Syriac alphabet

| Syriac alphabet | |

|---|---|

Estrangela-styled alphabet | |

| Script type | Impureabjad

|

Time period | c. 1 AD – present |

| Direction | Right-to-left script |

| Languages | Aramaic(Classical Syriac,Western Neo-Aramaic,Assyrian Neo-Aramaic,Chaldean Neo-Aramaic,Turoyo,Christian Palestinian Aramaic),Arabic(Garshuni),Malayalam(Karshoni),Sogdian |

| Related scripts | |

Parent systems | Egyptian

|

Child systems | |

| ISO 15924 | |

| ISO 15924 | Syrc(135),Syriac

|

| Unicode | |

Unicode alias | Syriac |

| |

TheSyriac alphabet(ܐܠܦ ܒܝܬ ܣܘܪܝܝܐʾālep̄ bêṯ Sūryāyā[a]) is awriting systemprimarily used to write theSyriac languagesince the 1st century AD.[1]It is one of theSemiticabjadsdescending from theAramaic alphabetthrough thePalmyrene alphabet,[2]and shares similarities with thePhoenician,Hebrew,ArabicandSogdian,the precursor and a direct ancestor of the traditionalMongolian scripts.

Syriac is written from right to left in horizontal lines. It is acursivescript where most—but not all—letters connect within a word. There is noletter casedistinction between upper and lower case letters, though some letters change their form depending on their position within a word. Spacesseparateindividual words.

All 22 letters are consonants, although there are optional diacritic marks to indicate vowels andother features.In addition to the sounds of the language, the letters of the Syriac alphabet can be used to represent numbers in a system similar toHebrewandGreek numerals.

Apart from Classical Syriac Aramaic, the alphabet has been used to write other dialects and languages. Several Christian Neo-Aramaic languages fromTuroyoto theNortheastern Neo-Aramaicdialect ofSuret,oncevernaculars,primarily began to be written in the 19th century. TheSerṭāvariant specifically has been adapted to writeWestern Neo-Aramaic,previously written in thesquare Maalouli script,developed by George Rizkalla (Rezkallah), based on theHebrew alphabet.[3][4]Besides Aramaic, whenArabicbegan to be the dominant spoken language in theFertile Crescentafter theIslamic conquest,texts were often written in Arabic using the Syriac script as knowledge of the Arabic alphabet was not yet widespread; such writings are usually calledKarshuniorGarshuni(ܓܪܫܘܢܝ). In addition toSemitic languages,Sogdianwas also written with Syriac script, as well asMalayalam,which form was calledSuriyani Malayalam.

Alphabet forms[edit]

There are three major variants of the Syriac alphabet:ʾEsṭrangēlā,MaḏnḥāyāandSerṭā.

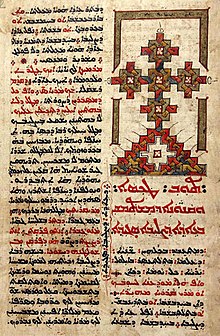

ClassicalʾEsṭrangēlā[edit]

The oldest and classical form of the alphabet isʾEsṭrangēlā[b](ܐܣܛܪܢܓܠܐ). The name of the script is thought to derive from theGreekadjectivestrongýlē(στρογγύλη,'rounded'),[5]though it has also been suggested to derive fromserṭā ʾewwangēlāyā(ܣܪܛܐ ܐܘܢܓܠܝܐ,'gospel character').[6]Although ʾEsṭrangēlā is no longer used as the main script for writing Syriac, it has received some revival since the 10th century. It is often used in scholarly publications (such as theLeiden Universityversion of thePeshitta), in titles, and ininscriptions.In some oldermanuscriptsand inscriptions, it is possible for any letter to join to the left, and older Aramaic letter forms (especially ofḥeṯand thelunatemem) are found. Vowel marks are usually not used withʾEsṭrangēlā,being the oldest form of the script and arising before the development of specialized diacritics.

East SyriacMaḏnḥāyā[edit]

The East Syriac dialect is usually written in theMaḏnḥāyā(ܡܲܕ݂ܢܚܵܝܵܐ, 'Eastern') form of the alphabet. Other names for the script includeSwāḏāyā(ܣܘܵܕ݂ܵܝܵܐ, 'conversational' or 'vernacular', often translated as 'contemporary', reflecting its use in writing modern Neo-Aramaic),ʾĀṯōrāyā(ܐܵܬ݂ܘܿܪܵܝܵܐ, 'Assyrian', not to be confused with the traditional name for theHebrew alphabet),Kaldāyā(ܟܲܠܕܵܝܵܐ, 'Chaldean'), and, inaccurately, "Nestorian" (a term that was originally used to refer to theChurch of the Eastin theSasanian Empire). The Eastern script resembles ʾEsṭrangēlā somewhat more closely than the Western script.

Vowels[edit]

The Eastern script uses a system of dots above and/or below letters, based on an older system, to indicate vowel sounds not found in the script:

- (

) A dot above and a dot below a letter represent[a],transliterated asaoră(calledܦܬ݂ܵܚܵܐ,pṯāḥā),

) A dot above and a dot below a letter represent[a],transliterated asaoră(calledܦܬ݂ܵܚܵܐ,pṯāḥā), - (

) Two diagonally-placed dots above a letter represent[ɑ],transliterated asāorâorå(calledܙܩܵܦ݂ܵܐ,zqāp̄ā),

) Two diagonally-placed dots above a letter represent[ɑ],transliterated asāorâorå(calledܙܩܵܦ݂ܵܐ,zqāp̄ā), - (

) Two horizontally-placed dots below a letter represent[ɛ],transliterated aseorĕ(calledܪܒ݂ܵܨܵܐ ܐܲܪܝܼܟ݂ܵܐ,rḇāṣā ʾărīḵāorܙܠܵܡܵܐ ܦܫܝܼܩܵܐ,zlāmā pšīqā;often pronounced[ɪ]and transliterated asiin the East Syriac dialect),

) Two horizontally-placed dots below a letter represent[ɛ],transliterated aseorĕ(calledܪܒ݂ܵܨܵܐ ܐܲܪܝܼܟ݂ܵܐ,rḇāṣā ʾărīḵāorܙܠܵܡܵܐ ܦܫܝܼܩܵܐ,zlāmā pšīqā;often pronounced[ɪ]and transliterated asiin the East Syriac dialect), - (

) Two diagonally-placed dots below a letter represent[e],transliterated asē(calledܪܒ݂ܵܨܵܐ ܟܲܪܝܵܐ,rḇāṣā karyāorܙܠܵܡܵܐ ܩܲܫܝܵܐ,zlāmā qašyā),

) Two diagonally-placed dots below a letter represent[e],transliterated asē(calledܪܒ݂ܵܨܵܐ ܟܲܪܝܵܐ,rḇāṣā karyāorܙܠܵܡܵܐ ܩܲܫܝܵܐ,zlāmā qašyā), - (ܘܼ) The letterwawwith a dot below it represents[u],transliterated asūoru(calledܥܨܵܨܵܐ ܐܲܠܝܼܨܵܐ,ʿṣāṣā ʾălīṣāorܪܒ݂ܵܨܵܐ,rḇāṣā),

- (ܘܿ) The letterwawwith a dot above it represents[o],transliterated asōoro(calledܥܨܵܨܵܐ ܪܘܝܼܚܵܐ,ʿṣāṣā rwīḥāorܪܘܵܚܵܐ,rwāḥā),

- (ܝܼ) The letteryōḏwith a dot beneath it represents[i],transliterated asīori(calledܚܒ݂ܵܨܵܐ,ḥḇāṣā),

- (

) A combination ofrḇāṣā karyā(usually) followed by a letteryōḏrepresents[e](possibly *[e̝]in Proto-Syriac), transliterated asēorê(calledܐܲܣܵܩܵܐ,ʾăsāqā).

) A combination ofrḇāṣā karyā(usually) followed by a letteryōḏrepresents[e](possibly *[e̝]in Proto-Syriac), transliterated asēorê(calledܐܲܣܵܩܵܐ,ʾăsāqā).

It is thought that the Eastern method for representing vowels influenced the development of theniqqudmarkings used for writing Hebrew.

In addition to the above vowel marks, transliteration of Syriac sometimes includesə,e̊or superscripte(or often nothing at all) to represent an original Aramaicschwathat became lost later on at some point in the development of Syriac. Some transliteration schemes find its inclusion necessary for showing spirantization or for historical reasons. Whether because its distribution is mostly predictable (usually inside a syllable-initial two-consonant cluster) or because its pronunciation was lost, both the East and the West variants of the alphabet traditionally have no sign to represent the schwa.

West SyriacSerṭā[edit]

The West Syriac dialect is usually written in theSerṭāorSerṭo(ܣܶܪܛܳܐ, 'line') form of the alphabet, also known as thePšīṭā(ܦܫܺܝܛܳܐ, 'simple'), 'Maronite' or the 'Jacobite' script (although the termJacobiteis considered derogatory). Most of the letters are clearly derived from ʾEsṭrangēlā, but are simplified, flowing lines. A cursivechancery handis evidenced in the earliest Syriac manuscripts, but important works were written in ʾEsṭrangēlā. From the 8th century, the simpler Serṭā style came into fashion, perhaps because of its more economical use ofparchment.

Vowels[edit]

The Western script is usually vowel-pointed, with miniature Greek vowel letters above or below the letter which they follow:

- (

) Capitalalpha(Α) represents[a],transliterated asaoră(ܦܬ݂ܳܚܳܐ,pṯāḥā),

) Capitalalpha(Α) represents[a],transliterated asaoră(ܦܬ݂ܳܚܳܐ,pṯāḥā), - (

) Lowercase alpha (α) represents[ɑ],transliterated asāorâorå(ܙܩܳܦ݂ܳܐ,Zqāp̄ā;pronounced as[o]and transliterated asoin the West Syriac dialect),

) Lowercase alpha (α) represents[ɑ],transliterated asāorâorå(ܙܩܳܦ݂ܳܐ,Zqāp̄ā;pronounced as[o]and transliterated asoin the West Syriac dialect), - (

) Lowercaseepsilon(ε) represents both[ɛ],transliterated aseorĕ,and[e],transliterated asē(ܪܒ݂ܳܨܳܐ,Rḇāṣā),

) Lowercaseepsilon(ε) represents both[ɛ],transliterated aseorĕ,and[e],transliterated asē(ܪܒ݂ܳܨܳܐ,Rḇāṣā), - (

) Capitaleta(H) represents[i],transliterated asī(ܚܒ݂ܳܨܳܐ,Ḥḇāṣā),

) Capitaleta(H) represents[i],transliterated asī(ܚܒ݂ܳܨܳܐ,Ḥḇāṣā), - (

) A combined symbol of capitalupsilon(Υ) and lowercaseomicron(ο) represents[u],transliterated asūoru(ܥܨܳܨܳܐ,ʿṣāṣā),

) A combined symbol of capitalupsilon(Υ) and lowercaseomicron(ο) represents[u],transliterated asūoru(ܥܨܳܨܳܐ,ʿṣāṣā), - Lowercaseomega(ω), used only in the vocative interjectionʾō(ܐܘّ, 'O!').

Summary table[edit]

The Syriac alphabet consists of the following letters, shown in their isolated (non-connected) forms. When isolated, the letterskāp̄,mīm,andnūnare usually shown with their initial form connected to their final form (seebelow). The lettersʾālep̄,dālaṯ,hē,waw,zayn,ṣāḏē,rēšandtaw(and, in early ʾEsṭrangēlā manuscripts, the lettersemkaṯ[7]) do not connect to a following letter within a word; these are marked with an asterisk (*).

| Letter | Sound Value (Classical Syriac) |

Numerical Value |

Phoenician Equivalent |

Imperial Aramaic Equivalent |

Hebrew Equivalent |

Arabic

Equivalent | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Translit. | ʾEsṭrangēlā (classical) |

Maḏnḥāyā (eastern) |

Serṭā (western) |

Unicode

(typing) |

Transliteration | IPA | |||||

| *ܐܠܦ | ʾĀlep̄*[c] | ܐ | ʾor null mater lectionis:ā |

[ʔ]or ∅ mater lectionis:[ɑ] |

1 | 𐤀 | 𐡀 | א | ا | |||

| ܒܝܬ | Bēṯ | ܒ | hard:b soft:ḇ(alsobh,vorβ) |

hard:[b] soft:[v]or[w] |

2 | 𐤁 | 𐡁 | ב | ب | |||

| ܓܡܠ | Gāmal | ܓ | hard:g soft:ḡ(alsog̱,gh,ġorγ) |

hard:[ɡ] soft:[ɣ] |

3 | 𐤂 | 𐡂 | ג | ج | |||

| *ܕܠܬ | Dālaṯ* | ܕ | hard:d soft:ḏ(alsodh,ðorδ) |

hard:[d] soft:[ð] |

4 | 𐤃 | 𐡃 | ד | د / ذ | |||

| *ܗܐ | Hē* | ܗ | h | [h] | 5 | 𐤄 | 𐡄 | ה | ه | |||

| *ܘܘ | Waw* | ܘ | consonant:w mater lectionis:ūorō (alsouoro) |

consonant:[w] mater lectionis:[u]or[o] |

6 | 𐤅 | 𐡅 | ו | و | |||

| *ܙܝܢ | Zayn* | ܙ | z | [z] | 7 | 𐤆 | 𐡆 | ז | ز | |||

| ܚܝܬ | Ḥēṯ | ܚ | ḥ(alsoH,kh,xorħ) | [ħ],[x]or[χ] | 8 | 𐤇 | 𐡇 | ח | ح | |||

| ܛܝܬ | Ṭēṯ | ܛ | ṭ(alsoTorţ) | [tˤ] | 9 | 𐤈 | 𐡈 | ט | ط | |||

| ܝܘܕ | Yōḏ | ܝ | consonant:y mater lectionis:ī(alsoi) |

consonant:[j] mater lectionis:[i]or[e] |

10 | 𐤉 | 𐡉 | י | ي | |||

| ܟܦ | Kāp̄ | ܟܟ | hard:k soft:ḵ(alsokhorx) |

hard:[k] soft:[x] |

20 | 𐤊 | 𐡊 | כ ך | ك | |||

| ܠܡܕ | Lāmaḏ | ܠ | l | [l] | 30 | 𐤋 | 𐡋 | ל | ل | |||

| ܡܝܡ | Mīm | ܡܡ | m | [m] | 40 | 𐤌 | 𐡌 | מ ם | م | |||

| ܢܘܢ | Nūn | ܢܢ | n | [n] | 50 | 𐤍 | 𐡍 | נ ן | ن | |||

| ܣܡܟܬ | Semkaṯ | ܣ | s | [s] | 60 | 𐤎 | 𐡎 | ס | ||||

| ܥܐ | ʿĒ | ܥ | ʿ | [ʕ][d] | 70 | 𐤏 | 𐡏 | ע | ع | |||

| ܦܐ | Pē | ܦ | hard:p soft:p̄(alsop̱,ᵽ,phorf) |

hard:[p] soft:[f] |

80 | 𐤐 | 𐡐 | פ ף | ف | |||

| *ܨܕܐ | Ṣāḏē* | ܨ | ṣ(alsoSorş) | [sˤ] | 90 | 𐤑 | 𐡑 | צ ץ | ص | |||

| ܩܘܦ | Qōp̄ | ܩ | q(alsoḳ) | [q] | 100 | 𐤒 | 𐡒 | ק | ق | |||

| *ܪܝܫ | Rēš* | ܪ | r | [r] | 200 | 𐤓 | 𐡓 | ר | ر | |||

| ܫܝܢ | Šīn | ܫ | š(alsosh) | [ʃ] | 300 | 𐤔 | 𐡔 | ש | س / ش | |||

| *ܬܘ | Taw* | ܬ | hard:t soft:ṯ(alsothorθ) |

hard:[t] soft:[θ] |

400 | 𐤕 | 𐡕 | ת | ت / ث | |||

Contextual forms of letters[edit]

| Letter

name |

ʾEsṭrangēlā(classical) | Maḏnḥāyā(eastern) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unconnected

final |

Connected

final |

Initial or

unconnected medial |

Unconnected

final |

Connected

final |

Initial or

unconnected medial | |

| ʾĀlep̄ | ||||||

| Bēṯ | ||||||

| Gāmal | ||||||

| Dālaṯ | ||||||

| Hē | ||||||

| Waw | ||||||

| Zayn | ||||||

| Ḥēṯ | ||||||

| Ṭēṯ | ||||||

| Yōḏ | ||||||

| Kāp̄ | ||||||

| Lāmaḏ | ||||||

| Mīm | ||||||

| Nūn | ||||||

| Semkaṯ | ||||||

| ʿĒ | ||||||

| Pē | ||||||

| Ṣāḏē | ||||||

| Qōp̄ | ||||||

| Rēš | ||||||

| Šīn | ||||||

| Taw | ||||||

Ligatures[edit]

Letter alterations[edit]

Matres lectionis[edit]

Three letters act asmatres lectionis:rather than being a consonant, they indicate a vowel.ʾālep̄(ܐ), the first letter, represents aglottal stop,but it can also indicate a vowel, especially at the beginning or the end of a word. The letterwaw(ܘ) is the consonantw,but can also represent the vowelsoandu.Likewise, the letteryōḏ(ܝ)represents the consonanty,but it also stands for the vowelsiande.

Majlīyānā[edit]

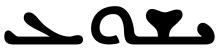

In modern usage, some alterations can be made to representphonemesnot represented inclassical phonology.A mark similar in appearance to atilde(~), calledmajlīyānā(ܡܲܓ̰ܠܝܼܵܢܵܐ), is placed above or below a letter in theMaḏnḥāyāvariant of the alphabet to change its phonetic value (see also:Geresh):

- Added belowgāmal:[ɡ]to[d͡ʒ](voiced palato-alveolar affricate)

- Added belowkāp̄:[k]to[t͡ʃ](voiceless palato-alveolar affricate)

- Added above or belowzayn:[z]to[ʒ](voiced palato-alveolar sibilant)

- Added abovešīn:[ʃ]to[ʒ]

Rūkkāḵāandqūššāyā[edit]

In addition to foreign sounds, a marking system is used to distinguishqūššāyā(ܩܘܫܝܐ,'hard' letters) fromrūkkāḵā(ܪܘܟܟܐ,'soft' letters). The lettersbēṯ,gāmal,dālaṯ,kāp̄,pē,andtaw,allstop consonants('hard') are able to be 'spirantized' (lenited) intofricative consonants('soft'). The system involves placing a single dot underneath the letter to give its 'soft' variant and a dot above the letter to give its 'hard' variant (though, in modern usage, no mark at all is usually used to indicate the 'hard' value):

| Name | Stop | Translit. | IPA | Name | Fricative | Translit. | IPA | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bēṯ (qšīṯā) | ܒ݁ | b | [b] | Bēṯ rakkīḵtā | ܒ݂ | ḇ | [v]or[w] | [v]has become[w]in most modern dialects. |

| Gāmal (qšīṯā) | ܓ݁ | g | [ɡ] | Gāmal rakkīḵtā | ܓ݂ | ḡ | [ɣ] | Usually becomes [j], [ʔ], or is not pronounced in modern Eastern dialects. |

| Dālaṯ (qšīṯā) | ܕ݁ | d | [d] | Dālaṯ rakkīḵtā | ܕ݂ | ḏ | [ð] | [d]is left unspirantized in some modern Eastern dialects. |

| Kāp̄ (qšīṯā) | ܟ݁ | k | [k] | Kāp̄ rakkīḵtā | ܟ݂ | ḵ | [x] | |

| Pē (qšīṯā) | ܦ݁ | p | [p] | Pē rakkīḵtā | ܦ݂ orܦ̮ | p̄ | [f]or[w] | [f]is not found in most modern Eastern dialects. Instead, it either is left unspirantized or sometimes appears as[w].Pēis the only letter in the Eastern variant of the alphabet that is spirantized by the addition of a semicircle instead of a single dot. |

| Taw (qšīṯā) | ܬ݁ | t | [t] | Taw rakkīḵtā | ܬ݂ | ṯ | [θ] | [t]is left unspirantized in some modern Eastern dialects. |

The mnemonicbḡaḏkp̄āṯ(ܒܓܕܟܦܬ) is often used to remember the six letters that are able to be spirantized (see also:Begadkepat).

In the East Syriac variant of the alphabet, spirantization marks are usually omitted when they interfere with vowel marks. The degree to which letters can be spirantized varies from dialect to dialect as some dialects have lost the ability for certain letters to be spirantized. For native words, spirantization depends on the letter's position within a word or syllable, location relative to other consonants and vowels,gemination,etymology,and other factors. Foreign words do not always follow the rules for spirantization.

Syāmē[edit]

Syriac uses two (usually) horizontal dots[f]above a letter within a word, similar in appearance todiaeresis,calledsyāmē(ܣܝ̈ܡܐ,literally 'placings', also known in some grammars by the Hebrew nameribbūi[רִבּוּי], 'plural'), to indicate that the word is plural.[8]These dots, having no sound value in themselves, arose before both eastern and western vowel systems as it became necessary to mark plural forms of words, which are indistinguishable from their singular counterparts in regularly-inflected nouns. For instance, the wordmalkā(ܡܠܟܐ,'king') is consonantally identical to its pluralmalkē(ܡܠܟ̈ܐ,'kings'); thesyāmēabove the wordmalkē(ܡܠܟ̈ܐ) clarifies its grammatical number and pronunciation. Irregular plurals also receivesyāmēeven though their forms are clearly plural: e.g.baytā(ܒܝܬܐ,'house') and its irregular pluralbāttē(ܒ̈ܬܐ,'houses'). Because of redundancy, some modern usage forgoessyāmēpoints when vowel markings are present.

There are no firm rules for which letter receivessyāmē;the writer has full discretion to place them over any letter. Typically, if a word has at least onerēš,thensyāmēare placed over therēšthat is nearest the end of a word (and also replace the single dot above it:ܪ̈). Other letters that often receivesyāmēare low-rising letters—such asyōḏandnūn—or letters that appear near the middle or end of a word.

Besides plural nouns,syāmēare also placed on:

- plural adjectives, including participles (except masculine plural adjectives/participles in theabsolute state);

- the cardinal numbers 'two' and the feminine forms of 11–19, though inconsistently;

- and certain feminine plural verbs: the 3rd person feminine plural perfect and the 2nd and 3rd person feminine plural imperfect.

Mṭalqānā[edit]

Syriac uses a line, calledmṭalqānā(ܡܛܠܩܢܐ,literally 'concealer', also known by theLatintermlinea occultansin some grammars), to indicate asilent letterthat can occur at the beginning or middle of a word.[9]In Eastern Syriac, this line is diagonal and only occurs above the silent letter (e.g.ܡܕ݂ܝܼܢ݇ܬܵܐ, 'city', pronouncedmḏīttā,not *mḏīntā,with themṭalqānāover thenūn,assimilatingwith thetaw). The line can only occur above a letterʾālep̄,hē,waw,yōḏ,lāmaḏ,mīm,nūn,ʿēorrēš(which comprise the mnemonicܥܡ̈ܠܝ ܢܘܗܪܐʿamlay nūhrā,'the works of light'). In Western Syriac, this line is horizontal and can be placed above or below the letter (e.g.ܡܕ݂ܺܝܢ̄ܬܳܐ, 'city', pronouncedmḏīto,not *mḏīnto).

Classically,mṭalqānāwas not used for silent letters that occurred at the end of a word (e.g.ܡܪܝmār[ī],'[my] lord'). In modernTuroyo,however, this is not always the case (e.g.ܡܳܪܝ̱mor[ī],'[my] lord').

Latin alphabet and romanization[edit]

In the 1930s, following the state policy for minority languages of theSoviet Union,aLatin alphabetfor Syriac wasdevelopedwith some material promulgated.[10]Although it did not supplant the Syriac script, the usage of the Latin script in the Syriac community has still become widespread because most of theAssyrian diasporais inEuropeand theAnglosphere,where the Latin alphabet is predominant.

In Syriac romanization, some letters are altered and would featurediacriticsand macrons to indicate long vowels, schwas anddiphthongs.The letters with diacritics and macrons are mostly upheld in educational or formal writing.[11]

| A | B | C | Ç | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | Ş | T | Ţ | U | V | X | Z | Ƶ | Ь |

The Latin letters below are commonly used when it comes totransliterationfrom the Syriac script toLatin:[14]

| A | Ā | B | C | D | Ḏ | E | Ē | Ë | F | G | H | Ḥ | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | Ō | P | Q | R | S | Š | Ṣ | T | Ṭ | U | Ū | V | W | X | Y | Z |

- Ā is used to denote a long "a" sound or [ɑː] as heard in "car".

- Ḏ is used to represent avoiced dental fricative[ð], the "th" sound as heard in "that".

- Ē is used to denote a long close-mid unrounded vowel, [eː].

- Ĕ is to represent an "eh" sound or [ɛ], as heard inNinwĕ

- Ḥ represents avoiceless pharyngeal fricative([ħ]), only upheld by Turoyo and Chaldean speakers.

- Ō represents a long "o" sound or [ɔː].

- Š is avoiceless postalveolar fricative([ʃ]), the English digraph "sh".

- Ṣ denotes anemphatic"s" or "thick s", [sˤ].

- Ṭ is an emphatic "t", [tˤ], as heard in the wordṭla( "three" ).

- Ū is used to represent an "oo" sound or theclose back rounded vowel[uː].

Sometimes additional letters may be used and they tend to be:

- Ḇmay be used in the transliteration ofbiblical Aramaicto show thevoiced bilabial fricativeallophonevalue ( "v" ) of the letterBēṯ.

- Īdenotes aschwasound, usually when transliterating biblical Aramaic.

- Ḵis utilized for thevoiceless velar fricative,[x], or the "kh" sound.

- Ṯis used to denote the "th" sound or thevoiceless dental fricative,[θ].

Unicode[edit]

The Syriac alphabet was added to theUnicodeStandard in September, 1999 with the release of version 3.0. Additional letters for Suriyani Malayalam were added in June, 2017 with the release of version 10.0.

Blocks[edit]

The Unicode block for Syriac is U+0700–U+074F:

| Syriac[1][2] Official Unicode Consortium code chart(PDF) | ||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | A | B | C | D | E | F | |

| U+070x | ܀ | ܁ | ܂ | ܃ | ܄ | ܅ | ܆ | ܇ | ܈ | ܉ | ܊ | ܋ | ܌ | ܍ | SAM | |

| U+071x | ܐ | ܑ | ܒ | ܓ | ܔ | ܕ | ܖ | ܗ | ܘ | ܙ | ܚ | ܛ | ܜ | ܝ | ܞ | ܟ |

| U+072x | ܠ | ܡ | ܢ | ܣ | ܤ | ܥ | ܦ | ܧ | ܨ | ܩ | ܪ | ܫ | ܬ | ܭ | ܮ | ܯ |

| U+073x | ܰ | ܱ | ܲ | ܳ | ܴ | ܵ | ܶ | ܷ | ܸ | ܹ | ܺ | ܻ | ܼ | ܽ | ܾ | ܿ |

| U+074x | ݀ | ݁ | ݂ | ݃ | ݄ | ݅ | ݆ | ݇ | ݈ | ݉ | ݊ | ݍ | ݎ | ݏ | ||

| Notes | ||||||||||||||||

The Syriac Abbreviation (a type ofoverline) can be represented with a special control character called theSyriac Abbreviation Mark(U+070F).

The Unicode block for Suriyani Malayalam specific letters is called the Syriac Supplement block and is U+0860–U+086F:

| Syriac Supplement[1][2] Official Unicode Consortium code chart(PDF) | ||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | A | B | C | D | E | F | |

| U+086x | ࡠ | ࡡ | ࡢ | ࡣ | ࡤ | ࡥ | ࡦ | ࡧ | ࡨ | ࡩ | ࡪ | |||||

| Notes | ||||||||||||||||

HTML code table[edit]

Note:HTML numeric character referencescan be in decimal format (&#DDDD;) or hexadecimal format (&#xHHHH;). For example, ܕ and ܕ (1813 in decimal) both represent U+0715 SYRIAC LETTER DALATH.

Ālep̄ bēṯ[edit]

| ܕ | ܓ | ܒ | ܐ |

| ܕ | ܓ | ܒ | ܐ |

|---|---|---|---|

| ܚ | ܙ | ܘ | ܗ |

| ܚ | ܙ | ܘ | ܗ |

| ܠ | ܟܟ | ܝ | ܛ |

| ܠ | ܟ | ܝ | ܛ |

| ܥ | ܣ | ܢܢ | ܡܡ |

| ܥ | ܤ | ܢ | ܡ |

| ܪ | ܩ | ܨ | ܦ |

| ܪ | ܩ | ܨ | ܦ |

| ܬ | ܫ | ||

| ܬ | ܫ |

Vowels and unique characters[edit]

| ܲ | ܵ |

| ܲ | ܵ |

|---|---|

| ܸ | ܹ |

| ܸ | ܹ |

| ܼ | ܿ |

| ܼ | ܿ |

| ̈ | ̰ |

| ̈ | ̰ |

| ݁ | ݂ |

| ݁ | ݂ |

| ܀ | ܂ |

| ܀ | ܂ |

| ܄ | ݇ |

| ܄ | ݇ |

See also[edit]

- Abjad

- Alphabet

- Aramaic alphabet

- Mandaic alphabet

- Mongolian script

- Sogdian alphabet

- Syriac language

- Syriac Malayalam

- Old Uyghur alphabet

- History of the alphabet

- List of writing systems

Notes[edit]

- ^Alsoܐܒܓܕ ܣܘܪܝܝܐʾabgad Sūryāyā.

- ^Also pronounced/transliteratedEstrangeloin Western Syriac.

- ^Also pronouncedʾĀlap̄orʾOlaf(ܐܳܠܰܦ) in Western Syriac.

- ^Among mostAssyrian Neo-Aramaicspeakers, the pharyngeal sound ofʿĒ(/ʕ/) is not pronounced as such; rather, it typically merges into the plain sound ofʾĀlep̄([ʔ]or ∅) orgeminatesa previous consonant.

- ^In the final position followingDālaṯorRēš,ʾĀlep̄takes the normal form rather than the final form in theMaḏnḥāyāvariant of the alphabet.

- ^In someSerṭāusages, thesyāmēdots are placed diagonally when they appear above the letterLāmaḏ.

References[edit]

- ^"Syriac alphabet".Encyclopædia Britannica Online.RetrievedJune 16,2012.

- ^P. R. Ackroyd, C. F. Evans (1975).The Cambridge History of the Bible: Volume 1, From the Beginnings to Jerome.Cambridge University Press. p. 26.ISBN9780521099738.

- ^Maissun Melhem (21 January 2010)."Schriftenstreit in Syrien"(in German). Deutsche Welle.Retrieved15 November2023.

Several years ago, the political leadership in Syria decided to establish an institute where Aramaic could be learned. Rizkalla was tasked with writing a textbook, primarily drawing upon his native language proficiency. For the script, he chose Hebrew letters.

- ^Oriens Christianus(in German). 2003. p. 77.

As the villages are very small, located close to each other, and the three dialects are mutually intelligible, there has never been the creation of a script or a standard language. Aramaic is the unwritten village dialect...

- ^Hatch, William(1946).An Album of Dated Syriac Manuscripts.Boston: The American Academy of Arts and Sciences, reprinted in 2002 by Gorgias Press. p. 24.ISBN1-931956-53-7.

- ^Nestle, Eberhard(1888).Syrische Grammatik mit Litteratur, Chrestomathie und Glossar.Berlin: H. Reuther's Verlagsbuchhandlung. [translated to English asSyriac grammar with bibliography, chrestomathy and glossary,by R. S. Kennedy. London: Williams & Norgate 1889. p. 5].

- ^Coakley, J. F. (2002).Robinson's Paradigms and Exercises in Syriac Grammar(5th ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 141.ISBN978-0-19-926129-1.

- ^Nöldeke, Theodorand Julius Euting (1880).Kurzgefasste syrische Grammatik.Leipzig: T.O. Weigel. [translated to English asCompendious Syriac Grammar,by James A. Crichton. London: Williams & Norgate 1904. 2003 edition. pp. 10–11.ISBN1-57506-050-7]

- ^Nöldeke, Theodorand Julius Euting (1880).Kurzgefasste syrische Grammatik.Leipzig: T.O. Weigel. [translated to English asCompendious Syriac Grammar,by James A. Crichton. London: Williams & Norgate 1904. 2003 edition. pp. 11–12.ISBN1-57506-050-7]

- ^Moscati, Sabatino, et al. The Comparative Grammar of Semitic Languages. Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden, Germany, 1980.

- ^S. P. Brock, "Three Thousand Years of Aramaic literature", in Aram,1:1 (1989)

- ^Friedrich, Johannes(1959)."Neusyrisches in Lateinschrift aus der Sowjetunion".Zeitschrift der Deutschen Morgenländischen Gesellschaft(in German) (109): 50–81.

- ^Polotsky, Hans Jakob(1961). "Studies in Modern Syriac".Journal of Semitic Studies.6(1): 1–32.doi:10.1093/jss/6.1.1.

- ^Syriac Romanization Table

- ^Nicholas Awde; Nineb Lamassu; Nicholas Al-Jeloo (2007).Aramaic (Assyrian/Syriac) Dictionary & Phrasebook: Swadaya-English, Turoyo-English, English-Swadaya-Turoyo.Hippocrene Books.ISBN978-0-7818-1087-6.

Sources[edit]

- Coakley, J. F. (2002).Robinson's Paradigms and Exercises in Syriac Grammar(5th ed.). Oxford University Press.ISBN978-0-19-926129-1.

- Hatch, William(1946).An Album of Dated Syriac Manuscripts.Boston: The American Academy of Arts and Sciences, reprinted in 2002 by Gorgias Press.ISBN1-931956-53-7.

- Kiraz, George(2015).The Syriac Dot: a Short History.Piscataway, NJ: Gorgias Press.ISBN978-1-4632-0425-9.

- Michaelis, Ioannis Davidis (1784).Grammatica Syriaca.

- Nestle, Eberhard(1888).Syrische Grammatik mit Litteratur, Chrestomathie und Glossar.Berlin: H. Reuther's Verlagsbuchhandlung. [translated to English asSyriac grammar with bibliography, chrestomathy and glossary,by R. S. Kennedy. London: Williams & Norgate 1889].

- Nöldeke, Theodorand Julius Euting (1880).Kurzgefasste syrische Grammatik.Leipzig: T.O. Weigel. [translated to English asCompendious Syriac Grammar,by James A. Crichton. London: Williams & Norgate 1904. 2003 edition:ISBN1-57506-050-7].

- Phillips, George (1866).A Syriac Grammar.Cambridge: Deighton, Bell, & Co.; London: Bell & Daldy.

- Robinson, Theodore Henry (1915).Paradigms and Exercises in Syriac Grammar.Oxford University Press.ISBN0-19-926129-6.

- Rudder, Joshua.Learn to Write Aramaic: A Step-by-Step Approach to the Historical & Modern Scripts.n.p.: CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2011. 220 pp.ISBN978-1461021421Includes the Estrangela (pp. 59–113), Madnhaya (pp. 191–206), and the Western Serto (pp. 173–190) scripts.

- Segal, J. B.(1953).The Diacritical Point and the Accents in Syriac.Oxford University Press, reprinted in 2003 by Gorgias Press.ISBN1-59333-032-4.

- Thackston, Wheeler M.(1999).Introduction to Syriac.Bethesda, MD: Ibex Publishers, Inc.ISBN0-936347-98-8.

External links[edit]

- The Syriac alphabetatOmniglot.com

- The Syriac alphabetatAncientscripts.com

- Unicode Entity Codes for the Syriac Script

- Meltho Fonts for Syriac

- How to write Aramaic – learn the Syriac cursive scripts

- Aramaic and Syriac handwritingArchived2018-07-23 at theWayback MachineʾEsṭrangēlā(classical)

- Learn Assyrian (Syriac-Aramaic) OnLineMaḏnḥāyā(eastern)

- GNU FreeFontUnicode font family with Syriac range in its sans-serif face.

- Learn Syriac Latin AlphabetonWikiversity