,Greenland,Svalbard,Novaya Zemlya[2]andTaymyr Peninsula[2]in Russia and the western coasts ofSwedenandScotland.[1][6][19]These strandflats are usually smaller than those in Norway.[12]

InAntarcticastrandflats can be found in theAntarctic Peninsula[12]as well as in theSouth Shetland Islands.[6]In addition there have been mentions of strandflats inSouth Georgia Island.[20]

InRobert Islandin the South Shetland Islands raised strandflats show that the island has been subject to a relative change in sea level.[21]Raisedshore platformscorresponding to strandflats have also been identified in Scotland'sHebrides.Possibly these formed inPliocenetimes and were later modified by theQuaternary glaciations.[22]

Gallery[edit]

-

Aerial view of the strandflat atBømlo

-

Aerial view of the strandflat atGoddo islandnear Bømlo

-

View of the strandflat at Helgeland from the mountain Dønnesfjellet in Dønna. A number ofraukscan be seen, from left:Træna,Lovunda, Selvær, Nesøya,Hestmona,Rødøyløva andLurøyfjellet,all landmarks on the Norwegian coast.

Explanatory footnotes[edit]

- ^American geographersWilliam Morris DavisandDouglas Wilson Johnsonsupported the view that marine erosion created the strandflat.[11]

- ^Later in 2000Karna Lidmar-Bergström,Cliff Ollierand Jan R. Sulebak did describe the Paleic surface as composed of a sequence of steps but did so only for the upper parts.[15]

- ^Cirquesin the southern half of Norway can be found both near sea level and at 2,000 m.[16]

- ^Remnants of a peneplain formed inTriassictimes do also exist insouthwestern Sweden.[17]

Citations[edit]

- ^abcdefBryhni, Inge (2018-05-16)."strandflate".InHelle, Knut(ed.).Store norske leksikon(in Norwegian). Oslo: Kunnskapsforlaget.

- ^abcdefgKlemsdal, Tormod (2005). "Strandflat". In Schwartz, Maurice L. (ed.).Encyclopedia of Coastal Science.Encyclopedia of Earth Sciences Series. pp. 914–915.ISBN978-1-4020-3880-8.

- ^abcCorner, Geoffrey (2004). "Scandes Mountains". InSeppälä, Matti(ed.).The Physical Geography of Fennoscandia.Oxford University Press. pp. 240–254.ISBN978-0-19-924590-1.

- ^abcLidmar-Bergström, K.;Olsson, S.; Roaldset, E. (1999). "Relief features and palaeoweathering remnants in formerly glaciated Scandinavian basement areas". In Thiry, Médard; Simon-Coinçon, Régine (eds.).Palaeoweathering, Palaeosurfaces and Related Continental Deposits.Special publication of the International Association of Sedimentologists. Vol. 27. Blackwell Science Ltd. pp. 275–301.ISBN0-632-05311-9.

- ^abcdefgOlesen, Odleiv; Kierulf, Halfdan Pascal; Brönner, Marco; Dalsegg, Einar; Fredin, Ola; Solbakk, Terje (2013). "Deep weathering, neotectonics and strandflat formation in Nordland, northern Norway".Norwegian Journal of Geology.93:189–213.

- ^abcdDawson, Alasdair D. (2004). "Strandflat". InGoudie, A.S.(ed.).Encyclopedia of Geomorphology.Routledge. pp. 345–347.

- ^abMotrøen, Terje (2000).Strandflatens dannelse – kystlandskapet som spiser seg inn i landblokken(PDF)(Report) (in Norwegian).Høgskolen i Hedmark.ISBN82-7671-104-9.RetrievedSeptember 6,2017.

- ^abcdeHoltedahl, Hans(1998)."The Norwegian strandflat puzzle"(PDF).Norsk Geologisk Tidsskrift.78:47–66.

- ^Setså, Ronny (2018)."Mange jordskjelv på strandflaten".geoforskning.no(in Norwegian).RetrievedApril 16,2018.

- ^Klemsdal, Tormod (2010). "Norway". In Bird, Eric C.F. (ed.).Encyclopedia of the World‘s Coastal Landforms.Springer Reference. Springer. pp. 571–579.ISBN978-1-4020-8638-0.

- ^abcdKlemsdal, Tormod (1982). "Coastal classification and the coast of Norway".Norwegian Journal of Geography.36(3): 129–152.doi:10.1080/00291958208552078.

- ^abcdeFredin, Ola; Viola, Giulio; Zwingmann, Horst; Sørlie, Ronald; Brönner, Marco; Lie, Jan-Erik; Margrethe Grandal, Else; Müller, Axel; Margeth, Annina; Vogt, Christoph; Knies, Jochen (2017)."The inheritance of a Mesozoic landscape in western Scandinavia".Nature.8:14879.Bibcode:2017NatCo...814879F.doi:10.1038/ncomms14879.PMC5477494.PMID28452366.

- ^abc"Nansen og den norske strandflaten".ngu.no(in Norwegian).Norwegian Geological Survey.October 25, 2011.RetrievedSeptember 6,2017.

- ^Holtedahl, Olaf(1965). "The South-Norwegian Piedmonttreppe of W. Evers".Norsk Geografisk Tidsskrift.20(3–4): 74–84.doi:10.1080/00291956508551831.

- ^Lidmar-Bergström, Karna;Ollier, C.D.;Sulebak, J.R. (2000). "Landforms and uplift history of southern Norway".Global and Planetary Change.24(3): 211–231.Bibcode:2000GPC....24..211L.doi:10.1016/S0921-8181(00)00009-6.

- ^Hall, Adrian M.; Ebert, Karin; Kleman, Johan; Nesje, Atle; Ottesen, Dag (2013). "Selective glacial erosion on the Norwegian passive margin".Geology.41(12): 1203–1206.Bibcode:2013Geo....41.1203H.doi:10.1130/g34806.1.

- ^Lidmar-Bergström, Karna(1993). "Denudation surfaces and tectonics in the southernmost part of the Baltic Shield".Precambrian Research.64(1–4): 337–345.Bibcode:1993PreR...64..337L.doi:10.1016/0301-9268(93)90086-h.

- ^abFossen, Haakon; Ksienzyk, Anna K.; Jacobs, Joachim (2017)."Correspondence: Challenges with dating weathering products to unravel ancient landscapes".Nature Communications.8(1): 1502.Bibcode:2017NatCo...8.1502F.doi:10.1038/s41467-017-01457-9.PMC5686066.PMID29138403.

- ^Asklund, B. (1928). "Strandflaten på Sveriges Västkust".Geologiska Föreningen i Stockholm Förhandlingar(in Swedish).50(4): 801–810.doi:10.1080/11035897.1928.9626360.

- ^Chalmers, M.; Clapperton, M.A. (1970).Geomorhpology of the Strombness Bay — Cumberland Bay area, South Georgia(PDF)(Report). British Antarctic Survey Scientific Reports. Vol. 70. pp. 1–25.RetrievedJanuary 29,2018.

- ^Serrano, Enrique; López-Martínez, Jerónimo (1997)."Geomorfología de la península Coppermine, isla Robert, islas Shetland del Sur, Antártica"(PDF).Serie Científica(in Spanish).47:19–29.

- ^Dawson, Alastrair G.; Dawson, Sue; Cooper, J. Andrew G.; Gemmell, Alastair; Bates, Richard (2013). "A Pliocene age and origin for the strandflat of the Western Isles of Scotland: a speculative hypothesis".Geological Magazine.150(2): 360–366.Bibcode:2013GeoM..150..360D.doi:10.1017/S0016756812000568.S2CID130965005.

General literature[edit]

- Holtedahl, Hans(1959). "Den norske strandflate. Med særlig henblikk på dens utvikling i kystområdene på Møre".Norwegian Journal of Geography.16:285–385.

- Nansen, Fridtjof(1904). "The Bathymetrical Features of the North Polar Seas". In Nansen F. (ed.):The Norwegian North Polar Expedition 1893–1896. Scientific results,Vol IV. J. Dybwad, Christiania, 1–232.

- Reusch, Hans(1894).Strandflaten, et nyt træk i Norges geografi.Norges geologiske undersokelse, 14, 1–14.