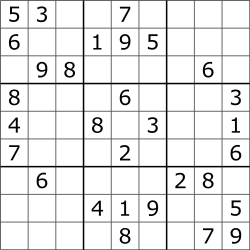

Sudoku

Sudoku(/suːˈdoʊkuː,-ˈdɒk-,sə-/;Japanese:Sổ độc,romanized:sūdoku,lit. 'digit-single'; originally calledNumber Place)[1]is alogic-based,[2][3]combinatorial[4]number-placementpuzzle.In classic Sudoku, the objective is to fill a 9 × 9 grid with digits so that each column, each row, and each of the nine 3 × 3 subgrids that compose the grid (also called "boxes", "blocks", or "regions" ) contains all of the digits from 1 to 9. The puzzle setter provides a partially completed grid, which for awell-posedpuzzle has a single solution.

French newspapers featured variations of the Sudoku puzzles in the 19th century, and the puzzle has appeared since 1979 inpuzzle booksunder the name Number Place.[5]However, the modern Sudoku only began to gain widespread popularity in 1986 when it was published by the Japanese puzzle companyNikoliunder the name Sudoku, meaning "single number".[6]It first appeared in a U.S. newspaper, and thenThe Times(London), in 2004, thanks to the efforts ofWayne Gould,who devised acomputer programto rapidly produce unique puzzles.

History[edit]

Predecessors[edit]

Number puzzles appeared in newspapers in the late 19th century, when French puzzle setters began experimenting with removing numbers frommagic squares.Le Siècle,a Paris daily, published a partially completed 9×9 magic square with 3×3 subsquares on November 19, 1892.[7]It was not a Sudoku because it contained double-digit numbers and required arithmetic rather than logic to solve, but it shared key characteristics: each row, column, and subsquare added up to the same number.

On July 6, 1895,Le Siècle'srival,La France,refined the puzzle so that it was almost a modern Sudoku and named itcarré magique diabolique('diabolical magic square'). It simplified the 9×9 magic square puzzle so that each row, column, andbroken diagonalscontained only the numbers 1–9, but did not mark the subsquares. Although they were unmarked, each 3×3 subsquare did indeed comprise the numbers 1–9, and the additional constraint on the broken diagonals led to only one solution.[8]

These weekly puzzles were a feature of French newspapers such asL'Écho de Parisfor about a decade, but disappeared about the time ofWorld War I.[9]

Modern Sudoku[edit]

The modern Sudoku was most likely designed anonymously byHoward Garns,a 74-year-old retired architect and freelance puzzle constructor fromConnersville, Indiana,and first published in 1979 byDell Magazinesas Number Place (the earliest known examples of modern Sudoku).[1]Garns' name was always present on the list of contributors in issues ofDell Pencil Puzzles and Word Gamesthat included Number Place and was always absent from issues that did not.[10]He died in 1989 before getting a chance to see his creation as a worldwide phenomenon.[10]Whether or not Garns was familiar with any of the French newspapers listed above is unclear.

The puzzle was introduced in Japan byMaki Kaji(Hạ trị chân khởi,Kaji Maki),president of the Nikoli puzzle company, in the paperMonthly Nikolistin April 1984[10]asSūji wa dokushin ni kagiru(Sổ tự は độc thân に hạn る),which can be translated as "the digits must be single", or as "the digits are limited to one occurrence" (In Japanese,dokushinmeans an "unmarried person" ). The name was later abbreviated toSudoku( sổ độc ), taking only the firstkanjiof compound words to form a shorter version.[10]"Sudoku" is a registered trademark in Japan[11]and the puzzle is generally referred to as Number Place(ナンバープレース,Nanbāpurēsu)or, more informally, a shortening of the two words, Num(ber) Pla(ce)(ナンプレ,Nanpure).In 1986, Nikoli introduced two innovations: the number of givens was restricted to no more than 32, and puzzles became "symmetrical" (meaning the givens were distributed inrotationally symmetric cells). It is now published in mainstream Japanese periodicals, such as theAsahi Shimbun.

Spread outside Japan[edit]

In 1997, Hong Kong judgeWayne Gouldsaw a partly completed puzzle in a Japanese bookshop. Over six years, he developed a computer program to produce unique puzzles rapidly.[5]Knowing that British newspapers have a long history of publishingcrosswordsand other puzzles, he promoted Sudoku toThe Timesin Britain, which launched it on November 12, 2004 (calling it Su Doku). The first letter toThe Timesregarding Su Doku was published the following day on November 13 from Ian Payn ofBrentford,complaining that the puzzle had caused him to miss his stop on thetube.[12]Sudoku puzzles rapidly spread to other newspapers as a regular feature.[5][13]

The rapid rise of Sudoku in Britain from relative obscurity to a front-page feature in national newspapers attracted commentary in the media and parody (such as whenThe Guardian'sG2section advertised itself as the first newspaper supplement with a Sudoku grid on every page).[14]Recognizing the different psychological appeals of easy and difficult puzzles,The Timesintroduced both, side by side, on June 20, 2005. From July 2005,Channel 4included a daily Sudoku game in theirteletextservice. On August 2, the BBC's program guideRadio Timesfeatured a weekly Super Sudoku with a 16×16 grid.

In the United States, the first newspaper to publish a Sudoku puzzle byWayne GouldwasThe Conway Daily Sun(New Hampshire), in 2004.[15]

The world's first live TV Sudoku show,Sudoku Live,was apuzzle contestfirst broadcast on July 1, 2005, onSky One.It was presented byCarol Vorderman.Nine teams of nine players (with one celebrity in each team) representing geographical regions competed to solve a puzzle. Each player had a hand-held device for entering numbers corresponding to answers for four cells. Phil Kollin ofWinchelsea, England,was the series grand prize winner, taking home over £23,000 over a series of games. The audience at home was in a separate interactive competition, which was won by Hannah Withey ofCheshire.

Later in 2005, theBBClaunchedSUDO-Q,agame showthat combined Sudoku with general knowledge. However, it used only 4×4 and 6×6 puzzles. Four seasons were produced before the show ended in 2007.

In 2006, a Sudoku website published songwriter Peter Levy's Sudoku tribute song,[16]but quickly had to take down theMP3 filedue to heavy traffic. The Japanese Embassy also nominated the song for an award, with Levy doing talks withSonyin Japan to release the song as a single.[17]

Sudoku software is very popular on PCs, websites, and mobile phones. It comes with many distributions ofLinux.The software has also been released on video game consoles, such as theNintendo DS,PlayStation Portable,theGame Boy Advance,Xbox Live Arcade,theNooke-book reader, Kindle Fire tablet, severaliPodmodels, and theiPhone.ManyNokiaphones also had Sudoku. In fact, just two weeks afterApple Inc.debuted the onlineApp Storewithin itsiTunes Storeon July 11, 2008, nearly 30 different Sudoku games were already in it, created by varioussoftware developers,specifically for the iPhone and iPod Touch. One of the most popular video games featuring Sudoku isBrain Age: Train Your Brain in Minutes a Day!.Critically and commercially well-received, it generated particular praise for its Sudoku implementation[18][19][20]and sold more than 8 million copies worldwide.[21]Due to its popularity, Nintendo made a secondBrain Agegame titledBrain Age2,which has over 100 new Sudoku puzzles and other activities.

In June 2008, an Australian drugs-related jury trial costing overA$1 million was aborted when it was discovered that four or five of the twelve jurors had been playing Sudoku instead of listening to the evidence.[22]

Variants[edit]

Variations of grid sizes or region shapes[edit]

Although the 9×9 grid with 3×3 regions is by far the most common, many other variations exist. Sample puzzles can be 4×4 grids with 2×2 regions; 5×5 grids withpentominoregions have been published under the name Logi-5; theWorld Puzzle Championshiphas featured a 6×6 grid with 2×3 regions and a 7×7 grid with sixheptominoregions and a disjoint region. Larger grids are also possible, or different irregular shapes (under various names such asSuguru,Tectonic,Jigsaw Sudokuetc.).The Timesoffers a 12×12-grid "Dodeka Sudoku" with 12 regions of 4×3 squares. Dell Magazines regularly publishes 16×16 "Number Place Challenger" puzzles (using the numbers 1–16 or the letters A-P). Nikoli offers 25×25 "Sudoku the Giant" behemoths. A 100×100-grid puzzle dubbed Sudoku-zilla was published in 2010.[23]

Mini Sudoku[edit]

Under the name "Mini Sudoku", a 6×6 variant with 3×2 regions appears in the American newspaperUSA Todayand elsewhere. The object is the same as that of standard Sudoku, but the puzzle only uses the numbers 1 through 6. A similar form, for younger solvers of puzzles, called "The Junior Sudoku", has appeared in some newspapers, such as some editions ofThe Daily Mail.

Imposing additional constraints[edit]

Another common variant is to add limits on the placement of numbers beyond the usual row, column, and box requirements. Often, the limit takes the form of an extra "dimension"; the most common is to require the numbers in the main diagonals of the grid to also be unique. The aforementioned "Number Place Challenger" puzzles are all of this variant, as are the Sudoku X puzzles inThe Daily Mail,which use 6×6 grids.

Killer sudoku[edit]

The killer sudoku variant combines elements of sudoku andkakuro.A killer sudoku puzzle is made up of 'cages', typically depicted by boxes outlined with dashes or colours. The sum of the numbers in a cage is written in the top left corner of the cage, and numbers cannot be repeated in a cage.

Other variants[edit]

Puzzles constructed from more than two grids are also common. Five 9×9 grids that overlap at the corner regions in the shape of aquincunxis known in Japan asGattai5 (five merged) Sudoku. InThe Times,The Age,andThe Sydney Morning Herald,this form of puzzle is known as Samurai Sudoku.The Baltimore Sunand theToronto Starpublish a puzzle of this variant (titled High Five) in their Sunday edition. Often, no givens are placed in the overlapping regions. Sequential grids, as opposed to overlapping, are also published, with values in specific locations in grids needing to be transferred to others.

A tabletop version of Sudoku can be played with a standard 81-card Set deck (seeSet game). A three-dimensional Sudoku puzzle was published inThe Daily Telegraphin May 2005.The Timesalso publishes a three-dimensional version under the name Tredoku. Also, a Sudoku version of theRubik's Cubeis namedSudoku Cube.

Many other variants have been developed.[24][25][26]Some are different shapes in the arrangement of overlapping 9×9 grids, such as butterfly, windmill, or flower.[27]Others vary the logic for solving the grid. One of these is "Greater Than Sudoku". In this, a 3×3 grid of the Sudoku is given with 12 symbols of Greater Than (>) or Less Than (<) on the common line of the two adjacent numbers.[10]Another variant on the logic of the solution is "Clueless Sudoku", in which nine 9×9 Sudoku grids are each placed in a 3×3 array. The center cell in each 3×3 grid of all nine puzzles is left blank and forms a tenth Sudoku puzzle without any cell completed; hence, "clueless".[27]Examples and other variants can be found in theGlossary of Sudoku.

Mathematics of Sudoku[edit]

This section refers to classic Sudoku, disregarding jigsaw, hyper, and other variants. A completed Sudoku grid is a special type ofLatin squarewith the additional property of no repeated values in any of the nine blocks (orboxesof 3×3 cells).[28]

The general problem of solving Sudoku puzzles onn2×n2grids ofn×nblocks is known to beNP-complete.[29]ManySudoku solving algorithms,such asbrute force-backtracking anddancing linkscan solve most 9×9 puzzles efficiently, butcombinatorial explosionoccurs asnincreases, creating practical limits to the properties of Sudokus that can be constructed, analyzed, and solved asnincreases. A Sudoku puzzle can be expressed as agraph coloringproblem.[30]The aim is to construct a 9-coloring of a particular graph, given a partial 9-coloring.

The fewest clues possible for a proper Sudoku is 17.[31]Tens of thousands of distinct Sudoku puzzles have only 17 clues.[32]

The number of classic 9×9 Sudoku solution grids is 6,670,903,752,021,072,936,960, or around6.67×1021.[33]The number of essentially different solutions, whensymmetriessuch as rotation, reflection, permutation, and relabelling are taken into account, is much smaller, 5,472,730,538.[34]

Unlike the number of complete Sudoku grids, the number of minimal 9×9 Sudoku puzzles is not precisely known. (A minimal puzzle is one in which no clue can be deleted without losing the uniqueness of the solution.) However, statistical techniques combined with a puzzle generator show that about (with 0.065% relative error) 3.10 × 1037minimal puzzles and 2.55 × 1025nonessentially equivalent minimal puzzles exist.[35]

Competitions[edit]

- The firstWorld Sudoku Championshipwas held inLucca,Italy,from March 10 to 11, 2006. The winner was Jana Tylová of theCzech Republic.[36]The competition included numerous variants.[37]

- The second World Sudoku Championship was held inPrague, Czech Republic,from March 28 to April 1, 2007.[38]The individual champion wasThomas Snyderof the US. The team champion was Japan.[39]

- The third World Sudoku Championship was held inGoa, India,from April 14 to 16, 2008. Thomas Snyder repeated as the individual overall champion and also won the first-ever Classic Trophy (a subset of the competition counting only classic Sudoku). The Czech Republic won the team competition.[40]

- The fourth World Sudoku Championship was held inŽilina,Slovakia,from April 24 to 27, 2009. After past champion Thomas Snyder of the US won the general qualification, Jan Mrozowski of Poland emerged from a 36-competitor playoff to become the new World Sudoku Champion. Host nation Slovakia emerged as the top team in a separate competition of three-membered squads.[41]

- The fifth World Sudoku Championship was held inPhiladelphia, Pennsylvania,from April 29 to May 2, 2010. Jan Mrozowski of Poland successfully defended his world title in the individual competition, while Germany won a separate team event. The puzzles were written by Thomas Snyder andWei-Hwa Huang,both past U.S. Sudoku champions.[42]

- The 12th World Sudoku Championship (WSC) was held inBangalore, India,from October 15 to 22, 2017. Kota Morinishi of Japan won the Individual WSC andChinawon the team event.[43]

- The 13th World Sudoku Championship took place in the Czech Republic.[44]

- In the United States,The Philadelphia InquirerSudoku National Championshiphas been held three times, each time offering a $10,000 prize to the advanced division winner and a spot on the U.S. National Sudoku Team traveling to the world championships. The winners of the event were Thomas Snyder (2007),[45]Wei-Hwa Huang (2008), and Tammy McLeod (2009).[46]In the 2009 event, the third-place finalist in the advanced division, Eugene Varshavsky, performed quite poorly onstage after setting a very fast qualifying time on paper, which caught the attention of organizers and competitors including past champion Thomas Snyder, who requested organizers reconsider his results due to a suspicion of cheating.[47]Following an investigation and a retest of Varshavsky, the organizers disqualified him and awarded the third-place to Chris Narrikkattu.[48]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^abGrossman, Lev (March 11, 2013)."The Answer Men".Time.New York. Archived fromthe originalon March 1, 2013.RetrievedMarch 4,2013.(registration required)

- ^Arnoldy, Ben. "Sudoku Strategies".The Christian Science Monitor.

- ^Schaschek, Sarah (March 22, 2006)."Sudoku champ's surprise victory".The Prague Post.Archived fromthe originalon August 13, 2006.RetrievedFebruary 18,2009.

- ^Gradwohl, Ronen; Naor, Moni; Pinkas, Benny; Rothblum, Guy N. (2007). "Cryptographic and Physical Zero-Knowledge Proof Systems for Solutions of Sudoku Puzzles". In Crescenzi, Pierluigi; Prencipe, Giuseppe; Pucci, Geppino (eds.).Fun with Algorithms, 4th International Conference, FUN 2007, Castiglioncello, Italy, June 3-5, 2007, Proceedings.Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Vol. 4475. Springer. pp. 166–182.doi:10.1007/978-3-540-72914-3_16.

- ^abcSmith, David (May 15, 2005)."So you thought Sudoku came from the Land of the Rising Sun..."The Observer.RetrievedJune 13,2008.

The puzzle gripping the nation actually began at a small New York magazine

- ^Hayes, Brian (2006). "Unwed Numbers".American Scientist.94(1): 12–15.doi:10.1511/2006.57.3475.

- ^Boyer, Christian (May 2006)."Supplément de l'article" Les ancêtres français du sudoku ""(PDF).Pour la Science(in French): 1–6. Archived fromthe original(PDF)on December 10, 2006.RetrievedAugust 3,2009.

- ^Boyer, Christian (2007)."Sudoku's French ancestors"(in French). (personal webpage). Archived fromthe originalon October 10, 2007.RetrievedAugust 3,2009.

- ^Malvern, Jack (June 3, 2006)."Les fiendish French beat us to Su Doku".Times Online.London.RetrievedSeptember 16,2006.

- ^abcdePegg, Ed Jr. (September 15, 2005)."Ed Pegg Jr.'s Math Games: Sudoku Variations".MAA Online.The Mathematical Association of America.RetrievedOctober 3,2006.

- ^"Reg. No. 5056856".Japanese Trademark 5056856.Japan Platform for Trademark Information.RetrievedOctober 3,2018.

- ^Payn, Ian (November 13, 2004)."Deep in thought".The Times.

- ^Devlin, Keith (January 28–29, 2012). "The Numbers Game (book review ofTaking Sudoku Seriouslyby Jason Rosenhouse et al.) ".The Wall Street Journal.Weekend Edition. p. C5.

- ^"G2, home of the discerning Sudoku addict".The Guardian.London. May 13, 2005.RetrievedSeptember 16,2006.

- ^"Correction attached to" Inside Japan's Puzzle Palace "".The New York Times.March 21, 2007.

- ^"Sudoku the song, by Peter Levy".Sudoku.org.uk.August 17, 2006.RetrievedOctober 5,2008.

- ^"Hit Song Has the Numbers".The Herald Sun.August 17, 2006.RetrievedOctober 5,2008.

- ^"Brain Age: Train Your Brain in Minutes a Day!".Gamerankings.com.

- ^"Brain Age:... Review".Gamespot.com.

- ^Harris, Craig (April 18, 2006)."Brain Age: Train Your Brain in Minutes a Day".IGN.RetrievedFebruary 8,2023.

- ^Thorsen, Tor (October 26, 2006)."Nintendo posts $456.6 million profit".GameSpot.RetrievedMarch 29,2013.

- ^Knox, Malcolm (June 11, 2008)."The game's up: jurors playing Sudoku abort trial".The Sydney Morning Herald.RetrievedJune 11,2008.

- ^Eisenhauer, William (2010).Sudoku-zilla.CreateSpace. p. 220.ISBN978-1-4515-1049-2.

- ^Snyder, Thomas; Huang, Wei-Hwa (2009).Mutant Sudoku.Puzzlewright Press.ISBN978-1-402765025.

- ^Conceptis, Puzzles (2013).Amazing Sudoku Variants.Puzzlewright.ISBN978-1454906520.OCLC700343731.

- ^Murali, A V (2014).A Collection of Fascinating Games and Puzzles.CreateSpace Independent Publishing.ISBN978-1500216429.OCLC1152132274.

- ^ab"Zahlenraetsel".janko.at.

- ^Keedwell, A. D. (November 2006). "Two remarks about Sudoku squares".The Mathematical Gazette.90(519): 425–430.doi:10.1017/s0025557200180234.JSTOR40378190.

- ^Yato, Takayuki; Seta, Takahiro (2003)."Complexity and completeness of finding another solution and its application to puzzles"(PDF).IEICE TRANSACTIONS on Fundamentals of Electronics, Communications and Computer Sciences.E86-A (5): 1052–1060. Archived fromthe original(PDF)on March 3, 2020.

- ^Lewis, R. (2015).A Guide to Graph Colouring: Algorithms and Applications.Springer.doi:10.1007/978-3-319-25730-3.ISBN978-3-319-25728-0.OCLC990730995.S2CID26468973.

- ^McGuire, G.; Tugemann, B.; Civario, G. (2014). "There is no 16-Clue Sudoku: Solving the Sudoku Minimum Number of Clues Problem".Experimental Mathematics.23(2): 190–217.arXiv:1201.0749.doi:10.1080/10586458.2013.870056.

- ^Royle, Gordon."Minimum Sudoku".Archived fromthe originalon November 26, 2006.RetrievedFebruary 28,2012.

- ^Sloane, N. J. A.(ed.)."Sequence A107739 (Number of (completed) sudokus (or Sudokus) of size n^2 X n^2)".TheOn-Line Encyclopedia of Integer Sequences.OEIS Foundation.

- ^Sloane, N. J. A.(ed.)."Sequence A109741 (Number of inequivalent (completed) n^2 X n^2 sudokus (or Sudokus))".TheOn-Line Encyclopedia of Integer Sequences.OEIS Foundation.

- ^Berthier, Denis (December 4, 2009)."Unbiased Statistics of a CSP – A Controlled-Bias Generator".In Elleithy, Khaled (ed.).Innovations in Computing Sciences and Software Engineering.Springer. pp. 165–70.Bibcode:2010iics.book.....S.doi:10.1007/978-90-481-9112-3.ISBN978-90-481-9111-6.RetrievedDecember 4,2009.

- ^"Sudoku title for Czech accountant".BBC News.March 11, 2006.RetrievedSeptember 11,2006.

- ^"World Sudoku Championship 2006 Instructions Booklet"(PDF).BBC News.Archived(PDF)from the original on June 10, 2006.RetrievedMay 24,2010.

- ^"Report on the 8th General Assembly of the World Puzzle Federation".World Puzzle Federation.October 30, 2006. Archived fromthe originalon September 26, 2007.RetrievedNovember 15,2006.

- ^"Thomas Snyder wins World Sudoku Championship".US Puzzle Team.March 31, 2007.RetrievedApril 18,2008.

- ^Harvey, Michael (April 17, 2008)."It's a puzzle but sun, sea, and beer can't compete with Sudoku for British team".TimesOnline.London.RetrievedApril 18,2008.

- ^Malvern, Jack (April 27, 2009)."Su Doku battle goes a little off the wall".TimesOnline.London.RetrievedApril 27,2009.

- ^"Pole, 23, repeats as Sudoku world champ".PhillyInquirer.May 2, 2009. Archived fromthe originalon May 5, 2010.RetrievedAugust 3,2013.

- ^"WSPC 2017 - Logic Masters India".wspc2017.logicmastersindia.com.

- ^"World Sudoku Championships | WPF".orldpuzzle.org.

- ^"Thomas Snyder, World Sudoku champion".The Philadelphia Inquirer.October 21, 2007.RetrievedOctober 21,2007.

- ^Shapiro, Howard (October 25, 2009)."Going for 2d, she wins 1st".The Philadelphia Inquirer.Archived fromthe originalon November 2, 2009.RetrievedAugust 3,2013.

- ^Timpane, John (October 27, 2009)."Possible cheating probed at Sudoku National Championship".The Philadelphia Inquirer.Archived fromthe originalon November 1, 2009.RetrievedAugust 3,2013.

- ^"3rd-place winner disqualified in Sudoku scandal".The Philadelphia Inquirer.November 24, 2009. Archived fromthe originalon November 27, 2009.RetrievedAugust 3,2013.

Further reading[edit]

- Delahaye, Jean-Paul (June 2006)."The Science Behind Sudoku"(PDF).Scientific American.294(6): 80–87.Bibcode:2006SciAm.294f..80D.doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0606-80.JSTOR26061494.PMID16711364.

- Provan, J. Scott (October 2009)."Sudoku: Strategy Versus Structure".American Mathematical Monthly.116(8): 702–707.doi:10.4169/193009709X460822.S2CID38433481.Also asUNC/STOR/08/04.