Wu Lien-teh

Wu Lien-teh | |

|---|---|

Ngũ liên đức | |

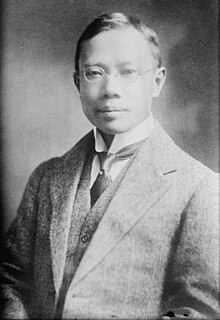

Portrait of Dr. Wu Lien-Teh | |

| Born | 10 March 1879 |

| Died | 21 January 1960(aged 80) |

| Other names | Goh Lean Tuck, Ng Leen Tuck |

| Education | University of Cambridge- Bachelor of Medicine and Bachelor of Surgery Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine- Postgraduate Diploma in Bacteriology University of Halle- Advance Diploma in Bacteriological Studies Pasteur Institute- Master of Medicine in Infectious Diseases University of Cambridge- Master of Medicine University of Cambridge- Doctor of Medicine |

| Occupation(s) | Medical Doctor, Physician, Researcher |

| Years active | 1903–1959 |

| Known for | Work on theManchurian Plague of 1910–11 |

| Notable work | Plague Fighter: The Autobiography of a Modern Chinese Physician |

| Children | 7 |

| Wu Lien-teh | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | Ngũ liên đức | ||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | Ngũ liên đức | ||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

Wu Lien-teh(Chinese:Ngũ liên đức;pinyin:Wǔ Liándé;Jyutping:Ng5Lin4Dak1;Pe̍h-ōe-jī:Gó͘ Liân-tek;Goh Lean TuckandNg Leen TuckinMinnanandCantonesetransliterationrespectively; 10 March 1879 – 21 January 1960) was aMalayanphysicianrenowned for his work inpublic health,particularly theManchurian plagueof 1910–11. He is the inventor of the Wu mask, which is the forerunner of today'sN95 respirator.

Wu was the first medical student ofChinese descentto study at theUniversity of Cambridge.[1]He was also the first Malayan nominated for theNobel PrizeinPhysiology or Medicine,in 1935.[2]

Life and education

[edit]Wu was born inPenang,one of the three towns of theStraits Settlements(the others beingMalaccaandSingapore), currently as one of the states ofMalaysia.The Straits Settlements formed part of the colonies of theUnited Kingdom.His father was a recent immigrant fromTaishan,China,and worked as agoldsmith.[3][4]Wu's mother's was ofHakkaheritage and was a second-generationPeranakanborn in Malaya.[5]Wu had four brothers and six sisters. His early education was at thePenang Free School,aChurch of Englandschool.[4]

Wu was admitted toEmmanuel College, Cambridgein 1896,[6]after winning theQueen's Scholarship.[3]The women in his family made him a version of his college’s lion crest inPerakanan beadworkas a leaving gift.[7][8]He had a successful career at university, winning virtually all the available prizes and scholarships. His undergraduate clinical years were spent atSt Mary's Hospital, Londonand he then continued his studies at theLiverpool School of Tropical Medicine(underSir Ronald Ross), thePasteur Institute,Halle University,and the Selangor Institute.[3]

Wu returned to the Straits Settlements in 1903. Some time after that, he married Ruth Shu-chiung Huang, whose sister was married toLim Boon Keng,a physician who promoted social and educational reforms inSingapore.[4]The sisters were daughters ofWong Nai Siong,a Chinese revolutionary leader and educator who had moved to the area from 1901 to 1906.[4]

Wu and his family moved to China in 1907.[4]During his time in China, Wu's wife and two of their three sons died.[4]While Ms Huang lived in Peking, Wu started a second family in Shanghai with Marie Lee Sukcheng, whom he had met in Manchuria.[1]Wu had four children with Lee.

During theJapanese invasion of Manchuria,in November 1931, Wu was detained and interrogated by the Japanese authorities under suspicion of being a Chinese spy.[4]

In 1937, during theJapanese occupation of much of Chinaand the retreat of the Nationalists, Wu was forced to flee, returning to the Settlements to live inIpoh.His home and all his ancient Chinese medical books were burnt.[9][4]

In 1943 Wu was captured by Malayan left-wing resistance fighters and held for ransom. Then he nearly was prosecuted by the Japanese for supporting the resistance movement by paying the ransom, but was protected by having treated a Japanese officer.[4]

Career

[edit]In September 1903, Wu joined the Institute for Medical Research in Kuala Lumpur as the first research student. However, there was no specialist post for him because, at that time, a two-tier medical system in the British colonies provided that only British nationals could hold the highest positions of fully qualified medical officers or specialists. Wu spent his early medical career researchingberi-beriand roundworms (Ascarididae) before entering private practice toward the end of 1904 inChulia Street, George Town,Penang.[5]

Opium

[edit]Wu was a vocal commentator on the social issues of the time. In the early 1900s, he became friends with Lim Boon Keng andSong Ong Siang,a lawyer who was active in developing Singapore's civil society. He joined them in editingThe Straits Chinese Magazine.[4]With his friends, Wu founded the Anti-Opium Association in Penang. He organised a nationwideanti-opiumconference in the spring of 1906 that was attended by approximately 3000 people.[10][4]This attracted the attention of the powerful forces involved in the lucrative trade ofopiumand, in 1907, this led to a search and subsequent discovery of one ounce of tincture of opium in Wu's dispensary, for which he was convicted and fined.[4]

In 1908, Dr Wu accepted the then Grand CouncillorYuan Shikai's offer to become the Vice Director of the Imperial Army Medical College, now known as theArmy Medical College,based inTianjin,in 1908. This was established to train doctors for the Chinese Army.[3]

Pneumonic plague

[edit]In the winter of 1910, Wu was given instructions from the Foreign Office of the Imperial Qing court[11]in Peking, to travel toHarbinto investigate an unknown disease that killed 99.9% of its victims.[12]This was the beginning of the largepneumonic plagueepidemic of Manchuria and Mongolia, which ultimately claimed 60,000 lives.[13]

Wu was able to conduct apostmortem(usually not accepted in China at the time) on aJapanesewoman who had died of the plague.[4][14]Having ascertained via the autopsy that the plague wasspreading by air,Wu developedsurgical masksinto more substantial masks with layers ofgauzeand cotton to filter the air.[15][16]Gérald Mesny, a prominent French doctor who had come to replace Wu, refused to wear a mask and died days later of the plague.[14][15][4]The mask was widely produced, with Wu overseeing the production and distribution of 60,000 masks in a later epidemic, and it featured in many press images.[17][15]

Wu initiated a quarantine, arranged for buildings to be disinfected, and the old plague hospital to be burned down and replaced.[4]The measure that Wu is best remembered for was in asking for imperial sanction to cremate plague victims.[4]It was impossible to bury the dead because the ground was frozen, and the bodies could only be disposed of by soaking them inparaffinand burning them on pyres.[3]Cremation of these infected victims turned out to be the turning point of the epidemic; days after cremations began, plague began to decline and within months it had been eradicated.[18]

Wu chaired the International Plague Conference in Mukden (Shenyang) in April 1911, a historic event attended by scientists from the United States of America, the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, France, Germany, Italy, Austria-Hungary, the Netherlands, Russia, Mexico, and China.[19][20]The conference took place over three weeks and featured demonstrations and experiments.

Wu later presented a plague research paper at the International Congress of Medicine, London in August 1911 which was published inThe Lancetin the same month.

At the plague conference,epidemiologistsDanylo ZabolotnyandAnna Tchourilinaannounced that they had traced the initial cause of the outbreak toTarbagan marmothunters who had contracted the disease from the animals. A tarabagan became the conference mascot.[19]However, Wu raised the question of why traditional marmot hunters had not experienced deadly epidemics before. He later published a work arguing that the traditionalMongolandBuryathunters had established practices that kept their communities safe and he blamed more recentShandongimmigrants to the area (Chuang Guandong) for using hunting methods that captured more sick animals and increased risk of exposure.[21]

Later career

[edit]This articleis missing informationabout this seems to be missing information about his life post WWII, a pivotal time in history.(March 2021) |

In 1912, Wu became the first director of the Manchurian Plague Service. He was a founder member and first president of theChinese Medical Association(1916–1920).[3][22]

Wu led the efforts to combat the1920-21 cholera pandemicin the north-east of China.[4]

In 1929, he was appointed a trustee of the 'Nanyang Club' inPenangbyCheah Cheang Lim,along withWu Lai Hsi,Robert Lim Kho Seng,andLim Chong Eang.The 'Nanyang Club', an old house inBeiping, China,provided convenient accommodation tooverseas Chinesefriends.[10]

In the 1930s he became the first director of the National Quarantine Service.[3]

Around 1939, Wu moved back to Malaya and continued to work as a general practitioner inIpoh.[4]

Wu collected donations to start the Perak Library (Now the Tun Razak Library) in Ipoh, a free-lending public library, and donated toShanghai City Libraryand theUniversity of Hong Kong.[4]

Wu was amandarinof the second rank[clarification needed]and sat on advisory committees for theLeague of Nations.He was given awards by the Czar of Russia and the President of France, and was awarded honorary degrees byJohns Hopkins University,Peking University,University of Hong Kong,andUniversity of Tokyo.[3][4]

Death and commemoration

[edit]Wu practised medicine until his death at the age of 80. He had bought a new house in Penang for his retirement and had just completed his 667-page autobiography,Plague Fighter, the Autobiography of a Modern Chinese Physician.[12]On 21 January 1960, he died of a stroke while in his home in Penang.[5]

A road named after Wu can be found in Ipoh Garden South, a middle-class residential area in Ipoh. In Penang, a residential area named Taman Wu Lien Teh is located near thePenang Free School.[23]In that school, his alma mater, a house has been named after him. There is a Dr. Wu Lien-teh Society, Penang.[24][25]

The Wu Lien-teh Collection, which comprises 20,000 books, was given by Wu to theNanyang University,which later became part of theNational University of Singapore.[5]

TheArt Museumof theUniversity of Malayahas a collection of Wu's paintings.[4]

In 1995, Wu's daughter, Dr. Yu-lin Wu, published a book about her father,Memories of Dr. Wu Lien-teh, Plague Fighter.[26]

In 2015, the Wu Lien-Teh Institute opened atHarbin Medical University.[14]In 2019,The Lancetlaunched an annual Wakley-Wu Lien Teh Prize in honour of Wu and the publication's founding editor,Thomas Wakley.[27]

Dr. Wu Lien-teh is regarded as the first person to modernise China's medical services and medical education. InHarbin Medical University,bronze statues of him commemorate his contributions to public health, preventive medicine, and medical education.[28]

Places named after Wu Lien-Teh

[edit]- Dr Wu Lien-Teh Centre for Research on Communicable Diseases,Universiti Tunku Abdul Rahman

- Wu Lien-Teh Institute,Harbin Medical University

Commemoration during the COVID-19 pandemic

[edit]Wu's work in the field ofepidemiologyhad contemporary relevance during theCOVID-19 pandemic.[15][25][29]

In May 2020, Dr.Yvonne Hounited the 22 known "medical and scientific descendants" of Dr. Wu Lien-Teh for a video conference meeting spanning 14 cities around the world.[30][31]In July 2020, some of these medical and scientific descendants collaborated to publish an article to memorialize Dr. Wu's lifetime work in public health.[32]In August 2020, a second group of Wu's medical and scientific descendants collaborated on a similar piece.[33]

In March 2021, Wu was honoured with aGoogle Doodle,depicting Wu assembling surgical masks and distributing them to reduce the risk of disease transmission.[34][35][36]

References

[edit]- ^abWu, Lien-teh (1959).Plague fighter: the autobiography of a modern Chinese physician.Cambridge, England: W. Heffer.

- ^Wu, Lien-Teh (April 2020)."The Nomination Database for the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, 1901–1953".

- ^abcdefgh"Obituary: Wu Lien-Teh".The Lancet.Originally published as Volume 1, Issue 7119.275(7119): 341. 6 February 1960.doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(60)90277-4.ISSN0140-6736.

- ^abcdefghijklmnopqrstuLee, Kam Hing; Wong, Danny Tze-ken; Ho, Tak Ming; Ng, Kwan Hoong (2014)."Dr Wu Lien-teh: Modernising post-1911 China's public health service".Singapore Medical Journal.55(2): 99–102.doi:10.11622/smedj.2014025.PMC4291938.PMID24570319.

- ^abcd"Wu Lien Teh ngũ liên đức – Resource Guides".National Library Singapore.26 September 2018.Retrieved26 March2020.

- ^"Tuck, Gnoh Lean (Wu Lien-Teh) (TK896GL)".A Cambridge Alumni Database.University of Cambridge.

- ^Cheah, Hwei-Fe'n (2017).Nyonya needlework: embroidery and beadwork in the Peranakan world.Alan Chong, Richard Lingner, Asian Civilisations Museum. Singapore.ISBN978-981-11-0852-5.OCLC982478298.

{{cite book}}:CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^"anna dumont twitter".Twitter.Retrieved8 November2022.

- ^W.C.W.N. (20 February 1960)."Obituary: Dr Wu Lien-Teh".The Lancet.Originally published as Volume 1, Issue 7121.275(7121): 444.doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(60)90379-2.ISSN0140-6736.

- ^abCooray, Francis; Nasution Khoo Salma.Redoutable Reformer: The Life and Times of Cheah Cheang Lim.Areca Books, 2015.ISBN9789675719202

- ^"The Chinese Doctor Who Beat the Plague".China Channel.20 December 2018.Retrieved10 March2021.

- ^ab"Obituary: WU LIEN-TEH, M.D., Sc.D., Litt.D., LL.D., M.P.H".Br Med J.1(5170): 429–430. 6 February 1960.doi:10.1136/bmj.1.5170.429-f.ISSN0007-1447.PMC1966655.

- ^Flohr, Carsten (1996). "The Plague Fighter: Wu Lien-teh and the beginning of the Chinese public health system".Annals of Science.53(4): 361–380.doi:10.1080/00033799608560822.ISSN0003-3790.PMID11613294.

- ^abcMa, Zhongliang; Li, Yanli (2016)."Dr. Wu Lien Teh, plague fighter and father of the Chinese public health system".Protein & Cell.7(3): 157–158.doi:10.1007/s13238-015-0238-1.ISSN1674-800X.PMC4791421.PMID26825808.

- ^abcdWilson, Mark (24 March 2020)."The untold origin story of the N95 mask".Fast Company.Retrieved26 March2020.

- ^Wu Lien-te; World Health Organization (1926).A Treatise on Pneumonic Plague.Berger-Levrault.

- ^Lynteris, Christos (18 August 2018)."Plague Masks: The Visual Emergence of Anti-Epidemic Personal Protection Equipment".Medical Anthropology.37(6): 442–457.doi:10.1080/01459740.2017.1423072.hdl:10023/16472.ISSN0145-9740.PMID30427733.

- ^Mates, Lewis H. (29 April 2016).Encyclopedia of Cremation.Routledge. pp. 300–301.ISBN978-1-317-14383-3.

- ^abSummers, William C. (11 December 2012).The Great Manchurian Plague of 1910-1911: The Geopolitics of an Epidemic Disease.Yale University Press.ISBN978-0-300-18476-1.

- ^"Inaugural address delivered at the opening of the International Plague Conference, Mukden, April 4th, 1911".Wellcome Collection.1911.Retrieved26 March2020.

- ^Lynteris, Christos (1 September 2013). "Skilled Natives, Inept Coolies: Marmot Hunting and the Great Manchurian Pneumonic Plague (1910–1911)".History and Anthropology.24(3): 303–321.doi:10.1080/02757206.2012.697063.ISSN0275-7206.S2CID145299676.

- ^Courtney, Chris (2018),"The Nature of Disaster in China: The 1931 Central China Flood",Cambridge University Press [ISBN978-1-108-41777-8]

- ^Article in Chinese."Picture of" Taman Wu Lien Teh "".Archived fromthe originalon 27 August 2011.Retrieved1 June2011.

- ^"The Dr. Wu Lien-Teh Society, Penang tân thành ngũ liên đức học hội | Celebrating the life of the man who brought modern medicine to China, who fought the Manchurian plague, and who set the standard for generations of doctors to follow. Ngũ liên đức bác sĩ: Đấu dịch phòng trị, thôi tiến y học, ca tụng quốc sĩ vô song".Retrieved26 March2020.

- ^abWai, Wong Chun (11 February 2020)."Wu Lien-Teh: Malaysia's little-known plague virus fighter".The Star Online.Retrieved26 March2020.

- ^Wu, Yu-lin (1995).Memories of Dr. Wu Lien-teh, Plague Fighter.World Scientific.ISBN978-981-02-2287-1.

- ^Wang, Helena Hui; Lau, Esther; Horton, Richard; Jiang, Baoguo (6 July 2019)."The Wakley–Wu Lien Teh Prize Essay 2019: telling the stories of Chinese doctors".The Lancet.394(10192): 11.doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31517-X.ISSN0140-6736.PMID31282345.S2CID205990913.

- ^Article in Chinese."130th memorial of Dr. Wu Lien-the".Archived fromthe originalon 24 March 2012.Retrieved1 June2011.

- ^Toh, Han Shih (1 February 2020)."Lessons from Chinese Malaysian plague fighter for Wuhan virus".South China Morning Post.Retrieved26 March2020.

- ^"Home".DrYvonneHo.com.

- ^"Home".DrWuLienTeh.com.

- ^Liu, Ling Woo (18 July 2020)."The Good Doctor".South China Morning Post.Retrieved25 July2020.

- ^Ho, Yvonne (30 August 2020)."The Good Doctor from Penang".The Star.Retrieved6 September2020.

- ^Musil, Steven (9 March 2021)."Google Doodle celebrates Dr. Wu Lien-teh, surgical mask pioneer".CNET.Archivedfrom the original on 12 March 2021.Retrieved12 March2021.

- ^Sam Wong (10 March 2021)."Dr Wu Lien-teh: Face mask pioneer who helped defeat a plague epidemic".New Scientist.Archivedfrom the original on 12 March 2021.Retrieved12 March2021.

- ^Phoebe Zhang (11 March 2021)."Google honours Chinese-Malaysian face mask pioneer Doctor Wu Lien-teh, whose surgical face covering is seen as origin of N95".South China Morning Post.Archivedfrom the original on 12 March 2021.Retrieved12 March2021.

Further reading

[edit]- Wu Lien-Teh, 1959.Plague Fighter: The Autobiography of a Modern Chinese Physician.Cambridge. (Reprint: Areca Books. 2014ISBN978-967-5719-14-1)

- Yang, S. 1988. "Dr. Wu Lien-teh and the national maritime quarantine service of China in 1930s". Zhonghua Yi Shi Za Zhi 18:29–32.

- Wu Yu-Lin. 1995.Memories of Dr. Wu Lien-Teh: Plague Fighter.World Scientific Pub Co Inc.ISBN981-02-2287-4

- Flohr, Carsten. 1996. "The plague fighter: Wu Lien-teh and the beginning of the Chinese public health system".Annals of Science53:361–80

- Gamsa, Mark. 2006."The Epidemic of Pneumonic Plague in Manchuria 1910–1911".Past & Present190:147–183

- Lewis H. Mates, ‘Lien-Teh, Wu’, in Douglas Davies with Lewis H. Mates (eds),Encyclopedia of Cremation(Ashgate, 2005): 300–301.Lien-Teh, Wu

- Penang Free School archivePFS Online

External links

[edit]- 1879 births

- 1960 deaths

- Alumni of Emmanuel College, Cambridge

- Chinese infectious disease physicians

- Qing dynasty government officials

- League of Nations people

- Malaysian people of Cantonese descent

- People from Penang

- Malaysian people of Hakka descent

- People from Singapore

- Malaysian people of Chinese descent

- Queen's Scholars (British Malaya and Singapore)

- Peranakan people in Malaysia

- Physicians of St Mary's Hospital, London

- Malaysian public health doctors

- 20th-century Chinese physicians