Xenocyon

| Xenocyon Temporal range:Plioceneto MiddlePleistocene

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Canis(Xenocyon)falconeriskull | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Carnivora |

| Family: | Canidae |

| Genus: | Canis |

| Subgenus: | †Xenocyon Kretzoi,1938[1] |

| Species | |

Parts of this article (those related to systematics concerning recent specieshttps://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2015.06.060) need to beupdated.(February 2023) |

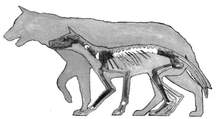

Xenocyon( "strange dog" ) is an extinct group of canids, either considered a distinctgenus[2]or asubgenusofCanis.The group includesCanis(Xenocyon)africanus,Canis(Xenocyon)antoniiandCanis(Xenocyon)falconerithat gave rise toCanis(Xenocyon)lycanoides.[3]ThehypercarnivorousXenocyonis thought to be closely related and possibly ancestral to moderndholeand theAfrican wild dog,[4]: p149 as well as the insularSardinian dhole.[5]

Taxonomy[edit]

Xenocyonis proposed as a subgenus ofCanisnamedCanis(Xenocyon).[3]Onetaxonomicauthority proposes that as part of this subgenus, the group namedCanis(Xenocyon) ex gr.falconeri(ex gr. meaning "of the group including" ) would include all of the large hypercarnivorous canids that inhabited theOld Worldduring the Late Pliocene–Early Pleistocene:Canis(Xenocyon)africanusinAfrica,Canis(Xenocyon)antoniiinAsiaandCanis(Xenocyon)falconeriinEurope.Further, these three could be regarded as extreme geographical variations within the onetaxon.This group was hypercanivorous, had a large body size that is comparable with the northern populations of the moderngray wolf(Canis lupus) and are characterized by a shortneurocraniumrelative to their skull size.[3]

The ancestral condition for canids is to have five toes on their forelimbs, but by theEarly Pleistocenethis lineage had reduced this to four, which is also a characteristic feature of the modernAfrican wild dog(Lycaon pictus).[6][7]The African wild dog cannot be positively identified in thefossil recordof eastern Africa until the middle Pleistocene,[8]and identifying the oldestLycaonfossil is difficult because these are hard to distinguish fromCanis(Xenocyon)africanus.[7]Some authors considerCanis(Xenocyon)lycanoidesas ancestral to the generaLycaonandCuon.[9][10][11][4]: p149 Therefore, one taxonomic authority has proposed that all of theCanis(Xenocyon) group should be reclassified into the genusLycaon.This would form threechronospecies:Lycaon falconeriduring theLate Plioceneof Eurasia,Lycaon lycaonoidesduring the Early Middle Pleistocene of Eurasia and Africa andLycaon pictusfrom the Middle Late Pleistocene to present.[6]

Species[edit]

Canis(Xenocyon)africanus[edit]

The species was originally namedCanis africanus(Pohle 1928)[12]but was later reassigned asCanis(Xenocyon)africanus.It existed during theLate PlioceneandEarly Pleistoceneof Africa.[3]

Canis(Xenocyon)antonii[edit]

The species was originally namedCanis antonii(Zdansky 1924)[13]but was later reassigned asCanis(Xenocyon)antonii.It existed during the late Pliocene and Early Pleistocene of Asia.[3]The name was applied to Late Pliocene fossils of canids with hypercarnivorous dentition that were found in China at the sites Loc. 33 (Yangshao,Henan), Loc. 64 (ZhiliProvince) andFancun,ShanxiProvince.[14]The species was recorded in Europe asCanis(Xenocyon)falconeri.[6]

Canis(Xenocyon)falconeri[edit]

UpperValdarnois the name given to that part of theArnovalley situated in the provinces ofFlorenceandArezzo,Italy. The region is bounded by thePratomagnomountain range to the north and east and by the Chianti mountains to the south and west. The Upper Valdarno Basin has provided the remains of three fossil canid species dated to the LateVillafranchianera of Europe 1.9-1.8 million years ago that arrived with a faunal turnover around that time (Early Pleistocene). It is here that the Swiss paleontologistCharles Immanuel Forsyth Majordiscovered Falconer's wolf (Canis falconeri) (Forsyth Major 1877).[15]The species was later reassigned asCanis(Xenocyon)falconeri,[3]but was later regarded as the European arrival ofCanis(Xenocyon)antonii.[6]The species gave rise toCanis(Xenocyon)lycanoides.[3]

Canis(Xenocyon)lycaonoides[edit]

The species was originally namedXenocyon lycaonoides(Kretzoi 1938)[1]but was later reassigned asCanis(Xenocyon)lycanoides.[3]

Another view is thatlycaonoidesandfalconerishould be classified under genusLycaon,to give the descent of 3 chronospecies:L. falconeriLate Pliocene of Eurasia →L. lycaonoidesEarly Pleistocene and the beginning of theMiddle Pleistoceneof Eurasia and Africa →L. pictusMiddle Pleistocene to the present day.[6]

The diversity of the wolf-sized species decreased by the end of the Early Pleistocene and into the Middle Pleistocene of Europe and Asia. These wolves include the large hypercarnivorousCanis(Xenocyon)lycaonoidesthat was comparable in size with the modern gray wolf (C. lupus) northern populations and the small Mosbach wolf (C. mosbachensis) that is comparable in size to the modernIndian wolf(C. l. pallipes). Both types of wolves could be found existing from England and Greece across Europe to the high latitudes of Siberia through to Transbaikalia, Tajikistan, Mongolia, and China.[14]Remains of both canid species are also found inUbeidiya,in the southern Levant.[16]The true gray wolves did not make an appearance until the end of the Middle Pleistocene, 500-300 thousand years ago.[14]

Fossil evidence to dated 1.8 million years ago fromDmanisi,Georgia in the southern Caucasus suggests that they were cooperative hunters which cared for their sick, injured and disabled pack members similar to the modern grey wolf.[17]

It preyed onantelope,deer,elephantcalves,aurochs,baboons,wild horsesand possiblyhumans.It was probably the ancestor of theAfrican wild dog(Lycaon pictus) and possibly thedhole(Cuon alpinus) of southeastern Asia, the extinctSardinian dhole(Cynotherium sardous)[6][18][9]and perhaps two extinct Javanese dogs (Merriam's dog (Megacyon merriami) and the Trinil dog (Mececyon trinilensis)).[19][20]

Just before the appearance of thedire wolf(Aenocyon dirus), North America was invaded by the genusXenocyon,which was as large asA. dirusand more hypercarnivorous. The fossil record shows them as rare and it is assumed that they could not compete with the newly derivedA. dirus.[4]These have been ascribed toXenocyon lycaonoides,withXenocyon texanusfrom as far south as Texas as itstaxonomic synonym.[21]

References[edit]

- ^abKretzoi, M. 1938. Die Raubtiere von Gombaszög nebst einer Übersicht der Gesamtfauna. Annales Museum Nationale Hungaricum 31: 89–157.

- ^Jiangzuo, Qigao; Wang, Yuan; Song, Yayun; Liu, Sizhao; Jin, Changzhu; Liu, Jinyi (2022-01-06). "Middle Pleistocene Xenocyon lycaonoides Kretzoi, 1938 in northeastern China and the evolution of Xenocyon-Lycaon lineage".Historical Biology:1–13.doi:10.1080/08912963.2021.2022138.ISSN0891-2963.

- ^abcdefghRook, L. 1994. The Plio-Pleistocene Old World Canis (Xenocyon) ex gr. falconeri. Bolletino della Società Paleontologica Italiana 33:71–82.

- ^abcWang, Xiaoming; Tedford, Richard H.; Dogs: Their Fossil Relatives and Evolutionary History. New York: Columbia University Press, 2008.

- ^Madurell-Malapeira, Joan; Palombo, Maria Rita; Sotnikova, Marina (2015-07-04). "Cynotherium malatestai, sp. nov. (Carnivora, Canidae) from the early middle Pleistocene deposits of Grotta dei Fiori (Sardinia, Western Mediterranean)".Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology.35(4): e943400.Bibcode:2015JVPal..35E3400M.doi:10.1080/02724634.2014.943400.ISSN0272-4634.S2CID129741290.

- ^abcdefMartínez-Navarro, B. & L. Rook (2003). "Gradual evolution in the African hunting dog lineage: systematic implications".Comptes Rendus Palevol.2(#8): 695–702.Bibcode:2003CRPal...2..695M.doi:10.1016/j.crpv.2003.06.002.

- ^abCreel, Scott; Creel, Nancy Marusha (2002).The African Wild Dog: Behavior, Ecology, and Conservation.Princeton University Press, New Jersey. p. 3.ISBN978-0-691-01655-9.

- ^Werdelin, L.; Lewis, M.E. (2005)."Plio-Pleistocene Carnivora of eastern Africa: species richness and turnover patterns".Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society.144(#2): 121–144.doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.2005.00165.x.

- ^abMoulle, P.E.; Echassoux, A.; Lacombat, F. (2006)."Taxonomie du grand canidé de la grotte du Vallonnet (Roquebrune-Cap-Martin, Alpes-Maritimes, France)".L'Anthropologie.110(#5): 832–836.doi:10.1016/j.anthro.2006.10.001.Retrieved2008-04-28.(in French)

- ^Baryshnikov, Gennady F. "Pleistocene Canidae (Mammalia, Carnivora) from the Paleolithic Kudaro caves in the Caucasus." Russian Journal of Theriology 11.2 (2012): 77-120.

- ^Cherin, Marco; Bertè, Davide F.; Rook, Lorenzo; Sardella, Raffaele (2013). "Re-Defining Canis etruscus (Canidae, Mammalia): A New Look into the Evolutionary History of Early Pleistocene Dogs Resulting from the Outstanding Fossil Record from Pantalla (Italy)".Journal of Mammalian Evolution.21:95–110.doi:10.1007/s10914-013-9227-4.S2CID17083040.

- ^Pohle H., 1928. Die Raubtiere von Oldoway. Wissenschaftliche Ergebnisse der Oldoway-Expedition 1913 (N F) 3: 45–54.

- ^O. Zdansky, Jungtertiäre Carnivoren Chinas, Paleontol. Sin., ser. C II (1) (1924) 38–45.

- ^abcSotnikova, M (2010). "Dispersal of the Canini (Mammalia, Canidae: Caninae) across Eurasia during the Late Miocene to Early Pleistocene".Quaternary International.212(#2): 86–97.Bibcode:2010QuInt.212...86S.doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2009.06.008.

- ^Forsyth Major CI (1877) Considerazioni sulla fauna dei Mammiferi pliocenici e postpliocenici della Toscana. III. Cani fossili del Val d’Arno superiore e della Valle dell’Era. Mem Soc Tosc Sci Nat 3:207–227

- ^Martínez-Navarro, Bienvenido; Belmaker, Miriam; Bar-Yosef, Ofer (May 2009)."The large carnivores from 'Ubeidiya (early Pleistocene, Israel): biochronological and biogeographical implications".Journal of Human Evolution.56(5): 514–524.doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2009.02.004.Retrieved23 March2024– via Elsevier Science Direct.

- ^Bartolini-Lucenti, Saverio; Madurell-Malapeira, Joan; Martínez-Navarro, Bienvenido; Palmqvist, Paul; Lordkipanidze, David; Rook, Lorenzo (2021)."The early hunting dog from Dmanisi with comments on the social behaviour in Canidae and hominins".Scientific Reports.11(1): 13501.Bibcode:2021NatSR..1113501B.doi:10.1038/s41598-021-92818-4.PMC8322302.PMID34326360.

- ^Lyras, G.A.; Van Der Geer, A.E.; Dermitzakis, M.; De Vos, J. (2006). "Cynotherium sardous,an insular canid (Mammalia: Carnivora) from the Pleistocene Of Sardinia (Italy), and its origin ".Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology.26(3): 735–745.doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2006)26[735:CSAICM]2.0.CO;2.S2CID84448363.

- ^Lyras, G.A.; Van Der Geer, A.E.; Rook, L. (2010). "Body size of insular carnivores: evidence from the fossil record".Journal of Biogeography.37(#6): 1007–1021.doi:10.1111/j.1365-2699.2010.02312.x.S2CID53700369.

- ^Van der Geer, A.; Lyras, G.; De Vos, J.; Dermitzakis M. (2010).Evolution of Island Mammals: adaptation and extinction of placental mammals on islands.Wiley-Blackwell (Oxford, UK).ISBN978-1-4051-9009-1.

- ^Tedford, Richard H.; Wang, Xiaoming; Taylor, Beryl E. (2009). "Phylogenetic Systematics of the North American Fossil Caninae (Carnivora: Canidae)".Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History.325:1–218.doi:10.1206/574.1.hdl:2246/5999.S2CID83594819.