Vocative case

This articleneeds additional citations forverification.(July 2012) |

Ingrammar,thevocativecase(abbreviatedVOC) is agrammatical casewhich is used for anounthat identifies a person (animal, object, etc.) being addressed or occasionally for the noun modifiers (determiners,adjectives,participles,andnumerals) of that noun. Avocative expressionis an expression of direct address by which the identity of the party spoken to is set forth expressly within a sentence. For example, in the sentence "I don't know, John,"Johnis a vocative expression that indicates the party being addressed, as opposed to the sentence "I don't know John", in which "John" is thedirect objectof the verb "know".

Historically, the vocative case was an element of the Indo-European case system and existed inLatin,Sanskrit,andAncient Greek.Many modern Indo-European languages (English, Spanish, etc.) have lost the vocative case, but others retain it, including theBaltic languages,someCeltic languagesand mostSlavic languages.Some linguists, such asAlbert Thumb,argue that the vocative form is not a case but a special form of nouns not belonging to any case, as vocative expressions are not related syntactically to other words in sentences.[1]Pronounsusually lack vocative forms.

Indo-European languages

[edit]Comparison

[edit]Distinct vocative forms are assumed to have existed in all earlyIndo-European languagesand survive in some. Here is, for example, the Indo-European word for "wolf" in various languages:

| Language | Nominative | Vocative |

|---|---|---|

| Proto-Indo-European | *wl̩kʷ-o-s | *wl̩kʷ-e |

| Sanskrit | वृकः(vṛ́k-a-ḥ) | वृक(vṛ́k-a) |

| Classical Greek | λύκ-ο-ς(lúk-o-s) | λύκ-ε(lúk-e) |

| Latin | lup-u-s | lup-e |

| Lithuanian | vilk-a-s | vilk-e |

| Old Church Slavonic | вльк-ъ(vlĭk-ŭ) | вльч-е(vlĭč-e) |

The elements separated with hyphens denote the stem, the so-called thematic vowel of the case and the actual suffix. In Latin, for example, the nominative case islupusand the vocative case islupe,but the accusative case islupum.The asterisks before the Proto-Indo-European words means that they are theoretical reconstructions and are not attested in a written source. The symbol ◌̩ (vertical line below) indicates a consonant serving as a vowel (it should appear directly below the "l" or "r" in these examples but may appear after them on some systems from issues of font display). All final consonants were lost in Proto-Slavic, so both the nominative and vocative Old Church Slavonic forms do not have true endings, only reflexes of the old thematic vowels.

The vocative ending changes the stem consonant in Old Church Slavonic because of the so-called First Palatalization. Most modern Slavic languages that retain the vocative case have altered the ending to avoid the change: Bulgarianвълкоoccurs far more frequently thanвълче.

Baltic languages

[edit]Lithuanian

[edit]The vocative is distinct in singular and identical to the nominative in the plural, for all inflected nouns. Nouns with a nominative singular ending in-ahave a vocative singular usually identically written but distinct in accentuation.

In Lithuanian, the form that a given noun takes depends on its declension class and, sometimes, on its gender. There have been several changes in history, the last being the-aiending formed between the 18th and 19th centuries. The older forms are listed under "other forms".

| Masculine nouns | Nominative | Vocative | Translation | Feminine nouns | Nominative | Vocative | Translation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Current standard | Other forms | Current standard | Other forms | ||||||

| o-stems | vilkas | vilke! | wolf | a-stems | tautà[sg.] | taũta! | people | ||

| jo-stems | vėjas | vėjau! | Old. Lith.vėje! | wind | e-stems | katė | kate! | cat | |

| ijo-stems | gaidys | gaidy! | rooster | i-stems | avis | avie! | sheep | ||

| a-stems | viršilà | viršìla! | sergeant-major | r-stems | duktė | dukterie! | dukter! | daughter | |

| e-stems | dėdė | dėde! | uncle | irregular | marti | marti/marčia! | daughter-in-law | ||

| i-stems | vagis | vagie! | thief | proper names | Dalià | Dãlia! | |||

| u-stems | sūnus | sūnau! | son | diminutives | sesutė | sesut(e)! | little sister | ||

| n-stems | vanduo | vandenie! | vanden! | water | |||||

| proper names | Jonas | Jonai! | Old Lith.Jone! | John | |||||

| diminutives | sūnelis | sūneli! | little son | ||||||

Some nouns of the e- and a- stems declensions (both proper ones and not) are stressed differently: "aikštė":"aikšte! "(square); "tauta ":"tauta! ". In addition, nouns of e-stems have anablautof long vowelėin nominative and short vowele/ɛ/in vocative. In pronunciation,ėisclose-mid vowel[eː],andeis open-mid vowel/ɛ/.

The vocative of diminutive nouns with the suffix-(i)ukasmost frequently has no ending:broliùk"brother!", etc. A less frequent alternative is the ending-ai,which is also slightly dialectal:broliùkai,etc.

Colloquially, some personal names with a masculine-(i)(j)ostem and diminutives with the suffixes-elis, -ėlishave an alternative vocative singular form characterized by a zero ending (i.e. the stem alone acts as the voc. sg.):Adõm"Adam!" in addition toAdõmai,Mýkol"Michael!" in addition toMýkolai,vaikẽl"kid!" in addition tovaikẽli,etc.

Celtic languages

[edit]Goidelic languages

[edit]Irish

[edit]The vocative case inIrishoperates in a similar fashion to Scottish Gaelic. The principal marker is the vocative particlea,which causeslenitionof the initial letter.

In the singular there is no special form, except for first declension nouns. These are masculine nouns that end in a broad (non-palatal) consonant, which is made slender (palatal) to build the singular vocative (as well as the singular genitive and plural nominative). Adjectives are alsolenited.In many cases this means that (in the singular) masculine vocative expressions resemble thegenitiveand feminine vocative expressions resemble thenominative.

The vocative plural is usually the same as the nominative plural except, again, for first declension nouns. In the standard language first declension nouns show the vocative plural by adding-a.In the spoken dialects the vocative plural is often has the same form as the nominative plural (as with the nouns of other declensions) or the dative plural (e.g.A fhearaibh!= Men!)

| Gender | Masculine | Feminine | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sg. | Nominative | an fear mór | an buachaill mór | Seán | an bhean mhór | an deirfiúr mhór | Máire |

| Genitive | an fhir mhóir | an bhuachalla mhóir | Sheáin | na mná móire | na deirféar móire | Mháire | |

| Vocative | a fhir mhóir | a bhuachaill mhóir | a Sheáin | a bhean mhór | a dheirfiúr mhór | a Mháire | |

| Pl. | Nominative | na fir móra | na buachaillí móra | na mná móra | na deirfiúracha móra | ||

| Genitive | na bhfear mór | na mbuachaillí móra | na mban mór | na ndeirfiúracha móra | |||

| Vocative | a fheara móra | a bhuachaillí móra | a mhná móra | a dheirfiúracha móra | |||

| English | the big man | the big boy | John | the big woman | the big sister | Mary | |

Scottish Gaelic

[edit]The vocative case inScottish Gaelicfollows the same basic pattern as Irish. The vocative case causeslenitionof the initial consonant of nouns. Lenition changes the initial sound of the word (or name).

In addition, masculine nouns are slenderized if possible (that is, in writing, an 'i' is inserted before the final consonant) This also changes the pronunciation of the word.

Also, the particleais placed before the noun unless it begins with a vowel (or f followed immediately by a vowel, which becomes silent when lenited). Examples of the use of the vocative personal names (as in Irish):

| Nominative case | Vocative case |

|---|---|

| Caitrìona | a Chaitrìona |

| Dòmhnall | a Dhòmhnaill |

| Màiri | a Mhàiri |

| Seumas | a Sheumais |

| Ùna | Ùna |

| cù | a choin |

| bean | a bhean |

| duine | a dhuine |

The name "Hamish" is just the English spelling ofSheumais(the vocative ofSeumasand pronouncedˈheːmɪʃ), and thus is actually a Gaelic vocative. Likewise, the name "Vairi" is an English spelling ofMhàiri,the vocative forMàiri.

Manx

[edit]The basic pattern is similar to Irish and Scottish. The vocative is confined to personal names, in which it is common. Foreign names (not of Manx origin) are not used in the vocative. The vocative case causeslenitionof the initial consonant of names. It can be used with the particle "y".

| Nominative case | Vocative case |

|---|---|

| Juan | y Yuan |

| Donal | y Ghonal |

| Moirrey | y Voirrey |

| Catreeney | y Chatreeney |

| John | John |

The nameVoirreyis actually the Manx vocative ofMoirrey(Mary).

Brythonic languages

[edit]Welsh

[edit]

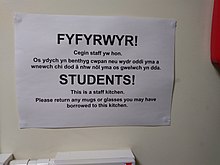

Welshlacks case declension but marks vocative constructions by lenition of the initial consonant of the word, with no obligatory particle. Despite its use being less common, it is still used in formal address: the common phrasefoneddigion a boneddigesaumeans "gentlemen and ladies", with the initial consonant ofboneddigionundergoing a soft mutation; the same is true ofgyfeillion( "[dear] friends" ) in whichcyfeillionhas been lenited. It is often used to draw attention to at public notices orally and written – teachers will say "Blant"(mutation ofplant'children') and signage such as one right show mutation ofmyfyrwyr'students'to draw attention to the importance of the notice.

Germanic languages

[edit]English

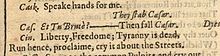

[edit]The vocative is not generally marked in English in regular communication. A vocative expression in English may be marked by theparticle"O" preceding the noun; this is often used in English translations of languages that do have the vocative case. It is often seen in theKing James Versionof theBible:"O ye of little faith" (inMatthew8:26). While it is not strictly archaic, it is sometimes used to "archaeise" speech; it is often seen as very formal, and sees use in rhetoric and poetry, or as a comedic device to subvert modern speech. Another example is the recurrent use of the phrase "O (my) Best Beloved" byRudyard Kiplingin hisJust So Stories.The use ofOmay be considered a form ofcliticand should not be confused with the interjectionoh.[2]However, as theOxford English Dictionarypoints out, "O" and "oh" were originally used interchangeably. With the advent of "oh" as a writteninterjection,however, "O" is the preferred modern spelling in vocative phrases.[citation needed]

Modern English commonly uses the objective case for vocative expressions but sets them off from the rest of the sentences with pauses as interjections, rendered in writing as commas (thevocative comma[3][4]). Two common examples of vocative expressions in English are the phrases "Mr. President" and "Madam Chairwoman".[clarification needed]

Some traditional texts useJesu,the Latin vocative form ofJesus.One of the best-known examples isJesu, Joy of Man's Desiring.

German dialects

[edit]In someGerman dialects,like theRipuariandialect ofCologne,it is common to use the (gender-appropriate) article before a person's name. In the vocative phrase then the article is, as in Venetian and Catalan, omitted. Thus, the determiner precedes nouns in all cases except the vocative. Any noun not preceded by an article or other determiner is in the vocative case. It is most often used to address someone or some group of living beings, usually in conjunction with an imperative construct. It can also be used to address dead matter as if the matter could react or to tell something astonishing or just happening such as "Your nose is dripping."

Colognianexamples:

| Do es der Päul — Päul, kumm ens erövver! | There is Paul. Paul, come over [please]! |

| Och do leeven Kaffepott, do bes jo am dröppe! | O [my] dear coffee pot, you are dripping! |

| „Pääde, jooht loufe! “Un di Pääde jonn loufe. | "Horses, run away!" And the horses are running away. |

Icelandic

[edit]The vocative case generally does not appear inIcelandic,but a few words retain an archaic vocative declension from Latin, such as the wordJesús,which isJesúin the vocative. That comes from Latin, as the Latin for Jesus in the nominative isJesusand its vocative isJesu. That is also the case in traditional English (without the accent) (seeabove):

| Nominative | Jesúselskar þig. | Jesus loves you. |

|---|---|---|

| Vocative | ÓJesú,frelsari okkar. | O Jesus, our saviour. |

The native wordssonur'son'andvinur'friend'also sometimes appear in the shortened formssonandvinin vocative phrases. Additionally, adjectives in vocative phrases are always weakly declined, but elsewhere with proper nouns, they would usually be declined strongly:

| strong adjective, full noun | Kærvinurer gulli betri. | A dear friend is better than gold. |

|---|---|---|

| weak adjective, shortened noun | Kærivin,segðu mér nú sögu. | Dear friend, tell me a story. |

Norwegian

[edit]Nouns inNorwegianare not inflected for the vocative case, but adjectives qualifying those nouns are; adjectivaladjunctsmodifyingvocative nouns are inflected for thedefinite(see:Norwegian language#Adjectives).[5]: 223–224 The definite and plural inflections are in most cases identical, so it is more easily observable with adjectives that inflect for plural and definite differently, e.g.litenbeinglillewhen definite, butsmåwhen plural, an instance ofsuppletion.[5]: 116

| Non-vocative | Vocative | English translation |

|---|---|---|

| kjær venn | kjærevenn | dear friend |

| vis mann | visemann | wise man |

| liten katt | lillekatt | little cat |

In several Norwegian dialects, north of anisoglossrunning fromOslotoBergen,namesinargumentposition are associated withproprial articles,e.g. genderedpronounssuch ashan'he'orhun'she',which either precede or follow the noun in question.[6]This is not the case when in vocative constructions.[7]

Greek

[edit]InAncient Greek,the vocative case is usually identical to the nominative case, with the exception of masculine second-declension nouns (ending in -ος) and third-declension nouns.

Second-declension masculine nouns have a regular vocative ending in -ε. Third-declension nouns with one syllable ending in -ς have a vocative that is identical to the nominative (νύξ,night); otherwise, the stem (with necessary alterations, such as dropping final consonants) serves as the vocative (nom.πόλις,voc.πόλι;nom.σῶμα,gen.σώματος,voc.σῶμα). Irregular vocatives exist as well, such as nom. Σωκράτης, voc. Σώκρατες.

InModern Greek,second-declension masculine nouns still have a vocative ending in -ε. However, the accusative case is often used as a vocative in informal speech for a limited number of nouns, and always used for certain modern Greek person names: "Έλα εδώ, Χρήστο""Come here, Christos "instead of"...Χρήστε".Other nominal declensions use the same form in the vocative as the accusative in formal or informal speech, with the exception of learnedKatharevousaforms that are inherited from Ancient GreekἝλλην(DemoticΈλληνας,"Greek man" ), which have the same nominative and vocative forms instead.[8]

Iranian languages

[edit]Kurdish

[edit]Kurdishhas a vocative case. For instance, in the dialect ofKurmanji,it is created by adding the suffix-oat the end ofmasculinewords and the-êsuffix at the end offeminineones. In theJafi dialectofSoraniit is created by adding the suffix of-iat the end of names.

| Kurmanji | Jafi | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Vocative | Name | Vocative |

| Sedad(m) | Sedo | Bêstûn | Bêsi |

| Wedad(m) | Wedo | Reşîd | Reşo |

| Baran(m) | Baro | Sûret | Sûri |

| Nazdar(f) | Nazê | Fatime | Fati |

| Gulistan(f) | Gulê | Firset | Firsi |

| Berfîn(f) | Berfê | Nesret | Nesi |

Instead of the vocative case, forms of address may be created by using the grammatical particleslê(feminine) andlo(masculine):

| Name | Vocative |

|---|---|

| Nazdar(f) | Lê Nazê! |

| Diyar(m) | Lo Diyar! |

Indo-Aryan languages

[edit]Hindi-Urdu

[edit]InHindi-Urdu(Hindustani), the vocative case has the same form as the nominative case for all singular nouns except for the singular masculine nouns that terminate in the vowelआ/aː/āand for all nouns in their plural forms the vocative case is always distinct from the nominative case.[9]Adjectives inHindi-Urdualso have a vocative case form. In the absence of a noun argument, some adjectives decline like masculine nouns that do not end inआ/aː/ā.[10]The vocative case has many similarities with theoblique casein Hindustani.

| Noun Classes | Singular | Plural | English | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nominative | Vocative | Nominative | Vocative | |||

| Masculine | ending inआā | लड़काlar̥kā | लड़केlar̥ke | लड़कोंlar̥kõ | boy | |

| not ending inआā | इंसानinsān | इंसानोंinsānõ | human | |||

| Feminine | ending inईī | लड़कीlar̥kī | लड़कियाँlar̥kiyā̃ | लड़कियोंlar̥kiyõ | girl | |

| not ending inईī | माताmātā | माताएँmātāẽ | माताओंmātāõ | mother | ||

| चिड़ियाcir̥iyā | चिड़ियाँcir̥iyā̃ | चिड़ियोंcir̥iyõ | bird | |||

| Adjective Classes | Singular | Plural | English | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nominative | Vocative | Nominative | Vocative | ||||

| Declinable | masculine | बुराburā | बुरेbure | bad | |||

| feminine | बुरीburī | ||||||

| Undeclinable (not ending in-āor-īin nominative singular) | masculine | with noun | बेवकूफ़bevakūf | fool | |||

| feminine | |||||||

| masculine | sans noun | बेवकूफ़bevakūf | बेवकूफ़ोंbevakūfõ | ||||

| feminine | |||||||

Sanskrit

[edit]InSanskrit,the vocative (सम्बोधन विभक्तिsambodhana vibhakti) has the same form as the nominative except in the singular. In vowel-stem nouns, if there is a-ḥin the nominative, it is omitted and the stem vowel may be altered:-āand-ĭbecome-e,-ŭbecomes-o,-īand-ūbecome short and-ṛbecomes-ar.Consonant-stem nouns have no ending in the vocative:

| Noun | Singular | Dual | Plural |

|---|---|---|---|

| बाल(bāla,masc., 'boy') | हे बालhe bāla | हे बालौhe bālau | हे बालाःhe bālāḥ |

| लता(latā,fem., 'creeper') | हे लतेhe late | हे लतेhe late | हे लताःhe latāḥ |

| फलम्(phalam,neut., 'fruit') | हे फलम्he phalam | हे फलेhe phale | हे फलानिhe phalāni |

The vocative form is the same as the nominative except in the masculine and feminine singular.

Slavic languages

[edit]Old Church Slavonic

[edit]Old Church Slavonichas a distinct vocative case for many stems of singular masculine and feminine nouns, otherwise it is identical to the nominative. When different from the nominative, the vocative is simply formed from the nominative by appending either-e(rabъ:rabe'slave') or-o(ryba:rybo'fish'), but occasionally-u(krai:kraju'border',synъ:synu'son',vračь:vraču'physician') and'cu'(kostь:kosti'bone',gostь:gosti'guest',dьnь:dьni'day',kamy:kameni'stone') appear. Nouns ending with-ьcьhave a vocative ending of-če(otьcь:otьče'father',kupьcь:kupьče'merchant'), likewise nouns ending with-dzьassume the vocative suffix-že(kъnědzь:kъněže'prince'). This is similar to Greek, Latin, Lithuanian, and Sanskrit, which also employ the-esuffix in vocatives.[11][12]

Bulgarian

[edit]Unlike most otherSlavic languages,Bulgarianhas lost case marking for nouns. However, Bulgarian preserves vocative forms. Traditional male names usually have a vocative ending.

| Nominative | Vocative |

|---|---|

| ПетърPetar | ПетреPetre |

| ТодорTodor | ТодореTodore |

| ИванIvan | ИванеIvane |

More-recent names and foreign names may have a vocative form but it is rarely used (Ричарде,instead of simplyРичардRichard, sounds unusual or humorous to native speakers).

Vocative phrases likeгосподине министре(Mr. Minister) have been almost completely replaced by nominative forms, especially in official writing. Proper nouns usually also have vocative forms, but they are used less frequently. Here are some proper nouns that are frequently used in vocative:

| English word | Nominative | Vocative |

|---|---|---|

| God | БогBog | БожеBozhe |

| Lord | ГосподGospod | ГосподиGospodi |

| Jesus Christ | Исус ХристосIsus Hristos | ИсусеХристеIsuseHriste |

| comrade | другарdrugar | другарюdrugaryu |

| priest | попpop | попеpope |

| frog | жабаzhaba | жабоzhabo |

| fool | глупакglupak | глупакоglupako |

Vocative case forms also normally exist for female given names:

| Nominative | Vocative |

|---|---|

| ЕленаElena | ЕленоEleno |

| ПенаPena | ПеноPeno |

| ЕлицаElitsa | ЕлицеElitse |

| РадкаRadka | РадкеRadke |

Except for forms that end in -е,they are considered rude and are normally avoided. For female kinship terms, the vocative is always used:

| English word | Nominative | Vocative |

|---|---|---|

| Grandmother | БабаBaba | БабоBabo |

| Mom | МайкаMayka МамаMama |

МайкоMayko МамоMamo |

| Aunt | ЛеляLelya | ЛельоLelyo |

| Sister | СестраSestra | СестроSestro |

Czech

[edit]InCzech,the vocative (vokativ,or5. pád–'the fifth case') usually differs from the nominative in masculine and feminine nouns in the singular.

| Nominative case | Vocative case | Gloss |

|---|---|---|

| Feminine | ||

| paní Eva | paní Evo! | 'Ms Eve' |

| knížka | knížko! | 'little book' |

| Marie | Marie! | 'Mary' |

| nová píseň | nová písni! | 'new song' |

| Masculine | ||

| pan profesor | paneprofesore! | 'Mr Professor' |

| Ježíš | Ježíši! | 'Jesus' |

| Marek | Marku! | 'Mark' |

| předseda | předsedo! | 'chairman' |

| pan žalobce | panežalobce! | 'Mr complainant' |

| blbec | blbče! | 'dunce' |

| Jiří | Jiří! | 'George' |

| pan Dobrý | paneDobrý! | 'Mr Good' |

| Neuter | ||

| moje rodné město | moje rodné město! | 'my native city' |

| jitřní moře | jitřní moře! | 'morning sea' |

| otcovo obydlí | otcovo obydlí! | 'father's dwelling' |

In older common Czech (19th century), vocative form was sometimes replaced by nominative form in case of female names (Lojzka, dej pokoj!) and in case of male nouns past a title (pane učitel!,pane továrník!,pane Novák!). This phenomenon was caused mainly by the German influence,[13]and almost disappeared from the modern Czech. It can be felt as rude, discourteous or uncultivated, or as familiar, and is associated also with Slovakian influence (from the Czechoslovak Army) or Russian.[14]In informal speech, it is common (but grammatically incorrect[15]) to use the malesurname(see alsoCzech name) in the nominative to address men:pane Novák!instead ofpane Nováku!(Female surnames areadjectives,and their nominative and vocative have the same form: seeCzech declension.) Using the vocative is strongly recommended in official and written styles.

Polish

[edit]InPolish,the vocative (wołacz) is formed with feminine nouns usually taking-oexcept those that end in-sia,-cia,-nia,and-dzia,which take-u,and those that end in-ść,which take-i.Masculine nouns generally follow the complex pattern of thelocative case,with the exception of a handful of words such asBóg → Boże'God',ojciec → ojcze'father'andchłopiec → chłopcze'boy'.Neuter nouns and all plural nouns have the same form in the nominative and the vocative:

| Nominative case | Vocative case | Gloss |

|---|---|---|

| Feminine | ||

| Pani Ewa | Pani Ewo! | 'Mrs Eve' |

| Ewusia | Ewusiu! | diminutive form ofEwa) |

| ciemność | ciemności! | 'darkness' |

| książka | książko! | 'book' |

| Masculine | ||

| Pan profesor | Panieprofesorze! | 'Mr. Professor' |

| Krzysztof | Krzysztofie! | 'Christopher!' |

| Krzyś | Krzysiu! | 'Chris' |

| wilk | wilku! | 'wolf' |

| człowiek | człowieku! człowiecze!(poetic) |

'human' |

The latter form of the vocative ofczłowiek'human'is now considered poetical.

Thenominativeis increasingly used instead of the vocative to address people with their proper names. In other contexts the vocative remains prevalent. It is used:

- To address an individual with the function, title, other attribute, family role

- Panie doktorze(Doctor!),Panie prezesie!(Chairman!)

- Przybywasz za późno, pływaku(You arrive too late, swimmer)

- synu(son),mamo(mum),tato(dad)

- Afteradjectives,demonstrativepronouns andpossessive pronouns

- Nie rozumiesz mnie, moja droga Basiu!(You don't understand me, my dear Basia!)

- To address an individual in an offensive or condescending manner:

- Zamknij się, pajacu!( "Shut up, you buffoon!" )

- Co się gapisz, idioto?( "What are you staring at, idiot?" )

- Nie znasz się, baranie,to nie pisz!( "Stop writing, idiot, you don't know what you're doing!" )

- Spadaj, wieśniaku!( "Get lost, hillbilly!" )

- After "Ty" (second person singular pronoun)

- Ty kłamczuchu!(You liar!)

- Set expressions:

- (O) Matko!, (O) Boże!, chłopie

The vocative is also often employed in affectionate and endearing contexts such asKocham Cię, Krzysiu!( "I love you, Chris!" ) orTęsknię za Tobą, moja Żono( "I miss you, my wife." ). In addition, the vocative form sometimes takes the place of the nominative in informal conversations:Józiu przyszedłinstead ofJózio przyszedł( "Joey's arrived" ). When referring to someone by their first name, the nominative commonly takes the place of the vocative as well:Ania, chodź tu!instead ofAniu, chodź tu!( "Anne, come here!" ).

Russian

[edit]Historic vocative

[edit]The historic Slavic vocative has been lost inRussianand is now used only in archaic expressions. Several of them, mostly of Old Church Slavonic origin, are common in colloquial Russian: "Боже!"(Bože,vocative of "Бог"Bog,"God" ) and "Боже мой!"(Bože moj,"My God!" ), and "Господи!"(Gospodi,vocative of "Господь"Gospodj,"Lord" ), which can also be expressed as "Господи Иисусе!"(Gospodi Iisuse!,Iisusevocative of "Иисус"Iisus,"Jesus" ). The vocative is also used in prayers: "Отче наш!"(Otče naš,"Our Father!" ). Such expressions are used to express strong emotions (much like English "O my God!" ), and are often combined ( "Господи, Боже мой"). More examples of the historic vocative can be found in other Biblical quotes that are sometimes used as proverbs:"Врачу, исцелися сам"(Vraču, iscelisia sam,"Physician, heal thyself", nom. "врач",vrač). Vocative forms are also used in modernChurch Slavonic.The patriarch and bishops of theRussian Orthodox Churchare addressed as "владыко"(vladyko,hegemon, nom. "владыка",vladyka). In the latter case, the vocative is often also incorrectly used for the nominative to refer to bishops and patriarchs.

New vocative

[edit]In modern colloquial Russian,given namesand a small family of terms often take a special "shortened" form that some linguists consider to be a re-emerging vocative case.[16]It is used only for given names and nouns that end in-aand-я,which are sometimes dropped in the vocative form: "Лен, где ты?"(" Lena, where are you? "). It is basically equivalent to"Лена, где ты?"but suggests a positive personal and emotional bond between the speaker and the person being addressed. Names that end in-яthen acquire asoft sign:"Оль!"="Оля!"(" Olga! "). In addition to given names, the form is often used with words like"мама"(mom) and"папа"(dad), which would be respectively shortened to"мам"and"пап".The plural form is used with words such as"ребят","девчат"(nom:"ребята","девчата"guys, gals).[17]

Such usage differs from the historic vocative, which would be "Лено"and is not related.

Serbo-Croatian

[edit]Distinct vocatives exist only for singular masculine and feminine nouns. Nouns of the neuter gender and all nouns in plural have a vocative equal to the nominative. All vocative suffixes known from Old Church Slavonic also exist in Serbo-Croatian.[18]

The vocative in Serbo-Croatian is formed according to one of three types of declension, which are classes of nouns having equal declension suffixes.[19]

First declension

[edit]The first declension comprises masculine nouns that end with a consonant. These have a vocative suffix of either-e(doktor:doktore'doctor') or-u(gospodar:gospodaru'master').

Nouns terminating in-orhave the-evocative suffix: (doktor: doktore'doctor',major: majore'major',majstor: majstore'artisan') also nouns possessing an unsteadya(vetar: vetre'wind',svekar: svekre'father-in-law') and the nouncar: care'emperor'.All other nouns in this class form the vocative with-u:gospodar: gospodaru'master',pastir: pastiru'shepherd',inženjer: inženjeru'engineer',pisar: pisaru'scribe',sekretar: sekretaru'secretary'.

In particular, masculine nouns ending with a palatal or prepalatal consonantj, lj, nj, č, dž, ć, đoršform vocatives with the-usuffix:heroj: heroju'hero',prijatelj: prijatelju'friend',konj: konju'horse',vozač: vozaču'driver',mladić: mladiću'youngster',kočijaš: kočijašu'coachman',muž: mužu'husband'.

Nouns ending with thevelars-k, -gand-harepalatalizedto-č, -ž, -šin the vocative:vojnik: vojniče'soldier',drug: druže'comrade',duh: duše'ghost'.A final-cbecomes-čin the vocative:stric: striče'uncle',lovac: lovče'hunter'.Likewise, a final-zbecomes-žin only two cases:knez: kneže'prince'andvitez: viteže'knight'.

The loss of the unsteadyacan trigger a sound change by hardening of consonants, as invrabac: vrapče'sparrow'(not*vrabče),lisac: lišče'male fox'(not*lisče) andženomrzac: ženomršče'misogynist'(not*ženomrzče). There may be a loss of-tbefore-clike inotac: oče'father'(instead of*otče),svetac: sveče'saint'(instead of*svetče). When these phonetic alterations would substantially change the base noun, the vocative remains equal to the nominative, for exampletetak'uncle',mačak'male cat',bratac'cousin'.This also holds true for foreign names ending with-k, -gand-hlikeDžek'Jack',Dag'Doug',King, Hajnrih.

Male names ending with-oand-ehave a vocative equal to the infinitive, for example,Marko, Mihailo, Danilo, Đorđe, Pavle, Radoje.

Second declension

[edit]The second declension affects nouns with the ending-a.These are mainly of feminine but sometimes also of masculine gender. These nouns have a vocative suffix-o:riba: ribo"fish",sluga: slugo"servant",kolega: kolego"colleague",poslovođa: poslovođo"manager".

Exemptions to this rule are male and female names, which have a vocative equal to the nominative, e. g.Vera,Zorka,Olga,Marija,Gordana,Nataša,Nikola,Kosta,Ilijaetc. However, this is different for twosyllabic names with an ascending accent such asNâda,Zôra,Mîca,Nênaand the male namesPêra,Bôža,Pâjaetc., which form vocatives with -o:Nâdo,Zôro,Mîco,Pêro,Bôžo,Pâjoetc.

Denominations of relatives likemama"mom",tata"dad",deda"grandfather",tetka"aunt",ujna"aunt" (mother's brother's wife),strina"aunt" (father's brother's wife),baba"grandmother" have vocatives equal to the nominative. This also holds true for country names ending in-ska,-čka,-ška.

Nouns ending with thediminutivesuffix-icathat consist of three or more syllables have a vocative with-e:učiteljica: učiteljice"female teacher",drugarica: drugarice"girlfriend",tatica: tatice"daddy",mamica: mamice"mommy". This also applies to female namesDanica: Danice,Milica: Milice,Zorica: Zorice,and the male namesPerica: Perice,Tomica: Tomice.Nouns of this class that can be applied to both males and females usually have a vocative ending of-ico(pijanica: pijanico"drunkard",izdajica: izdajico"traitor",kukavica: kukavico"coward" ), but vocatives with-iceare also seen.

The use of vocative endings for names varies among Serbo-Croatian dialects. People in Croatia often use only nominative forms as vocatives, while others are more likely to use grammatical vocatives.[20]

Third declension

[edit]The third declension affects feminine nouns ending with a consonant. The vocative is formed by appending the suffix-ito the nominative (reč: reči"word",noć: noći"night" ).

Slovak

[edit]Until the end of the 1980s, the existence of a distinct vocative case inSlovakwas recognised and taught at schools. Today, the case is no longer considered to exist except for a few archaic examples of the original vocative remaining in religious, literary or ironic contexts:

| Nominative | Vocative | Translation | Nominative | Vocative | Translation | Nominative | Vocative | Translation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bohm. | Bože | God | Ježišm. | Ježišu | Jesus | mamaf. | mamo | mother |

| Kristusm. | Kriste | Christ | priateľm. | priateľu | friend | ženaf. | ženo | woman |

| pánm. | pane | lord | bratm. | bratu,bratku | brother | |||

| otecm. | otče | father | synm. | synu,synku | son | |||

| človekm. | človeče | man, human | ||||||

| chlapm. | chlape | man | ||||||

| chlapecm. | chlapče | boy |

In everyday use, the Czech vocative is sometimes retrofitted to certain words:

| Nominative | Vocative | Translation |

|---|---|---|

| majsterm. | majstre | maestro |

| šéfm. | šéfe | boss |

| švagorm. | švagre | brother-in-law |

Another stamp of vernacular vocative is emerging, presumably under the influence ofHungarianfor certain family members or proper names:

| Nominative | Vocative | Translation |

|---|---|---|

| otecm. | oci | father |

| mamaf. | mami | mother |

| babkaf. | babi | grandmother, old woman |

| Paľom. | Pali | Paul, domestic form |

| Zuzaf. | Zuzi | Susan, domestic form |

Ukrainian

[edit]Ukrainianhas retained the vocative case mostly as it was inProto-Slavic:[21]

| Masculine nouns | Feminine nouns | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nominative | Vocative | Translation | Nominative | Vocative | Translation |

| богboh | божеbože | god | матусяmatusja | матусюmatusju | minnie |

| другdruh | дружеdruže | friend | неняnenja | ненеnene | nanny |

| братbrat | братеbrate | brother | бабцяbabcja | бабцюbabcju | granny |

| чоловікčolovik | чоловічеčoloviče | man | жінкаžinka | жінкоžinko | woman |

| хлопецьchlopec' | хлопчеchlopče | boy | дружинаdružyna | дружиноdružyno | wife |

| святий отецьsvjatyj otec' | святий отчеsvjatyj otče | Holy Father | дівчинаdivčyna | дівчиноdivčyno | girl |

| панpan | панеpane | sir, Mr. | сестраsestra | сестроsestro | sister |

| приятельpryjatel' | приятелюpryjatelju | fellow | людинаljudyna | людиноljudyno | human |

| батькоbat'ko | батькуbat'ku | father | |||

| синsyn | синуsynu | son | |||

There are some exceptions:

| Nominative | Vocative | Translation |

|---|---|---|

| матиmatyf. | мамоmamo | mother |

| божа матірboža matirf. | матір божаmatir boža | God's Mother |

It is used even for loanwords and foreign names:

| Nominative | Vocative | Translation |

|---|---|---|

| ДжонDžonm. | ДжонеDžone | John |

| пан президентpan prezydentm. | пане президентеpane prezydente | Mr. President |

It is obligatory for all native names:

| Masculine | Feminine | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Nominative | Vocative | Nominative | Vocative |

| ВолодимирVolodymyr | ВолодимиреVolodymyre | МирославаMyroslava | МирославоMyroslavo |

| СвятославSvjatoslav | СвятославеSvjatoslave | ГаннаHanna | ГанноHanno |

It is used for patronymics:

| Nominative | Vocative |

|---|---|

| Андрій ВасильовичAndrij Vasylovyčm. | Андрію ВасильовичуAndriju Vasyliovyču |

| Ірина БогданівнаIryna Bohdanivnaf. | Ірино БогданівноIryno Bohdanivno |

Latin

[edit]

InLatin,the form of the vocative case of a noun is often the same as the nominative. Exceptions include singular non-neuter second-declension nouns that end in-usin the nominative case. An example would be the famous line from Shakespeare, "Et tu, Brute?"(commonly translated as" And you, Brutus? "):Bruteis the vocative case andBrutuswould be the nominative.

Nouns that end in-iusend with-īinstead of the expected-ie.Thus,JuliusbecomesJulīandfiliusbecomesfilī.The shortening does not shift the accent so the vocative ofVergiliusisVergilī,with accent on the second syllable even though it is short. Nouns that end in-aiusand-eiushave vocatives that end in-aīor-eīeven though the-i-in the nominative is consonantal.

First-declension and second-declension adjectives also have distinct vocative forms in the masculine singular if the nominative ends in-us,with the ending-e.Adjectives that end in-iushave vocatives in-ieso the vocative ofeximiusiseximie.

Nouns and adjectives that end in-eusdo not follow the rules above.Meusforms the vocative irregularly asmīormeus,while ChristianDeusdoes not have a distinct vocative and retains the formDeus."My God!" in Latin is thusmī Deus!,butJerome'sVulgateconsistently usedDeus meusas a vocative.Classical Latindid not use a vocative ofdeuseither (in reference to pagan gods, the Romans used thesuppletiveformdive).

Romance languages

[edit]West Iberian languages

[edit]Portuguesedrops the article to form the vocative. The vocative is always between commas and, like in many other languages, a particleÓis commonly used:

| Ó Jesus, ajude-nos! | O Jesus, help us! |

| Menino, vem cá! | Boy, come here! |

| Não faças isso, amigo. | Don't do that, [my] friend. |

InExtremaduranandFala,some post-tonical vowels open in vocative forms of nouns, a new development that is unrelated to the Latin vocative case.

Catalan

[edit]Catalandrops the article to form the vocative.

French

[edit]Like English,Frenchsometimes uses (or historically used) a particleÔto mark vocative phrases rather than by change to the form of the noun. A famous example is the title and first line of the Canadian national anthem,O Canada(French title:Ô Canada), a vocative phrase addressingCanada.

Romanian

[edit]The vocative case inRomanianis partly inherited, occasionally causing other morphophonemic changes (see also the article onRomanian nouns):

- singular masculine/neuter:-eas in

- om:omule!(man, human being),

- băiat:băiete!orbăiatule!(boy),

- văr:vere!(cousin),

- Ion:Ioane!(John);

- singular feminine:-oas in

- soră:soro!(sister),

- nebună:nebuno!(mad woman), also in masculine (nebunul)

- deșteaptă:deșteapto!(smart one (f), often used sarcastically),

- Ileana:Ileano!(Helen);

Since there is no-ovocative in Latin, it must have been borrowed from Slavic: compare the corresponding Bulgarian formsсестро(sestro),откачалко(otkachalko),Елено(Eleno).

- plural, all genders:-loras in

- frați:fraților!(brothers),

- boi:boilor!(oxen, used toward people as an invective),

- doamne și domni:doamnelor și domnilor!(ladies and gentlemen).

In formal speech, the vocative often simply copies the nominative/accusative form even when it does have its own form. That is because the vocative is often perceived as very direct and so can seem rude.

Romanesco dialect

[edit]InRomanesco dialectthe vocative case appears as a regulartruncationimmediately after thestress.

Compare (vocative, always truncated)

- France', vie' qua!

- "Francesco/Francesca, come here!"

with (nominative, never truncated)

- Francesco/Francesca viene qua

- "Francesco/Francesca comes here"

Venetian

[edit]Venetianhas lost all case endings, like most other Romance languages. However, with feminine proper names the role of the vocative is played by the absence of the determiner: the personal articleła / l'usually precedes feminine names in other situations, even in predicates. Masculine names and other nouns lack articles and so rely onprosodyto mark forms of address:

| Case | Fem. proper name | Masc. proper name and other nouns |

|---|---|---|

| Nom./Acc. | łaMarìa ła vien qua / vardałaMarìa! 'Mary comes here / look at Mary!' |

Marco el vien qua / varda Marco! 'Mark comes here / look at Mark!' |

| Vocative | Marìa vien qua! / varda, Marìa! 'Mary, come here! / look, Mary!' |

Marco vien qua! / varda, Marco! 'Mark, come here! / look, Mark!' |

Predicative constructions:

| Case | Fem. proper name | Masc. proper name and other nouns |

|---|---|---|

| Pred. | so' miłaMarìa 'Iam Mary.' |

so' mi Marco / so' tornà maestra 'Iam Mark. / I am a teacher again.' |

| Vocative | so' mi Marìa! 'It's me, Mary!' |

so' mi, Marco! / so' tornà, maestra! 'It's me, Mark! / I am back, teacher!' |

Arabic

[edit]Properly speaking,Arabichas only three cases:nominative,accusativeandgenitive.However, a meaning similar to that conveyed by the vocative case in other languages is indicated by the use of the particleyā(Arabic:يا) placed before a noun inflected in thenominativecase (oraccusativeif the noun is in construct form). In English translations, it is often translated literally asOinstead of being omitted.[22][23]A longer form used inClassical Arabicisأيّهاayyuhā(masculine),أيّتهاayyatuhā(feminine), sometimes combined withyā.The particleyāwas also used in the oldCastilian languagebecause of Arabic influence viaMozarabicimmigrations.[24]

Mandarin

[edit]Mandarin uses no special inflected forms for address. However, special forms andmorphemes(that are not inflections) exist for addressing.

Mandarin has several particles that can be attached to the word of address to mark certain special vocative forces, where appropriate. A common one isAa,attached to the end of the address word. For example,Nhật kýrìjì"diary" becomesNhật ký arìjì'a.

Certain specialized vocative morphemes also exist, albeit with limited applicabilities. For instance, theBeijing dialectofMandarin Chinese,to express strong feelings (especially negative ones) to someone, a neutral tone suffix-eimay be attached to certain address words. It is most commonly applied to the wordTôn tử(sūnzi,"grandson" ), to formsūnzei,meaning approximately "Hey you nasty one!". Another example isTiểu tử(xiǎozi,lit. "kid; young one" ), resulting inxiǎozei"Hey kiddo!".

Japanese

[edit]The vocative case is present inJapaneseas the particleよ.[25]This usage is often literary or poetic. For example:

| VũよTuyết に変わってくれ! Ameyoyuki ni kawatte kure! |

O Rain! Please change to snow! |

| Vạn quốc の労 động giảよ,Đoàn kết せよ! Bankoku no rōdō-shayo,danketsu seyo! |

Workers of the world, unite! |

In conversational Japanese, this same particle is often used at the end of a sentence to indicate assertiveness, certainty or emphasis.

Georgian

[edit]InGeorgian,the vocative case is used to address the second-person singular and plural. For word roots that end with a consonant, the vocative case suffix is -o,and for the words that end with a vowel, it is -vlike inOld Georgian,but for some words, it is considered archaic. For example,kats-is the root for the word "man". If one addresses someone with the word, it becomeskatso.

Adjectives are also declined in the vocative case. Just like nouns, consonant final stem adjectives take the suffix -oin the vocative case, and the vowel final stems are not changed:

- lamazi kali"beautiful woman" (nominative case)

- lamazokalo!"beautiful woman!" (vocative case)

In the second phrase, both the adjective and the noun are declined. The personal pronouns are also used in the vocative case.Shen"you" (singular) andtkven"you" (plural) in the vocative case becomeshe!andtkve,without the -n.Therefore, one could, for instance, say, with the declension of all of the elements:

She lamazo kalo!"you beautiful woman!"

Korean

[edit]The vocative case inKoreanis commonly used with first names in casual situations by using the vocativecase marker(호격 조사) 아(a) if the name ends in a consonant and야(ya) if the name ends with a vowel:[26]

미진이

Mijini

집에

jibe

가?

ga?

Is Mijin going home?

미진아,

Mijina,

집에

jibe

가?

ga?

Mijin, are you going home?

동배

Dongbae

뭐

mwo

해?

hae?

What is Dongbae doing?

동배야,

Dongbaeya,

뭐

mwo

해?

hae?

Dongbae, what are you doing?

In formal Korean, the marker여(yeo) or이여(iyeo) is used, the latter if the root ends with a consonant. Thus, a quotation ofWilliam S. Clarkwould be translated as follows:

소년이여,

sonyeoniyeo,

야망을

yamangeul

가져라.

gajyeora.

Boys, be ambitious.

Thehonorificinfix시(si) is inserted in between the이(i) and여(yeo).

신이시여,

sinisiyeo,

부디

budi

저들을

jeodeureul

용서하소서.

yongseohasoseo.

Oh god, please forgive them.

InMiddle Korean,there were three honorific classes of the vocative case:[27]

| Form | 하 | 아/야 | 여/이여 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Honorific | High | Plain | Low with added nuance of exclamation |

Hungarian

[edit]Hungarian has a number of vocative-like constructions, even though it lacks an explicit vocativeinflection.

Noun phrases in a vocative context always take the zero article.[28]While noun phrases can takezero articlesfor other reasons, the lack of an article otherwise expected marks a vocative construction. This is especially prominent in dialects of Hungarian where personal proper names and other personal animate nouns tend to take the appropriate definite article, similarly to certain dialects ofGermandetailed above. For example:

| Nominative | Vocative |

|---|---|

| (Az)Olivér még beszélget. Oliver is still chatting. |

Olivér, gyere ide! Oliver, come over here. |

| Kiönthette voln’ahonfi megtelt szívét. Might have pour'd the full tide of a patriot's heart. |

Honfi, mit ér epedő kebel e romok ormán? Patriot, why do you yearn on these ruins?[29] |

| Aszerelem csodaszép. Love is wonderful. |

Látod, szerelem, mit tettél! O Love, look what you have done! |

| (Az)Isten szerelmére! For the love of God! |

Isten, áldd meg a magyart! God, bless the Hungarians! |

With certain words such asbarát( "friend" ),hölgy( "lady" ),úr( "gentleman, lord" ), vocation is, in addition to the zero article, always[30]marked by the first person possessive:[31]

| Nominative | Vocative |

|---|---|

| A nemesek báljára megérkeztekahölgyek ésazurak. The ladies and the gentlemen have arrived to the nobility's ball. |

Hölgyeimés uraim,kezdődjék a tánc! Ladies and gentlemen, let the dancing begin! |

| HaazÚr nem építi a házat, hiába fáradoznak az építők. Unless the Lord builds the house, its builders labor in vain. |

Magasztallak Uram,felemeltél engem! I will exalt you, O Lord, for you lifted me out of the depth! |

| Abarát mindig segít. A friend always helps out. Abarátomfiatal. My friend is young. |

Tudnál segíteni, barátom? Could you help out, (my) friend? |

Words liketestvér( "sibling, brother" ) and other words of relation do not require the first person possessive, but it is readily used in common speech, especially in familiar contexts:

| Nominative | Vocative |

|---|---|

| Atestvérek elsétáltak a boltba. The siblings walked to the shop. |

Kedves testvéreim!/Kedves testvérek! (My) dear brothers (and sisters)! |

| (Az)apához megyek. I'm going to dad. |

Apám,hogy vagy?/Apa, hogy vagy? Dad, how are you? |

The second-person pronoun[30]can be used to emphasize a vocation when appropriate:Hát miért nem adtad oda neki,tebolond?( "Why did you not give it to him, you fool?" ),TeKarcsi, nem láttad a szemüvegem?( "Charlie, have you seen my glasses?" ),Lógtok ezért még,tigazemberek.( "You shall yet hang for this, crooks!" ), etc.

References

[edit]- ^Реформатский А. А.Введение в языковедение / Под ред. В. А. Виноградова. — М.: Аспект Пресс. 1998. С. 488.ISBN5-7567-0202-4(in Russian)

- ^The Chicago Manual of Style,15th ed. (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2003),ISBN0-226-10403-6,s. 5.197.

- ^"What is the Vocative Comma? Definition, Examples in the Vocative Case".Writing Explained.Retrieved2022-07-13.

- ^"Hello, vocative comma".Macmillan Dictionary Blog.2020-01-06.Retrieved2022-07-13.

- ^abHalmøy, Madeleine (2016).The Norwegian Nominal System: a Neo-Saussurean Perspective.Walter de Gruyter GmbH.doi:10.1515/9783110363425.ISBN978-3-11-033963-5.

- ^Johannesen, Janne Bondi; Garbacz, Piotr (2014)."Proprial articles"(PDF).Nordic Atlas of Language Structures.1.University of Oslo: 10–17.doi:10.5617/nals.5362.Archived(PDF)from the original on 2020-11-29.

- ^Håberg, Live (2010)."Den preproprielle artikkelen i norsk: ei undersøking av namneartiklar i Kvæfjord, Gausdal og Voss"[The preproprial article in Norwegian: a study of nominal articles in Kværfjord, Gausdal and Voss](PDF)(in Norwegian).University of Oslo.pp. 26–28.hdl:10852/26729.Archived(PDF)from the original on 2020-11-29.

Ved personnamn i vokativ [...] vil den preproprielle artikkelen ikkje bli brukt.

- ^Holton, David, Irene Philippaki-Warburton, and Peter A. Mackridge,Greek: A Comprehensive Grammar of the Modern Language(Routledge, London and New York:1997), pp. 49–50ISBN0415100011

- ^Shapiro, Michael C. (1989).A Primer of Modern Standard Hindi.New Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. p. 263.ISBN81-208-0475-9.

- ^Kachru, Yamuna (2006).Hindi.Philadelphia, PA: John Benjamins Publishing Company. p. 65.ISBN90-272-3812-X.

- ^Miklosich, Franz(1876).Vergleichende Grammatik der slavischen Sprachen.Vol. 3. Wien: W. Braumüller. p. 3.

- ^Vondrak, Vaclav(1912).Altkirchenslavische Grammatik(2nd ed.). p. 397.

- ^Mathesius, Vilém (1923)."Nominativ místo vokativu v hovorové češtině".Naše řeč(in Czech).7(5): 138–140.

- ^Filinová, Tereza (9 September 2007)."Pátý pád: jde to z kopce?".Radio Prague International.

- ^Bodollová, Květa; Prošek, Martin (31 May 2011)."Oslovování v češtině".Český Rozhlas.

- ^Parrott, Lilli (2010)."Vocatives and Other Direct Address Forms: A Contrastive Study".Oslo Studies in Language.2(1).doi:10.5617/osla.68.

- ^Andersen, Henning (2012). "The New Russian Vocative: Synchrony, Diachrony, Typology".Scando-Slavica.58(1): 122–167.doi:10.1080/00806765.2012.669918.S2CID119842000.

- ^Barić, Eugenija; Lončarić, Mijo; Malić, Dragica; Pavešić, Slavko; Peti, Mirko; Zečević, Vesna; Znika, Marija (1997).Hrvatska gramatika.Školska knjiga.ISBN953-0-40010-1.

- ^Ivan Klajn(2005),Gramatika srpskog jezika,Beograd: Zavod za udžbenike i nastavna sredstva, pp. 50 ff

- ^Alen Orlić (2011)."Vokativ osobnih imena u hrvatskom jeziku"(in Croatian).University of Osijek.Retrieved17 October2018.

- ^Methodical instructions for learning vocative case in Ukrainian professional speech

- ^Jiyad, Mohammed."A Hundred and One Rules! A Short Reference to Arabic Syntactic, Morphological & Phonological Rules for Novice & Intermediate Levels of Proficiency"(DOC).Welcome to Arabic.Retrieved2007-11-28.

- ^"Lesson 5".Madinah Arabic.Retrieved2007-11-28.

- ^Álvarez Blanco, Aquilino (2019)."EL ÁRABE YA¯ (یا) Y SU USO EN CASTELLANO MEDIEVAL. PROBLEMAS DE INTERPRETACIÓN Y TRADUCCIÓN".Anuario de Estudios Filológicos.XLII:5–22 – via Dehesa. Repositorio Institucional de la Universidad de Extremadura.

- ^Shogakukan.Nhật bổn quốc ngữ đại từ điển tinh tuyển bản[Shogakukan's Japanese Dictionary Concise Edition] (in Japanese). Shogakukan.

- ^선철, 김 (May 2005)."'꽃아'의 발음 ".새국어소식 / 국립국어원.

- ^양영희 (2009-12-01)."중세국어 호격조사의 기능 고찰".사회언어학.17.ISSN1226-4822.

- ^Alberti, Gábor; Balogh, Kata (2004)."Az eltűnt névelő nyomában".A mai magyar nyelv leírásának újabb módszerei.6(6): 9-31.

- ^Makkai, Ádám, ed. (2000).In quest of the 'Miracle stag': the poetry of Hungary / [Vol. 1], An anthology of Hungarian poetry in English translation from the 13th century to the present in commemoration of the 1100th anniversary of the Foundation of Hungary and the 40th anniversary of the Hungarian Uprising of 1956 / with the co-operation of George Buday and Louis I. Szathmáry II and the special assistance of Agnes Arany-Makkai, Earl M. Herrick, and Valerie Becker Makkai(Second rev. ed.). Chicago: Atlantis-Centaur.ISBN963-86024-2-2.

- ^abLáncz, Irén (July–August 1997)."A megszólítás nyelvi eszközei Mikszáth Kálmán műveiben"(PDF).Híd.LXI(7–8): 535-543.Retrieved2 October2022.

- ^Albertné Herbszt, Mária (2007). "Pragmatika". In A. László, Anna (ed.).A magyar nyelv könyve(9 kiad ed.). Budapest: Trezor Kiadó. p. 708.ISBN978-963-8144-19-5.