Yangmingism

School of the Heart(Chinese:Tâm học;pinyin:xīn xué), orYangmingism(Chinese:Dương minh học;pinyin:yángmíng xué;Japanese:Dương minh học,romanized:yōmeigaku), is one of the major philosophical schools ofNeo-Confucianism,based on the ideas of theidealistNeo-Confucian philosopherWang Shouren(whose pseudonym was Yangming Zi and thus is often referred asWang Yangming). Throughout the wholeYuan dynasty,as well as in the beginning of theMing dynasty,the magistral philosophy in China was the Rationalistic School, anotherNeo-Confucianismschool emphasizing the importance of observational science built byCheng Yiand especiallyZhu Xi.[1]Wang Yangming, on the other hand, developed his philosophy as the main intellectual opposition to the Cheng-Zhu School. Yangmingism is considered to be part of the School of Mind established byLu Jiuyuan,upon whom Yangming drew inspirations. Yangming argued that one can learn thesupreme principle( lý, pinyin: Li) from their minds, objecting to Cheng and Zhu's belief that one can only seek the supreme principle in the objective world. Furthermore, Yangmingism posits a oneness of action and knowledge in relation to one's concepts of morality. This idea, "regard the inner knowledge and the exterior action as one" (Tri hành hợp nhất) is the main tenet in Yangmingism.[2]

It is sometimes called the Lu-Wang school by people who wish to emphasize the influence ofLu Jiuyuan.[3]Xinxue was seen as a rival to theLixueschool sometimes called theCheng-Zhu schoolafter its leading philosophers,Cheng YiandZhu Xi.[3]

Yangming's philosophy was inherited and spread by his disciples. Eventually, Yangmingism overtook the dominance of the Cheng-Zhu School and started to have followers outside China. Yangmingism became an influence on the incipientanti-foreignermovement in 19th century Japan.[4]In the 20th century, Japanese author and nationalistYukio Mishimaexamined Yangmingism as an integral part of the ideologies behind theMeiji Restorationas well as further samurai resistance, in particular theShinpūren rebellion.[5]

Some have described it as influential on theCultural Revolutionfor its idea of internal transformation.[6]

Origins[edit]

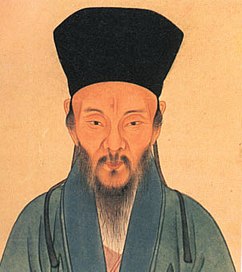

In 1472, Yangming was born in a rich household inYuyao,Zhejiang.Yangming's father ranked first place in theimperial examinationin 1481, thus he had been expecting his children to inherit his knowledge and start their career by participating in the imperial examination.[7]

When Yangming was 12 years old, Yangming's father sent him to a private school to prepare for the exam. At the age of eighteen, Yangming had a talk withLou Liang,who was one of the representative figures ofCheng-Zhu Schoolat that time. Lou's teachings had significantly enhanced Yangming's interest inCheng-Zhu School.After their conversations, Yangming managed to read through all ofZhu’s work, reflecting onCheng-Zhu School’s principle that “to acquire knowledge one must study things” (Cách vật trí tri). To practice this principle, Yangming spent seven days doing nothing except staring at, or so to say, studying the bamboos planted in the garden.[7]

Not surprisingly, not only did he not learn anything from the bamboos, but Yangming also fell seriously ill after sitting in the garden for seven days. Therefore, Yangming had given up on most of the Cheng-Zhu literature, as well as the idea of taking the imperial examination.[7]Instead, he began to read texts written by other Chinese philosophers, and eventually narrowed his focus onTaoismandLu Jiuyuan,whose work had been a major opponent to the Cheng-Zhu's Rationalistic School.[8]

Though Yangming had lost his faith in the imperial examination, he still signed up for the exam for the sake of his father. He passed the exam and was later assigned to work in the construction department in the central government. In 1506, Yangming was caught in political conflicts, and soon was demoted toGuizhou,the most deserted place in China at that time.[7]Yangming soon recovered from the setback. While working on improving the living situations of people in Guizhou, Yangming developed his own philosophical principles, which were then called Yangminism, based onThe Great LearningandLu's work.[8]

Yangmingism became hugely popular in Southern China, especially Jiangxi and Jiangnan (except Suzhou), but not Anhui and Fujian, and by the sixteenth century the Cheng-Zhu orthodox school even in the North could not ignore its basic philosophical claims. The Yangmingist belief that all men were equally capable of moral behaviour led them to advocate the formation ofjiangxuestudy communities and that participating in the state was not necessary, which in turn led to rise of theDonglin movement.Northern literati, more dependent on governmental routes to success than their Southern counterparts, were less receptive to Yangmingism.[9]

Major philosophy principles[edit]

"The Supreme Principle is Buried in One's Heart-Mind"[edit]

Yangming inheritsLu Jiuyuan's idea that everything one needs can be found in one's heart, opposing toCheng-Zhu's idea that one must learn from the external things.[10]This was promoted with the adage "The Supreme Principle is Buried in One's Mind" ( bất ly nhật dụng thường hành nội, trực đáo tiên thiên vị họa thời ).

Yangming argues that there are countless matters existing in the world, we can never get to study all of, or even most of them. However, when we are interacting with the world, we are using our consciousness to look, smell, and hear what is all around us. Thus, we can find the existence of the whole world in our minds. If we think deeper, we can even see the extensions of the world there. The recognition of extensions here doesn't mean that one can see the whole picture of Eiffel Tower even he has never been to Paris. What Yangming has been trying to prove is that, as we have a completed set of perceptions of the world in our minds, we have as well gotten a hold of the ultimate philosophy, the truth of the world, the supreme principles which have been guiding and teaching us through the ages.

Achieve the ultimate consciousness[edit]

In his book,Truyện tập lục,orInstructions for Practical Living and Other Neo-Confucian Writingsin English, Yangming writes that "there is nothing exists outside our minds, there is no supreme principle exists outside our hearts."[10]However, the problem here is that we let all kinds of selfish desires cover up the supreme principle, so we can't practice the principle well in our daily lives. Yangming uses an example in his book to demonstrate his idea: if we see a child fall into water well, we can't help but feel bad for the child. The feeling of bad here is an embodiment of the inherent supreme principle in our minds. But, if the child happens to be the son of one's biggest enemy, he may not feel bad for the child after all.[10]This is the situation in which the supreme principle is covered by selfish desires. If one can remove all selfish desires from one's heart, then he would achieve the ultimate consciousness, which is the final purpose pursued by many Chinese philosophers throughout centuries.

One thing worth noticing here is that, the ultimate consciousness is also in accordance withCheng-Zhu's "to acquire knowledge one must study things (Cách vật trí tri) "in a way. This means that one must conduct appropriate behaviors under certain circumstances. For instance, everyone knows they should care about their families' wellbeing. But if one only asks whether his families are feeling good or bad and does nothing when he receives the answer" feeling bad ", this cannot count as the ultimate consciousness. Only does one actually do things to take care of his families can be considered as knowing the ultimate consciousness.[10]

The unity of inner knowledge and action[edit]

The unity of inner knowledge and action, or "Tri hành hợp nhất",is probably the most important and well-known concept in Yangmingism. Yangming explains this concept as" Nobody can separate the knowledge and the action apart. If one knows, one will act. If one knows but don't act, then he has never actually known it. If you can obtain both, when you know something, you are already doing it; when you are doing something, then you already know it. "

"Nowadays, many people treat knowledge and actions as two distinct things. They think the need to know first, only then can they do something in this area. This lead them to do nothing, as well as to know nothing."

In other words,Tri hành hợp nhấtcould be interpret as the consistency of one's Supreme Principle and his objective actions. In the example of a child falling into water well, the action is not trying to save the child, but "feeling bad for the child". And the knowledge, the part of the Supreme Principle used here is the sympathy for others. For those who doesn't feel bad for the child, they haven't learn the knowledge of sympathy yet, thus they cannot apply the knowledge in their actions.

Similar ideas can be found in the western literature. InDemian,Hermann Hessewrites that "only the thoughts that we live out have any value."[11]MIT's motto "Mens et Manus,"[12]or "Mind and Hand," also reflect the importance of combining the inner knowledge and actions as one.

The Four-Sentence Teaching[edit]

In 1528, one year before his death, Yangming summaries his philosophies into a doctrine called "the Four-Sentence Teaching (Tứ cú giáo) ". The original Chinese text is"Vô thiện vô ác tâm chi thể, hữu thiện hữu ác ý chi động; tri thiện tri ác thị lương tri, vi thiện khứ ác thị cách vật".[13]which can be translated as "The Substance of the mind lacks good and lacks evil. When intentions are formed there is good and there is evil. 'Pure knowing' is knowing good and knowing evil. 'Getting a handle on things' is to do good and eliminate evil."

Education philosophies[edit]

Yangming regards education as the most efficient way to inspire people to find the Supreme Principle in their minds; it means that not only do education institutions need to teach students academic knowledge, but they also need to teach students moral and ethical principles.[14]He again emphasized the necessity ofuniting knowledge and actionsas one in the process of education.[10]Yangming believed that in order to achieve something, one must set up a specific goal first.[14]

Genres[edit]

Left philosophical genre[edit]

Zhezhong School[edit]

Notable figures in this genre include Nie Bao,Zou Shouyi,Xu Jie,andZhang Juzheng.Zhezhong School emphasizes on inner virtues. Scholars in this school regard virtues and knowledge are the foundation of one's life, arguing that one should solely focus on learning instead of actively seeking fames or reputations. They emphasize the importance of education.[8]

Right philosophical genre[edit]

Taizhou School[edit]

Notable figures include He Xinyin, Yan Shannong, andWang Gen.Taizhou School became widespread because it focuses on the general public. Scholars in Taizhou School believe that even the most ordinary person has the possibility of accomplishing extraordinary achievements. Everyone is a potential saint, as the universal truth is buried their own mind.[8]Taizhou School is rebellious against both the traditional and the Neo-Confucianism.

Critics[edit]

Chinese historian and philosopher,Wang Fuzhi,criticized that Yangming is more of aBuddhismfollower than aNeo-Confucianismphilosopher. Yangming's excessive concentration on minds had made his teaching contain a negative attitude coming from his early education inBuddhism.Fuzhi didn't agree with Yangming that there is no good or bad exist in both the world and people's minds. He also argued that tri hành hợp nhất, the unity of inner knowledge and actions had made people can no longer separate theories and actual matter apart.

In Japan[edit]

Dương minh học,orようめいがく,is the branch of Yangmingism in Japan. Yangmingism was spread to Japan in the later periods of the Ming Dynasty by a traveling Japanese monk. From 1568 to 1603, Yangmingism was at its preliminary stage in Japan. Later, whenthe Ming Dynastyended, some of the Ming scholars fled to Japan and helped to develop Yangmingism there.[15]In 1789, Yangmingism became an influential philosophy among the Japanese. Yangmingism had also played an essential role to Japan'sMeiji Restoration.[16]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^Chan, Wing-Tsit, ed. (1969).A source book in Chinese philosophy(New Impression ed.). New Jersey: Princeton University Press.ISBN978-1-4008-2003-0.OCLC859961526.

- ^"Vương thủ nhân: Thủy sang" tri hành hợp nhất "".2013-06-25. Archived fromthe originalon 2013-06-25.Retrieved2020-01-31.

- ^ab"Xinxue | Chinese philosophy | Britannica".

- ^Ravina, Mark (2004).The last samurai: the life and battles of Saigō Takamori.Hoboken, N.J.: John Wiley & Sons.ISBN0-471-08970-2.OCLC51898842.

- ^곽형덕 (2007)."Ma Hae-song and his involvement with Bungei-shunju and Modern-nihon".Journal of Korean Modern Literature(33): 5–34.doi:10.35419/kmlit.2007..33.001.ISSN1229-9030.

- ^Theobald, Ulrich."The School of the Human Mind tâm học (www.chinaknowledge.de)".www.chinaknowledge.de.Retrieved2023-04-07.

- ^abcdGuan Xiu, Zhang Tingzhong.History of Ming.

- ^abcdMinh nho học án.

- ^Chang Woei Ong (2020).Li Mengyang, the North-South Divide, and Literati Learning in Ming China.BRILL. pp. 67–69, 277, 288–289.ISBN978-1684170883.

- ^abcdeWang, Shouren.Truyện tập lục.

- ^Hesse, Hermann. (2019).Demian.Dreamscape Media.ISBN978-1-9749-3912-1.OCLC1080083089.

- ^"Mind and hand".MIT Admissions.3 February 2006.Retrieved2020-02-14.

- ^"Vương dương minh “Tứ cú giáo” chi: Tri thiện tri ác thị lương tri. "(in Chinese (Taiwan)).Retrieved2020-02-14.

- ^ab"Ngô quang: Vương dương minh giáo dục tư tưởng nội hàm thâm khắc ngũ điểm khải kỳ trị đắc tư khảo 【 đồ 】-- quý châu tần đạo -- nhân dân võng".gz.people.com.cn.Retrieved2020-02-14.

- ^"《 nhật bổn dương minh học đích thật tiễn tinh thần 》: Huýnh dị vu trung quốc đích nhật bổn dương minh học – quốc học võng"(in Chinese (China)).Retrieved2020-02-14.

- ^"Dương minh học đích hiện đại khải kỳ lục —— tiêu điểm chuyên đề".www.ebusinessreview.cn.Retrieved2020-02-14.