Trans-Saharan trade

Trans-Saharan tradeistradebetweensub-Saharan AfricaandNorth Africathat requires travel across theSahara.Though this trade began inprehistoric times,the peak of trade extended from the 8th century until the early 17th century CE. The Sahara once had adifferent climate and environment.InLibyaandAlgeria,from at least 7000 BCE,pastoralism(the herding of sheep and goats), large settlements and pottery were present. Cattle were introduced to the Central Sahara (Ahaggar) between 4000 to 3500 BCE. Remarkable rock paintings (dated 3500 to 2500 BCE) in arid regions portray flora and fauna that are not present in the modern desert.[1]

As a desert, the Sahara is now a hostile expanse that separates the Mediterranean economy from the economy of theNiger River Basin.AsFernand Braudelpoints out, crossing such a zone, especially without mechanized transport, is worthwhile only when exceptional circumstances cause the expected gain to outweigh the cost and the danger.[2]Trade was conducted bycaravansofcamels.According to Maghrebi explorerIbn Battuta,who once traveled with a caravan, an average one would amount to 1,000 camels, but some caravans were as large as 12,000.[3][4]The caravans would be guided by highly-paidBerbers,who knew the desert and could ensure protection from fellow desertnomads.The caravans' survival relied on careful coordination: runners would be sent ahead tooasesfor water to be shipped out to the caravan when it was still several days away, as the caravans could usually not carry enough to make the full journey. In the mid-14th century CE, Ibn Battuta crossed the desert fromSijilmasavia the salt mines atTaghazato the oasis ofOualata.A guide was sent ahead, and water was brought over a four-day journey fromOualatato meet the caravan.[5]

Culture and religion were also exchanged on the trans-Saharan trade routes. Many West African states eventually adopted Arabic writing and the religion of North Africa, resulting in these states' absorption into theMuslim world.[6]

Early trans-Saharan trade[edit]

Ancient trade spanned the northeastern corner of the Sahara in theNaqadanera.Predynastic Egyptiansin theNaqada I periodtraded withNubiato the south, the oases of theWestern Desertto the west, and the cultures of theeastern Mediterraneanto the east. Many trading routes went from oasis to oasis to resupply on both food and water. These oases were very important.[7]They also importedobsidianfromSenegalto shape blades and other objects.[8]

The overland route through theWadi Hammamatfrom theNileto theRed Seawas known as early aspredynastictimes;[9]drawings depicting Egyptianreed boatshave been found along the path dating to 4000 BCE.[10]Ancientcitiesdating to theFirst Dynasty of Egyptarose along both its Nile and Red Sea junctions,[citation needed]testifying to the route's ancient popularity. It became a major route fromThebesto theRed Sea portofElim,where travelers then moved on to eitherAsia,Arabia or theHorn of Africa.[citation needed]Records exist documenting knowledge of the route amongSenusret I,Seti,Ramesses IVand also, later, theRoman Empire,especially for mining.[citation needed]

TheDarb al-Arbaʿīntrade route, passing throughKhargain the south andAsyutin the north, was used from as early as theOld Kingdomfor the transport and trade ofgold,ivory,spices,wheat,animals and plants.[11]Later,Ancient Romanswould protect the route by lining it with varied forts and small outposts, some guarding large settlements complete with cultivation.[citation needed]Described byHerodotusas a road "traversed... in forty days", it became by his time an important land route facilitating trade betweenNubiaandEgypt,[12]and subsequently became known as the Forty Days Road. FromKobbei,40 kilometres (25 mi) north ofal-Fashir,the route passed through the desert to Bir Natrum, another oasis and salt mine, toWadi Howarbefore proceeding to Egypt.[13]TheDarb el-Arbaintrade route was the easternmost of the central routes.

The westernmost of the three central routes was theGhadames Road,which ran from theNiger RiveratGaonorth toGhatandGhadamesbefore terminating atTripoli.

Next was the easiest of the three routes: theGaramanteanRoad, named after the former rulers of the land it passed through and also called theBilma Trail.TheGaramantean Roadpassed south of the desert nearMurzukbefore turning north to pass between theAlhaggarandTibesti Mountainsbefore reaching the oasis atKawar.From Kawar, caravans would pass over the great sand dunes ofBilma,whererock saltwas mined in great quantities for trade, before reaching the savanna north ofLake Chad.[14]This was the shortest of the routes, and the primary exchanges were slaves andivoryfrom the south for salt. One early 20th century researcher wrote of theTripoli-Murzuk-Lake Chad route,"Most of the [trans-Saharan] traffic from the Mediterranean coast during the last 2,000 years has passed along this road."[15]

Another Libyan route wasBenghazitoKufrato the lands of theWadai Empirebetween Lake Chad and Darfur.[15]

The western routes were theWalata Roadpast present-dayOualata, Mauritania,from theSénégal River,and theTaghaza Trail,from the Niger River, past the salt mines ofTaghaza,north to the great trading center ofSijilmasa,situated inMoroccojust north of the desert.[13]The growth of the city ofAoudaghost,founded in the 5th century BCE, was stimulated by its position at the southern end of a trans-Saharan trade route.[16]

To the east, three ancient routes connected the south to the Mediterranean. The herdsmen of theFezzanofLibya,known as the Garamantes, controlled these routes as early as 1500 BCE. From their capital ofGermain the Wadi Ajal, the Garamantean Empire raided north to the sea and south into the Sahel. By the 4th century BCE, the independent city-states ofPhoeniciahad expanded their control to the territory and routes once held by the Garamantes.[13]Shillington states that existing contact with the Mediterranean received added incentive with the growth of the port city ofCarthage.Founded c. 800 BCE, Carthage became one terminus for West African gold, ivory, and slaves. West Africa received salt, cloth, beads, and metal goods. Shillington proceeds to identify this trade route as the source for West African iron smelting.[17]Trade continued into Roman times. Although there are Classical references to direct travel from the Mediterranean to West Africa (Daniels, p. 22f), most of this trade was conducted through middlemen, inhabiting the area and aware of passages through the drying lands.[18]TheLegio III Augustasubsequently secured these routes on behalf ofRomeby the 1st century CE, safeguarding the southern border of the empire for two and half centuries.[13]

The Garamantes also engaged in thetrans-Saharan slave trade.The Garamantes used slaves in their own communities to construct and maintain underground irrigation systems known as thefoggara.[19]Early records oftrans-Saharan slave tradecome fromancient GreekhistorianHerodotusin the 5th century BCE, who records the Garamantes enslaving cave-dwelling Egyptians in Sudan.[20][21]Two records of Romans accompanying the Garamantes on slave raiding expeditions are recorded - the first in 86 CE and the second a few years later toLake Chad.[20][21]Initial sources of slaves were theToubou people,but by the1st centuryCE, the Garamantes were obtaining slaves from modern dayNigerandChad.[21]

In the earlyRoman Empire,the city ofLepcisestablished aslave marketto buy and sell slaves from the African interior.[20]The empire imposedcustoms taxon the trade of slaves.[20]In the 5th century CE,Roman Carthagewas trading in black slaves brought across the Sahara.[21]Black slaves seem to have been valued in the Mediterranean as household slaves for their exotic appearance.[21]Some historians argue that the scale of slave trade in this period may have been higher than medieval times due to high demand of slaves in the Roman Empire.[21]

Introduction of the camel[edit]

Herodotushad spoken of the Garamantes hunting the EthiopianTroglodyteswith theirchariots;this account was associated with depictions of horses drawing chariots in contemporarycave artin southernMoroccoand theFezzan,giving origin to a theory that the Garamantes, or some other Saharan people, had created chariot routes to provideRomeand Carthage with gold and ivory. However, it has been argued that no horse skeletons have been found dating from this early period in the region, and chariots would have been unlikely vehicles for trading purposes due to their small capacity.[22]

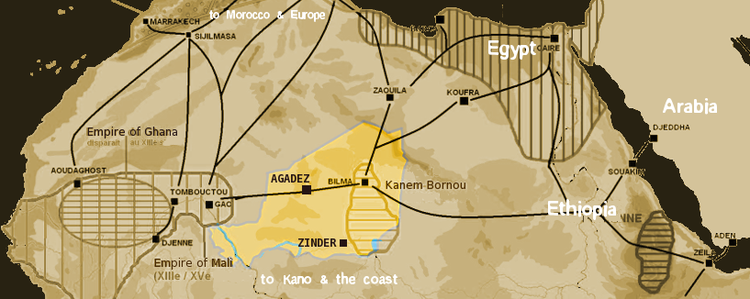

The earliest evidence for domesticatedcamelsin the region dates from the 3rd century. Used by theBerbers,they enabled more regular contact across the entire width of the Sahara, but regular trade routes did not develop until the beginnings of the Islamic conversion of West Africa in the 7th and 8th centuries.[22]Two main trade routes developed. The first ran through the western desert from modernMoroccoto the Niger bend, the second from modernTunisiato theLake Chadarea. These stretches were relatively short and had the essential network of occasional oases that established the routing as inexorably as pins in a map. Further east of the Fezzan with its trade route through the valley ofKaouarto Lake Chad, Libya was impassable due to its lack of oases and fierce sandstorms.[23]A route from the Niger bend to Egypt was abandoned in the 10th century due to its dangers.[citation needed]

Spread of Islam[edit]

Several trade routes became established, perhaps the most important terminating inSijilmasa(Morocco) andIfriqiyato the north. There, and in other North African cities, Berber traders had increased contact with Islam, encouraging conversions, and by the 8th century, Muslims were traveling to Ghana. Many in Ghana converted to Islam, and it is likely that the Empire's trade was privileged as a result. Around 1050, Ghana lostAoudaghostto theAlmoravids,but new goldmines aroundBurereduced trade through the city, instead benefiting theMalinkeof the south, who later founded theMali Empire.

Unlike Ghana, Mali was a Muslim kingdom since its foundation, and under it, the gold–salt trade continued. Other, less important trade goods were slaves,kola nutsfrom the south andslave beadsandcowry shellsfrom the north (for use as currency). It was under Mali that the great cities of theNigerbend—includingGaoandDjenné—prospered, withTimbuktuin particular becoming known across Europe for its great wealth. Important trading centers in southern West Africa developed at the transitional zone between the forest and the savanna; examples includeBeghoandBono Manso(in present-day Ghana) andBondoukou(in present-dayCôte d'Ivoire). Western trade routes continued to be important, withOuadane,OualataandChinguettibeing the major trade centres in what is now Mauritania, while theTuaregtowns ofAssodéand laterAgadezgrew around a more easterly route in what is nowNiger.

The eastern trans-Saharan route led to the development of the long-livedKanem–Bornu Empireas well as the Ghana, Mali, andSonghaiempires, centred on the Lake Chad area. This trade route was somewhat less efficient and only rose to great prominence when there was turmoil in the west such as during theAlmohadconquests.

Thetrans-Saharan slave trade,established inAntiquity,[21]continued during theMiddle Ages.The slaves brought from across the Sahara were mainly used by wealthy families as domestic servants,[24]and concubines.[25]Some served in the military forces of Egypt and Morocco.[25]For example, the 17th century sultanMawlay Ismailhimself was the son of slave, and relied on an army of black slaves for support. The West African states imported highly trained slave soldiers.[25]It has been estimated that from the 10th to the 19th century some 6,000 to 7,000enslaved peoplewere transported north each year.[26][failed verification]Perhaps as many as nine million enslaved people were exported along the trans-Saharan caravan route.[27]

Saharan triangle trade[edit]

The rise of theGhana Empire,in what is nowMali,Senegal,and southernMauritania,accompanied the increase in trans-Saharan trade. Northern economies were short of gold but at times controlled salt mines such asTaghazain the Sahara, whereas West African countries likeWangarahad plenty of gold but needed salt. Taghaza, a trading and mining outpost whereIbn Battutarecorded the buildings were made of salt, rose to preeminence in the salt trade under the hegemony of theAlmoravid Empire.[28]The salt was mined by slaves and purchased with manufactured goods from Sijilmasa.[28]Miners cut thin rectangular slabs of salt directly out of the desert floor, and caravan merchants transported them south, charging a transportation fee of almost 80% of the salt's value.[28]The salt was traded at the market ofTimbuktualmost weight for weight with gold.[28]The gold, in the form of bricks, bars, blank coins, and gold dust went toSijilmasa,from which it went out to Mediterranean ports and in which it was struck intoAlmoravid dinars.[28]

Spread of Islam[edit]

The spread of Islam to sub-Saharan African was linked to trans-Saharan trade. Islam spread via trade routes, and Africans converting to Islam increased trade and commerce which increased the trade's population.[29]

Historians give many reasons for the spread of Islam facilitating trade. Islam established common values and rules upon which trade was conducted.[29]It created a network of believers who trust each other and therefore trade with each other even if they do not personally know each other.[30]Such trade networks existed before Islam but on a much smaller scale. The spread of Islam increased the number of nodes in the network and decreased its vulnerability.[31]The use of Arabic as a common language of trade and the increase of literacy throughQuranic schools,also facilitated commerce.[32]

Muslim merchants conducting commerce also gradually spread Islam along their trade network. Social interactions with Muslim merchants led many Africans to convert to Islam, and many merchants married local women and raised their children as Muslims.[32]

Islam spread into Western Sudan by the end of the10th century,into Chad by the11th century,and intoHausalands in12thand13th centuries.By 1200, many ruling elites in Western Africa had converted to Islam, and from 1200 to 1500 saw a significant conversion to Islam in Africa.[33]

Decline of trans-Saharan trade and collapse of West African empires and kingdoms[edit]

ThePortuguese foraysalong the West African coast opened up new avenues for trade between Europe and West Africa. By the early 16th century, European trading bases, thefactoriesestablished on the coast since 1445, and trade with Europeans became of prime importance to West Africa.[vague]North Africa had declined in both political and economic importance, while the Saharan crossing remained long and treacherous. However, the major blow to trans-Saharan trade was theBattle of Tondibiof 1591–92. In a majormilitary expeditionorganized by theSaadiansultanAhmad al-Mansur,Morocco sent troops across the Sahara and attacked Timbuktu, Gao and some other important trading centres, destroying buildings and property and exiling prominent citizens. This disruption to trade led to a dramatic decline in the importance of these cities and the resulting animosity reduced trade considerably.

Although much reduced, trans-Saharan trade continued. But trade routes to the West African coast became increasingly easy, particularly after theFrench invasion of the Sahelin the 1890s and subsequent construction of railways to the interior. A railway line fromDakartoAlgiersvia the Niger bend was planned but never constructed. With the independence of nations in the region in the 1960s, the north–south routes were severed by national boundaries. National governments were hostile toTuaregnationalism and so made few efforts to maintain or support trans-Saharan trade, and theTuareg rebellionof the 1990s andAlgerian Civil Warfurther disrupted these routes, closing many.

Traditional caravan routes are largely void of camels, but the shorterAzalairoutes fromAgadeztoBilmaandTimbuktutoTaoudenniare still regularly—if lightly—used. Some members of the Tuareg still use the traditional trade routes, often traveling 2,400 km (1,500 mi) and six months out of every year by camel across the Sahara trading in salt carried from the desert interior to communities on the desert edges.[34]

The future of trans-Saharan trade[edit]

This section needs to beupdated.(July 2024) |

TheAfrican UnionandAfrican Development Banksupport theTrans-Sahara HighwayfromAlgierstoLagosviaTamanrasset,to stimulate economic development, and the latter noted an increase in traffic at the border with Chad due to exports to Algeria crossing Niger.[35]The route is paved except for a 120 mi (200 km) section in northern Niger, but border restrictions still hamper traffic. Only a fewtruckscarry trans-Saharan trade, particularlyfueland salt. Three other highways across the Sahara are proposed: for further details seeTrans-African Highways.Building the highways is difficult because of sandstorms.

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^Shillington, Kevin(1995) [1989].History of Africa(Second ed.). New York: St. Martin's Press. p.32.ISBN0-333-59957-8.

- ^Braudel, Fernand(1984).The Ghana Empire (article).Civilization and Capitalism. Vol. III.Harper & Row.Retrieved2020-05-29.

- ^Rouge, David (21 February 2007)."Saharan salt caravans ply ancient route".Reuters.

- ^"An African Pilgrim-King and a World-Traveler: Mansa Musa and Ibn Battuta".

- ^Gibb, H.A.R.; Beckingham, C.F., eds. (1994).The Travels of Ibn Baṭṭūṭa, A.D. 1325–1354.Vol. 4. London: Hakluyt Society. pp. 948–49.ISBN978-0-904180-37-4.

- ^Bovill, E.W. (1968).Golden Trade of the Moors.Oxford University Press.

- ^Shaw, Ian (2002).The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt.Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. p.61.ISBN0-500-05074-0.

- ^Aston, Barbara G.; Harrell, James A.; Shaw, Ian (2000). "Stone". In Nicholson, Paul T.; Shaw, Ian (eds.).Ancient Egyptian Materials and Technology.Cambridge. pp. 5–77 [pp. 46–47].ISBN0-521-45257-0.

{{cite book}}:CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)Also note:Aston, Barbara G. (1994).Ancient Egyptian Stone Vessels.Studien zur Archäologie und Geschichte Altägyptens. Vol. 5. Heidelberg. pp. 23–26.ISBN3-927552-12-7.{{cite book}}:CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)(See on-line posts:[1]and[2].) - ^"Trade in Ancient Egypt".World History Encyclopedia.Retrieved2020-05-29.

- ^"Ship - History of ships".Encyclopedia Britannica.Retrieved2020-05-29.

- ^Jobbins, Jenny (13–19 November 2003). "The 40 days' nightmare".Al-Ahram(664). Cairo, Egypt.

- ^Smith, Stuart Tyson."Nubia: History".University of California Santa Barbara, Department of Anthropology.RetrievedJanuary 21,2009.

- ^abcdBurr, J. Millard; Collins, Robert O. (2006).Darfur: The Long Road to Disaster.Princeton: Markus Wiener. pp. 6–7.ISBN1-55876-405-4.

- ^Vischer, Hanns (1909-03-01)."A Journey from Tripoli across the Sahara to Lake Chad".The Geographical Journal.33(3): 241–264.doi:10.2307/1776898.JSTOR1776898.

- ^abShaw, W.B.K. (1929). "Darb el Arba'in. The forty days' road".Sudan Notes and Records.12(1): 63–71.JSTOR41719405.

- ^Lydon, Ghislaine (2009), "On trans-Saharan trails",On Trans-Saharan Trails: Islamic Law, Trade Networks, and Cross-Cultural Exchange in Nineteenth-Century Western Africa,Cambridge University Press,pp. 387–400,doi:10.1017/cbo9780511575457.010,ISBN978-0-511-57545-7

- ^Shillington (1995). p. 46.

- ^Daniels, Charles (1970).The Garamantes of Southern Libya.North Harrow, Middlesex: Oleander. p.22.ISBN0-902675-04-4.

- ^David Mattingly. "The Garamantes and the Origins of Saharan Trade".Trade in the Ancient Sahara and Beyond.Cambridge University Press.pp. 27–28.

- ^abcdKeith R. Bradley. "Apuleius and the sub-Saharan slave trade".Apuleius and Antonine Rome: Historical Essays.p. 177.

- ^abcdefgAndrew Wilson. "Saharan Exports to the Roman World".Trade in the Ancient Sahara and Beyond.Cambridge University Press.pp. 192–3.

- ^abMasonen, Pekka (1997)."Trans-Saharan Trade and the West African Discovery of the Mediterranean World".In Sabour, M'hammad; Vikør, Knut S. (eds.).Ethnic Encounter and Culture Change.Bergen. pp. 116–142.ISBN1-85065-311-9.Archived fromthe originalon 1998-12-06.

{{cite book}}:CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^Lewicki, T. (1994). "The Role of the Sahara and Saharians in Relationships between North and South".UNESCO General History of Africa.Vol. 3. University of California Press.ISBN92-3-601709-6.Retrieved2021-05-06.[page needed]

- ^"Ibn Battuta's Trip:Part Twelve – Journey to West Africa (1351–1353) ".Archived fromthe originalon June 9, 2010.

- ^abcRalph A. Austen.Trans-Saharan Africa in World History.Oxford University Press.p. 31.

- ^Fage, J. D. (2001).A History of Africa(4th ed.). Routledge. p. 256.ISBN0-415-25247-4.

- ^"The impact of the slave trade on Africa".April 1998.

- ^abcdeMessier, Ronald A. (15 June 2015).The Last Civilized Place: Sijilmasa and its Saharan Destiny.University of Texas Press.ISBN978-1-4773-1135-6.

- ^abToyin Falola, Matthew M. Heaton.A History of Nigeria.pp. 32–33.

- ^Anne Haour. "What made Islamic Trade Distinctive, as Compared to Pre-Islamic Trade?".Trade in the Ancient Sahara and Beyond.Cambridge University Press.pp. 82–83.

- ^Anne Haour. "What made Islamic Trade Distinctive, as Compared to Pre-Islamic Trade?".Trade in the Ancient Sahara and Beyond.Cambridge University Press.pp. 95–96.

- ^abChristoph Strobel (11 February 2015).The Global Atlantic: 1400 to 1900.Routledge.p. 27.ISBN9781317525523.

- ^Patricia Pearson. "The World of Atlantic before the" Atlantic World "".In Toyin Falola, Kevin David Roberts (ed.).The Atlantic World, 1450-2000.Indiana University Press.pp. 10–11.

- ^"Desert Odyssey".Africa.Episode 2. 2001.National Geographic Channel.This episode follows a Tuareg tribe across the Sahara for six months by camel.

- ^"Trans-Sahara Highway:" The Niger section is almost complete and offers new economic opportunities for the population ", Alberic Houssou, Project Manager in Niger for the African Development Bank"(in English, French, Arabic, and Portuguese). African Development Bank Group. February 13, 2023.

Further reading[edit]

- Boahen, Albert Adu(1964).Britain, the Sahara and the Western Sudan 1788–1861.Oxford.

{{cite book}}:CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Bovill, Edward William (1995).The Golden Trade of the Moors.Princeton: Markus Wiener.ISBN1-55876-091-1.

- Harden, Donald (1971) [1962].The Phoenicians.Harmondsworth: Penguin.

- Shillington, Kevin,ed. (2004)."Tuareg: Takedda and trans-Saharan trade".Encyclopedia of African History.Fitzroy Dearborn.ISBN1-57958-245-1.

- Warmington, B. H. (1964) [1960].Carthage.Harmondsworth: Penguin.

- Masonen, Pekka (1997)."Trans-Saharan Trade and the West African Discovery of the Mediterranean World".In Sabour, M'hammad; Vikør, Knut S. (eds.).Ethnic Encounter and Culture Change.Bergen.ISBN1-85065-311-9.Archived fromthe originalon 1998-12-06.

{{cite book}}:CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Ross, Eric (2011). "A historical geography of the trans-Saharan trade". In Krätli, Graziano; Lydon, Ghislaine (eds.).The Trans-Saharan Book Trade: Manuscript Culture, Arabic Literacy and Intellectual History in Muslim Africa.Leiden: Brill. pp. 1–34.ISBN978-90-04-18742-9.

- "The Trans-Saharan Gold Trade 7th–14th Century".Museum of Modern Art.

- Chegrouche, Lagha (2010)."Géopolitique transsaharienne de l'énergie".Revue Géopolitique(in French). Archived fromthe originalon November 30, 2010.

- Chegrouche, Lagha (2010)."Géopolitique transsaharienne de l'énergie, le jeu et l'enjeu?".Revue de l'énergie, Etude(in French).