Liberal democracy

This article'slead sectionmay be too long.(March 2024) |

| Part of thePolitics series |

| Democracy |

|---|

|

|

Liberal democracy,western-style democracy,[1]orsubstantive democracy[2]is aform of governmentthat combines the organization of arepresentative democracywith ideas ofliberalpolitical philosophy.

Common elements within a liberal democracy are:electionsbetween or amongmultiple distinctpolitical parties,aseparation of powersinto differentbranches of government,therule of lawin everyday life as part of anopen society,amarket economywithprivate property,universal suffrage,and the equal protection ofhuman rights,civil rights,civil liberties,andpolitical freedomsfor all citizens. Substantive democracy refers tosubstantive rightsandsubstantive laws,which can includesubstantive equality,[2]theequality of outcomefor subgroups in society.[3][4]

To define the system in practice, liberal democracies often draw upon aconstitution,either codified oruncodified,to delineate the powers of government and enshrine thesocial contract.The purpose of a constitution is often seen as a limit on the authority of the government. A liberal democracy may take various and mixed constitutional forms: it may be aconstitutional monarchyor arepublic.It may have aparliamentary system,presidential system,orsemi-presidential system.Liberal democracies are contrasted withilliberal democraciesanddictatorships.

Liberal democracy traces its origins—and its name—to theAge of Enlightenment.The conventional views supportingmonarchiesandaristocracieswere challenged at first by a relatively small group of Enlightenmentintellectuals,who believed that human affairs should be guided byreasonand principles of liberty and equality. They argued thatall people are created equaland therefore political authority cannot be justified on the basis of noble blood, a supposed privileged connection to God, or any other characteristic that is alleged to make one person superior to others.

They further argued that governments exist to serve the people—not vice versa—and that laws should apply to those who govern as well as to the governed (a concept known asrule of law), formulated in Europe asRechtsstaat.Some of these ideas began to be expressed in England in the 17th century.[5]By the late 18th century, leading philosophers such asJohn Lockehad published works that spread around the European continent and beyond. These ideas and beliefs influenced theAmerican Revolutionand theFrench Revolution.After a period of expansion in the second half of the 20th century, liberal democracy became a prevalent political system in the world.[6]

Liberal democracy emphasizes the separation of powers, anindependent judiciary,and a system of checks and balances between branches of government.Multi-party systemswith at least two persistent,viable political partiesare characteristic of liberal democracies. Governmental authority is legitimately exercised only in accordance with written, publicly disclosedlawsadopted and enforced in accordance with established procedure. Some liberal democracies, especially those with large populations, usefederalism(also known as vertical separation of powers) in order to prevent abuse and increase public input by dividing governing powers between municipal, provincial and national governments. The characteristics of liberal democracies are correlated with increased political stability,[7]lowercorruption,[8]better management of resources,[9]and better health indicators such aslife expectancyandinfant mortality.[10]

Origins

[edit]

Liberal democracy traces its origins—and its name—to 18th-century Europe, during theAge of Enlightenment.At the time, the vast majority of European states weremonarchies,with political power held either by themonarchor thearistocracy.The possibility of democracy had not been a seriously considered political theory sinceclassical antiquityand the widely held belief was that democracies would be inherently unstable and chaotic in their policies due to the changing whims of the people. It was further believed that democracy was contrary tohuman nature,as human beings were seen to be inherently evil, violent and in need of a strong leader to restrain their destructive impulses. Many European monarchs held that their power had beenordained by Godand that questioning their right to rule was tantamount toblasphemy.

These conventional views were challenged at first by a relatively small group of Enlightenmentintellectuals,who believed that human affairs should be guided byreasonand principles of liberty and equality. They argued thatall people are created equaland therefore political authority cannot be justified on the basis of noble blood, a supposed privileged connection to God or any other characteristic that is alleged to make one person superior to others. They further argued that governments exist to serve the people—not vice versa—and that laws should apply to those who govern as well as to the governed (a concept known asrule of law).

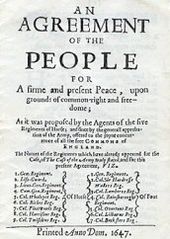

Some of these ideas began to be expressed in England in the 17th century.[5]There wasrenewed interest in Magna Carta,[11]and passage of thePetition of Rightin 1628 andHabeas Corpus Actin 1679 established certain liberties for subjects. The idea of a political party took form with groups debating rights to political representation during thePutney Debatesof 1647. After theEnglish Civil Wars(1642–1651) and theGlorious Revolutionof 1688, theBill of Rightswas enacted in 1689, which codified certain rights and liberties. The Bill set out the requirement for regular elections, rules for freedom of speech in Parliament and limited the power of the monarch, ensuring that, unlike almost all of Europe at the time,royal absolutismwould not prevail.[12][13]This led to significant social change in Britain in terms of the position of individuals in society and the growing power ofParliamentin relation to themonarch.[14][15]

By the late 18th century, leading philosophers of the day had published works that spread around the European continent and beyond. One of the most influential of these philosophers was English empiricistJohn Locke,who refutedmonarchical absolutismin hisTwo Treatises of Government.According to Locke, individuals entered into asocial contractwith astate,surrendering some of their liberties in exchange for the protection of theirnatural rights.Locke advanced that governments were only legitimate if they maintained theconsent of the governedand that citizens had theright to instigate a rebellionagainst their government if that government acted against their interests. These ideas and beliefs influenced theAmerican Revolutionand theFrench Revolution,which gave birth to the philosophy ofliberalismand instituted forms of government that attempted to put the principles of the Enlightenment philosophers into practice.

When the first prototypical liberal democracies were founded, the liberals themselves were viewed as an extreme and rather dangerous fringe group that threatened international peace and stability. The conservativemonarchistswho opposed liberalism and democracy saw themselves as defenders of traditional values and the natural order of things and their criticism of democracy seemed vindicated whenNapoleon Bonapartetook control of the youngFrench Republic,reorganized it into thefirst French Empireand proceeded to conquer most of Europe. Napoleon was eventually defeated and theHoly Alliancewas formed in Europe to prevent any further spread of liberalism or democracy. However, liberal democratic ideals soon became widespread among the general population and over the 19th century traditional monarchy was forced on a continuous defensive and withdrawal. TheDominionsof theBritish Empirebecame laboratories for liberal democracy from the mid 19th century onward. In Canada, responsible government began in the 1840s and in Australia and New Zealand, parliamentary government elected bymale suffrageandsecret ballotwas established from the 1850s andfemale suffrageachieved from the 1890s.[16]

Reforms and revolutions helped move most European countries towards liberal democracy. Liberalism ceased being a fringe opinion and joined the political mainstream. At the same time, a number of non-liberal ideologies developed that took the concept of liberal democracy and made it their own. The political spectrum changed; traditional monarchy became more and more a fringe view and liberal democracy became more and more mainstream. By the end of the 19th century, liberal democracy was no longer only a liberal idea, but an idea supported by many different ideologies. AfterWorld War Iand especially afterWorld War II,liberal democracy achieved a dominant position among theories of government and is now endorsed by the vast majority of the political spectrum.[citation needed]

Although liberal democracy was originally put forward by Enlightenment liberals, the relationship between democracy and liberalism has been controversial since the beginning and was problematized in the 20th century.[18]In his bookFreedom and Equality in a Liberal Democratic State,Jasper Doomen posited that freedom and equality are necessary for a liberal democracy.[19]In his bookThe End of History and the Last Man,Francis Fukuyamasays that since theFrench Revolution,liberal democracy has repeatedly proven to be a fundamentally better system (ethically, politically, economically) than any of the alternatives, and that democracy will become more and more prevalent in the long term, although it may suffer temporary setbacks.[20][21]The research instituteFreedom Housetoday simply defines liberal democracy as an electoral democracy also protectingcivil liberties.

Rights and freedoms

[edit]Political freedom is a centralconceptinhistoryand political thought and one of the most important features ofdemocraticsocieties.[22]Political freedom was described as freedom from oppression[23]or coercion,[24]the absence of disabling conditions for an individual and the fulfillment of enabling conditions,[25]or the absence of life conditions of compulsion, e.g. economic compulsion, in a society.[26]Although political freedom is often interpretednegativelyas the freedom from unreasonable external constraints on action,[27]it can also refer to thepositiveexercise of rights,capacitiesand possibilities for action and the exercise of social or group rights.[28]The concept can also include freedom from internal constraints on political action or speech (e.g. socialconformity,consistency, or inauthentic behaviour).[29]The concept of political freedom is closely connected with the concepts ofcivil libertiesandhuman rights,which in democratic societies are usually afforded legal protection from thestate.

Laws in liberal democracies may limit certain freedoms. The common justification for these limits is that they are necessary to guarantee the existence of democracy, or the existence of the freedoms themselves. For example, democratic governments may impose restrictions on free speech, with examples includingHolocaust denialandhate speech.Somediscriminatorybehavior may be prohibited. For example,public accommodations in the United Statesmay not discriminate on the basis of "race, color, religion, or national origin." There are various legal limitations such ascopyrightand laws againstdefamation.There may be limits on anti-democratic speech, on attempts to underminehuman rightsand on the promotion or justification ofterrorism.In the United States more than in Europe, during theCold Warsuch restrictions applied tocommunists.Now they are more commonly applied to organizations perceived as promoting terrorism or the incitement of group hatred. Examples includeanti-terrorism legislation,the shutting down ofHezbollahsatellite broadcasts and some laws againsthate speech.Critics[who?]claim that these limitations may go too far and that there may be no due and fair judicial process. Opinion is divided on how far democracy can extend to include the enemies of democracy in the democratic process.[citation needed]If relatively small numbers of people are excluded from such freedoms for these reasons, a country may still be seen as a liberal democracy. Some argue that this is only quantitatively (not qualitatively) different from autocracies that persecute opponents, since only a small number of people are affected and the restrictions are less severe, but others emphasize that democracies are different. At least in theory, opponents of democracy are also allowed due process under the rule of law.

Since it is possible to disagree over which rights are considered fundamental, different countries may treat particular rights in different ways. For example:

- The constitutions of Canada, India, Israel, Mexico and the United States guarantee freedom fromdouble jeopardy,a right not provided in some other legal systems.

- Legal systems that use politically elected court jurors, such asSweden,view a (partly) politicized court system as a main component of accountable government. Other democracies employtrial by jurywith the intent of shielding against the influence of politicians over trials.

Liberal democracies usually haveuniversal suffrage,granting alladultcitizens the right to vote regardless ofethnicity,sex,property ownership, race, age, sexuality,gender,income, social status, or religion. However, historically some countries regarded as liberal democracies have had a morelimited franchise.Even today, some countries, considered to be liberal democracies, do not have truly universal suffrage. In some countries, members of political organizations with connections to historical totalitarian governments (for example formerly predominant communist,fascistorNazigovernments in some European countries) may be deprived of the vote and the privilege of holding certain jobs. In the United Kingdom people serving long prison sentences are unable to vote, a policy which has been ruled a human rights violation by theEuropean Court of Human Rights.[30]A similar policy is also enacted in most of the United States.[31]According to a study by Coppedge and Reinicke, at least 85% of democracies provided foruniversal suffrage.[32]Many nationsrequire positive identification before allowing people to vote. For example, in the United States two thirds of the states require their citizens to provide identification to vote, which also provide state IDs for free.[33]The decisions made through elections are made by those who are members of the electorate and who choose toparticipatebyvoting.

In 1971,Robert Dahlsummarized the fundamental rights and freedoms shared by all liberal democracies as eight rights:[34]

- Freedom to form and join organizations.

- Freedom of expression.

- Right to vote.

- Right to run for public office.

- Right of political leaders to compete for support and votes.

- Freedom of alternative sources of information

- Free and fair elections.

- Right to control government policy through votes and other expressions of preference.

Preconditions

[edit]For a political regime to be considered a liberal democracy it must contain in its governing over a nation-state the provision of civil rights- the non-discrimination in the provision of public goods such as justice, security, education and health- in addition to, political rights- the guarantee of free and fair electoral contests, which allow the winners of such contests to determine policy subject to the constraints established by other rights, when these are provided- and property rights- which protect asset holders and investors against expropriation by the state or other groups. In this way, liberal democracy is set apart from electoral democracy, as free and fair elections – the hallmark of electoral democracy – can be separated from equal treatment and non-discrimination – the hallmarks of liberal democracy. In liberal democracy, an elected government cannot discriminate against specific individuals or groups when it administers justice, protects basic rights such as freedom of assembly and free speech, provides for collective security, or distributes economic and social benefits.[35] According to Seymour Martin Lipset, although they are not part of the system of government as such, a modicum ofindividualandeconomic freedoms,which result in the formation of a significantmiddle classand a broad and flourishingcivil society,are seen as pre-conditions for liberal democracy.[36]

For countries without a strong tradition of democratic majority rule, the introduction of free elections alone has rarely been sufficient to achieve a transition from dictatorship to democracy; a wider shift in the political culture and gradual formation of the institutions of democratic government are needed. There are various examples—for instance, inLatin America—of countries that were able to sustain democracy only temporarily or in a limited fashion until wider cultural changes established the conditions under which democracy could flourish.[citation needed]

One of the key aspects of democratic culture is the concept of aloyal opposition,where political competitors may disagree, but they must tolerate one another and acknowledge the legitimate and important roles that each play. This is an especially difficult cultural shift to achieve in nations where transitions of power have historically taken place through violence. The term means in essence that all sides in a democracy share a common commitment to its basic values. The ground rules of the society must encourage tolerance and civility in public debate. In such a society, the losers accept the judgement of the voters when the election is over and allow for thepeaceful transfer of power.According to Cas Mudde andCristóbal Rovira,this is tied to another key concept of democratic cultures, the protection of minorities,[37]where the losers are safe in the knowledge that they will neither lose their lives nor their liberty and will continue to participate in public life. They are loyal not to the specific policies of the government, but to the fundamental legitimacy of the state and to the democratic process itself.

One requirement of liberal democracy is political equality amongst voters (ensuring that all voices and all votes count equally) and that these can properly influence government policy, requiring quality procedure and quality content of debate that provides an accountable result, this may apply within elections or to procedures between elections. This requires universal, adult suffrage; recurring, free elections, competitive and fair elections; multiple political parties and a wide variety of information so that citizens can rationally and effectively put pressure onto the government, including that it can be checked, evaluated and removed. This can include or lead to accountability, responsiveness to the desires of citizens, the rule of law, full respect of rights and implementation of political, social and economic freedom.[38]Other liberal democracies consider the requirement of minority rights and preventing tyranny of the majority. One of the most common ways is by actively preventing discrimination by the government (bill of rights) but can also include requiring concurrent majorities in several constituencies (confederalism); guaranteeing regional government (federalism); broad coalition governments (consociationalism) or negotiating with other political actors, such as pressure groups (neocorporatism).[39]These split political power amongst many competing and cooperating actors and institutions by requiring the government to respect minority groups and give them their positive freedoms, negotiate across multiple geographical areas, become more centrist among cooperative parties and open up with new social groups.

In a new study published inNature Human Behaviour,Damian J. Ruck and his co-authors take a major step toward resolving this long-standing and seemingly irresolvable debate about whether culture shapes regimes or regimes shape culture. This study resolves the debate in favor of culture's causal primacy and shows that it is the civic and emancipative values (liberty,impartialityandcontractarianism) among a country's citizens that give rise to democratic institutions, not vice versa.[40][41]

Liberal democracies around the world

[edit]

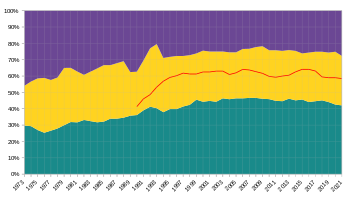

Several organizations and political scientists maintain lists of free and unfree states, both in the present and going back a couple centuries. Of these, the best known may be the Polity Data Set[43]and that produced byFreedom HouseandLarry Diamond.

There is agreement amongst several intellectuals and organizations such as Freedom House that the states of theEuropean Union(with the exception ofPolandandHungary),United Kingdom,Norway,Iceland,Switzerland,Japan,Argentina,Brazil,Chile,South Korea,Taiwan,theUnited States,India,Canada,[44][45][46][47][48]Uruguay,Costa Rica,Israel,South Africa,Australia,andNew Zealand[49]are liberal democracies. Liberal democracies are susceptible todemocratic backslidingand this is taking place or has taken place in several countries, including, but not limited to, theUnited States,Poland,Hungary,andIsrael.[6]

Freedom House considers many of the officially democratic governments inAfricaand the formerSoviet Unionto be undemocratic in practice, usually because the sitting government has a strong influence over election outcomes. Many of these countries are in a state of considerable flux.

Officially non-democratic forms of government, such as single-party states and dictatorships, are more common inEast Asia,theMiddle EastandNorth Africa.

The 2019Freedom in the Worldreport noted a fall in the number of countries with liberal democracies over the 13 years from 2005 to 2018, citing declines in 'political rights and civil liberties'.[50]The 2020[51]and 2021[52]reports document further reductions in the number of free countries in the world.

Types

[edit]Proportional vs. plurality representation

[edit]Plurality voting systemaward seats according to regional majorities. The political party or individual candidate who receives the most votes, wins the seat which represents that locality. There are other democratic electoral systems, such as the various forms ofproportional representation,which award seats according to the proportion of individual votes that a party receives nationwide or in a particular region.

One of the main points of contention between these two systems is whether to have representatives who are able to effectively represent specific regions in a country, or to have all citizens' vote count the same, regardless of where in the country they happen to live.

Some countries, such asGermanyandNew Zealand,address the conflict between these two forms of representation by having two categories of seats in thelower houseof their national legislative bodies. The first category of seats is appointed according to regional popularity and the remainder are awarded to give the parties a proportion of seats that is equal—or as equal as practicable—to their proportion of nationwide votes. This system is commonly calledmixed member proportional representation.

TheAustralian Governmentincorporates both systems in having thepreferential votingsystem applicable to thelower houseandproportional representationby state in theupper house.This system is argued to result in a more stable government, while having a better diversity of parties to review its actions. The variousstate and territory governmentsin Australia employ a range of a different electoral systems.

Presidential vs. parliamentary systems

[edit]Apresidential systemis asystem of governmentof arepublicin which theexecutive branchis elected separately from thelegislative.Aparliamentary systemis distinguished by theexecutive branch of governmentbeing dependent on the direct or indirect support of theparliament,often expressed through avote of confidence.

The presidential system of democratic government has been adopted inLatin America,Africaand parts of the formerSoviet Union,largely by the example of theUnited States.Constitutional monarchies(dominated by elected parliaments) are present inNorthern Europeand some formercolonieswhich peacefully separated, such asAustraliaandCanada.Others have also arisen inSpain,East Asiaand a variety of small nations around the world. Former British territories such asSouth Africa,India,Irelandand theUnited Statesopted for different forms at the time of independence. The parliamentary system is widely used in theEuropean Unionand neighbouring countries.

Impact on economic growth

[edit]Recent academic studies have found that democratisation is beneficial for national growth. However, the effect of democratisation has not been studied as yet. The most common factors that determine whether a country's economy grows or not are the country's level of development and the educational level of its newly elected democratic leaders. As a result, there is no clear indication of how to determine which factors contribute to economic growth in a democratic country.[53]

However, there is disagreement regarding how much credit the democratic system can take for this growth. One observation is that democracy became widespread only after theIndustrial Revolutionand the introduction ofcapitalism.On the other hand, the Industrial Revolution started in England which was one of the most democratic nations for its time within its own borders, but this democracy was very limited and did not apply to the colonies which contributed significantly to the wealth.[54]

Several statistical studies support the theory that a higher degree of economic freedom, as measured with one of the severalIndices of Economic Freedomwhich have been used in numerous studies,[55]increaseseconomic growthand that this in turn increases general prosperity, reduces poverty and causesdemocratisation.This is a statistical tendency and there are individual exceptions like Mali, which is ranked as "Free" byFreedom House,but is aLeast Developed Country,or Qatar, which has arguably the highest GDP per capita in the world, but has never been democratic. There are also other studies suggesting that more democracy increases economic freedom, although a few find no or even a small negative effect.[56][57][58][59][60][61]

Some argue that economic growth due to its empowerment of citizens will ensure a transition to democracy in countries such as Cuba. However, other dispute this and even if economic growth has caused democratisation in the past, it may not do so in the future. Dictators may now have learned how to have economic growth without this causing more political freedom.[62][63]

A high degree of oil or mineral exports is strongly associated with nondemocratic rule. This effect applies worldwide and not only to the Middle East. Dictators who have this form of wealth can spend more on their security apparatus and provide benefits which lessen public unrest. Also, such wealth is not followed by the social and cultural changes that may transform societies with ordinary economic growth.[64]

A 2006 meta-analysis found that democracy has no direct effect on economic growth. However, it has strong and significant indirect effects which contribute to growth. Democracy is associated with higher humancapital accumulation,lowerinflation,lower political instability and highereconomic freedom.There is also some evidence that it is associated with larger governments and more restrictions on international trade.[65]

If leaving outEast Asia,then during the last forty-five years poor democracies have grown their economies 50% more rapidly than nondemocracies. Poor democracies such as the Baltic countries, Botswana, Costa Rica, Ghana and Senegal have grown more rapidly than nondemocracies such as Angola, Syria, Uzbekistan and Zimbabwe.[9]

Of the eighty worst financial catastrophes during the last four decades, only five were in democracies. Similarly, poor democracies are half likely as non-democracies to experience a 10 per cent decline in GDP per capita over the course of a single year.[9]

Justifications and support

[edit]Increased political stability

[edit]Several key features of liberal democracies are associated with political stability, including economic growth, as well as robust state institutions that guarantee free elections, therule of law,and individual liberties.[7]

One argument for democracy is that by creating a system where the public can remove administrations, without changing the legal basis for government, democracy aims at reducing political uncertainty and instability and assuring citizens that however much they may disagree with present policies, they will be given a regular chance to change those who are in power, or change policies with which they disagree. This is preferable to a system where political change takes place through violence.[citation needed]

One notable feature of liberal democracies is that their opponents (those groups who wish to abolish liberal democracy) rarely win elections. Advocates use this as an argument to support their view that liberal democracy is inherently stable and can usually only be overthrown by external force, while opponents argue that the system is inherently stacked against them despite its claims to impartiality. In the past, it was feared that democracy could be easily exploited by leaders with dictatorial aspirations, who could get themselves elected into power. However, the actual number of liberal democracies that have elected dictators into power is low. When it has occurred, it is usually after a major crisis has caused many people to doubt the system or in young/poorly functioning democracies. Some possible examples includeAdolf Hitlerduring theGreat DepressionandNapoleon III,who became first President of theSecond French Republicand later Emperor.[citation needed]

Effective response in wartime

[edit]By definition, a liberal democracy implies that power is not concentrated. One criticism is that this could be a disadvantage for a state inwartime,when a fast and unified response is necessary. The legislature usually must give consent before the start of an offensive military operation, although sometimes the executive can do this on its own while keeping the legislature informed. If the democracy is attacked, then no consent is usually required for defensive operations. The people may vote against aconscriptionarmy.

However, actual research shows that democracies are more likely to win wars than non-democracies. One explanation attributes this primarily to "the transparency of thepolities,and the stability of their preferences, once determined, democracies are better able to cooperate with their partners in the conduct of wars ". Other research attributes this to superior mobilisation of resources or selection of wars that the democratic states have a high chance of winning.[66]

Stam andReiteralso note that the emphasis on individuality within democratic societies means that their soldiers fight with greater initiative and superior leadership.[67]Officers in dictatorships are often selected for political loyalty rather than military ability. They may be exclusively selected from a small class or religious/ethnic group that support the regime. The leaders in nondemocracies may respond violently to any perceived criticisms or disobedience. This may make the soldiers and officers afraid to raise any objections or do anything without explicit authorisation. The lack of initiative may be particularly detrimental in modern warfare. Enemy soldiers may more easily surrender to democracies since they can expect comparatively good treatment. In contrast, Nazi Germany killed almost 2/3 of the captured Soviet soldiers and 38% of the American soldiers captured by North Korea in theKorean Warwere killed.

Better information on and corrections of problems

[edit]A democratic system may provide better information for policy decisions. Undesirable information may more easily be ignored in dictatorships, even if this undesirable or contrarian information provides early warning of problems.Anders Chydeniusput forward the argument forfreedom of the pressfor this reason in 1776.[68]The democratic system also provides a way to replace inefficient leaders and policies, thus problems may continue longer and crises of all kinds may be more common in autocracies.[9]

Reduction of corruption

[edit]Research by theWorld Banksuggests that political institutions are extremely important in determining the prevalence ofcorruption:(long term) democracy, parliamentary systems, political stability and freedom of the press are all associated with lower corruption.[8]Freedom of information legislationis important foraccountabilityandtransparency.The IndianRight to Information Act"has already engendered mass movements in the country that is bringing the lethargic, often corrupt bureaucracy to its knees and changing power equations completely".[69]

Better use of resources

[edit]Democracies can put in place better education, longer life expectancy, lower infant mortality, access to drinking water and better health care than dictatorships. This is not due to higher levels of foreign assistance or spending a larger percentage of GDP on health and education, as instead the available resources are managed better.[9]

Prominent economistAmartya Senhas noted that no functioning democracy has ever suffered a large scalefamine.[70]Refugee crises almost always occur in non-democracies. From 1985 to 2008, the eighty-seven largest refugee crises occurred in autocracies.[9]

Health and human development

[edit]Democracy correlates with a higher score on theHuman Development Indexand a lower score on the human poverty index.

Several health indicators (life expectancy and infant and maternal mortality) have a stronger and more significant association with democracy than they have with GDP per capita, rise of the public sector or income inequality.[10]

In the post-communist nations, after an initial decline those that are the most democratic have achieved the greatest gains in life expectancy.[71]

Democratic peace theory

[edit]Numerous studies using many different kinds of data, definitions and statistical analyses have found support for the democratic peace theory.[citation needed]The original finding was that liberal democracies have never made war with one another. More recent research has extended the theory and finds that democracies have fewmilitarized interstate disputescausing less than 1,000 battle deaths with one another, that those militarized interstate disputes that have occurred between democracies have caused few deaths and that democracies have fewcivil wars.[72][73]There are various criticisms of the theory, including at least as many refutations as alleged proofs of the theory, some 200 deviant cases, failure to treat democracy as a multidimensional concept and that correlation is not causation.[74][page needed]

Minimization of political violence

[edit]Rudolph Rummel'sPower Killssays that liberal democracy, among all types of regimes, minimizes political violence and is a method of nonviolence. Rummel attributes this firstly to democracy instilling an attitude of tolerance of differences, an acceptance of losing and a positive outlook towards conciliation and compromise.[75]

A study published by the British Academy, onViolence and Democracy,[76]argues that in practice, liberal democracy has not stopped those running the state from exerting acts of violence both within and outside their borders. The paper also argues that police killings, profiling of racial and religious minorities, online surveillance, data collection, or media censorship are a couple of ways in which successful states maintain a monopoly on violence.

Objections and criticism

[edit]Campaign costs

[edit]In Athenian democracy, some public offices were randomly allocated to citizens, in order to inhibit the effects of plutocracy. Aristotle described the law courts in Athens which were selected by lot as democratic[77]and described elections as oligarchic.[78]

Political campaigning in representative democracies can favor the rich due to campaign costs, a form ofplutocracywhere only a very small number of wealthy individuals can actually affect government policy in their favor and towardplutonomy.[79]Stringentcampaign financelaws can correct this perceived problem.[citation needed]

Other studies predicted that the global trend toward plutonomies would continue, for various reasons, including "capitalist-friendly governments and tax regimes".[80]However, they also say that, since "political enfranchisement remains as was—one person, one vote, at some point it is likely that labor will fight back against the rising profit share of the rich and there will be a political backlash against the rising wealth of the rich."[81]

EconomistSteven Levittsays in his bookFreakonomicsthat campaign spending is no guarantee of electoral success. He compared electoral success of the same pair of candidates running against one another repeatedly for the same job, as often happens in United States congressional elections, where spending levels varied. He concludes:

- A winning candidate can cut his spending in half and lose only 1 percent of the vote. Meanwhile, a losing candidate who doubles his spending can expect to shift the vote in his favor by only that same 1 percent.[82]

On September 18, 2014, Martin Gilens and Benjamin I. Page's study concluded "Multivariate analysis indicates that economic elites and organized groups representing business interests have substantial independent impacts on U.S. government policy, while average citizens and mass-based interest groups have little or no independent influence. The results provide substantial support for theories of Economic-Elite Domination and for theories of Biased Pluralism, but not for theories of Majoritarian Electoral Democracy or Majoritarian Pluralism."[83]

Media

[edit]Critics of the role of the media in liberal democracies allege thatconcentration of media ownershipleads to major distortions of democratic processes. InManufacturing Consent: The Political Economy of the Mass Media,Edward S. HermanandNoam Chomskyargue via theirPropaganda Model[84]that the corporate media limits the availability of contesting views and assert this creates a narrow spectrum of elite opinion. This is a natural consequence, they say, of the close ties between powerfulcorporationsand the media and thus limited and restricted to the explicit views of those who can afford it.[85]Furthermore, the media's negative influence can be seen in social media where vast numbers of individuals seek their political information which is not always correct and may be controlled. For example, as of 2017, two-thirds (67%) of Americans report that they get at least some of their news from social media,[86]as well as a rising number of countries are exercising extreme control over the flow of information.[87]This may contribute to large numbers of individuals using social media platforms but not always gaining correct political information. This may cause conflict with liberal democracy and some of its core principles, such as freedom, if individuals are not entirely free since their governments are seizing that level of control on media sites. The notion that the media is used to indoctrinate the public is also shared by Yascha Mounk'sThe People Vs Democracywhich states that the government benefits from the public having a relatively similar worldview and that this one-minded ideal is one of the principles in which Liberal Democracy stands.[88]

Defenders responding to such arguments say that constitutionally protectedfreedom of speechmakes it possible for both for-profit and non-profit organisations to debate the issues. They argue that media coverage in democracies simply reflects public preferences and does not entail censorship. Especially with new forms of media such as the Internet, it is not expensive to reach a wide audience, if an interest in the ideas presented exists.

Limited voter turnout

[edit]Low voter turnout, whether the cause is disenchantment, indifference or contentment with the status quo, may be seen as a problem, especially if disproportionate in particular segments of the population. Although turnout levels vary greatly among modern democratic countries and in various types and levels of elections within countries, at some point low turnout may prompt questions as to whether the results reflect the will of the people, whether the causes may be indicative of concerns to the society in question, or in extreme cases thelegitimacyof the electoral system.

Get out the votecampaigns, either by governments or private groups, may increase voter turnout, but distinctions must be made between general campaigns to raise the turnout rate and partisan efforts to aid a particular candidate, party or cause. Other alternatives include increased use ofabsentee ballots,or other measures to ease or improve the ability to vote, includingelectronic voting.

Several nations have forms ofcompulsory voting,with various degrees of enforcement. Proponents argue that this increases the legitimacy—and thus also popular acceptance—of the elections and ensures political participation by all those affected by the political process and reduces the costs associated with encouraging voting. Arguments against include restriction of freedom, economic costs of enforcement, increased number of invalid and blank votes and random voting.[89]

Bureaucracy

[edit]A persistentlibertarianandmonarchistcritique of democracy is the claim that it encourages the elected representatives to change the law without necessity and in particular to pour forth a flood of new laws (as described inHerbert Spencer'sThe Man Versus The State). This is seen as pernicious in several ways. New laws constrict the scope of what were previously private liberties. Rapidly changing laws make it difficult for a willing non-specialist to remain law-abiding. This may be an invitation for law-enforcement agencies to misuse power. The claimed continual complication of the law may be contrary to a claimed simple and eternalnatural law—although there is no consensus on what this natural law is, even among advocates. Supporters of democracy point to the complex bureaucracy and regulations that has occurred in dictatorships, like many of the former communist states.

The bureaucracy in liberal democracies is often criticised for a claimed slowness and complexity of their decision-making. The term "red tape"is a synonym of slow bureaucratic functioning that hinders quick results in a liberal democracy.

Short-term focus

[edit]By definition, modern liberal democracies allow for regular changes of government. That has led to a common criticism of their short-term focus. In four or five years the government will face a new election and it must think of how it will win that election. That would encourage a preference for policies that will bring short term benefits to the electorate (or to self-interested politicians) before the next election, rather than unpopular policy with longer term benefits. This criticism assumes that it is possible to make long term predictions for a society, somethingKarl Popperhas criticised ashistoricism.

Besides the regular review of governing entities, short-term focus in a democracy could also be the result of collective short-term thinking. For example, consider a campaign for policies aimed at reducing environmental damage while causing temporary increase in unemployment. However, this risk applies also to other political systems.

Majoritarianism

[edit]This sectionneeds additional citations forverification.(August 2012) |

Thetyranny of the majorityis the fear that a direct democratic government, reflecting the majority view, can take action that oppresses a particular minority. For instance, a minority holding wealth, property ownership or power (seeFederalist No. 10), or a minority of a certain racial and ethnic origin, class or nationality. Theoretically, the majority is a majority of all citizens. If citizens are not compelled by law to vote, it is usually a majority of those who choose to vote. If such of group constitutes a minority, then it is possible that a minority could in theory oppress another minority in the name of the majority. However, such an argument could apply to bothdirect democracyorrepresentative democracy.Severalde factodictatorships also have compulsory, but not "free and fair" voting in order to try to increase the legitimacy of the regime, such asNorth Korea.[90][91]

In her bookWorld on Fire,Yale Law SchoolprofessorAmy Chuaposits that "when free market democracy is pursued in the presence of a market-dominant minority, the almost invariable result is backlash. This backlash typically takes one of three forms. The first is a backlash against markets, targeting the market-dominant minority's wealth. The second is a backlash against democracy by forces favorable to the market-dominant minority. The third is violence, sometimesgenocidal,directed against the market-dominant minority itself ".[92]

Cases that have been cited as examples of a minority being oppressed by or in the name of the majority include[citation needed]the practice ofconscriptionand laws againsthomosexuality,pornography,andrecreational drug use.Homosexual acts were widely criminalised in democracies until several decades ago and in some democracies like Ghana, Kenya, Tanzania, Tunisia, Nigeria, and Malaysia, they still are, reflecting the religious or sexual mores of the majority. The Athenian democracy and the early United States practicedslavery,and even proponents of liberal democracy in the 17th and 18th century were often pro-slavery, which is contradictory of a liberal democracy. Another often quoted example of the "tyranny of the majority" is thatAdolf Hitlercame to power by "legitimate" democratic procedures. TheNazi Partygained the largest share of votes in the democraticWeimar Republicin 1933. However, his regime's large-scale human rights violations took place after the democratic system had been abolished. Furthermore, theWeimar Constitutionin an"emergency" allowed dictatorial powers and suspension of the essentials of the constitution itself without any vote or election.

Proponents of democracy make a number of defenses concerning "tyranny of the majority". One is to argue that the presence of aconstitutionprotecting the rights of all citizens in many democratic countries acts as a safeguard. Generally, changes in these constitutions require the agreement of asupermajorityof the elected representatives, or require a judge and jury to agree that evidentiary and procedural standards have been fulfilled by the state, or two different votes by the representatives separated by an election, or sometimes areferendum.These requirements are often combined. Theseparation of powersintolegislative branch,executive branchandjudicial branchalso makes it more difficult for a small majority to impose their will. This means a majority can still legitimately coerce a minority (which is still ethically questionable), but such a minority would be very small and as a practical matter it is harder to get a larger proportion of the people to agree to such actions.

Another argument is that majorities and minorities can take a markedly different shape on different issues. People often agree with the majority view on some issues and agree with a minority view on other issues. One's view may also change, thus the members of a majority may limit oppression of a minority since they may well in the future themselves be in a minority.

A third common argument is that despite the risks majority rule is preferable to other systems and the tyranny of the majority is in any case an improvement on a tyranny of a minority. All the possible problems mentioned above can also occur in non-democracies with the added problem that a minority can oppress the majority. Proponents of democracy argue that empirical statistical evidence strongly shows that more democracy leads to less internal violence and mass murder by the government. This is sometimes formulated asRummel's Law,which states that the less democratic freedom a people have, the more likely their rulers are to murder them.

Conservative criticism

[edit]Traditionalist conservativesargue that "liberal democracy is a dangerous betrayal of deeper sources of culture and civilization such as the family, the tribe, the nation, and the church."[93]

Marxist criticism

[edit]This section has multiple issues.Please helpimprove itor discuss these issues on thetalk page.(Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

|

Marxistsandcommunists,as well as some non-Marxistsocialistsandanarchists,argue that liberal democracy undercapitalismis constitutivelyclass-based and therefore can never be democratic orparticipatory.They refer to it as "bourgeoisdemocracy "because they say that ultimately, politicians fight mainly for the interests of the bourgeoisie.[94]As such, liberal democracy is said to represent "the rule of capital".[93]

According toKarl Marx,representation of the interests of different classes is proportional to the influence which a particular class can purchase (through bribes, transmission of propaganda through mass media, economic blackmail, donations for political parties and their campaigns and so on). Thus, the public interest in so-called liberal democracies is systematically corrupted by the wealth of those classes rich enough to gain the appearance of representation. Because of this, he said thatmulti-party democraciesunder capitalism are always distorted and anti-democratic, their operation merely furthering the class interests of the owners of the means of production, and the bourgeois class becomes wealthy through a drive to appropriate thesurplus-valueof the creative labours of the working class. This drive obliges the bourgeois class to amass ever-larger fortunes by increasing the proportion of surplus-value by exploiting the working class through capping workers' terms and conditions as close to poverty levels as possible. Incidentally, this obligation demonstrates the clear limit to bourgeois freedom even for the bourgeoisie itself. According to Marx, parliamentary elections are no more than a cynical, systemic attempt to deceive the people by permitting them, every now and again, to endorse one or other of the bourgeoisie's predetermined choices of which political party can best advocate the interests of capital. Once elected, he said that this parliament, as a dictatorship of the bourgeoisie, enacts regulations that actively support the interests of its true constituency, the bourgeoisie (such as bailing out Wall St investment banks; direct socialisation/subsidisation of business—GMH, US/Europeanagricultural subsidies;and even wars to guarantee trade in commodities such as oil).

Vladimir Leninonce argued that liberal democracy had simply been used to give an illusion of democracy whilst maintaining the dictatorship of thebourgeoisie,giving as an example the United States's representative democracy which he said consisted of "spectacular and meaningless duels between two bourgeois parties" led by "multimillionaires".[95]

Socialist and communist criticism

[edit]Some socialists, such asThe Leftparty in Germany,[96]say that liberal democracy is a dishonest farce used to keep the masses from realizing that their will is irrelevant in the political process. TheChinese Communist Partypolitical concept ofwhole-process people's democracycriticizes liberal democracy for excessively relying on procedural formalities without genuinely reflecting the interests of the people.[97]Under this primarily consequentialist concept, the most important criteria for a democracy is whether it can "solve the people's real problems", while a system in which "the people are awakened only for voting" is not truly democratic.[97]For example, the Chinese government's 2021 white paperChina: Democracy that Workscriticizes liberal democracy's shortcoming based on principles of whole process people's democracy.[98]

Vulnerabilities

[edit]Authoritarianism

[edit]Authoritarianism is perceived by many to be a direct threat to the liberalised democracy practised in many countries. According to American political sociologist and authorsLarry Diamond,Marc F. Plattner and Christopher Walker, undemocratic regimes are becoming more assertive.[99]They suggest that liberal democracies introduce more authoritarian measures to counter authoritarianism itself and cite monitoring elections and more control on media in an effort to stop the agenda of undemocratic views. Diamond, Plattner and Walker uses an example of China using aggressive foreign policy against western countries to suggest that a country's society can force another country to behave in a more authoritarian manner. In their book 'Authoritarianism Goes Global: The Challenge to Democracy' they claim that Beijing confronts the United States by building its navy and missile force and promotes the creation of global institutions designed to exclude American and European influence; as such authoritarian states pose a threat to liberal democracy as they seek to remake the world in their own image.[100]

Various authors have also analysed the authoritarian means that are used by liberal democracies to defend economic liberalism and the power of political elites.[101]

War

[edit]There are ongoing debates surrounding the effect that war may have on liberal democracy, and whether it cultivates or inhibits democratization.

War may cultivate democratization by "mobilizing the masses, and creating incentives for the state to bargain with the people it needs to contribute to the war effort".[102]An example of this may be seen in the extension ofsuffragein the UK afterWorld War I.

War may however inhibit democratization by "providing an excuse for the curtailment ofliberties".[102]

Terrorism

[edit]The examples and perspective in this sectionmay not represent aworldwide viewof the subject.(January 2014) |

Several studies[citation needed]have concluded that terrorism is most common in nations with intermediatepolitical freedom,meaning countries transitioning from autocratic governance to democracy. Nations with strong autocratic governments and governments that allow for more political freedom experience less terrorism.[103]

Populism

[edit]There is no one agreed upon definition of populism, with a broader definition settled upon following a conference at the London School of Economics in 1967.[104]Academically, the term "populism" faces criticism that it should be abandoned as a descriptor due to its vagueness.[105]It is typically not fundamentally undemocratic, but it is often anti-liberal. Many will agree on certain features that characterize populism and populists: a conflict between 'the people' and 'the elites', with populists siding with 'the people'[106]and strong disdain for opposition and negative media using labels such as 'fake news'.[107]

Populism is a form of majoritarianism, threatening some of the core principles of liberal democracy such as the rights of the individual. Examples of these can vary fromfreedom of movementvia control on immigration, or opposition to liberal social values such as gay marriage.[108]Populists do this by appealing to the feelings and emotions of the people whilst offering solutions - often vastly simplified - to complex problems.

Populism is a particular threat to the liberal democracy because it exploits the weaknesses of the liberal democratic system. A key weakness of liberal democracies highlighted in 'How Democracies Die',[109]is the conundrum that suppressing populist movements or parties can be seen to be illiberal. Another reason that populism is a threat to liberal democracy is because it exploits the inherent differences between 'Democracy' and 'Liberalism'.[110]For liberal democracy to be effective, a degree of compromise is required[111]as protecting the rights of the individual take precedence if they are threatened by the will of the majority, more commonly known as a tyranny of the majority. Majoritarianism is so ingrained in populism that this core value of a liberal democracy is under threat. This therefore brings into question how effectively liberal democracy can defend itself from populism.

According to Takis Papas in his workPopulism and Liberal Democracy: A Comparative and Theoretical Analysis,"democracy has two opposites, one liberal, the other populist". Whereas liberalism accepts a notion of society composed of multiple divisions, populism only acknowledges a society of 'the people' versus 'the elites'. The fundamental beliefs of the populist voter consist of: the belief that oneself is powerless and is a victim of the powerful; a "sense of enmity" rooted in "moral indignation and resentfulness"; and a "longing for future redemption" through the actions of a charismatic leader. Papas says this mindset results in a feeling of victimhood caused by the belief that the society is "made up of victims and perpetrators". Other characteristic of a populist voter is that they are "distinctively irrational" because of the "disproportionate role of emotions and morality" when making a political decision like voting. Moreover, through self-deception they are "wilfully ignorant". In addition, they are "intuitively… and unsettlingly principled" rather than a more "pragmatic" liberal voter.[112]

An example of a populist movement isthe 2016 Brexit campaign.[113]The role of the 'elite' in this circumstance was played by the EU and 'London-centric liberals',[114]while the Brexit campaign appealed to workers in industries such as agriculture who were allegedly worse off due to EU membership. This case study also illustrates the potential threat populism can pose to a liberal democracy with the movement heavily relying on disdain for the media. This was done by labeling criticism of Brexit as 'Project Fear'.

See also

[edit]- Constitutional liberalism

- Centrism

- Conservative liberalism

- Democratic backsliding

- Democratic ideals

- Economic liberalism

- Elective rights

- Good governance

- History of democracy

- Illiberal democracy

- Index of politics articles

- Jeffersonian democracy

- Neoliberalism

- Republicanism

- Social democracy

- Social liberalism

- Liberal conservatism

References

[edit]- ^He, Jiacheng (8 January 2022)."The Patterns of Democracy in Context of Historical Political Science".Chinese Political Science Review.7(1). Springer Science and Business Media LLC: 111–139.doi:10.1007/s41111-021-00201-5.ISSN2365-4244.S2CID256470545.

- ^abJacobs, Lawrence R.; Shapiro, Robert Y. (1994)."Studying Substantive Democracy".PS: Political Science and Politics.27(1): 9–17.doi:10.2307/420450.ISSN1049-0965.JSTOR420450.S2CID153637162.

- ^Cusack, Simone; Ball, Rachel (July 2009).Eliminating Discrimination and Ensuring Substantive Equality(PDF)(Report). Public Interest Law Clearing House and Human Rights Law Resource Centre Ltd. Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 6 June 2022.Retrieved12 June2024.

- ^"What is substantive equality?". Equal Opportunity Commission, Government of Western Australia. November 2014. Retrieved 28 October 2018

- ^abKopstein, Jeffrey; Lichbach, Mark; Hanson, Stephen E., eds. (2014).Comparative Politics: Interests, Identities, and Institutions in a Changing Global Order(4, revised ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 37–39.ISBN978-1139991384.Archivedfrom the original on 30 June 2020.Retrieved6 June2020.

Britain pioneered the system of liberal democracy that has now spread in one form or another to most of the world's countries

- ^abAnna Lührmann, Seraphine F. Maerz, Sandra Grahn, Nazifa Alizada, Lisa Gastaldi, Sebastian Hellmeier, Garry Hindle and Staffan I. Lindberg. 2020. Autocratization Surges – Resistance Grows. Democracy Report 2020. Varieties of Democracy Institute (V-Dem).[1]Archived18 December 2021 at theWayback Machine

- ^abCarugati, Federica (2020)."Democratic Stability: A Long View".Annual Review of Political Science.23:59–75.doi:10.1146/annurev-polisci-052918-012050.

In sum, this literature suggests that stable democracies look very much like liberal democracies, whose critical features are...

- ^abDaniel Lederman, Normal Loaza, Rodrigo Res Soares (November 2001)."Accountability and Corruption: Political Institutions Matter".World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No. 2708.SSRN632777."Accountability and Corruption: Political Institutions Matter by Daniel Lederman, Norman Loayza, Rodrigo R. Soares:: SSRN".SSRN632777.Archived from the original on 19 January 2021.Retrieved17 June2023.

{{cite web}}:CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link).Retrieved 19 February 2006. - ^abcdefHalperin, Morton; Siegle, Joseph T.; Weinstein, Michael."The Democracy Advantage: How Democracies Promote Prosperity and Peace".Carnegie Council.Archived fromthe originalon 28 June 2006.

- ^abFranco, Álvaro; Álvarez-Dardet, Carlos; Ruiz, Maria Teresa (2004)."Effect of democracy on health: ecological study (required)".British Medical Journal.329(7480): 1421–23.doi:10.1136/bmj.329.7480.1421.PMC535957.PMID15604165.

- ^"From legal document to public myth: Magna Carta in the 17th century".The British Library.Archivedfrom the original on 18 October 2017.Retrieved16 October2017;"Magna Carta: Magna Carta in the 17th Century".The Society of Antiquaries of London.Archivedfrom the original on 25 September 2018.Retrieved16 October2017.

- ^"Britain's unwritten constitution".British Library.Archivedfrom the original on 8 December 2015.Retrieved27 November2015.

The key landmark is the Bill of Rights (1689), which established the supremacy of Parliament over the Crown.... The Bill of Rights (1689) then settled the primacy of Parliament over the monarch's prerogatives, providing for the regular meeting of Parliament, free elections to the Commons, free speech in parliamentary debates, and some basic human rights, most famously freedom from 'cruel or unusual punishment'.

- ^"Constitutionalism: America & Beyond".Bureau of International Information Programs (IIP), U.S. Department of State. Archived fromthe originalon 24 October 2014.Retrieved30 October2014.

The earliest, and perhaps greatest, victory for liberalism was achieved in England. The rising commercial class that had supported the Tudor monarchy in the 16th century led the revolutionary battle in the 17th, and succeeded in establishing the supremacy of Parliament and, eventually, of the House of Commons. What emerged as the distinctive feature of modern constitutionalism was not the insistence on the idea that the king is subject to law (although this concept is an essential attribute of all constitutionalism). This notion was already well established in the Middle Ages. What was distinctive was the establishment of effective means of political control whereby the rule of law might be enforced. Modern constitutionalism was born with the political requirement that representative government depended upon the consent of citizen subjects.... However, as can be seen through provisions in the 1689 Bill of Rights, the English Revolution was fought not just to protect the rights of property (in the narrow sense) but to establish those liberties which liberals believed essential to human dignity and moral worth. The "rights of man" enumerated in the English Bill of Rights gradually were proclaimed beyond the boundaries of England, notably in the American Declaration of Independence of 1776 and in the French Declaration of the Rights of Man in 1789.

- ^"Citizenship 1625–1789".The National Archives.Archivedfrom the original on 11 January 2016.Retrieved22 January2016;"Rise of Parliament".The National Archives.Archivedfrom the original on 17 August 2018.Retrieved22 January2016.

- ^Heater, Derek (2006)."Emergence of Radicalism".Citizenship in Britain: A History.Edinburgh University Press. pp. 30–42.ISBN978-0748626724.

- ^Geoffrey Blainey (2004),A Very Short History of the World,Penguin Books,ISBN978-0143005599

- ^"War or Peace for Finland? Neoclassical Realist Case Study of Finnish Foreign Policy in the Context of the Anti-Bolshevik Intervention in Russia 1918–1920".Archivedfrom the original on 23 July 2020.Retrieved22 July2020.

- ^Schmitt, Carl (1985).The Crisis of Parliamentary Democracy.Cambridge: MIT Press. pp. 2, 8 (chapter 1).ISBN978-0262192408.

- ^Doomen, Jasper (2014).Freedom and Equality in a Liberal Democratic State.Brussels: Bruylant. pp. 88, 101.ISBN978-2802746232.

- ^Fukuyama, Francis (1989). "The End of History?".The National Interest(16): 3–18.ISSN0884-9382.JSTOR24027184.

- ^Glaser, Eliane (21 March 2014)."Bring Back Ideology: Fukuyama's 'End of History' 25 years On".The Guardian.Archivedfrom the original on 17 April 2019.Retrieved18 March2019.

- ^Hannah Arendt, "What is Freedom?",Between Past and Future: Eight Exercises in Political Thought,(New York: Penguin, 1993).

- ^Iris Marion Young, "Five Faces of Oppression",Justice and the Politics of Difference(Princeton University press, 1990), 39–65.

- ^Michael Sandel,Justice: What's the Right Thing to Do?(Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2010).

- ^Amartya Sen,Development as Freedom(Anchor Books, 2000).

- ^Karl Marx,"Alienated Labour" inEarly Writings.

- ^Isaiah Berlin,Liberty(Oxford 2004).

- ^Charles Taylor,"What's Wrong With Negative Liberty?",Philosophy and the Human Sciences: Philosophical Papers(Cambridge, 1985), 211–229.

- ^Ralph Waldo Emerson, "Self-Reliance";Nikolas Kompridis," Struggling Over the Meaning of Recognition: A Matter of Identity, Justice or Freedom? "inEuropean Journal of Political TheoryJuly 2007 vol. 6 no. 3 pp. 277–289.

- ^Factsheet – Prisoners' right to voteArchived7 August 2020 at theWayback MachineEuropean Court of Human Rights, April 2019.

- ^"Felon Voting Rights".National Conference of State Legislatures.Archivedfrom the original on 7 March 2016.Retrieved23 April2021.

- ^Coppedge, Michael; Reinicke, Wolfgang (1991).Measuring Polyarchy.New Brunswick: Transaction.

- ^"Voting requirements".USA Gov.Archivedfrom the original on 22 January 2021.Retrieved21 January2021.

- ^Dahl, Robert A. (1971).Polyarchy: participation and opposition.New Haven: Yale University Press.ISBN0-585-38576-9.OCLC49414698.Archivedfrom the original on 24 May 2022.Retrieved23 January2021.

- ^Mukand, S. W., & Rodrik, D. (2016). The Political Economy of Liberal Democracy. The Economic Journal, 130(627), 765–792.https://drodrik.scholar.harvard.edu/files/dani-rodrik/files/the_political_economy_of_liberal_democracy_june_2016.pdfArchived18 November 2022 at theWayback Machine

- ^Lipset, Seymour Martin (1959)."Some Social Requisites of Democracy: Economic Development and Political Legitimacy".The American Political Science Review.53(1): 69–105.doi:10.2307/1951731.ISSN0003-0554.JSTOR1951731.S2CID53686238.Archivedfrom the original on 9 February 2023.Retrieved25 January2021.

- ^Mudde, Cas;Rovira Kaltwasser, Cristóbal(2012).Populism in Europe and the Americas: threat or corrective for democracy?.Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.ISBN978-1-139-42423-3.OCLC795125118.

- ^Morlino L. (2004) "What is a 'good' democracy?", Demoocratization, 11(5), pp. 10-32. Available at:https://doi.org/10.1080/13510340412331304589

- ^Schmitter P.C. and Karl T.L. (1991) "What Democracy Is...and Is Not", Journal of Democracy, 2(3), pp. 75-88. Available at:https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.1991.0033.

- ^Ruck, Damian J.; Matthews, Luke J.; Kyritsis, Thanos; Atkinson, Quentin D.; Bentley, R. Alexander (2020). "The cultural foundations of modern democracies".Nature Human Behaviour.4(3): 265–269.doi:10.1038/s41562-019-0769-1.PMID31792400.S2CID256726148.

- ^Welzel, Christian (2020)."A cultural theory of regimes".Nature Human Behaviour.4(3): 231–232.doi:10.1038/s41562-019-0790-4.PMID31792403.S2CID256707649.

- ^List of Electoral Democracies FIW23Archived15 April 2023 at theWayback Machine(.XLSX), byFreedom House

- ^"Policy Data Set".Archivedfrom the original on 4 May 2020.Retrieved28 October2008.

- ^Benhabib, Seyla, ed. (1996).Democracy and difference: contesting the boundaries of the political.Princeton University Press.ISBN978-0691044781.

- ^Alain Gagnon,Intellectuals in liberal democracies: political influence and social involvement

- ^Yvonne Schmidt, Foundations of Civil and Political Rights in Israel and the Occupied Territories

- ^William S. Livingston, A Prospect of purple and orange democracy

- ^Mazie, Steven V. (2006).Israel's higher law: religion and liberal democracy in the Jewish state.Lexington Books.ISBN978-0739114858.

- ^Mulgan, Richard; Peter Aimer (2004)."chapter 1".Politics in New Zealand(3rd ed.). Auckland University Press. p. 17.ISBN1869403185.Archivedfrom the original on 22 September 2020.Retrieved26 June2009.

- ^"Freedom in the World: Democracy in Retreat".freedomhouse.org.Freedom House.Archivedfrom the original on 5 February 2019.Retrieved7 December2019.

- ^"Freedom in the World 2020"(PDF).Freedom House. 4 March 2020.Archived(PDF)from the original on 4 March 2020.Retrieved4 March2020.

- ^"Freedom in the World 2021"(PDF).Freedom House. 3 March 2021.Archived(PDF)from the original on 26 December 2021.Retrieved3 March2021.

- ^The Effects of Democracy on Economic Growth"The Effects of Democracy on Economic Growth".2022.Archivedfrom the original on 26 January 2022.Retrieved8 October2022.

- ^"The economic impact of colonialism".2017.Archivedfrom the original on 17 August 2022.Retrieved8 October2022.

- ^Free the World.Published Work Using Economic Freedom of the World ResearchArchived14 May 2011 at theWayback Machine.Retrieved 19 February 2006.

- ^Bergren, Niclas (2002)."The Benefits of Economic Freedom: A Survey"(PDF).Archived from the original on 28 June 2007.

{{cite web}}:CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^John W. Dawson, (1998)."Review of Robert J. Barro, Determinants of Economic Growth: A Cross-Country Empirical Study"Archived20 April 2006 at theWayback Machine.Economic History Services.Retrieved 19 February 2006.

- ^W. Ken Farr, Richard A. Lord, J. Larry Wolfenbarger, (1998)."Economic Freedom, Political Freedom, and Economic Well-Being: A Causality Analysis"(PDF).Archived from the original on 3 February 2007.Retrieved11 April2005.

{{cite web}}:CS1 maint: unfit URL (link).Cato Journal,Vol 18, No 2. - ^Wenbo Wu, Otto A. Davis, (2003). "Economic Freedom and Political FreedomArchived24 May 2006 at theWayback Machine",Encyclopedia of Public Choice.Carnegie Mellon University,National University of Singapore.

- ^Ian Vásquez, (2001)."Ending Mass Poverty"Archived24 May 2011 at theWayback Machine.Cato Institute.Retrieved 19 February 2006.

- ^Susanna Lundström, (April 2002)."The Effects of Democracy on Different Categories of Economic Freedom"Archived24 May 2006 at theWayback Machine.Retrieved 19 February 2006.

- ^Bueno de Mesquita, Bruce; Downs, George W. (September–October 2005)."Development and Democracy".Foreign Affairs.84(September/October 2005). Council on Foreign Relations.Archivedfrom the original on 22 October 2018.Retrieved22 October2018.

- ^Single, Joseph T.; Weinstein, Michael M.; Halperin, Morton H. (28 September 2004)."Why Democracies Excel".New York Times.Archivedfrom the original on 13 November 2016.Retrieved2 March2017.

- ^Ross, Michael Lewin (2001). "Does Oil Hinder Democracy?".World Politics.53(3): 325–61.doi:10.1353/wp.2001.0011.S2CID18404.

- ^Doucouliagos, H., Ulubasoglu, M (2006). "Democracy and Economic Growth: A meta-analysis".School of Accounting, Economics and Finance Deakin University Australia.

{{cite journal}}:CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^Ajin Choi, (2004). "Democratic Synergy and Victory in War, 1816–1992".International Studies Quarterly,Volume 48, Number 3, September 2004, pp. 663–82 (20).doi:10.1111/j.0020-8833.2004.00319.x

- ^Dan, Reiter; Stam, Allan C. (2002).Democracies at War.Princeton University Press. pp.64–70.ISBN0691089485.

- ^Luoma, Jukka."Helsingin Sanomat – International Edition".Archived fromthe originalon 20 November 2007.Retrieved26 November2007.

- ^"Right to Information Act India's magic wand against corruption".AsiaMedia.Archived fromthe originalon 26 September 2008.Retrieved28 October2008.

- ^Sen, Amartya(1999)."Democracy as a Universal Value".Journal of Democracy.10(3): 3–17.doi:10.1353/jod.1999.0055.Archived fromthe originalon 27 April 2006 – via Johns Hopkins University Press Project MUSE.

- ^McKee, Marin; Ellen Nolte (2004)."Lessons from health during the transition from communism".British Medical Journal.329(7480): 1428–29.doi:10.1136/bmj.329.7480.1428.PMC535963.PMID15604170.

- ^Hegre, Håvard; Ellingsen, Tanja; Gates, Scott; Gleditsch, Nils Petter (2001)."Towards A Democratic Civil Peace? Opportunity, Grievance, and Civil War 1816–1992".American Political Science Review.95:33–48.doi:10.1017/s0003055401000119.S2CID7521813.Archived fromthe originalon 9 February 2006.

- ^Ray, James Lee (2003).A Lakatosian View of the Democratic Peace Research Program From Progress in International Relations Theory, edited by Colin and Miriam Fendius Elman(PDF).MIT Press. Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 25 June 2006.

- ^Haas, Michael (2014).Deconstructing the "democratic peace": how a research agenda boomeranged.Los Angeles, CA: Publishinghouse for Scholars.ISBN9780983962625.

- ^R. J. Rummel,Power Kills.1997. p.6.

- ^"Violence and Democracy"(PDF).The British Academy.September 2019.Archived(PDF)from the original on 7 March 2023.Retrieved25 January2021.

- ^Aristotle, Politics 2.1273b

- ^Aristotle, Politics 4.1294b

- ^Draper, Hal (1974)."Marx on Democratic Forms of Government".The Socialist Register.11.Archivedfrom the original on 5 August 2019.Retrieved22 October2018.

- ^Kapur, Ajay, Niall Macleod, Narendra Singh: "Plutonomy: Buying Luxury, Explaining Global Imbalances", Citigroup, Equity Strategy, Industry Note: October 16, 2005. p. 9f.

- ^Kapur, Ajay, Niall Macleod, Narendra Singh: "Revisiting Plutonomy: The Rich Getting Richer", Citigroup, Equity Strategy, Industry Note: March 5, 2006. p. 10.

- ^Levitt, Steven;Dubner, Stephen J.(2006).Freakonomics: A Rogue Economist Explores the Hidden Side of Everything.HarperCollins.p. 14.ISBN978-0061245138.Archivedfrom the original on 22 September 2020.Retrieved6 June2020.

- ^Gilens, M., & Page, B. (2014). Testing Theories of American Politics: Elites, Interest Groups, and Average Citizens.Perspectives on Politics,12(3), 564–81.doi:10.1017/S1537592714001595

- ^Edward S. Herman"The Propaganda Model Revisited"Archived6 January 2012 at theWayback Machine,Monthly Review,July 1996, as reproduced on the Chomsky.info website

- ^James Curran andJean SeatonPower Without Responsibility: the Press and Broadcasting in Britain,London: Routledge, 1997, p. 1

- ^Shearer, Elisa; Gottfried, Jeffrey (7 September 2017)."News Use Across Social Media Platforms 2017".Pew Research Center's Journalism Project.Archivedfrom the original on 16 March 2021.Retrieved14 January2021.

- ^Chapman, Terri (27 October 2019)."Liberal democracy is under threat from digitisation as govts, tech firms gain more power".ThePrint.Archivedfrom the original on 15 April 2021.Retrieved14 January2021.

- ^Girard, Raphaël (2019)."Yascha Mounk, The People vs. Democracy: Why Our Freedom Is in Danger and How to Save It, Cambridge, MA and London: Harvard University Press, 2018, 400 pp, hb £21.95".The Modern Law Review.82(1): 196–200.doi:10.1111/1468-2230.12397.ISSN1468-2230.S2CID149968721.Archivedfrom the original on 20 April 2021.Retrieved25 January2021.

- ^"International IDEA | Compulsory Voting".Idea.int. Archived fromthe originalon 12 June 2009.Retrieved28 October2008.

- ^"DPRK Holds Election of Local and National Assemblies".People's Korea.Archived fromthe originalon 10 May 2012.Retrieved28 June2008.

- ^"The Parliamentary System of the Democratic People's Republic of Korea"(PDF).Constitutional and Parliamentary Information.Association of Secretaries General of Parliaments (ASGP) of theInter-Parliamentary Union.p. 4.Archived(PDF)from the original on 3 March 2012.Retrieved1 October2010.

- ^Chua, Amy(2002).World on Fire.Doubleday.ISBN0385503024.

- ^abRobert Kuttner,Blaming Liberalism,New York Review of Books, November 21, 2019

- ^Segrillo, Angelo (2012)."Liberalism, Marxism and Democratic Theory Revisited: Proposal of a Joint Index of Political and Economic Democracy".Brazilianpoliticalsciencereview:15.

- ^Christopher, Rice (1990).Lenin: Portrait of a Professional Revolutionary.London: Cassell. p. 121.ISBN978-0-304-31814-8.

- ^"Democracy".Left Party in Germany.Archivedfrom the original on 16 December 2017.Retrieved15 December2017.

- ^abPieke, Frank N; Hofman, Bert, eds. (2022).CPC Futures The New Era of Socialism with Chinese Characteristics.Singapore:National University of Singapore Press.pp. 60–64.doi:10.56159/eai.52060.ISBN978-981-18-5206-0.OCLC1354535847.

- ^"China criticises US democracy before Biden summit".Hindustan Times.4 December 2021.Archivedfrom the original on 7 December 2021.Retrieved11 January2023.

- ^Diamond, Larry; Plattner, Marc F.; Walker, Christopher (2016) 'Authoritarianism Goes Global: The Challenge to Democracy' Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, Summary. Available at:https://diamond-democracy.stanford.edu/Archived20 May 2023 at theWayback Machine[Last accessed 23rd January 2021]

- ^Diamond, Larry; Plattner, Marc F.; Walker, Christopher (2016) 'Authoritarianism Goes Global: The Challenge to Democracy' Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, p.23

- ^See for example, Renato Cristi,Carl Schmitt and authoritarian liberalism: strong state, free economy,Cardiff: Univ. of Wales Press, 1998; Michael A. Wilkinson, 'Authoritarian Liberalism as Authoritarian Constitutionalism', in Helena Alviar García, Günter Frankenberg,Authoritarian constitutionalism: comparative analysis and critique,Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing Limited, 2019.

- ^abKrebs, Ronald R., and Elizabeth Kier.In War's Wake : International Conflict and the Fate of Liberal Democracy.New York: Cambridge University Press, 2010.

- ^"Harvard Gazette: Freedom squelches terrorist violence".News.harvard.edu. Archived fromthe originalon 19 September 2015.Retrieved28 October2008.