Torii

Atorii(Japanese:Điểu cư,[to.ɾi.i])is a traditionalJapanesegate most commonly found at the entrance of or within aShinto shrine,where it symbolically marks the transition from the mundane to the sacred,[1]and a spot wherekamiare welcomed and thought to travel through.[2]

The presence of atoriiat the entrance is usually the simplest way to identify Shinto shrines, and a smalltoriiicon represents them on Japanese road maps and onGoogle Maps.

The first appearance oftoriigates in Japan can be reliably pinpointed to at least the mid-Heian period;they are mentioned in a text written in 922.[1]The oldest existing stonetoriiwas built in the 12th century and belongs to aHachiman shrineinYamagata Prefecture.The oldest existing woodentoriiis aryōbu torii(see description below) at Kubō Hachiman Shrine inYamanashi Prefecturebuilt in 1535.[1]

Toriigates were traditionally made from wood or stone, but today they can be also made of reinforced concrete, stainless steel or other materials. They are usually either unpainted or paintedvermilionwith a black upperlintel.Shrines of Inari,thekamiof fertility and industry, typically have manytoriibecause those who have been successful in business often donatetoriiin gratitude.Fushimi Inari-taishainKyotohas thousands of suchtorii,each bearing the donor's name.[3]

Uses

[edit]

The function of atoriiis to mark the entrance to a sacred space. For this reason, the road leading to a Shinto shrine (sandō) is almost always straddled by one or moretorii,which are therefore the easiest way to distinguish a shrine from a Buddhist temple. If thesandōpasses under multipletorii,the outer of them is calledichi no torii(Nhất の điểu cư,first torii).[4]The following ones, closer to the shrine, are usually called, in order,ni no torii(Nhị の điểu cư,second torii)andsan no torii(Tam の điểu cư,third torii).Othertoriican be found farther into the shrine to represent increasing levels of holiness as one nears the inner sanctuary (honden), core of the shrine.[4]Also, because of the strong relationship between Shinto shrines and the JapaneseImperial family,atoriistands also in front of the tomb of each Emperor.

In the pasttoriimust have been used also at the entrance of Buddhist temples. Even today, as prominent a temple asOsaka'sShitennō-ji,founded in 593 byShōtoku Taishiand the oldest state-built Buddhist temple in the country (and world), has atoriistraddling one of its entrances.[5](The original woodentoriiburned in 1294 and was then replaced by one in stone.) Many Buddhist temples include one or more Shinto shrines dedicated to their tutelarykami( "Chinjusha"), and in that case atoriimarks the shrine's entrance.Benzaitenis asyncreticgoddess derived from the Indian divinitySarasvati,who unites elements of bothShintoandBuddhism.For this reason halls dedicated to her can be found at both temples and shrines, and in either case in front of the hall stands atorii.The goddess herself is sometimes portrayed with atoriion her head.[5] Finally, until theMeiji period(1868–1912)toriiwere routinely adorned with plaques carrying Buddhistsutras.[6]

Yamabushi,Japanese mountain ascetic hermits with a long tradition as mighty warriors endowed with supernatural powers, sometimes use as their symbol atorii.[5]

Thetoriiis also sometimes used as a symbol of Japan in non-religious contexts. For example, it is the symbol of theMarine Corps Security Force Regimentand the187th Infantry Regiment, 101st Airborne Divisionand of other US forces in Japan.[citation needed]It is also used as a fixture at the entrance of someJapantowncommunities, such asLiberdadeinSão Paulo.

Origins

[edit]The origins of thetoriiare unknown and there are several different theories on the subject, none of which has gained universal acceptance.[4]Because the use of symbolic gates is widespread in Asia—such structures can be found for example inIndia,China,Thailand,Korea,and withinNicobareseandShompenvillages—many historians believe they may be an imported tradition.

They may, for example, have originated in India from thetoranagates in the monastery ofSanchiin central India.[1]According to this theory, thetoranawas adopted byShingon BuddhismfounderKūkai,who used it to demarcate the sacred space used for thehomaceremony.[7]The hypothesis arose in the 19th and 20th centuries due to similarities in structure and name between the two gates. Linguistic and historical objections have now emerged, but no conclusion has yet been reached.[5]

InBangkok,Thailand, aBrahminstructure calledSao Ching Chastrongly resembles atorii.Functionally, however, it is very different as it is used as aswing.[5]that was constructed in 1784 in front of the Devasathan shrine by King Rama I. During the reign of Rama II the swing ceremony was discontinued as the swing had become structurally damaged by lightning.

Other theories claimtoriimay be related to thepailouof China. These structures however can assume a great variety of forms, only some of which actually somewhat resemble atorii.[5]The same goes for Korea's "hongsal-mun".[8][9]Unlike its Chinese counterpart, the hongsal-mun does not vary greatly in design and is always painted red, with "arrowsticks" located on the top of the structure (hence the name).

-

An Indiantorana

-

A Chinesepailou

-

A Vietnamesetam quan

-

A Koreanhongsalmun

Various tentativeetymologiesof the wordtoriiexist. According to one of them, the name derives from the termtōri-iru(Thông り nhập る,pass through and enter).[4]

Another hypothesis takes the name literally: the gate would originally have been some kind of bird perch. This is based on the religious use of bird perches in Asia, such as the Koreansotdae(솟대), which are poles with one or more wooden birds resting on their top. Commonly found in groups at the entrance of villages together withtotem polescalledjangseung,they aretalismanswhich ward off evil spirits and bring the villagers good luck. "Bird perches" similar in form and function to thesotdaeexist also in othershamanisticcultures in China,MongoliaandSiberia.Although they do not look liketoriiand serve a different function, these "bird perches" show how birds in several Asian cultures are believed to have magic or spiritual properties, and may therefore help explain the enigmatic literal meaning of thetorii'sname ( "bird perch" ).[5][note 1]

Poles believed to have supported wooden bird figures very similar to thesotdaehave been found together with wooden birds, and are believed by some historians to have somehow evolved into today'storii.[10]Intriguingly, in both Korea and Japan single poles represent deities (kamiin the case of Japan) andhashira(Trụ,pole)is thecounterforkami.[6]

In Japan birds have also long had a connection with the dead, this may mean it was born in connection with some prehistorical funerary rite. Ancient Japanese texts like theKojikiand theNihon Shokifor example mention howYamato Takeruafter his death became a white bird and in that form chose a place for his own burial.[5]For this reason, his mausoleum was then calledshiratori misasagi(Bạch điểu lăng,white bird grave).Many later texts also show some relationship between dead souls and white birds, a link common also in other cultures, shamanic like the Japanese. Bird motifs from theYayoiandKofun periodsassociating birds with the dead have also been found in several archeological sites. This relationship between birds and death would also explain why, in spite of their name, no visible trace of birds remains in today'storii:birds were symbols of death, which in Shinto brings defilement (kegare).[5]

Finally, the possibility thattoriiare a Japanese invention cannot be discounted. The firsttoriicould have evolved already with their present function through the following sequence of events:

- Four posts were placed at the corners of a sacred area and connected with a rope, thus dividing sacred and mundane.

- Two taller posts were then placed at the center of the most auspicious direction, to let the priest in.

- A rope was tied from one post to the other to mark the border between the outside and the inside, the sacred and the mundane. This hypothetical stage corresponds to a type oftoriiin actual use, the so-calledshime-torii(Chú liên điểu cư),an example of whichcan be seenin front ofŌmiwa Shrine'shaideninNara(see also the photo in the gallery).

- The rope was replaced by a lintel.

- Because the gate was structurally weak, it was reinforced with a tie-beam, and what is today calledshinmei torii(Thần minh điểu cư)orfutabashira torii(Nhị trụ điểu cư,two pillar torii)(see illustration at right) was born.[1]This theory however does nothing to explain how the gates got their name.

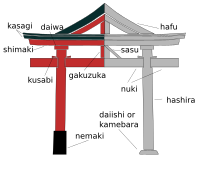

Theshinmei torii,whose structure agrees with the historians' reconstruction, consists of just four unbarked and unpainted logs: two vertical pillars (hashira(Trụ)) topped by a horizontallintel(kasagi(Lạp mộc)) and kept together by a tie-beam (nuki(Quán)).[1]The pillars may have a slight inward inclination calleduchikorobi(Nội 転び)or justkorobi(転び).Its parts are always straight.

Parts and ornamentations

[edit]

- Toriimay be unpainted or painted vermilion and black. The color black is limited to thekasagiand thenemaki(Căn quyển,see illustration).Very rarelytoriican be found also in other colors.Kamakura'sKamakura-gūfor example has a white and red one.

- Thekasagimay be reinforced underneath by a second horizontal lintel calledshimakiorshimagi(Đảo mộc).[11]

- Kasagiand theshimakimay have an upward curve calledsorimashi(Phản り tăng し).[12]

- Thenukiis often held in place by wedges (kusabi(Tiết)). Thekusabiin many cases are purely ornamental.

- At the center of thenukithere may be a supporting strut calledgakuzuka(Ngạch thúc),sometimes covered by a tablet carrying the name of the shrine (see photo in the gallery).

- The pillars often rest on a white stone ring calledkamebara(Quy phúc,turtle belly)ordaiishi(Đài thạch,base stone).The stone is sometimes replaced by a decorative black sleeve callednemaki(Căn quyển,root sleeve).

- At the top of the pillars there may be a decorative ring called daiwa(Đài luân,architrave).[1]

- The gate has a purely symbolic function and therefore there usually are no doors or board fences, but exceptions exist, as for example in the case ofŌmiwa Shrine's triple-archedtorii(miwa torii,see below).[13]

Styles

[edit]Structurally, the simplest is theshime toriiorchūren torii(Chú liên điểu cư)(see illustration below).[note 2]Probably one of the oldest types of torii, it consists of two posts with a sacred rope calledshimenawatied between them.[14]

All othertoriican be divided in two families, theshinmeifamily(Thần minh hệ)and themyōjinfamily(Minh thần hệ).[1][note 3]Toriiof the first have only straight parts, the second have both straight and curved parts.[1]

Shinmeifamily

[edit]Theshinmei toriiand its variants are characterized by straight upper lintels.

-

Shime torii– just two posts and ashimenawa

-

Shinmei torii

-

Ise torii– ashinmei toriiwith akasagipentagonal in section, ashimakiandkusabi

-

Kashima torii– ashinmei toriiwithkusabiand anukiprotruding from the sides

-

Kasuga torii– amyōjin toriiwith straight top lintels cut at a square angle

-

Hachiman torii– akasuga torii,but the two lintels have a downwards slant.

-

Mihashira torii– a tripleshinmei torii

Photo gallery

[edit]-

Torii or traditional Japanese gate. Heian-jingū. Sakyō-ku, Kyoto.

-

Beachside torii on the island ofNaoshima

-

Ise torii,first type. Note the presence ofkasagi.

-

Ise torii,second type. Note theshimaki.

-

Hachiman torii

-

Mihashira torii

-

Ashiroki torii

-

Torii in theHida Minzoku Mura Folk Village

Shinmei torii

[edit]Theshinmei torii(Thần minh điểu cư),which gives the name to the family, is constituted solely by alintel(kasagi) and two pillars (hashira) united by a tie beam (nuki).[15]In its simplest form, all four elements are rounded and the pillars have no inclination. When thenukiis rectangular in section, it is calledYasukuni torii,from Tokyo'sYasukuni Jinja.[16]It is believed to be the oldesttoriistyle.[1]

Ise torii

[edit]Y thế điểu cư(Ise torii)(see illustration above) are gates found only at the Inner Shrine and Outer Shrine atIse ShrineinMie Prefecture.For this reason, they are also calledJingū torii,from Jingū, Ise Grand Shrine's official Japanese name.[14]

There are two variants. The most common is extremely similar to ashinmei torii,its pillars however have a slight inward inclination and itsnukiis kept in place by wedges (kusabi). Thekasagiis pentagonal in section (see illustration in the gallery below). The ends of thekasagiare slightly thicker, giving the impression of an upward slant. All thesetoriiwere built after the 14th century.

The second type is similar to the first, but has also a secondary, rectangular lintel (shimaki) under the pentagonalkasagi.[17]

This and theshinmei toriistyle started becoming more popular during the early 20th century at the time ofState Shintobecause they were considered the oldest and most prestigious.[5]

Kasuga torii

[edit]TheKasuga torii(Xuân nhật điểu cư)is amyōjin torii(see illustration above) with straight top lintels. The style takes its name fromKasuga-taisha'sichi-no-torii(Nhất の điểu cư),or maintorii.

The pillars have an inclination and are slightly tapered. Thenukiprotrudes and is held in place bykusabidriven in on both sides.[18]

Thistoriiwas the first to be painted vermilion and to adopt ashimakiatKasuga Taisha,the shrine from which it takes its name.[14]

Hachiman torii

[edit]Almost identical to akasuga torii(see illustration above), but with the two upper lintels at a slant, theHachiman torii(Bát phiên điểu cư)first appeared during theHeian period.[14]The name comes from the fact that this type oftoriiis often used at Hachiman shrines.

Kashima torii

[edit]Thekashima torii(Lộc đảo điểu cư)(see illustration above) is ashinmei toriiwithoutkorobi,withkusabiand a protruding nuki. It takes its name fromKashima ShrineinIbaraki Prefecture.

Kuroki torii

[edit]Thekuroki torii(Hắc mộc điểu cư)is ashinmei toriibuilt with unbarked wood. Because this type oftoriirequires replacement at three years intervals, it is becoming rare. The most notorious example isNonomiya Shrinein Kyoto. The shrine now however uses atoriimade of synthetic material which simulates the look of wood.

Shiromaruta torii

[edit]Theshiromarutatorii(Bạch hoàn thái điểu cư)orshiroki torii(Bạch mộc điểu cư)is ashinmei toriimade with logs from which bark has been removed. This type oftoriiis present at the tombs of all Emperors of Japan.

Mihashira torii

[edit]Themihashira toriiorMitsubashira Torii(Tam trụ điểu cư,Three-pillar Torii,also tam giác điểu cưsankaku torii)(see illustration above) is a type oftoriiwhich appears to be formed from three individualtorii(see gallery). It is thought by some to have been built by early JapaneseChristiansto represent theHoly Trinity.[19]

Myōjinfamily

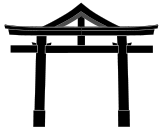

[edit]TheMyōjin toriiand its variants are characterized by curved lintels.

-

Myōjin torii–kasagiandshimakiare curved upwards.

-

Nakayama torii– amyōjin torii,but thenukidoes not protrude from the pillars.

-

DaiwaorInari torii– Amyōjin toriiwith rings at the top of the pillars

-

Ryōbu torii– adaiwa toriiwith pillars supported on both sides

-

Miwa torii– a triplemyōjin torii

-

Usa torii– amyōjin toriiwith nogakuzuka

-

Nune torii– adaiwa toriiwith a small gable above thegakuzuka

-

Sannō torii– amyōjin toriiwith a gable above thekasagi

-

Hizen torii– an unusual style with a roundedkasagiand thick, flared pillars[note 4]

Photo gallery

[edit]-

Myōjin torii

-

Sannō torii

-

Daiwa torii.Note thenemaki.

-

TheSumiyoshi toriihas pillars with a square cross-section.

-

Nakayama torii

-

Ryōbu torii

-

Miwa Torii

-

Thehizen torii(Phì tiền điểu cư)has a roundedkasagiand thick flared pillars.

-

Senbon toriiatFushimi Inari-taisha

Myōjin torii

[edit]Themyōjin torii(Minh thần điểu cư),by far the most commontoriistyle, are characterized by curved upper lintels (kasagiandshimaki). Both curve slightly upwards. Kusabi are present. Amyōjin toriican be made of wood, stone, concrete or other materials and be vermilion or unpainted.

Nakayama torii

[edit]The Nakayamatorii(Trung sơn điểu cư)style, which takes its name from Nakayama Jinja inOkayama Prefecture,is basically amyōjin torii,but thenukidoes not protrude from the pillars and the curve made by the two top lintels is more accentuated than usual. Thetoriiat Nakayama Shrine that gives the style its name is 9 m tall and was erected in 1791.[14]

Daiwa / Inari torii

[edit]Thedaiwa orInaritorii(Đại luân điểu cư ・ đạo hà điểu cư)(see illustration above) is amyōjin toriiwith two rings calleddaiwaat the top of the two pillars. The name "Inari torii" comes from the fact that vermiliondaiwa toriitend to be common atInari shrines,but even at the famousFushimi Inari Shrinenot alltoriiare in this style. This style first appeared during the late Heian period.

Sannō torii

[edit]Thesannō torii(Sơn vương điểu cư)(see photo below) ismyōjin toriiwith a gable over the two top lintels. The best example of this style is found atHiyoshi Shrinenear Lake Biwa.[14]

Miwa torii

[edit]Also calledsankō torii(Tam quang điểu cư,three light torii),mitsutorii(Tam điểu cư,triple torii)orkomochi torii(Tử trì ち điểu cư,torii with children)(see illustration above), themiwa torii(Tam luân điểu cư)is composed of threemyōjin toriiwithout inclination of the pillars. It can be found with or without doors. The most famous one is at Ōmiwa Shrine, in Nara, from which it takes its name.[14]

Ryōbu torii

[edit]Also calledyotsuashi torii(Tứ cước điểu cư,four-legged torii),gongentorii(権 hiện điểu cư)orchigobashira torii(Trĩ nhi trụ điểu cư),theryōbu torii(Lạng bộ điểu cư)is adaiwa toriiwhose pillars are reinforced on both sides by square posts (see illustration above).[20]The name derives from its long association with Ryōbu Shintō, a current of thought withinShingon Buddhism.The famoustoriirising from the water at Itsukushima is aryōbu torii,and the shrine used to be also a ShingonBuddhist temple,so much so that it still has apagoda.[21]

Hizen torii

[edit]Thehizen torii(Phì tiền điểu cư)is an unusual type of torii with a roundedkasagiand pillars that flare downwards. They are found only inSaga prefectureand the neighboring areas.[22]

Gallery

[edit]-

A tablet on atoriiatNikkō Tōshō-gūcovers thegakuzuka.

-

The typical pentagonal profile of atorii'skasagi.Note the blacknemaki.

-

A row oftorii

-

One-legged torii,Sannō Shrine,Nagasaki, Japan. The other half was toppled in the explosion of the nuclear bomb.

-

An unusual white and redNakayama torii

-

Ashime torii

-

Rows of tiny votivetoriidonated by the faithful[note 5]

-

An unusualkaku-torii(Giác điểu cư,lit. square torii)at Sumiyoshi Taisha: thenukidoes not protrude and all members are square in section.

-

A temporary Torii for new year celebration in a shopping street decorated with Christmas lights

-

An example of a Hizen style gate

See also

[edit]- Dvarapala,is a door or gate guardian often portrayed as a warrior or fearsome giant, usually armed with a weapon.

- Hongsalmun,in Korean architecture with both religious and other usage

- Iljumun,portal in Korean temple architecture

- Mon (architecture)

- Paifang,in Chinese temple architecture

- Tam quan,in Vietnamese temple architecture

- Torana,a Hindu-Buddhist ceremonial arched gateway

Notes

[edit]- ^Toriiused to be also calleduefukazu-no-mikadooruefukazu-no-gomon(Ô thượng bất tập ngự môn,roofless gate).The presence of the honorificMi-orGo-makes it likely that by then their use was already associated with shrines.

- ^The two names are simply different readings of the same characters.

- ^Other ways of classifyingtoriiexist, based for example on the presence or absence of theshimaki.See for example the siteJinja Chishiki.

- ^This example is the main torii of Kashii Shrine,Saga prefecture

- ^At Kamakura'sZeniarai BentenShrine

References

[edit]- ^abcdefghij"Torii".JAANUS.2001.Retrieved2 September2023.

- ^Pearson, Patricia O'Connell; Holdren, John (May 2021).World History: Our Human Story.Versailles, Kentucky: Sheridan Kentucky. p. 294.ISBN978-1-60153-123-0.

- ^"Historical Items about Japan".Michelle Jarboe. 11 May 2007. Archived fromthe originalon 6 January 2010.Retrieved10 February2010.

- ^abcd"Torii".Encyclopedia of Shinto.Kokugakuin University.2 June 2005. Archived fromthe originalon 22 July 2011.Retrieved21 February2010.

- ^abcdefghijScheid, Bernhard."Torii".Religion in Japan(in German). University of Vienna.Retrieved4 April2022.

- ^abBocking, Brian (1997).A Popular Dictionary of Shinto.Routledge.ISBN978-0-7007-1051-5.

- ^James Edward Ketelaar.Of Heretics and Martyrs in Meiji Japan.Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1990. p.59.

- ^Guisso, Richard W. I.; Yu, Chai-Shin (1 January 1988).Shamanism: The Spirit World of Korea.Jain Publishing Company. p. 56.ISBN9780895818867.Retrieved5 January2016.

- ^Bocking, Brian (30 September 2005).A Popular Dictionary of Shinto.Routledge. p. 319.ISBN9781135797386.Retrieved5 January2016.

- ^"Onrain Shoten BK1: Kyoboku to torizao Yūgaku Sōsho"(in Japanese).Retrieved22 February2010.

- ^IwanamiKōjien(Quảng từ uyển)Japanese dictionary, 6th Edition (2008), DVD version

- ^"Torii no iroiro"(in Japanese).Retrieved25 February2010.

- ^"JAANUS".Toriimon.Retrieved15 January2010.

- ^abcdefgPicken, Stuart (22 November 1994).Essentials of Shinto: An Analytical Guide to Principal Teachings (Resources in Asian Philosophy and Religion).Greenwood. pp.148–160.ISBN978-0-313-26431-3.

- ^"JAANUS".Shinmei torii.Retrieved14 January2010.

- ^"Torii no bunrui"(in Japanese).Retrieved25 February2010.

- ^"JAANUS".Ise torii.Retrieved15 January2010.

- ^"JAANUS".Kasuga torii.Retrieved15 January2010.

- ^"mihashira torii tam trụ điểu cư."JAANUS. Retrieved on September 4, 2018.

- ^Parent, Mary Neighbour."Ryoubu torii".Japanese Architecture and Art Net Users System.Retrieved28 June2011.

- ^Hamashima, Masashi (1999).Jisha Kenchiku no Kanshō Kiso Chishiki(in Japanese). Tokyo: Shibundō. p. 88.

- ^"Đạo tá thần xã の phì tiền điểu cư が tá hạ huyện trọng yếu văn hóa tài ( kiến tạo vật ) に chỉ định されました".Shiroishi, Saga Official.Retrieved16 September2021.

External links

[edit] Media related toToriiat Wikimedia Commons

Media related toToriiat Wikimedia Commons