Sahelanthropus

| Sahelanthropus tchadensis "Toumaï" Temporal range:Messinian,

| |

|---|---|

| |

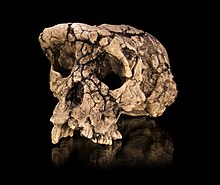

| Cast of the skull of Toumaï | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Primates |

| Suborder: | Haplorhini |

| Infraorder: | Simiiformes |

| Family: | Hominidae |

| Genus: | †Sahelanthropus Brunetet al.,2002[1] |

| Species: | †S. tchadensis

|

| Binomial name | |

| †Sahelanthropus tchadensis Brunetet al.,2002[1]

| |

Sahelanthropusis anextinctgenus ofhominiddated to about7million years agoduring theLate Miocene.The type species,Sahelanthropus tchadensis,was first announced in 2002, based mainly on a partialcranium,nicknamedToumaï,discovered in northernChad.

The definitive phylogenetic position ofSahelanthropuswithin hominids is uncertain. It was initially described as a possiblehomininancestral to bothhumansandchimpanzees,but subsequent interpretations suggest that it could be an early member of the tribeGorillinior a stem-hominid outside the hominins. Examinations on the postcranial skeleton ofSahelanthropusalso indicated that this taxon was not a habitual biped.

Taxonomy[edit]

Discovery[edit]

Four employees of the Centre National d'Appui à la Recherche (CNAR, National Research Support Center) of the Ministry of Higher Education of the Republic of Chad, three Chadians (Ahounta Djimdoumalbaye,[2]Fanoné Gongdibé and Mahamat Adoum) and one French (Alain Beauvilain[3]) collected and identified the first remains in the Toros-Menalla area (TM 266locality) in theDjurab Desertof northern Chad, July 19, 2001. By the timeMichel Brunetand colleagues formally described the remains in 2002, a total of six specimens had been recovered: a nearly complete but heavily deformed skull, a fragment of the midline of the jaw with thetooth socketsfor anincisorandcanine,a right thirdmolar,a right first incisor, a right jawbone with the lastpremolarto last molar, and a right canine. With the skull as theholotype specimen,they were grouped into a newgenusandspeciesasSahelanthropus tchadensis,the genus name referring to theSahel,and the species name to Chad. These, along withAustralopithecus bahrelghazali,were the first discoveries of any fossil Africangreat ape(outside the genusHomo) made beyond eastern and southern Africa.[1]By 2005, a third premolar was recovered from the TM 266 locality, a lower jaw missing the region behind the second molar from the TM 292 locality, and a lower left jaw preserving the sockets for premolars and molars from the TM 247 locality.[4]

The skull was nicknamed Toumaï by the then-president of the Republic of Chad,Idriss Déby,not only because it designates in the localDaza languagemeaning "hope of life", given to infants born just before the dry season and who, therefore, have fairly limited chances of survival, but also to celebrate the memory of one of his comrades-in-arms, living in the north of the country where the fossil was discovered, and killed fighting to overthrow PresidentHissène Habrésupported by France.[5]Toumaï also became a source of national pride, and Brunet announced the discovery before the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and a television audience in the capital ofN'Djamena,"l'ancêtre de l'humanité est Tchadien...Le berceau de l'humanité se trouve au Tchad. Toumaï est votre ancêtre"(" The ancestor of humanity is Chadian...The cradle of humanity is in Chad. Toumaï is your ancestor. ")[6][7].

Toumaï had been found with a femur, but this was stored with animal bones and shipped to theUniversity of Poitiersin 2003, where it was stumbled upon by graduate student Aude Bergeret the next year. She took the bone to the head of the Department of Geosciences, Roberto Macchiarelli, who considered it to be inconsistent withbipedalismcontra what Brunetet al.had earlier stated in their description analysing only the distorted skull. This was conspicuous because Brunet and his team had already explicitly stated Toumaï was associated with no limb bones, which could have proven or disproven their conclusions of locomotion. Because Brunet had declined to comment on the subject, Macchiarelli and Bergeret petitioned to present their preliminary findings during an annual conference organised by theAnthropological Society of Paris,which would be held at Poitiers that year. This was rejected as they had not formally published their findings yet.[8][9]They were able to publish a full description in 2020, and concludedSahelanthropuswas not bipedal.[10]

In 2022, French primatologist Franck Guy and colleagues reported that a hominin left femur (TM 266-01-063), and a right (TM 266-01-358) and a left (TM 266-01-050)ulna(forearm bone) were also discovered at the site in 2001, but were excluded originally fromSahelanthropusbecause they could not be reliably associated with the skull. They decided to include it becauseSahelanthropusis the only hominin known from the site, and they concluded that the material is consistent with obligate bipedalism, the earliest evidence of such.[11]In 2023, Meyer and colleagues suggested that its phylogenetic position and its status as a hominin still remain equivocal.[12]

AllSahelanthropusspecimens, representing six to nine different adults, have been recovered within the 0.73 km2(0.28 sq mi) area.[10]

Taphonomy[edit]

Upon description, Brunet and colleagues were able to constrain the TM 266 locality to 7 or 6 million years ago (near the end of theLate Miocene) based on the animal assemblage, which madeSahelanthropusthe earliest African ape at the time.[1]In 2008, Anne-Elisabeth Lebatard and colleagues (which includes Brunet) attempted toradiometrically dateusing the10Be/9Beratio the sediments Toumaï was found near (dubbed the "anthracotheriidunit "after the commonplaceLibycosaurus petrochii). Averaging the ages of 28 samples, they reported an approximate date of 7.2–6.8 million years ago.[13]

Their methods were soon challenged by Beauvilain, who clarified that Toumaï was found on loose sediments at the surface rather than being "unearthed", and had probably been exposed to the harsh sun and wind for some time considering it was encrusted in an iron shell anddesert varnish.This would mean it is unsafe to assume that the skull and nearby sediments were deposited at the same time, making such radiometric dating impossible.[14]Further, theSahelanthropusfossils lack whitesilaceouscementwhich is present on every other fossil in the site, which would mean they date to different time periods. Because the large mammal fossils were scattered across the area instead of concentrated like theSahelanthropusfossils, the discoverers originally believed theSahelanthropusfossils were dumped there by a palaeontologist or geologist, but later dismissed this because the skull was too complete to have been thrown away like that. In 2009, Alain Beauvilain andJean-Pierre Watté[15]argued that Toumaï was purposefully buried in a "grave", because the skull was also found with two parallel rows of large mammal fossils, seemingly forming a 100 cm × 40 cm (3.3 ft × 1.3 ft) box. Because the "grave" is orientated in a northeast–southwest direction towardsMecca,and all sides of the skull were exposed to the wind and were eroded (meaning the skull had somehow turned), they argued that Toumaï was first buried by nomads who identified the skull as human and collected nearby limb fossils (believing them to belong with the skull) and buried them, and was reburied again sometime after the 11th century by Muslims who reorientated the grave towards Mecca when the fossils were re-exposed.[16]

Classification[edit]

−10 — – −9 — – −8 — – −7 — – −6 — – −5 — – −4 — – −3 — – −2 — – −1 — – 0 — |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

When describing the species in 2002, Brunetet al.noted the combination of features that would be considered archaic or derived for a species on the human line (thesubtribeHominina), the latter being bipedal locomotion and reducedcanine teeth,which they interpreted as evidence of its position near thechimpanzee–human last common ancestor(CHLCA). This classification madeSahelanthropusthe oldest Hominina, shifting the centre of origin for thecladeaway from East Africa. They also suggested thatSahelanthropuscould be asister groupto the 5.5-to-4.5-million-year-oldArdipithecusand later Hominina.[1]The classification ofSahelanthropusin Hominina, as well asArdipithecusand the 6-million-year-oldOrrorin,was at odds with molecular analyses of the time, which had placed the CHLCA between 6 and 4 million years ago based on a highmutation rateof about 70 mutations per generation. All these genera were anatomically too derived to represent a basalhominin(the group containing chimps and humans), so molecular data would only permit their classification into more ancient and now-extinct lineages. This was overturned in 2012 by geneticistsAylwyn ScallyandRichard Durbin,who studied the genomes of children and their parents and found the mutation rate was actually half that, placing the CHLCA anywhere from 14 to 7 million years ago, though most geneticists and palaeoanthropologists use 8 to 7 million years ago.[17]A recent phylogenetic analysis classifiedOrrorinas a hominin, but placedSahelanthropusas a stem-hominid outside hominins.[18]

A further possibility is that Toumaï is not ancestral to either humans or chimpanzees at all, but rather an early representative of theGorillinilineage.Brigitte SenutandMartin Pickford,the discoverers ofOrrorintugenensis,suggested that the features ofS. tchadensisare consistent with a female proto-gorilla.Even if this claim is upheld the find would lose none of its significance, because at present very few chimpanzee or gorilla ancestors have been found anywhere in Africa. Thus, ifS. tchadensisis an ancestral relative of the chimpanzees or gorillas, then it represents the earliest known member oftheirlineage.S. tchadensisdoes indicate that the last common ancestor of humans and chimpanzees is unlikely to closely resemble extant chimpanzees, as had been previously supposed by some paleontologists.[19][20]Additionally, with the significantsexual dimorphismknown to have existed in early hominins, the difference betweenArdipithecusandSahelanthropusmay not be large enough to warrant a separate species for the latter.[21]

Anatomy[edit]

Existing fossils include a relatively smallcranium,five pieces ofjaw,and someteeth,making up a head that has a mixture of derived and primitive features. A virtual reconstruction of the interior of the braincase indicated a cranial capacity of 378 cm3,similar to that of extant chimpanzees and approximately a third the size of modern human brains.[22]

The teeth, brow ridges, and facial structure differ markedly from those found in modern humans. Cranial features show a flatter face, U-shaped tooth rows, smallcanines,an anteriorforamen magnum,and heavy brow ridges. The only known skull suffered a large amount of distortion during the time of fossilisation and discovery, as the cranium is dorsoventrally flattened, and the right side is depressed.[1]

In the original description in 2002, Brunetet al.said it "would not be unreasonable" to speculate thatSahelanthropuswas capable of maintaining an upright posture while walkingbipedally.Because they had not reported any limb bones or other post-cranial material (anything other than the skull), this was based on the reconstructed original orientation of theforamen magnum(where the skull connects the spine), and their classification ofSahelanthropusinto Hominina based on facial comparisons (one of the diagnostic characteristics of Hominina is bipedalism).[1]This was soon disputed because the orientation of the foramen magnum is not an entirely conclusive piece of evidence in regard to the question of habitual posture, and the features used to classifySahelanthropusinto Hominina are not entirely unique to Hominina.[23]In 2020, the femur had been formally described, and the study concluded it was not consistent with habitual bipedalism.[10]In 2022, Dayer and colleagues suggested that the postcranial evidence including ulnar and femoral morphologies show characteristics consistent with habitual bipedalism.[11]In 2023, however, Meyer and colleagues examined its ulna shaft and argued thatSahelanthropusis not an obligate biped based on the mathematical analysis of its locomotor behavior which indicated that its forelimbs had different functions compared to modern humans and hominins, and that it probablywalked on its knuckleslike modern gorillas and chimpanzees, so more examination is required to truly identify its locomotor behavior (i.e. whether it exhibitedfacultative bipedalism) and its phylogenetic position as a hominin in the evolution of humans.[12]A 2024 study re-examined the 2022 study's postcranial evidence, and concluded that it is not sufficient to determine whetherSahelanthropuswas a habitual biped, since none of the features are consistent with or unique to bipedal hominins, but with non-hominin hominoids or even non-primates.[24]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^abcdefgBrunet, M.; Guy, F.; Pilbeam, D.; et al. (2002)."A new hominid from the Upper Miocene of Chad, Central Africa"(PDF).Nature.418(6894): 145–151.Bibcode:2002Natur.418..145B.doi:10.1038/nature00879.PMID12110880.S2CID1316969.

- ^"Ahounta Djimdoumalbaye".ResearchGate.Retrieved23 January2023.

- ^"Alain Beauvilain".ResearchGate.

- ^Brunet, M.;Guy, F.;Pilbeam, D.;Lieberman, D. E.; Likius, A.; Mackaye, H. T.; Ponce; de Leon, M. S.; Zollikofer, C. P. E.; Vignaud, P. (2005)."New material of the earliest hominid from the Upper Miocene of Chad"(PDF).Nature.434(7034): 752–755.Bibcode:2005Natur.434..752B.doi:10.1038/nature03392.PMID15815627.S2CID3726177.

- ^The skull discovered in Chad bears the name of a comrade of the Chadian president who died in combatDispatch ofAssociated Press,Denver, July 11, 2002.

- ^"Sahelanthropus tchadensis: Découverte de Toumaï, un" Tchadien "de 7 millions d'années".Retrieved2020-01-01.

- ^N'Djamena, Conference of July 10, 2002,at 1h 0' 30 "

- ^Callaway, Ewen (25 January 2018)."Femur findings remain a secret"(PDF).Nature.553(7689): 391–92.Bibcode:2018Natur.553..391C.doi:10.1038/d41586-018-00972-z.PMID29368713.

- ^Constans, Nicolas (2018-01-23)."L'histoire du Fémur de Toumaï"[The history of Toumai's thighbone] (in French).Retrieved2020-01-01.

- ^abcMacchiarelli, Roberto; Bergeret-Medina, Aude; Marchi, Damiano; Wood, Bernard (2020)."Nature and relationships ofSahelanthropus tchadensis".Journal of Human Evolution.149:102898.doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2020.102898.hdl:11568/1060874.PMID33142154.S2CID226249337.

- ^abDaver, G.; Guy, F.; Mackaye, H. T.; Likius, A.; Boisserie, J. -R.; Moussa, A.; Pallas, L.; Vignaud, P.; Clarisse, N. D. (2022-08-24)."Postcranial evidence of late Miocene hominin bipedalism in Chad"(PDF).Nature.609(7925). Springer Science and Business Media LLC: 94–100.Bibcode:2022Natur.609...94D.doi:10.1038/s41586-022-04901-z.ISSN0028-0836.PMID36002567.S2CID234630242.

- ^abMeyer, M. R.; Jung, J. P.; Spear, J. K.; Araiza, I. Fx.; Galway-Witham, J.; Williams, S. A. (2023). "Knuckle-walking inSahelanthropus?Locomotor inferences from the ulnae of fossil hominins and other hominoids ".Journal of Human Evolution.179.103355.doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2023.103355.PMID37003245.S2CID257874795.

- ^Lebatard, A.-E.; Bourles, D. L.; Duringer, P.; Jolivet, M.; Braucher, R.; Carcaillet, J.; Schuster, M.; Arnaud, N.; Monie, P.; Lihoreau, F.; Likius, A.; Mackaye, H. T.; Vignaud, P.;Brunet, M.(2008)."Cosmogenic nuclide dating ofSahelanthropus tchadensisandAustralopithecus bahrelghazali:Mio-Pliocene hominids from Chad ".PNAS.105(9): 3226–3231.Bibcode:2008PNAS..105.3226L.doi:10.1073/pnas.0708015105.PMC2265126.PMID18305174.

- ^Beauvilain, Alain (2008)."The contexts of discovery ofAustralopithecus bahrelghazaliand ofSahelanthropus tchadensis(Toumaï): unearthed, embedded in sandstone or surface collected? ".South African Journal of Science.104(3): 165–168.

- ^"Jean-Pierre Watte | Université de Rennes - Academia.edu".univ-rennes1.academia.edu.

- ^Beauvilain, A.; Watté, J. P. (2009)."Was Toumaï (Sahelanthropus tchadensis) Buried? ".Anthropologie.47(1/2): 1–6.JSTOR26292847.

- ^Brahic, C. (2012). "Our True Dawn".New Scientist.216(2892): 34–37.Bibcode:2012NewSc.216...34B.doi:10.1016/S0262-4079(12)63018-8.

- ^Sevim-Erol, Ayla; Begun, D. R.; Sözer, Ç Sönmez; Mayda, S.; van den Hoek Ostende, L. W.; Martin, R. M. G.; Alçiçek, M. Cihat (2023-08-23)."A new ape from Türkiye and the radiation of late Miocene hominines".Communications Biology.6(1): 842.doi:10.1038/s42003-023-05210-5.ISSN2399-3642.PMC10447513.PMID37612372.

- ^Guy, F.; Lieberman, D.E.; Pilbeam, D.; et al. (2005)."Morphological affinities of theSahelanthropus tchadensis(Late Miocene hominid from Chad) cranium ".PNAS.102(52): 18836–18841.Bibcode:2005PNAS..10218836G.doi:10.1073/pnas.0509564102.PMC1323204.PMID16380424.

- ^Wolpoff, Milford H.;Hawks, John;Senut, Brigitte;Pickford, Martin;Ahern, James (2006)."An Ape ortheApe: Is the Toumaï Cranium TM 266 a Hominid? "(PDF).PaleoAnthropology.2006:36–50.

- ^Haile-Selassie, Yohannes;Suwa, Gen; White, Tim D. (2004). "Late Miocene Teeth from Middle Awash, Ethiopia, and Early Hominid Dental Evolution".Science.303(5663): 1503–1505.Bibcode:2004Sci...303.1503H.doi:10.1126/science.1092978.PMID15001775.S2CID30387762.

- ^Wong, Kate."Brain Shape Confirms Controversial Fossil as Oldest Human Ancestor".Scientific American Blog Network.Retrieved2022-07-19.

- ^Wolpoff, Milford H.;Senut, Brigitte;Pickford, Martin;Hawks, John (2002)."Palaeoanthropology (communication arising): Sahelanthropus or 'Sahelpithecus'?"(PDF).Nature.419(6907): 581–582.Bibcode:2002Natur.419..581W.doi:10.1038/419581a.hdl:2027.42/62951.PMID12374970.S2CID205029762.

- ^Cazenave, M.; Pina, M.; Hammond, A. S.; Böhme, M.; Begun, D. R.; Spassov, N.; Vecino Gazabón, A.; Zanolli, C.; Bergeret-Medina, A.; Marchi, D.; Macchiarelli, R.; Wood, B. (2024). "Postcranial evidence does not support habitual bipedalism inSahelanthropus tchadensis:A reply to Daver et al. (2022) ".Journal of Human Evolution.103557.doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2024.103557.PMID38918139.

Further reading[edit]

- Beauvilain, Alain (2003).Toumaï: l'aventure humaine(in French). Table ronde.ISBN2-7103-2592-6.

- Brunet, Michel (2006).D'Abel à Toumaï: Nomade, chercheur d'os(in French). Odile Jacob.ISBN978-2-7381-1738-0.

- Gibbons, Ann (2006).The first human.Doubleday.ISBN978-0385512268.

- Reader, John (2011).Missing Links: In Search of Human Origins.Oxford University Press.ISBN978-0-19-927685-1.

External links[edit]

- Fossil Hominids: Toumai

- National Geographic: Skull Fossil Opens Window Into Early Period of Human Origins

- New Findings Bolster Case for Ancient Human Ancestor

- Sahelanthropus tchadensis,Toumaï,Detailed composition of the Franco-Chadian palaeoanthropological Mission, the sahara scientific missions, the discovery's context, controversy about the misplacement of a molar, the minimum number of individuals, the geology of the site, was Toumaï buried? and research to date the skull,...

- Sahelanthropusnews reporting by John Hawks

- S. tchadensisreconstruction

- Sahelanthropus tchadensisOrigins – Exploring the Fossil Record – Bradshaw Foundation

- Human Timeline (Interactive)–Smithsonian,National Museum of Natural History(August 2016).