William Rehnquist

William Rehnquist | |

|---|---|

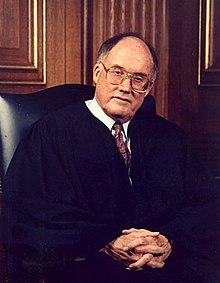

Official portrait, 1986 | |

| 16thChief Justice of the United States | |

| In office September 26, 1986 – September 3, 2005 | |

| Nominated by | Ronald Reagan |

| Preceded by | Warren E. Burger |

| Succeeded by | John Roberts |

| Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States | |

| In office January 7, 1972 – September 26, 1986 | |

| Nominated by | Richard Nixon |

| Preceded by | John Marshall Harlan II |

| Succeeded by | Antonin Scalia |

| United States Assistant Attorney Generalfor theOffice of Legal Counsel | |

| In office January 29, 1969 – December 1971 | |

| President | Richard Nixon |

| Preceded by | Frank Wozencraft |

| Succeeded by | Ralph Erickson |

| Personal details | |

| Born | William Donald Rehnquist October 1, 1924 Milwaukee,Wisconsin,U.S. |

| Died | September 3, 2005(aged 80) Arlington,Virginia,U.S. |

| Resting place | Arlington National Cemetery |

| Political party | Republican |

| Spouse |

Nan Cornell

(m.1953; died 1991) |

| Children | 3 |

| Education | Stanford University(BA,MA,LLB) Harvard University(AM) |

| Signature | |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | United States |

| Branch/service | United States Army |

| Years of service | 1943–1946 |

| Rank | |

| This article is part ofa serieson |

| Conservatism in the United States |

|---|

|

William Hubbs Rehnquist(/ˈrɛnkwɪst/REN-kwist;October 1, 1924 – September 3, 2005) was an American attorney and jurist who served as the 16thchief justiceof theU.S. Supreme Courtfrom 1986 until his death in 2005, having previously been anassociate justicefrom 1972 to 1986. Considered a staunch conservative, Rehnquist favored a conception offederalismthat emphasized theTenth Amendment's reservation of powers to the states. Under this view of federalism, the Court, for the first time since the 1930s, struck down an act of Congress as exceeding its power under theCommerce Clause.

Rehnquist grew up inMilwaukee,Wisconsin, and served in theU.S. Army Air Forcesfrom 1943 to 1946. Afterward, he studiedpolitical scienceatStanford UniversityandHarvard University,then attendedStanford Law School,where he was an editor of theStanford Law Reviewand graduated first in his class. Rehnquistclerkedfor JusticeRobert H. Jacksonduring the Supreme Court's 1952–1953 term, then entered private practice inPhoenix, Arizona.Rehnquist served as a legal adviser forRepublicanpresidential nomineeBarry Goldwaterin the1964 U.S. presidential election,and PresidentRichard Nixonappointed himU.S. Assistant Attorney Generalof theOffice of Legal Counselin 1969. In that capacity, he played a role in forcing JusticeAbe Fortasto resign for accepting $20,000 from financierLouis Wolfsonbefore Wolfson was convicted of selling unregistered shares.[1]

In 1971, Nixon nominated Rehnquist to succeed Associate JusticeJohn Marshall Harlan II,and theU.S. Senateconfirmed him that year. During his confirmation hearings, Rehnquist was criticized for allegedly opposing the Supreme Court's decision inBrown v. Board of Education(1954) and allegedly taking part invoter suppressionefforts targeting minorities as a lawyer in the early 1960s.[2]Historians debate whether he committedperjuryduring the hearings by denying his suppression efforts despite at least ten witnesses to the acts,[2]but it is known that at the very least he had defendedsegregationby private businesses in the early 1960s on the grounds offreedom of association.[2]Rehnquist quickly established himself as theBurger Court's most conservative member. In 1986, PresidentRonald Reagannominated Rehnquist to succeed retiring Chief JusticeWarren Burger,and the Senate confirmed him.

Rehnquist served as Chief Justice for nearly 19 years, making him the fourth-longest-serving chief justice and theeighth-longest-serving justiceoverall. He became an intellectual and social leader of theRehnquist Court,earning respect even from the justices who frequently opposed his opinions. As Chief Justice, Rehnquist presided over theimpeachment trialof PresidentBill Clinton.Rehnquist wrote the majority opinions inUnited States v. Lopez(1995) andUnited States v. Morrison(2000), holding in both cases that Congress had exceeded its power under the Commerce Clause. He dissented inRoe v. Wade(1973) and continued to argue thatRoehad been incorrectly decided inPlanned Parenthood v. Casey(1992). InBush v. Gore,he voted with the court's majority to end theFlorida recountin the2000 U.S. presidential election.

Early life and education[edit]

Rehnquist was born on October 1, 1924, and grew up in the Milwaukee suburb ofShorewood.His father, William Benjamin Rehnquist, was a sales manager at various times for printing equipment, paper, and medical supplies and devices; his mother, Margery (néePeck)—the daughter of a local hardware store owner who also served as an officer and director of a small insurance company—was a local civic activist, as well as a translator and homemaker.[3]His paternal grandparents immigrated fromSweden.[4][5]

Rehnquist graduated fromShorewood High Schoolin 1942.[6]He attendedKenyon College,inGambier, Ohio,for one quarter in the fall of 1942 before enlisting in theU.S. Army Air Forces,the predecessor of theU.S. Air Force.He served from 1943 to 1946, mostly in assignments in the United States. He was put into a pre-meteorologyprogram and assigned toDenison Universityuntil February 1944, when the program was shut down. He served three months atWill Rogers FieldinOklahoma City,three months inCarlsbad, New Mexico,and then went toHondo, Texas,for a few months. He was then chosen for another training program, which began atChanute Field,Illinois,and ended atFort Monmouth, New Jersey.The program was designed to teach maintenance and repair of weather instruments. In the summer of 1945, Rehnquist went overseas as a weather observer in North Africa.[7]

After leaving the military in 1946, Rehnquist attendedStanford Universitywith financial assistance from theG.I. Bill.[8]He graduated in 1948 withBachelor of ArtsandMaster of Artsdegrees inpolitical scienceand was elected toPhi Beta Kappa.He did graduate study in government atHarvard University,where he received another Master of Arts in 1950. He then returned to Stanford to attend theStanford Law School,where he was an editor on theStanford Law Review.[9]Rehnquist was strongly conservative from an early age and wrote that he "hated" liberal JusticeHugo Blackin his diary at Stanford.[10]He graduated in 1952 ranked first in his class with aBachelor of Laws.[8]Rehnquist was in the same class at Stanford Law asSandra Day O'Connor,with whom he would later serve on the Supreme Court. They briefly dated during law school,[11]and Rehnquist proposed marriage to her. O'Connor declined as she was by then dating her future husband (this was not publicly known until 2018).[12]Rehnquist married Nan Cornell in 1953.

Law clerk at the Supreme Court[edit]

After law school, Rehnquist served as alaw clerkfor U.S. Supreme Court justiceRobert H. Jacksonfrom 1952 to 1953.[13]While clerking for Jackson, he wrote a memorandum arguing against federal court-orderedschool desegregationwhile the Court was considering the landmark caseBrown v. Board of Education,which was decided in 1954. Rehnquist's 1952 memo, "A Random Thought on the Segregation Cases", defended theseparate-but-equaldoctrine. In the memo, Rehnquist wrote:

To the argument that a majority may not deprive a minority of its constitutional right, the answer must be made that while this is sound in theory, in the long run it is the majority who will determine what the constitutional rights of the minority are [...] I realize that it is an unpopular and unhumanitarian position, for which I have been excoriated by "liberal" colleagues, but I thinkPlessy v. Fergusonwas right and should be reaffirmed.[14]

In both his 1971United States Senateconfirmation hearingforAssociate Justiceand his 1986 hearing forChief Justice,Rehnquist testified that the memorandum reflected Jackson's views rather than his own. Rehnquist said, "I believe that the memorandum was prepared by me as a statement of Justice Jackson's tentative views for his own use."[15]Jackson's longtime secretary and confidante Elsie Douglas said during Rehnquist's 1986 hearings that his allegation was "a smear of a great man, for whom I served as secretary for many years. Justice Jackson did not ask law clerks to express his views. He expressed his own and they expressed theirs. That is what happened in this instance."[16]But JusticesDouglas's andFrankfurter's papers indicate that Jackson voted forBrownin 1954 only after changing his mind.[17]

At his 1986 hearing for chief justice, Rehnquist tried to further distance himself from the 1952 memo, saying, "The bald statement that Plessy was right and should be reaffirmed was not an accurate reflection of my own views at the time."[18]But he acknowledged defendingPlessyin arguments with fellow law clerks.[19]

Several commentators have concluded that the memo reflected Rehnquist's own views, not Jackson's.[20][21]A biography of Jackson corroborates this, stating that Jackson instructed his clerks to express their views, not his.[22]Further corroboration is found in a 2012Boston College Law Reviewarticle that analyzes a 1955 letter to Frankfurter that criticized Jackson.[23]

In any event, while serving on the Supreme Court, Rehnquist made no effort to reverse or undermineBrownand often relied on it as precedent.[24][25]In 1985, he said there was a "perfectly reasonable" argument againstBrownand in favor ofPlessy,even though he now sawBrownas correct.[22]

In a memorandum to Jackson aboutTerry v. Adams,[26]which involved the right of blacks to vote in Texas primaries where a non-binding white-only pre-election was being used to preselect the winner before the actual primary, Rehnquist wrote:

The Constitution does not prevent the majority from banding together, nor does it attain success in the effort. It is about time the Court faced the fact that the white people of the south do not like the colored people. The Constitution restrains them from effecting this dislike through state action, but it most assuredly did not appoint the Court as a sociological watchdog to rear up every time private discrimination raises its admittedly ugly head.[6]

In another memorandum to Jackson about the same case, Rehnquist wrote:

several of the [Yale law professor Fred] Rodell school of thought among the clerks began screaming as soon as they saw this that 'Now we can show those damn southerners, etc.' [...] I take a dim view of this pathological search for discrimination [...] and as a result I now have something of a mental block against the case.[27]

Nevertheless, Rehnquist recommended to Jackson that the Supreme Court should agree to hearTerry.

Private practice[edit]

After his Supreme Court clerkship, Rehnquist entered private practice inPhoenix,Arizona,where he worked from 1953 to 1969. He began his legal work in the firm ofDenison Kitchel,subsequently serving as the national manager ofBarry M. Goldwater's1964presidential campaign. Prominent clients includedJim Hensley,John McCain's future father-in-law.[28]During these years, Rehnquist was active in theRepublican Partyand served as a legal advisor under Kitchel to Goldwater's campaign.[29]He collaborated withHarry Jaffaon Goldwater's speeches.[30]

During both his 1971 hearing for associate justice and his 1986 hearing for chief justice, several people came forward to allege that Rehnquist had participated inOperation Eagle Eye,a Republican Partyvoter suppressionoperation in the early 1960s in Arizona to challenge minority voters.[31]Rehnquist denied the charges, and Vincent Maggiore, then chairman of the Phoenix-area Democratic Party, said he had never heard any negative reports about Rehnquist'sElection Dayactivities. "All of these things", Maggiore said, "would have come through me."[32]

Justice Department[edit]

WhenRichard Nixonwas electedpresidentin1968,Rehnquist returned to work in Washington. He served asAssistant Attorney Generalof theOffice of Legal Counselfrom 1969 to 1971.[33]In this role, he served as the chief lawyer toAttorney GeneralJohn Mitchell.Nixon mistakenly called him "Renchburg" in several of the tapes ofOval Officeconversations revealed during theWatergateinvestigations.[34]

Rehnquist played a role in the investigation of JusticeAbe Fortasfor accepting $20,000 fromLouis Wolfson,a financier under investigation by theSecurities and Exchange Commission.[35]Although other justices had made similar arrangements, Nixon saw the Wolfson payment as a political opportunity to cement a conservative majority on the Supreme Court.[35]Nixon wanted the Justice Department to investigate Fortas but was unsure if this was legal, as there was no precedent for such an activity.[36]Rehnquist sent Attorney GeneralJohn N. Mitchella memo arguing that an investigation would not violate theseparation of powers.[36]Rehnquist did not handle the direct investigation, but was told by Mitchell to "assume the most damaging set of inferences about the case were true" and "determine what action the Justice Department could take."[37]The worst inference Rehnquist could draw was that Fortas had somehow intervened in the prosecution of Wolfson, which, according to former White House Counsel John W. Dean, was untrue.[37]Based on this false accusation, Rehnquist argued that the Justice Department could investigate Fortas.[37]After being investigated by Mitchell, who threatened to also investigate his wife, Fortas resigned.[38]

Because he was well-placed in theJustice Department,many suspected Rehnquist could have been the source known asDeep Throatduring theWatergate scandal.[39]OnceBob Woodwardrevealed on May 31, 2005, thatW. Mark FeltwasDeep Throat,this speculation ended.

Associate Justice[edit]

Nomination and confirmation as associate justice[edit]

On October 21, 1971, President Nixon nominated Rehnquist as an associate justice of the Supreme Court, to succeedJohn Marshall Harlan II.[40]Henry Kissingerinitially proposed Rehnquist for the position to presidential advisorH.R. Haldemanand asked, "Rehnquist is pretty far right, isn't he?" Haldeman responded, "Oh, Christ! He's way to the right of Buchanan",[41]referring to then-presidential advisorPatrick Buchanan.

Rehnquist's confirmation hearings before theSenate Judiciary Committeetook place in early November 1971.[42][43]In addition to answering questions about school desegregation and racial discrimination in voting, Rehnquist was asked about his views on the extent of presidential power, theVietnam War,theanti-war movementand law enforcementsurveillance methods.[44]On November 23, 1971, the committee voted 12–4 to send the nomination to the full Senate with a favorable recommendation.[42][43]

On December 10, 1971, the Senate first voted 52–42 against acloturemotion that would have allowed the Senate to end debate on Rehnquist's nomination and vote on whether to confirm him.[42][45]The Senate then voted 22–70 to reject a motion to postpone consideration of his confirmation until July 18, 1972.[42]Later that day, the Senate voted 68–26 to confirm Rehnquist,[42][46]and he took thejudicial oath of officeon January 7, 1972.[47]

There were two Supreme Court vacancies in the fall of 1971. The other was filled byLewis F. Powell Jr.,who took office on the same day as Rehnquist to replaceHugo Black.[46][47]

Tenure as associate justice[edit]

On the Court, Rehnquist promptly established himself as Nixon's most conservative appointee, taking a narrow view of theFourteenth Amendmentand a broad view of state power in domestic policy. He almost always voted "with the prosecution in criminal cases, with business in antitrust cases, with employers in labor cases, and with the government in speech cases."[48]Rehnquist was often a lone dissenter in cases early on, but his views later often became the Court's majority view.[8]

Federalism[edit]

For years, Rehnquist was determined to keep cases involving individual rights in state courts out of federal reach.[48][49]InNational League of Cities v. Usery(1977), his majority opinion invalidated a federal law extendingminimum wageand maximum hours provisions to state and local government employees.[50]Rehnquist wrote, "this exercise of congressional authority does not comport with the federal system of government embodied in the Constitution."[50]

Equal protection, civil rights, and abortion[edit]

Rehnquist rejected a broad view of the Fourteenth Amendment. In 1952, while clerking for Jackson, Rehnquist wrote a memorandum concluding that "Plessy v. Fergusonwas right and should be re-affirmed. If the Fourteenth Amendment did not enact Spencer'sSocial Statics,it just as surely did not enact Myrddahl's American Dilemma "(An American Dilemma), by which he meant that the Court should not "read its own sociological views into the Constitution."[51]Rehnquist believed the Fourteenth Amendment was meant only as a solution to the problems of slavery, and was not to be applied to abortion rights or prisoner's rights.[48][52]He believed the Court "had no business reflecting society's changing and expanding values" and that this was Congress's domain.[48]Rehnquist tried to weave his view of the Amendment into his opinion forFitzpatrick v. Bitzer,but the other justices rejected it.[52]He later extended what he said he saw as the Amendment's scope, writing inTrimble v. Gordon,"except in the area of the law in which the Framers obviously meant it to apply—classifications based on race or on national origin".[53]During the Burger Court's deliberations overRoe v. Wade,Rehnquist promoted his view that courts' jurisdiction does not apply toabortion.[54]

Rehnquist voted against the expansion ofschool desegregationplans and the establishment of legalized abortions, dissenting inRoe v. Wade.He expressed his views about theEqual Protection Clausein cases likeTrimble v. Gordon:[53]

Unfortunately, more than a century of decisions under this Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment have produced... a syndrome wherein this Court seems to regard the Equal Protection Clause as a cat-o'-nine-tails to be kept in the judicial closet as a threat to legislatures which may, in the view of the judiciary, get out of hand and pass "arbitrary", "illogical", or "unreasonable" laws. Except in the area of the law in which the Framers obviously meant it to apply—classifications based on race or on national origin, the first cousin of race—the Court's decisions can fairly be described as an endless tinkering with legislative judgments, a series of conclusions unsupported by any central guiding principle.

Other issues[edit]

Rehnquist consistently defended state-sanctionedprayer in public schools.[22]He held a restrictive view of criminals' and prisoners' rights and believedcapital punishmentto be constitutional.[55]He supported the view that the Fourth Amendment permitted a warrantless search incident to a valid arrest.[56]

InNixon v. Administrator of General Services(1977), Rehnquist dissented from a decision upholding the constitutionality of an act that gave a federal agency administrator certain authority over former President Nixon's presidential papers and tape recordings.[57]He dissented solely on the ground that the law was "a clear violation of the constitutional principle of separation of powers".[50][57]

During oral argument inDuren v. Missouri(1978), the Court faced a challenge to laws and practices that made jury duty voluntary for women in that state. At the end ofRuth Bader Ginsburg's oral presentation, Rehnquist asked her, "You will not settle for puttingSusan B. Anthonyon the new dollar, then? "[58]

Rehnquist wrote the majority opinion inDiamond v. Diehr,450U.S.175(1981), which began a gradual trend toward overturning the ban on software patents in the United States first established inParker v. Flook,437U.S.584(1978). InSony Corp. of America v. Universal City Studios, Inc.,pertaining tovideo cassette recorderssuch as the Betamax system,John Paul Stevenswrote an opinion providing a broadfair usedoctrine while Rehnquist joined the dissent supporting stronger copyrights. InEldred v. Ashcroft,537U.S.186(2003), Rehnquist was in the majority favoring the copyright holders, with Stevens andStephen Breyerdissenting in favor of a narrower construction of copyright law.

View of the rational basis test[edit]

Harvard Universitylaw professor David Shapiro wrote that as an associate justice, Rehnquist disliked even minimal inquiries into legislative objectives except in the areas of race, national origin, and infringement of specific constitutional guarantees.[59]For Rehnquist, therational basis testwas not a standard for weighing the interests of the government against the individual but a label to describe a preordained result.[59]In 1978, Shapiro pointed out that Rehnquist had avoided joining rational basis determinations for years, except in one case,Weinberger v. Wiesenfeld.[59]InTrimble v. Gordon,Rehnquist eschewed the majority's approach to equal protection, writing in dissent that the state's distinction should be sustained because it was not "mindless and patently irrational".[59](The Court struck down an Illinois law allowing illegitimate children to inherit by intestate succession only from their mothers.) Shapiro wrote that Rehnquist seemed content to find a sufficient relationship between a challenged classification and perceived governmental interests "no matter how tenuous or speculative that relationship might be".[59][60]

A practical result of Rehnquist's view of rational basis can be seen inCleveland Board of Education v. LaFleur,wherein the Court's majority struck down a school board rule that required every pregnant teacher to take unpaid maternity leave beginning five months before the expected birth of her child.[60]Lewis Powell had written an opinion resting on the ground that the school board rule was too inclusive to survive equal protection analysis.[60]In dissent, Rehnquist attacked Powell's opinion, saying:

If legislative bodies are to be permitted to draw a line anywhere short of the delivery room, I can find no judicial standard of measurement which says the ones drawn here were invalid.[60]

Shapiro writes that Rehnquist's opinion implied:

That there is no constitutionally significant difference between a classification that encompasses virtually no one outside the scope of its purpose and a classification so overinclusive that the vast majority of those falling within are beyond its intended scope.[60]

Rehnquist's dissent inUnited States Department of Agriculture v. Murryilluminates his view that a classification should pass muster under the rational basis test so long as that classification is not entirely counterproductive with respect to the purposes of the legislation in which it is contained.[61]Shapiro alleges that Rehnquist's stance "makes rational basis a virtual nullity".[60]

Relations on the Court[edit]

Rehnquist quickly became well-liked and developed friendly personal relations with his colleagues, even with ideological opposites.William J. Brennan Jr."startled one acquaintance by informing him that 'Bill Rehnquist is my best friend up here.'"[62]Rehnquist andWilliam O. Douglasbonded over a shared iconoclasm and love of the West.[63]The Brethrenclaims that the Court's "liberals found it hard not to like the good-natured, thoughtful Rehnquist", despite finding his legal philosophy "extreme",[64]and thatPotter Stewartregarded Rehnquist as "excellent" and "a" team player, a part of the group in the center of the court, even though he usually ended up in the conservative bloc ".[65]

Since Rehnquist's first years on the Supreme Court, other justices criticized what they saw as his "willingness to cut corners to reach a conservative result", "gloss[ing] over inconsistencies of logic or fact" or distinguishing indistinct cases to reach their destination.[66][67]InJefferson v. Hackney,for example, Douglas andThurgood Marshallcharged that Rehnquist's opinion "misrepresented the legislative history"[68]of a federal welfare program.[69]Rehnquist did not correct whatThe Brethrencharacterizes as an "outright misstatement,... [and thus] publish[ed] an opinion that twisted the facts".[68]His "misuse" of precedents in another case "shocked" Stevens.[70]For his part, Rehnquist was often "contemptuous of Brennan's opinions", seeing them as "bending the facts or law to suit his purposes".[71]Rehnquist had a tense relationship with Marshall, who sometimes accused him of bigotry.[72]

Rehnquist usually voted with Chief JusticeWarren Burger,[73]and, recognizing "the importance of his relationship with Burger", often went along to get along, joining Burger's majority opinions even when he disagreed with them, and, in important cases, "tr[ying] to straighten him out".[71]Even so, being reluctant to compromise, Rehnquist was the most frequent sole dissenter during theBurger Court,garnering the nickname "the Lone Ranger".[22]

Chief Justice[edit]

Nomination and confirmation as chief justice[edit]

When Burger retired in 1986, PresidentRonald Reagannominated Rehnquist for chief justice. Although Rehnquist was far more conservative than Burger,[74]"his colleagues were unanimously pleased and supportive", even his "ideological opposites".[62]The nomination "was met with 'genuine enthusiasm on the part of not only his colleagues on the Court but others who served the Court in a staff capacity and some of the relatively lowly paid individuals at the Court. There was almost a unanimous feeling of joy.'"[62]Thurgood Marshall later called him "a great chief justice".[25]

The nomination was submitted to the Senate Judiciary Committee on July 20, 1986. This was the first confirmation hearing on a chief justice nominee to be opened to gavel-to-gavel television coverage.[75]During the hearing, SenatorTed Kennedychallenged Rehnquist on his unwitting ownership of property that had arestrictive covenantagainst sale to Jews[76](such covenants were held to be unenforceable under the 1948 Supreme Court caseShelley v. Kraemer). Along with senatorsJoe BidenandHoward Metzenbaum,Kennedy called Rehnquist "insensitive to minorities and women's rights while on the court."[77]Rehnquist also drew criticism for his membership in the Washington, D.C.Alfalfa Club,which at the time did not allow women to join.[78]On August 14, the Judiciary Committee voted 13–5 to report the nomination to the Senate with a favorable recommendation.[42]

Despite various Democrats' efforts to defeat the nomination, the Senate confirmed Rehnquist on September 17. After cloture was invoked in a 68–31 vote,[42]Rehnquist was confirmed in a 65–33 vote (49 Republicans and 16 Democrats voted in favor; 31 Democrats and two Republicans voted against).[77]He took office on September 26, becoming the first person sinceHarlan F. Stoneto serve as both an associate justice and chief justice. Rehnquist's associate justice successor,Antonin Scalia,was sworn into office that same day.[75]

Rehnquist had no prior experience as a judge upon his appointment to the Court. His only experience in presiding over a case at the trial level was in 1984, when Judge D. Dortch Warriner invited him to preside over a civil case,Julian D. Heislup, Sr. and Linda L. Dixon, Appellees, v. Town of Colonial Beach, Virginia, et al.Exercising the authority of a Supreme Court justice to preside over lower court proceedings, he oversaw the jury trial involving allegations that police department employees' civil rights were violated when they testified in a matter involving alleged police brutality against a teenage boy.[79]Rehnquist ruled for the plaintiffs in a number of motions, allowing the case to go to the jury. When the jury found for the plaintiffs and awarded damages, the defendants appealed. The appeal was argued before the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals on June 4, 1986–16 days before Rehnquist was nominated as chief justice. Forty-three days after Rehnquist was sworn in as chief justice, the Fourth Circuit reversed the judgment, overruling Rehnquist, and concluding that there was insufficient evidence to have sent the matter to the jury.[80]

Tenure as chief justice[edit]

Presidential oaths administered[edit]

In his capacity as chief justice, Rehnquist administered theOath of Officeto the following presidents of the United States:

- George H. W. Bushin 1989

- Bill Clintonin 1993 and 1997

- George W. Bushin 2001 and 2005

Leadership of the Court[edit]

Rehnquist tightened up the justices' conferences, keeping justices from going too long or off track and not allowing any justice to speak twice until each had spoken once, and gained a reputation for scrupulous fairness in assigning opinions: Rehnquist assigned no justice (including himself) two opinions before everyone had been assigned one, and made no attempts to interfere with assignments for cases in which he was in the minority. Most significantly, he successfully lobbied Congress in 1988 to give the Court control of its own docket, cutting back on mandatory appeals and certiorari grants in general.[81]

Rehnquist added four yellow stripes to the sleeves of his robe in 1995. A lifelong fan ofGilbert and Sullivanoperas, he liked theLord Chancellor's costume in a community theater production ofIolanthe,and thereafter appeared in court with the same striped sleeves.[82]His successor, Chief JusticeJohn Roberts,chose not to continue the practice.[83]

Federalism doctrine[edit]

Scholars expected Rehnquist to push the Supreme Court in a more conservative direction during his tenure. Many commentators expected to see the federal government's power limited and state governments' power increased.[84]However, legal reporter Jan Crawford has said that some of Rehnquist's victories toward the federalist goal of scaling back congressional power over the states had little practical impact.[85]

Rehnquist voted with the majority inCity of Boerne v. Flores(1997), and referred to that decision as precedent for requiring Congress to defer to the Court when interpreting the Fourteenth Amendment (including the Equal Protection Clause) in a number of cases.Boerneheld that any statute that Congress enacted to enforce the Fourteenth Amendment (including the Equal Protection Clause) had to show "a congruence and proportionality between the injury to be prevented or remedied and the means adopted to that end". The Rehnquist Court's congruence and proportionality theory replaced the "ratchet" theory that had arguably been advanced inKatzenbach v. Morgan(1966).[86]According to the ratchet theory, Congress could "ratchet up" civil rights beyond what the Court had recognized, but Congress could not "ratchet down" judicially recognized rights. According to the majority opinion of JusticeAnthony Kennedy,which Rehnquist joined inBoerne:

There is language in our opinion inKatzenbach v. Morgan,384 U.S. 641 (1966), which could be interpreted as acknowledging a power in Congress to enact legislation that expands the rights contained in §1 of the Fourteenth Amendment. This is not a necessary interpretation, however, or even the best one.... If Congress could define its own powers by altering the Fourteenth Amendment's meaning, no longer would the Constitution be "superior paramount law, unchangeable by ordinary means".

The Rehnquist Court's congruence and proportionality standard made it easier to revive older precedents preventing Congress from going too far[87]in enforcing equal protection of the laws.[88]

One of the Rehnquist Court's major developments involved reinforcing and extending the doctrine ofsovereign immunity,[89]which limits the ability of Congress to subject non-consenting states to lawsuits by individual citizens seeking money damages.

In bothKimel v. Florida Board of Regents(2000) andBoard of Trustees of the University of Alabama v. Garrett(2001), the Court held that Congress had exceeded its power to enforce the Equal Protection Clause. In both cases, Rehnquist was in the majority that held discrimination by states based upon age or disability (as opposed to race or gender) need satisfy onlyrational basis reviewas opposed tostrict scrutiny.

Though theEleventh Amendmentby its terms applies only to suits against a state by citizens of another state, the Rehnquist Court often extended this principle to suits by citizens against their own states. One such case wasAlden v. Maine(1999), in which the Court held that the authority to subject states to private suits does not follow from any of the express enumerated powers in Article I of the Constitution, and therefore looked to theNecessary and Proper Clauseto see whether it authorized Congress to subject the states to lawsuits by the state's own citizens. Rehnquist agreed with Kennedy's statement that such lawsuits were not "necessary and proper":

Nor can we conclude that the specific Article I powers delegated to Congress necessarily include, by virtue of the Necessary and Proper Clause or otherwise, the incidental authority to subject the States to private suits as a means of achieving objectives otherwise within the scope of the enumerated powers.

Rehnquist also led the Court toward a more limited view of Congressional power under theCommerce Clause.For example, he wrote for a 5-to-4 majority inUnited States v. Lopez,514U.S.549(1995), striking down a federal law as exceeding congressional power under the Clause.

Lopezwas followed byUnited States v. Morrison,529U.S.598(2000), in which Rehnquist wrote the Court's opinion striking down the civil damages portion of theViolence Against Women Actof 1994 as regulating conduct that has no significant direct effect on interstate commerce. Rehnquist's majority opinion inMorrisonalso rejected anEqual Protectionargument on the Act's behalf. All four dissenters disagreed with the Court's interpretation of the Commerce Clause, and two dissenters, Stevens and Breyer, also took issue with the Court's Equal Protection analysis.David Souterasserted that the Court was improperly seeking to convert the judiciary into a "shield against the commerce power".

Rehnquist's majority opinion inMorrisoncited precedents limiting the Equal Protection Clause's scope, such asUnited States v. Cruikshank(1876), which held that the Fourteenth Amendment applied only to state actions, not private acts of violence. Breyer, joined by Stevens, agreed with the majority that it "is certainly so" that Congress may not "use the Fourteenth Amendment as a source of power to remedy the conduct of private persons", but took issue with another aspect of theMorrisonCourt's Equal Protection analysis, arguing that cases that the majority had cited (includingUnited States v. Harrisand theCivil Rights Cases,regarding lynching and segregation, respectively) did not consider "this kind of claim" in which state actors "failed to provide adequate (or any) state remedies". In response, theMorrisonmajority asserted that the Violence Against Women Act was "directed not at any State or state actor, but at individuals who have committed criminal acts motivated by gender bias".

The federalist trendLopezandMorrisonset was seemingly halted byGonzales v. Raich(2005), in which the Court broadly interpreted the Commerce Clause to allow Congress to prohibit the intrastate cultivation ofmedicinalcannabis.Rehnquist, O'Connor and JusticeClarence Thomasdissented inRaich.

Rehnquist authored the majority opinion inSouth Dakota v. Dole(1987), upholding Congress's reduction of funds to states not complying with the national 21-year-old drinking age. Rehnquist's broad reading of Congress's spending power was also seen as a major limitation on the Rehnquist Court's push to redistribute power from the federal government to the states.

According to law professorErwin Chemerinsky,[90]Rehnquist presided over a "federalist revolution" as chief justice, butCato InstitutescholarRoger Pilonhas said that "[t]he Rehnquist court has revived the doctrine of federalism, albeit only at the edges and in very easy cases."[91]

Stare decisis[edit]

Some commentators expected the Rehnquist Court to overrule several controversial decisions broadly interpreting the Bill of Rights.[22]But the Rehnquist Court expressly declined to overruleMiranda v. ArizonainDickerson v. United States.Rehnquist believed that federal judges should not impose their personal views on the law or stray beyond the framers' intent by reading broad meaning into the Constitution; he saw himself as an "apostle of judicial restraint".[22]Columbia Law SchoolProfessorVincent Blasisaid of Rehnquist in 1986 that "[n]obody since the 1930s has been so niggardly in interpreting the Bill of Rights, so blatant in simply ignoring years and years of precedent."[22]In the same article, Rehnquist was quoted as retorting that "such attacks come from liberal academics and that 'on occasion, they write somewhat disingenuously about me'."

Rehnquist disagreed withRoe v. Wade.In 1992,Roesurvived by a 5–4 vote inPlanned Parenthood v. Casey,which relied heavily on the doctrine ofstare decisis.Dissenting inCasey,Rehnquist criticized the Court's "newly minted variation onstare decisis",and asserted" thatRoewas wrongly decided, and that it can and should be overruled consistently with our traditional approach tostare decisisin constitutional cases ".[92]

The Court decided another abortion case, this time dealing withpartial birth abortion,inStenberg v. Carhart(2000). Again, the vote was 5–4, and again Rehnquist dissented, urging thatstare decisisnot be the sole consideration: "I did not join the joint opinion inPlanned Parenthood of Southeastern Pa. v. Casey,505 U. S. 833 (1992), and continue to believe that case is wrongly decided. "

LGBT rights[edit]

In a 1977 dissent in the case of Ratchford v. Gay Lib, Rehnquist gave weight to thepseudoscientificnotion that homosexuality is contagious.[93][94]

Rehnquist joined the majority opinion inBowers v. Hardwickupholding the outlawing of gay sex acts as constitutional, and did not join Chief Justice Burger's concurrence.[95]

InRomer v. Evans(1996), Colorado adopted an amendment to the state constitution that would have prevented any municipality within the state from taking any legislative, executive, or judicial action to protect citizens from discrimination on the basis of theirsexual orientation.Rehnquist joined Scalia's dissent, which argued that since the Constitution says nothing about this subject, "it is left to be resolved by normal democratic means". The dissent argued as follows (some punctuation omitted):

General laws and policies that prohibit arbitrary discrimination would continue to prohibit discrimination on the basis of homosexual conduct as well. This... lays to rest such horribles, raised in the course of oral argument, as the prospect that assaults upon homosexuals could not be prosecuted. The amendment prohibits special treatment of homosexuals, and nothing more. It would not affect, for example, a requirement of state law that pensions be paid to all retiring state employees with a certain length of service; homosexual employees, as well as others, would be entitled to that benefit.

The dissent mentioned the Court's then-existing precedent inBowers v. Hardwick(1986), that "the Constitution does not prohibit what virtually all States had done from the founding of the Republic until very recent years—making homosexual conduct a crime." By analogy, theRomerdissent reasoned that:

If it is rational to criminalize the conduct, surely it is rational to deny special favor and protection to those with a self avowed tendency or desire to engage in the conduct.

The dissent listed murder,polygamy,and cruelty to animals as behaviors that the Constitution allows states to be very hostile toward, and said, "the degree of hostility reflected by Amendment 2 is the smallest conceivable." It added:

I would not myself indulge in... official praise for heterosexual monogamy, because I think it no business of the courts (as opposed to the political branches) to take sides in this culture war. But the Court today has done so, not only by inventing a novel and extravagant constitutional doctrine to take the victory away from traditional forces, but even by verbally disparaging as bigotry adherence to traditional attitudes.

InLawrence v. Texas(2003), the Supreme Court overruledBowers.Rehnquist again dissented, along with Scalia and Thomas. The Court's result inRomerhad described the struck-down statute as "a status-based enactment divorced from any factual context from which we could discern a relationship to legitimate state interests".[96]The sentiment behind that statute had led the Court to evaluate it with a "more searching" form of review.[97]Similarly, inLawrence,"moral disapproval" was found to be an unconstitutional basis for condemning a group of people.[97]The Court protected homosexual behavior in the name of liberty and autonomy.[97]

Rehnquist sometimes reached results favorable to homosexuals−for example, voting to allow a gayCIAemployee to sue on the basis of constitutional law for improper personnel practices (although barring suit on the basis of administrative law in deference to a claim of national security reasons),[98]to allow same-sexsexual harassmentclaims to be adjudicated,[99]and to allow theUniversity of Wisconsin–Madisonto require students to pay a mandatory fee that subsidized gay groups along with other student organizations.[100]

Because of his votes in gay rights cases,ACT UPincluded Rehnquist alongsideRonald Reagan,George H. W. Bush,Jerry Falwell,andJesse Helmsin a series of posters denouncing what it regarded as leading figures in the anti-gay movement in America.[101]

Civil Rights Act[edit]

InAlexander v. Sandoval(2001), which involved the issue of whether a citizen could sue a state for not providingdriver's licenseexams in languages other than English, Rehnquist voted with the majority in denying a private right to sue for discrimination based on race or national origin involving disparate impact under Title VI of theCivil Rights Act of 1964.SandovalcitedCannon v. University of Chicago(1979) as precedent. The Court ruled 5–4 that various facts (regarding disparate impact) mentioned in a footnote ofCannonwere not part of the holding ofCannon.The majority also viewed it as significant that §602 of Title VI did not repeat the rights-creating language (race, color, or national origin) in §601.

Religion clauses[edit]

In 1992, Rehnquist joined a dissenting opinion inLee v. Weismanarguing that the Free Exercise Clause of the First Amendment only forbids government from preferring one particular religion over another.[102]Souter wrote a separate concurrence specifically addressed to Rehnquist on this issue.[102]

Rehnquist also led the way in allowing greater state assistance to religious schools, writing another 5-to-4 majority opinion inZelman v. Simmons-Harristhat approved aschool voucherprogram that aided church schools along with other private schools.

InVan Orden v. Perry(2005), Rehnquist wrote theplurality opinionupholding the constitutionality of a display of theTen Commandmentsat the Texas state capitol inAustin.He wrote:

Our cases,Januslike, point in two directions in applying theEstablishment Clause.One face looks toward the strong role played by religion and religious traditions throughout our Nation's history.... The other face looks toward the principle that governmental intervention in religious matters can itself endanger religious freedom.

This opinion was joined by Scalia, Thomas, Breyer, and Kennedy.

First Amendment[edit]

University of Chicago Law SchoolProfessorGeoffrey Stonehas written that Rehnquist was by an impressive margin the justice least likely to invalidate a law as violating "the freedom of speech, or of the press".[103]Burger was 1.8 times more likely to vote in favor of the First Amendment; Scalia, 1.6 times; Thomas, 1.5 times.[103]Excluding unanimous Court decisions, Rehnquist voted to reject First Amendment claims 92% of the time.[103]In issues involving freedom of the press, he rejected First Amendment claims 100% of the time.[103]Stone wrote:

There were only three areas in which Rehnquist showed any interest in enforcing the constitutional guarantee of free expression: in cases involving advertising, religious expression, and campaign finance regulation.[103]

But, as he did inBigelow v. Commonwealth of Virginia,Rehnquist voted against freedom of advertising if an advertisement involvedbirth controlor abortion.

Fourteenth Amendment[edit]

Rehnquist wrote a concurrence agreeing to strike down the male-only admissions policy of theVirginia Military Instituteas violating the Equal Protection Clause,[104][105]but declined to join the majority opinion's basis for using theFourteenth Amendment,writing:

HadVirginiamade a genuine effort to devote comparable public resources to a facility for women, and followed through on such a plan, it might well have avoided an equal protection violation.[105]

This rationale supported facilities separated on the basis of gender:

It is not the 'exclusion of women' that violates the Equal Protection Clause, but the maintenance of an all-men school without providing any—much less a comparable—institution for women.... It would be a sufficient remedy, I think, if the two institutions offered the same quality of education and were of the same overall caliber.[105]

Rehnquist remained skeptical about the Court's Equal Protection Clause jurisprudence; some of his opinions most favorable to equality resulted from statutory rather than constitutional interpretation. For example, inMeritor Savings Bank v. Vinson(1986), Rehnquist established a hostile-environment sexual harassment cause of action under Title VII of theCivil Rights Act of 1964,including protection against psychological aspects of harassment in the workplace.

Bush v. Gore[edit]

In 2000, Rehnquist wrote a concurring opinion inBush v. Gore,the case that ended thepresidential election controversy in Florida,agreeing with four other justices that theEqual Protection Clausebarred the "standardless" manual recount ordered by theFlorida Supreme Court.

Presiding officer of the Clinton impeachment trial[edit]

In 1999, Rehnquist became the second chief justice (afterSalmon P. Chase) to preside over a presidentialimpeachment trial,during the proceedings against PresidentBill Clinton.He was a generally passive presiding officer, once commenting on his stint as presiding officer, "I did nothing in particular, and I did it very well."[106]In 1992, Rehnquist wroteGrand Inquests,a book analyzing boththe impeachmentofAndrew Johnsonandthe impeachmentofSamuel Chase.[107]

Legacy[edit]

Jeffery Rosen has argued that Rehnquist's "tactical flexibility was more effective than the rigid purity of Scalia and Thomas."[108]Rosen writes:

In truth, Rehnquist carefully staked out a limbo between the right and the left and showed that it was a very good place to be. With exceptional efficiency and amiability he led a Court that put the brakes on some of the excesses of the Earl Warren era while keeping pace with the sentiments of a majority of the country—generally siding with economic conservatives and against cultural conservatives. As for judicial temperament, he was far more devoted to preserving tradition and majority rule than the generation of fire-breathing conservatives who followed him. And his administration of the Court was brilliantly if quietly effective, making him one of the most impressive chief justices of the past hundred years.

InThe Partisan: The Life of William Rehnquist,biographerJohn A. Jenkinswas critical of Rehnquist's history with racial discrimination. He noted that, as a private citizen, Rehnquist had protestedBrown v. Board of Education,and as a justice, consistently ruled against racial minorities inaffirmative actioncases. Only when white males began to makereverse discriminationclaims did he become sympathetic to equal protection arguments.[109]

Charles Friedhas described the Rehnquist Court's "project" as "to reverse not the course of history but the course of constitutional doctrine's abdication to politics".[110]Legal reporter Jan Greenburg has said that conservative critics noted that the Rehnquist Court did little to overturn the left's successes in the lower courts, and in some cases actively furthered them.[111]But in 2005, law professorJohn Yoowrote, "It is telling to see how many of Rehnquist's views, considered outside the mainstream at the time by professors and commentators, the court has now adopted."[112]

Personal health[edit]

After Rehnquist's death in 2005, theFBIhonored aFreedom of Information Actrequest detailing the Bureau's background investigation before Rehnquist's nomination as chief justice. The files reveal that for a period, Rehnquist had been addicted toPlacidyl,a drug widely prescribed forinsomnia.It was not until he was hospitalized that doctors learned of the extent of his dependency.

Freeman Cary, a U.S. Capitol physician, prescribed Rehnquist Placidyl for insomnia and back pain from 1972 to 1981 in doses exceeding the recommended limits, but the FBI report concluded that Rehnquist was already taking the drug as early as 1970.[113]By the time he sought treatment, Rehnquist was taking three times the prescribed dose of the drug nightly.[114]On December 27, 1981, Rehnquist enteredGeorge Washington University Hospitalfor treatment of back pain and Placidyl dependency. There, he underwent a monthlongdetoxificationprocess.[114]While hospitalized, he had typicalwithdrawalsymptoms, includinghallucinationsandparanoia.For example, "One doctor said Rehnquist thought he heard voices outside his hospital room plotting against him and had 'bizarre ideas and outrageous thoughts', including imagining 'aCIAplot against him' and seeming to see the design patterns on the hospital curtains change configuration. "[115]

For several weeks before his hospitalization, Rehnquist had slurred his words, but there were no indications he was otherwise impaired.[113][116]Law professorMichael Dorfobserved that "none of the Justices, law clerks or others who served with Rehnquist have so much as hinted that his Placidyl addiction affected his work, beyond its impact on his speech."[117]

Failing health and death[edit]

On October 26, 2004, the Supreme Court press office announced that Rehnquist had recently been diagnosed withanaplastic thyroid cancer.[118]In the summer of 2004, Rehnquist traveled to England to teach a constitutional law class atTulane University Law School's program abroad. After several months out of the public eye, Rehnquist administered the oath of office to PresidentGeorge W. Bushat hissecond inaugurationon January 20, 2005, despite doubts about whether his health would permit it. He arrived using a cane, walked very slowly, and left immediately after the oath was administered.[119]

Rehnquist missed 44 oral arguments before the Court in late 2004 and early 2005, returning to the bench on March 21, 2005.[120]He remained involved in Court business during his absence, participating in many decisions and deliberations.[121]

On July 1, 2005, Justice O'Connor announced her impending retirement from the Court after consulting with Rehnquist and learning that he had no intention to retire. To a reporter who asked whether he would be retiring, Rehnquist replied, "That's for me to know and you to find out."[122]

Rehnquist died at hisArlington, Virginia,home on September 3, 2005, at age 80. He was the first justice to die in office sinceRobert H. Jacksonin 1954 and the first chief justice to die in office sinceFred M. Vinsonin 1953.[123][124]He was also the last serving justice appointed by Nixon.

On September 6, 2005, eight of Rehnquist's former law clerks, includingJohn Roberts,his eventual successor, served aspallbearersas his casket was placed on thesame catafalquethat boreAbraham Lincoln's casket as helay in statein 1865.[125]Rehnquist's bodylay in reposein the Great Hall of theUnited States Supreme Court Buildinguntil his funeral on September 7, aLutheranservice conducted at theRoman CatholicCathedral of St. Matthew the Apostlein Washington, D.C. PresidentGeorge W. Bushand Justice O'ConnoreulogizedRehnquist, as did members of his family.[126]Rehnquist's funeral was the largest gathering of political dignitaries at the cathedral since PresidentJohn F. Kennedy's funeral in 1963. It was followed by a private burial service, in which he was interred next to his wife, Nan, atArlington National Cemetery.[127][128][129]

Replacement as Chief Justice[edit]

Rehnquist's death, just over two months after O'Connor announced her impending retirement, left two vacancies for President Bush to fill. On September 5, 2005, Bush withdrew the nomination of John Roberts of theD.C. Circuit Court of Appealsto replace O'Connor as associate justice and instead nominated him to replace Rehnquist as Chief Justice. Roberts was confirmed by the U.S. Senate and sworn in as the new chief justice on September 29, 2005. He had clerked for Rehnquist in 1980–1981.[130]O'Connor, who had made the effective date of her resignation the confirmation of her successor, continued to serve on the Court untilSamuel Alitowas confirmed and sworn in on January 31, 2006.

Eulogizing Rehnquist in theHarvard Law Review,Roberts wrote that he was "direct, straightforward, utterly without pretense—and a patriot who loved and served his country. He was completely unaffected in manner."[131]

Family life[edit]

Rehnquist's paternal grandparents immigrated separately fromSwedenin 1880. His grandfather Olof Andersson, who changed his surname from thepatronymicAndersson to thefamily nameRehnquist, was born in the province ofVärmland;his grandmother was born Adolfina Ternberg in theVreta Kloster parishinÖstergötland.Rehnquist is one of two chief justices ofSwedish descent,the other beingEarl Warren,who hadNorwegianand Swedish ancestry.[132]

Rehnquist married Natalie "Nan" Cornell on August 29, 1953. The daughter of a San Diego physician, she worked as an analyst on the CIA's Austria desk before their marriage.[133]The couple had three children: James, a lawyer and college basketball player;Janet,a lawyer; and Nancy, an editor (including of her father's books) and homemaker.[134][135]Nan Rehnquist died on October 17, 1991, aged 62, ofovarian cancer.[128]Rehnquist was survived by nine grandchildren.[136][137]

Shortly after moving to Washington, D.C., the Rehnquists purchased a home inGreensboro, Vermont,where they spent many vacations.[138]

Books authored[edit]

- The Centennial Crisis: The Disputed Election of 1876.New York: Knopf Publishing Group. 2004.ISBN0-375-41387-1.

- All the Laws but One: Civil Liberties in Wartime.New York: William Morrow & Co. 1998.ISBN0-688-05142-1.

- Grand Inquests: The Historic Impeachments of Justice Samuel Chase and President Andrew Johnson.New York: Knopf Publishing Group. 1992.ISBN0-679-44661-3.

- The Supreme Court: How It Was, How It Is.New York: William Morrow & Co. 1987.ISBN0-688-05714-4.

- The Supreme Court: A new edition of the Chief Justice's classic history(Revised ed.). New York: Knopf Publishing Group. 2001.ISBN0-375-40943-2.

See also[edit]

- List of justices of the Supreme Court of the United States

- List of law clerks of the Supreme Court of the United States (Chief Justice)

- List of law clerks of the Supreme Court of the United States (Seat 9)

- List of United States Supreme Court justices by time in office

- List of United States Supreme Court cases by the Burger Court

- List of United States Supreme Court cases by the Rehnquist Court

References[edit]

- ^Dean, John (February 2002).The Rehnquist Choice.Free Press.ISBN978-0-7432-2979-1.RetrievedApril 3,2022.

- ^abcJenkins, John A. (October 2, 2012).The Partisan: The life of William Rehnquist.PublicAffairs. pp. [search "flatly denied" in Google Books link – page numbers are not listed on preview].ISBN978-1-58648-888-8.RetrievedJanuary 3,2022.

- ^Herman J. Obermayer, Rehnquist: A Personal Portrait of the Distinguished Chief Justice of the United States (2009 Simon and Schuster) pp.24–26

- ^Rosen, Jeffrey (2005)."Rehnquist the Great?".The Atlantic.Archivedfrom the original on May 10, 2010.RetrievedMay 30,2010.

- ^It means, in direct translation to English:reindeer twig.

- ^abLane, Charles (2005)."Head of the Class".Stanford Magazine.No. July/August. Archived fromthe originalon March 16, 2008.

So, for the brainy kid they had called 'Bugs' back home at suburban Shorewood High School, just outside Milwaukee, weather was a key criterion in selecting a college.

- ^"Illinois General Assembly - Full Text of HR0622".www.ilga.gov.Archivedfrom the original on October 16, 2016.RetrievedOctober 16,2016.

- ^abcChristopher L. Tomlins (2005).The United States Supreme Court.Houghton Mifflin.ISBN978-0-618-32969-4.RetrievedOctober 21,2008.

- ^"Volume 04 (1951-1952)".

- ^Jenkins, John A. (October 2, 2012).The Partisan: The Life of William Rehnquist.PublicAffairs. pp. 16–17.ISBN978-1-58648-887-1.RetrievedApril 23,2022.

- ^Biskupic, Joan.Sandra Day O'Connor: How the First Woman on the Supreme Court became its most influential justice.New York: Harper Collins, 2005

- ^Totenburg, Nina (October 31, 2018)."O'Connor, Rehnquist And A Supreme Marriage Proposal".NPR.Archivedfrom the original on October 31, 2018.RetrievedOctober 31,2018.

- ^Biskupic, Joan(September 4, 2005)."Rehnquist left Supreme Court with conservative legacy".USA Today.Archived fromthe originalon October 22, 2012.RetrievedApril 29,2023.

- ^William Rehnquist."A Random Thought on the Segregation Cases"(PDF).Archived(PDF)from the original on November 1, 2018.RetrievedNovember 14,2017.,S. Hrg. 99-1067, Hearings Before the Senate Committee on the Judiciary on the Nomination of Justice William Hubbs Rehnquist to be Chief Justice of the United States (July 29–31, and August 1, 1986).

- ^1971 confirmation hearings.[citation needed]

- ^"132 Cong. Rec. 23548 (Speech of Senator Paul Sarbanes)"(PDF).Library of Congress.1986.Archived(PDF)from the original on October 1, 2007.RetrievedDecember 29,2017.

- ^Schwartz, Bernard (1996).Decision: How the Supreme Court Decides Cases.OUP USA. p. 96.ISBN978-0-19-511800-1.

- ^Liptak, Adam (September 11, 2005)."The Memo That Rehnquist Wrote and Had to Disown".The New York Times.RetrievedApril 29,2023.

- ^Canellos, Peter S. (August 23, 2005)."Memos may not hold Roberts's opinions".Boston.com.RetrievedFebruary 20,2023.

- ^Schwartz, Bernard (1988). "Chief Justice Rehnquist, Justice Jackson, and the" Brown "Case".Supreme Court Review.1988(1988): 245–267.doi:10.1086/scr.1988.3109626.ISSN0081-9557.JSTOR3109626.S2CID147205671.

- ^Kluger, Richard (1976).Simple Justice: The History ofBrown v. Board of Educationand Black America's Struggle for Equality.note 4. pp.606.ISBN978-0-394-47289-8.

{{cite book}}:CS1 maint: location (link) CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^abcdefg"Reagan's Mr. Right".TIME.June 30, 1986.Archivedfrom the original on August 9, 2021.RetrievedAugust 9,2021.

- ^Snyder, Brad; Barrett, John Q. (2012)."Rehnquist's Missing Letter: A Former Law Clerk's 1955 Thoughts on Justice Jackson and Brown".The Boston College Law Review.53(2): 631–660. Archived fromthe originalon July 17, 2017.RetrievedSeptember 17,2014.

- ^"Cases where Justice Rehnquist has cited Brown v. Board of Education in support of a proposition"ArchivedMarch 21, 2017, at theWayback Machine,S. Hrg. 99-1067, Hearings Before the Senate Committee on the Judiciary on the Nomination of Justice William Hubbs Rehnquist to be Chief Justice of the United States (July 29, 30, 31, and August 1, 1986).

- ^abRosen, Jeffery (April 2005)."Rehnquist the Great?".Atlantic Monthly.Archivedfrom the original on January 4, 2010.RetrievedMarch 12,2017.( "Rehnquist ultimately embraced the Warren Court'sBrowndecision, and after he joined the Court he made no attempt to dismantle the civil-rights revolution, as political opponents feared he would ").

- ^"Terry v. Adams,345 U.S. 461 (1953) ".Findlaw.RetrievedApril 29,2023.

- ^Yarbrough, Tinsley E. (2000).The Rehnquist Court and the Constitution.Oxford University Press. p. 2.ISBN978-0-19-535602-1.

- ^Mark Silva (2008).McCain: The Essential Guide to the Republican Nominee: His Character, His Career and Where He Stands.Triumph Books. p.44.ISBN978-1-60078-196-4.

- ^McLellan, Dennis (October 24, 2002)."Denison Kitchel, 94; Ran Goldwater's Presidential Bid".Los Angeles Times.Archivedfrom the original on November 6, 2013.RetrievedJune 2,2013.

- ^Gordon, David(Fall 2001)."Before the Storm: Barry Goldwater and the Unmaking of the American Consensus"ArchivedFebruary 19, 2013, at theWayback Machine.Mises Review.

- ^Roddy, Dennis (December 2, 2000)."Just Our Bill"ArchivedMay 22, 2010, at theWayback Machine.Pittsburgh Post-Gazette.

- ^Wilentz, Amy (August 11, 1986)."Through the Wringer".Time.Archived fromthe originalon October 22, 2007.RetrievedFebruary 20,2023.

- ^"LII: US Supreme Court: Justice Rehnquist".Supct.law.cornell.edu.Archivedfrom the original on September 26, 2008.RetrievedSeptember 19,2008.

- ^Jeffrey Rosen (November 4, 2001)."Renchburg's the One!".The New York Times.RetrievedSeptember 19,2008.

- ^abDean, John (February 2002).The Rehnquist Choice.Free Press. p. 5.ISBN978-0-7432-2979-1.RetrievedJune 30,2022.

- ^abDean, John (February 2002).The Rehnquist Choice.Free Press. p. 6.ISBN978-0-7432-2979-1.RetrievedJune 30,2022.

- ^abcDean, John (February 2002).The Rehnquist Choice.Free Press. p. 7.ISBN978-0-7432-2979-1.RetrievedJune 30,2022.

- ^Dean, John (February 2002).The Rehnquist Choice.Free Press. p. 10.ISBN978-0-7432-2979-1.RetrievedJune 30,2022.

- ^"Was Rehnquist 'Deep Throat'?".Thehill.com. Archived fromthe originalon January 14, 2008.RetrievedSeptember 19,2008.

- ^Nixon, Richard (October 21, 1971)."Address to the Nation Announcing Intention To Nominate Lewis F. Powell Jr. and William H. Rehnquist To Be Associate Justices of the Supreme Court of the United States".The American Presidency Project.University of California, Santa Barbara.Archivedfrom the original on March 10, 2016.RetrievedOctober 25,2022.

- ^Perlstein, Rick (2008), p. 605

- ^abcdefgMcMillion, Barry J.; Rutkus, Denis Steven (July 6, 2018)."Supreme Court Nominations, 1789 to 2017: Actions by the Senate, the Judiciary Committee, and the President"(PDF).Washington, D.C.: Congressional Research Service.RetrievedMarch 9,2022.

- ^abMcMillion, Barry J. (January 28, 2022).Supreme Court Nominations, 1789 to 2020: Actions by the Senate, the Judiciary Committee, and the President(PDF)(Report). Washington, D.C.: Congressional Research Service.RetrievedFebruary 19,2022.

- ^Barrett, John Q. (Spring 2007)."The" Federalism Five "as Supreme Court Nominees, 1971-1991".Journal of Civil Rights and Economic Development.21(2): 486.RetrievedFebruary 19,2022– via St. John's Law Scholarship Repository.

- ^"U.S. Senate: Cloture Motions - 92nd Congress".www.senate.gov.United States Senate.RetrievedMarch 10,2022.

- ^ab"Supreme Court Nominations (1789-Present)".Washington, D.C.: United States Senate.RetrievedFebruary 19,2022.

- ^ab"Justices 1789 to Present".Washington, D.C.: Supreme Court of the United States.RetrievedFebruary 19,2022.

- ^abcdBob Woodward & Scott Armstrong,The Brethren: Inside the Supreme Court.1979. Simon and Schuster. Page 221.

- ^Bob Woodward & Scott Armstrong,The Brethren: Inside the Supreme Court.1979. Simon and Schuster. Page 222.

- ^abcFriedman, Leon.The Justices of the United States Supreme Court: Their Lives and Major Opinions,Volume V. Chelsea House Publishers. 1978. Page 114.

- ^"A Random Thought on the Segregation Cases".PBS.Archivedfrom the original on October 16, 2016.RetrievedSeptember 18,2017.

- ^abBob Woodward & Scott Armstrong,The Brethren: Inside the Supreme Court.1979. Simon and Schuster. Page 411.

- ^ab"Trimble v. Gordon,430 U.S. 762 (1977) ".Findlaw.RetrievedFebruary 20,2023.

- ^Bob Woodward & Scott Armstrong,The Brethren: Inside the Supreme Court.1979. Simon and Schuster. Page 235.

- ^Friedman, Leon.The Justices of the United States Supreme Court: Their Lives and Major Opinions,Volume V. Chelsea House Publishers. 1978. Page 124.

- ^Friedman, Leon.The Justices of the United States Supreme Court: Their Lives and Major Opinions,Volume V. Chelsea House Publishers. 1978. Page 122.

- ^abFriedman, Leon.The Justices of the United States Supreme Court: Their Lives and Major Opinions,Volume V. Chelsea House Publishers. 1978. Page 113.

- ^Von Drehle, David (July 19, 1993)."Redefining Fair With a Simple Careful Assault. Step-by-Step Strategy Produced Strides for Equal Protection".The Washington Post.Archivedfrom the original on February 25, 2017.RetrievedSeptember 18,2017.

- ^abcdeFriedman, Leon.The Justices of the United States Supreme Court: Their Lives and Major Opinions,Volume V. Chelsea House Publishers. 1978. Page 115.

- ^abcdefFriedman, Leon.The Justices of the United States Supreme Court: Their Lives and Major Opinions,Volume V. Chelsea House Publishers. 1978. Page 116.

- ^Friedman, Leon.The Justices of the United States Supreme Court: Their Lives and Major Opinions,Volume V. Chelsea House Publishers. 1978. Pages 116–117.

- ^abcDavid Garrow, "The Rehnquist Reins",New York Times,October 6, 1996.

- ^Undated 2003–04Charlie Rose Showinterview with Rehnquist.

- ^Woodward & Armstrong, The Brethren 267 (2005) (1979 ed. at __).

- ^The Brethren,2005 ed. at 498 (1979 ed. at ___).

- ^The Brethren,2005 ed. at 268, 499 (1979 ed. at 407–8, __)

- ^Leon Friedman,The Justices of the United States Supreme Court: Their Lives and Major Opinions(1978), page 121.

- ^abThe Brethren,2005 ed. at 268 (1979 ed. at 222).

- ^"Jefferson v. Hackney, 406 U.S. 535 (1972)".Justia Law.RetrievedFebruary 20,2023.

- ^The Brethren,2005 ed. at __ (1979 ed. at 222, 408.

- ^abThe Brethren,2005 ed. at 499.

- ^Stern, Seth; Wermiel, Stephen (2013).Justice Brennan: Liberal Champion.University Press of Kansas. p. 475.ISBN978-0-7006-1912-2.

- ^The Brethren,2005 ed. at __ (1979 ed. at 269).

- ^Eisler, Kim Isaac (1993).A Justice for All: William J. Brennan, Jr., and the decisions that transformed America.p. 272. New York: Simon & Schuster.ISBN0-671-76787-9

- ^abRutkus, Denis Steven; Tong, Lorraine H. Tong (March 17, 2005).The Chief Justice of the United States: Responsibilities of the Office and Process for Appointment(Report). Washington, D.C.: Congressional Research Service.RetrievedFebruary 19,2022– via University of North Texas Libraries Government Documents Department.

- ^Alan S. Oser,"Unenforceable Covenants are in Many Deeds"ArchivedOctober 22, 2007, at theWayback Machine,New York Times(August 1, 1986).

Mr. Rehnquist has said he was unaware of discriminatory restrictions on properties he bought in Arizona andVermont,and officials in those states said today that he had never even been required to sign the deeds that contained the restrictions.... He told the committee he would act quickly to get rid of the covenants. The restriction on the Vermont property prohibits the lease or sale of the property to "members of the Hebrew race"... The discriminatory language appears on the first page of the single-spaced document in the middle of a long paragraph filled with unrelated language regarding sewers and the construction of a mailbox.

- ^abKamen, Al (September 18, 1986)."Rehnquist Confirmed In 65-33 Senate Vote".The Washington Post.RetrievedFebruary 19,2022.

- ^Taylor Jr, Stuart (August 1, 1986)."President Asserts He Will Withhold Rehnquist Memos".The New York Times.ISSN0362-4331.RetrievedFebruary 20,2023.

- ^"Chief justice has presided over only one other trial".Deseret News.Associated Press. January 10, 1999.Archivedfrom the original on November 12, 2020.RetrievedOctober 29,2020.

- ^"Julian D. Heislup, Sr. and Linda L. Dixon, Appellees, v. Town of Colonial Beach, Virginia; Bernard George Denson, individually and in Official Capacity As Member of Councilof Town of Colonial Beach; Gloria T. Fenwick, Individuallyand in Official Capacity As Member of Council of Town Ofcolonial Beach; Edna C. Sydnor, Individually and Inofficial Capacity As Member of Council of Town of Colonialbeach; Thomas B. Rogers, Individually and in Officialcapacity As Member of Council of Town of Colonial Beach;john A. Anderson, Individually and in Official Capacity Aschief of Police of Town of Colonial Beach; Marty J. Perry, individually and in Official Capacity As Police Officer Withtown of Colonial Beach and Leroy H. Bernard, Appellants, andjosef W. Dunn, Individually and in Official Capacity As Townmanager of the Town of Colonial Beach, Defendant.conrad B. Mattox, Jr. and S. Keith Barker, Appellants, julian D. Heislup, Sr. and Linda L. Dixon, Appellants, v. Town of Colonial Beach, Virginia; Bernard George Denson, individually and in His Official Capacity As Member Ofcouncil of Town of Colonial Beach; Gloria T. Fenwick, individually and in Her Official Capacity As Member Ofcouncil of Town of Colonial Beach; Edna C. Syndor, individually and in Her Official Capacity As Member Ofcouncil of Town of Colonial Beach; Thomas B. Rogers, individually and in His Official Capacity As Member Ofcouncil of Town of Colonial Beach; John A. Anderson, individually and in His Official Capacity As Chief of Policeof Town of Colonial Beach; Josef W. Dunn, Individually Andin His Official Capacity As Town Manager of the Town Ofcolonial Beach; Marty J. Perry, Individually and in Hisofficial Capacity As Police Officer with Town of Colonialbeach and Leroy H. Bernard, Appellees, 813 F.2d 401 (4th Cir. 1986)".Justia Law.Archivedfrom the original on July 5, 2017.RetrievedOctober 29,2020.

- ^Toobin, Jeffrey.The Nine: Inside the Secret World of the Supreme Court.New York: Anchor Books, 2007.

- ^Barrett, John Q. (2008)."A Rehnquist Ode on the Vinson Court (Circa Summer 1953)".The Green Bag.11.Rochester, NY: 290.SSRN1132427.

- ^McElroy, Lisa Tucker.John G. Roberts, Jr.Minneapolis: Lerner Publications, 2007.

- ^"Rehnquist's Federalist Legacy".Cato.org.Archivedfrom the original on September 16, 2005.RetrievedSeptember 19,2008.

- ^Crawford, Jan.Supreme Conflict: The Inside Story of the Struggle for Control of the United States Supreme Court.2007. Penguin Books. Page 29.

- ^"Archived copy"(PDF).Archived(PDF)from the original on February 3, 2021.RetrievedJune 2,2014.

{{cite web}}:CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^Greenhouse, Linda (September 5, 2005)."William H. Rehnquist, Architect of Conservative Court, Dies at 80".The New York Times.Archivedfrom the original on November 14, 2017.RetrievedNovember 13,2017.

- ^Age Discrimination in Employment Law.Barbara Lindemann and David D. Kadue. Page 699. 2003, Washington, D.C.

- ^"Archived copy".Archivedfrom the original on March 1, 2014.RetrievedJune 2,2014.

{{cite web}}:CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^Chemerinsky, Erwin(March 11, 2005)Keynote Address: Rehnquist Court's Federalism RevolutionArchivedDecember 5, 2020, at theWayback Machine,41Willamette Law Review827

- ^Roh, Jane (May 19, 2015)."Rehnquist's Legacy: A Balanced Court".Fox News.RetrievedApril 29,2023.

- ^"Planned Parenthood of Southeastern Pa. v. Casey".Cornell Law School.June 29, 1992.RetrievedMarch 5,2009.

- ^Murdoch, Joyce; Price, Deborah (May 16, 2001).Courting Justice: Gay men and Lesbians v. The Supreme Court.Basic Books. p. 203.ISBN978-0-465-01514-6.

- ^Rehnquist, William."Ratchford v. Gay Lib".Oyez.RetrievedApril 10,2022.

- ^"Bowers v. Hardwick".Oyez.RetrievedMay 8,2022.

- ^"Weaver v. Nebo School District".Acluutah.org.Archivedfrom the original on May 4, 2008.RetrievedSeptember 19,2008.

- ^abc"Lawrence V. Texas".Law.cornell.edu.Archivedfrom the original on July 23, 2008.RetrievedSeptember 19,2008.

- ^Webster v. Doe,486 U.S. 592 (1988).

- ^Oncale v. Sundowner Offshore Services, Inc.,523 US 75 (1998).

- ^"Board of Regents v. Southworth,529 U.S. 217 (2000) ".Findlaw.RetrievedFebruary 20,2023.

- ^Fitzsimons, Tim."LGBT History Month:The early days of America's AIDS crisis".NBC.RetrievedJune 27,2022.

- ^abGreenhouse, Linda (July 3, 1992)."Souter Anchoring the Court's New Center".The New York Times.Archivedfrom the original on February 1, 2009.RetrievedJune 27,2008.

- ^abcde"University of Chicago Law School > News 09.06.2005: Stone Says Rehnquist's Legacy Does not Measure Up".Law.uchicago.edu. August 16, 2010.Archivedfrom the original on August 8, 2021.RetrievedAugust 8,2021.

- ^"United States v. Virginia,518 U.S. 515 (1996) ".Findlaw.RetrievedFebruary 20,2023.

- ^abc"United States v. Virginia – 518 U.S. 515 (1996):: Justia US Supreme Court Center".Supreme.justia.com.Archivedfrom the original on October 22, 2008.RetrievedApril 22,2013.

- ^Robenalt, James (January 22, 2020)."Why Is John Roberts Even in the Impeachment Trial?".Politico.RetrievedDecember 19,2022.

- ^McDonald, Forrest (June 14, 1992)."The Senate Was Their Jury".The New York Times.RetrievedDecember 29,2022.

- ^Rosen, Jeffery (April 2005)."Rehnquist the Great".The Atlantic.Archivedfrom the original on January 4, 2010.RetrievedMarch 12,2017.

- ^Adarand Constructors v. Pena,515 U.S. 200 (1995);City of Richmond v. J.A. Croson Co.,488 U.S. 469 (1989);Regents of the Univ. of Calif. v. Bakke,438 U.S. 265 (1978).

- ^Fried, Charles (2004).Saying What the Law Is: The Constitution in the Supreme Court.pp. 46–47.ISBN978-0-674-01954-6

- ^Greenburg, Jan Crawford.Supreme Conflict: The Inside Story of the Struggle for Control of the United States Supreme Court.2007. Penguin Books. p. 29.

- ^ Yoo, John (April 27, 2005)."He Advocated Limitations of Public Power".Philadelphia Inquirer.Archived fromthe originalon April 28, 2005.RetrievedOctober 27,2008.

- ^abMauro, Tony (January 4, 2007)."Rehnquist FBI File Sheds New Light on Drug Dependence, Confirmation Battles".Legal Times.RetrievedFebruary 20,2023.

- ^ab"FBI releases Rehnquist drug problem records".NBC News(Press release). Associated Press. August 8, 2020.RetrievedFebruary 20,2023.

- ^Cooperman, Alan (January 5, 2007)."Sedative Withdrawal Made Rehnquist Delusional in '81".The Washington Post.p. A01.Archivedfrom the original on November 6, 2012.RetrievedMarch 15,2008.

- ^Shafer, Jack (September 9, 2005)."Rehnquist's Drug Habit".Slate.ISSN1091-2339.RetrievedFebruary 20,2023.

- ^Dorf, Michael C."The Big News in the Rehnquist FBI File: There Is None".FindLaw.RetrievedFebruary 20,2023.

- ^Altman, Lawrence (November 26, 2004)."Prognosis for Rehnquist Depends on Which Type of Thyroid Cancer He Has".The New York Times.Archivedfrom the original on November 17, 2017.RetrievedNovember 16,2017.

- ^Nina Totenberg."Ailing Rehnquist Administers Oath of Office".NPR.Archivedfrom the original on January 11, 2009.RetrievedSeptember 19,2008.

- ^"Online NewsHour: Rehnquist Returns to Bench as Supreme Court Reviews Restraining Order Case – March 21, 2005".Pbs.org.Archivedfrom the original on August 11, 2010.RetrievedSeptember 19,2008.

- ^"Chief Justice Rehnquist Returns to Court".Fox News. March 21, 2005.Archivedfrom the original on July 18, 2008.RetrievedSeptember 19,2008.

- ^"D.C. Wonders When Rehnquist Will Go".Fox News.July 10, 2005. Archived fromthe originalon March 12, 2007.RetrievedFebruary 20,2023.

- ^Chapman, Roger; Ciment, James (2015).Culture Wars: An Encyclopedia of Issues, Viewpoints and Voices.Routledge.ISBN978-1-317-47351-0.

- ^Ward, Artemus; Brough, Christopher; Arnold, Robert (2015).Historical Dictionary of the U.S. Supreme Court.Rowman & Littlefield.ISBN978-0-8108-7521-0.Archivedfrom the original on February 8, 2020.RetrievedNovember 20,2017.

- ^Richard W. Stevenson; David Stout (September 6, 2005)."Roberts Hearing Set for Monday; Rehnquist's Coffin Lies in Court".The New York Times.Archived fromthe originalon April 17, 2009.RetrievedSeptember 19,2008.

- ^Lane, Charles(September 8, 2005)."Rehnquist Eulogies Look Beyond Bench".The Washington Post.Archivedfrom the original on March 4, 2016.RetrievedJuly 3,2010.

- ^Weil, Martin; Jackman, Tom (September 5, 2005)."Funeral Set for Wednesday At St. Matthew's Cathedral".The Washington Post.Archivedfrom the original on November 6, 2012.RetrievedSeptember 19,2008.

- ^ab"William Rehnquist".www.arlingtoncemetery.mil.RetrievedFebruary 20,2023.

- ^Christensen, George A.,Journal of Supreme Court HistoryVolume 33 Issue 1, pp. 17–41 (February 19, 2008),Here Lies the Supreme Court: Revisited,University of Alabama.

- ^Adam Liptak And Todd S. Purdum (July 31, 2005)."As Clerk for Rehnquist, Nominee Stood Out for Conservative Rigor".The New York Times.Archivedfrom the original on October 15, 2008.RetrievedSeptember 19,2008.

- ^Roberts, John G.(November 2005)."In Memoriam: William H. Rehnquist"(PDF).Harvard Law Review.119(1): 1.ISSN0017-811X.Archived(PDF)from the original on May 8, 2013.RetrievedNovember 14,2017.

- ^"Speech Chief Justice William H. Rehnquist".supremecourt.gov. April 9, 2001.Archivedfrom the original on July 23, 2011.RetrievedSeptember 19,2008.

- ^Obermayer at p. xvi

- ^Obermayer at p. xv

- ^Lane, Charles (September 6, 2005)."Emotion Overcomes Sober Court".The Washington Post.Archivedfrom the original on November 10, 2012.RetrievedMay 28,2010.

- ^Totenberg, Nina (September 8, 2005)."Family, Peers Pay Respects to Rehnquist".NPR.org.National Public Radio.Archivedfrom the original on January 15, 2012.RetrievedMay 28,2010.

- ^Levine, Susan and Charles Lane (September 7, 2005)."For Chief Justice, A Final Session With His Court".The Washington Post.Archivedfrom the original on June 4, 2012.RetrievedMay 28,2010.

- ^Obermayer, pp. 56–58

Further reading[edit]

- Abraham, Henry J. (1992).Justices and Presidents: A Political History of Appointments to the Supreme Court(3rd ed.). New York:Oxford University Press.ISBN0-19-506557-3.

- Cushman, Clare (2001).The Supreme Court Justices: Illustrated Biographies, 1789–1995(2nd ed.). (Supreme Court Historical Society,Congressional Quarterly Books).ISBN1-56802-126-7.