Constitution of India

| Constitution of India | |

|---|---|

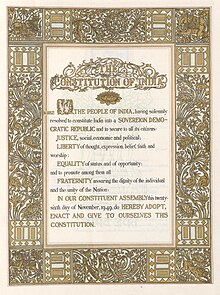

Original textof thepreamble | |

| Overview | |

| Jurisdiction | |

| Ratified | 26 November 1949 |

| Date effective | 26 January 1950 |

| System | Federalparliamentaryconstitutional republic |

| Government structure | |

| Branches | Three (Executive, Legislature and Judiciary) |

| Head of state | President of India |

| Chambers | Two(Rajya SabhaandLok Sabha) |

| Executive | Prime Minister of India–led cabinet responsible to thelower houseof theparliament |

| Judiciary | Supreme court,high courtsanddistrict courts |

| Federalism | Federal[1] |

| Electoral college | Yes,forpresidentialandvice presidential elections |

| Entrenchments | 2 |

| History | |

| Amendments | 106 |

| Last amended | 28 September 2023 (106th) |

| Citation | Constitution of India(PDF),9 September 2020, archived fromthe original(PDF)on 29 September 2020 |

| Location | Samvidhan Sadan,New Delhi,India |

| Signatories | 284 members of the Constituent Assembly |

| Supersedes | Government of India Act 1935 Indian Independence Act 1947 |

| Part ofa serieson the |

| Constitution of India |

|---|

|

| Preamble |

TheConstitution of Indiais the supremelegal document of India.[2][3]The document lays down the framework that demarcates fundamental political code, structure, procedures, powers, and duties of government institutions and sets outfundamental rights,directive principles,and the duties of citizens. It is the longest written national constitution in the world.[4][5][6]

It impartsconstitutional supremacy(notparliamentary supremacy,since it was created by aconstituent assemblyrather thanParliament) and was adopted by its people with a declaration inits preamble.Parliament cannotoverride the constitution.

It was adopted by theConstituent Assembly of Indiaon 26 November 1949 and became effective on 26 January 1950.[7]The constitution replaced theGovernment of India Act 1935as the country's fundamental governing document, and theDominion of Indiabecame theRepublic of India.To ensureconstitutional autochthony,its framers repealed prior acts of theBritish parliamentin Article 395.[8]India celebrates its constitution on 26 January asRepublic Day.[9]

The constitution declares India asovereign,socialist,secular,[10]anddemocraticrepublic,assures its citizensjustice,equality,andliberty,and endeavours to promotefraternity.[11]The original 1950 constitution is preserved in anitrogen-filled case at theOld Parliament HouseinNew Delhi.[12]

Background

In 1928, theAll Parties Conferenceconvened a committee inLucknowto prepare the Constitution of India, which was known as theNehru Report.[13]

With the exception of scatteredFrenchandPortugueseexclaves,Indiawas under theBritish rulefrom 1858 to 1947. From 1947 to 1950, the same legislation continued to be implemented as India was adominionofUnited Kingdomfor these three years, as each princely state was convinced bySardar PatelandV. P. Menonto sign thearticles of integrationwith India, and the British Government continued to be responsible for the external security of the country.[14]Thus, the constitution of India repealed theIndian Independence Act 1947andGovernment of India Act 1935when it became effective on 26 January 1950. India ceased to be adominionof theBritish Crownand became a sovereign, democratic republic with the constitution. Articles 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 60, 324, 366, 367, 379, 380, 388, 391, 392, 393, and 394 of the constitution came into force on 26 November 1949, and the remaining articles became effective on 26 January 1950 which is celebrated every year in India asRepublic Day.[15]

Previous legislation

The constitution was drawn from a number of sources. Mindful of India's needs and conditions, its framers borrowed features of previous legislation such as theGovernment of India Act 1858,theIndian Councils Acts of 1861,1892and1909,the Government of India Acts1919and1935,and theIndian Independence Act 1947.The latter, which led to the creation ofPakistan,divided the former Constituent Assembly in two. The Amendment act of 1935 is also a very important step for making the constitution for two new born countries. Each new assembly had sovereign power to draft and enact a new constitution for the separate states.[16]

Constituent Assembly

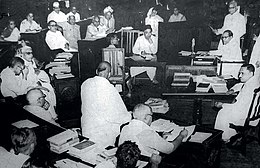

The constitution was drafted by theConstituent Assembly,which was elected by elected members of theprovincial assemblies.[17]The 389-member assembly (reduced to 299 after thepartition of India) took almost three years to draft the constitution holding eleven sessions over a 165-day period.[4][16]

In the constitution assembly, a member of the drafting committee,T. T. Krishnamacharisaid:

Mr. President, Sir, I am one of those in the House who have listened to Dr. Ambedkar very carefully. I am aware of the amount of work and enthusiasm that he has brought to bear on the work of drafting this Constitution. At the same time, I do realise that that amount of attention that was necessary for the purpose of drafting a constitution so important to us at this moment has not been given to it by the Drafting Committee. The House is perhaps aware that of the seven members nominated by you, one had resigned from the House and was replaced. One died and was not replaced. One was away in America and his place was not filled up and another person was engaged in State affairs, and there was a void to that extent. One or two people were far away from Delhi and perhaps reasons of health did not permit them to attend. So it happened ultimately that the burden of drafting this constitution fell on Dr. Ambedkar and I have no doubt that we are grateful to him for having achieved this task in a manner which is undoubtedly commendable.[18][19]

B. R. Ambedkarin his concluding speech in constituent assembly on 25 November 1949 stated that:[20]

The credit that is given to me does not really belong to me. It belongs partly to Sir B.N. Rau the Constitutional Advisor to the Constituent Assembly who prepared a rough draft of the Constitution for the consideration of Drafting Committee. A part of the credit must go to the members of the Drafting Committe who, as I have said, have sat for 141 days and without whose ingenuity to devise new formulae and capacity to tolerate and to accomodate different points of view, the task of framing the Constitution could not have come to so successful a conclusion. Much greater share of the credit must go to Mr. S. N. Mukherjee, the Chief Draftsman of the Constitution. His ability to put the most intricate proposals in the simplest and clearest legal form can rarely be equalled, nor his capacity for hard work. He has been an acquisition to the Assembly. Without his help this Assembly would have taken many more years to finalise the Constitution. I must not omit to mention the members of the staff working under Mr. Mukherjee. For, I known how hard they worked and how long they have toiled sometimes even beyond midnight. I want to thank them all for their effort and their co-operation.

While deliberating the revised draft constitution, the assembly moved, discussed and disposed off 2,473 amendments out of a total of 7,635.[16][21]

Timeline of formation of the Constitution of India

- 6 December 1946:Formation of the Constitution Assembly (in accordance with French practice).[22]

- 9 December 1946:The first meeting was held in the constitution hall (now theCentral Hall of Parliament House).[22][23]The 1st person to address wasJ. B. Kripalani,Sachchidananda Sinhabecame temporary president. (Demanding a separate state, the Muslim League boycotted the meeting.)[24]

- 11 December 1946:The Assembly appointedRajendra Prasadas its president,[23]H. C. Mukherjeeas its vice-president and,B. N. Rauas constitutional legal adviser. (There were initially 389 members in total, which declined to 299 afterpartition,out of the 389 members, 292 were from government provinces, four from chief commissioner provinces and 93 from princely states.)

- 13 December 1946:An "Objective Resolution" was presented byJawaharlal Nehru,[23]laying down the underlying principles of the constitution. This later became the Preamble of the Constitution.

- 22 January 1947:Objective resolution unanimously adopted.[23]

- 22 July 1947:National flagadopted.[25]

- 15 August 1947:Achieved independence. India split into theDominion of Indiaand theDominion of Pakistan.[22]

- 29 August 1947:Drafting Committee appointed withB. R. Ambedkaras its chairman.[23]The other six members of committee wereK.M. Munshi,Muhammed Sadulla,Alladi Krishnaswamy Iyer,N. Gopalaswami Ayyangar,Devi Prasad Khaitan[26]and BL Mitter.[27]

- 16 July 1948:Along withHarendra Coomar Mookerjee,V. T. Krishnamachariwas also elected as second vice-president of Constituent Assembly.[28]

- 26 November 1949:The Constitution of India was passed and adopted by the assembly.[23]

- 24 January 1950:Last meeting of Constituent Assembly. The Constitution was signed and accepted (with 395 Articles, 8 Schedules, and 22 Parts).[29]

- 26 January 1950:The Constitution came into force. (The process took 2 years, 11 months and 18 days[22]—at a total expenditure of ₹6.4 million to finish.)[30]

G. V. Mavlankarwas the firstSpeaker of the Lok Sabha(the lower house of Parliament) after India turned into a republic.[31]

Membership

B. R. Ambedkar,Sanjay Phakey,Jawaharlal Nehru,C. Rajagopalachari,Rajendra Prasad,Vallabhbhai Patel,Kanaiyalal Maneklal Munshi,Ganesh Vasudev Mavalankar,Sandipkumar Patel,Abul Kalam Azad,Shyama Prasad Mukherjee,Nalini Ranjan Ghosh,andBalwantrai Mehtawere key figures in the assembly,[4][16]which had over 30 representatives of thescheduled classes.Frank Anthonyrepresented theAnglo-Indian community,[4]and theParsiswere represented by H. P. Modi.[4]Harendra Coomar Mookerjee,a Christian assembly vice-president, chaired the minorities committee and represented non-Anglo-Indian Christians.[4]Ari Bahadur Gurung represented the Gorkha community.[4]Judges, such asAlladi Krishnaswamy Iyer,Benegal Narsing Rau,K. M. MunshiandGanesh Mavlankarwere members of the assembly.[4]Female members includedSarojini Naidu,Hansa Mehta,Durgabai Deshmukh,Amrit KaurandVijaya Lakshmi Pandit.[4]

The first, two-day president of the assembly wasSachchidananda Sinha;Rajendra Prasadwas later elected president.[16][17]It met for the first time on 9 December 1946.[4][17][32]

Drafting

SirB. N. Rau,acivil servantwho became the firstIndian judgein theInternational Court of Justiceand waspresident of the United Nations Security Council,was appointed as the assembly's constitutional adviser in 1946.[33]Responsible for the constitution's general structure, Rau prepared its initial draft in February 1948.[33][34][35]The draft of B.N. Rau consisted of 243 articles and 13 schedules which came to 395 articles and 8 schedules after discussions, debates and amendments.[36]

At 14 August 1947 meeting of the assembly, committees were proposed.[17]Rau's draft was considered, debated and amended by the eight-person drafting committee, which was appointed on 29 August 1947 withB. R. Ambedkaras chair.[4][32]A revised draft constitution was prepared by the committee and submitted to the assembly on 4 November 1947.[32]

Before adopting the constitution, the assembly held eleven sessions in 165 days.[4][16]On 26 November 1949, it adopted the constitution,[4][16][32][35][37]which was signed by 284 members.[4][16][32][35][37]The day is celebrated as National Law Day,[4][38]orConstitution Day.[4][39]The day was chosen to spread the importance of the constitution and to spread thoughts and ideas of Ambedkar.[40]

The assembly's final session convened on 24 January 1950. Each member signed two copies of the constitution, one inHindiand the other in English.[4][16][35]The original constitution is hand-written, with each page decorated by artists fromShantiniketanincludingBeohar Rammanohar SinhaandNandalal Bose.[32][35]ItscalligrapherwasPrem Behari Narain Raizada.[32]The constitution was published inDehradunandphotolithographedby theSurvey of India.Production of the original constitution took nearly five years. Two days later, on 26 January 1950, it became the law ofIndia.[32][41]The estimated cost of the Constituent Assembly was₹6.3crore.[16]The constitution has hadmore than 100 amendmentssince it was enacted.[42]

Influence of other constitutions

| Government | Influence |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

|

Structure

| Part ofa serieson the |

| Constitution of India |

|---|

|

| Preamble |

The Indian constitution is the world's longest for a sovereign nation.[4][5][6]At its enactment, it had 395 articles in 22 parts and 8 schedules.[a][16]At about 145,000 words, it is the second-longest active constitution—after theConstitution of Alabama—in the world.[47]

The amended constitution has a preamble and 470 articles,[b]which are grouped into 25 parts.[c][32]With 12 schedules[d]and five appendices,[32][48]it has been amended105 times;thelatest amendmentbecame effective on 15 August 2021.

The constitution's articles are grouped into the following parts:

- Preamble,[49]with the words "socialist", "secular" and 'integrity' added in 1976 by the 42nd amendment[50][51]

- Part I[52]–The Union and its Territory– Articles 1 to 4

- Part II–Citizenship– Articles 5 to 11

- Part III–Fundamental Rights– Articles 12 to 35

- Part IV–Directive Principles of State Policy– Articles 36 to 51

- Part IVA–Fundamental Duties– Article 51A

- Part V– The Union – Articles 52 to 151

- Part VI– The States – Articles 152 to 237

- Part VII– States in the B part of the first schedule(repealed)– Article 238

- Part VIII– Union Territories – Articles 239 to 242

- Part IX– Panchayats – Articles 243 to 243(O)

- Part IXA– Municipalities – Articles 243(P) to 243(ZG)

- Part IXB– Co-operative societies[53]– Articles 243(ZH) to 243(ZT)

- Part X– Scheduled and tribal areas – Articles 244 to 244A

- Part XI– Relations between the Union and the States – Articles 245 to 263

- Part XII– Finance,property,contracts and suits – Articles 264 to 300A

- Part XIII– Trade and commerce within India – Articles 301 to 307

- Part XIV– Services under the union and states – Articles 308 to 323

- Part XIVA– Tribunals – Articles 323A to 323B

- Part XV– Elections – Articles 324 to 329A

- Part XVI– Special provisions relating to certain classes – Articles 330 to 342

- Part XVII– Languages – Articles 343 to 351

- Part XVIII– Emergency provisions – Articles 352 to 360

- Part XIX– Miscellaneous – Articles 361 to 367

- Part XX– Amendment of the Constitution – Articles 368

- Part XXI– Temporary, transitional and special provisions – Articles 369 to 392

- Part XXII– Short title, date of commencement, authoritative text inHindiand repeals – Articles 393 to 395

Schedules

Schedules are lists in the constitution which categorise and tabulate bureaucratic activity and government policy.

| Schedule | Article(s) | Description |

|---|---|---|

| First | 1 and 4 | Lists India's states and territories, changes in their borders and the laws used to make that change. |

| Second | 59(3), 65(3), 75(6), 97, 125, 148(3), 158(3), 164(5), 186 and 221 | Lists the salaries of public officials, judges, and thecomptroller and auditor general. |

| Third | 75(4), 99, 124(6), 148(2), 164(3), 188 and 219 | Forms of oaths – Lists the oaths of office for elected officials and judges |

| Fourth | 4(1) and 80(2) | Details the allocation of seats in theRajya Sabha(upper house of Parliament) by state or union territory. |

| Fifth | 244(1) | Provides for the administration and control ofScheduled Areas[e]andScheduled Tribes[f](areas and tribes requiring special protection). |

| Sixth | 244(2) and 275(1) | Provisions made for the administration of tribal areas inAssam,Meghalaya,Tripura,andMizoram. |

| Seventh | 246 | Central government, state, and concurrent lists of responsibilities |

| Eighth | 344(1) and 351 | Official languages |

| Ninth | 31-B | Validation of certain acts and regulations.[g] |

| Tenth | 102(2) and 191(2) | Anti-defectionprovisions for members of Parliament and state legislatures. |

| Eleventh | 243-G | Panchayat Raj(rural local government) |

| Twelfth | 243-W | Municipalities(urban local government) |

Appendices

- Appendix I– The Constitution (Application to Jammu and Kashmir) Order, 1954

- Appendix II– Re-statement, referring to the constitution's present text, of exceptions and modifications applicable to the state of Jammu and Kashmir

- Appendix III– Extracts from the Constitution (Forty-fourth Amendment) Act, 1978

- Appendix IV– The Constitution (Eighty-sixth Amendment) Act, 2002

- Appendix V– The Constitution (Eighty-eighth Amendment) Act, 2003

Governmental sources of power

The executive, legislative, and judicial branches of government receive their power from the constitution and are bound by it.[54]With the aid of its constitution, India is governed by aparliamentary systemof government with theexecutivedirectly accountable to thelegislature.

- Under Articles 52 and 53: thepresident of Indiais head of the executive branch

- UnderArticle 60:the duty of preserving, protecting, and defending the constitution and the law.

- UnderArticle 74:theprime ministeris the head of theCouncil of Ministers,which aids and advises the president in the performance of their constitutional duties.

- Under Article 75(3): the Council of Ministers is answerable to thelower house.

The constitution is consideredfederalin nature, andunitaryin spirit. It has features of a federation, including acodified,supreme constitution; a three-tier governmental structure (central, state and local);division of powers;bicameralism;and an independentjudiciary.It also possesses unitary features such as a single constitution, singlecitizenship,an integrated judiciary, a flexible constitution, a strongcentral government,appointment ofstate governorsby the central government,All India Services(theIAS,IFSandIPS), andemergency provisions.This unique combination makes it quasi-federal in form.[55]

Each state andunion territoryhas its own government. Analogous to the president and prime minister, each has agovernoror (in union territories) alieutenant governorand achief minister.Article 356permits the president to dismiss a state government and assume direct authority if a situation arises in which state government cannot be conducted in accordance with constitution. This power, known aspresident's rule,was abused as state governments came to be dismissed on flimsy grounds for political reasons. AfterS. R. Bommai v. Union of India,[56][57]such a course of action is more difficult since the courts have asserted their right of review.[58]

The 73rd and 74th Amendment Acts introduced the system ofpanchayati rajin rural areas andNagar Palikasin urban areas.[32]Article 370gave special status to the state ofJammu and Kashmir.

The legislature and amendments

Article 368dictates the procedure forconstitutional amendments.Amendments are additions, variations or repeal of any part of the constitution by Parliament.[59]An amendment bill must be passed by each house of Parliament by a two-thirds majority of its total membership when at least two-thirds are present and vote. Certain amendments pertaining to the constitution's federal nature must also be ratified by a majority of state legislatures.

Unlike ordinary bills in accordance withArticle 245(except formoney bills), there is no provision for a joint session of theLok SabhaandRajya Sabhato pass a constitutional amendment. During a parliamentary recess, the president cannot promulgateordinancesunder his legislative powers underArticle 123, Chapter III.

Despite thesupermajorityrequirement for amendments to pass, the Indian constitution is the world's most frequently-amended national governing document.[60]The constitution is so specific in spelling out government powers that many amendments address issues dealt with by statute in other democracies.

In 2000, theJustice Manepalli Narayana Rao Venkatachaliah Commissionwas formed to examine a constitutional update. The commission submitted its report on 31 March 2002. However, the recommendations of this report have not been accepted by the consecutive governments.

Thegovernment of Indiaestablishes term-basedlaw commissionsto recommend legal reforms, facilitating the rule of law.

Limitations

InKesavananda Bharati v. State of Kerala,theSupreme Courtruled that an amendment cannot destroy what it seeks to modify; it cannot tinker with the constitution's basic structure or framework, which are immutable. Such an amendment will be declared invalid, although no part of the constitution is protected from amendment; the basic structure doctrine does not protect any one provision of the constitution. According to the doctrine, the constitution's basic features (when "read as a whole" ) cannot be abridged or abolished. These "basic features" have not been fully defined,[54]and whether a particular provision of the constitution is a "basic feature" is decided by the courts.[61]

TheKesavananda Bharati v. State of Keraladecision laid down the constitution's basic structure:[1]

- Supremacy of the constitution

- Republican, democratic form of government

- Its secular nature

- Separation of powers

- Its federal character[1]

This implies that Parliament can only amend the constitution to the limit of its basic structure. The Supreme Court or ahigh courtmay declare the amendment null and void if this is violated, after ajudicial review.This is typical of parliamentary governments, where the judiciary checks parliamentary power.

In its 1967Golak Nath v. State of Punjabdecision, the Supreme Court ruled that the state of Punjab could not restrict any fundamental rights protected by the basic structure doctrine.[62]The extent of land ownership and practice of a profession, in this case, were considered fundamental rights.[63]The ruling was overturned with the ratification of the 24th Amendment in 1971.[63]

The judiciary

The judiciary is the final arbiter of the constitution.[64]Its duty (mandated by the constitution) is to act as a watchdog, preventing any legislative or executive act from overstepping constitutional bounds.[65]The judiciary protects the fundamental rights of the people (enshrined in the constitution) from infringement by any state body, and balances the conflicting exercise of power between the central government and a state (or states).

The courts are expected to remain unaffected by pressure exerted by other branches of the state, citizens or interest groups. An independent judiciary has been held as a basic feature of the constitution,[66][67]which cannot be changed by the legislature or the executive.[68]Article 50 of the Constitution provides that the state must take measures to separate the judiciary from the executive in the public services.

Judicial review

Judicial reviewwas adopted by the constitution of India fromjudicial review in the United States.[69]In the Indian constitution,judicial reviewis dealt with inArticle 13.The constitution is the supreme power of the nation, and governs all laws. According toArticle 13:

- All pre-constitutional laws, if they conflict wholly or in part with the constitution, shall have all conflicting provisions deemed ineffective until an amendment to the constitution ends the conflict; the law will again come into force if it is compatible with the constitution as amended (the Doctrine of Eclipse).[70]

- Laws made after the adoption of the constitution must be compatible with it, or they will be deemed voidab initio.

- In such situations, the Supreme Court (or a high court) determines if a law is in conformity with the constitution. If such an interpretation is not possible because of inconsistency (and where separation is possible), the provision which is inconsistent with the constitution is considered void. In addition to Article 13, Articles 32, 226 and 227 provide the constitutional basis for judicial review.[71]

Due to the adoption of theThirty-eighth Amendment,the Supreme Court was not allowed to preside over any laws adopted during a state of emergency which infringefundamental rightsunder article 32 (the right to constitutional remedies).[72]TheForty-second Amendmentwidened Article 31C and added Articles 368(4) and 368(5), stating that any law passed by Parliament could not be challenged in court. The Supreme Court ruled inMinerva Mills v. Union of Indiathat judicial review is a basic characteristic of the constitution, overturning Articles 368(4), 368(5) and 31C.[73]

The executive

Chapter 1 of the Constitution of India creates aparliamentary system,with a Prime Minister who, in practice, exercises most executive power. The prime minister must have the support of a majority of the members of theLok Sabha,or lower House of Parliament. If the Prime Minister does not have the support of a majority, the Lok Sabha can pass a motion of no confidence, removing the Prime Minister from office. Thus the Prime Minister is the member of parliament who leads the majority party or a coalition comprising a majority.[74]The Prime Minister governs with the aid of aCouncil of Ministers,which the Prime Minister appoints and whose members head ministries. Importantly, Article 75 establishes that "the Council of Ministers shall becollectively responsibleto the House of the People "or Lok Sabha.[75]The Lok Sabha interprets this article to mean that the entire Council of Ministers can be subjected to a no confidence motion.[76]If a no confidence motion succeeds, the entire Council of Ministers must resign.

Despite the Prime Minister exercising executive power in practice, the constitution bestows all the national government's executive power in the office of the President.[77]This de jure power is not exercised in reality, however. Article 74 requires the President follow the "aid and advice" of the council, headed by the Prime Minister.[78]In practice, this means that President's role is mostly ceremonial, with the Prime Minister exercising executive power because the President is obligated to act on the Prime Minister's wishes.[79]The President does retain the power to ask the council to reconsider its advice, however, an action the President may take publicly. The council is not required to make any changes before resubmitting the advice to the President, in which case the President is constitutionally required to adhere to it, overriding the President's discretion.[78]Previous Presidents have used this occasion to make public statements about their reasoning for sending a decision back to the council, in an attempt to sway public opinion.[79]This system, with an executive who only possesses nominal power and an official "advisor" who possess actual power, is based on the British system and is a result of colonial influences on India before and during the writing of its constitution.[80][81]

The President is chosen by an electoral college composed of the members of both the national and state legislatures. Article 55 outlines the specifics of the electoral college. Half of the votes in the electoral college are assigned to state representatives in proportion to the population of each state and the other half are assigned to the national representatives. The voting is conducted using a secret,single transferable vote.[82]

While the Constitution gives the legislative powers to the two Houses of Parliament, Article 111 requires the President's signature for a bill to become law. Just as with the advice of the council, the President can refuse to sign and send it back to the Parliament, but the Parliament can in turn send it back to the President who must then sign it.[83]

Dismissal of the Prime Minister

Despite the President's mandate to obey the advice of the Prime Minister and the council, Article 75 declares that both "shall hold office during the pleasure of the President."[75]This means the President has the constitutional power to dismiss the Prime Minister or Council at anytime. If the Prime Minister still retained a majority vote in the Lok Sabha, however, this could trigger a constitutional crisis because the same article of the Constitution states that the Council of Ministers is responsible to the Lok Sabha and must command a majority in it. In practice the issue has never arisen, though PresidentZail Singhthreatened to remove Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi from office in 1987.[84]

Presidential power to legislate

When either or both Houses of Parliament are not in session, the Prime Minister, acting via the President, can unilaterally exercise the legislative power, creatingordinancesthat have the force of law. These ordinances expire six weeks after Parliament reconvenes or sooner if both Houses disapprove.[85]The Constitution declares that ordinances should only be issued when circumstances arise that require "immediate action." Because this term is not defined, governments have begun abusing the ordinance system to enact laws that could not pass both Houses of Parliament, according to some commentators.[86]This appears to be more common with divided government; when the Prime Minister's party controls the lower house but not the upper house, ordinances can be used to avoid needing the approval of the opposition in the upper house. In recent years, around ten ordinances have been passed annually, though at the peak of their use, over 30 were passed in a single year.[87]Ordinances can vary widely on their topic; recent examples of ordinances include items as varied as modifications to land owner rights, emergency responses to the COVID-19 pandemic, and changes to banking regulations.[87][88]

Federalism

The first article of the Constitution declares that India is a "Union of States".[89]Under the Constitution, the States retain key powers for themselves and have a strong influence over the national government via the Rajya Sabha. However, the Constitution does provide key limits on their powers and gives final say in many cases to the national government.

State powers in the Constitution

Rajya Sabha

At the Union level, the States are represented in the Rajya Sabha or Council of States. The Fourth Schedule of the Constitution lays out the number of seats that each State controls in the Council of States, and they are based roughly on each State's population.[90]The members of each state legislature elect and appoint these representatives in the Council of States.[91]On most topics the Rajya Sabha is coequal with the lower house or Lok Sabha, and its consent is required for a bill to become a law.[92]Additionally, as one of the Houses of Parliament, any amendment to the Constitution requires a two-thirds majority in the Rajya Sabha to go into effect.[93]These provisions allow the States significant impact on national politics through their representation in the "federal chamber".[90]

State List

The Constitution provides the States with a long list of powers exclusive to their jurisdiction.[90]Generally only State Legislatures are capable of passing laws implementing these powers; the Union government is prohibited from doing so. These powers are contained in the second list of the Seventh Schedule of the Constitution, known as the State List. The areas on the State List are wide-ranging and include topics like public health and order and a variety of taxes. The State List grants the states control over the police, healthcare, agriculture, elections, and more.[94]

Powers can only be permanently removed from the State List via a constitutional amendment approved by a majority of the states. The Rajya Sabha, as the representative of the States, can temporarily remove an item from the State List so the Union parliament can legislate on it. This requires a two-thirds vote and lasts for a renewable one-year period.[90]

Amendments

In addition to exerting influence over the amendment process via the Rajya Sabha, the States are sometimes involved in the amendment process. This special,entrenchedprocess is triggered when an amendment to the Constitution specifically concerns the States by modifying the legislature or the powers reserved to the states in the Seventh Schedule. When this occurs, an amendment must be ratified by a majority of state legislatures for the amendment to go into effect.[93]

Limitations on state powers

Union and Concurrent Lists

While the State List mentioned above provides powers for the States, there are two other lists in the Seventh Schedule that generally weaken them. These are the Union and Concurrent lists. The Union List is the counterpart to the State List, containing the areas of exclusive jurisdiction of the Union government, where the states are prohibited from legislating.[95]Items on the Union List include the national defense, international relations, immigration, banking, and interstate commerce.[94]

The final list is the Concurrent List which contains the topics on whichboththe Union and State-level governments may legislate on. These topics include courts and criminal law, unions, social security, and education.[94]In general, when the Union and State laws on a Concurrent List item conflict, the Union-level laws prevail. The only way for the State-level law to override the national one is with the consent of the President, acting on the advice of the Prime Minister.[96]

Additionally, any powers not on any of the three lists are reserved for the Union government and not for the states.[97]

Appointment of governors

The Governor of each State is given the executive power of the respective State by the Constitution.[98]These Governors are appointed directly by the President of the central government. Because the Prime Minister acts via the President, the Prime Minister is the one who chooses the Governors in practice.[99]Once appointed, a Governor serves for a five-year term or can be replaced by the President at any time, if asked to do so by the Prime Minister.[100]Because the Union government can remove a Governor at any time, it is possible that Governors may act in a way the Union Government wants, to the detriment of their state, so that they can maintain their office. This has become a larger issue as the State Legislatures are often controlled by different parties than that of the Union Prime Minister, unlike the early years of the constitution.[101]For example, Governors have used stalling tactics to delay giving their assent to legislation that the Union Government disapproves of.[102]

In general the influence of the Union on State politics via the Governor is limited, however, by the fact that the Governor must listen to the advice of the Chief Minister of the State who needs to command a majority in the State Legislature.[103]There are key areas where the Governor does not need to heed the advice of the Chief Minister. For example, the Governor can send a bill to president for consideration instead of signing it into law.[104]

Creation of states

Perhaps the most direct power over the States is the Union's ability to unilaterally create new states out of territories or existing states and to modify and diminish the boundaries of existing states.[105]To do so, Parliament must pass a simple law with no supermajority requirements. The States involved do not have a say on the outcome but the State Legislature must be asked to comment.[106]The most recent state to be created wasTelanganain 2014.[107]More recently,Ladakhwas created as a new Union Territory after being split off fromJammu and Kashmirin 2019, andDaman and DiuandDadra and Nagar Haveliwere combined into asingle Union Territoryin 2020.[108][109]The former was particularly opposed by some e.g. Arundhati Roy. In her opinion, Jammu and Kashmir was a full state, and the legislation creating Ladakh stripped the area of its status as a state and downgraded it to a Union Territory, allowing the Union Government to directly control it. This required no input from Jammu and Kashmir.[110]

Federalism and the courts

While the states have separate legislative and executive branches, they share the judiciary with the Union government. This is different from other federal court systems, such as the United States, where state courts mainly apply state law and federal courts mainly apply federal law.[111]Under the Indian constitution, the High Courts of the States are directly constituted by the national constitution. The constitution also allows states to set up lower courts under and controlled by the state's High Court.[112][113]Cases heard at or appealed to the High Courts can be furter appealed to theSupreme Court of Indiain some cases.[114]All cases, whether dealing with federal or state laws, move up the same judicial hierarchy, creating a system sometimes termed integrated federalism.[111]

International law

The Constitution includes treaty making as part of the executive power given to the President.[115]Because the President must act in accordance with the advice of the Council of Ministers, the Prime Minister is the chief party responsible for making international treaties in the Constitution. Because the legislative power rests with Parliament, the President's signature on an international agreement does not bring it into effect domestically or enable courts to enforce its provisions. Article 253 of the Constitution bestows this power on Parliament, enabling it to make laws necessary for implementing international agreements and treaties.[116]These provisions indicate that the Constitution of India isdualist,that is, treaty law only takes effect when a domestic law passed using the normal processes incorporates it into domestic law.[117]

Recent Supreme Court decisions have begun to change this convention, incorporating aspects of international law without enabling legislation from parliament.[118]For example, inGramophone Company of India Ltd. v Birendra Bahadur Pandey,the Court held that "the rules of international law are incorporated into national law and considered to be part of the national law, unless they are in conflict with an Act of Parliament."[119]In essence, this implies that international law applies domesticallyunlessparliament says it does not.[117]This decision moves the Indian Constitution to a more hybrid regime, but not to a fullymonistone.

Flexibility

According toGranville Austin,"The Indian constitution is first and foremost a social document, and is aided by its Parts III & IV (Fundamental Rights & Directive Principles of State Policy, respectively) acting together, as its chief instruments and its conscience, in realising the goals set by it for all the people."[h][120]The constitution has deliberately been worded in generalities (not in vague terms) to ensure its flexibility.[121]John Marshall,the fourthchief justice of the United States,said that a constitution's "great outlines should be marked, its important objects designated, and the minor ingredients which compose those objects be deduced from the nature of the objects themselves."[122]A document "intended to endure for ages to come",[123]it must be interpreted not only based on the intention and understanding of its framers, but in the existing social and political context.

The "right to life"guaranteed under Article 21[i]has been expanded to include a number of human rights, including:[4]

- the right to a speedy trial;[124]

- the right to water;[125]

- the right to earn a livelihood,

- theright to health,and

- the right to education.[126]

At the conclusion of his book,Making of India's Constitution,retired Supreme Court JusticeHans Raj Khannawrote:

If the Indian constitution is our heritage bequeathed to us by our founding fathers, no less are we, the people of India, the trustees and custodians of the values which pulsate within its provisions! A constitution is not a parchment of paper, it is a way of life and has to be lived up to. Eternal vigilance is the price of liberty and in the final analysis, its only keepers are the people.[127]

Translations into Indian languages

The Constitution of India is translated into only a few of the22 scheduled languages of the Indian Republic.

Hindi translation

TheHinditranslation of the Indian Constitution is notably the first translation among Indian languages. This task was undertaken byRaghu Vira,a distinguished linguist, scholar, politician, and member of the Constituent Assembly.

In 1948, nearly two years after the formation of the Constituent Assembly, Rajendra Prasad entrusted Raghu Vira and his team to translate the English text of the Constitution into Hindi.[128]Raghu Vira, using Sanskrit as a common base akin to the role of Latin in European languages, applied the rules ofsandhi(joining),samasa(compounding),upasarga(prefix), andpratyaya(suffix) to develop several new terms for scientific and parliamentary use. The terminology was subsequently approved by an All India Committee of Linguistic Experts, representing thirteen languages: Sanskrit, Tamil, Telugu, Malayalam, Odia (then spelled as Oriya), Assamese, Gujarati, Hindi, Kannada, Malayalam, Marathi, Punjabi, Kashmiri, and Urdu. The vocabulary developed for Hindi later served as a base for translating the constitution into several other Indic languages.[129]

Bengali translation

The Constitution of India was first translated from English intoBengali languageand published in 1983, asভারতের সংবিধান(romanised:"Bharoter Songbidhan") inKolkata,through the collective efforts of theGovernment of West Bengaland theUnion Government of India.Its second edition was published in 1987, and third in 2022. It contains up to the One hundred and fifth Amendment of the Constitution.[130]

Meitei translation

The Constitution of India was first translated from English intoMeitei language(officially known asManipuri language) and published on 3 January 2019, asভারতকী সংবিধান,inImphal,through the collective efforts of theGovernment of Manipurand theUnion Government of India.It was written inBengali script.It contains up to the Ninety-fifth Amendment of the Constitution.[131]The translation project was started in 2016 by the Directorate of Printing & Stationery of theGovernment of Manipur.[132]

On 19 November 2023,Nongthombam Biren Singh,the thenChief Minister of Manipurdeclared that it will be transliterated intoMeetei Mayek(Meiteifor 'Meitei script') in digital edition.[133]

On 26 November 2023,Nongthombam Biren Singh,the thenChief Ministerof theGovernment of Manipur,officially released thediglot editionof the Constitution of India, in theMeetei Mayek(Meiteifor 'Meitei writing system') inManipuri languageand English,[134][135][136]at the Cabinet hall of the CM Secretariat inImphal,[137]as part of theConstitution Day celebrations (National Law Day)of theRepublic of India,[138]containing up to the105th Amendment of the Constitution,[139][134]for the first time in its history.[139]It was made to be available in all educational institutions, government offices, and public libraries across theManipur state.[140]

Odia translation

The Constitution of India was first translated from English intoOdia languageand published on 1 April 1981, asଭାରତର ସମ୍ବିଧାନ(romanised:"Bharater Sangbidhana") inBhubaneswar,through the collective efforts of theGovernment of Odishaand theUnion Government of India.[141]

Sanskrit translation

The Constitution of India was first translated from English intoSanskrit languageand published on 1 April 1985, asभारतस्य संविधानम्(romanised:"Bhartasya Samvidhanam") inNew Delhi.[142]

Tamil translation

The 4th edition of Constitution of India inTamil languagewas published in 2021, asஇந்திய அரசியலமைப்பு(romanised:"Intiya araciyalamaippu") inChennai,through the collective efforts of theGovernment of Tamil Naduand theUnion Government of India.It contains up to the One hundred and fifth Amendment of the Constitution.[143]

See also

- Constitution Day (India)

- Constitutional economics

- Constitutionalism

- History of democracy

- List of national constitutions

- Loiyumpa Silyel

- Magna Carta

- Rule according to higher law

- Uniform Civil Code

- B. N. Rau

Explanatory notes

- ^Although the last article of the 1974 Constitution of Yugoslavia was Article 406, the Yugoslav constitution contained about 56,000 words in its English translation

- ^Although the last article of the constitution is Article 395, the total number in March 2013 was 465. New articles added through amendments have been inserted in the relevant location of the original constitution. To not disturb the original numbering, new articles are inserted alphanumerically; Article 21A, pertaining to the right to education, was inserted by the 86th Amendment Act.

- ^The Constitution was in 22 Parts originally. Part VII & IX (older) was repealed in 1956, whereas newly added Part IVA, IXA, IXB & XIVA by Amendments to the Constitution in different times (lastly added IXB by the 97th Amendment).

- ^By the 73rd and 74th Amendments, the lists of administrative subjects of Panchayat raj & Municipality were included in the Constitution as Schedules 11 and 12 respectively in the year 1993.

- ^Scheduled Areas are autonomous areas within a state, administered federally and usually mainly populated by a Scheduled Tribe.

- ^Scheduled Tribes are groups ofindigenous people,identified in the Constitution, who are strugglingsocioeconomically

- ^Originally Articles mentioned here were immune from judicial review on the ground that they violated fundamental rights, but in a landmark judgement in 2007, the Supreme Court of India held in I.R. Coelho v. State of Tamil Nadu and others that laws included in the 9th schedule can be subject to judicial review if they violated the fundamental rights guaranteed under Article 14, 15, 19, 21 or the basic structure of the Constitution[ambiguous]– I.R. Coelho (dead) by L.Rs. v. State of Tamil Nadu and others(2007) 2 S.C.C. 1

- ^These lines byGranville Austinfrom his bookThe Indian Constitution: Cornerstone of a Nationat p. 50, have been authoritatively quoted many times

- ^Art. 21 – "No person shall be deprived of his life or personal liberty except according to procedure established by law"

Citations

- ^abc"Doctrine of Basic Structure – Constitutional Law".www.legalserviceindia.com.Archivedfrom the original on 21 March 2016.Retrieved26 January2016.

- ^Original edition with original artwork - The Constitution of India.New Delhi: Government of India. 26 November 1949.Archivedfrom the original on 22 March 2019.Retrieved22 March2019.

- ^"Preface, The constitution of India"(PDF).Government of India.Archived(PDF)from the original on 31 March 2015.Retrieved5 February2015.

- ^abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyKrithika, R. (21 January 2016)."Celebrate the supreme law".The Hindu.ISSN0971-751X.OCLC13119119.Archivedfrom the original on 21 December 2016.Retrieved24 July2018.

- ^abPylee, Moolamattom Varkey (1994).India's Constitution(5th rev. and enl. ed.).New Delhi:R. Chand & Company. p. 3.ISBN978-8121904032.OCLC35022507.

- ^abNix, Elizabeth (9 August 2016)."Which country has the world's shortest written constitution?".History.A&E Networks.Archivedfrom the original on 24 July 2018.Retrieved24 July2018.

- ^"Introduction to Constitution of India".Ministry of Law and Justice of India. 29 July 2008.Archivedfrom the original on 22 October 2014.Retrieved14 October2008.

- ^Swaminathan, Shivprasad (26 January 2013)."India's benign constitutional revolution".The Hindu: Opinion.Archivedfrom the original on 1 March 2013.Retrieved18 February2013.

- ^Das, Hari (2002).Political System of India(Reprint ed.).New Delhi:Anmol Publications. p. 120.ISBN978-8174884961.

- ^"Aruna Roy & Ors. v. Union of India & Ors"(PDF).Supreme Court of India. 12 September 2002. p. 18/30.Archived(PDF)from the original on 7 May 2016.Retrieved11 November2015.

- ^"Preamble of the Constitution of India"(PDF).Ministry of Law & Justice. Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 9 October 2017.Retrieved29 March2012.

- ^Malhotra, G. C. (September 2000)."The Parliament Estate"(PDF).The Journal of Parliamentary Information.XLVI(3): 406.Archived(PDF)from the original on 3 October 2022.Retrieved17 October2022.

- ^Elster, Jon; Gargarella, Roberto; Naresh, Vatsal; Rasch, Bjørn Erik (2018).Constituent Assemblies.Cambridge University Press. p. 64.ISBN978-1-108-42752-4.

Nevertheless, partition increased the dominance of the Congress Party in the constituent assembly, which in turn made it easier for its leadership to incorporate in the constitution elements of its vision of Indian unity. This vision was based on a decades-long period of Congress-led consultation concerning the future independent constitution. More importantly, it rested on a detailed draft constitution adopted in 1928 by the All Parties Conference that met in Lucknow. The draft, known as the "Nehru Report," was written by a seven-member committee, chaired by Motilal Nehru.... The committee was appointed during the May 1928 meeting of the All Parties Conference, which included representatives of all the major political organizations in India, including the All-India Hindu Mahasabha, the All-India Muslim League, the All-India Liberal Federation, the States' Peoples Conference, The Central Khalifat Committee, the All-India Conference of Indian Christians, and others.

- ^Menon, V.P. (15 September 1955).The story of the integration of the India states.Bangalore: Longman Greens and Co.

- ^"Commencement".Archivedfrom the original on 20 February 2015.Retrieved20 February2015.

- ^abcdefghijklmnYellosa, Jetling (26 November 2015)."Making of Indian Constitution".The Hans India.Archivedfrom the original on 24 July 2018.Retrieved24 July2018.

- ^abcd"The Constituent Assembly Debates (Proceedings) (9 December 1946 to 24 January 1950)".The Parliament of India Archive. Archived fromthe originalon 29 September 2007.Retrieved22 February2008.

- ^Raja, D. (14 June 2016)."Denying Ambedkar his due".Archivedfrom the original on 31 March 2019.Retrieved6 April2019.

- ^"Constituent Assembly of India Debates".164.100.47.194.Archivedfrom the original on 7 January 2019.Retrieved6 April2019.

- ^"Dr B.R. Ambedkar concluding speech in constituent assembly on November 25, 1949"(PDF).Archived(PDF)from the original on 2 August 2020.Retrieved4 January2020.

- ^"First Day in the Constituent Assembly".Parliament of India. Archived fromthe originalon 11 May 2011.Retrieved12 May2014.

- ^abcd"Evolution of the Indian Constitution"(PDF).Surendranath Evening College.Surendranath Evening College.Retrieved28 September2024.

- ^abcdef"Making of the Indian Constitution".Employment News.25 January 2020.Archivedfrom the original on 14 July 2021.Retrieved14 July2021.

- ^"Civics and Polity: The Making of Indian Constitution".Leverage Edu.Leverage Edu.Retrieved28 September2024.

- ^"History Of Indian Tricolor".Archivedfrom the original on 7 March 2023.Retrieved10 September2023.

- ^"On Republic Day, Gautam Khaitan remembers great-grandfather, an architect of Indian Constitution".ANI News.Archivedfrom the original on 16 April 2023.Retrieved16 April2023.

- ^AK, Aditya (26 January 2018)."Republic Day: The Lawyers who helped draft the Constitution of India".Bar and Bench - Indian Legal news.Archivedfrom the original on 17 September 2023.Retrieved16 April2023.

- ^"The Making and Evolution of Indian Constitution".Archivedfrom the original on 17 September 2023.Retrieved10 September2023.

- ^"CONSTITUTION OF INDIA".Archivedfrom the original on 14 April 2023.Retrieved10 September2023.

- ^"Interesting Facts About the Indian Constitution".BPAC.Bangalore Political Action Committee.Retrieved28 September2024.

- ^"G. V. Mavalankar".Constitution of India.Constitution of India Website.Retrieved28 September2024.

- ^abcdefghijklmnoDhavan, Rajeev (26 November 2015)."Document for all ages: Why Constitution is our greatest achievement".Hindustan Times.OCLC231696742.Archivedfrom the original on 24 July 2018.Retrieved24 July2018.

- ^abPatnaik, Biswaraj (26 January 2017)."BN Rau: The Forgotten Architect of Indian Constitution".The Pioneer.Bhubaneswar:Chandan Mitra.Archivedfrom the original on 24 July 2018.Retrieved24 July2018.

- ^Shourie, Arun."The Manu of Our Times?".The Arun Shourie Site.Archived fromthe originalon 20 February 2012.Retrieved13 June2013.

- ^abcde"Celebrating Constitution Day".The Hindu.26 November 2015.ISSN0971-751X.OCLC13119119.Archivedfrom the original on 27 June 2019.Retrieved26 July2018.

- ^"CONSTITUENT ASSEMBLY OF INDIA DEBATES"(PDF).Archived(PDF)from the original on 1 August 2020.Retrieved4 January2020.

- ^ab"Some Facts of Constituent Assembly".Parliament of India.National Informatics Centre. Archived fromthe originalon 11 May 2011.Retrieved14 April2011.

On 29 August 1947, the Constituent Assembly set up a Drafting Committee under the Chairmanship of B. R. Ambedkar to prepare a Draft Constitution for India

- ^Sudheesh, Raghul (26 November 2011)."On National Law Day, saluting two remarkable judges".First Post.Archived fromthe originalon 30 November 2015.

- ^"PM Modi greets people on Constitution Day".DNA India.26 November 2015. Archived fromthe originalon 27 November 2015.

- ^"November 26 to be observed as Constitution Day: Facts on the Constitution of India".India Today.12 October 2015.Archivedfrom the original on 14 November 2015.Retrieved20 November2015.

- ^"Original unamended constitution of India, January, 1950".Archivedfrom the original on 17 April 2014.Retrieved17 April2014.

- ^"The Constitution (Amendment) Acts".India Code Information System.Ministry of Law, Government of India.Archivedfrom the original on 27 April 2008.Retrieved9 December2013.

- ^abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwx"Constitution Day: Borrowed features in the Indian Constitution from other countries".India Today.Archivedfrom the original on 7 March 2021.Retrieved12 July2021.

- ^Bahl, Raghav(27 November 2015)."How India Borrowed From the US Constitution to Draft its Own".The Quint.Archivedfrom the original on 24 July 2018.Retrieved24 July2018.

- ^Sridhar, Madabhushi."Evolution and Philosophy behind the Indian Constitution (page 22)"(PDF).Dr.Marri Channa Reddy Human Resource Development Institute (Institute of Administration), Hyderabad. Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 16 June 2015.Retrieved22 October2015.

- ^Bélanger, Claude."Quebec History".faculty.marianopolis.edu.Archivedfrom the original on 28 October 2020.Retrieved27 June2020.

- ^Lockette, Tim (18 November 2012)."Is the Alabama Constitution the longest constitution in the world?Truth Rating: 4 out of 5".The Anniston Star.Josephine Ayers.Archivedfrom the original on 17 May 2019.Retrieved24 July2018.

- ^"Constitution of india".Ministry of Law and Justice, Govt. of India.Archived fromthe originalon 25 March 2016.Retrieved4 July2010.

- ^Baruah, Aparijita (2007).Preamble of the Constitution of India: An Insight and Comparison with Other Constitutions.New Delhi: Deep & Deep. p. 177.ISBN978-81-7629-996-1.Archivedfrom the original on 17 September 2023.Retrieved12 November2015.

- ^Chishti, Seema; Anand, Utkarsh (30 January 2015)."Legal experts say debating Preamble of Constitution pointless, needless".The Indian Express.Archivedfrom the original on 27 October 2015.Retrieved12 November2015.

- ^"Forty-Second Amendment to the Constitution".Ministry of Law and Justice of India. 28 August 1976.Archivedfrom the original on 28 March 2015.Retrieved14 October2008.

- ^Part I

- ^"The Constitution (Ninety Seventh Amendment)"(PDF).Archived(PDF)from the original on 22 May 2012.Retrieved17 November2013.

- ^abMenon, N.R. Madhava (26 September 2004)."Parliament and the Judiciary".The Hindu.Archived fromthe originalon 16 November 2016.Retrieved21 November2015.

- ^Laxmikanth, M (2013). "3".Indian Polity(4th ed.). McGraw Hill Education. p. 3.2.ISBN978-1-25-906412-8.

- ^Krishnakumar, R."Article 356 should be abolished".Frontline.Vol. 15, no. 14.Archivedfrom the original on 30 March 2016.Retrieved9 November2015.

- ^Rajendra Prasad, R.J."Bommai verdict has checked misuse of Article 356".Frontline.Vol. 15, no. 14.Archivedfrom the original on 20 December 2019.Retrieved9 November2015.

- ^Swami, Praveen."Protecting secularism and federal fair play".Frontline.Vol. 14, no. 22.Archivedfrom the original on 19 February 2014.Retrieved9 November2015.

- ^"Pages 311 & 312 of original judgement: A. K. Roy, Etc vs Union Of India And Anr on 28 December, 1981".Archivedfrom the original on 26 August 2014.Retrieved23 August2014.

- ^Krishnamurthi, Vivek (2009)."Colonial Cousins: Explaining India and Canada's Unwritten Constitutional Principles"(PDF).Yale Journal of International Law.34(1): 219. Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 4 March 2016.

- ^Dhamija, Ashok (2007).Need to Amend a Constitution and Doctrine of Basic Features.Wadhwa and Company. p. 568.ISBN9788180382536.Archivedfrom the original on 17 September 2023.Retrieved17 June2014.

- ^Jacobsohn, Gary J. (2010).Constitutional Identity.Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. p.52.ISBN9780674047662.

- ^abDalal, Milan (2008)."India's New Constitutionalism: Two Cases That Have Reshaped Indian Law".Boston College International Comparative Law Review.31(2): 258–260.Archivedfrom the original on 18 October 2015.Retrieved5 March2015.

- ^Mehta, Pratap Bhanu (2002). Hasan, Zoya; Sridharan, E.; Sudarshan, R. (eds.).Article – The Inner Conflict of Constitutionalism: Judicial Review and the 'Basic Structure' (Book – India's Kiving Constitution: Ideas, Practices, Controversies)((2006)Second Impression (2002)First ed.). Delhi: Permanent Black. p. 187.ISBN81-7824-087-4.Archivedfrom the original on 17 September 2023.Retrieved9 November2015.

- ^Bhattacharyya, Bishwajit."Supreme Court Shows Govt Its LoC".the day after.No. 1–15 Nov 2015. Archived fromthe originalon 5 May 2016.Retrieved10 November2015.

- ^"A Consultation Paper on the Financial Autonomy of the Indian Judiciary".National Commission to Review the Working of the Constitution. 26 September 2001. Archived fromthe originalon 4 March 2016.Retrieved5 November2015.

- ^Chakrabarty, Bidyut (2008).Indian Politics and Society Since Independence: Events, Processes and Ideology(First ed.). Oxon(UK), New York (US): Routledge. p. 103.ISBN978-0-415-40867-7.Archivedfrom the original on 17 September 2023.Retrieved5 November2015.

- ^Sorabjee, Soli J. (1 November 2015)."A step in the Wrong Direction".The Week.Archivedfrom the original on 13 November 2015.Retrieved12 November2015.

- ^Venkatesan, V. (10–23 March 2012)."Three doctrines".Frontline.Vol. 29, no. 5.ISSN0970-1710.Archivedfrom the original on 13 June 2014.Retrieved26 July2018.

- ^Jain, Mahabir Prashad (2010).Indian Constitutional Law(6th ed.).Gurgaon:LexisNexis Butterworths Wadhwa Nagpur. p. 921.ISBN978-81-8038-621-3.OCLC650215045.

- ^Lectures By Professor Parmanad Singh, Jindal Global Law School.

- ^Jacobsohn, Gary (2010).Constitutional Identity.Cambridge, Massachusetts:Harvard University Press.pp.57.ISBN978-0674047662.OCLC939085793.

- ^Chandrachud, Chintan (6 June 2015)."India's deceptive Constitution".The Hindu.ISSN0971-751X.OCLC13119119.Archivedfrom the original on 25 June 2018.Retrieved26 July2018.

- ^"The Hindu: Front Page: President appoints Manmohan Prime Minister".3 June 2012. Archived fromthe originalon 3 June 2012.Retrieved17 October2021.

- ^ab"Part V, Article 75".Archivedfrom the original on 13 September 2006.

- ^"Parliament of India, Lok Sabha".164.100.47.194.Archivedfrom the original on 21 January 2022.Retrieved17 October2021.

- ^"Part V, Article 53".Archivedfrom the original on 13 September 2006.

- ^ab"Part V, Article 74".Archivedfrom the original on 13 September 2006.

- ^ab"What is India's president actually for?".BBC News.2 August 2017.Archivedfrom the original on 2 June 2018.Retrieved17 October2021.

- ^"Parts of the Indian Constitution that were 'inspired by' others".Deccan Herald.25 January 2021.Archivedfrom the original on 11 January 2022.Retrieved11 January2022.

- ^Go, Julian (March 2002). "Modeling the State".Southeast Asian Studies.39(4): 558–583.

- ^"Part V, Article 55".Archivedfrom the original on 13 September 2006.

- ^"Part V, Article 111".Archivedfrom the original on 13 September 2006.

- ^Das Gupta, Surajeet; Badhwar, Inderjit (15 May 1987)."Under the Constitution, does the President have the right to remove the Prime Minister?".India Today.Archivedfrom the original on 6 August 2020.Retrieved18 October2021.

- ^"Part V, Article 123".Archivedfrom the original on 13 September 2006.

- ^"Repeated promulgation of ordinances because a bill is held up in the Rajya Sabha is a violation of constitutional principles".Times of India Blog.27 September 2016.Archivedfrom the original on 19 February 2022.Retrieved18 October2021.

- ^abAney, Madhav S.; Dam, Shubhankar (1 October 2021)."Decree Power in Parliamentary Systems: Theory and Evidence from India".The Journal of Politics.83(4): 1432–1449.doi:10.1086/715060.ISSN0022-3816.S2CID235567253.Archivedfrom the original on 11 January 2022.Retrieved11 January2022.

- ^"The ordinance raj of the Bharatiya Janata Party".Hindustan Times.11 September 2020.Archivedfrom the original on 11 January 2022.Retrieved11 January2022.

- ^"Part I, Article 1".Archivedfrom the original on 13 September 2006.

- ^abcd"Rajya Sabha".rajyasabha.nic.in.Archivedfrom the original on 26 January 2022.Retrieved19 October2021.

- ^"Part V, Article 80".Archivedfrom the original on 13 September 2006.

- ^"Part V, Article 107".Archivedfrom the original on 13 September 2006.

- ^ab"Part XX, Article 368".Archivedfrom the original on 13 September 2006.

- ^abc"Constitution of India".Archivedfrom the original on 22 June 2018.

- ^"Part XI, Article 246".Archivedfrom the original on 13 September 2006.

- ^"Congress mulls using Article 254(2) to bypass farm laws: All you need to know about the rarely-used provision".Firstpost.29 September 2020.Archivedfrom the original on 7 December 2021.Retrieved19 October2021.

- ^"Part XI, Article 248".Archivedfrom the original on 13 September 2006.

- ^"Part VI, Article 154".Archivedfrom the original on 13 September 2006.

- ^"Part VI, Article 155".Archivedfrom the original on 13 September 2006.

- ^"Part VI, Article 156".Archivedfrom the original on 13 September 2006.

- ^Reddy, Jeevan (11 May 2001)."The Institution of Governor Under the Constitution"(PDF).Archived(PDF)from the original on 23 November 2018.

- ^Chatterji, Rakhahari (6 June 2020)."Recurring Controversy About Governor's Role in State Politics"(PDF).Archived(PDF)from the original on 23 November 2018.

- ^"Part VI, Article 163".Archivedfrom the original on 13 September 2006.

- ^"Part VI".Archivedfrom the original on 13 September 2006.

- ^"Part I, Article 2".Archivedfrom the original on 13 September 2006.

- ^"Part I, Article 3".Archivedfrom the original on 13 September 2006.

- ^"New State Formation"(PDF).Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 27 March 2014.Retrieved11 January2022.

- ^"Introduction | The Administration of Union Territory of Ladakh | India".Archivedfrom the original on 18 January 2022.Retrieved11 January2022.

- ^"About UT Administration | UT of Dadra and Nagar Haveli and Daman and Diu | India".Archivedfrom the original on 11 January 2022.Retrieved11 January2022.

- ^Roy, Arundhati (15 August 2019)."Opinion | The Silence Is the Loudest Sound".The New York Times.ISSN0362-4331.Archivedfrom the original on 27 October 2021.Retrieved11 January2022.

- ^abDam, Sukumar (1964)."Judiciary in India".The Indian Journal of Political Science.25(3/4): 276–281.ISSN0019-5510.JSTOR41854040.Archivedfrom the original on 11 January 2022.Retrieved11 January2022.

- ^"Part VI, Article 214".Archivedfrom the original on 13 September 2006.

- ^"Part VI, Article 235".Archivedfrom the original on 13 September 2006.

- ^"Part V, Article 133-134".Archivedfrom the original on 13 September 2006.

- ^"Part V, Article 73".Archivedfrom the original on 13 September 2006.

- ^"Part XI, Article 253".Archivedfrom the original on 13 September 2006.

- ^abChandra, Aparna (1 June 2017)."India and international law: formal dualism, functional monism".Indian Journal of International Law.57(1): 25–45.doi:10.1007/s40901-017-0069-0.ISSN2199-7411.S2CID148598173.Archivedfrom the original on 17 September 2023.Retrieved11 January2022.

- ^"Are the Indian Courts Still Following the Constitutional Principle of Dualism? Not Quite So".The RMLNLU Law Review Blog.31 March 2020.Archivedfrom the original on 21 October 2021.Retrieved18 October2021.

- ^"Gramophone Company of India Ltd. v Birendra Bahadur Pandey".Archivedfrom the original on 18 March 2009.

- ^Raghavan, Vikram (2010)."The biographer of the Indian constitution".Seminar.Archivedfrom the original on 19 September 2015.Retrieved13 November2015.

- ^Dharmadhikari, D. M."Principle of Constitutional Interpretation: Some Reflections".(2004) 4 SCC (Jour) 1.Archivedfrom the original on 28 January 2016.Retrieved6 November2015.

- ^McCulloch v. Maryland,17 U.S. (4 Wheaton) 316, 407 (U.S. Supreme Court1819),Text.

- ^McCulloch v. Maryland,17 U.S. (4 Wheaton) 316, 415 (U.S. Supreme Court1819),Text.

- ^Gaur, K. D. (2002).Article – Law and the Poor: Some Recent Developments in India (Book – Criminal Law and Criminology).New Delhi: Deep & Deep. p. 564.ISBN81-7629-410-1.Archivedfrom the original on 17 September 2023.Retrieved9 November2015.

- ^Narain, Vrinda. "Water as a Fundamental Right: A Perspective from India".Vermont Law Review.34(917): 920.

- ^Khosla, Madhav (2011)."Making social rights conditional: Lessons from India".International Journal of Constitutional Law.8(4): 761.doi:10.1093/icon/mor005.

- ^Khanna, Hans Raj(2008).Making of India's constitution(2nd ed.).Lucknow:Eastern Book Co (published 1 January 2008).ISBN978-81-7012-108-4.OCLC294942170.

- ^"Constituent Assembly Discussions on July 30, 1949".indiankanoon.org.

- ^"A Tragedy That Struck Sanskrit, Hindi, Hinduism, And Cultural Legacy of India".swargvibha.freevar.com.

- ^"Constitution of India in Bengali version"(PDF).legislative.gov.in(in Bengali). Government of India.

- ^"The Constitution of India in Manipuri"(PDF).legislative.gov.in(in Manipuri). Government of India.

- ^"Manipur Govt to Publish Indian Constitution in Manipuri".20 July 2016.Retrieved19 November2023.

- ^—"'Indian Constitution in Meetei Mayek'".Imphal Free Press.Retrieved19 November2023.

—"Constitution to be published in Meetei Mayek script: Manipur CM Biren Singh".The Times of India.18 November 2023.ISSN0971-8257.Retrieved19 November2023.

—"Digital Edition Of Constitution In Meetei Mayek Script Soon: Manipur Chief Minister".NDTV.com.Retrieved19 November2023.

—"Manipur: Constitution of India will be published in Meetei Mayek script, announces CM N Biren Singh".India Today NE.18 November 2023.Retrieved19 November2023.

—"Constitution Will Be Published In Meetei Mayek Script, Announces Manipur CM Biren Singh".TimesNow.18 November 2023.Retrieved19 November2023.

—"Manipur: Constitution to be soon published in Meetei-Mayek script".Northeast Live.19 November 2023.Retrieved19 November2023. - ^ab"Manipur Chief Minister releases diglot edition of Constitution in Meetei Mayek".India Today.26 November 2023.Retrieved26 November2023.

- ^Biren Singh Launches Digital Edition Of Constitution In Manipuri Language,retrieved26 November2023

- ^"Manipur CM N Biren Singh Launches Diglot Edition of Constitution in Meitei Mayek Script".26 November 2023.Retrieved26 November2023.

- ^"Manipur: Indian Constitution published in Meetei-Mayek script, CM N Biren Singh releases Diglot edition".India Today NE.26 November 2023.Retrieved26 November2023.

- ^"Constitution Day 2023: Manipur CM Biren Singh Launches Diglot Edition of Indian Constitution In Regional Language".www.india.com.Retrieved26 November2023.

- ^ab"Manipur CM Biren Releases Indian Constitution In Manipuri Language In Imphal".26 November 2023.Retrieved26 November2023.

- ^"Constitution Day 2023: Manipur CM Biren Singh Launches Diglot Edition of Indian Constitution In Regional Language".www.india.com.Retrieved26 November2023.

- ^"The Constitution of India in Oriya version"(PDF).legislative.gov.in(in Odia). Government of India.

- ^"The Constitution of India in Sanskrit"(PDF).legislative.gov.in(in Sanskrit). Government of India.

- ^"Constitution of India in Tamil | Legislative Department | India".Retrieved19 November2023.

General bibliography

- Austin, Granville(1999).The Indian Constitution: Cornerstone of a Nation(2nd ed.). Oxford University Press.ISBN978-01-9564-959-8.

- —— (2003).Working a Democratic Constitution: A History of the Indian Experience(2nd ed.). Oxford University Press.ISBN978-01-9565-610-7.

- Baruah, Aparajita (2007).Preamble of the Constitution of India: An Insight & Comparison.Eastern Book Co.ISBN978-81-7629-996-1.

- Basu, Durga Das (1965).Commentary on the constitution of India: (being a comparative treatise on the universal principles of justice and constitutional government with special reference to the organic instrument of India).Vol. 1–2. S. C. Sarkar & Sons (Private) Ltd.

- —— (1981).Shorter Constitution of India.Prentice-Hall of India.ISBN978-0-87692-200-2.

- —— (1984).Introduction to the Constitution of India(10th ed.). South Asia Books.ISBN0-8364-1097-1.

- —— (2002).Political System of India.Anmol Publications.ISBN81-7488-690-7.

- Dash, Shreeram Chandra (1968).The Constitution of India; a Comparative Study.Chaitanya Pub. House.

- Dhamija, Dr. Ashok (2007).Need to Amend a Constitution and Doctrine of Basic Features.Wadhwa and Company.ISBN9788180382536.

- Ghosh, Pratap Kumar (1966).The Constitution of India: How it Has Been Framed.World Press.

- Jayapalan, N. (1998).Constitutional History of India.Atlantic Publishers & Distributors.ISBN81-7156-761-4.

- Khanna, Hans Raj(1981).Making of India's Constitution.Eastern Book Co.ISBN978-81-7012-108-4.

- Khanna, Justice H. R.(2015) [2008].Making of India's Constitution(reprint) (2nd ed.). Eastern Book Company.ISBN978-81-7012-188-6.

- Rahulrai, Durga Das (1984).Introduction to the Constitution of India(10th ed.). South Asia Books.ISBN0-8364-1097-1.

- Pylee, M.V. (1997).India's Constitution.S. Chand & Co.ISBN81-219-0403-X.

- —— (2004).Constitutional Government in India.S. Chand & Co.ISBN81-219-2203-8.

- Sen, Sarbani (2007).The Constitution of India: Popular Sovereignty and Democratic Transformations.Oxford University Press.ISBN978-0-19-568649-4.

- Sharma, Dinesh; Singh, Jaya; Maganathan, R.; et al. (2002).Indian Constitution at Work.Political Science, Class XI.NCERT.

- "The Constituent Assembly Debates (Proceedings): 9 December 1946 to 24 January 1950".The Parliament of India Archive. Archived fromthe originalon 29 September 2007.Retrieved22 February2008.

External links

- The Constitution of India

- Original as published in the Gazette of India

- Original Unamended version of the Constitution of India

- Ministry of Law and Justice of India – The Constitution of India Page

- Constitution of India as of 29 July 2008

- Constitutional predilections

- "Constitution of India".Commonwealth Legal Information Institute.Archived fromthe originalon 22 October 2008.– online copy