Tamarind

| Tamarind | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Rosids |

| Order: | Fabales |

| Family: | Fabaceae |

| Subfamily: | Detarioideae |

| Tribe: | Amherstieae |

| Genus: | Tamarindus L. |

| Species: | T. indica

|

| Binomial name | |

| Tamarindus indica L. 1753

| |

| Synonyms[3][4][5] | |

| |

Tamarind(Tamarindus indica) is aleguminoustree bearing edible fruit that is indigenous totropical Africaand naturalized inAsia.[6]The genusTamarindusismonotypic,meaning that it contains only this species. It belongs to the familyFabaceae.

The tamarind tree produces brown, pod-likefruitsthat contain a sweet, tangy pulp, which is used in cuisines around the world. The pulp is also used intraditional medicineand as ametal polish.The tree's wood can be used forwoodworkingandtamarind seed oilcan be extracted from the seeds. Tamarind's tender young leaves are used inSouth IndianandFilipino cuisine.[7][8]Because tamarind has multiple uses, it is cultivated around the world intropicalandsubtropical zones.

Description

[edit]The tamarind is a long-living, medium-growthtree,which attains a maximumcrownheight of 25 metres (80 feet). The crown has an irregular,vase-shaped outline of densefoliage.The tree grows well in full sun. It prefersclay,loam,sandy,and acidic soil types, with a high resistance to drought and aerosol salt (wind-borne salt as found in coastal areas).[9][failed verification]

Theevergreenleaves are alternately arranged andpinnately lobed.The leaflets are bright green, elliptic-ovular,pinnatelyveined, and less than 5 centimetres (2 inches) in length. The branches droop from a single, centraltrunkas the tree matures, and are oftenprunedin agriculture to optimize tree density and ease of fruit harvest. At night, the leaflets close up.[9][failed verification]

As a tropical species, it is frost-sensitive. The pinnate leaves with opposite leaflets give a billowing effect in the wind. Tamarindtimberconsists of hard, dark redheartwoodand softer, yellowishsapwood.[10]

The tamarind flowers bloom (although inconspicuously), with red and yellow elongated flowers. Flowers are 2.5 cm (1 in) wide, five-petalled, borne in smallracemes,and yellow with orange or red streaks.Budsare pink as the foursepalsare pink and are lost when the flowerblooms.[11]

-

A tamarind seedling

-

Tamarind flower

-

Tamarind flowers

-

Tamarindusleaves and fruit pod

-

Tamarind tree on the site of the founding ofSanta Clara, Cuba

Fruit

[edit]

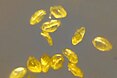

The fruit is anindehiscentlegume,sometimes called a pod,12 to 15 cm (4+1⁄2to 6 in) in length, with a hard, brown shell.[12][13][14]

The fruit has a fleshy, juicy, acidic pulp. It is mature when the flesh is coloured brown or reddish brown. The tamarinds of Asia have longer pods (containing six to 12 seeds), whereas African and West Indian varieties have shorter pods (containing one to six seeds). The seeds are somewhat flattened, and a glossy brown. The fruit is sweet and sour in taste.

History

[edit]Etymology

[edit]The name derives fromArabic:تمر هندي,romanizedtamr hindi,"Indiandate".[15]Several early medieval herbalists and physicians wrotetamar indi,medieval Latin use wastamarindus,andMarco Polowrote oftamarandi.

In Colombia, Nicaragua, Costa Rica, Ecuador, Cuba, the Dominican Republic, Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, Mexico, Peru, Puerto Rico, Venezuela, Italy, Spain, and throughout theLusosphere,it is calledtamarindo.In those countries it is often used to make thebeverage of the same name(oragua de tamarindo). In the Caribbean, tamarind is sometimes calledtamón.[citation needed]

Countries inSoutheast AsialikeIndonesiacall itasam jawa(Javanesesour fruit) or simplyasam,[16]andsukaerinTimor.[17]While in thePhilippines,it is calledsampalokorsampalocinFilipino,andsambaginCebuano.[18]Tamarind (Tamarindus indica) is sometimes confused with "Manila tamarind" (Pithecellobium dulce). While in the same taxonomic familyFabaceae,Manila tamarindis a different plant native to Mexico and known locally asguamúchili.

Taxonomy

[edit]Tamarindus indicais probablyindigenousto tropical Africa,[19]but has been cultivated for so long on the Indian subcontinent that it is sometimes reported to be indigenous there.[20]It grows wild in Africa in locales as diverse as Sudan,[20][citation needed]Cameroon, Nigeria, Kenya, Zambia, Somalia, Tanzania and Malawi. In Arabia, it is found growing wild in Oman, especiallyDhofar,where it grows on the sea-facing slopes of mountains. It reached South Asia likely through human transportation and cultivation several thousand years ago.[20][21]It is widely distributed throughout the tropics,[20]from Africa to South Asia.

In the 16th century, it was introduced to Mexico and Central America, and to a lesser degree to South America, by Spanish and Portuguese colonists, to the degree that it became a staple ingredient in the region's cuisine.[22]

As of 2006[update]India is the largest producer of tamarind.[23]The consumption of tamarind is widespread due to its central role in the cuisines of the Indian subcontinent, Southeast Asia, and the Americas, especially Mexico.[citation needed]

Uses

[edit] | |

| Nutritional value per 100 g (3.5 oz) | |

|---|---|

| Energy | 1,000 kJ (240 kcal) |

62.5 g | |

| Sugars | 57.4 |

| Dietary fiber | 5.1 g |

0.6 g | |

| Saturated | 0.272 g |

| Monounsaturated | 0.181 g |

| Polyunsaturated | 0.059 g |

2.8 g | |

| Tryptophan | 0.018 g |

| Lysine | 0.139 g |

| Methionine | 0.014 g |

| Vitamins | Quantity %DV† |

| Vitamin A equiv. | 0% 2 μg |

| Vitamin A | 30 IU |

| Thiamine (B1) | 36% 0.428 mg |

| Riboflavin (B2) | 12% 0.152 mg |

| Niacin (B3) | 12% 1.938 mg |

| Pantothenic acid (B5) | 3% 0.143 mg |

| Vitamin B6 | 4% 0.066 mg |

| Folate (B9) | 4% 14 μg |

| Choline | 2% 8.6 mg |

| Vitamin C | 4% 3.5 mg |

| Vitamin E | 1% 0.1 mg |

| Vitamin K | 2% 2.8 μg |

| Minerals | Quantity %DV† |

| Calcium | 6% 74 mg |

| Copper | 96% 0.86 mg |

| Iron | 16% 2.8 mg |

| Magnesium | 22% 92 mg |

| Phosphorus | 9% 113 mg |

| Potassium | 21% 628 mg |

| Selenium | 2% 1.3 μg |

| Sodium | 1% 28 mg |

| Zinc | 1% 0.1 mg |

| Other constituents | Quantity |

| Water | 31.40 g |

USDA Database;entry | |

| †Percentages estimated usingUS recommendationsfor adults,[24]except for potassium, which is estimated based on expert recommendation fromthe National Academies.[25] | |

Culinary

[edit]The fruit is harvested by pulling the pod from its stalk. A mature tree can produce up to 175 kilograms (386 pounds) of fruit per year.Veneer grafting,shield (T or inverted T) budding,andair layeringmay be used to propagate desirable cultivars. Such trees will usually fruit within three to four years if provided optimum growing conditions.[9]

The fruit pulp is edible. The hard green pulp of a young fruit is considered by many to be too sour, but is often used as a component of savory dishes, as apicklingagent or as a means of making certain poisonousyamsin Ghana safe for human consumption.[26]As the fruit matures it becomes sweeter and less sour (acidic) and the ripened fruit is considered more palatable. The sourness varies between cultivars and some sweet tamarind ones have almost no acidity when ripe. In Western cuisine, tamarind pulp is found inWorcestershire sauce,[27]HP Sauce,and some brands ofbarbecue sauce[28][29](especially in Australia, with the tamarind derived from Worcestershire sauce[30]).

Tamarind paste has many culinary uses including as a flavoring forchutneys,curries, and the traditionalsharbatsyrup drink.[31]Tamarind sweetchutneyis popular in India and Pakistan[32]as a dressing for many snacks and often served withsamosa.Tamarind pulp is a key ingredient in flavoring curries and rice in south Indian cuisine, in theChigalilollipop, inrasam,Koddeland in certain varieties ofmasala chai.

Across the Middle East, from theLevanttoIran,tamarind is used in savory dishes, notably meat-based stews, and often combined with dried fruits to achieve a sweet-sour tang.[33][34]

In the Philippines, the whole fruit is used as one of the souring agents of the sour soupsinigang(which can also use other sour fruits), as well as another type of soup calledsinampalukan(which also uses tamarind leaves).[35][8]The fruit pulp are also cooked in sugar and/or salt to makechampóy na sampalok(or simply "sampalok candy" ), a traditional tamarind candy.[36]Indonesia also has a similarly sour, tamarind-based soup dish calledsayur asem.Tamarind pulp mixed with liquid is also used in beverage astamarind juice.In Java, Indonesia, tamarind juice is known ases asemorgula asem,tamarind juice served withpalm sugarand ice as a fresh sour and sweet beverage.

In Mexico and the Caribbean, the pulp is diluted with water and sugared to make anagua frescadrink. It is widely used throughout all of Mexico for candy making, including tamarind mixed with chilli powder candy.

InSokoto,Nigeria,tamarind pulp is used to fix the color indyedleather products by neutralizing the alkali substances used in tanning.[37]

The leaves and bark are also edible, and the seeds can be cooked to make safe for consumption.[38]Blanched, tender tamarind leaves are used in aBurmese saladcalledmagyi ywet thoke(မန်ကျည်းရွက်သုပ်;lit. 'tamarind leaf salad'), a salad fromUpper Myanmarthat features tender blanched tamarind leaves, garlic, onions, roasted peanuts, and pounded dried shrimp.[39][40]

-

Vietnamese tamarind paste

-

Tamarind balls fromTrinidad and Tobago

Seed oil and kernel powder

[edit]Tamarind seed oil is made from the kernel of tamarind seeds.[41]The kernel is difficult to isolate from its thin but tough shell (ortesta). It has a similar consistency to linseed oil, and can be used to make paint or varnish.[42]

Tamarind kernel powder is used assizingmaterial for textile and jute processing, and in the manufacture of industrial gums and adhesives. It is de-oiled to stabilize its colour and odor on storage.[citation needed]

Folk medicine

[edit]Throughout Southeast Asia, the fruit of the tamarind is used as apoulticeapplied to the foreheads of people with fevers.[12]The fruit exhibitslaxativeeffects due to its high quantities ofmalic acid,tartaric acid,andpotassium bitartrate.Its use for the relief ofconstipationhas been documented throughout the world.[43][44]Extract of steamed and sun-dried old tamarind pulp in Java (asem kawa) are used to treat skin problems like rashes and irritation; it can also be ingested after dilution as anabortifacient.[16]

Woodworking

[edit]Tamarind wood is used to make furniture, boats (as perRumphius) carvings, turned objects such asmortars and pestles,chopping blocks, and other small specialty wood items likekrises.[16]Tamarind heartwood is reddish brown, sometimes with a purplish hue. The heartwood in tamarind tends to be narrow and is usually only present in older and larger trees. The pale yellow sapwood is sharply demarcated from the heartwood. Heartwood is said to be durable to very durable in decay resistance, and is also resistant to insects. Its sapwood is not durable and is prone to attack by insects and fungi as well asspalting.Due to its density and interlocked grain, tamarind is considered difficult to work. Heartwood has a pronounced blunting effect on cutting edges. Tamarind turns, glues, and finishes well. The heartwood is able to take a high natural polish.[45]

Metal polish

[edit]In homes and temples, especially inBuddhistAsian countries includingMyanmar,the fruit pulp is used to polish brass shrine statues and lamps, and copper, brass, and bronze utensils.[46]Tamarind containstartaric acid,a weak acid that can removetarnish.Lime,another acidic fruit, is used similarly.[20]

| Composition | Original | De-oiled |

|---|---|---|

| Oil | 7.6% | 0.6% |

| Protein | 7.6% | 19.0% |

| Polysaccharide | 51.0% | 55.0% |

| Crude fiber | 1.2% | 1.1% |

| Total ash | 3.9% | 3.4% |

| Acid insoluble ash | 0.4% | 0.3% |

| Moisture | 7.1% | |

| The fatty acid composition of the oil islinoleic46.5%,oleic27.2%, andsaturated fatty acids26.4%. The oil is usually bleached after refining. | ||

| Fatty acid | (%) Range reported |

|---|---|

| Lauric acid(C12:0) | tr-0.3 |

| Myristic acid(C14:0) | tr-0.4 |

| Palmitic acid(C16:0) | 8.7–14.8 |

| Stearic acid(C18:0) | 4.4–6.6 |

| Arachidic acid(C20:0) | 3.7–12.2 |

| Lignoceric acid(C24:0) | 4.0–22.3 |

| Oleic acid(C18:1) | 19.6–27.0 |

| Linoleic acid(18:2) | 7.5–55.4 |

| Linolenic acid(C18:3) | 2.8–5.6 |

Research

[edit]In hens, tamarind has been found to lower cholesterol in their serum, and in the yolks of the eggs they laid.[47][48]

In dogs, thetartaric acidof tamarind causesacute kidney injury,which can often be fatal.[49]

Lupanone,lupeol,catechins,epicatechin,quercetin,andisorhamnetinare present in the leafextract.[50]Ultra-high performance liquid chromatography analyses revealed that tamarind seeds contained catechin,procyanidin B2,caffeic acid,ferulic acid,chloramphenicol,myricetin,morin,quercetin,apigeninandkaempferol.[51]

Cultivation

[edit]Seeds can bescarifiedor briefly boiled to enhancegermination.They retain their germination capability for several months if kept dry.[citation needed]

The tamarind has long beennaturalizedin Indonesia, Malaysia, Sri Lanka, the Philippines, the Caribbean, and Pacific Islands. Thailand has the largest plantations of theASEANnations, followed by Indonesia, Myanmar, and the Philippines. In parts of Southeast Asia, tamarind is calledasam.[52]It is cultivated all over India, especially inMaharashtra,Chhattisgarh,Karnataka,Telangana,Andhra Pradesh,andTamil Nadu.Extensive tamarind orchards in India produce 250,000 tonnes (280,000 short tons) annually.[9]

In the United States, it is a large-scale crop introduced for commercial use (second in net production quantity only to India), mainly in southern states, notably south Florida, and as a shade tree, along roadsides, in dooryards and in parks.[53]

A traditional food plant in Africa, tamarind has the potential to improve nutrition, boost food security, foster rural development and support sustainable landcare.[54]In Madagascar, its fruit and leaves are a well-known favorite of thering-tailed lemur,providing as much as 50 percent of their food resources during the year if available.[55]

Horticulture

[edit]Throughout South Asia and the tropical world, tamarind trees are used as ornamental, garden, and cash crop plantings. Commonly used as a bonsai species in many Asian countries, it is also grown as an indoor bonsai in temperate parts of the world.[56]

References

[edit]- ^Rivers, M.C.; Mark, J. (2017)."Tamarindus indica".IUCN Red List of Threatened Species.2017:e.T62020997A62020999.doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2017-3.RLTS.T62020997A62020999.en.RetrievedNovember 19,2021.

- ^Speg.Anales Soc. Ci. Argent.82: 223 1916

- ^"Tamarindus indicaL. "The Plant List.Royal Botanic Gardens, Kewand theMissouri Botanical Garden.2013.RetrievedFebruary 28,2017.

- ^Quattrocchi U. (2012).CRC World Dictionary of Medicinal and Poisonous Plants: Common Names, Scientific Names, Eponyms, Synonyms, and Etymology.Boca Raton, Louisiana:CRC Press,Taylor & Francis Group.pp. 3667–3668.ISBN9781420080445.

- ^USDA;ARS;National Genetic Resources Program (February 10, 2005)."CavaraeaSpeg ".Germplasm Resources Information Network—(GRIN) [Online Database].National Germplasm Resources Laboratory,Beltsville, Maryland.RetrievedFebruary 28,2017.

- ^El-Siddig, K. (2006).Tamarind: Tamarindus Indica L.Crops for the Future.ISBN978-0-85432-859-8.

- ^Borah, Prabalika M. (April 27, 2018)."Here's what you can cook with tender tamarind leaves".The Hindu.

- ^abManalo, Lalaine (August 14, 2013)."Sinampalukang Manok".Kawaling Pinoy.RetrievedMarch 27,2021.

- ^abcd"Tamarind –Tamarindus indica– van Veen Organics ".van Veen Organics.Archived fromthe originalon February 14, 2014.RetrievedJune 4,2017.

- ^"Tamarind: a multipurpose tree".DAWN.COM.July 9, 2007.RetrievedJune 4,2017.

- ^"Tamarind".Plant Lexica.Archived fromthe originalon September 18, 2020.RetrievedJune 4,2017.

- ^abDoughari, J. H. (December 2006)."Antimicrobial Activity ofTamarindus indica".Tropical Journal of Pharmaceutical Research.5(2): 597–603.doi:10.4314/tjpr.v5i2.14637.

- ^"Fact Sheet:Tamarindus indica"(PDF).University of Florida.RetrievedJuly 22,2012.

- ^Christman, S."Tamarindus indica".FloriData.RetrievedJanuary 11,2010.

- ^T. F. Hoad, ed. (2003). "tamarind".The Concise Oxford Dictionary of English Etymology.Oxford University Press.doi:10.1093/acref/9780192830982.001.0001.ISBN9780191727153.

- ^abcHeyne, Karel(1913)."Tamarindua indica L.".De nuttige planten van Nederlandsch-Indië, tevens synthetische catalogus der verzamelingen van het Museum voor Technischeen Handelsbotanie te Buitenzorg(in Dutch).Butienzorg:Museum vor Economische Botanie & Ruygrok. pp. 232–5.

- ^"Asam Tree".nparks.gov.sg.National Parks of Singapore.RetrievedJanuary 14,2021.

- ^Polistico, Edgie (2017).Philippine Food, Cooking, & Dining Dictionary.Anvil Publishing, Inc.ISBN9786214200870.

- ^Diallo, BO; Joly, HI; McKey, D; Hosaert-McKey, M; Chevallier, MH (2007)."Genetic diversity ofTamarindus indicapopulations: Any clues on the origin from its current distribution? ".African Journal of Biotechnology.6(7).

- ^abcdeMorton, Julia F.(1987).Fruits of Warm Climates.Wipf and Stock Publishers. pp. 115–121.ISBN978-0-9653360-7-9.

- ^Popenoe, W. (1974).Manual of Tropical and Subtropical Fruits.Hafner Press. pp.432–436.

- ^Tamale, E.; Jones, N.; Pswarayi-Riddihough, I. (August 1995).Technologies Related to Participatory Forestry in Tropical and Subtropical Countries.World Bank Publications.ISBN978-0-8213-3399-0.

- ^El-Siddig; Gunasena; Prasad; Pushpakumara; Ramana; Vijayanand; Williams (2006).Tamarind, Tamarindus indica(PDF).Southampton Centre for Underutilised Crops.ISBN0854328599.Archived fromthe original(PDF)on September 1, 2012.

- ^United States Food and Drug Administration(2024)."Daily Value on the Nutrition and Supplement Facts Labels".FDA.Archivedfrom the original on March 27, 2024.RetrievedMarch 28,2024.

- ^National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Health and Medicine Division; Food and Nutrition Board; Committee to Review the Dietary Reference Intakes for Sodium and Potassium (2019). Oria, Maria; Harrison, Meghan; Stallings, Virginia A. (eds.).Dietary Reference Intakes for Sodium and Potassium.The National Academies Collection: Reports funded by National Institutes of Health. Washington, DC: National Academies Press (US).ISBN978-0-309-48834-1.PMID30844154.Archivedfrom the original on May 9, 2024.RetrievedJune 21,2024.

- ^El-Siddig, K. (2006).Tamarind:Tamarindus indicaL.Crops for the Future.ISBN9780854328598.

- ^"BBC Food:Ingredients—Tamarind recipes".BBC.RetrievedFebruary 23,2015.

- ^"Original Sweet & Thick BBQ Sauce - Products - Heinz®".www.heinz.com.RetrievedMarch 29,2024.

- ^"MasterFoods Barbecue Sauce 500mL Ingredients".

- ^"Barbecue sauce".Women's Weekly Food.May 31, 2010.RetrievedMarch 29,2024.

- ^Azad, Salim (2018). "Tamarindo—Tamarindus indica". In Sueli Rodrigues; Ebenezer de Oliveira Silva; Edy Sousa de Brito (eds.).Exotic Fruits.Academic Press. pp. 403–412.doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-803138-4.00055-1.ISBN978-0-12-803138-4.

- ^The Complete Asian Cookbook.Tuttle Publishing. 2006. p. 88.ISBN9780804837576.

- ^"Tamarind is the 'sour secret of Syrian cooking'".PRI. July 2014

- ^Phyllis Glazer; Miriyam Glazer; Joan Nathan."Georgian Chicken in Pomegranate and Tamarind Sauce Recipe".NYT Cooking.RetrievedFebruary 7,2023.

- ^Fernandez, Doreen G. (2019).Tikim: Essays on Philippine Food and Culture.BRILL. p. 33.ISBN9789004414792.

- ^"Tsampoy".Tagalog Lang.RetrievedNovember 1,2021.

- ^Dalziel, J.M. (1926). "African Leather Dyes".Bulletin of Miscellaneous Information.6(6). Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew: 231.doi:10.2307/4118651.JSTOR4118651.

- ^United States Department of the Army(2009).The Complete Guide to Edible Wild Plants.New York:Skyhorse Publishing.p. 101.ISBN978-1-60239-692-0.OCLC277203364.

- ^Richmond, Simon; Eimer, David; Karlin, Adam; Louis, Regis St; Ray, Nick (2017).Myanmar (Burma).Lonely Planet.ISBN978-1-78657-546-3.

- ^"ရာသီစာ အညာမန်ကျည်းရွက်သုပ်".MDN - Myanmar DigitalNews(in Burmese).RetrievedJuly 22,2022.

- ^Tamarind Seeds.agriculturalproductsindia.com

- ^PROSEA

- ^Havinga, Reinout M.; Hartl, Anna; Putscher, Johanna; Prehsler, Sarah; Buchmann, Christine; Vogl, Christian R. (February 2010). "Tamarindus IndicaL. (Fabaceae): Patterns of Use in Traditional African Medicine ".Journal of Ethnopharmacology.127(3): 573–588.doi:10.1016/j.jep.2009.11.028.PMID19963055.

- ^Panthong, A; Khonsung, P; Kunanusorn, P; Wongcome, T; Pongsamart, S (July 2008). "The laxative effect of fresh pulp aqueous extracts of Thai Tamarind cultivars".Planta Medica.74(9).doi:10.1055/s-0028-1084885.

- ^"Tamarind".The Wood Database.RetrievedDecember 22,2016.

- ^McGee, Joah (2015).The Golden Path.Pariyatti Publishing.ISBN9781681720135.

- ^Salma, U.; Miah, A. G.; Tareq, K. M. A.; Maki, T.; Tsujii, H. (April 1, 2007)."Effect of DietaryRhodobacter capsulatuson Egg-Yolk Cholesterol and Laying Hen Performance ".Poultry Science.86(4): 714–719.doi:10.1093/ps/86.4.714.PMID17369543.

as well as in egg-yolk (13 and 16%)

- ^Chowdhury, SR; Sarker, DK; Chowdhury, SD; Smith, TK; Roy, PK; Wahid, MA (2005)."Effects of dietary tamarind on cholesterol metabolism in laying hens".Poultry Science.84(1): 56–60.doi:10.1093/ps/84.1.56.PMID15685942.

- ^Wegenast, CA (2022). "Acute kidney injury in dogs following ingestion of cream of tartar and tamarinds and the connection to tartaric acid as the proposed toxic principle in grapes and raisins".J Vet Emerg Crit Care.32(6): 812–816.doi:10.1111/vec.13234.PMID35869755.S2CID250989489.

- ^Imam, S.; Azhar, I.; Hasan, M. M.; Ali, M. S.; Ahmed, S. W. (2007). "Two triterpenes lupanone and lupeol isolated and identified from Tamarindus indica linn".Pakistan Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences.20(2): 125–7.PMID17416567.

- ^Razali, N.; Mat Junit, S.; Ariffin, A.; Ramli, N. S.; Abdul Aziz, A. (2015)."Polyphenols from the extract and fraction ofT. indicaseeds protected HepG2 cells against oxidative stress ".BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine.15:438.doi:10.1186/s12906-015-0963-2.PMC4683930.PMID26683054.

- ^"Asam or Tamarind tree (Tamarindus indica) on the Shores of Singapore".www.wildsingapore.com.RetrievedApril 14,2018.

- ^"Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations".

- ^National Research Council (January 25, 2008)."Tamarind".Lost Crops of Africa: Volume III: Fruits.Vol. 3. National Academies Press.doi:10.17226/11879.ISBN978-0-309-10596-5.RetrievedJuly 17,2008.

- ^"Ring-Tailed Lemur".Wisconsin Primate Research Center.RetrievedNovember 14,2016.

- ^D'Cruz, Mark."Ma-Ke Bonsai Care Guide forTamarindus indica".Ma-Ke Bonsai. Archived fromthe originalon May 14, 2012.RetrievedAugust 19,2011.

External links

[edit] Media related toTamarindus indicaat Wikimedia Commons

Media related toTamarindus indicaat Wikimedia Commons- SEA Hand Book-2009: Published by The Solvent Extractors' Association of India

- Tamarindus indicain Brunken, U., Schmidt, M., Dressler, S., Janssen, T., Thiombiano, A. & Zizka, G. 2008. West African plants – A Photo Guide.

- .Encyclopædia Britannica(11th ed.). 1911.

- ..1914.