The Chronicles of Narnia

The Chronicles of Narniaboxed set | |

| |

| Author | C. S. Lewis |

|---|---|

| Illustrator | Pauline Baynes |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Genre | |

| Publisher |

|

| Published | 16 October 1950 – 4 September 1956 |

| Media type | |

| Website | www |

The Chronicles of Narniais a series of sevenportal fantasynovels by British authorC. S. Lewis.Illustrated byPauline Baynesand originally published between 1950 and 1956, the series is set in the fictional realm ofNarnia,a fantasy world of magic, mythical beasts and talking animals. It narrates the adventures of various children who play central roles in the unfolding history of the Narnian world. Except inThe Horse and His Boy,the protagonists are all children from the real world who are magically transported to Narnia, where they are sometimes called upon by the lionAslanto protect Narnia from evil. The books span the entire history of Narnia, from its creation inThe Magician's Nephewto its eventual destruction inThe Last Battle.

The Chronicles of Narniais considered a classic ofchildren's literatureand is Lewis's best-selling work, having sold 120 million copies in 47 languages.[1]The serieshas been adaptedfor radio, television, the stage, film and video games.

Background and conception[edit]

Although Lewis originally conceived what would becomeThe Chronicles of Narniain 1939[2](the picture of a Faun with parcels in a snowy wood has a history dating to 1914),[3]he did not finish writing the first bookThe Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobeuntil 1949.The Magician's Nephew,the penultimate book to be published, but the last to be written, was completed in 1954. Lewis did not write the books in the order in which they were originally published, nor were they published in their current chronological order of presentation.[4]The original illustrator, Pauline Baynes, created pen and ink drawings for theNarniabooks that are still used in the editions published today. Lewis was awarded the 1956Carnegie MedalforThe Last Battle,the final book in the saga. The series was first referred to asThe Chronicles of Narniaby fellow children's authorRoger Lancelyn Greenin March 1951, after he had read and discussed with Lewis his recently completed fourth bookThe Silver Chair,originally entitledNight under Narnia.[5]

Lewis described the origin ofThe Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobein an essay entitled "It All Began with a Picture":

TheLionall began with a picture of aFauncarrying an umbrella and parcels in a snowy wood. This picture had been in my mind since I was about sixteen. Then one day, when I was about forty, I said to myself: "Let's try to make a story about it."[3]

Shortly before the start of World War II,many children were evacuatedto the English countryside in anticipation of attacks on London and other major urban areas by Nazi Germany. As a result, on 2 September 1939, three school girls named Margaret, Mary and Katherine[6]came to live atThe KilnsinRisinghurst,Lewis's home three miles east ofOxfordcity centre. Lewis later suggested that the experience gave him a new appreciation of children and in late September[7]he began a children's story on an odd sheet of paper which has survived as part of another manuscript:

This book is about four children whose names were Ann, Martin, Rose and Peter. But it is most about Peter who was the youngest. They all had to go away from London suddenly because of Air Raids, and because Father, who was in the Army, had gone off to the War and Mother was doing some kind of war work. They were sent to stay with a kind of relation of Mother's who was a very old professor who lived all by himself in the country.[8]

In "It All Began with a Picture" C. S. Lewis continues:

At first, I had very little idea how the story would go. But then suddenly Aslan came bounding into it. I think I had been having a good many dreams of lions about that time. Apart from that, I don't know where the Lion came from or why he came. But once he was there, he pulled the whole story together, and soon he pulled the six other Narnian stories in after him.[3]

Although Lewis pleaded ignorance about the source of his inspiration for Aslan,Jared Lobdell,digging into Lewis's history to explore the making of the series, suggestsCharles Williams's 1931 novelThe Place of the Lionas a likely influence.[9]

The manuscript forThe Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobewas complete by the end of March 1949.

Name[edit]

The nameNarniais based onNarni,Italy, written inLatinasNarnia.Green wrote:

WhenWalter Hooperasked where he found the word 'Narnia', Lewis showed himMurray's Small Classical Atlas,ed.G.B. Grundy(1904), which he acquired when he was readingthe classicswithMr [William T.] KirkpatrickatGreat Bookham[1914–1917]. On plate 8 of the Atlas is a map of ancient Italy. Lewis had underscored the name of a little town called Narnia, simply because he liked the sound of it. Narnia – or 'Narni' in Italian – is inUmbria,halfway betweenRomeandAssisi.[10][11]

Publication history[edit]

The Chronicles of Narnia'sseven books have been in continuous publication since 1956, selling over 100 million copies in 47 languages and with editions inBraille.[12][13][14]

The first five books were originally published in the United Kingdom by Geoffrey Bles. The first edition ofThe Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobewas released in London on 16 October 1950. Although three more books,Prince Caspian,The Voyage of the Dawn TreaderandThe Horse and His Boy,were already complete, they were not released immediately at that time, but instead appeared (along withThe Silver Chair) one at a time in each of the subsequent years (1951–1954). The last two books (The Magician's NephewandThe Last Battle) were published in the United Kingdom originally byThe Bodley Headin 1955 and 1956.[15][16]

In the United States, the publication rights were first owned byMacmillan Publishers,and later byHarperCollins.The two issued both hardcover and paperback editions of the series during their tenure as publishers, while at the same timeScholastic, Inc.produced paperback versions for sale primarily through direct mail order, book clubs, and book fairs. HarperCollins also published several one-volume collected editions containing the full text of the series. As noted below (seeReading order), the first American publisher, Macmillan, numbered the books in publication sequence, whereas HarperCollins, at the suggestion of Lewis's stepson, opted to use the series' internal chronological order when they won the rights to it in 1994. Scholastic switched the numbering of its paperback editions in 1994 to mirror that of HarperCollins.[4]

Books[edit]

The seven books that make upThe Chronicles of Narniaare presented here in order of original publication date:

The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe(1950)[edit]

The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe,completed by the end of March 1949[17]and published by Geoffrey Bles in the United Kingdom on 16 October 1950, tells the story of four ordinary children:Peter,Susan,Edmund,andLucy Pevensie,Londoners who were evacuated to the English countrysidefollowing the outbreak ofWorld War II.They discover a wardrobe in ProfessorDigory Kirke's house that leads to the magical land of Narnia. The Pevensie children help Aslan, a talking lion, save Narnia from the evilWhite Witch,who has reigned for a century of perpetual winter with no Christmas. The children become kings and queens of this new-found land and establish the Golden Age of Narnia, leaving a legacy to be rediscovered in later books.

Prince Caspian: The Return to Narnia(1951)[edit]

Completed after Christmas 1949[18]and published on 15 October 1951,Prince Caspian: The Return to Narniatells the story of the Pevensie children's second trip to Narnia, a year (on Earth) after their first. They are drawn back by the power of Susan's horn, blown byPrince Caspianto summon help in his hour of need. Narnia as they knew it is no more, as 1,300 years have passed, their castle is in ruins, and all Narnians have retreated so far within themselves that only Aslan's magic can wake them. Caspian has fled into the woods to escape his uncle,Miraz,who has usurped the throne. The children set out once again to save Narnia.

The Voyage of the Dawn Treader(1952)[edit]

Written between January and February 1950[19]and published on 15 September 1952,The Voyage of the Dawn Treadersees Edmund and Lucy Pevensie, along with theirpriggishcousin,Eustace Scrubb,return to Narnia, three Narnian years (and one Earth year) after their last departure. Once there, they join Caspian's voyage on the shipDawn Treaderto find the seven lords who were banished when Miraz took over the throne. This perilous journey brings them face to face with many wonders and dangers as they sail toward Aslan's country at the edge of the world.

The Silver Chair(1953)[edit]

Completed at the beginning of March 1951[19]and published 7 September 1953,The Silver Chairis the first Narnia book not involving the Pevensie children, focusing instead on Eustace. Several months afterThe Voyage of the Dawn Treader,Aslan calls Eustace back to Narnia along with his classmateJill Pole.They are given four signs to aid them in the search for Prince Caspian's sonRilian,who disappeared ten years earlier on a quest to avenge his mother's death. Fifty years have passed in Narnia since the events fromThe Voyage of the Dawn Treader;Eustace is still a child, but Caspian, barely an adult in the previous book, is now an old man. Eustace and Jill, with the help ofPuddleglumthe Marsh-wiggle, face danger and betrayal on their quest to find Rilian.

The Horse and His Boy(1954)[edit]

Begun in March and completed at the end of July 1950,[19]The Horse and His Boywas published on 6 September 1954. The story takes place during the reign of the Pevensies in Narnia, an era which begins and ends in the last chapter ofThe Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe.The protagonists, a young boy namedShastaand a talking horse namedBree,both begin in bondage in the country ofCalormen.By "chance", they meet and plan their return to Narnia and freedom. Along the way they meetAravisand her talking horseHwin,who are also fleeing to Narnia.

The Magician's Nephew(1955)[edit]

Completed in February 1954[20] and published by Bodley Head in London on 2 May 1955,The Magician's Nephewserves as a prequel and presents Narnia'sorigin story:how Aslan created the world and how evil first entered it.Digory Kirkeand his friendPolly Plummerstumble into different worlds by experimenting with magic rings given to them by Digory's uncle. In the dying world ofCharnthey awaken Queen Jadis, and another world turns out to be the beginnings of the Narnian world (where Jadis later becomes theWhite Witch). The story is set in 1900, when Digory was a 12-year-old boy. He is a middle-aged professor by the time he hosts the Pevensie children inThe Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe40 years later.

The Last Battle(1956)[edit]

Completed in March 1953[21]and published 4 September 1956,The Last Battlechronicles the end of the world of Narnia. Approximately two hundred Narnia years after the events ofThe Silver Chair,Jill and Eustace return to save Narnia from the apeShift,who tricksPuzzlethe donkey into impersonating the lion Aslan, thereby precipitating a showdown between the Calormenes andKing Tirian.This leads to the end of Narnia as it is known throughout the series, but allows Aslan to lead the characters to the "true" Narnia.

Reading order[edit]

Fans of the series often have strong opinions over the order in which the books should be read. The issue revolves around the placement ofThe Magician's NephewandThe Horse and His Boyin the series. Both are set significantly earlier in the story of Narnia than their publication order and fall somewhat outside the mainstory arcconnecting the others. The reading order of the other five books is not disputed.

| Book | Published | Internal chronology[22] | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Earth | Narnia | ||

| The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe | 1950 | 1940 | 1000–1015 |

| Prince Caspian | 1951 | 1941 | 2303 |

| The Voyage of the Dawn Treader | 1952 | Summer 1942 | 2306–2307 |

| The Silver Chair | 1953 | Autumn 1942 | 2356 |

| The Horse and His Boy | 1954 | [1940] | 1014 |

| The Magician's Nephew | 1955 | 1900 | 1 |

| The Last Battle | 1956 | 1949 | 2555 |

When first published, the books were not numbered. The first American publisher, Macmillan, enumerated them according to their original publication order, while some early British editions specified the internal chronological order. When HarperCollins took over the series rights in 1994, they adopted the internal chronological order.[4]To make the case for the internal chronological order, Lewis's stepson,Douglas Gresham,quoted Lewis's 1957 reply to a letter from an American fan who was having an argument with his mother about the order:

- I think I agree with your [chronological] order for reading the books more than with your mother's. The series was not planned beforehand as she thinks. When I wroteThe LionI did not know I was going to write any more. Then I wroteP. Caspianas a sequel and still didn't think there would be any more, and when I had doneThe VoyageI felt quite sure it would be the last, but I found I was wrong. So perhaps it does not matter very much in which order anyone read them. I'm not even sure that all the others were written in the same order in which they were published.[23]

In the 2005 HarperCollins adult editions of the books, the publisher cites this letter to assert Lewis's preference for the numbering they adopted by including this notice on the copyright page:

- AlthoughThe Magician's Nephewwas written several years after C. S. Lewis first began The Chronicles of Narnia, he wanted it to be read as the first book in the series. HarperCollins is happy to present these books in the order in which Professor Lewis preferred.

Paul Ford cites several scholars who have weighed in against this view,[24]and continues, "most scholars disagree with this decision and find it the least faithful to Lewis's deepest intentions".[4]Scholars and readers who appreciate the original order believe that Lewis was simply being gracious to his youthful correspondent and that he could have changed the books' order in his lifetime had he so desired.[25]They maintain that much of the magic of Narnia comes from the way the world is gradually presented inThe Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe– that the mysterious wardrobe, as a narrative device, is a much better introduction to Narnia thanThe Magician's Nephew,where the word "Narnia" appears in the first paragraph as something already familiar to the reader. Moreover, they say, it is clear from the texts themselves thatThe Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobewas intended to be read first. When Aslan is first mentioned inThe Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe,for example, the narrator says that "None of the children knew who Aslan was, any more than you do" — which is nonsensical if one has already readThe Magician's Nephew.[26]Other similar textual examples are also cited.[27]

Doris Meyer, author ofC. S. Lewis in ContextandBareface: A guide to C. S. Lewis,writes that rearranging the stories chronologically "lessens the impact of the individual stories" and "obscures the literary structures as a whole".[28]Peter Schakel devotes an entire chapter to this topic in his bookImagination and the Arts in C. S. Lewis: Journeying to Narnia and Other Worlds,and inReading with the Heart: The Way into Narniahe writes:

- The only reason to readThe Magician's Nephewfirst [...] is for the chronological order of events, and that, as every story teller knows, is quite unimportant as a reason. Often the early events in a sequence have a greater impact or effect as a flashback, told after later events which provide background and establish perspective. So it is [...] with theChronicles.The artistry, the archetypes, and the pattern of Christian thought all make it preferable to read the books in the order of their publication.[26]

Main characters[edit]

Aslan[edit]

Aslan, the Great Lion, is thetitularlion ofThe Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe,and his role in Narnia is developed throughout the remaining books. He is also the only character to appear in all seven books. Aslan is a talking lion, the King of Beasts, son of theEmperor-Over-the-Sea.He is a wise, compassionate, magical authority (both temporal and spiritual) who serves as mysterious and benevolent guide to the human children who visit, as well as being the guardian and saviour of Narnia. C. S. Lewis described Aslan as an alternative version ofJesusas the form in which he may have appeared in an alternative reality.[29][30]In his bookMiracles,C.S. Lewis argues that the possible existence of other worlds with other sentient life-forms should not deter or detract from beingChristian:

[The universe] may be full of lives that have been redeemed in modes suitable to their condition, of which we can form no conception. It may be full of lives that have been redeemed in the very same mode as our own. It may be full of things quite other than life in which God is interested though we are not.[31]

Pevensie family[edit]

The four Pevensie siblings are the main human protagonists ofThe Chronicles of Narnia.Varying combinations of some or all of them appear in five of the seven novels. They are introduced inThe Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe(although their surname is not revealed untilThe Voyage of the Dawn Treader), and eventually become Kings and Queens of Narnia reigning as a tetrarchy. Although introduced in the series as children, the siblings grow up into adults while reigning in Narnia. They go back to being children once they get back to their own world, but feature as adults inThe Horse and His Boyduring their Narnian reign.

All four appear inThe Lion, the Witch, and the WardrobeandPrince Caspian;in the latter, however, Aslan tells Peter and Susan that they will not return, as they are getting too old. Susan, Lucy, and Edmund appear inThe Horse and His Boy—Peter is said to be away fighting giants on the other side of Narnia. Lucy and Edmund appear inThe Voyage of the Dawn Treader,where Aslan tells them, too, that they are getting too old. Peter, Edmund, and Lucy appear as Kings and Queens in Aslan's Country inThe Last Battle;Susan does not. Asked by a child in 1958 if he would please write another book entitled "Susan of Narnia" so that the entire Pevensie family would be reunited, C. S. Lewis replied: "I am so glad you like the Narnian books and it was nice of you to write and tell me. There's no use just askingmeto write more. When stories come into my mind I have to write them, and when they don't I can't!… "[32][citation not found]

Lucy Pevensie[edit]

Lucy is the youngest of the four Pevensie siblings. Of all the Pevensie children, Lucy is the closest to Aslan, and of all the human characters who visit Narnia, Lucy is perhaps the one who believes in Narnia the most. InThe Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe,she initiates the story by entering Narnia through the wardrobe, and (with Susan) witnesses Aslan's execution and resurrection. She is named Queen Lucy the Valiant. InPrince Caspian,she is the first to see Aslan when he comes to guide them. InThe Voyage of the Dawn Treader,it is Lucy who breaks the spell of invisibility on theDufflepuds.As an adult inThe Horse and His Boy,she helps fight the Calormenes at Anvard. Although a minor character inThe Last Battle,much of the closing chapter is seen from her point of view.

Edmund Pevensie[edit]

Edmund is the second child to enter Narnia inThe Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe,where he falls under the White Witch's spell from eating theTurkish delightshe gives him. Instantiating the book's Christian theme of betrayal, repentance, and subsequent redemption via blood sacrifice, he betrays his siblings to the White Witch, but quickly realizes her true nature and her evil intentions, and is redeemed by the sacrifice of Aslan's life. He is named King Edmund the Just. InPrince CaspianandThe Voyage of the Dawn Treader,he supports Lucy; inThe Horse and His Boy,he leads the Narnian delegation to Calormen and, later, the Narnian army breaking the siege at Anvard.

Susan Pevensie[edit]

InThe Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe,Susan accompanies Lucy to see Aslan die and rise again. She is named Queen Susan the Gentle. InPrince Caspian,however, she is the last of the four to believe and follow Lucy when the latter is called by Aslan to guide them. As an adult queen inThe Horse and His Boy,she is courted by Prince Rabadash of Calormen, but refuses his marriage proposal, and his angry response leads the story to its climax. InThe Last Battle,she has stopped believing in Narnia and remembers it only as a childhood game, though Lewis mentioned in a letter to a fan that he thought she may eventually believe again: "The books don't tell us what happened to Susan…But there is plenty of time for her to mend, and perhaps she will get to Aslan's country in the end—in her own way. "[33]

Peter Pevensie[edit]

Peter is the eldest of the Pevensies. InThe Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe,he kills Maugrim, a talking wolf, to save Susan, and leads the Narnian army against the White Witch. Aslan names himHigh King,and he is known as Peter the Magnificent. InPrince Caspian,he duels the usurper KingMirazto restore Caspian's throne. InThe Last Battle,it is Peter whom Aslan entrusts with the duty of closing the door on Narnia for the final time.

Eustace Scrubb[edit]

Eustace Clarence Scrubb is a cousin of the Pevensies, and a classmate of Jill Pole at their school Experiment House. He is portrayed at first as a brat and a bully, but comes to improve his nasty behaviour when his greed turns him into a dragon for a while. His distress at having to live as a dragon causes him to reflect upon how horrible he has been, and his subsequent improved character is rewarded when Aslan changes him back into a boy. In the later books, Eustace comes across as a much nicer person, although he is still rather grumpy and argumentative. Nonetheless, he becomes a hero along with Jill Pole when the pair succeed in freeing the lost Prince Rilian from the clutches of an evil witch. He appears inThe Voyage of the Dawn Treader,The Silver Chair,andThe Last Battle.

Jill Pole[edit]

Jill Pole is a schoolmate of Eustace Scrubb. She appears inThe Silver Chair,where she is the viewpoint character for most of the action, and returns inThe Last Battle.InThe Silver Chair,Eustace introduces her to the Narnian world, where Aslan gives her the task of memorising a series of signs that will help her and Eustace on their quest to find Caspian's lost son. InThe Last Battle,she and Eustace accompany King Tirian in his ill-fated defence of Narnia against the Calormenes.

Professor Digory Kirke[edit]

Digory Kirke is the nephew referred to in the title ofThe Magician's Nephew.He first appears as a minor character inThe Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe,known only as "The Professor", who hosts the Pevensie children when they are evacuated from London and defends Lucy's story of having found a country in the back of the wardrobe. InThe Magician's Nephew,the young Digory, thanks to his uncle's magical experimentation, inadvertently bringsJadisfrom her dying homeworld of Charn to the newly created world of Narnia; to rectify his mistake, Aslan sends him to fetch a magical apple which will protect Narnia and heal his dying mother. He returns inThe Last Battle.

Polly Plummer[edit]

Polly Plummer appears inThe Magician's NephewandThe Last Battle.She is the next-door neighbour of the young Digory Kirke. She is tricked by a wicked magician (who is Digory's uncle) into touching a magic ring which transports her to theWood between the Worldsand leaves her there stranded. The wicked uncle persuades Digory to follow her with a second magic ring that has the power to bring her back. This sets up the pair's adventures into other worlds, and they witness the creation of Narnia as described inThe Magician's Nephew.She appears at the end ofThe Last Battle.

Tumnus[edit]

Tumnus theFaun,called "Mr Tumnus" by Lucy, is featured prominently inThe Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobeand also appears inThe Horse and His BoyandThe Last Battle.He is the first creature Lucy meets in Narnia, as well as the first Narnian to be introduced in the series; he invites her to his home with the intention of betraying her to Jadis, but quickly repents and befriends her. InThe Horse and His Boy,he devises the Narnian delegation's plan of escape from Calormen. He returns for a brief dialogue at the end ofThe Last Battle.Lewis's initial inspiration for the entire series was a mental image of a faun in a snowy wood; Tumnus is that faun.[3]

Caspian[edit]

Caspian is first introduced in the book titled after him, as the young nephew and heir of King Miraz. Fleeing potential assassination by his uncle, he becomes leader of the Old Narnian rebellion against theTelmarineoccupation. With the help of the Pevensies, he defeats Miraz's army and becomes King Caspian X of Narnia. InThe Voyage of the Dawn Treader,he leads an expedition out into the eastern ocean to findSeven Lords,whom Miraz had exiled, and ultimately to reach Aslan's Country. InThe Silver Chair,he makes two brief appearances as an old, dying man, but at the end is resurrected in Aslan's Country.

Trumpkin[edit]

Trumpkin the Dwarf is the narrator of several chapters ofPrince Caspian;he is one of Caspian's rescuers and a leading figure in the "Old Narnian" rebellion, and accompanies the Pevensie children from the ruins of Cair Paravel to the Old Narnian camp. InThe Voyage of the Dawn Treader,we learn that Caspian has made him his Regent in Narnia while he is away at sea, and he appears briefly in this role (now elderly and very deaf) inThe Silver Chair.

Reepicheep[edit]

Reepicheep the Mouse is the leader of the Talking Mice of Narnia inPrince Caspian.Utterly fearless, infallibly courteous, and obsessed with honour, he is badly wounded in the final battle but healed by Lucy and Aslan. InThe Voyage of the Dawn Treader,his role is greatly expanded; he becomes a visionary as well as a warrior, and ultimately his willing self-exile to Aslan's Country breaks the enchantment on the last three of the Lost Lords, thus achieving the final goal of the quest. Lewis identified Reepicheep as "specially" exemplifying the latter book's theme of "the spiritual life".[34]Reepicheep makes one final cameo appearance at the end ofThe Last Battle,in Aslan's Country.

Puddleglum[edit]

Puddleglum the Marsh-wiggle guides Eustace and Jill on their quest inThe Silver Chair.Though always comically pessimistic, he provides the voice of reason and as such intervenes critically in the climactic enchantment scene.

Shasta / Cor[edit]

Shasta, later known as Cor ofArchenland,is the principal character inThe Horse and His Boy.Born the eldest son and heir ofKing Luneof Archenland, and elder twin of Prince Corin, Cor was kidnapped as an infant and raised as a fisherman's son inCalormen.With the help of the talking horse Bree, Shasta escapes from being sold into slavery and makes his way northward to Narnia. On the journey his companion Aravis learns of an imminent Calormene surprise attack on Archenland; Shasta warns the Archenlanders in time and discovers his true identity and original name. At the end of the story he marries Aravis and becomes King of Archenland.

Aravis[edit]

Aravis, daughter of Kidrash Tarkaan, is a character inThe Horse and His Boy.Escaping a forced betrothal to the loathsome Ahoshta, she joins Shasta on his journey and inadvertently overhears a plot by Rabadash, crown prince of Calormen, to invade Archenland. She later marries Shasta, now known as Prince Cor, and becomes queen of Archenland at his side.

Bree[edit]

Bree (Breehy-hinny-brinny-hoohy-hah) is Shasta's mount and mentor inThe Horse and His Boy.A Talking Horse of Narnia, he wandered into Calormen as a foal and was captured. He first appears as a Calormene nobleman's war-horse; when the nobleman buys Shasta as a slave, Bree organises and carries out their joint escape. Though friendly, he is also vain and a braggart until his encounter with Aslan late in the story.

Tirian[edit]

The last King of Narnia is the viewpoint character for much ofThe Last Battle.Having rashly killed a Calormene for mistreating a Narnian Talking Horse, he is imprisoned by the villainous ape Shift but released by Eustace and Jill. Together they fight faithfully to the last and are welcomed into Aslan's Kingdom.

Antagonists[edit]

Jadis, the White Witch[edit]

Jadis, commonly known during her rule of Narnia as the White Witch, is the mainvillainofThe Lion, The Witch and the WardrobeandThe Magician's Nephew—the onlyantagonistto appear in more than one Narnia book. InThe Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe,she is the witch responsible for the freezing of Narnia resulting in the Hundred Year Winter; she turns her enemies into statues and kills Aslan on the Stone Table, but is killed by him in battle after his resurrection. InThe Magician's Nephew,she is wakened from a magical sleep by Digory in the dead world of Charn and inadvertently brought toVictorianLondonbefore being transported to Narnia, where she steals an apple to grant her the gift of immortality.

Miraz[edit]

King Miraz is the lead villain ofPrince Caspian.Prior to the book's opening he has killed King Caspian IX, father of the titular Prince Caspian, and usurped his throne as king of the Telmarine colonizers in Narnia. He raises Caspian as his heir, but seeks to kill him after his own son is born. As the story progresses he leads the Telmarine war against the Old Narnian rebellion; he is defeated in single combat by Peter and then murdered by one of his own lords.

Lady of the Green Kirtle[edit]

The Lady of the Green Kirtle is the lead villain ofThe Silver Chair,and is also referred to in that book as "the Queen of Underland" or simply as "the Witch". She rules an underground kingdom through magical mind-control. Prior to the events ofThe Silver Chair,she has murdered Caspian's Queen and then seduced and abducted his son Prince Rilian. She encounters the protagonists on their quest and sends them astray. Confronted by them later, she attempts to enslave them magically; when that fails, she attacks them in the form of a serpent and is killed.

Rabadash[edit]

Prince Rabadash, heir to the throne ofCalormen,is the primary antagonist ofThe Horse and His Boy.Hot-headed, arrogant, and entitled, he brings Queen Susan of Narnia—along with a small retinue of Narnians, including King Edmund—to Calormen in the hope that Susan will marry him. When the Narnians realize that Rabadash may force Susan to accept his marriage proposal, they spirit Susan out of Calormen by ship. Incensed, Rabadash launches a surprise attack onArchenlandwith the ultimate intention of raiding Narnia and taking Susan captive. His plan is foiled when Shasta and Aravis warn the Archenlanders of his impending strike. After being captured by Edmund, Rabadash blasphemes against Aslan. Aslan then temporarily transforms him into a donkey as punishment.

Shift the Ape[edit]

Shift is the most prominent villain ofThe Last Battle.He is an elderlyTalkingApe—Lewis does not specify what kind of ape, but Pauline Baynes' illustrations depict him as achimpanzee.He persuades the naïve donkey Puzzle to pretend to be Aslan (wearing a lion-skin) in order to seize control of Narnia, and proceeds to cut down the forests, enslave the other Talking Beasts, and invite the Calormenes to invade. He loses control of the situation due to over-indulging inalcohol,and is eventually swallowed up by the evil Calormene godTash.

Title characters[edit]

- The Magician's Nephew–Digory Kirke(Andrew Ketterleyis the magician)

- The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe–Aslan,Jadis

- The Horse and His Boy–Bree,Shasta

- Prince Caspian–Prince Caspian

Appearances of main characters[edit]

| Character | Book | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe (1950) | Prince Caspian: The Return to Narnia (1951) | The Voyage of the Dawn Treader (1952) | The Silver Chair (1953) | The Horse and His Boy (1954) | The Magician's Nephew (1955) | The Last Battle (1956) | Total

Appearances | |

| Aslan | Major | 7 | ||||||

| Peter Pevensie | Major | Minor | 3 | |||||

| Susan Pevensie | Major | Minor | 3 | |||||

| Edmund Pevensie | Major | Minor | Minor | 5 | ||||

| Lucy Pevensie | Major | Minor | Minor | 5 | ||||

| Eustace Scrubb | Major | Major | 3 | |||||

| Jill Pole | Major | Major | 2 | |||||

| (Professor) Digory Kirke | Minor | Major | Minor | 3 | ||||

| Polly Plummer | Major | Minor | 2 | |||||

| (Mr) Tumnus | Major | Minor | Minor | 3 | ||||

| Prince/King Caspian | Major | Minor | Cameo | 4 | ||||

| Trumpkin the Dwarf | Major | Minor | Cameo | 3 | ||||

| Reepicheep the Mouse | Minor | Major | Minor | 3 | ||||

| Puddleglum | Major | Cameo | 2 | |||||

| Shasta (Prince Cor) | Major | Cameo | 2 | |||||

| Aravis Tarkheena | Major | Cameo | 2 | |||||

| Bree | Major | Cameo | 2 | |||||

| King Tirian | Major | 1 | ||||||

| Jadis (The White Witch) | Major | Major | 2 | |||||

| King Miraz | Major | 1 | ||||||

| The Lady of the Green Kirtle | Major | 1 | ||||||

| Prince Rabadash | Major | 1 | ||||||

| Shift the Ape | Major | 1 | ||||||

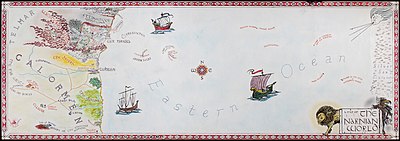

Narnian geography[edit]

The Chronicles of Narniadescribes the world in which Narnia exists as one major landmass encircled by an ocean.[35]Narnia's capital sits on the eastern edge of the landmass on the shores of the Great Eastern Ocean. This ocean contains the islands explored inThe Voyage of the Dawn Treader.On the main landmass Lewis places the countries of Narnia, Archenland, Calormen, andTelmar,along with a variety of other areas that are not described as countries. The author also provides glimpses of more fantastic locations that exist in and around the main world of Narnia, including an edge and an underworld.[36]

Influences[edit]

Lewis's life[edit]

Lewis's early life has parallels withThe Chronicles of Narnia.At the age of seven, he moved with his family to a large house on the edge ofBelfast.Its long hallways and empty rooms inspired Lewis and his brother to invent make-believe worlds whilst exploring their home, an activity reflected in Lucy's discovery of Narnia inThe Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe.[37]Like Caspian and Rilian, Lewis lost his mother at an early age, spending much of his youth in English boarding schools similar to those attended by the Pevensie children, Eustace Scrubb, and Jill Pole. During World War II many children were evacuated from London and other urban areas because of German air raids. Some of these children, including one named Lucy (Lewis's goddaughter) stayed with him at his home The Kilns near Oxford, just as the Pevensies stayed withThe ProfessorinThe Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe.[38]

Influences from mythology and cosmology[edit]

Drew Trotter, president of the Center for Christian Study, noted that the producers of the filmThe Chronicles of Narnia: The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobefelt that the books' plots adhere to the archetypal "monomyth"pattern as detailed inJoseph Campbell'sThe Hero with a Thousand Faces.[39]

Lewis was widely read inmedieval Celtic literature,an influence reflected throughout the books, and most strongly inThe Voyage of the Dawn Treader.The entire book imitates one of theimmrama,a type of traditionalOld Irishtale that combines elements of Christianity andIrish mythologyto tell the story of a hero's sea journey to theOtherworld.[40][41]

Planet Narnia[edit]

Michael Ward's 2008 bookPlanet Narnia[42]proposes that each of the seven books related to one of theseven moving heavenly bodies or "planets"known in the Middle Ages according to thePtolemaic geocentric modelofcosmology(a theme to which Lewis returned habitually throughout his work). At that time, each of these heavenly bodies was believed to have certain attributes, and Ward contends that these attributes were deliberately but subtly used by Lewis to furnish elements of the stories of each book:

- InThe Lion[the child protagonists] become monarchs under sovereignJove;inPrince Caspianthey harden under strongMars;inThe "Dawn Treader"they drink light under searchingSol;inThe Silver Chairthey learn obedience under subordinateLuna;inThe Horse and His Boythey come to love poetry under eloquentMercury;inThe Magician's Nephewthey gain life-giving fruit under fertileVenus;and inThe Last Battlethey suffer and die under chillingSaturn.[43]

Lewis's interest in the literary symbolism of medieval and Renaissance astrology is more overtly referenced in other works such as his study of medieval cosmologyThe Discarded Image,and in his early poetry as well as inSpace Trilogy.Narnia scholar Paul F. Ford finds Ward's assertion that Lewis intendedThe Chroniclesto be an embodiment of medieval astrology implausible,[44]though Ford addresses an earlier (2003) version of Ward's thesis (also calledPlanet Narnia,published in theTimes Literary Supplement). Ford argues that Lewis did not start with a coherent plan for the books, but Ward's book answers this by arguing that the astrological associations grew in the writing:

- Jupiter was... [Lewis's] favourite planet, part of the "habitual furniture" of his mind...The Lionwas thus the first example of that "idea that he wanted to try out".Prince CaspianandThe "Dawn Treader"naturally followed because Mars and Sol were both already connected in his mind with the merits of theAlexandertechnique.... at some point after commencingThe Horse and His Boyhe resolved to treat all seven planets, for seven such treatments of his idea would mean that he had "worked it out to the full".[45]

A quantitative analysis on the imagery in the different books ofThe Chroniclesgives mixed support to Ward's thesis:The Voyage of the Dawn Treader,The Silver Chair,The Horse and His Boy,andThe Magician's Nephewdo indeed employ concepts associated with, respectively, Sol, Luna, Mercury, and Venus, far more often than chance would predict, butThe Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe,Prince Caspian,andThe Last Battlefall short of statistical correlation with their proposed planets.[46]

Influences from literature[edit]

George MacDonald'sPhantastes(1858) influenced the structure and setting of "The Chronicles".[clarification needed]It was a work that was "a great balm to the soul".[47]

Platowas an undeniable influence on Lewis's writing ofThe Chronicles.Most clearly, Digory explicitly invokes Plato's name at the end ofThe Last Battle,to explain how the old version of Narnia is but a shadow of the newly revealed "true" Narnia. Plato's influence is also apparent inThe Silver Chairwhen the Queen of the Underland attempts to convince the protagonists that the surface world is not real. She echoes the logic ofPlato's Caveby comparing the sun to a nearby lamp, arguing that reality is only that which is perceived in the immediate physical vicinity.[48]

The White Witch inThe Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobeshares many features, both of appearance and character, with the villainous Duessa ofEdmund Spenser'sFaerie Queene,a work Lewis studied in detail. Like Duessa, she falsely styles herself Queen; she leads astray the erring Edmund with false temptations; she turns people into stone as Duessa turns them into trees. Both villains wear opulent robes and deck their conveyances out with bells.[49]InThe Magician's NephewJadis takes on echoes ofSatanfromJohn Milton'sParadise Lost:she climbs over the wall of the paradisal garden in contempt of the command to enter only by the gate, and proceeds to tempt Digory as Satan temptedEve,with lies and half-truths.[50]Similarly, the Lady of the Green Kirtle inThe Silver Chairrecalls both the snake-woman Errour inThe Faerie Queeneand Satan's transformation into a snake inParadise Lost.[51]

Lewis readEdith Nesbit's children's books as a child and was greatly fond of them.[52]He describedThe Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobearound the time of its completion as "a children's book in the tradition of E. Nesbit".[53]The Magician's Nephewin particular bears strong resemblances to Nesbit'sThe Story of the Amulet(1906). This novel focuses on four children living in London who discover a magic amulet. Their father is away and their mother is ill, as is the case with Digory. They manage to transport the queen ofancient Babylonto London and she is the cause of a riot; likewise, Polly and Digory transport Queen Jadis to London, sparking a very similar incident.[52]

Marsha Daigle-Williamson argues thatDante'sDivine Comedyhad a significant impact on Lewis's writings. In the Narnia series, she identifies this influence as most apparent inThe Voyage of the Dawn TreaderandThe Silver Chair.[54]Daigle-Williamson identifies the plot ofThe Voyage of the Dawn Treaderas a Dantean journey with a parallel structure and similar themes.[55]She likewise draws numerous connections betweenThe Silver Chairand the events of Dante'sInferno.[56]

Colin Duriez,writing on the shared elements found in both Lewis's andJ. R. R. Tolkien's works, highlights the thematic similarities between Tolkien's poemImramand Lewis'sThe Voyage of the Dawn Treader.[57]

Influences on other works[edit]

The Chronicles of Narniais considered a classic ofchildren's literature.[58][59]

Influences on literature[edit]

The Chronicles of Narniahas been a significant influence on both adult and children's fantasy literature in the post-World War II era. In 1976, the scholar Susan Cornell Poskanzer praised Lewis for his "strangely powerful fantasies". Poskanzer argued that children could relate toNarniabooks because the heroes and heroines were realistic characters, each with their own distinctive voice and personality. Furthermore, the protagonists become powerful kings and queens who decide the fate of kingdoms, while the adults in theNarniabooks tended to be buffoons, which by inverting the normal order of things was pleasing to many youngsters. However, Poskanzer criticized Lewis for what she regarded as scenes of gratuitous violence, which she felt were upsetting to children. Poskanzer also noted Lewis presented his Christian message subtly enough as to avoid boring children with overt sermonizing.[60]

Examples include:

Philip Pullman's fantasy series,His Dark Materials,is seen as a response toThe Chronicles.Pullman is a self-describedatheistwho wholly rejects the spiritual themes that permeateThe Chronicles,yet his series nonetheless addresses many of the same issues and introduces some similar character types, including talking animals. In another parallel, the first books in each series – Pullman'sNorthern LightsandThe Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe– both open with a young girl hiding in a wardrobe.[61][62][63]

Bill Willingham's comic book seriesFablesmakes reference at least twice to a king called "The Great Lion", a thinly veiled reference to Aslan. The series avoids explicitly referring to any characters or works that are not in the public domain.[citation needed]

The novelBridge to TerabithiabyKatherine Patersonhas Leslie, one of the main characters, reveal to Jesse her love of Lewis's books, subsequently lending himThe Chronicles of Narniaso that he can learn how to behave like a king. Her book also features the island name "Terabithia", which sounds similar toTerebinthia,a Narnian island that appears inPrince CaspianandThe Voyage of the Dawn Treader.Katherine Paterson herself acknowledges that Terabithia is likely to be derived from Terebinthia:

I thought I had made it up. Then, rereadingThe Voyage of the Dawn Treaderby C. S. Lewis, I realized that I had probably gotten it from the island of Terebinthia in that book. However, Lewis probably got that name from theterebinthtree in the Bible, so both of us pinched from somewhere else, probably unconsciously. "[64]

Science-fiction authorGreg Egan's short story "Oracle" depicts a parallel universe in which an author nicknamed Jack (Lewis's nickname) has written novels about the fictional "Kingdom of Nesica", and whose wife is dying of cancer, paralleling the death of Lewis's wifeJoy Davidman.Several Narnian allegories are also used to explore issues of religion and faith versus science and knowledge.[65]

Lev Grossman'sNew York Timesbest-sellerThe Magiciansis a contemporary dark fantasy about an unusually gifted young man obsessed with Fillory, the magical land of his favourite childhood books. Fillory is a thinly veiled substitute for Narnia, and clearly the author expects it to be experienced as such. Not only is the land home to many similar talking animals and mythical creatures, it is also accessed through a grandfather clock in the home of an uncle to whom five English children are sent during World War II. Moreover, the land is ruled by two Aslan-like rams named Ember and Umber, and terrorised by The Watcherwoman. She, like the White Witch, freezes the land in time. The book's plot revolves heavily around a place very like the "wood between the worlds" fromThe Magician's Nephew,an interworld waystation in which pools of water lead to other lands. This reference toThe Magician's Nephewis echoed in the title of the book.[66]

J. K. Rowling,author of theHarry Potterseries, has said that she was a fan of the works of Lewis as a child, and cites the influence ofThe Chronicleson her work: "I found myself thinking about the wardrobe route to Narnia when Harry is told he has to hurl himself at a barrier inKing's Cross Station– it dissolves and he's on platform Nine and Three-Quarters, and there's the train forHogwarts."[67]Nevertheless, she is at pains to stress the differences between Narnia and her world: "Narnia is literally a different world", she says, "whereas in the Harry books you go into a world within a world that you can see if you happen to belong. A lot of the humour comes from collisions between the magic and the everyday worlds. Generally there isn't much humour in the Narnia books, although I adored them when I was a child. I got so caught up I didn't think CS Lewis was especially preachy. Reading them now I find that his subliminal message isn't very subliminal."[67]New York Timeswriter Charles McGrath notes the similarity betweenDudley Dursley,the obnoxious son of Harry's neglectful guardians, and Eustace Scrubb, the spoiled brat who torments the main characters until he is redeemed by Aslan.[68]

The comic book seriesPakkins' LandbyGaryandRhoda Shipmanin which a young child finds himself in a magical world filled with talking animals, including a lion character named King Aryah, has been compared favorably to theNarniaseries. The Shipmans have cited the influence of C.S. Lewis and theNarniaseries in response to reader letters.[69] In 2019,Francis SpuffordwroteThe Stone Table,an unofficial Narniacontinuation novel.[70]

Influences on popular culture[edit]

As with any popular long-lived work, contemporary culture abounds with references to the lion Aslan, travelling via wardrobe and direct mentions ofThe Chronicles.Examples include:

Charlotte Staples Lewis,a character first seen early in the fourth season of the TV seriesLost,is named in reference to C. S. Lewis.LostproducerDamon Lindelofsaid that this was a clue to the direction the show would take during the season.[71]The bookUltimate Lost and Philosophy,edited by William Irwin and Sharon Kaye, contains a comprehensive essay onLostplot motifs based onThe Chronicles.[72]

The secondSNL Digital Shortby Andy Samberg and Chris Parnell features a humorousnerdcore hip hopsong titledChronicles of Narnia (Lazy Sunday),which focuses on the performers' plan to seeThe Chronicles of Narnia: The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobeat a cinema. It was described bySlatemagazine as one of the most culturally significantSaturday Night Liveskits in many years, and an important commentary on the state of rap.[73]Swedish Christian power metal bandNarnia,whose songs are mainly about theChronicles of Narniaor the Bible, feature Aslan on all their album covers.[74]The song "Further Up, Further In" from the albumRoom to Roamby Scottish-Irishfolk-rockbandThe Waterboysis heavily influenced byThe Chronicles of Narnia.The title is taken from a passage inThe Last Battle,and one verse of the song describes sailing to the end of the world to meet a king, similar to the ending ofVoyage of the Dawn Treader.C. S. Lewis is explicitly acknowledged as an influence in the liner notes of the 1990compact disc.

During interviews, the primary creator of the Japanese anime and gaming seriesDigimonhas said that he was inspired and influenced byThe Chronicles of Narnia.[75]

Its influence extends even tofan fiction:under thepen nameEdonohana, Rachel Manija Brown wrote "No Reservations: Narnia", which imaginedAnthony Bourdainexploring Narnia and its cuisine in the style of hisNo ReservationsTV show and book. Bourdain himself praised the fic's writing and "frankly a bit frightening" attention to detail.[76]

Christian themes[edit]

Lewis had authored a number of works on Christianapologeticsand other literature with Christian-based themes before writing theNarniabooks. The characterAslanis widely accepted by literary academia as being based on Jesus Christ.[77]Lewis did not initially plan to incorporateChristian theological conceptsinto hisNarniastories. Lewis maintained that theNarniabooks were not allegorical, preferring to term their Christian aspects a "supposition".[78][79]

The Chronicleshave, consequently, a large Christian following, and are widely used to promote Christian ideas. However, some Christians object thatThe Chroniclespromote "soft-sell paganism and occultism" due to recurring pagan imagery and themes.[80][81][82][83][84][85]

Criticism[edit]

Consistency[edit]

Gertrude Ward noted that "When Lewis wroteThe Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe,he clearly meant to create a world where there were no human beings at all. As the titles of Mr. Tumnus' books testify, in this world human beings are creatures of myth, while its common daily reality includes fauns and other creatures which are myth in our world. This worked well for the first volume of the series, but for later volumes Lewis thought up plots which required having more human beings in this world. InPrince Caspianhe still kept the original structure and explained that more humans had arrived from our world at a later time, overrunning Narnia. However, later on he gave in and changed the entire concept of this world – there have always been very many humans in this world, and Narnia is just one very special country with a lot of talking animals and fauns and dwarves etc. In this revised world, with a great human empire to the south of Narnia and human principality just next door, the White Witch would not have suspected Edmund of being a dwarf who shaved his beard – there would be far more simple and obvious explanations for his origin. And in fact, in this revised world it is not entirely clear why were the four Pevensie children singled out for the Thrones of Narnia, over so many other humans in the world. […] Still, we just have to live with these discrepancies, and enjoy each Narnia book on its own merits. "[86]

Accusations of gender stereotyping[edit]

In later years, both Lewis and theChronicleshave been criticised (often by other authors of fantasy fiction) forgender rolestereotyping, though other authors have defended Lewis in this area. Most allegations ofsexismcentre on the description of Susan Pevensie inThe Last Battlewhen Lewis writes that Susan is "no longer a friend of Narnia" and interested "in nothing nowadays except nylons and lipstick and invitations".

Philip Pullman,inimical to Lewis on many fronts, calls theNarniastories "monumentally disparaging of women".[87]His interpretation of the Susan passages reflects this view:

Susan, likeCinderella,is undergoing a transition from one phase of her life to another. Lewis didn't approve of that. He didn't like women in general, orsexualityat all, at least at the stage in his life when he wrote the Narnia books. He was frightened and appalled at the notion of wanting to grow up.[88]

In fantasy authorNeil Gaiman's short story "The Problem of Susan" (2004),[89][90][91]an elderly woman, Professor Hastings, deals with the grief and trauma of her entire family's death in a train crash. Although the woman's maiden name is not revealed, details throughout the story strongly imply that this character is the elderly Susan Pevensie. The story is written for an adult audience and deals with issues of sexuality and violence and through it Gaiman presents a critique of Lewis's treatment of Susan, as well as theproblem of evilas it relates to punishment and salvation.[90]

Lewis supporters cite the positive roles of women in the series, including Jill Pole inThe Silver Chair,Aravis Tarkheena inThe Horse and His Boy,Polly Plummer inThe Magician's Nephew,and particularly Lucy Pevensie inThe Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe.Alan Jacobs,an English professor atWheaton College,asserts that Lucy is the most admirable of the human characters and that generally the girls come off better than the boys throughout the series (Jacobs, 2008: 259)[citation not found].[92][unreliable source?][93][unreliable source?]In her contribution toThe Chronicles of Narnia and Philosophy,Karin Fry, an assistant professor of philosophy at theUniversity of Wisconsin,Stevens Point, notes that "the most sympathetic female characters inThe Chroniclesare consistently the ones who question the traditional roles of women and prove their worth to Aslan through actively engaging in the adventures just like the boys. "[94]Fry goes on to say:

The characters have positive and negative things to say about both male and female characters, suggesting an equality between sexes. However, the problem is that many of the positive qualities of the female characters seem to be those by which they can rise above their femininity... The superficial nature of stereotypical female interests is condemned.[94]

Nathan Ross notes that "Much of the plot of 'Wardrobe' is told exclusively from the point of view of Susan and Lucy. It is the girls who witness Aslan being killed and coming back to life – a unique experience from which the boys are excluded. Throughout, going through many highly frightening and shocking moments, Susan and Lucy behave with grown up courage and responsibility. Their experiences are told in full, over several chapters, while what the boys do at the same time – preparing an army and going into battle – is relegated to the background. This arrangement of material clearly implies that what girls saw and did was the more important. Given the commonly held interpretation – that Aslan is Jesus Christ and that what the girls saw was a no less than a reenacting of the Crucifixion – this order of priorities makes perfect sense".[95]

Taking a different stance altogether, Monika B. Hilder provides a thorough examination of the feminine ethos apparent in each book of the series, and proposes that critics tend to misread Lewis's representation of gender. As she puts it "...we assume that Lewis is sexist when he is in fact applauding the 'feminine' heroic. To the extent that we have not examined our own chauvinism, we demean the 'feminine' qualities and extol the 'masculine' – not noticing that Lewis does the opposite."[96]

Accusations of racism[edit]

In addition to sexism, Pullman and others have also accused the Narnia series of fostering racism.[87][97]Over the alleged racism inThe Horse and His Boy,newspaper editorKyrie O'Connorwrote:

While the book's storytelling virtues are enormous, you don't have to be a bluestocking ofpolitical correctnessto find some of this fantasy anti-Arab,or anti-Eastern, or anti-Ottoman.With all its stereotypes, mostly played for belly laughs, there are moments you'd like to stuff this story back into its closet.[98]

Gregg Easterbrook,writing inThe Atlantic,stated that "the Calormenes, are unmistakable Muslim stand-ins",[99]while novelistPhilip Hensherraises specific concerns that a reader might gain the impression that Islam is a "Satanic cult".[100]In rebuttal to this charge, at an address to a C. S. Lewis conference, Devin Brown argued that there are too many dissimilarities between the Calormene religion and Islam, particularly in the areas of polytheism and human sacrifice, for Lewis's writing to be regarded as critical of Islam.[101]

Nicholas Wanberg has argued, echoing claims by Mervyn Nicholson, that accusations of racism in the books are "an oversimplification", but he asserts that the stories employ beliefs about human aesthetics, including equating dark skin with ugliness, that have been traditionally associated with racist thought.[102]

Critics also argue whether Lewis's work presents a positive or negative view ofcolonialism.Nicole DuPlessis favors the anticolonial view, claiming "the negative effects of colonial exploitations and the themes of animals' rights and responsibility to the environment are emphasized in Lewis's construction of a community of living things. Through the negative examples of illegitimate rulers, Lewis constructs the 'correct' relationship between humans and nature, providing examples of rulers like Caspian who fulfil their responsibilities to the environment."[103]Clare Etcherling counters with her claim that "those 'illegitimate' rulers are often very dark-skinned" and that the only "legitimate rulers are those sons and daughters ofAdam and Evewho adhere to Christian conceptions of morality and stewardship – either white English children (such as Peter) or Narnians who possess characteristics valued and cultivated by the British (such as Caspian). "[104]

Adaptations[edit]

Television[edit]

Various books fromThe Chronicles of Narniahave been adapted for television over the years.

The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobewas firstadapted in 1967.Comprising ten episodes of thirty minutes each, the screenplay was written byTrevor Preston,and directed by Helen Standage.

The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobewasadapted again in 1979,this time as an animated cartoon co-produced byBill Melendezand theChildren's Television Workshop,with a screenplay by David D. Connell.

Between 1988 and 1990, the first four books (as published) were adapted by the BBC asthree TV serials.They were also aired in America on the PBS/Disney showWonderWorks.[105]They were nominated for a total of 16 awards, including an Emmy for "Outstanding Children's Program"[106]and a number ofBAFTAawards including Best Children's Programme (Entertainment/Drama) in 1988, 1989 and 1990.[107][108][109]

Film[edit]

Walden Media[edit]

Sceptical that any cinematic adaptation could render the more fantastical elements and characters of the story realistically,[110][failed verification]Lewis never sold the film rights to theNarniaseries.[111][failed verification]In answering a letter with a question posed by a child in 1957, asking if the Narnia series could please be on television, C. S. Lewis wrote back: "They'd be no good on TV. Humanised beasts can't be presented to theeyewithout at once becoming either hideous or ridiculous. I wish the idiots who run the film world [would] realize that there are stories which are for theearalone. "[112][citation not found]

The first novel adapted wasThe Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe.Released in December 2005,The Chronicles of Narnia: The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobewas produced byWalden Media,distributed byWalt Disney Pictures,and directed byAndrew Adamson,with a screenplay by Ann Peacock, Stephen McFeely and Christopher Markus. The second novel adapted wasThe Chronicles of Narnia: Prince Caspian.Released in 2008, it was co-produced byWalden MediaandWalt Disney Pictures,co-written and directed byAndrew Adamson,with Screenwriters includingChristopher Markus & Stephen McFeely.In December 2008, Disney pulled out of financing the remainder of theChronicles of Narniafilm series.[113][114]However, Walden Media and20th Century Foxeventually co-producedThe Chronicles of Narnia: The Voyage of the Dawn Treader,which was released in December 2010.

In May 2012, producerDouglas Greshamconfirmed that Walden Media's contract with the C.S. Lewis Estate had expired, and that there was a moratorium on producing anyNarniafilms outside of Walden Media.[115]On 1 October 2013, it was announced that the C.S. Lewis Company had entered into an agreement with theMark GordonCompany to jointly develop and produceThe Chronicles of Narnia: The Silver Chair.[116]On 26 April 2017,Joe Johnstonwas hired to direct the film.[117]In October, Johnston said filming is expected to begin in late 2018. In November 2018, these plans were halted becauseNetflixhad begun developing adaptations of the entire series.[118][119]

Netflix[edit]

On 3 October 2018, the C.S. Lewis Company announced thatNetflixhad acquired the rights to new film and television series adaptations of theNarniabooks.[120]According toFortune,this was the first time that rights to the entireNarniacatalogue had been held by a single company.[121]Entertainment One,which had acquired production rights to a fourthNarniafilm, also joined the series.Mark Gordon,Douglas Gresham and Vincent Sieber were announced as executive producers.[122]

Radio[edit]

TheBBCproduced dramatisations of all seven novels starting in the late 1980s and running into the 90s starringMaurice Denhamas Professor Kirke. They were Originally broadcast onBBC Radio 4In the UK. BBC Audiobooks released both audio cassette and compact disc versions of the series.[citation needed]

Between 1998 and 2002, Focus on the Family produced radio dramatisations byPaul McCuskerof the entire series through itsRadio Theatreprogramme.[123]Over one hundred performers took part includingPaul Scofieldas the storyteller andDavid Suchetas Aslan. Accompanied by an original orchestral score and cinema-qualitydigital sounddesign, the series was hosted by Lewis's stepson Douglas Gresham and ran for just over 22 hours. Recordings of the entire adaptation were released on compact disc between 1999 and 2003.[citation needed]

Stage[edit]

Many stage adaptations ofThe Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobehave been produced over the years.

In 1984, Vanessa Ford Productions presentedThe Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobeat London's Westminster Theatre. Adapted by Glyn Robbins, the play was directed byRichard Williamsand designed by Marty Flood. The production was later revived at Westminster and The Royalty Theatre and went on tour until 1997. Productions of other tales fromThe Chronicleswere also staged, includingThe Voyage of the Dawn Treader(1986),The Magician's Nephew(1988) andThe Horse and His Boy(1990).[citation needed]

In 1997, Trumpets Inc., a Filipino Christian theatre and musical production company, produced a musical rendition of "The Lion, The Witch and The Wardrobe" that Douglas Gresham, Lewis's stepson (and co-producer of the Walden Media film adaptations), has openly declared that he feels is the closest to Lewis's intent. The book and lyrics were written by Jaime del Mundo and Luna Inocian, while the music was composed by Lito Villareal.[124][125]

TheRoyal Shakespeare CompanypremieredThe Lion, the Witch and the WardrobeinStratford-upon-Avonin 1998. The novel was adapted as a musical production by Adrian Mitchell, with music by Shaun Davey.[126]The show was originally directed by Adrian Noble and designed by Anthony Ward, with the revival directed by Lucy Pitman-Wallace. Well received by audiences, the production was periodically re-staged by the RSC for several years afterwards.[127]

In 2022, The Logos Theater, ofTaylors, South Carolina,created a stage adaptation ofThe Horse and His Boy,with later performances at theMuseum of the Bible[128]andArk Encounter.[129]

See also[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^"Narnia coin: Special The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe coin released".BBC Newsround.Retrieved3 July2024.

- ^Green & Hooper 2002,pp. 302–307.

- ^abcdLewis, C. S. (1982).On Stories: And Other Essays on Literature.Harcourt Brace Jovanovich. p.53.ISBN0-15-668788-7.

- ^abcdFord 2005,p. 24.

- ^Green & Hooper 2002,p. 311.

- ^Ford 2005,p. 106.

- ^Edwards, Owen Dudley (2007).British Children's Fiction in the Second World War.p.129.ISBN978-0-7486-1650-3.

- ^Green & Hooper 2002,p. 303.

- ^Lobdell, Jared(2016).Eight Children in Narnia: The Making of a Children's Story.Chicago, IL: Open Court. p. 63.ISBN978-0-8126-9901-2.

- ^Green & Hooper 2002,p. 306.

- ^Grundy, G. B. (1904)."Plate 8".Murray's small classical atlas.London: J. Murray.Retrieved20 November2019.

- ^Kelly, Clint (2006)."Dear Mr. Lewis".Response.29(1).Retrieved22 September2008.

The seven books of Narnia have sold more than 100 million copies in 30 languages, nearly 20 million in the last 10 years alone

- ^Edward, Guthmann (11 December 2005)."'Narnia' tries to cash in on dual audience ".San Francisco Chronicle.Archived fromthe originalon 15 May 2012.Retrieved22 September2008.

- ^GoodKnight, Glen H.(3 August 2010)."Narnia Editions & Translations".Archived fromthe originalon 3 March 2011.Retrieved6 September2010.

- ^Schakel 1979,p. 13.

- ^Ford 2005,p. 464.

- ^Green & Hooper 2002,p. 307.

- ^Green & Hooper 2002,p. 309.

- ^abcGreen & Hooper 2002,p. 310.

- ^Green & Hooper 2002,p. 313.

- ^Green & Hooper 2002,p. 314.

- ^Hooper, Walter(1979)."Outline of Narnian history so far as it is known".Past Watchful Dragons: The Narnian Chronicles of C. S. Lewis.New York: Macmillan Publishing Co. pp. 41–44.ISBN0-02-051970-2.

- ^Dorsett & Mead 1995.

- ^Ford 2005,pp. xxiii–xxiv.

- ^Brady, Erik (1 December 2005)."A closer look at the world ofNarnia".USA Today.Retrieved21 September2008.

- ^abSchakel 1979.

- ^Rilstone, Andrew."What Order Should I Read the Narnia Books in (And Does It Matter?)".The Life and Opinions of Andrew Rilstone, Gentleman.Archived fromthe originalon 30 November 2005.

- ^Ford 2005,p. 474.

- ^Hooper, Walter (1997).C.S. Lewis: A Companion & Guide.Fount.ISBN978-0-00-628046-0.

- ^"The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe by C. S. Lewis: Christian Allegory – Theme Analysis".LitCharts.com.SparkNotes.Retrieved10 May2020.

- ^Lewis, C.S. (1947).Miracles.London & Glasgow: Collins/Fontana. p. 46.

- ^Private collection, Patricia Baird

- ^Dorsett & Mead 1995,p. 67.

- ^Hooper 2007,p. 1245 – Letter to Anne Jenkins, 5 March 1961

- ^Ford 2005,p. 490.

- ^Ford 2005,p. 491.

- ^Lewis, C. S. (1990).Surprised by Joy.Fount Paperbacks. p. 14.ISBN0-00-623815-7.

- ^Wilson, Tracy V. (7 December 2005)."How Narnia Works".HowStuffWorks.Retrieved28 October2008.

- ^Trotter, Drew (11 November 2005)."What Did C. S. Lewis Mean, and Does It Matter?".Leadership U.Retrieved28 October2008.

- ^Huttar, Charles A.(22 September 2007).""Deep lies the sea-longing": inklings of home (1) ".Mythlore.

- ^Duriez, Colin (2004).A Field Guide to Narnia.InterVarsity Press. pp. 80, 95.

- ^Ward 2008.

- ^Ward 2008,p. 237.

- ^Ford 2005,p. 16.

- ^Ward 2008,p. 222.

- ^Barrett, Justin L. (2010)."Some Planets in Narnia: a quantitative investigation of thePlanet Narniathesis "(PDF).Seven: an Anglo-American literary review (Wheaton College).Retrieved28 April2018.

- ^Downing, David C. (2005).Into The Wardrobe: C.S. Lewis and the Narnia Chronicles.Jossey Bass. pp.12–13.ISBN978-0-7879-7890-7.

- ^Johnson, William C.; Houtman, Marcia K. (1986)."Platonic Shadows in C. S. Lewis' Narnia Chronicles".Modern Fiction Studies.32(1): 75–87.doi:10.1353/mfs.0.1154.S2CID162284034.Retrieved1 October2018.

- ^Hardy 2007,pp. 20–25.

- ^Hardy 2007,pp. 30–34.

- ^Hardy 2007,pp. 38–41.

- ^abLindskoog, Kathryn Ann (1997).Journey into Narnia: C. S. Lewis's Tales Explored.Hope Publishing House. p. 87.ISBN0-932727-89-1.

- ^Walsh, Chad (1974).C. S. Lewis: Apostle to the Skeptics.Norwood Editions. p. 10.ISBN0-88305-779-4.

- ^Daigle-Williamson 2015,p. 5.

- ^Daigle-Williamson 2015,p. 162-170.

- ^Daigle-Williamson 2015,p. 170-174.

- ^Duriez, Colin(2015).Bedeviled: Lewis, Tolkien and the Shadow of Evil.Downers Grove, IL: IVP Books. pp. 180–182.ISBN978-0-8308-3417-4.

- ^"CS Lewis, Chronicles of Narnia author, honoured in Poets' corner".The Telegraph. Retrieved 24 February 2013

- ^"CS Lewis to be honoured in Poets' Corner".BBC News. Retrieved 23 November 2012

- ^Poskanzer, Susan Cornell (May 1976). "Thoughts on C. S. Lewis and the Chronicles of Narnia".Language Arts.53(5): 523–526.

- ^Miller, Laura (26 December 2005)."Far From Narnia".The New Yorker.

- ^Young, Cathy(March 2008)."A Secular Fantasy – The flawed but fascinating fiction of Philip Pullman".Reason.

- ^Chattaway, Peter T. (December 2007)."The Chronicles of Atheism".Christianity Today.

- ^Paterson, Katherine (2005). "Questions for Katherine Paterson".Bridge to Terabithia.Harper Trophy.

- ^Egan, Greg (12 November 2000)."Oracle".

- ^"Decatur Book Festival: Fantasy and its practice « PWxyz".Publishers Weekly blog.Archived fromthe originalon 11 September 2010.

- ^abRenton, Jennie (28 November 2001). "The story behind the Potter legend".The Sydney Morning Herald.

- ^McGrath, Charles (13 November 2005)."The Narnia Skirmishes".The New York Times.Retrieved29 May2008.

- ^"Artist weaves faith into acclaimed comics".Lubbockonline.com. Archived fromthe originalon 27 September 2015.Retrieved17 January2019.

- ^Richard Lea (19 March 2019)."Francis Spufford pens unauthorised Narnia novel".The Guardian.Retrieved21 March2019.

- ^Jensen, Jeff, (20 February 2008) "'Lost': Mind-Blowing Scoop From Its ProducersArchived29 November 2014 at theWayback Machine",Entertainment Weekly.Retrieved 29 October 2008.

- ^Irwin, William (2010).Ultimate Lost and Philosophy Volume 35 of The Blackwell Philosophy and Pop Culture Series.John Wiley and Sons. p. 368.ISBN9780470632291.

- ^Levin, Josh (23 December 2005)."The Chronicles of Narnia Rap".Slate.Retrieved19 December2010.

- ^Brennan, Herbie (2010).Through the Wardrobe: Your Favorite Authors on C. S. Lewis's Chronicles of Narnia.BenBella Books. p. 6.ISBN9781935251682.

- ^"Digimon RPG".Gamers Hell.Retrieved26 July2010.

- ^Rosner, Helen (8 July 2018)."'No Reservations: Narnia,' a Triumph of Anthony Bourdain Fan Fiction ".New Yorker.Retrieved29 March2024.

- ^Carpenter,The Inklings,p.42-45. See also Lewis's own autobiographySurprised by Joy

- ^Root, Jerry; Martindale, Wayne (12 March 2012).The Quotable Lewis.Tyndale House Publishers, Inc. pp. 59–.ISBN978-1-4143-5674-7.

- ^Friskney, Paul (2005).Sharing the Narnia Experience: A Family Guide to C. S. Lewis's the Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe.Standard Publishing. pp. 12–.ISBN978-0-7847-1773-8.

- ^Chattaway, Peter T."Narnia 'baptizes' – and defends – pagan mythology".Canadian Christianity.

- ^Kjos, Berit (December 2005)."Narnia: Blending Truth and Myth".Crossroad.Kjos Ministries.

- ^Hurst, Josh (5 December 2005)."Nine Minutes of Narnia".Christianity TodayMovies.Archived fromthe originalon 12 March 2008.

- ^"C.S. Lewis, the Sneaky Pagan".Christianity Today.1 June 2004. Archived fromthe originalon 26 May 2011.

- ^"The paganism of Narnia".Canadian Christianity.

- ^See essay "Is Theism Important?" inLewis, C. S.(15 September 2014).Hooper, Walter(ed.).God in the Dock.William B. Eerdmans Publishing. pp. 186–.ISBN978-0-8028-7183-1.

- ^Ward, Gertrude. "Narnia Revisited". In Wheately, Barbara (ed.).Academic Round Table to Re-Examine 20th Century Children's Literature.

- ^abEzard, John (3 June 2002)."Narnia books attacked as racist and sexist".The Guardian.Archived fromthe originalon 8 February 2015.Retrieved26 March2015.

- ^Pullman, Philip(2 September 2001)."The Dark Side of Narnia".The Cumberland River Lamppost.Archived fromthe originalon 16 November 2010.Retrieved10 December2005.

- ^Gaiman, Neil(2004). "The Problem of Susan". In Sarrantonio, Al (ed.).Flights: Extreme Visions of Fantasy Volume II.New York: New American Library.ISBN978-0-451-46099-8.

- ^abWagner, Hank; Golden, Christopher; Bissette, Stephen R. (28 October 2008).Prince of Stories: The Many Worlds of Neil Gaiman.St. Martin's Press. pp. 395–.ISBN978-1-4299-6178-3.

- ^Neil Gaiman (9 February 2010).Fragile Things: Short Fictions and Wonders.HarperCollins.ISBN978-0-06-051523-2.

- ^Anderson, RJ (30 August 2005)."The Problem of Susan".

- ^Rilstone, Andrew (30 November 2005)."Lipstick on My Scholar".

- ^abFry, Karin (2005). "13: No Longer a Friend of Narnia: Gender in Narnia". In Bassham, Gregory; Walls, Jerry L. (eds.).The Chronicles of Narnia and Philosophy: The Lion, the Witch and the Worldview.Chicago and La Salle, Illinois: Open Court.

- ^Nathan Vernon Ross, "Narnia Revisited" in "Is Children's Literature Intended Only For Children?", 2002 essay collection edited by Cynthia McDowel, p. 185-197

- ^Hilder, Monika B. (2012).The Feminine Ethos in C. S. Lewis's Chronicles of Narnia.New York: Peter Lang. p. 160.ISBN978-1-4331-1817-3.

- ^"Pullman attacks Narnia film plans".BBC News.16 October 2005.

- ^O'Connor, Kyrie (1 December 2005)."5th Narnia book may not see big screen".Houston Chronicle.IndyStar.com. Archived fromthe originalon 14 December 2005.

- ^Easterbrook, Gregg (1 October 2001)."In Defense of C. S. Lewis".The Atlantic.Retrieved21 March2020.

- ^Hensher, Philip(1 March 1999)."Don't let your children go to Narnia: C. S. Lewis's books are racist and misogynist".Discovery Institute.

- ^Brown, Devin (28 March 2009)."Are The Chronicles of Narnia Sexist and Racist?".Keynote Address at The 12th Annual Conference of The C. S. Lewis and Inklings Society Calvin College.NarniaWeb.

- ^Wanberg, Nicholas (2013)."Noble and Beautiful: Race and Human Aesthetics in C. S. Lewis's The Chronicles of Narnia".Fafnir: Nordic Journal of Science Fiction and Fantasy Research.1(3).Retrieved28 October2015.

- ^DuPlessis, Nicole (2004). "EcoLewis: Conversationism and Anticolonialism in the Chronicles of Narnia". In Dobrin, Sidney I.; Kidd, Kenneth B. (eds.).Wild Things: Children's Culture and Ecocriticism.Detroit: Wayne State University Press. p. 125.

- ^Echterling, Clare (2016). "Postcolonial Ecocriticism, Classic Children's Literature, and the Imperial-Environmental Imagination in The Chronicles of Narnia".The Journal of the Midwest Modern Language Association.49(1): 102.

- ^"Wonderworks Family Movie Series".movieretriever.com.Archived fromthe originalon 3 April 2012.

- ^"The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe Wonderworks".Television Academy.Retrieved8 July2021.

- ^"1989 Television Children's Programme – Entertainment/Drama | BAFTA Awards".awards.bafta.org.Retrieved8 July2021.

- ^"BAFTA Awards".awards.bafta.org.1990.Retrieved8 July2021.

- ^"BAFTA Awards".awards.bafta.org.1991.Retrieved8 July2021.

- ^Hooper 2007,p. 361 – Letter to Warren Lewis, 3 March 1940

- ^All My Road Before Me,1 June 1926, p. 405

- ^Patricia Baird, private collection

- ^Sanford, James (24 December 2008)."Disney No Longer Under Spell of Narnia".

- ^"Disney opts out of 3rd 'Narnia' film".Orlando Business Journal.29 December 2008.Retrieved27 March2011.

- ^"Gresham Shares Plans for Next Narnia Film".NarniaWeb.Retrieved19 November2017.

- ^McNary, Dave (1 October 2013)."Mark Gordon Producing Fourth 'Narnia' Movie".Variety.Retrieved3 November2017.

- ^Kroll, Justin (26 April 2017)."'Captain America' Director Joe Johnston Boards 'Narnia' Revival 'The Silver Chair' (Exclusive) ".Variety.Retrieved3 November2017.

- ^"The Silver Chair to Begin Filming 2018, Johnston Says".NarniaWeb.Retrieved3 November2017.

- ^Beatrice Verhoeven (3 October 2018)."Netflix to Develop Series, Films Based on CS Lewis' 'The Chronicles of Narnia'".the wrap.Retrieved28 November2018.

- ^Beatrice Verhoeven (3 October 2018)."Netflix to Develop Series, Films Based on CS Lewis' 'The Chronicles of Narnia'".the wrap.Retrieved3 October2018.

- ^Jenkins, Aric (1 November 2018). "Netflix Looks in the Wardrobe to Find a Fantasy Hit".Fortune(Paper).178(5): 19.

- ^Andreeva, Nellie (3 October 2018)."Netflix To Develop 'The Chronicles of Narnia' TV Series & Films".Retrieved3 October2018.

- ^Wright, Greg."Reviews by Greg Wright – Narnia Radio Broadcast".Archived fromthe originalon 10 July 2005.Retrieved31 March2011.

- ^Garceau, Scott; Garceau, Therese (14 October 2012)."The Stepson of Narnia".The Philippine Star.Retrieved9 July2015.

- ^Simpson, Paul (2013).A Brief Guide to C. S. Lewis: From Mere Christianity to Narnia.Little, Brown Book Group.ISBN978-0762450763.Retrieved9 July2015.

- ^Cavendish, Dominic (21 November 1998)."Theatre: The Lion, The Witch And The Wardrobe".The Independent.Retrieved31 March2011.

- ^Melia, Liz (9 December 2002)."Engaging fairytale is sure to enchant all".BBC.Retrieved31 March2011.

- ^Stoltenberg, John (19 January 2023)."Live theater returns to a gem of a venue at the Museum of the Bible".DC Theater Arts.Retrieved20 January2024.

- ^"Presentations".

References[edit]

- Daigle-Williamson, Marsha (2015).Reflecting the Eternal: Dante's Divine Comedy in the Novels of C. S. Lewis.Peabody, MA: Hendrickson Publishers.ISBN978-1-61970-665-1.

- Dorsett, Lyle W.; Mead, Marjorie Lamp (1995).C. S. Lewis: Letters to Children.Touchstone.ISBN0-684-82372-1.

- Ford, Paul (2005).Companion to Narnia: A Complete Guide to the Magical World of C.S. Lewis's The Chronicles of Narnia(Revised ed.). San Francisco: Harper.ISBN978-0-06-079127-8.

- Green, Roger Lancelyn;Hooper, Walter(2002).C. S. Lewis: A Biography(Fully revised & expanded ed.). HarperCollins.ISBN0-00-715714-2.

- Hardy, Elizabeth Baird (2007).Milton, Spenser and The Chronicles of Narnia: literary sources for the C. S. Lewis novels.McFarland & Company, Inc.ISBN978-0-7864-2876-2.

- Hooper, Walter(2007).The Collected Letters of C. S. Lewis, Volume III.HarperSanFrancisco.ISBN978-0-06-081922-4.

- Schakel, Peter (1979).Reading with the Heart: The Way into Narnia.Grand Rapids: William B. Eerdmans.ISBN978-0-8028-1814-0.