Trypanosoma brucei

| Trypanosoma brucei | |

|---|---|

| |

| T. b. bruceiTREU667 (Bloodstream form,phase-contrastpicture. Black bar indicates 10 µm.) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Phylum: | Euglenozoa |

| Class: | Kinetoplastea |

| Order: | Trypanosomatida |

| Family: | Trypanosomatidae |

| Genus: | Trypanosoma |

| Species: | T. brucei

|

| Binomial name | |

| Trypanosoma brucei Plimmer & Bradford, 1899

| |

| Subspecies | |

| |

Trypanosoma bruceiis a species of parasitickinetoplastidbelonging to the genusTrypanosomathat is present insub-Saharan Africa.Unlike otherprotozoanparasites that normally infect blood and tissue cells, it is exclusively extracellular and inhabits the blood plasma and body fluids.[1]It causes deadly vector-borne diseases:African trypanosomiasisor sleeping sickness in humans, andanimal trypanosomiasisornaganain cattle and horses.[2]It is aspecies complexgrouped into three subspecies:T. b. brucei,T. b. gambienseandT. b. rhodesiense.[3]The first is a parasite of non-human mammals and causesnagana,while the latter two are zoonotic infecting both humans and animals and cause African trypanosomiasis.

T. bruceiis transmitted between mammal hosts by aninsectvectorbelonging to different species oftsetse fly(Glossina). Transmission occurs by biting during the insect's blood meal. The parasites undergo complex morphological changes as they move between insect and mammal over the course oftheir life cycle.The mammalian bloodstream forms are notable for their cell surface proteins,variant surface glycoproteins,which undergo remarkableantigenic variation,enabling persistent evasion of host adaptive immunity leading to chronic infection.T. bruceiis one of only a few pathogens known to cross theblood brain barrier.[4]There is an urgent need for the development of new drug therapies, as current treatments can have severe side effects and can prove fatal to the patient.[5]

Whilst not historically regarded asT. bruceisubspecies due to their different means of transmission, clinical presentation, and loss ofkinetoplastDNA, genetic analyses reveal thatT. equiperdumandT. evansiare evolved from parasites very similar toT. b. brucei,and are thought to be members of thebruceiclade.[6]

The parasite was discovered in 1894 by SirDavid Bruce,after whom the scientific name was given in 1899.[7][8]

History and discovery

[edit]Early records

[edit]Sleeping sickness in animals were described in ancient Egyptian writings. During the Middle Ages, Arabian traders noted the prevalence of sleeping sickness among Africans and their dogs.[9]It was a major infectious diseases in southern and eastern Africa in the 19th century.[10]TheZulu Kingdom(now part of South Africa) was severely struck by the disease, which became known to the British asnagana,[2]aZuluword for to be low or depressed in spirit. In other parts of Africa, Europeans called it the "fly disease."[11][12]

John Aktins, an English naval surgeon, gave first medical description of human sleeping sickness in 1734. He attributed deaths which he called "sleepy distemper" in Guinea to the infection.[13]Another English physicianThomas Masterman Winterbottomgave clearer description of the symptoms from Sierra Leone in 1803.[14]Winterbottom described a key feature of the disease as swollen posterior cervical lymph nodes and slaves who developed such swellings were ruled unfit for trade.[13]The symptom is eponymously known as "Winterbottom's sign."[15]

Discovery of the parasite

[edit]TheRoyal Army Medical CorpsappointedDavid Bruce,who at the time was assistant professor of pathology at theArmy Medical School in Netleywith a rank of Captain in the army, in 1894 to investigate a disease known asnaganain South Africa. The disease caused severe problems among the local cattle and British Army horses.[3]On 27 October 1894, Bruce and his microbiologist-wife Mary Elizabeth Bruce (néeSteele) moved toUbombo Hill,where the disease was most prevalent.[16]

On the sixth day of investigation, Bruce identified parasites from the blood of diseased cows. He initially noted them as a kind of filaria (tiny roundworms), but by the end of the year established that the parasites were "haematozoa" (protozoan) and were the cause ofnagana.[3]It was the discovery ofTrypanosoma brucei.[17]The scientific name was created by British zoologists Henry George Plimmer andJohn Rose Bradfordin 1899 asTrypanosoma bruciidue to printer's error.[3][18]The genusTrypanosomawas already introduced by Hungarian physician David Gruby in his description ofT. sanguinis,a species he discovered in frogs in 1843.[19]

Outbreaks

[edit]In Uganda, the first case of human infection was reported in 1898.[10]It was followed by an outbreak in 1900.[20]By 1901, it became severe with death toll estimated to about 20,000.[21]More than 250,000 people died in the epidemic that lasted for two decades.[20]The disease commonly popularised as "negro lethargy."[22][23]It was not known whether the human sleeping sickness and nagana were similar or the two disease were caused by similar parasites.[24]Even the observations of Forde and Dutton did not indicate that the trypanosome was related to sleeping sickness.[25]

Sleeping Sickness Commission

[edit]TheRoyal Societyconstituted a three-member Sleeping Sickness Commission on 10 May 1902 to investigate the epidemic in Uganda.[26]The Commission comprisedGeorge Carmichael Lowfrom the LondonSchool of Hygiene and Tropical Medicineas the leader, his colleagueAldo CastellaniandCuthbert Christy,a medical officer on duty in Bombay, India.[27][28]At the time, a debate remained on the etiology, some favoured bacterial infection while some believed ashelminth infection.[29]The first investigation focussed onFilaria perstans(later renamedMansonella perstans), a small roundworm transmitted by flies, and bacteria as possible causes, only to discover that the epidemic was not related to these pathogens.[30][31]The team was described as an "ill-assorted group"[31]and a "queer lot",[32]and the expedition "a failure."[21]Low, whose conduct was described as "truculent and prone to take offence," left the Commission and Africa after three months.[33]

In February 1902, theBritish War Office,following a request from the Royal Society, appointed David Bruce to lead the second Sleeping Sickness Commission.[34]WithDavid Nunes Nabarro(from theUniversity College Hospital), Bruce and his wife joined Castellani and Christy on 16 March.[31]In November 1902, Castellani had found the trypanosomes in the cerebrospinal fluid of an infected person. He was convinced that the trypanosome was the causative parasite of sleeping sickness. Like Low, his conduct has been criticised and the Royal Society refused to publish his report. He was further infuriated when Bruce advised him not to make rash conclusion without further evidences, as there were many other parasites to consider.[26]Castellani left Africa in April and published his report as "On the discovery of a species ofTrypanosomain the cerebrospinal fluid of cases of sleeping sickness "inThe Lancet.[35]By then the Royal Society had already published the report.[36]By August 1903, Bruce and his team established that the disease was transmitted by thetsetse fly,Glossina palpalis.[37]However, Bruce did not understand the trypanosoma life cycle and believed that the parasites were simply transmitted from one person to another.[9]

Around the same time, Germany sent an expeditionary team led byRobert Kochto investigate the epidemic in Togo and East Africa. In 1909, one of the team members, Friedrich Karl Kleine discovered that the parasite had developmental stages in the tsetse flies.[9]Bruce, in the third Sleeping Sickness Commission (1908–1912) that included Albert Ernest Hamerton, H.R. Bateman andFrederick Percival Mackie,established the basic developmental cycle through which the trypanosome in tsetse fly must pass.[38][39]An open question, noted by Bruce at this stage, was how the trypanosome finds its way to the salivary glands.Muriel Robertson,[40][41]in experiments carried out between 1911 and 1912, established how ingested trypanosomes finally reach the salivary glands of the fly.

Discovery of human trypanosomes

[edit]British Colonial Surgeon Robert Michael Forde was the first to find the parasite in human. He found it from an English steamboat captain who was admitted to a hospital at Bathurst, Gambia, in 1901.[9]His report in 1902 indicates that he believed it to be a kind of filarial worm.[14]From the same person, Forde's colleague Joseph Everett Dutton identified it as a protozoan belonging to the genusTrypanosoma.[3]Knowing the distinct features, Dutton proposed a new species name in 1902:

At present then it is impossible to decide definitely as to the species, but if on further study it should be found to differ from other disease-producing trypanosomes I would suggest that it be calledTrypanosoma gambiense.[42]

Another human trypanosome (now calledT. brucei rhodesiense) was discovered by British parasitologists John William Watson Stephens and Harold Benjamin Fantham.[9]In 1910, Stephens noted in his experimental infection in rats that the trypanosome, obtained from an individual fromNorthern Rhodesia(later Zambia), was not the same asT. gambiense.The source of the parasite, an Englishman travelling in Rhodesia was found with the blood parasites in 1909, and was transported to and admitted at theRoyal Southern Hospitalin Liverpool under the care ofRonald Ross.[3]Fantham described the parasite's morphology and found that it was a different trypanosome.[43][44]

Species

[edit]T. bruceiis a species complex that includes:

- T. brucei gambiensewhich causes slow onset chronic trypanosomiasis in humans. It is most common in central and western Africa, where humans are thought to be the primaryreservoir.[45]In 1973,David Hurst Molyneuxwas the first to find infection of this strain inwildlifeanddomestic animals.[46][47]Since 2002, there are several reports showing that animals, includingcattle,are also infected.[47]It is responsible for 98% of all human African trypanosomiasis,[48]and is roughly 100% fatal.[49]

- T. brucei rhodesiensewhich causes fast onset acute trypanosomiasis in humans. A highly zoonotic parasite, it is prevalent in southern and eastern Africa, where game animals and livestock are thought to be the primary reservoir.[45][48]

- T. brucei bruceiwhich causesanimal trypanosomiasis,along with several other species ofTrypanosoma.T. b. bruceiis not infective to humans due to its susceptibility tolysisby trypanosome lytic factor-1 (TLF-1).[50][51]However, it is closely related to, and shares fundamental features with the human-infective subspecies.[52]Only rarely can theT. b. bruceiinfect a human.[53]

The subspecies cannot be distinguished from their structure as they are all identical under microscopes. Geographical location is the main distinction.[48]Molecular markers have been developed for individual identification. Serum resistance-associated (SRA) gene is used to differentiateT. b. rhodesiensefrom other subspecies.[54]TgsGPgene, found only in type 1T. b. gambienseis also a specific distinction betweenT. b. gambiensestrains.[55]

The subspecies lack many of the features commonly considered necessary to constitutemonophyly.[56]As such Lukešet al.,2022 proposes a newpolyphylybyecotype.[56]

Etymology

[edit]The genus name is derived from two Greek words: τρυπανον (trypanonortrupanon), which means "borer" or "auger", referring to the corkscrew-like movement;[57]and σῶμα (sôma), meaning "body."[58][59]The specific name is after David Bruce, who discovered the parasites in 1894.[7][8]The subspecies, the human strains, are named after the regions in Africa where they were first identified:T. brucei gambiensewas described from an Englishman in Gambia in 1901;T. brucei rhodesiensewas found from another Englishman in Northern Rhodesia in 1909.[3]

Structure

[edit]

T. bruceiis a typical unicellulareukaryotic cell,and measures 8 to 50 μm in length. It has an elongated body having a streamlined and tapered shape. Its cell membrane (called pellicle) encloses the cell organelles, including thenucleus,mitochondria,endoplasmic reticulum,Golgi apparatus,andribosomes.In addition, there is an unusual organelle called thekinetoplast,which is a complex of thousands of mitochondria.[60]The kinetoplast lies near thebasal bodywith which it is indistinguishable under microscope. From the basal body arises a singleflagellumthat run towards the anterior end. Along the body surface, the flagellum is attached to the cell membrane forming an undulating membrane. Only the tip of the flagellum is free at the anterior end.[61]The cell surface of the bloodstream form features a dense coat of variant surface glycoproteins (VSGs) which is replaced by an equally dense coat ofprocyclinswhen the parasite differentiates into theprocyclic phasein the tsetse fly midgut.[62]

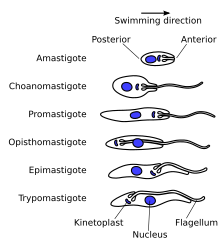

Trypanosomatidsshow several different classes of cellular organisation of which two are adopted byT. bruceiat different stages of the life cycle:[61]

- Epimastigote,which is found in tsetse fly. Its kinetoplast and basal body lie anterior to the nucleus, with a long flagellum attached along the cell body. The flagellum starts from the centre of the body.

- Trypomastigote,which is found in mammalian hosts. The kinetoplast and basal body are posterior of nucleus. The flagellum arises from the posterior end of the body.

These names are derived from theGreekmastig-meaningwhip,referring to the trypanosome's whip-like flagellum. The trypanosome flagellum has two main structures. It is made up of a typical flagellar axoneme, which lies parallel to theparaflagellar rod,[63]a lattice structure of proteins unique to thekinetoplastids,euglenoidsanddinoflagellates.[64][65]

Themicrotubulesof the flagellaraxonemelie in the normal 9+2 arrangement, orientated with the + at the anterior end and the − in the basal body. The cytoskeletal structure extends from the basal body to the kinetoplast. The flagellum is bound to the cytoskeleton of the main cell body by four specialised microtubules, which run parallel and in the same direction to the flagellar tubulin.[66][67]

The flagellar function is twofold — locomotion via oscillations along the attached flagellum and cell body in human blood stream and tsetse fly gut,[68][69]and attachment to the salivary gland epithelium of the fly during the epimastigote stage.[57][70]The flagellum propels the body in such a way that the axoneme generates the oscillation and a flagellar wave is created along the undulating membrane. As a result, the body moves in a corkscrew pattern.[57]In flagella of other organisms, the movement starts from the base towards the tip, while inT. bruceiand other trypanosomatids, the beat originates from the tip and progresses towards the base, forcing the body to move towards the direction of the tip of the flagellum.[70]

Life cycle

[edit]

T. bruceicompletes its life cycle between tsetse fly (of the genusGlossina) and mammalian hosts, including humans, cattle, horses, and wild animals. In stressful environments,T. bruceiproducesexosomescontaining thespliced leader RNAand uses theendosomal sorting complexes required for transport(ESCRT) system tosecretethem asextracellular vesicles.[71]When absorbed by other trypanosomes these EVs cause repulsive movement away from the area and so away from bad environments.[71]

In mammalian host

[edit]Infection occurs when a vector tsetse fly bites a mammalian host. The fly injects the metacyclic trypomastigotes into the skin tissue. The trypomastigotes enter thelymphatic systemand into the bloodstream. The initial trypomastigotes are short and stumpy (SS).[72]They are protected from the host's immune system by producing antigentic variation calledvariant surface glycoproteinson their body surface.[1]Once inside the bloodstream, they grow into long and slender forms (LS). Then, they multiply bybinary fission.Some of the daughter cells then become short and stumpy again.[73][74][2]Some of them remains as intermediate forms, representing a transitional stage between the long and short forms.[48]The long slender forms are able to penetrate the blood vessel endothelium and invade extravascular tissues, including thecentral nervous system(CNS)[68]and placenta in pregnant women.[75]

Sometimes, wild animals can be infected by the tsetse fly and they act as reservoirs. In these animals, they do not produce the disease, but the live parasite can be transmitted back to the normal hosts.[72]Besides preparation to be taken up and vectored to another host by a tsetse fly, transition from LS to SS in the mammal serves to prolong the host's lifespan – controllingparasitemiaaids in increasing the total transmitting duration of any particular infested host.[74][2]

In tsetse fly

[edit]Unlikeanopheline mosquitosandsandfliesthat transmit other protozoan infections in which only females are involved, both sexes of tsetse flies are blood feeders and equally transmit trypanosomes.[76]The short and stumpy trypomastigotes (SS) are taken up by tsetse flies during a blood meal.[74][2]Survival in the tsetse midgut is one reason for the particular adaptations of the SS stage.[74][2]The trypomastigotes enter the midgut of the fly where they become procyclic trypomastigotes as they replace their VSG with other protein coats calledprocyclins.[1]Because the fly faces digestive damage fromimmune factorsin thebloodmeal,it producesserpinsto suppress the infection. The serpins includingGmmSRPN3,GmmSRPN5,GmmSRPN9,and especiallyGmmSRPN10are then hijacked by the parasite to aid its own midgut infection, using them to inactivate bloodmealtrypanolyticfactors which would otherwise make the fly host inhospitable.[77]: 346

The procyclic trypomastigotes cross the peritrophic matrix, undergo slight elongation and migrate to the anterior part of the midgut as non-proliferative long mesocyclic trypomastigotes. As they reach the proventriculus, they became thinner and undergo cytoplasmic rearrangement to give rise to proliferative epimastigotes.[76]The epimastigotes divide asymmetrically to produce long and short epimastigotes. The long epimastigote cannot move to other places and simply die off byapoptosis.[78][79]The short epimastigote migrate from the proventriculus via the foregut and proboscis to thesalivary glandswhere they get attached to the salivary gland epithelium.[57]Even all the short forms do not succeed in the complete migration to the salivary glands as most of them perish on the way–only up to five may survive.[76][80]

In the salivary glands, the survivors undergo phases of reproduction. The first cycle in an equal mitosis by which a mother cell produces two similar daughter epimastigotes. They remain attach to the epithelium. This phase is the main reproduction in first-stage infection to ensure sufficient number of parasites in the salivary gland.[76]The second cycle, which usually occurs in late-stage infection, involves unequal mitosis that produces two different daughter cells from the mother epimastigote. One daughter is an epimastigote that remains non-infective and the other is a trypomastigote.[81]The trypomastigote detach from the epithelium and undergo transformation into short and stumpy trypomastigotes. The surface procyclins are replaced with VSGs and become the infective metacyclic trypomastigotes.[48]Complete development in the fly takes about 20 days.[72][73]They are injected into the mammalian host along with the saliva on biting, and are known as salivarian.[76]

In the case ofT. b. bruceiinfectingGlossina palpalis gambiensis,the parasite changes theproteomecontents of the fly's head and causes behavioral changes such as unnecessarily increased feeding frequency, which increases transmission opportunities. This is related to alteredglucosemetabolism that causes a perceived need for more calories. (The metabolic change, in turn, being due to complete absence ofglucose-6-phosphate 1-dehydrogenasein infected flies.)Monoamine neurotransmittersynthesis is also altered: production ofaromatic L-amino acid decarboxylaseinvolved indopamineandserotoninsynthesis, andα-methyldopa hypersensitive proteinwas induced. This is similar to the alterations in otherdipteranvectors' head proteomes under infection by other eukaryotic parasites of mammals.[82]

Reproduction

[edit]Binary fission

[edit]

The reproduction ofT. bruceiis unusual compared to most eukaryotes. The nuclear membrane remains intact and the chromosomes do not condense during mitosis. The basal body, unlike thecentrosomeof most eukaryotic cells, does not play a role in the organisation of the spindle and instead is involved in division of the kinetoplast. The events of reproduction are:[61]

- The basal body duplicates and both remain associated with the kinetoplast. Each basal body forms a separate flagellum.

- Kinetoplast DNA undergoes synthesis then the kinetoplast divides coupled with separation of the two basal bodies.

- Nuclear DNAundergoes synthesis while a new flagellum extends from the younger, more posterior, basal body.

- The nucleus undergoes mitosis.

- Cytokinesisprogresses from the anterior to posterior.

- Division completes withabscission.

Meiosis

[edit]In the 1980s, DNA analyses of the developmental stages ofT. bruceistarted to indicate that the trypomastigote in the tsetse fly undergoesmeiosis,i.e., a sexual reproduction stage.[83]But it is not always necessary for a complete life cycle.[84]The existence of meiosis-specific proteins was reported in 2011.[85]The haploid gametes (daughter cells produced after meiosis) were discovered in 2014. The haploid trypomastigote-like gametes can interact with each other via their flagella and undergo cell fusion (the process is called syngamy).[86][87]Thus, in addition to binary fission,T. bruceican multiply by sexual reproduction. Trypanosomes belong to the supergroupExcavataand are one of the earliest diverging lineages among eukaryotes.[88]The discovery of sexual reproduction inT. bruceisupports the hypothesis that meiosis and sexual reproduction are ancestral and ubiquitous features of eukaryotes.[89]

Infection and pathogenicity

[edit]The insect vectors forT. bruceiare different species oftsetse fly(genusGlossina). The major vectors ofT. b. gambiense,causing West African sleeping sickness, areG. palpalis,G. tachinoides,andG. fuscipes.While the principal vectors ofT. b. rhodesiense,causing East African sleeping sickness, areG. morsitans,G. pallidipes,andG. swynnertoni.Animal trypanosomiasis is transmitted by a dozen species ofGlossina.[90]

In later stages of aT. bruceiinfection of a mammalian host the parasite may migrate from the bloodstream to also infect the lymph and cerebrospinal fluids. It is under this tissue invasion that the parasites produce the sleeping sickness.[72]

In addition to the major form of transmission via the tsetse fly,T. bruceimay be transferred between mammals via bodily fluid exchange, such as by blood transfusion or sexual contact, although this is thought to be rare.[91][92]Newborn babies can be infected (vertical or congenital transmission) from infected mothers.[93]

Chemotherapy

[edit]There are four drugs generally recommended for the first-line treatment of African trypanosomiasis:suramindeveloped in 1921,pentamidinedeveloped in 1941,melarsoproldeveloped in 1949 andeflornithinedeveloped in 1990.[94][95]These drugs are not fully effective and are toxic to humans.[96]In addition, drug resistance has developed in the parasites against all the drugs.[97]The drugs are of limited application since they are effective against specific strains ofT. bruceiand the life cycle stages of the parasites. Suramin is used only for first-stage infection ofT. b. rhodesiense,pentamidine for first-stage infection ofT. b. gambiense,and eflornithine for second-stage infection ofT. b. gambiense.Melarsopol is the only drug effective against the two types of parasite in both infection stages,[98]but is highly toxic, such that 5% of treated individuals die of brain damage (reactive encephalopathy).[99]Another drug, nifurtimox, recommended forChagas disease(American trypanosomiasis), is itself a weak drug but in combination with melarsopol, it is used as the first-line medication against second-stage infection ofT. b. gambiense.[100][101]

Historically, arsenic and mercuric compounds were introduced in the early 20th century, with success particularly in animal infections.[102][103]German physicianPaul Ehrlichand his Japanese associateKiyoshi Shigadeveloped the first specific trypanocidal drug in 1904 from a dye, trypan red, which they named Trypanroth.[104]These chemical preparations were effective only at high and toxic dosages, and were not suitable for clinical use.[105]

Animal trypanosomiasis is treated with six drugs:diminazene aceturate,homidium (homidium bromide and homidium chloride),isometamidium chloride,melarsomine,quinapyramine,and suramin. They are all highly toxic to animals,[106]and drug resistance is prevalent.[107]Homidium is the first prescription anti-trypanosomal drug. It was developed as a modified compound of phenantridine, which was found in 1938 to have trypanocidal activity against the bovine parasite,T. congolense.[108]Among its products, dimidium bromide and its derivatives were first used in 1948 in animal cases in Africa,[109][110][111]and became known as homidium (or asethidium bromidein molecular biology[112]).[113][114]

Drug development

[edit]The major challenge against the human disease has been to find drugs that readily pass the blood-brain barrier. The latest drug that has come into clinical use is fexinidazol, but promising results have also been obtained with the benzoxaborole drugacoziborole(SCYX-7158). This drug is currently under evaluation as a single-dose oral treatment, which is a great advantage compared to currently used drugs. Another research field that has been extensively studied inTrypanosoma bruceiis to target its nucleotide metabolism.[115]The nucleotide metabolism studies have both led to the development of adenosine analogues looking promising in animal studies, and to the finding that downregulation of the P2 adenosine transporter is a common way to acquire partial drug resistance against the melaminophenyl arsenical anddiamidinedrug families (containing melarsoprol and pentamidine, respectively).[115]This is particularly a problem with the veterinary drug diminazene aceturate. Drug uptake and degradation are two major issues to consider to avoid drug resistance development. In the case of nucleoside analogues, they need to be taken up by the P1 nucleoside transporter (instead of P2), and they also need to be resistant against cleavage in the parasite.[116][117]

Phytochemicals.Somephytochemicalshave shown research promise against theT. b. bruceistrain.[118]Aderbaueret al.,2008 and Umaret al.,2010 findKhaya senegalensisis effectivein vitroand Ibrahimet al.,2013 and 2008in vivo(inrats).[118]Ibrahimet al.,2013 find a lower dose reducesparasitemiaby this subspecies and a higher dose is curative and prevents injury.[118]

Distribution

[edit]T. bruceiis found where its tsetse fly vectors are prevalent in continental Africa. That is to say, tropical rainforest (Af[broken anchor]), tropical monsoon (Am[broken anchor]), and tropical savannah (Aw[broken anchor]) areas of continental Africa.[61]Hence, the equatorial region of Africa is called the "sleeping sickness" belt. However, the specific type of the trypanosome differs according to geography.T. b. rhodesienseis found primarily in East Africa (Botswana, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Ethiopia, Kenya, Malawi, Tanzania, Uganda and Zimbabwe), whileT. b. gambienseis found in Central and West Africa.

Impact

[edit]T. bruceiis a major cause oflivestock diseaseinsub-Saharan Africa.[2][119]It is thus of tremendousveterinary concernand one of the greatest limitations onagriculture in Africaand the economic life of sub-Saharan Africa.[2][119]

Evolution

[edit]Trypanosoma brucei gambienseevolved from a single progenitor ~10,000 years ago.[120]It is evolving asexually and its genome shows theMeselson effect.[120]

Genetics

[edit]There are two subpopulations ofT. b. gambiensethat possesses two distinct groups that differ in genotype and phenotype. Group 2 is more akin toT. b. bruceithan group 1T. b. gambiense.[121]

AllT. b. gambienseare resistant to killing by a serum component — trypanosome lytic factor (TLF) of which there are two types: TLF-1 and TLF-2. Group 1T. b. gambienseparasites avoid uptake of the TLF particles while those of group 2 are able to either neutralize or compensate for the effects of TLF.[122]

In contrast, resistance inT. b. rhodesienseis dependent upon the expression of a serum resistance associated (SRA) gene.[123]This gene is not found inT. b. gambiense.[124]

Genome

[edit]ThegenomeofT. bruceiis made up of:[125]

- 11 pairs of largechromosomesof 1 to 6 megabase pairs.

- 3–5 intermediate chromosomes of 200 to 500 kilobase pairs.

- Around 100 minichromosomes of around 50 to 100 kilobase pairs. These may be present in multiple copies perhaploidgenome.

Mostgenesare held on the large chromosomes, with the minichromosomes carrying onlyVSGgenes. The genome has been sequenced and is available onGeneDB.[126]

The mitochondrial genome is found condensed into thekinetoplast,an unusual feature unique to the kinetoplastid protozoans. The kinetoplast and thebasal bodyof theflagellumare strongly associated via a cytoskeletal structure[127]

In 1993, a new base, ß-d-glucopyranosyloxymethyluracil (base J), was identified in the nuclear DNA ofT. brucei.[128]

VSG coat

[edit]The surface ofT. bruceiand other species of trypanosomes is covered by a dense external coat called variant surface glycoprotein (VSG).[129]VSGs are 60-kDa proteins which are densely packed (~5 x 106molecules) to form a 12–15 nm surface coat. VSG dimers make up about 90% of all cell surface proteins in trypanosomes. They also make up ~10% of total cell protein. For this reason, these proteins are highly immunogenic and an immune response raised against a specific VSG coat will rapidly kill trypanosomes expressing this variant. However, with each cell division there is a possibility that the progeny will switch expression to change the VSG that is being expressed.[129][130]

This VSG coat enables an infectingT. bruceipopulation to persistently evade the host'simmune system,allowing chronic infection. VSG is highlyimmunogenic,and animmune responseraised against a specific VSG coat rapidly kills trypanosomes expressing this variant.Antibody-mediated trypanosome killing can also be observedin vitroby acomplement-mediatedlysisassay.However, with eachcell divisionthere is a possibility that one or both of theprogenywill switch expression to change the VSG that is being expressed. The frequency of VSG switching has been measured to be approximately 0.1% per division.[131]AsT. bruceipopulations can peak at a size of 1011within a host[132]this rapid rate of switching ensures that the parasite population is typically highly diverse.[133][134]Because host immunity against a specific VSG does not develop immediately, some parasites will have switched to an antigenically distinct VSG variant, and can go on to multiply and continue the infection. The clinical effect of this cycle is successive 'waves' ofparasitemia(trypanosomes in the blood).[129]

Expression ofVSGgenes occurs through a number of mechanisms yet to be fully understood.[135]The expressed VSG can be switched either by activating a different expression site (and thus changing to express theVSGin that site), or by changing theVSGgene in the active site to a different variant. The genome contains many hundreds if not thousands ofVSGgenes, both on minichromosomes and in repeated sections ('arrays') in the interior of the chromosomes. These are transcriptionally silent, typically with omitted sections or premature stop codons, but are important in the evolution of new VSG genes. It is estimated up to 10% of theT. bruceigenome may be made up of VSG genes orpseudogenes.It is thought that any of these genes can be moved into the active site byrecombinationfor expression.[130]VSG silencing is largely due to the effects ofhistonevariants H3.V and H4.V. These histones cause changes in the three-dimensional structure of theT. bruceigenome that results in a lack of expression. VSG genes are typically located in the subtelomeric regions of the chromosomes, which makes it easier for them to be silenced when they are not being used.[136][137]It remains unproven whether the regulation of VSG switching is purely stochastic or whether environmental stimuli affect switching frequency. Switching is linked to two factors: variation in activation of individual VSG genes; and differentiation to the "short stumpy" stage - triggered by conditions of high population density - which is the nonreproductive, interhost transmission stage.[77]As of 2021[update]it also remains unexplained how this transition is timed and how the next surface protein gene is chosen.[2]These questions of antigenic variation inT. bruceiand other parasites are among the most interesting in the field ofinfection.[2]

Killing by human serum and resistance to human serum killing

[edit]Trypanosoma brucei brucei(as well as related speciesT. equiperdumandT. evansi) is not human infective because it is susceptible toinnate immune system'trypanolytic' factors present in the serum of some primates, including humans. These trypanolytic factors have been identified as two serum complexes designated trypanolytic factors (TLF-1 and −2) both of which containhaptoglobin-related protein(HPR) andapolipoprotein LI(ApoL1). TLF-1 is a member of thehigh density lipoproteinfamily of particles while TLF-2 is a related high molecular weight serum protein binding complex.[138][139]The protein components of TLF-1 are haptoglobin related protein (HPR), apolipoprotein L-1 (apoL-1) and apolipoprotein A-1 (apoA-1). These three proteins are colocalized within spherical particles containing phospholipids and cholesterol. The protein components of TLF-2 include IgM and apolipoprotein A-I.[140]

Trypanolytic factors are found only in a few species, including humans,gorillas,mandrills,baboonsandsooty mangabeys.This appears to be because haptoglobin-related protein and apolipoprotein L-1 are unique to primates. This suggests these genes originated in the primate genome25million years ago-35million years ago.[141]

Human infective subspeciesT. b. gambienseandT. b. rhodesiensehave evolved mechanisms of resisting the trypanolytic factors, described below.

ApoL1

[edit]ApoL1is a member of a six gene family, ApoL1-6, that have arisen by tandem duplication. These proteins are normally involved in host apoptosis or autophagic death and possess a Bcl-2 homology domain 3.[142]ApoL1has been identified as the toxic component involved in trypanolysis.[143]ApoLs have been subject to recent selective evolution possibly related to resistance to pathogens.[144]

The gene encodingApoL1is found on the long arm ofchromosome 22(22q12.3). Variants of this gene, termed G1 and G2, provide protection againstT. b. rhodesiense.[145]These benefits are not without their downside as a specificApoL1glomerulopathyhas been identified.[145][146]This glomerulopathy may help to explain the greater prevalence ofhypertensionin African populations.[147]

The gene encodes a protein of 383 residues, including a typical signal peptide of 12 amino acids.[148]The plasma protein is a single chain polypeptide with an apparent molecular mass of 42 kilodaltons.ApoL1has a membrane pore forming domain functionally similar to that of bacterialcolicins.[149]This domain is flanked by the membrane addressing domain and both these domains are required for parasite killing.

Within the kidney,ApoL1is found in thepodocytesin theglomeruli,the proximal tubular epithelium and the arteriolar endothelium.[150]It has a high affinity forphosphatidic acidandcardiolipinand can be induced byinterferongamma andtumor necrosis factoralpha.[151]

Hpr

[edit]Hpr is 91% identical tohaptoglobin(Hp), an abundant acute phase serum protein, which possesses a high affinity forhemoglobin(Hb). When Hb is released from erythrocytes undergoing intravascular hemolysis Hp forms a complex with the Hb and these are removed from circulation by theCD163scavenger receptor. In contrast to Hp–Hb, the Hpr–Hb complex does not bind CD163 and the Hpr serum concentration appears to be unaffected by hemolysis.[152]

Killing mechanism

[edit]The association of HPR with hemoglobin allows TLF-1 binding and uptake via the trypanosome haptoglobin-hemoglobin receptor (TbHpHbR).[153]TLF-2 enters trypanosomes independently of TbHpHbR.[153]TLF-1 uptake increases when haptoglobin level is low. TLF-1 overtakes haptoglobin and binds free hemoglobin in the serum. However the complete absence of haptoglobin is associated with a decreased killing rate by serum.[154]

The trypanosome haptoglobin-hemoglobin receptor is an elongated three a-helical bundle with a small membrane distal head.[155]This protein extends above the variant surface glycoprotein layer that surrounds the parasite.

The first step in the killing mechanism is the binding of TLF to high affinity receptors—the haptoglobin-hemoglobin receptors—that are located in the flagellar pocket of the parasite.[153][156]The bound TLF is endocytosed via coated vesicles and then trafficked to the parasitelysosomes.ApoL1is the main lethal factor in the TLFs and kills trypanosomes after insertion intoendosomal/lysosomalmembranes.[143]After ingestion by the parasite, the TLF-1 particle is trafficked to thelysosomewherein ApoL1 is activated by a pH mediated conformational change. After fusion with thelysosomethe pH drops from ~7 to ~5. This induces a conformational change in theApoL1membrane addressing domain which in turn causes a salt bridge linked hinge to open. This releasesApoL1from the HDL particle to insert in the lysosomal membrane. TheApoL1protein then creates anionic pores in the membrane which leads to depolarization of the membrane, a continuous influx ofchlorideand subsequent osmotic swelling of thelysosome.This influx in its turn leads to rupture of thelysosomeand the subsequent death of the parasite.[157]

Resistance mechanisms:T. b. gambiense

[edit]Trypanosoma brucei gambiensecauses 97% of human cases of sleeping sickness. Resistance toApoL1is principally mediated by the hydrophobicβ-sheetof theT. b. gambiensespecificglycoprotein.[158]Other factors involved in resistance appear to be a change in thecysteine proteaseactivity and TbHpHbR inactivation due to aleucinetoserinesubstitution (L210S) at codon 210.[158]This is due to athymidinetocytosinemutation at the second codon position.[159]

These mutations may have evolved due to the coexistence ofmalariawhere this parasite is found.[158]Haptoglobin levels are low in malaria because of the hemolysis that occurs with the release of themerozoitesinto the blood. The rupture of the erythrocytes results in the release of freehaeminto the blood where it is bound by haptoglobin. The haem is then removed along with the bound haptoglobin from the blood by thereticuloendothelial system.[160]

Resistance mechanisms:T. b. rhodesiense

[edit]Trypanosoma brucei rhodesienserelies on a different mechanism of resistance: the serum resistance associated protein (SRA). TheSRAgene is a truncated version of the major and variable surface antigen of the parasite, the variant surface glycoprotein.[161]However, it has little similarity (low sequence homology) with the VSG gene (<25%). SRA is an expression site associated gene inT. b. rhodesienseand is located upstream of the VSGs in the active telomeric expression site.[162]The protein is largely localized to small cytoplasmic vesicles between the flagellar pocket and the nucleus. InT. b. rhodesiensethe TLF is directed to SRA containingendosomeswhile some dispute remains as to its presence in thelysosome.[143][163]SRA binds toApoL1using a coiled–coiled interaction at the ApoL1 SRA interacting domain while within the trypanosome lysosome.[143]This interaction prevents the release of the ApoL1 protein and the subsequent lysis of the lysosome and death of the parasite.

Baboons are known to be resistant toT. b. rhodesiense.The baboon version of the ApoL1 gene differs from the human gene in a number of respects including two critical lysines near the C terminus that are necessary and sufficient to prevent baboon ApoL1 binding to SRA.[164]Experimental mutations allowing ApoL1 to be protected from neutralization by SRA have been shown capable of conferring trypanolytic activity onT. b. rhodesiense.[123]These mutations resemble those found in baboons, but also resemble natural mutations conferring protection of humans againstT. b. rhodesiensewhich are linked to kidney disease.[145]

See also

[edit]- List of parasites (human)

- Simon Gaskell,professor of chemistry and current principal ofQueen Mary, University of London,researches various forms ofmass spectrometryto determine the quantity and longevity of these proteins.

- Tryptophol,a chemical compound produced by theT. bruceiwhich induces sleep in humans[165]

References

[edit]- ^abcRomero-Meza, Gabriela; Mugnier, Monica R. (2020)."Trypanosoma brucei".Trends in Parasitology.36(6): 571–572.doi:10.1016/j.pt.2019.10.007.PMC7375462.PMID31757771.

- ^abcdefghijLuzak V, López-Escobar L, Siegel TN, Figueiredo LM (October 2021)."Cell-to-Cell Heterogeneity in Trypanosomes".Annual Review of Microbiology.75(1).Annual Reviews:107–128.doi:10.1146/annurev-micro-040821-012953.PMID34228491.S2CID235759288.

- ^abcdefgBaker JR (March 1995)."The subspecific taxonomy of Trypanosoma brucei".Parasite.2(1): 3–12.doi:10.1051/parasite/1995021003.PMID9137639.

- ^Masocha W, Kristensson K (2012)."Passage of parasites across the blood-brain barrier".Virulence.3(2): 202–212.doi:10.4161/viru.19178.PMC3396699.PMID22460639.

- ^Legros D, Ollivier G, Gastellu-Etchegorry M, Paquet C, Burri C, Jannin J, Büscher P (July 2002). "Treatment of human African trypanosomiasis--present situation and needs for research and development".The Lancet. Infectious Diseases.2(7): 437–440.doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(02)00321-3.hdl:10144/18268.PMID12127356.

- ^Gibson W (July 2007). "Resolution of the species problem in African trypanosomes".International Journal for Parasitology.37(8–9): 829–838.doi:10.1016/j.ijpara.2007.03.002.PMID17451719.

- ^abJoubert JJ, Schutte CH, Irons DJ, Fripp PJ (1993). "Ubombo and the site of David Bruce's discovery of Trypanosoma brucei".Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene.87(4): 494–495.doi:10.1016/0035-9203(93)90056-v.PMID8249096.

- ^abCook GC (1994)."Sir David Bruce's elucidation of the aetiology of nagana--exactly one hundred years ago".Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene.88(3): 257–258.doi:10.1016/0035-9203(94)90068-x.PMID7974656.

- ^abcdeSteverding D (February 2008)."The history of African trypanosomiasis".Parasites & Vectors.1(1): 3.doi:10.1186/1756-3305-1-3.PMC2270819.PMID18275594.

- ^abBerrang-Ford L, Odiit M, Maiso F, Waltner-Toews D, McDermott J (December 2006)."Sleeping sickness in Uganda: revisiting current and historical distributions".African Health Sciences.6(4): 223–231.PMC1832067.PMID17604511.

- ^Mullen GR, Durden LA (2009).Medical and Veterinary Entomology(2 ed.). Academic Press. p. 297.ISBN978-0-08-091969-0.

- ^Bruce D (1895).Preliminary Report on the Tsetse Fly Disease or Nagana, in Zululand.Durban (South Africa): Bennett & Davis. p. 1.

- ^abKennedy PG (February 2004)."Human African trypanosomiasis of the CNS: current issues and challenges".The Journal of Clinical Investigation.113(4): 496–504.doi:10.1172/JCI34802.PMC2214720.PMID14966556.

- ^abCox FE (June 2004). "History of sleeping sickness (African trypanosomiasis)".Infectious Disease Clinics of North America.18(2): 231–245.doi:10.1016/j.idc.2004.01.004.PMID15145378.

- ^Ormerod WE (October 1991). "Hypothesis: the significance of Winterbottom's sign".The Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene.94(5): 338–340.PMID1942213.

- ^Cook GC (2007).Tropical Medicine: An Illustrated History of The Pioneers.Burlington (US): Elsevier Ltd. pp. 145–156.ISBN978-0-08-055939-1.

- ^Ellis H (March 2006). "Sir David Bruce, a pioneer of tropical medicine".British Journal of Hospital Medicine.67(3): 158.doi:10.12968/hmed.2006.67.3.20624.PMID16562450.

- ^Martini E (1903). "Ueber die Entwickelung der Tsetseparasiten in Säugethieren" [Preliminary note on the morphology and distribution of the parasite found in tsetse disease].Zeitschrift für Hygiene und Infektionskrankheiten(in German).42(1): 341–351.doi:10.1007/BF02217469.S2CID12816407.

- ^Novy FG (1907). "Trypanosomes".Journal of the American Medical Association.XLVIII(1): 1–10.doi:10.1001/jama.1907.25220270001001.

- ^abFèvre EM, Coleman PG, Welburn SC, Maudlin I (April 2004)."Reanalyzing the 1900-1920 sleeping sickness epidemic in Uganda".Emerging Infectious Diseases.10(4): 567–573.doi:10.3201/eid1004.020626.PMID15200843.

- ^abCook G (2007).Tropical Medicine: An Illustrated History of The Pioneers.London: Elsevier. pp. 133–135.ISBN978-0-08-055939-1.

- ^Mott FW (December 1899)."The Changes in the Central Nervous System of Two Cases of Negro Lethargy: Sequel to Dr. Manson's Clinical Report".British Medical Journal.2(2033): 1666–1669.doi:10.1136/bmj.2.2033.1666.PMC2412509.PMID20758763.

- ^Cook GC (January 1996). "The 'Negro lethargy' in Uganda".Parasitology Today.12(1): 41.doi:10.1016/0169-4758(96)90083-6.PMID15275309.

- ^Castellani A (1903)."The history of the association ofTrypanosomawith sleeping sickness ".British Medical Journal.2(2241): 1565.doi:10.1136/bmj.2.2241.1565-a.PMC2514975.

- ^Köhler W, Köhler M (September 2002). "Zentralblatt für Bakteriologie--100 years ago: sleeping sickness--intoxication or infectious disease?".International Journal of Medical Microbiology.292(3–4): 141–147.doi:10.1078/1438-4221-00190.PMID12398205.

- ^abBoyd J (June 1973). "Sleeping sickness. The Castellani-Bruce controversy".Notes and Records of the Royal Society of London.28:93–110.doi:10.1098/rsnr.1973.0008.PMID11615538.S2CID37631020.

- ^Cook GC (January 1993)."George Carmichael Low FRCP: an underrated figure in British tropical medicine".Journal of the Royal College of Physicians of London.27(1): 81–82.PMC5396591.PMID8426352.

- ^Cook GC (1993). "Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene meeting at Manson House, London, 10 December 1992. George Carmichael Low FRCP: twelfth president of the Society and underrated pioneer of tropical medicine".Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene.87(4): 355–360.doi:10.1016/0035-9203(93)90002-8.PMID8249057.

- ^Amaral I (December 2012)."Bacteria or parasite? the controversy over the etiology of sleeping sickness and the Portuguese participation, 1898-1904".Historia, Ciencias, Saude--Manguinhos.19(4): 1275–1300.doi:10.1590/s0104-59702012005000004.PMID23184240.

- ^Cook GC (May 2012). "Patrick Manson (1844-1922) FRS: Filaria (Mansonella) perstans and sleeping sickness (African trypanosomiasis)".Journal of Medical Biography.20(2): 69.doi:10.1258/jmb.2010.010051.PMID22791871.S2CID33661530.

- ^abcLumsden WH (August 1974)."Some episodes in the history of African trypanosomiasis".Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine.67(8): 789–796.doi:10.1177/003591577406700846.PMC1645813.PMID4607392.

- ^Wiggins CA (November 1960). "Early days in East Africa and Uganda".East African Medical Journal.37:699–708 contd.PMID13785176.

- ^Davies JN (March 1962). "The cause of sleeping-sickness? Entebbe 1902-03. I".East African Medical Journal.39:81–99.PMID13883839.

- ^J.R. B. (1932). "Sir David Bruce. 1855-1931".Obituary Notices of Fellows of the Royal Society.1(1): 79–85.doi:10.1098/rsbm.1932.0017.ISSN1479-571X.JSTOR768965.

- ^Castellani A (1903). "On the discovery of a species of trypanosoma in the cerebrospinal fluid of cases of sleeping sickness".The Lancet.161(4164): 1735–1736.doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(01)70338-8.

- ^Castellani A (1903). "On the discovery of a species oftrypanosomain the cerebrospinal fluid of cases of sleeping sickness ".Proceedings of the Royal Society of London.71(467–476): 501–508.doi:10.1098/rspl.1902.0134.S2CID59110369.

- ^Welburn SC, Maudlin I, Simarro PP (December 2009)."Controlling sleeping sickness - a review"(PDF).Parasitology.136(14): 1943–1949.doi:10.1017/S0031182009006416.PMID19691861.S2CID41052902.

- ^Bruce D, Hamerton AE, Bateman HR, Mackie FP (1909). "The development ofTrypanosoma gambienseinGlossina palpalis".Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series B.81(550): 405–414.doi:10.1098/rspb.1909.0041.

- ^Bruce D, Hamerton AE, Bateman HR, Mackie FP (1911)."Further researches on the development ofTrypanosoma gambienseinGlossina palpalis".Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series B.83(567): 513–527.doi:10.1098/rspb.1911.0034.

- ^Miles, A. A. (July 1976)."Muriel Robertson, 1883–1973".Microbiology.95(1): 1–8.doi:10.1099/00221287-95-1-1.ISSN1465-2080.PMID784900.

- ^"Further researches on the development of trypanosoma gambiense in glossina palpalis".Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Containing Papers of a Biological Character.83(567): 513–527. 31 May 1911.doi:10.1098/rspb.1911.0034.ISSN0950-1193.

- ^Dutton JE (1902)."Preliminary note upon a trypanosome occurring in the blood of man".Wellcome Collection.Retrieved21 March2021.

- ^Stephens JW, Fantham HB, Ross R (1910)."On the peculiar morphology of a trypanosome from a case of sleeping sickness and the possibility of its being a new species (T. rhodesiense) ".Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series B.83(561): 28–33.doi:10.1098/rspb.1910.0064.

- ^Stephens JW, Fantham HB (1910)."On the Peculiar Morphology of a Trypanosome From a Case of Sleeping Sickness and the Possibility of Its Being a New Species (T. Rhodesiense) ".Annals of Tropical Medicine & Parasitology.4(3): 343–350.doi:10.1080/00034983.1910.11685723.

- ^abBarrett MP, Burchmore RJ, Stich A, Lazzari JO, Frasch AC, Cazzulo JJ, Krishna S (November 2003). "The trypanosomiases".Lancet.362(9394): 1469–1480.doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14694-6.PMID14602444.S2CID7917540.

- ^Molyneux DH(1973). "Animal reservoirs and Gambian trypanosomiasis".Annales de la Société Belge de Médecine Tropicale.53(6): 605–618.PMID4204667.

- ^abBüscher P, Cecchi G, Jamonneau V, Priotto G (November 2017). "Human African trypanosomiasis".Lancet.390(10110): 2397–2409.doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31510-6.PMID28673422.S2CID4853616.

- ^abcdeFranco, Jose R; Simarro, Pere P; Diarra, Abdoulaye; Jannin, Jean G (2014)."Epidemiology of human African trypanosomiasis".Clinical Epidemiology.6:257–275.doi:10.2147/CLEP.S39728.ISSN1179-1349.PMC4130665.PMID25125985.

- ^Jamonneau, Vincent; Ilboudo, Hamidou; Kaboré, Jacques; Kaba, Dramane; Koffi, Mathurin; Solano, Philippe; Garcia, André; Courtin, David; Laveissière, Claude; Lingue, Kouakou; Büscher, Philippe; Bucheton, Bruno (2012)."Untreated human infections by Trypanosoma brucei gambiense are not 100% fatal".PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases.6(6): e1691.doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0001691.ISSN1935-2735.PMC3373650.PMID22720107.

- ^Stephens NA, Kieft R, Macleod A, Hajduk SL (December 2012)."Trypanosome resistance to human innate immunity: targeting Achilles' heel".Trends in Parasitology.28(12): 539–545.doi:10.1016/j.pt.2012.09.002.PMC4687903.PMID23059119.

- ^Rifkin MR (August 1984). "Trypanosoma brucei: biochemical and morphological studies of cytotoxicity caused by normal human serum".Experimental Parasitology.58(1).Elsevier:81–93.doi:10.1016/0014-4894(84)90023-7.PMID6745390.

- ^Balmer O, Beadell JS, Gibson W, Caccone A (February 2011)."Phylogeography and taxonomy of Trypanosoma brucei".PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases.5(2): e961.doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0000961.PMC3035665.PMID21347445.

- ^Deborggraeve S, Koffi M, Jamonneau V, Bonsu FA, Queyson R, Simarro PP, et al. (August 2008). "Molecular analysis of archived blood slides reveals an atypical human Trypanosoma infection".Diagnostic Microbiology and Infectious Disease.61(4): 428–433.doi:10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2008.03.006.PMID18455900.

- ^Radwanska, Magdalena; Chamekh, Mustapha; Vanhamme, Luc; Claes, Filip; Magez, Stefan; Magnus, Eddy; de Baetselier, Patrick; Büscher, Philippe; Pays, Etienne (2002)."The serum resistance-associated gene as a diagnostic tool for the detection of Trypanosoma brucei rhodesiense".The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene.67(6): 684–690.doi:10.4269/ajtmh.2002.67.684.ISSN0002-9637.PMID12518862.S2CID3232109.

- ^Felu, Cecile; Pasture, Julie; Pays, Etienne; Pérez-Morga, David (2007)."Diagnostic potential of a conserved genomic rearrangement in the Trypanosoma brucei gambiense-specific TGSGP locus".The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene.76(5): 922–929.doi:10.4269/ajtmh.2007.76.922.ISSN0002-9637.PMID17488917.

- ^abLukeš, Julius; Kachale, Ambar; Votýpka, Jan; Butenko, Anzhelika; Field, Mark (2022). "African trypanosome strategies for conquering new hosts and territories: the end of monophyly?".Trends in Parasitology.38(9).Cell Press:724–736.doi:10.1016/j.pt.2022.05.011.ISSN1471-4922.PMID35680542.S2CID249448815.

- ^abcdKrüger T, Schuster S, Engstler M (December 2018). "Beyond Blood: African Trypanosomes on the Move".Trends in Parasitology.34(12): 1056–1067.doi:10.1016/j.pt.2018.08.002.PMID30181072.S2CID52154369.

- ^"Etymologia: Trypanosoma".Emerging Infectious Diseases.12(9): 1473. 2006.doi:10.3201/eid1209.ET1209.ISSN1080-6040.PMC3293449.

- ^Morriswood, Brooke (2015)."Form, Fabric, and Function of a Flagellum-Associated Cytoskeletal Structure".Cells.4(4): 726–747.doi:10.3390/cells4040726.ISSN2073-4409.PMC4695855.PMID26540076.

- ^Amodeo S, Jakob M, Ochsenreiter T (April 2018)."Characterization of the novel mitochondrial genome replication factor MiRF172 inTrypanosoma brucei".Journal of Cell Science.131(8).The Company of Biologists:jcs211730.doi:10.1242/jcs.211730.PMC5963845.PMID29626111.

- ^abcd"African animal trypanosomes".Food and Agricultural Organization.Retrieved28 January2016.

- ^Romero-Meza G, Mugnier MR (June 2020)."Trypanosoma brucei".Trends in Parasitology.36(6): 571–572.doi:10.1016/j.pt.2019.10.007.PMC7375462.PMID31757771.

- ^Koyfman AY, Schmid MF, Gheiratmand L, Fu CJ, Khant HA, Huang D, et al. (July 2011)."Structure of Trypanosoma brucei flagellum accounts for its bihelical motion".Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America.108(27): 11105–11108.Bibcode:2011PNAS..10811105K.doi:10.1073/pnas.1103634108.PMC3131312.PMID21690369.

- ^v (1988). "The paraflagellar rod: a structure in search of a function".Biology of the Cell.63(2): 169–181.doi:10.1016/0248-4900(88)90056-1.ISSN0248-4900.S2CID86009836.

- ^Bastin P, Matthews KR, Gull K (August 1996). "The paraflagellar rod of kinetoplastida: solved and unsolved questions".Parasitology Today.12(8): 302–307.doi:10.1016/0169-4758(96)10031-4.PMID15275181.

- ^Sunter JD, Gull K (April 2016)."The Flagellum Attachment Zone: 'The Cellular Ruler' of Trypanosome Morphology".Trends in Parasitology.32(4).Cell Press:309–324.doi:10.1016/j.pt.2015.12.010.PMC4827413.PMID26776656.S2CID1080165.

- ^Woods A, Sherwin T, Sasse R, MacRae TH, Baines AJ, Gull K (July 1989). "Definition of individual components within the cytoskeleton of Trypanosoma brucei by a library of monoclonal antibodies".Journal of Cell Science.93 ( Pt 3) (3): 491–500.doi:10.1242/jcs.93.3.491.PMID2606940.

- ^abLangousis G, Hill KL (July 2014)."Motility and more: the flagellum of Trypanosoma brucei".Nature Reviews. Microbiology.12(7): 505–518.doi:10.1038/nrmicro3274.PMC4278896.PMID24931043.

- ^Halliday C, de Castro-Neto A, Alcantara CL, Cunha-E-Silva NL, Vaughan S, Sunter JD (April 2021). "Trypanosomatid Flagellar Pocket from Structure to Function".Trends in Parasitology.37(4): 317–329.doi:10.1016/j.pt.2020.11.005.PMID33308952.S2CID229179306.

- ^abRalston KS, Kabututu ZP, Melehani JH, Oberholzer M, Hill KL (2009)."The Trypanosoma brucei flagellum: moving parasites in new directions".Annual Review of Microbiology.63:335–362.doi:10.1146/annurev.micro.091208.073353.PMC3821760.PMID19575562.

- ^abJuan T, Fürthauer M (February 2018). "Biogenesis and function of ESCRT-dependent extracellular vesicles".Seminars in Cell & Developmental Biology.74.Elsevier:66–77.doi:10.1016/j.semcdb.2017.08.022.PMID28807885.

- ^abcdChatterjee KD (2009).Parasitology (Protozoology and Helminthology) in relation to clinical medicine(13 ed.). New Delhi: CBC Publishers. pp. 56–57.ISBN978-8-12-39-1810-5.

- ^ab"Parasites - African Trypanosomiasis (also known as Sleeping Sickness)".Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.Retrieved29 January2016.

- ^abcdSeed JR, Wenck MA (June 2003)."Role of the long slender to short stumpy transition in the life cycle of the african trypanosomes".Kinetoplastid Biology and Disease.2(1).BioMed Central:3.doi:10.1186/1475-9292-2-3.PMC165594.PMID12844365.

- ^McClure, Elizabeth M.; Goldenberg, Robert L. (2009)."Infection and stillbirth".Seminars in Fetal & Neonatal Medicine.14(4): 182–189.doi:10.1016/j.siny.2009.02.003.ISSN1878-0946.PMC3962114.PMID19285457.

- ^abcdeRotureau, Brice; Van Den Abbeele, Jan (2013)."Through the dark continent: African trypanosome development in the tsetse fly".Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology.3:53.doi:10.3389/fcimb.2013.00053.ISSN2235-2988.PMC3776139.PMID24066283.

- ^abMideo N, Acosta-Serrano A, Aebischer T, Brown MJ, Fenton A, Friman VP, et al. (January 2013)."Life in cells, hosts, and vectors: parasite evolution across scales"(PDF).Infection, Genetics and Evolution.13:344–347.doi:10.1016/j.meegid.2012.03.016.PMID22465537.(VPFORCID0000-0002-1592-157X).

- ^Proto, William R.; Coombs, Graham H.; Mottram, Jeremy C. (2013). "Cell death in parasitic protozoa: regulated or incidental?".Nature Reviews. Microbiology.11(1): 58–66.doi:10.1038/nrmicro2929.ISSN1740-1534.PMID23202528.S2CID1633550.

- ^Van Den Abbeele, J.; Claes, Y.; van Bockstaele, D.; Le Ray, D.; Coosemans, M. (1999). "Trypanosoma brucei spp. development in the tsetse fly: characterization of the post-mesocyclic stages in the foregut and proboscis".Parasitology.118 ( Pt 5) (5): 469–478.doi:10.1017/s0031182099004217.ISSN0031-1820.PMID10363280.S2CID32217938.

- ^Oberle, Michael; Balmer, Oliver; Brun, Reto; Roditi, Isabel (2010)."Bottlenecks and the maintenance of minor genotypes during the life cycle of Trypanosoma brucei".PLOS Pathogens.6(7): e1001023.doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1001023.ISSN1553-7374.PMC2912391.PMID20686656.

- ^Rotureau, Brice; Subota, Ines; Buisson, Johanna; Bastin, Philippe (2012)."A new asymmetric division contributes to the continuous production of infective trypanosomes in the tsetse fly".Development.139(10): 1842–1850.doi:10.1242/dev.072611.ISSN1477-9129.PMID22491946.S2CID7068417.

- ^Lefèvre T, Thomas F, Ravel S, Patrel D, Renault L, Le Bourligu L, et al. (December 2007). "Trypanosoma brucei brucei induces alteration in the head proteome of the tsetse fly vector Glossina palpalis gambiensis".Insect Molecular Biology.16(6).Royal Entomological Society(Wiley): 651–660.doi:10.1111/j.1365-2583.2007.00761.x.PMID18092995.S2CID3134104.

- ^Zampetti-Bosseler F, Schweizer J, Pays E, Jenni L, Steinert M (August 1986)."Evidence for haploidy in metacyclic forms of Trypanosoma brucei".Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America.83(16): 6063–6064.Bibcode:1986PNAS...83.6063Z.doi:10.1073/pnas.83.16.6063.PMC386438.PMID3461475.

- ^Jenni L (1990)."Sexual stages in trypanosomes and implications".Annales de Parasitologie Humaine et Comparée.65(Suppl 1): 19–21.doi:10.1051/parasite/1990651019.PMID2264676.

- ^Peacock L, Ferris V, Sharma R, Sunter J, Bailey M, Carrington M, Gibson W (March 2011)."Identification of the meiotic life cycle stage of Trypanosoma brucei in the tsetse fly".Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America.108(9): 3671–3676.Bibcode:2011PNAS..108.3671P.doi:10.1073/pnas.1019423108.PMC3048101.PMID21321215.

- ^Peacock L, Bailey M, Carrington M, Gibson W (January 2014)."Meiosis and haploid gametes in the pathogen Trypanosoma brucei".Current Biology.24(2): 181–186.Bibcode:2014CBio...24..181P.doi:10.1016/j.cub.2013.11.044.PMC3928991.PMID24388851.

- ^Peacock L, Ferris V, Bailey M, Gibson W (February 2014)."Mating compatibility in the parasitic protist Trypanosoma brucei".Parasites & Vectors.7(1): 78.doi:10.1186/1756-3305-7-78.PMC3936861.PMID24559099.

- ^Hampl V, Hug L, Leigh JW, Dacks JB, Lang BF, Simpson AG, Roger AJ (March 2009)."Phylogenomic analyses support the monophyly of Excavata and resolve relationships among eukaryotic" supergroups "".Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America.106(10): 3859–3864.Bibcode:2009PNAS..106.3859H.doi:10.1073/pnas.0807880106.PMC2656170.PMID19237557.

- ^Malik SB, Pightling AW, Stefaniak LM, Schurko AM, Logsdon JM (August 2007)."An expanded inventory of conserved meiotic genes provides evidence for sex in Trichomonas vaginalis".PLOS ONE.3(8): e2879.Bibcode:2008PLoSO...3.2879M.doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0002879.PMC2488364.PMID18663385.

- ^Krisnky WL (2009)."Tsetse fly (Glossinidae)".In Mullen GR, Durden L (eds.).Medical and Veterinary Entomology(2 ed.). Amsterdam: Elsevier. p. 296.ISBN978-0-0-80-91969-0.

- ^"African Trypanosomes: epidemiology and risk factors".Centers for Disease Control. 2 May 2017.

- ^Rocha G, Martins A, Gama G, Brandão F, Atouguia J (January 2004). "Possible cases of sexual and congenital transmission of sleeping sickness".Lancet.363(9404): 247.doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(03)15345-7.PMID14738812.S2CID5311361.

- ^Lindner, Andreas K.; Priotto, Gerardo (2010)."The unknown risk of vertical transmission in sleeping sickness--a literature review".PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases.4(12): e783.doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0000783.ISSN1935-2735.PMC3006128.PMID21200416.

- ^Nok AJ (May 2003). "Arsenicals (melarsoprol), pentamidine and suramin in the treatment of human African trypanosomiasis".Parasitology Research.90(1): 71–79.doi:10.1007/s00436-002-0799-9.PMID12743807.S2CID35019516.

- ^Burri C, Brun R (June 2003). "Eflornithine for the treatment of human African trypanosomiasis".Parasitology Research.90 Supp 1: S49–S52.doi:10.1007/s00436-002-0766-5.PMID12811548.S2CID35509112.

- ^Docampo R, Moreno SN (June 2003). "Current chemotherapy of human African trypanosomiasis".Parasitology Research.90 Supp 1: S10–S13.doi:10.1007/s00436-002-0752-y.PMID12811544.S2CID21917230.

- ^Barrett MP, Vincent IM, Burchmore RJ, Kazibwe AJ, Matovu E (September 2011). "Drug resistance in human African trypanosomiasis".Future Microbiology.6(9): 1037–1047.doi:10.2217/fmb.11.88.PMID21958143.

- ^Babokhov P, Sanyaolu AO, Oyibo WA, Fagbenro-Beyioku AF, Iriemenam NC (July 2013)."A current analysis of chemotherapy strategies for the treatment of human African trypanosomiasis".Pathogens and Global Health.107(5): 242–252.doi:10.1179/2047773213Y.0000000105.PMC4001453.PMID23916333.

- ^Kennedy PG (February 2013). "Clinical features, diagnosis, and treatment of human African trypanosomiasis (sleeping sickness)".The Lancet. Neurology.12(2): 186–194.doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(12)70296-X.PMID23260189.S2CID8688394.

- ^Lutje V, Seixas J, Kennedy A (June 2013)."Chemotherapy for second-stage human African trypanosomiasis".The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews.2013(6): CD006201.doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006201.pub3.PMC6532745.PMID23807762.

- ^Bottieau E, Clerinx J (March 2019). "Human African Trypanosomiasis: Progress and Stagnation".Infectious Disease Clinics of North America.33(1): 61–77.doi:10.1016/j.idc.2018.10.003.PMID30712768.S2CID73432597.

- ^Thomas HW (May 1905)."Some Experiments in the Treatment of Trypanosomiasis".British Medical Journal.1(2317): 1140–1143.doi:10.1136/bmj.1.2317.1140.PMC2320665.PMID20762118.

- ^Moore B, Nierenstein M, Todd JL (1907)."On the Treatment of Trypanosomiasis by Atoxyl (an Organic Arsenical Compound), followed by a Mercuric Salt (Mercuric Chloride) being a Bio-Chemical Study of the Reaction of a Parasitic Protozoon to Different Chemical Reagents at Different Stages of its Life History".The Biochemical Journal.2(5–6): 300–324.doi:10.1042/bj0020300.PMC1276215.PMID16742071.

- ^Wenyon CM (April 1907)."Action of the Colours of Benzidine on Mice Infected with Trypanosoma dimorphon".The Journal of Hygiene.7(2): 273–290.doi:10.1017/s0022172400033295.PMC2236235.PMID20474312.

- ^Nocht B (1935)."Present state of knowledge of chemotherapy".Chinese Medical Journal.49(5): 479–489.

- ^Giordani F, Morrison LJ, Rowan TG, DE Koning HP, Barrett MP (December 2016)."The animal trypanosomiases and their chemotherapy: a review".Parasitology.143(14): 1862–1889.doi:10.1017/S0031182016001268.PMC5142301.PMID27719692.

- ^Kasozi KI, MacLeod ET, Waiswa C, Mahero M, Ntulume I, Welburn SC (August 2022)."Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis on Knowledge Attitude and Practices on African Animal Trypanocide Resistance".Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease.7(9): 205.doi:10.3390/tropicalmed7090205.PMC9503918.PMID36136616.

- ^Walls LP (1947)."The chemotherapy of phenanthridine compounds".Journal of the Society of Chemical Industry.66(6): 182–187.doi:10.1002/jctb.5000660604.

- ^Wilson SG (April 1948). "Further observations on the curative value of dimidium bromide in Trypanosoma congolense infections in bovines in Uganda".The Journal of Comparative Pathology and Therapeutics.58(2): 94–106.doi:10.1016/s0368-1742(48)80008-1.PMID18861668.

- ^Wilson SG (1948). "Further Observations on the Curative Value of Dimidium Bromide (Phenanthridinium 1553) in Trypanosoma Congolense Infections in Bovines in Uganda".Journal of Comparative Pathology and Therapeutics.58(2): 94–106.doi:10.1016/S0368-1742(48)80008-1.PMID18861668.

- ^Carmichael J (April 1950). "Dimidium bromide or phenanthridinium 1553; a note on the present position".The Veterinary Record.62(17): 257.doi:10.1136/vr.62.17.257-a(inactive 1 November 2024).PMID15418753.S2CID33016283.

{{cite journal}}:CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of November 2024 (link) - ^Lai JS, Herr W (August 1992)."Ethidium bromide provides a simple tool for identifying genuine DNA-independent protein associations".Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America.89(15): 6958–6962.Bibcode:1992PNAS...89.6958L.doi:10.1073/pnas.89.15.6958.PMC49624.PMID1495986.

- ^Elslager EF, Thompson PE (1962). "Parasite Chemotherapy".Annual Review of Pharmacology.2(1): 193–214.doi:10.1146/annurev.pa.02.040162.001205.ISSN0066-4251.

- ^Kasozi KI, MacLeod ET, Ntulume I, Welburn SC (2022)."An Update on African Trypanocide Pharmaceutics and Resistance".Frontiers in Veterinary Science.9:828111.doi:10.3389/fvets.2022.828111.PMC8959112.PMID35356785.

- ^abHofer A (2022)."Targeting the nucleotide metabolism of Trypanosoma brucei and other trypanosomatids".FEMS Microbiology Reviews.47(3): fuad020.doi:10.1093/femsre/fuad020.PMC10208901.PMID37156497.

- ^Vodnala M, Ranjbarian F, Pavlova A, de Koning HP, Hofer A (2016)."Methylthioadenosine Phosphorylase Protects the Parasite from the Antitrypanosomal Effect of Deoxyadenosine: implications for the pharmacology of adenosine antimetabolites".Journal of Biological Chemistry.291(22): 11717–26.doi:10.1074/jbc.M116.715615.PMC4882440.PMID27036940.

- ^Ranjbarian F, Vodnala M, Alzahrani KJ, Ebiloma GU, de Koning HP, Hofer A (2016)."9-(2'-Deoxy-2'-Fluoro-β-d-Arabinofuranosyl) Adenine Is a Potent Antitrypanosomal Adenosine Analogue That Circumvents Transport-Related Drug Resistance".Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy.61(6): e02719-16.doi:10.1128/AAC.02719-16.PMC5444181.PMID28373184.

- ^abcIbrahim MA, Mohammed A, Isah MB, Aliyu AB (May 2014). "Anti-trypanosomal activity of African medicinal plants: a review update".Journal of Ethnopharmacology.154(1).International Society of Ethnopharmacology(Elsevier): 26–54.doi:10.1016/j.jep.2014.04.012.PMID24742753.

- ^abAuty H, Torr SJ, Michoel T, Jayaraman S, Morrison LJ (August 2015)."Cattle trypanosomosis: the diversity of trypanosomes and implications for disease epidemiology and control".Revue Scientifique et Technique.34(2). O.I.E (World Organisation for Animal Health): 587–598.doi:10.20506/rst.34.2.2382.PMID26601459.S2CID42700199.

- ^abWeir W, Capewell P, Foth B, Clucas C, Pountain A, Steketee P, et al. (January 2016)."Population genomics reveals the origin and asexual evolution of human infective trypanosomes".eLife.5:e11473.doi:10.7554/eLife.11473.PMC4739771.PMID26809473.

- ^Paindavoine P, Pays E, Laurent M, Geltmeyer Y, Le Ray D, Mehlitz D, Steinert M (February 1986). "The use of DNA hybridization and numerical taxonomy in determining relationships between Trypanosoma brucei stocks and subspecies".Parasitology.92(Pt 1): 31–50.doi:10.1017/S0031182000063435.PMID3960593.S2CID33529173.

- ^Capewell P, Veitch NJ, Turner CM, Raper J, Berriman M, Hajduk SL, MacLeod A (September 2011)."Differences between Trypanosoma brucei gambiense groups 1 and 2 in their resistance to killing by trypanolytic factor 1".PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases.5(9): e1287.doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0001287.PMC3167774.PMID21909441.

- ^abLecordier L, Vanhollebeke B, Poelvoorde P, Tebabi P, Paturiaux-Hanocq F, Andris F, et al. (December 2009). Mansfield JM (ed.)."C-terminal mutants of apolipoprotein L-I efficiently kill both Trypanosoma brucei brucei and Trypanosoma brucei rhodesiense".PLOS Pathogens.5(12): e1000685.doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1000685.PMC2778949.PMID19997494.

- ^De Greef C, Imberechts H, Matthyssens G, Van Meirvenne N, Hamers R (September 1989). "A gene expressed only in serum-resistant variants of Trypanosoma brucei rhodesiense".Molecular and Biochemical Parasitology.36(2): 169–176.doi:10.1016/0166-6851(89)90189-8.PMID2528066.

- ^Ogbadoyi E, Ersfeld K, Robinson D, Sherwin T, Gull K (March 2000). "Architecture of the Trypanosoma brucei nucleus during interphase and mitosis".Chromosoma.108(8): 501–513.doi:10.1007/s004120050402.PMID10794572.S2CID3850480.

- ^Jackson AP, Sanders M, Berry A, McQuillan J, Aslett MA, Quail MA, et al. (April 2010)."The genome sequence of Trypanosoma brucei gambiense, causative agent of chronic human african trypanosomiasis".PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases.4(4): e658.doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0000658.PMC2854126.PMID20404998.

- ^Ogbadoyi EO, Robinson DR, Gull K (May 2003)."A high-order trans-membrane structural linkage is responsible for mitochondrial genome positioning and segregation by flagellar basal bodies in trypanosomes".Molecular Biology of the Cell.14(5): 1769–1779.doi:10.1091/mbc.E02-08-0525.PMC165075.PMID12802053.

- ^Borst P, Sabatini R (2008). "Base J: discovery, biosynthesis, and possible functions".Annual Review of Microbiology.62:235–251.doi:10.1146/annurev.micro.62.081307.162750.PMID18729733.

- ^abcBarry JD, McCulloch R (2001). "Antigenic variation in trypanosomes: enhanced phenotypic variation in a eukaryotic parasite".Advances in Parasitology Volume 49.pp. 1–70.doi:10.1016/S0065-308X(01)49037-3.ISBN978-0-12-031749-3.PMID11461029.

- ^abMorrison LJ, Marcello L, McCulloch R (December 2009)."Antigenic variation in the African trypanosome: molecular mechanisms and phenotypic complexity".Cellular Microbiology.11(12): 1724–1734.doi:10.1111/j.1462-5822.2009.01383.x.PMID19751359.S2CID26552797.

- ^Turner CM (August 1997). "The rate of antigenic variation in fly-transmitted and syringe-passaged infections of Trypanosoma brucei".FEMS Microbiology Letters.153(1): 227–231.doi:10.1111/j.1574-6968.1997.tb10486.x.PMID9252591.

- ^Barry JD, Hall JP, Plenderleith L (September 2012)."Genome hyperevolution and the success of a parasite".Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences.1267(1): 11–17.Bibcode:2012NYASA1267...11B.doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.2012.06654.x.PMC3467770.PMID22954210.

- ^Hall JP, Wang H, Barry JD (11 July 2013)."Mosaic VSGs and the scale of Trypanosoma brucei antigenic variation".PLOS Pathogens.9(7): e1003502.doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1003502.PMC3708902.PMID23853603.

- ^Mugnier MR, Cross GA, Papavasiliou FN (March 2015)."The in vivo dynamics of antigenic variation in Trypanosoma brucei".Science.347(6229): 1470–1473.Bibcode:2015Sci...347.1470M.doi:10.1126/science.aaa4502.PMC4514441.PMID25814582.

- ^Pays E (November 2005). "Regulation of antigen gene expression in Trypanosoma brucei".Trends in Parasitology.21(11): 517–520.doi:10.1016/j.pt.2005.08.016.PMID16126458.

- ^Rudenko G (26 October 2018)."Faculty of 1000 evaluation for Genome organization and DNA accessibility control antigenic variation in trypanosomes".F1000.doi:10.3410/f.734240334.793552268.

- ^Müller LS, Cosentino RO, Förstner KU, Guizetti J, Wedel C, Kaplan N, et al. (November 2018)."Genome organization and DNA accessibility control antigenic variation in trypanosomes".Nature.563(7729).Nature Research:121–125.Bibcode:2018Natur.563..121M.doi:10.1038/s41586-018-0619-8.PMC6784898.PMID30333624.

- ^Hajduk SL, Moore DR, Vasudevacharya J, Siqueira H, Torri AF, Tytler EM, Esko JD (March 1989)."Lysis of Trypanosoma brucei by a toxic subspecies of human high density lipoprotein".The Journal of Biological Chemistry.264(9): 5210–5217.doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(18)83720-6.PMID2494183.

- ^Raper J, Fung R, Ghiso J, Nussenzweig V, Tomlinson S (April 1999)."Characterization of a novel trypanosome lytic factor from human serum".Infection and Immunity.67(4): 1910–1916.doi:10.1128/IAI.67.4.1910-1916.1999.PMC96545.PMID10085035.

- ^Vanhollebeke B, Pays E (May 2010)."The trypanolytic factor of human serum: many ways to enter the parasite, a single way to kill"(PDF).Molecular Microbiology.76(4): 806–814.doi:10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07156.x.PMID20398209.S2CID7740199.

- ^Lugli EB, Pouliot M, Portela Md, Loomis MR, Raper J (November 2004). "Characterization of primate trypanosome lytic factors".Molecular and Biochemical Parasitology.138(1): 9–20.doi:10.1016/j.molbiopara.2004.07.004.PMID15500911.

- ^Vanhollebeke B, Pays E (September 2006)."The function of apolipoproteins L".Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences.63(17): 1937–1944.doi:10.1007/s00018-006-6091-x.PMC11136045.PMID16847577.S2CID12713960.

- ^abcdVanhamme L, Paturiaux-Hanocq F, Poelvoorde P, Nolan DP, Lins L, Van Den Abbeele J, et al. (March 2003). "Apolipoprotein L-I is the trypanosome lytic factor of human serum".Nature.422(6927): 83–87.Bibcode:2003Natur.422...83V.doi:10.1038/nature01461.PMID12621437.S2CID4310920.

- ^Smith EE, Malik HS (May 2009)."The apolipoprotein L family of programmed cell death and immunity genes rapidly evolved in primates at discrete sites of host-pathogen interactions".Genome Research.19(5): 850–858.doi:10.1101/gr.085647.108.PMC2675973.PMID19299565.

- ^abcGenovese G, Friedman DJ, Ross MD, Lecordier L, Uzureau P, Freedman BI, et al. (August 2010)."Association of trypanolytic ApoL1 variants with kidney disease in African Americans".Science.329(5993): 841–845.Bibcode:2010Sci...329..841G.doi:10.1126/science.1193032.PMC2980843.PMID20647424.

- ^Wasser WG, Tzur S, Wolday D, Adu D, Baumstein D, Rosset S, Skorecki K (2012). "Population genetics of chronic kidney disease: the evolving story of APOL1".Journal of Nephrology.25(5): 603–618.doi:10.5301/jn.5000179.PMID22878977.

- ^Lipkowitz MS, Freedman BI, Langefeld CD, Comeau ME, Bowden DW, Kao WH, et al. (January 2013)."Apolipoprotein L1 gene variants associate with hypertension-attributed nephropathy and the rate of kidney function decline in African Americans".Kidney International.83(1): 114–120.doi:10.1038/ki.2012.263.PMC3484228.PMID22832513.

- ^Duchateau PN, Pullinger CR, Orellana RE, Kunitake ST, Naya-Vigne J, O'Connor PM, et al. (October 1997)."Apolipoprotein L, a new human high density lipoprotein apolipoprotein expressed by the pancreas. Identification, cloning, characterization, and plasma distribution of apolipoprotein L".The Journal of Biological Chemistry.272(41): 25576–25582.doi:10.1074/jbc.272.41.25576.PMID9325276.

- ^Pérez-Morga D, Vanhollebeke B, Paturiaux-Hanocq F, Nolan DP, Lins L, Homblé F, et al. (July 2005). "Apolipoprotein L-I promotes trypanosome lysis by forming pores in lysosomal membranes".Science.309(5733): 469–472.Bibcode:2005Sci...309..469P.doi:10.1126/science.1114566.PMID16020735.S2CID33189804.

- ^Madhavan SM, O'Toole JF, Konieczkowski M, Ganesan S, Bruggeman LA, Sedor JR (November 2011)."APOL1 localization in normal kidney and nondiabetic kidney disease".Journal of the American Society of Nephrology.22(11): 2119–2128.doi:10.1681/ASN.2011010069.PMC3231786.PMID21997392.

- ^Zhaorigetu S, Wan G, Kaini R, Jiang Z, Hu CA (November 2008)."ApoL1, a BH3-only lipid-binding protein, induces autophagic cell death".Autophagy.4(8): 1079–1082.doi:10.4161/auto.7066.PMC2659410.PMID18927493.

- ^Widener J, Nielsen MJ, Shiflett A, Moestrup SK, Hajduk S (September 2007)."Hemoglobin is a co-factor of human trypanosome lytic factor".PLOS Pathogens.3(9): 1250–1261.doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.0030129.PMC1971115.PMID17845074.

- ^abcVanhollebeke B, De Muylder G, Nielsen MJ, Pays A, Tebabi P, Dieu M, et al. (May 2008). "A haptoglobin-hemoglobin receptor conveys innate immunity to Trypanosoma brucei in humans".Science.320(5876): 677–681.Bibcode:2008Sci...320..677V.doi:10.1126/science.1156296.PMID18451305.S2CID206512161.

- ^Vanhollebeke B, Nielsen MJ, Watanabe Y, Truc P, Vanhamme L, Nakajima K, et al. (March 2007)."Distinct roles of haptoglobin-related protein and apolipoprotein L-I in trypanolysis by human serum".Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America.104(10): 4118–4123.Bibcode:2007PNAS..104.4118V.doi:10.1073/pnas.0609902104.PMC1820718.PMID17360487.

- ^Higgins MK, Tkachenko O, Brown A, Reed J, Raper J, Carrington M (January 2013)."Structure of the trypanosome haptoglobin-hemoglobin receptor and implications for nutrient uptake and innate immunity".Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America.110(5): 1905–1910.Bibcode:2013PNAS..110.1905H.doi:10.1073/pnas.1214943110.PMC3562850.PMID23319650.

- ^Green HP, Del Pilar Molina Portela M, St Jean EN, Lugli EB, Raper J (January 2003)."Evidence for a Trypanosoma brucei lipoprotein scavenger receptor".The Journal of Biological Chemistry.278(1): 422–427.doi:10.1074/jbc.M207215200.PMID12401813.