Wildcat

| Wildcat | |

|---|---|

| |

| European wildcat(Felis silvestris) | |

| |

| African wildcat(Felis lybica) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Carnivora |

| Suborder: | Feliformia |

| Family: | Felidae |

| Subfamily: | Felinae |

| Genus: | Felis |

| Binomial name | |

| Felis silvestris Schreber,1777 | |

| Felis lybica Forster,1780 | |

![Distribution of the wildcat species complex[1]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/a2/Wild_Cat_Felis_silvestris_distribution_map.png/220px-Wild_Cat_Felis_silvestris_distribution_map.png)

| |

| Distribution of the wildcat species complex[1] | |

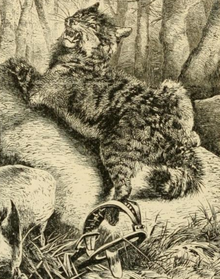

Thewildcatis aspecies complexcomprising twosmall wild catspecies:theEuropean wildcat(Felis silvestris) and theAfrican wildcat(F. lybica). The European wildcat inhabitsforestsinEurope,Anatoliaand theCaucasus,while the African wildcat inhabits semi-aridlandscapes andsteppesinAfrica,theArabian Peninsula,Central Asia,into westernIndiaand westernChina.[2] The wildcat species differ in fur pattern, tail, and size: the European wildcat has long fur and a bushy tail with a rounded tip; the smaller African wildcat is more faintly striped, has short sandy-gray fur and a tapering tail; theAsiatic wildcat(F. lybica ornata) is spotted.[3]

The wildcat and the other members of thecat familyhad acommon ancestorabout 10–15 million years ago.[4]The European wildcatevolvedduring theCromerian Stageabout 866,000 to 478,000 years ago; its direct ancestor wasFelis lunensis.[5]Thesilvestrisandlybicalineages probably diverged about 173,000 years ago.[6]

The wildcat is categorized asLeast Concernon theIUCN Red Listsince 2002, since it is widely distributed in a stable global population exceeding 20,000 mature individuals. Some local populations are threatened byintrogressivehybridisationwith thedomestic cat(F. catus), contagious disease, vehicle collisions and persecution.[1]

The association of African wildcats and humans appears to have developed along with the establishment of settlements during theNeolithic Revolution,whenrodentsin grain stores of earlyfarmersattracted wildcats. This association ultimately led to it beingtamedanddomesticated:the domestic cat is the direct descendant of the African wildcat.[7]It was one of the reveredcats in ancient Egypt.[8]The European wildcat has been the subject ofmythologyandliterature.[9][10]

Taxonomy[edit]

Felis (catus) silvestriswas thescientific nameused in 1777 byJohann von Schreberwhen hedescribedthe European wildcat based on descriptions and names proposed by earlier naturalists such asMathurin Jacques Brisson,Ulisse AldrovandiandConrad Gessner.[11] Felis lybicawas the name proposed in 1780 byGeorg Forster,who described an African wildcat fromGafsaon theBarbary Coast.[12]

In subsequent decades, several naturalists and explorers described 40 wildcatspecimenscollected in European, African and Asian range countries. In the 1940s, the taxonomistReginald Innes Pocockreviewed the collection of wildcat skins and skulls in theNatural History Museum, London,and designated sevenF. silvestrissubspeciesfrom Europe toAsia Minor,and 25F. lybicasubspecies fromAfrica,andWesttoCentral Asia.Pocock differentiated the:[13][14]

- Forest wildcatsubspecies (silvestrisgroup)

- Steppe wildcatsubspecies (ornata-caudatagroup): is distinguished from the forest wildcat by being smaller, with comparatively lighter fur colour, and longer and more sharply-pointed tails.[14]The domestic cat is thought to have derived from this group.[15][7][6]

- Bush wildcatsubspecies (ornata-lybicagroup): is distinguished from the steppe wildcat by paler fur, well-developed spot patterns and bands.[14]

In 2005, 22 subspecies were recognized by the authors ofMammal Species of the World,who allocated subspecies largely in line with Pocock's assessment.[16]

In 2017, the Cat Classification Task Force revised thetaxonomyof the Felidae, and recognized the following asvalidtaxa:[2]

| Species and subspecies | Characteristics | Image |

|---|---|---|

| European wildcat(F. silvestris) Schreber, 1777;syn.F. s. ferusErxleben,1777;obscuraDesmarest,1820;hybridaFischer,1829;feroxMartorelli, 1896;moreaTrouessart,1904;grampiaMiller,1907;tartessiaMiller, 1907;molisanaAltobello,1921;reyiLavauden,1929;jordansiSchwarz,1930;euxinaPocock, 1943;cretensisHaltenorth,1953 | This species and thenominate subspecieshas dark grey fur with distinct transverse stripes on the sides and a bushy tail with a rounded black tip.[11][13] |  |

| Caucasian wildcat(F. s. caucasica)Satunin,1905;syn.trapeziaBlackler, 1916 | This subspecies is light grey with well developed patterns on the head and back and faint transverse bands and spots on the sides. The tail has three distinct black transverse rings.[17] | |

| African wildcat(F. lybica) Forster, 1780;syn.F. l. ocreataGmelin,1791;nubiensisKerr,1792;maniculataTemminck,1824;mellandiSchwann, 1904;rubidaSchwann, 1904;ugandaeSchwann, 1904;mauritanaCabrera,1906;nandaeHeller,1913;taitaeHeller, 1913;nesteroviBirula, 1916;irakiCheesman,1921;hausaThomasandHinton,1921;griseldaThomas, 1926;brockmaniPocock, 1944;foxiPocock, 1944;pyrrhusPocock, 1944;gordoniHarrison,1968 | This species and the nominate subspecies has pale, buffish or light-greyish fur with a tinge of red on the dorsal band; the length of its pointed tail is about two-thirds of the head to body size.[18] |  |

| Southern African wildcat(F. l. cafra)Desmarest,1822;syn.F. l. xanthellaThomas, 1926; small | This subspecies does not differ significantly in colour and pattern from the nominate one. The available zoological specimens merely have slightly longer skulls than those from farther north in Africa.[14] |  |

| Asiatic wildcat(F. l. ornata)Gray,1830;syn.syriacaTristram,1867;caudataGray, 1874;maniculataYerbury and Thomas, 1895;kozloviSatunin, 1905;matschieiZukowsky,1914;griseoflavaZukowsky, 1915;longipilisZukowsky, 1915;macrothrixZukowsky, 1915;murgabensisZukowsky, 1915;schnitnikoviBirula, 1915;issikulensisOgnev,1930;tristramiPocock, 1944 | This subspecies has dark spots on light, ochreous-grey coloured fur.[14] |  |

Evolution[edit]

The wildcat is a member of the Felidae, a family that had acommon ancestorabout 10–15 million years ago.[4]Felisspeciesdivergedfrom the Felidae around 6–7 million years ago. The European wildcat diverged fromFelisabout 1.09 to 1.4 million years ago.[19]

The European wildcat's direct ancestor wasFelis lunensis,which lived in Europe in the latePlioceneandVillafranchianperiods.Fossilremains indicate that the transition fromlunensistosilvestriswas completed by theHolstein interglacialabout 340,000 to 325,000 years ago.[5]

Craniological differences between the European and African wildcats indicate that the wildcat probably migrated during theLate Pleistocenefrom Europe into the Middle East, giving rise to the steppe wildcatphenotype.[3] Phylogeneticresearch revealed that thelybicalineage probably diverged from thesilvestrislineage about 173,000 years ago.[6]

Characteristics[edit]

The wildcat has pointed ears, which are moderate in length and broad at the base.[13][14] Itswhiskersare white, number 7 to 16 on each side and reach 5–8 cm (2.0–3.1 in) in length on the muzzle. Whiskers are also present on the inner surface of the paw and measure 3–4 cm (1.2–1.6 in). Its eyes are large, with verticalpupilsand yellowish-greenirises.Theeyelashesrange from 5–6 cm (2.0–2.4 in) in length, and can number six to eight per side.[20]

The European wildcat has a greaterskullvolume than the domestic cat, a ratio known asSchauenberg's index.[21]Further, its skull is more spherical in shape than that of thejungle cat(F. chaus) andleopard cat(Prionailurus bengalensis). Itsdentitionis relatively smaller and weaker than the jungle cat's.[22]

Both wildcat species are larger than the domestic cat.[13][14]The European wildcat has relatively longer legs and a more robust build compared to the domestic cat.[23]The tail is long, and usually slightly exceeds one-half of the animal's body length. The species size varies according toBergmann's rule,with the largest specimens occurring in cool, northern areas of Europe and Asia such asMongolia,ManchuriaandSiberia.[24]Males measure 43–91 cm (17–36 in) in head to body length, 23–40 cm (9.1–15.7 in) in tail length, and normally weigh 5–8 kg (11–18 lb). Females are slightly smaller, measuring 40–77 cm (16–30 in) in body length and 18–35 cm (7.1–13.8 in) in tail length, and weighing 3–5 kg (6.6–11.0 lb).[22]

Both sexes have twothoracicand twoabdominalteats.Both sexes have pre-anal glands,consisting of moderately sizedsweatandsebaceous glandsaround theanal opening.Large-sized sebaceous andscent glandsextend along the full length of the tail on the dorsal side. Male wildcats have pre-anal pockets on the tail, activated upon reachingsexual maturity,play a significant role in reproduction andterritorial marking.[25]

Distribution and habitat[edit]

The European wildcat inhabitstemperate broadleaf and mixed forestsinEurope,Turkeyand the Caucasus. In theIberian peninsula,it occurs from sea level to 2,250 m (7,380 ft) in thePyrenees.Between the late 17th and mid 20th centuries, its European range became fragmented due to large-scale hunting and regional extirpation. It is possibly extinct in theCzech Republic,and considered regionally extinct inAustria,though vagrants fromItalyare spreading into Austria. It has never inhabitedFennoscandiaorEstonia.[1]Sicilyis the only island in theMediterranean Seawith a native wildcat population.[26]

The African wildcat lives in a wide range of habitats exceptrainforest,but throughout thesavannahsof Africa fromMauritaniaon theAtlanticcoast eastward to theHorn of Africaup to altitudes of 3,000 m (9,800 ft). Small populations live in theSaharaandNubian Deserts,Karooregion,KalahariandNamib Deserts.[27]It occurs around theArabian Peninsula's periphery to the Caspian Sea, encompassingMesopotamia,IsraelandPalestine region.In Central Asia, it ranges intoXinjiangand southernMongolia,and inSouth Asiainto theThar Desertand arid regions inIndia.[1]

Behaviour and ecology[edit]

Both wildcat species are largelynocturnalandsolitary,except during the breeding period and when females have young. The size ofhome rangesof females and males varies according to terrain, the availability of food, habitat quality and the age structure of the population. Male and female home ranges overlap, though core areas withinterritoriesare avoided by other cats. Females tend to be moresedentarythan males, as they require an exclusive hunting area when raising kittens. Wildcats usually spend the day in a hollow tree, a rock crevice or in dense thickets.[28][29] It is also reported to shelter in abandonedburrowsof other species such as ofred fox(Vulpes vulpes) and inEuropean badger(Meles meles)settsin Europe,[30]and offennec(Vulpes zerda) in Africa.[18]

When threatened, it retreats into a burrow, rather than climb trees. When taking residence in a tree hollow, it selects one low to the ground. Dens in rocks or burrows are lined with dry grasses and birdfeathers.Dens in tree hollows usually contain enough sawdust to make lining unnecessary. If the den becomes infested withfleas,the wildcat shifts to another den. During winter, when snowfall prevents the European wildcat from travelling long distances, it remains within its den until travel conditions improve.[30]

Territorial marking consists ofspraying urineon trees, vegetation and rocks, depositing faeces in conspicuous places, and leaving scent marks through glands in its paws. It also leaves visual marks by scratching trees.[31]

Hunting and prey[edit]

Sightandhearingare the wildcat's primary senses when hunting. It lies in wait for prey, then catches it by executing a few leaps, which can span three metres. When hunting near water courses, it waits on trees overhanging the water. It kills small prey by grabbing it in its claws, and piercing the neck orocciputwith its fangs. When attacking large prey, it leaps upon the animal's back, and attempts to bite the neck orcarotid.It does not persist in attacking if prey manages to escape.[32]

The European wildcat primarily preys on small mammals such asEuropean rabbit(Oryctolagus cuniculus) androdents.[33] It also preys ondormice,hares,nutria(Myocastor coypus) andbirds,especiallyducksand otherwaterfowl,galliformes,pigeonsandpasserines.[34]It can consume largebonefragments.[35]Although it killsinsectivoressuch asmolesandshrews,it rarely eats them.[34]When living close to human settlements, it preys onpoultry.[34]In the wild, it consumes up to 600 g (21 oz) of food daily.[36]

The African wildcat preys foremost onmurids,to a lesser extent also on birds, small reptiles andinvertebrates.[37]

Reproduction and development[edit]

The wildcat has twoestrusperiods, one in December–February and another in May–July.[38]Estrus lasts 5–9 days, with agestation periodlasting 60–68 days.[39]Ovulationisinduced through copulation.Spermatogenesisoccurs throughout the year. During themating season,males fight viciously,[38]and may congregate around a single female. There are records of male and female wildcats becoming temporarily monogamous. Kittens are usually born between April and May, and up to August. Litter size ranges from 1–7 kittens.[39]

Kittens are born with closed eyes and are covered in a fuzzy coat.[38]They weigh 65–163 g (2.3–5.7 oz) at birth, and kittens under 90 g (3.2 oz) usually do not survive. They are born with pink paw pads, which blacken at the age of three months, and blue eyes, which turn amber after five months.[39]Their eyes open after 9–12 days, and theirincisorserupt after 14–30 days. The kittens'milk teethare replaced by theirpermanent dentitionat the age of 160–240 days. The kittens start hunting with their mother at the age of 60 days, and start moving independently after 140–150 days.Lactationlasts 3–4 months, though the kittens eat meat as early as 1.5 months of age.Sexual maturityis attained at the age of 300 days.[38]Similarly to the domestic cat, the physical development of African wildcat kittens over the first two weeks of their lives is much faster than that of European wildcats.[40]The kittens are largely fully grown by 10 months, though skeletal growth continues for over 18–19 months. The family dissolves after roughly five months, and the kittens disperse to establish their own territories.[39]Theirmaximum life spanis 21 years, though they usually live up to 13–14 years.[38]

Generation lengthof the wildcat is about eight years.[41]

Predators and competitors[edit]

Because of its habit of living in areas with rocks and tall trees for refuge, dense thickets and abandoned burrows, wildcats have few natural predators. In Central Europe, many kittens are killed byEuropean pine marten(Martes martes), and there is at least one account of an adult wildcat being killed and eaten. Competitors include thegolden jackal(Canis aureus), red fox, marten, and other predators.[42]In the steppe regions of Europe and Asia, village dogs constitute serious enemies of wildcats, along with the much largerEurasian lynx,one of the rare habitual predators of healthy adult wildcats. In Tajikistan, thegrey wolf(Canis lupus) is the most serious competitor, having been observed to destroy cat burrows.Birds of prey,includingEurasian eagle-owl(Bubo bubo) andsaker falcon(Falco cherrug), have been recorded to kill wildcat kittens.[43]Golden eagle(Aquila chrysaetos) are known to hunt both adults and kittens.[44]Seton Gordonrecorded an instance where a wildcat fought a golden eagle, resulting in the deaths of both combatants.[45] In Africa, wildcats are occasionally killed and eaten byCentral African rock python(Python sebae)[46]andmartial eagle(Polemaetus bellicosus).[47]

Threats[edit]

Wildcat populations are foremost threatened by hybridization with the domestic cat. Mortality due to traffic accidents is a threat especially in Europe.[1]The wildcat population in Scotland has declined since the turn of the 20th century due tohabitat lossand persecution by landowners.[48]

In theformer Soviet Union,wildcats were caught accidentally in traps set for European pine marten. In modern times, they are caught in unbaited traps on pathways or at abandoned trails of red fox, European badger, European hare or pheasant. One method of catching wildcats consists of using a modified muskrat trap with a spring placed in a concealed pit. A scent trail of pheasant viscera leads the cat to the pit. Wildcat skins were of little commercial value and sometimes converted into imitationsealskin;the fur usually fetched between 50 and 60kopecks.[49] Wildcat skins were almost solely used for making cheapscarfs,muffsand coats for ladies.[50]

Conservation[edit]

Wildcat species are protected in most range countries and listed inCITES Appendix II.The European wildcat is also listed in Appendix II of theBerne Convention on the Conservation of European Wildlife and Natural Habitatsand in theEuropean Union'sHabitats and Species Directive.[1] Conservation Action Plans have been developed in Germany and Scotland.[51][52]

In culture[edit]

Domestication[edit]

An African wildcat skeletonexcavatedin a 9,500-year-old Neolithic grave in Cyprus is the earliest known indication for a close relationship between a human and a possibly tamed cat. As no cat species is native to Cyprus, this discovery indicates that Neolithic farmers may have brought cats to Cyprus from the Near East.[53]Results ofgeneticsandmorphologicalresearch corroborated that the African wildcat is the ancestor of the domestic cat. The first individuals were probably domesticated in theFertile Crescentaround the time of the introduction of agriculture.[6][7][15]Muralsand statuettes depicting cats as wellmummifiedcats indicate that it was commonly kept by ancient Egyptians since at least theTwelfth Dynasty of Egypt.[8]

In mythology[edit]

Celtic fables of theCat Sìth,a fairy creature described as resembling a large white-chested black cat, are thought to have been inspired by theKellas cat,itself thought to be a free-ranging crossbreed between a European wildcat and a domestic cat.[9]In 1693,William Salmonmentioned how body parts of the wildcat were used for medicinal purposes; its flesh for treatinggout,itsfatfor dissolvingtumoursand easing pain, its blood for curing "falling sickness",and its excrement for treatingbaldness.[10]

In heraldry[edit]

ThePictsvenerated wildcats, having probably namedCaithness(Land of the Cats) after them. According to thefoundation mythof the Catti tribe, their ancestors were attacked by wildcats upon landing in Scotland. Their ferocity impressed the Catti so much, that the wildcat became their symbol. The progenitors ofClan Sutherlanduse the wildcat as symbol on their family crest. The clan's chief bears the titleMorair Chat(Great Man of the Cats).[54] The wildcat is considered aniconof Scottish wilderness, and has been used in clan heraldry since the 13th century. TheClan ChattanAssociation (also known as the Clan of Cats) comprises 12 clans, the majority of which display the wildcat on their badges.[9]

In literature[edit]

Shakespearereferenced the wildcat three times:[10]

- The patch is kind enough; but a huge feeder

- Snail-slow in profit, and he sleeps by day

- More than thewild cat.

— The Merchant of VeniceAct 2 Scene 5 lines 47–49

- Thou must be married to no man but me;

- For I am he, am born to tame you, Kate;

- And bring you from awild catto a Kate

- Comfortable, as other household Kates.

— The Taming of the ShrewAct 2 Scene 1 lines 265–268

- Thrice thebrinded cathath mew'd.

— MacbethAct 4 Scene 1 line 1

References[edit]

- ^abcdefgYamaguchi, N.; Kitchener, A.; Driscoll, C.; Nussberger, B. (2015)."Felis silvestris".IUCN Red List of Threatened Species.2015:e.T60354712A50652361.doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2015-2.RLTS.T60354712A50652361.en.Retrieved19 February2022.

- ^abKitchener, A. C.; Breitenmoser-Würsten, C.; Eizirik, E.; Gentry, A.; Werdelin, L.; Wilting, A.; Yamaguchi, N.; Abramov, A. V.; Christiansen, P.; Driscoll, C.; Duckworth, J. W.; Johnson, W.; Luo, S.-J.; Meijaard, E.; O’Donoghue, P.; Sanderson, J.; Seymour, K.; Bruford, M.; Groves, C.; Hoffmann, M.; Nowell, K.; Timmons, Z.; Tobe, S. (2017)."A revised taxonomy of the Felidae: The final report of the Cat Classification Task Force of the IUCN Cat Specialist Group"(PDF).Cat News(Special Issue 11): 16−20.

- ^abYamaguchi, N.; Kitchener, A.; Driscoll, C. & Nussberger, B. (2004)."Craniological differentiation between European wildcats (Felis silvestris silvestris), African wildcats (F. s. lybica) and Asian wildcats (F. s. ornata): implications for their evolution and conservation "(PDF).Biological Journal of the Linnean Society.83:47–63.doi:10.1111/j.1095-8312.2004.00372.x.

- ^abJohnson, W. E.; O'Brien, S. J. (1997)."Phylogenetic Reconstruction of the Felidae Using 16S rRNA and NADH-5 Mitochondrial Genes".Journal of Molecular Evolution.44(S1): S98–S116.Bibcode:1997JMolE..44S..98J.doi:10.1007/PL00000060.PMID9071018.S2CID40185850.

- ^abKurtén, B. (1965)."On the evolution of the European Wild Cat,Felis silvestrisSchreber "(PDF).Acta Zoologica Fennica.111:3–34.

- ^abcdDriscoll, C. A.; Menotti-Raymond, M.; Roca, A. L.; Hupe, K.; Johnson, W. E.; Geffen, E.; Harley, E. H.; Delibes, M.; Pontier, D.; Kitchener, A. C.; Yamaguchi, N.; O’Brien, S. J.; Macdonald, D. W. (2007)."The Near Eastern Origin of Cat Domestication"(PDF).Science.317(5837): 519–523.Bibcode:2007Sci...317..519D.doi:10.1126/science.1139518.PMC5612713.PMID17600185.

- ^abcClutton-Brock, J. (1999)."Cats".A Natural History of Domesticated Mammals(Second ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 133–140.ISBN978-0-521-63495-3.

- ^abBaldwin, J. A. (1975). "Notes and speculations on the domestication of the cat in Egypt".Anthropos.70(3/4): 428−448.

- ^abcKilshaw 2011,pp. 2–3

- ^abcHamilton 1896,pp. 17–18

- ^abSchreber, J. C. D. (1778)."Die wilde Kaze".Die Säugthiere in Abbildungen nach der Natur mit Beschreibungen (Dritter Theil)[The mammals with illustrations and descriptions (Part 3)]. Erlangen: Expedition des Schreber'schen Säugthier- und des Esper'schen Schmetterlingswerkes. pp. 397–402.

- ^Forster, G. (1780). "LIII. Der Karakal".Herrn von Buffon's Naturgeschichte der vierfüssigen Thiere. Mit Vermehrungen, aus dem Französischen übersetzt[M. de Buffon's Natural History of Quadrupeds. With additions, translated from French]. Vol. 6. Berlin: J. Pauli. pp. 304–307.

- ^abcdPocock, R. I. (1951)."Felis silvestris,Schreber ".Catalogue of the Genus Felis.London: Trustees of the British Museum. pp. 29−50.

- ^abcdefgPocock, R. I. (1951)."Felis lybica,Forster ".Catalogue of the Genus Felis.London: Trustees of the British Museum. pp. 50−133.

- ^abHeptner & Sludskii 1992,pp. 452–455

- ^Wozencraft, W. C.(2005)."SpeciesFelis silvestris".InWilson, D. E.;Reeder, D. M. (eds.).Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference(3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 536–537.ISBN978-0-8018-8221-0.OCLC62265494.

- ^Satunin, K. A. (1905). "Die Säugetiere des Talyschgebietes und der Mughansteppe" [The Mammals of the Talysh area and the Mughan steppe].Mitteilungen des Kaukasischen Museums(2): 87–402.

- ^abRosevear, D. R. (1974)."Felis lybicaForster African Wild Cat ".The carnivores of West Africa.London: Trustees of the British Museum (Natural History). pp. 384−395.ISBN978-0565007232.

- ^Johnson, W. E.; Eizirik, E.; Pecon-Slattery, J.; Murphy, W. J.; Antunes, A.; Teeling, E.; O'Brien, S. J. (2006)."The Late Miocene Radiation of Modern Felidae: A Genetic Assessment".Science.311(5757): 73–77.Bibcode:2006Sci...311...73J.doi:10.1126/science.1122277.PMID16400146.S2CID41672825.

- ^Heptner & Sludskii 1992,pp. 402–403

- ^Schauenberg, P. (1969). "L'identification du Chat forestier d'EuropeFelis s. silvestrisSchreber, 1777 par une méthode ostéométrique ".Revue Suisse de Zoologie.76:433−441.

- ^abHeptner & Sludskii 1992,pp. 408–409

- ^Schauenberg, P. (1969). "L'identification du Chat forestier d'EuropeFelis s. silvestrisSchreber, 1777 par une méthode ostéométrique ".Revue Suisse de Zoologie.76:433−441.

- ^Heptner & Sludskii 1992,pp. 452

- ^Heptner & Sludskii 1992,pp. 405–407

- ^Mattucci, F.; Oliveira, R.; Bizzarri, L.; Vercillo, F.; Anile, S.; Ragni, B.; Lapini, L.; Sforzi, A.; Alves, P. C.; Lyons, L. A.; Randi, E. (2013)."Genetic structure of wildcat (Felis silvestris) populations in Italy ".Ecology and Evolution.3(8): 2443–2458.doi:10.1002/ece3.569.hdl:10447/600656.

- ^Nowell, K.; Jackson, P. (1996)."African WildcatFelis silvestris, lybica group(Forster, 1770) ".Wild Cats: status survey and conservation action plan.Gland, Switzerland: IUCN/SSC Cat Specialist Group. pp. 32−35. Archived fromthe originalon 2016-03-03.Retrieved2011-11-26.

- ^Guggisberg, C. A. W. (1975)."African WildcatFelis silvestris lybica(Forster, 1780) ".Wild Cats of the World.New York: Taplinger Publishing. pp.32–35.ISBN978-0-8008-8324-9.

- ^Sunquist, M.; Sunquist, F. (2002)."European wildcatFelis silvestris silvestris".Wild Cats of the World.Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. pp.85–91.ISBN0-226-77999-8.

- ^abHeptner & Sludskii 1992,pp. 433–434

- ^Harris & Yalden 2008,p. 403

- ^Heptner & Sludskii 1992,pp. 432

- ^Lozano, J.; Moleón, M.; Virgós, E. (2006)."Biogeographical patterns in the diet of the wildcat,Felis silvestrisSchreber, in Eurasia: factors affecting the trophic diversity "(PDF).Journal of Biogeography.33(6): 1076−1085.doi:10.1111/j.1365-2699.2006.01474.x.S2CID3096866.Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 2019-02-19.

- ^abcHeptner & Sludskii 1992,pp. 429–431

- ^Tomkies 2008,pp. 50

- ^Heptner & Sludskii 1992,pp. 480

- ^Herbst, M.; Mills, M. G. L. (2010). "The feeding habits of the Southern African wildcat, a facultative trophic specialist, in the southern Kalahari (Kgalagadi Transfrontier Park, South Africa/Botswana)".Journal of Zoology.280(4): 403−413.doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.2009.00679.x.hdl:2263/16378.

- ^abcdeHeptner & Sludskii 1992,pp. 434–437

- ^abcdHarris & Yalden 2008,p. 404

- ^Hemmer, H. (1990)."The origins of domestic animals".Domestication: the decline of environmental appreciation.Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 35−80.ISBN978-0521341783.

- ^Pacifici, M.; Santini, L.; Di Marco, M.; Baisero, D.; Francucci, L.; Grottolo Marasini, G.; Visconti, P.; Rondinini, C. (2013). "Generation length for mammals".Nature Conservation(5): 87–94.

- ^Heptner & Sludskii 1992,pp. 438

- ^Heptner & Sludskii 1992,pp. 491–493

- ^Hunter, Luke. Field guide to carnivores of the world. Bloomsbury Publishing, 2020.

- ^Watson, J. (2010)."Mortality".The Golden Eagle(Second ed.). London: T & AD Poyser. pp. 291−307.ISBN9781408134559.

- ^Kingdon 1988,pp. 316

- ^Hatfield, Richard Stratton. "Diet and space use of the martial eagle (Polemaetus bellicosus) in the Maasai Mara region of Kenya." (2018).

- ^Macdonald, D. W.; Yamaguchi, N.; Kitchener, A. C.; Daniels, M.; Kilshaw, K.; Driscoll, C. (2010)."Reversing cryptic extinction: the history, present and future of the Scottish Wildcat"(PDF).In Macdonald, D. W.; Loveridge, A. J. (eds.).The Biology and Conservation of Wild Felids.Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 471–492.ISBN9780199234448.[permanent dead link]

- ^Heptner & Sludskii 1992,pp. 440–441 & 496–498

- ^Bachrach, M. (1953). "Cat family − Lynx Cat and Wild Cat".Fur, a practical treatise(Third ed.). New York: Prentice-Hall Incorporated. pp. 188–189.

- ^Vogel, B.; Mölich, T.; Klar, N. (2009)."Der Wildkatzenwegeplan – Ein strategisches Instrument des Naturschutzes"[The Wildcat Infrastructure Plan – a strategic instrument of nature conservation](PDF).Naturschutz und Landschaftsplanung.41(11): 333–340. Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 2019-01-29.Retrieved2019-02-03.

- ^Scottish Wildcat Conservation Action Group (2013).Scottish Wildcat Conservation Action Plan.Edinburgh: Scottish Natural Heritage. Archived fromthe originalon 2020-07-31.Retrieved2019-02-03.

- ^Vigne, J. D.; Guilaine, J.; Debue, K.; Haye, L.; Gérard, P. (2004). "Early taming of the cat in Cyprus".Science.304(5668): 259.doi:10.1126/science.1095335.PMID15073370.S2CID28294367.

- ^Vinycomb, J. (1906)."Cat-a-Mountain − Tiger Cat or Wild Cat".Fictitious & symbolic creatures in art, with special reference to their use in British heraldry.London: Chapman and Hall Limited. pp. 205−208.

Sources[edit]

- Hamilton, E. (1896).The wild cat of Europe (Felis catus).London: R. H. Porter.

- Harris, S.; Yalden, D. W. (2008).Mammals of the British Isles(4th Revised ed.). Southampton: Mammal Society.ISBN978-0906282656.

- Heptner, V. G.; Sludskii, A. A. (1992) [1972]."Wildcat".Mlekopitajuščie Sovetskogo Soiuza. Moskva: Vysšaia Škola[Mammals of the Soviet Union, Volume II, Part 2]. Washington DC: Smithsonian Institution and the National Science Foundation. pp. 398–498.

- Kilshaw, K. (2011).Scottish Wildcats: Naturally Scottish(PDF).Perth, Scotland: Scottish Natural Heritage.ISBN9781853976834.Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 30 June 2017.Retrieved9 May2017.

- Kingdon, J. (1988).East African mammals: an atlas of evolution in Africa. Volume 3, Part 1.Chicago: University of Chicago Press.ISBN978-0226437217.

- Tomkies, M. (2008).Wildcat Haven.Dunbeath: Whittles Publishing.ISBN9781849953122.

Further reading[edit]

- Kurtén, B. (1968).Pleistocene mammals of Europe.New Brunswick and London: Aldine Transaction.ISBN9781412845144.

- Osborn, D. J.; Helmy, I. (1980)."Felis sylvestrisSchreber, 1777 ".The contemporary land mammals of Egypt (including Sinai).Chicago: Field Museum of Natural History. pp. 440−444.

External links[edit]

- "European Wildcat".IUCN/SSC Cat Specialist Group.

- "African Wildcat".IUCN/SSC Cat Specialist Group.

- "Asiatic Wildcat".IUCN/SSC Cat Specialist Group.

- "Felis silvestrisSchreber, 1777 ".UNEP Global Resource Information Database.

- "Wildcat (Felis silvestris) images ".ARKive. Archived fromthe originalon 7 April 2012.Retrieved7 April2011.

- "Felis silvestris(Schreber) ".Envis Centre of Faunal diversity. Archived fromthe originalon 2012-04-26.Retrieved2011-09-20.

- "Felis silvestris lybica,African Wildcat: 3D computed tomographic (CT) animations of male and female African wildcat skulls ".Digimorph.org.

- Scottish wildcat

- "Information and education website on the Scottish wildcat and conservation efforts".Save the Scottish Wildcat. Archived fromthe originalon 2012-09-17.Retrieved2008-02-02.

- "Conserving the Scottish wildcat in the West Highlands".Wildcat Haven. Archived fromthe originalon 2015-08-21.Retrieved2010-09-20.