Endometrium

| Endometrium | |

|---|---|

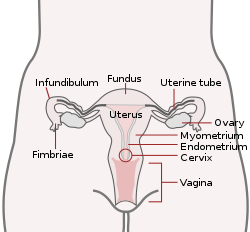

Uterus andfallopian tubes(uterine tubes). (Endometrium labeled at center right.) | |

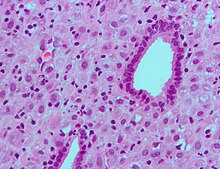

Endometrium in the proliferative phase | |

| Details | |

| Part of | Uterus |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | tunica mucosa uteri |

| MeSH | D004717 |

| TA98 | A09.1.03.027 |

| TA2 | 3521 |

| FMA | 17742 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

Theendometriumis the innerepitheliallayer, along with itsmucous membrane,of themammalianuterus.It has a basal layer and a functional layer: the basal layer containsstem cellswhich regenerate the functional layer.[1]The functional layer thickens and then is shed duringmenstruationin humans and some other mammals, including otherapes,Old World monkeys,some species ofbat,theelephant shrew[2]and theCairo spiny mouse.[3]In most other mammals, the endometrium is reabsorbed in theestrous cycle.Duringpregnancy,the glands andblood vesselsin the endometrium further increase in size and number. Vascular spaces fuse and become interconnected, forming theplacenta,which suppliesoxygenand nutrition to theembryoandfetus.[4][5]The speculated presence of an endometrial microbiota[6] has been argued against.[7][8]

Structure

[edit]

The endometrium consists of a single layer ofcolumnar epitheliumplus thestromaon which it rests. The stroma is a layer ofconnective tissuethat varies in thickness according tohormonalinfluences. In theuterus,simpletubular glandsreach from the endometrial surface through to the base of the stroma, which also carries a rich blood supply provided by thespiral arteries.In women of reproductive age, two layers of endometrium can be distinguished. These two layers occur only in the endometrium lining the cavity of the uterus, and not in the lining of thefallopian tubeswhere a potentially life-threateningectopic pregnancymay occur nearby.[4][5]

- Thefunctional layeris adjacent to the uterine cavity. This layer is built up after the end of menstruation during the first part of the previousmenstrual cycle.Proliferation is induced byestrogen(follicular phase of menstrual cycle), and later changes in this layer are engendered by progesterone from thecorpus luteum(luteal phase). It is adapted to provide an optimum environment for theimplantationand growth of theembryo.This layer is completely shed duringmenstruation.

- Thebasal layer,adjacent to themyometriumand below the functional layer, is not shed at any time during the menstrual cycle. It contains stem cells that regenerate the functional layer,[1]which develops on top of it.

In the absence of progesterone, the arteries supplying blood to the functional layer constrict, so that cells in that layer becomeischaemicand die, leading tomenstruation.

It is possible to identify the phase of the menstrual cycle by reference to either theovarian cycleor theuterine cycleby observing microscopic differences at each phase—for example in the ovarian cycle:

| Phase | Days | Thickness | Epithelium |

|---|---|---|---|

| Menstrual phase | 1–5 | Thin | Absent |

| Follicular phase | 5–14 | Intermediate | Columnar |

| Luteal phase | 15–27 | Thick | Columnar. Also visible arearcuate vessels of uterus |

| Ischemic phase | 27–28 | Columnar. Also visible are arcuate vessels of uterus |

Gene and protein expression

[edit]About 20,000 protein coding genes are expressed in human cells and some 70% of these genes are expressed in the normal endometrium.[9][10]Just over 100 of these genes are more specifically expressed in the endometrium with only a handful genes being highly endometrium specific. The corresponding specific proteins are expressed in the glandular and stromal cells of the endometrial mucosa. The expression of many of these proteins vary depending on the menstrual cycle, for example theprogesterone receptorandthyrotropin-releasing hormoneboth expressed in the proliferative phase, andPAEPexpressed in the secretory phase. Other proteins such as theHOX11protein that is required for female fertility, is expressed in endometrial stroma cells throughout the menstrual cycle. Certain specific proteins such as theestrogen receptorare also expressed in other types of female tissue types, such as thecervix,fallopian tubes,ovariesandbreast.[11]

Microbiome speculation

[edit]The uterus and endometrium was for a long time thought to be sterile. Thecervical plugof mucosa was seen to prevent the entry of anymicroorganismsascending from the vagina. In the 1980s this view was challenged when it was shown that uterine infections could arise from weaknesses in the barrier of the cervical plug. Organisms from the vaginal microbiota could enter the uterus duringuterine contractionsin the menstrual cycle. Further studies sought to identify microbiota specific to the uterus which would be of help in identifying cases of unsuccessfulIVFand miscarriages. Their findings were seen to be unreliable due to the possibility of cross-contamination in the sampling procedures used. The well-documented presence ofLactobacillusspecies, for example, was easily explained by an increase in the vaginal population being able to seep into the cervical mucous.[7]Another study highlighted the flaws of the earlier studies including cross-contamination. It was also argued that the evidence from studies using germ-free offspring ofaxenicanimals (germ-free) clearly showed the sterility of the uterus. The authors concluded that in light of these findings there was no existence of amicrobiome.[8]

The normal dominance of Lactobacilli in the vagina is seen as a marker for vaginal health. However, in the uterus this much lower population is seen as invasive in a closed environment that is highly regulated by female sex hormones, and that could have unwanted consequences. In studies ofendometriosisLactobacillusis not the dominant type and there are higher levels ofStreptococcusandStaphylococcusspecies. Half of the cases ofbacterial vaginitisshowed a polymicrobialbiofilmattached to the endometrium.[7]

Function

[edit]The endometrium is the innermost lining layer of theuterus,and functions to prevent adhesions between the opposed walls of themyometrium,thereby maintaining the patency of the uterine cavity.[12]During themenstrual cycleorestrous cycle,the endometrium grows to a thick, blood vessel-rich, glandular tissue layer. This represents an optimal environment for theimplantationof ablastocystupon its arrival in the uterus. The endometrium is central, echogenic (detectable using ultrasound scanners), and has an average thickness of 6.7 mm.

Duringpregnancy,the glands andblood vesselsin the endometrium further increase in size and number. Vascular spaces fuse and become interconnected, forming theplacenta,which suppliesoxygenand nutrition to theembryoandfetus.

Cycle

[edit]The functional layer of the endometrial lining undergoes cyclic regeneration from stem cells in the basal layer.[1]Humans, apes, and some other species display themenstrual cycle,whereas most other mammals are subject to anestrous cycle.[2]In both cases, the endometrium initially proliferates under the influence ofestrogen.However, onceovulationoccurs, the ovary (specifically the corpus luteum) will produce much larger amounts ofprogesterone.This changes the proliferative pattern of the endometrium to a secretory lining. Eventually, the secretory lining provides a hospitable environment for one or more blastocysts.

Upon fertilization, the egg may implant into the uterine wall and provide feedback to the body withhuman chorionic gonadotropin(hCG). hCG provides continued feedback throughout pregnancy by maintaining the corpus luteum, which will continue its role of releasing progesterone and estrogen. In case of implantation, the endometrial lining remains asdecidua.The decidua becomes part of the placenta; it provides support and protection for the gestation.

Without implantation of a fertilized egg, the endometrial lining is either reabsorbed (estrous cycle) or shed (menstrual cycle). In the latter case, the process of shedding involves the breaking down of the lining, the tearing of small connective blood vessels, and the loss of the tissue and blood that had constituted it through thevagina.The entire process occurs over a period of several days. Menstruation may be accompanied by a series of uterine contractions; these help expel the menstrual endometrium.

If there is inadequate stimulation of the lining, due to lack of hormones, the endometrium remains thin and inactive. In humans, this will result inamenorrhea,or the absence of a menstrual period. Aftermenopause,the lining is often described as being atrophic. In contrast, endometrium that is chronically exposed to estrogens, but not to progesterone, may becomehyperplastic.Long-term use oforal contraceptiveswith highly potentprogestinscan also induce endometrialatrophy.[13][14]

In humans, the cycle of building and shedding the endometrial lining lasts an average of 28 days. The endometrium develops at different rates in different mammals. Various factors including the seasons, climate, and stress can affect its development. The endometrium itself produces certainhormonesat different stages of the cycle and this affects other parts of thereproductive system.

Diseases related with endometrium

[edit]

(A) proliferative endometrium (Left: HE × 400) and proliferative endometrial cells (Right: HE × 100)

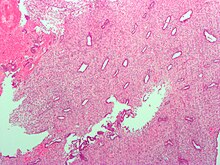

(B) secretory endometrium (Left: HE × 10) and secretory endometrial cells (Right: HE × 10)

(C) atrophic endometrium (Left: HE × 10) and atrophic endometrial cells (Right: HE × 10)

(D) mixed endometrium (Left: HE × 10) and mixed endometrial cells (Right: HE × 10)

(E): endometrial atypical hyperplasia (Left: HE × 10) and endometrial atypical cells (Right: HE × 200)

(F) endometrial carcinoma (Left: HE × 400) and endometrial cancer cells (Right: HE × 400).

Chorionic tissuecan result in marked endometrial changes, known as anArias-Stella reaction,that have an appearance similar tocancer.[15]Historically, this change was diagnosed asendometrial cancerand it is important only in so far as it should not be misdiagnosed as cancer.

- Adenomyosisis the growth of the endometrium into the muscle layer of the uterus (themyometrium).

- Endometriosisis the growth of tissue similar to the endometrium, outside the uterus.[16]

- Endometrial hyperplasia

- Endometrial canceris the most commoncancerof the human female genital tract.

- Asherman's syndrome,also known as intrauterineadhesions,occurs when the basal layer of the endometrium is damaged by instrumentation (e.g.,D&C) or infection (e.g., endometrialtuberculosis) resulting in endometrial sclerosis and adhesion formation partially or completely obliterating the uterine cavity.

Thin endometrium may be defined as an endometrial thickness of less than 8 mm. It usually occurs aftermenopause.Treatments that can improve endometrial thickness includeVitamin E,L-arginineandsildenafil citrate.[17]

Gene expression profilingusingcDNA microarraycan be used for the diagnosis of endometrial disorders.[18] TheEuropean Menopause and Andropause Society(EMAS) released Guidelines with detailed information to assess the endometrium. [19]

Embryo transfer

[edit]

An endometrial thickness (EMT) of less than 7 mm decreases the pregnancy rate inin vitro fertilizationby anodds ratioof approximately 0.4 compared to an EMT of over 7 mm. However, such low thickness rarely occurs, and any routine use of this parameter is regarded as not justified. The optimal endometrial thickness is 10mm. Nevertheless, in human a perfect synchrony it is not necessary, if the emdometrium is not ready to receive the embryo a ectopic pregnancy may occur. This consist of the implantation of the blast outside the uterus, which can be extremely dangerous.[20]

Observation of the endometrium bytransvaginal ultrasonographyis used when administeringfertility medication,such as inin vitro fertilization.At the time ofembryo transfer,it is favorable to have an endometrium of a thickness of between 7 and 14mmwith atriple-lineconfiguration,[21]which means that the endometrium contains ahyperechoic(usually displayed as light) line in the middle surrounded by two morehypoechoic(darker) lines. Atriple-lineendometrium reflects the separation of the basal layer and the functional layer, and is also observed in the periovulatory period secondary to risingestradiollevels, and disappears after ovulation.[22]

Endometrial thickness is also associated with live births in IVF. The live birth rate in a normal endometrium is halved when the thickness is <5mm.[23]

Endometrial protection

[edit]Estrogens stimulate endometrialproliferationandcarcinogenesis.[24][25][26]Conversely, progestogens inhibit endometrial proliferation and carcinogenesis caused by estrogens and stimulatedifferentiationof the endometrium intodecidua,which is termedendometrial transformationor decidualization.[24][25][26]This is mediated by the progestogenic and functionalantiestrogeniceffects of progestogens in this tissue.[25]These effects of progestogens and their protection againstendometrial hyperplasiaandendometrial cancercaused by estrogens is referred to asendometrial protection.[24][25][26]

Additional images

[edit]-

Endometrioid adenocarcinoma from biopsy. H&E stain.

-

Micrograph of decidualized endometrium due to exogenousprogesterone.H&E stain.

-

Micrograph of decidualized endometrium due to exogenous progesterone. H&E stain.

-

Micrograph showing endometrial stromal condensation, a finding seen inmenses.

See also

[edit]- CYTL1,also known as cytokine-like like protein 1.

- Endometrial ablation

- List of distinct cell types in the adult human body

References

[edit]- ^abcGargett, C.E.; Schwab, K.E.; Zillwood, R.M.; Nguyen, H.P.; Wu, D. (June 2009)."Isolation and culture of epithelial progenitors and mesenchymal stem cells from human endometrium".Biology of Reproduction.80(6): 1136–1145.doi:10.1095/biolreprod.108.075226.PMC2849811.PMID19228591.

- ^abEmera, D; Romero, R; Wagner, G (January 2012)."The evolution of menstruation: a new model for genetic assimilation: explaining molecular origins of maternal responses to fetal invasiveness".BioEssays.34(1): 26–35.doi:10.1002/bies.201100099.PMC3528014.PMID22057551.

- ^Bellofiore, N.; Ellery, S.; Mamrot, J.; Walker, D.; Temple-Smith, P.; Dickinson, H. (2016-06-03)."First evidence of a menstruating rodent: the spiny mouse (Acomys cahirinus)".bioRxiv.216(1): 40.e1–40.e11.doi:10.1101/056895.PMID27503621.S2CID196624853.

- ^abBlue Histology - Female Reproductive SystemArchived2007-02-21 at theWayback Machine.School of Anatomy and Human Biology — The University of Western Australia Accessed 20061228 20:35

- ^abGuyton AC, Hall JE, eds. (2006). "Chapter 81 Female Physiology Before Pregnancy and Female Hormones".Textbook of Medical Physiology(11th ed.). Elsevier Saunders. pp. 1018ff.ISBN9780721602400.

- ^Franasiak, Jason M.; Scott, Richard T. (2015)."Reproductive tract microbiome in assisted reproductive technologies".Fertility and Sterility.104(6): 1364–1371.doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2015.10.012.ISSN0015-0282.PMID26597628.

- ^abcBaker, JM; Chase, DM; Herbst-Kralovetz, MM (2018)."Uterine Microbiota: Residents, Tourists, or Invaders?".Frontiers in Immunology.9:208.doi:10.3389/fimmu.2018.00208.PMC5840171.PMID29552006.

- ^abPerez-Muñoz, ME; Arrieta, MC; Ramer-Tait, AE; Walter, J (28 April 2017)."A critical assessment of the" sterile womb "and" in utero colonization "hypotheses: implications for research on the pioneer infant microbiome".Microbiome.5(1): 48.doi:10.1186/s40168-017-0268-4.PMC5410102.PMID28454555.

- ^"The human proteome in endometrium - The Human Protein Atlas".www.proteinatlas.org.Retrieved2017-09-25.

- ^Uhlén, Mathias; Fagerberg, Linn; Hallström, Björn M.; Lindskog, Cecilia; Oksvold, Per; Mardinoglu, Adil; Sivertsson, Åsa; Kampf, Caroline; Sjöstedt, Evelina (2015-01-23). "Tissue-based map of the human proteome".Science.347(6220): 1260419.doi:10.1126/science.1260419.ISSN0036-8075.PMID25613900.S2CID802377.

- ^Zieba, Agata; Sjöstedt, Evelina; Olovsson, Matts; Fagerberg, Linn; Hallström, Björn M.; Oskarsson, Linda; Edlund, Karolina; Tolf, Anna; Uhlen, Mathias (2015-10-21). "The Human Endometrium-Specific Proteome Defined by Transcriptomics and Antibody-Based Profiling".OMICS: A Journal of Integrative Biology.19(11): 659–668.doi:10.1089/omi.2015.0115.PMID26488136.

- ^"Dictionary - Normal: Endometrium - The Human Protein Atlas".www.proteinatlas.org.Retrieved28 December2022.

- ^Deligdisch, L. (1993). "Effects of hormone therapy on the endometrium".Modern Pathology.6(1): 94–106.PMID8426860.

- ^William's Gynecology, McGraw 2008, Chapter 8, Abnormal Uterine Bleeding

- ^Arias-Stella, J. (Jan 2002). "The Arias-Stella reaction: facts and fancies four decades after".Adv Anat Pathol.9(1): 12–23.doi:10.1097/00125480-200201000-00003.PMID11756756.S2CID26249687.

- ^Laganà, AS; Garzon, S; Götte, M (10 Nov 2019)."The Pathogenesis of Endometriosis: Molecular and Cell Biology Insights".International Journal of Molecular Sciences.20(22): 5615.doi:10.3390/ijms20225615.PMC6888544.PMID31717614.

- ^Takasaki A, Tamura H, Miwa I, Taketani T, Shimamura K, Sugino N (April 2010)."Endometrial growth and uterine blood flow: a pilot study for improving endometrial thickness in the patients with a thin endometrium".Fertil. Steril.93(6): 1851–8.doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.12.062.PMID19200982.

- ^Tseng, L.; Chen, I.; Chen, M.; Yan, H.; Wang, C.; Lee, C. (2010)."Genome-based expression profiling as a single standardized microarray platform for the diagnosis of endometrial disorder: an array of 126-gene model".Fertility and Sterility.94(1): 114–119.doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.01.130.PMID19328470.

- ^Dreisler E, Poulsen LG, Antonsen SL, Ceausu I, Depypere H, Erel CT, Lambrinoudaki I, Pérez-López FR, Simoncini T, Tremollieres F, Rees M, Ulrich LG (2013). "EMAS clinical guide: Assessment of the endometrium in peri and postmenopausal women".Maturita.75(2): 181–90.doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2013.03.011.PMID23619009.

- ^Kasius, A.; Smit, J. G.; Torrance, H. L.; Eijkemans, M. J. C.; Mol, B. W.; Opmeer, B. C.; Broekmans, F. J. M. (2014)."Endometrial thickness and pregnancy rates after IVF: a systematic review and meta-analysis".Human Reproduction Update.20(4): 530–541.doi:10.1093/humupd/dmu011.ISSN1355-4786.PMID24664156.

- ^Zhao, Jing; Zhang, Qiong; Li, Yanping (2012)."The effect of endometrial thickness and pattern measured by ultrasonography on pregnancy outcomes during IVF-ET cycles".Reproductive Biology and Endocrinology.10(1): 100.doi:10.1186/1477-7827-10-100.ISSN1477-7827.PMC3551825.PMID23190428.

- ^Baerwald, A. R.; Pierson, R. A. (2004)."Endometrial development in association with ovarian follicular waves during the menstrual cycle".Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynecology.24(4): 453–460.doi:10.1002/uog.1123.ISSN0960-7692.PMC2891966.PMID15343603.

- ^1. Gallos, I. D. et al. Optimal endometrial thickness to maximize live births and minimize pregnancy losses: Analysis of 25,767 fresh embryo transfers. Reprod. Biomed. Online 37, 542–548 (2018).

- ^abcMueck AO, Seeger H, Rabe T (December 2010)."Hormonal contraception and risk of endometrial cancer: a systematic review".Endocr Relat Cancer.17(4): R263–71.doi:10.1677/ERC-10-0076.PMID20870686.

- ^abcdKuhl H (August 2005). "Pharmacology of estrogens and progestogens: influence of different routes of administration".Climacteric.8(Suppl 1): 3–63.doi:10.1080/13697130500148875.PMID16112947.S2CID24616324.

- ^abcHamoda H (March 2022). "British Menopause Society tools for clinicians: Progestogens and endometrial protection".Post Reprod Health.28(1): 40–46.doi:10.1177/20533691211058030.PMID34841960.S2CID244749616.

External links

[edit]- Anatomy figure: 43:05-15at Human Anatomy Online, SUNY Downstate Medical Center - "The uterus, uterine tubes and ovary with associated structures."

- Histology image: 18902loa– Histology Learning System at Boston University - "Female Reproductive System uterus, endometrium"

- Swiss embryology(fromUL,UB,andUF)gnidation/role02

- Histology image: 20_01at the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center

- Histology at utah.edu. Slide is proliferative phase - click forward to see secretory phase