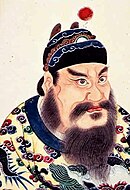

Qin Shi Huang

| Qin Shi Huang Tần thủy hoàng | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||

| Emperor of the Qin dynasty | |||||||||

| Reign | 221 – 210 BC[b] | ||||||||

| Successor | Qin Er Shi | ||||||||

| King of Qin | |||||||||

| Reign | 6 July 247 BC[c]– 221 BC | ||||||||

| Predecessor | King Zhuangxiang | ||||||||

| Successor | Position abolished Himself as Emperor | ||||||||

| Born | Ying Zheng (Doanh chính) or Zhao Zheng (Triệu chính) February 259 BC[d] Handan,state of Zhao | ||||||||

| Died | 12 July 210 BC (aged 49) Shaqiu,Qin dynasty | ||||||||

| Burial | |||||||||

| Issue | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| House | Ying | ||||||||

| Dynasty | Qin | ||||||||

| Father | King Zhuangxiang | ||||||||

| Mother | Queen Dowager Zhao | ||||||||

Qin Shi Huang(Chinese:Tần thủy hoàng,;February 259[e]– 12 July 210 BC) was the founder of theQin dynastyand the firstemperor of China.[9]Rather than maintain the title of "king"(wángVương) borne by the previousShangandZhourulers, he assumed the invented title of "emperor" (huángdìHoàng đế), which would see continuous use by monarchs in China for the next two millennia.

Born in Handan, the capital ofZhao,asYing Zheng(Doanh chính) orZhao Zheng(Triệu chính), his parents wereKing Zhuangxiang of QinandLady Zhao.The wealthy merchantLü Buweiassisted him in succeeding his father asthe king of Qin,after which he becameKing Zheng of Qin.By 221 BC, he had conquered all the other warring states andunified all of China,and he ascended the throne as China's first emperor. During his reign, his generals greatly expanded the size of the Chinese state:campaignssouth ofChupermanently added theYuelands ofHunanandGuangdongto theSinosphere,andcampaignsinInner Asiaconquered theOrdos Plateaufrom the nomadicXiongnu,although the Xiongnu later rallied underModu Chanyu.

Qin Shi Huang also worked with his ministerLi Sito enact major economic and political reforms aimed at the standardization of the diverse practices amongearlier Chinese states.He is traditionally said to havebanned and burned many books and executed scholars.His public works projects included the incorporation of diverse state walls into a singleGreat Wall of Chinaand a massive new national road system, as well as his city-sizedmausoleumguarded by a life-sizedTerracotta Army.He ruled until his death in 210 BC, during hisfifth tour of eastern China.[10]

Qin Shi Huang has often been portrayed as a tyrant and strictLegalist—characterizations that stem partly from the scathing assessments made during theHan dynastythat succeeded the Qin. Since the mid-20th century, scholars have begun questioning this evaluation, inciting considerable discussion on the actual nature of his policies and reforms. According to the sinologistMichael Loewe"few would contest the view that the achievements of his reign have exercised a paramount influence on the whole of China's subsequent history, marking the start of an epoch that closed in 1911".[11]

Names

| Qin Shi Huang | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

"Qin Shi Huang" inseal script(top) andregular script(bottom) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese | Tần thủy hoàng | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | "First Emperor ofQin" | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Regnal name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese | Thủy hoàng đế | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | "First Emperor" | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Modern Chinese sources often give the personal name of Qin Shi Huang as Ying Zheng, withYíng(Doanh) taken as the surname and Zheng (Chính) the given name. However, in ancient China, the naming convention differed, and the clan nameZhao(Triệu), the place where he was born and raised, may be used as the surname. Unlike modernChinese names,the nobility of ancient China had two distinct surnames: theancestral name(Tính) comprised a larger group descended from aprominent ancestor,usually said to have lived during the time of the legendaryThree Sovereigns and Five Emperors,and the clan name (Thị) comprised a smaller group that showed a branch's current fief or recent title. The ancient practice was to list men's names separately—Sima Qian's "Basic Annals of the First Emperor of Qin" introduces him as "given the name Zheng and the surnameZhao"[12][f]—or to combine the clan surname with the personal name: Sima's account ofChudescribes the sixteenth year of the reign ofKing Kaolieas "the time when Zhao Zheng was enthroned as King of Qin".[14]However, since modern Chinese surnames (despite usually descending from clan names) use the same character as the oldancestralnames, it is much more common in modern Chinese sources to see the emperor's personal name written as Ying Zheng,[g]using the ancestral name of theHouse of Ying.

The rulers of thestate of Qinhad styled themselveskingsfrom the time ofKing Huiwenin 325 BC. Upon his ascension, Zheng became known as the King of Qin[12][13]or King Zheng of Qin.[15][16]This title made him the nominal equal of the rulers ofShangandZhou,thelast of whose kingshad been deposed byKing Zhaoxiang of Qinin 256 BC.

Following the surrender ofQiin 221 BC, King Zheng reunited all of the lands of the formerKingdom of Zhou.Rather than maintain his rank as king, however,[17]he created a new title ofhuángdì(emperor) for himself. This new title combined two titles—huángof the mythical Three Sovereigns (Tam hoàng,Sān huáng) and thedìof the legendaryFive Emperors(Ngũ đế,Wŭ Dì) ofChinese prehistory.[18]The title was intended to appropriate some of the prestige of theYellow Emperor,[19]whose cult was popular in the laterWarring States periodand who was considered to be a founder of the Chinese people. King Zheng chose the newregnal nameof First Emperor (Shǐ Huángdì,Wade-GilesShih Huang-ti)[20]on the understanding that his successors would be successively titled the "Second Emperor", "Third Emperor", and so on through the generations. (In fact, the scheme lasted only as long as his immediate heir, theSecond Emperor.)[21]The new title carried religious overtones. For that reason,sinologistsstarting withPeter A. Boodberg[citation needed]orEdward H. Schafer[22]—sometimes translate it as "thearch" and the First Emperor as the First Thearch.[23]

The First Emperor intended that his realm would remain intact through the ages but, following its overthrow and replacement byHanafter his death, it became customary to prefix his title with Qin. Thus:

- Tần,Qínor Ch'in, "of Qin"

- Thủy,Shǐor Shih, "first"[24]

- Hoàng đế,Huángdìor Huang-ti, "emperor", a new term[h]coined from

- Hoàng,Huángor Huang, literally "shining" or "splendid" and formerly most usually applied "as an epithet of Heaven",[26]a title of theThree Sovereigns,the high god of the Zhou[25]

- Đế,Dìor Ti, the high god of theShang dynasty,possibly composed of theirdivine ancestors,[27]and used by the Zhou as a title of the legendaryFive Emperors,particularly theYellow Emperor

As early as Sima Qian, it was common to shorten the resulting four-character Qin Shi Huangdi toTần thủy hoàng,[28]variously transcribed as Qin Shihuang or Qin Shi Huang.

Following his elevation as emperor, both Zheng's personal nameChínhand possibly its homophoneChính[i]becametaboo.[j]The First Emperor also arrogated the first-person pronounTrẫmfor his exclusive use, and in 212 BC began calling himself The Immortal(Chân nhân,Others were to address him as "Your Majesty"(Bệ hạ,in person and "Your Highness" (Thượng) in writing.[17]

Birth and parentage

According to theShijiwritten bySima Qianduring the Han dynasty, the first emperor was the eldest son of the Qin prince Yiren, who later becameKing Zhuangxiang of Qin.Prince Yiren at that time was residing at the court ofZhao,serving as a hostage to guarantee the armistice between Qin and Zhao.[24][30]Prince Yiren had fallen in love at first sight with aconcubineofLü Buwei,a rich merchant from thestate of Wey.Lü consented for her to be Yiren's wife, who then became known asLady Zhaoafter the state of Zhao. He was given the name Zhao Zheng, the name Zheng (Chính) came from his month of birthZhengyue,the first month of theChinese lunar calendar;[30]the clan name ofZhaocame from his father's lineage and was unrelated to either his mother's name or the location of his birth.[citation needed](Song Zhongsays that his birthday, significantly, was on the first day ofZhengyue.[31]) Lü Buwei's machinations later helped Yiren becomeKing Zhuangxiang of Qin[32]in 250 BC.

However, theShijialso claimed that the first emperor was not the actual son of Prince Yiren but that of Lü Buwei.[33]According to this account, when Lü Buwei introduced the dancing girl to the prince, she was Lü Buwei'sconcubineand had already become pregnant by him, and the baby was born after an unusually long period of pregnancy.[33]According to translations of theLüshi Chunqiu,Zhao Ji gave birth to the future emperor in the city ofHandanin 259 BC, the first month of the 48th year ofKing Zhaoxiang of Qin.[34]

The idea that the emperor was an illegitimate child, widely believed throughout Chinese history, contributed to the generally negative view of the First Emperor.[24]However, a number of modern scholars have doubted this account of his birth. SinologistDerk Boddewrote: "There is good reason for believing that the sentence describing this unusual pregnancy is an interpolation added to theShijiby an unknown person in order to slander the First Emperor and indicate his political as well as natal illegitimacy ".[35]John Knoblock and Jeffrey Riegel, in their translation of Lü Buwei'sLüshi Chunqiu,call the story "patently false, meant both to libel Lü and to cast aspersions on the First Emperor".[36]Claiming Lü Buwei—a merchant—as the First Emperor's biological father was meant to be especially disparaging, since later Confucian society regarded merchants as thelowest social class.[37]

Reign as King of Qin

Regency

In 246 BC, whenKing Zhuangxiangdied after a short reign of just three years, he was succeeded on the throne by his 13-year-old son.[38]At the time, Zhao Zheng was still young, so Lü Buwei acted as the regent prime minister of the State of Qin, which was still waging war against theother six states.[24]Nine years later, in 235 BC, Zhao Zheng assumed full power after Lü Buwei was banished for his involvement in a scandal with Queen Dowager Zhao.[39]

Zhao Chengjiao,the Lord Chang'an (Trường an quân),[40]was Zhao Zheng's legitimate half-brother, by the same father but from a different mother. After Zhao Zheng inherited the throne, Chengjiao rebelled atTunliuand surrendered to the state of Zhao. Chengjiao's remaining retainers and families were executed by Zhao Zheng.[41]

Lao Ai's attempted coup

As King Zheng grew older, Lü Buwei became fearful that the boy king would discover his liaison with his mother,Lady Zhao.He decided to distance himself and look for a replacement for the queen dowager. He found a man namedLao Ai.[42]According toThe Record of Grand Historian,Lao Ai was disguised as a eunuch by plucking his beard. Later Lao Ai and queen Zhao Ji got along so well that they secretly had two sons together.[42]Lao Ai was ennobled as Marquis, and was showered with riches. Lao Ai had been planning to replace King Zheng with one of his own sons, but during a dinner party he was heard bragging about being the young king's stepfather.[42]In 238 BC, while the king was travelling to the former capital, Yong (Ung), Lao Ai seized the queen mother'ssealand mobilized an army in a coup attempt.[42]When notified of the rebellion, King Zheng ordered Lü Buwei to letLord ChangpingandLord Changwenattack Lao Ai. Although the royal army killed hundreds of rebels at the capital, Lao Ai successfully fled the battlefield.[43]

A price of 1 million copper coins was placed on Lao Ai's head if he was taken alive or half a million if dead.[42]Lao Ai's supporters were captured and beheaded; then Lao Ai was tied up and torn to five pieces by horse carriages, while his entire family was executed to the third degree.[42]The two hidden sons were also killed, while the mother Zhao Ji was placed under house arrest until her death many years later. Lü Buwei drank a cup of poisoned wine and committed suicide in 235 BC.[24][42]Ying Zheng then assumed full power as the King of the Qin state. Replacing Lü Buwei,Li Sibecame the newchancellor.

First assassination attempt

King Zheng and his troops continued their conquest of the neighbouring states. Thestate of Yanwas no match for the Qin states: small and weak, it had already been harassed frequently by Qin soldiers.[10]Crown Prince Dan of Yanplotted an assassination attempt against King Zheng, recruitingJing KeandQin Wuyangfor the mission in 227 BC.[32][10]

The assassins gained access to King Zheng by pretending a diplomatic gifting of goodwill: a map of Dukang and the severed head ofFan Wuji.[10]Qin Wuyang stepped forward first to present the map case but was overcome by fear. Jing Ke then advanced with both gifts, while explaining that his partner was trembling because "[he] had never set eyes on theSon of Heaven".When the dagger unrolled from the map, the king leapt to his feet and struggled to draw his sword – none of his courtiers was allowed to carry arms in his presence. Jing stabbed at the king but missed, and King Zheng slashed Jing's thigh. In desperation, Jing Ke threw the dagger but missed again. He surrendered after a brief fight in which he was further injured. The Yan state was conquered in its entirety five years later.

Second assassination attempt

Gao Jianliwas a close friend of Jing Ke, and wanted to avenge his death.[44]As a famousluteplayer, he was summoned to play for King Zheng. Someone in the palace recognized him and guessed his plans.[45]Reluctant to kill such a skilled musician, the emperor ordered his eyes put out, and then proceeded with the performance. The king praised Gao's playing and even allowed him closer. The lute had been weighted with a slab of lead, and Gao Jianli swung it at the king but missed. The second assassination attempt had failed; Gao was executed shortly after.

Unification of China

In 230 BC, King Zheng began the final campaigns of theWarring States period,setting out to conquer the remaining six major Chinese states and bring China under unified Qin control.

The state ofHan,the weakest of the Warring States, was the first to fall in 230 BC. In 229, Qin armies invadedZhao,which had been severely weakened by natural disasters, and captured the capital ofHandanin 228. PrinceJia of Zhaomanaged to escape with the remnants of the Zhao army and established the short-lived state ofDai,proclaiming himself king.

In 227 BC, fearing a Qin invasion,Crown Prince DanofYanordered afailed assassination attempton King Zheng. This providedcasus bellifor Zheng to invade Yan in 226, capturing the capital ofJi(modernBeijing) that same year. The remnants of the Yan army, along with KingXi of Yan,were able to retreat to theLiaodong Peninsula.

After Qin besieged and flooded their capital ofDaliang,thestate of Weisurrendered in 225 BC. Around this time, as a precautionary measure, Qin seized ten cities from Chu, the largest and most powerful of the other Warring States. In 224, Qin launched a full-scale invasion of Chu, capturing the capital of Shouchun in 223. In 222, Qin armies extinguished the last Yan remnants in Liaodong and the Zhao rump state of Dai. In 221, Qin armies invaded the state ofQiand captured KingJian of Qiwithout much resistance, bringing an end to theWarring States period.

By 221 BC, all Chinese lands had been unified under the Qin. To elevate himself above the feudal Zhou kings, King Zheng proclaimed himself the First Emperor, creating the title which would be used as the title of the Chinese sovereign for the next two millennia. Qin Shi Huang also ordered theHeshibito be crafted into theHeirloom Seal of the Realm,which would serve as a physical symbol of theMandate of Heaven,and would be passed from emperor to emperor until its loss in the 10th century.

During 215 BC, in an attempt to expand Qin territory, Qin Shi Huang orderedmilitary campaigns against the Xiongnu nomadsin the North. Led by GeneralMeng Tian,Qin armies successfully routed the Xiongnu from theOrdos Plateau,setting the ancient foundations for the construction of theGreat Wall of China.In the South, Qin Shi Huang also ordered severalmilitary campaigns against the Yue tribes,which annexed various regions in modernGuangdongand Vietnam.[46]

Reign as Emperor of Qin

Administrative reforms

In an attempt to avoid a recurrence of the political chaos of theWarring States period,Qin Shi Huang and Li Si worked to completely abolish the feudal system of loose alliances and federations.[47][46]They organized the empire into administrative units and subunits: first 36 (later 40)commanderies,thencounties,townships, and hundred-family units ( lí,Li,roughly corresponding to modern-daysubdistrictsandcommunities).[48]People assigned to these units would no longer be identified by their native region or former feudal state, for example "Chu person" ( sở nhân,Chu rén).[48]Appointments were to be based on merit instead of hereditary right.[48]

Economic reforms

Qin Shi Huang andLi Siunified China economically by standardizing theweights and measurements.Wagon axles were prescribed a standard length to facilitate road transport.[47]The emperor also developed an extensive network of roads and canals for trade and communication.[47]The currencies of the different states were standardized to theBan Liangcoin.[48]The forms ofChinese characterswere unified. Under Li Si, theseal scriptof the state of Qin became the official standard, and the Qin script itself was simplified through removal of variant forms. This did away with all the regional scripts to form a universal written language for all of China, despite the diversity of spoken dialects.[48]

Monumental statuary

According to Chinese records,[49]after unifying the country in 221 BC, Qin Shuhuang confiscated all the bronze weapons of the conquered countries, and cast them into twelve monumental statues, theTwelve Metal Colossi,which he used to adorn his Palace.[50]Each statue was said to be 5 zhang [11.5 meters] in height, and weighing about 1000 dan [about 70 tons].[51]Sima Qian considered this as one of the great achievements of the Emperor, on a par with the "unification of the law, weights and measurements, standardization of the axle width of carriages, and standardization of the writing system".[49][52]During 600 years, the statues were commented upon and moved around from palace to palace, until they were finally destroyed in the 4th century AD, but no illustration has remained.[53][54]

Philosophy

| Part of a series on |

| Chinese legalism |

|---|

|

While the previous Warring States era was one of constant warfare, it was also considered the golden age of free thought.[55]Qin Shi Huang eliminated theHundred Schools of Thought,which includedConfucianismand other philosophies.[55][56]With all other philosophies banned,Legalismbecame the mandatory ideology of the Qin dynasty.[48]

Beginning in 213 BC, at the instigation of Li Si and to avoid scholars' comparisons of his reign with the past, Qin Shi Huang ordered most existingbooks to be burned,with the exception of those on astrology, agriculture, medicine, divination, and the history of thestate of Qin.[57]This would also serve to further the ongoing reformation of the writing system by removing examples of obsolete scripts.[58]Owning theClassic of Poetryor theBook of Documentswas to be punished especially severely. According to the laterShiji,the following year Qin Shi Huang had some 460 scholars buried alive for possessing the forbidden books.[24][57]The emperor's oldest sonFusucriticised him for this act.[59]The emperor's own library did retain copies of the forbidden books, but most of these were destroyed whenXiang Yuburned the palaces of Xianyang in 206 BC.[60]

Recent research suggests that this "burying Confucian scholars alive" is a Confucian martyrs' legend. More probably, the emperor ordered the execution of a group of alchemists who had deceived him. In the subsequent Han dynasty, the Confucian scholars, who had served the Qin loyally, used this incident to distance themselves from the failed regime.Kong Anguo(c. 165– c. 74 BC), a descendant of Confucius, described the alchemists as Confucianists and entwined the martyrs' legend with his story of discovering the lost Confucian books behind a demolished wall in his ancestral house.[61]

Qin Shi Huang also followed the theory of thefive elements:fire, water, earth, wood, and metal. It was believed that the royal house of the previousZhou dynastyhad ruled by the power of fire, associated with the colour red. The new Qin dynasty must be ruled by the next element on the list, which is water, Zhao Zheng's birth element. Water was represented by the colour black, and black became the preferred colour for Qin garments, flags, and pennants.[24]Other associations include north as thecardinal direction,the winter season and the number six.[62]Tallies and official hats were 15 centimetres (5.9 inches) long, carriages two metres (6.6 feet) wide, onepace(Bộ;bù) was 1.4 m (4.6 ft).[24]

Third assassination attempt

In 230 BC, the state of Qin had defeated thestate of Han.In 218, a former Han aristocrat namedZhang Liangswore revenge on Qin Shi Huang. He sold his valuables and hired a strongman assassin, building a heavy metal cone weighing 120catties(roughly 160 lb or 97 kg).[42]The two men hid among the bushes along the emperor's route over a mountain during his third imperial tour.[63]At a signal, the muscular assassin hurled the cone at the first carriage and shattered it. However, the emperor was travelling with two identical carriages to baffle attackers, and he was actually in the second carriage. Thus the attempt failed,[64]though both men were able to escape the subsequent manhunt.[42]

Public works

Great Wall

Numerous state walls had been built during the previous four centuries, many of them closing gaps between river defences and impassable cliffs.[65][66]To impose centralized rule and prevent the resurgence of feudal lords, the Emperor ordered the destruction of walls between the former states, which were now internal walls dividing the empire.

However, to defend against the northernXiongnunomads, who had beaten back repeated campaigns against them, he ordered new walls to connect the fortifications along the empire's northern frontier. Hundreds of thousands of workers were mobilized, and an unknown number died, to build this precursor to the currentGreat Wall of China.[67][68][69]Transporting building materials was difficult, so builders always tried to use local materials: rock over mountain ranges,rammed earthover the plains. "Build and move on" was a guiding principle, implying that the Wall was not a permanently fixed border.[70]There are no surviving records specifying the length and course of the Qin walls, which have largely eroded away over the centuries.

Lingqu Canal

In 214 BC the Emperor began the project of a major canal allowing water transport between north and south China, originally for military supplies.[71]The canal, 34 kilometres in length, links two of China's major waterways, theXiang Riverflowing into theYangtzeand theLijiang River,flowing into thePearl River.[71]The canal aided Qin's expansion to the south-west.[71]It is considered one of the three great feats of ancient Chinese engineering, along with the Great Wall and the SichuanDujiangyan Irrigation System.[71]

Elixir of life

As he grew old, Qin Shi Huang desperately sought the fabledelixir of lifewhich supposedly confers immortality. In his obsessive quest, he fell prey to many fraudulent elixirs.[72]He visitedZhifu Islandthree times in his search.[73]

In one case he sentXu Fu,a Zhifu islander, with ships carrying hundreds of young men and women in search of the mysticalMount Penglai.[64]They soughtAnqi Sheng,a thousand-year-old magician who had supposedly invited Qin Shi Huang during a chance meeting during his travels.[74]The expedition never returned, perhaps for fear of the consequences of failure. Legends claim that they reached Japan and colonized it.[72]

It is also possible that the Emperor's book burning, which exemptedalchemicalworks, could be seen as an attempt to focus the minds of the best scholars on the Emperor's quest.[75]Some of those buried alive were alchemists, and this could have been a means of testing their death-defying abilities.[76]

The emperor built a system of tunnels and passageways to each of his over 200 palaces,[citation needed]because traveling unseen would supposedly keep him safe from evil spirits.

Final years

Death

In 211 BC, a large meteor is said to have fallen inDongjunin the lower reaches of theYellow River,and someone inscribed the seditious words "The First Emperor will die and his land will be divided" (Thủy hoàng tử nhi địa phân).[77]The Emperor sent an imperial secretary to investigate this prophecy. No one would confess to the deed, so all living nearby were put to death, and the stone was pulverized.[78]

During his fifth tour of eastern China, the Emperor became seriously ill in Pingyuanjin (Pingyuan County, Shandong), and died in July or August of 210 BC, at the palace in Shaqiuprefecture,about two months travel from Xianyang,[79][80]at the age of 49.

The cause of Qin Shi Huang's death remains unknown, though he had been worn down by his many years of rule.[81]One hypothesis holds that he waspoisoned by an elixircontainingmercury,given to him by his court alchemists and physicians in his quest for immortality.[82]

Succession

Upon witnessing the Emperor's death, ChancellorLi Sifeared the news could trigger a general uprising during the two months' travel for the imperial entourage to return to the capital Xianyang.[10]Li Si decided to hide the emperor's death: the only members of the entourage to be informed were a younger son,Ying Huhai,the eunuchZhao Gao,and five or six favourite eunuchs.[10]Li Si ordered carts of rotten fish to be carried before and behind the wagon of the Emperor, to cover the foul smell of his body decomposing in the summer heat.[10]Pretending he was alive behind the wagon's shade, they changed his clothes daily, brought food, and pretended to carry messages to and from him.[10]

After they reached Xianyang, the death of the Emperor was announced.[10]Qin Shi Huang had not liked to talk about his death and had never written a will.[83]Although his eldest sonFusuwas first in line to succeed him as emperor, Li Si and the chief eunuch Zhao Gao conspired to kill Fusu, who was in league with their enemy, generalMeng Tian.[83]Meng Tian's brother, a senior minister, had once punished Zhao Gao.[84]Li Si and Zhao Gao forged a letter from Qin Shi Huang commanding Fusu and General Meng to commit suicide.[83]The plan worked, and the younger son Hu Hai started his brief reign as the Second Emperor, later known asQin Er Shior "Second Generation Qin".[10]

Family

The immediate family members of Qin Shi Huang include:

- Parents[85]

- Half-siblings:

- Chengjiao,legitimate paternal half brother from a different mother[86]Lord of Chang'an[40]

- Two illegitimate maternal half-brothers born toQueen Dowager ZhaoandLao Ai.

- Children:

- Fusu,Crown Prince (1st son)[87]

- Gao

- Jianglü

- Huhai,laterQin Er Shi(18th son)[87]

Qin Shi Huang had about 50 children (about 30 sons and 15 daughters), but most of their names are unknown. He had numerousconcubinesbut appeared to have never named an empress.[88]

| Qin Dynasty | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Legacy

Mausoleum and Terracotta Army

Sima Qian, writing a century after the First Emperor's death, wrote that it took 700,000 men to construct theemperor's mausoleum.British historianJohn Manpoints out that this figure is larger than the population of any city in the world at that time and he calculates that the foundations could have been built by 16,000 men in two years.[90]Sima Qian never mentioned theTerracotta Army,but he did mention that the Qin Emperor built monumental bronze statues for his palace.[91]The terracotta statues were discovered by a group of farmers digging wells on 29 March 1974.[92]The soldiers were created with a series of mix-and-match clay molds and then further individualized by the artists' hand.Han Purplewas also used on some of the warriors.[93] There are around 6,000 statues, whose purpose was to protect the Emperor in the afterlife from evil spirits.[94]Also among the army are chariots and 40,000 real bronze weapons.[95]

One of the first projects which the young king accomplished while he was alive was the construction of his own tomb. In 215 BC Qin Shi Huang ordered GeneralMeng Tianto begin its construction with the assistance of 300,000 men.[24]Other sources suggest that he ordered 720,000 unpaid laborers to build his tomb according to his specifications.[38]Again, given John Man's observation regarding populations at the time (see paragraph above), these historical estimates are debatable. The main tomb (located at34°22′53″N109°15′13″E/ 34.38139°N 109.25361°E) containing the emperor has yet to be opened and evidence suggests that it remains relatively intact.[96]Sima Qian's description of the tomb includes replicas of palaces and scenic towers, "rare utensils and wonderful objects", 100 rivers made with mercury, representations of "the heavenly bodies", and crossbows rigged to shoot anyone who tried to break in.[97]The tomb was built at the foot ofMount Li,30 kilometers away from Xi'an. Modern archaeologists have located the tomb, and have inserted probes deep into it. The probes revealed abnormally high quantities of mercury, some 100 times the naturally occurring rate, suggesting that some parts of the legend are credible.[82]Secrets were maintained, as most of the workmen who built the tomb were killed.[82][98]

Reputation and assessment

Traditional Chinesehistoriographyalmost always portrayed the Emperor as a brutal tyrant who had an obsessive fear of assassination. Ideological antipathy towards theLegalistState of Qin was established as early as 266 BC, when Confucian philosopherXunzidisparaged it.[citation needed]Later Confucian historians condemned the emperor, alleging that heburned the classics and buried Confucian scholars alive.[99]They eventually compiled a list of theTen Crimes of Qinto highlight his tyrannical actions.[100]

The famous Han poet and statesmanJia Yiconcluded his essayThe Faults of Qin( quá tần luận,Guò Qín Lùn) with what was to become the standard Confucian judgment of the reasons for Qin's collapse. Jia Yi's essay, admired as a masterpiece of rhetoric and reasoning, was copied into two great Han histories and has had a far-reaching influence on Chinese political thought as a classic illustration of Confucian theory.[101]He attributed Qin's disintegration to its internal failures.[102]Jia Yi wrote that:

Qin, from a tiny base, had become a great power, ruling the land and receiving homage from all quarters for a hundred odd years. Yet after they unified the land and secured themselves within the pass, a single common rustic could nevertheless challenge this empire... Why? Because the ruler lacked humaneness and rightness; because preserving power differs fundamentally from seizing power.[103]

In the modern period, assessments began to emerge that differed from those of traditional historiography. The reassessment was spurred on by the weakness of China in the latter half of the 19th century and early 20th century. At that time, some began to regard Confucian traditions as an impediment to China's entry into the modern world, opening the way for changing perspectives.

At a time when foreign nations encroached upon Chinese territory, leadingKuomintanghistorianXiao Yishanemphasized the role of Qin Shi Huang in repulsing the northern barbarians, particularly in the construction of the Great Wall.

Another historian, Ma Feibai (Mã phi bách), published in 1941 a full-length revisionist biography of the First Emperor entitledQín Shǐ Huángdì Zhuàn(Tần thủy hoàng đế truyện), calling him "one of the great heroes of Chinese history". Ma compared him with the contemporary leaderChiang Kai-shekand saw many parallels in the careers and policies of the two men, both of whom he admired. Chiang'sNorthern Expeditionof the late 1920s, which directly preceded the new Nationalist government atNanjingwas compared to the unification brought about by Qin Shi Huang.

With the advent of theChinese Communist Revolutionand the establishment of a new, revolutionary regime in 1949, another re-evaluation of the First Emperor emerged as a Marxist critique. This new interpretation of Qin Shi Huang was generally a combination of traditional and modern views, but essentially critical. This is exemplified in theComplete History of China,which was compiled in September 1955 as an official survey of Chinese history. The work described the First Emperor's major steps toward unification and standardisation as corresponding to the interests of the ruling group and the merchant class, not of the nation or the people, and the subsequent fall of his dynasty as a manifestation of theclass struggle.The perennial debate about the fall of the Qin dynasty was also explained in Marxist terms, the peasant rebellions being a revolt against oppression—a revolt which undermined the dynasty, but which was bound to fail because of a compromise with "landlord class elements".

Since 1972, however, a radically different official view of Qin Shi Huang in accordance withMaoistthought has been given prominence throughout China. Hong Shidi's biographyQin Shi Huanginitiated the re-evaluation. The work was published by the state press as a mass popular history, and it sold 1.85 million copies within two years. In the new era, Qin Shi Huang was seen as a far-sighted ruler who destroyed the forces of division and established the first unified, centralized state in Chinese history by rejecting the past. Personal attributes, such as his quest for immortality, so emphasized in traditional historiography, were scarcely mentioned. The new evaluations described approvingly how, in his time (an era of great political and social change), he had no compunctions against using violent methods to crushcounter-revolutionaries,such as the "industrial and commercial slave owner" chancellor Lü Buwei. However, he was criticized for not being as thorough as he should have been, and as a result, after his death, hidden subversives under the leadership of the chief eunuchZhao Gaowere able to seize power and use it to restore the old feudal order.

To round out this re-evaluation, Luo Siding put forward a new interpretation of the precipitous collapse of the Qin dynasty in an article entitled "On the Class Struggle During the Period Between Qin and Han" in a 1974 issue ofRed Flag,to replace the old explanation. The new theory claimed that the cause of the fall of Qin lay in the lack of thoroughness of Qin Shi Huang's "dictatorship over the reactionaries, even to the extent of permitting them to worm their way into organs of political authority and usurp important posts."

Mao Zedong's persecution of intellectuals was compared to that of the First Emperor.[104]On his being made aware of having been compared as such, Mao reportedly boasted:

He buried 460 scholars alive; we have buried forty-six thousand scholars alive... You [intellectuals] revile us for being Qin Shi Huangs. You are wrong. We have surpassed Qin Shi Huang a hundredfold. When you berate us for imitating his despotism, we are happy to agree! Your mistake was that you did not say so enough.[105]

Depictions in popular media

- "The Wall and the Books" ( "La muralla y los libros"), an acclaimed essay on Qin Shi Huang published by Argentine writerJorge Luis Borges(1899–1986) in the 1952 collectionOther Inquisitions(Otras Inquisiciones).[106]

- The Emperor's Shadow(1996) – The film focuses on Qin Shi Huang's relationship with the musicianGao Jianli,a friend of the assassinJing Ke.[107]

- The Emperor and the Assassin(1999) – The film covers much of Ying Zheng's career, recalling his early experiences as a hostage and foreshadowing his dominance over China.[108][109]

- Hero(2002) – The film starsJet Li,a nameless assassin who plans an assassination attempt on the King of Qin (Chen Daoming). The film is a fictional re-imagining of the assassination attempt by Jing Ke on Qin Shi Huang.[110]

- Rise of the Great Wall(1986) – a 63-episode Hong Kong TV series chronicling the events from the emperor's birth until his death.[111]Tony Liuplayed Qin Shi Huang.

- A Step into the Past(2001) – a Hong KongTVBproduction based on a science fiction novel byHuang Yi.[112]

- Qin Shi Huang(2002) – a mainland Chinese TV semi-fictionalized series withZhang Fengyi.[113]

- Kingdom(2006) – a Japanese manga that provides a fictionalized account of the unification of China by Ying Zheng withLi Xinand all the people that contributed to the conquest of the sixWarring States.

- Fate/Grand Order(2015), an online, free-to-play role-playing mobile game of theFatefranchise developed by Delightworks and published byAniplexfeatures Qin Shi Huang as a Ruler class servant.[114]

- Civilization VI(2016), aturn-based strategy4Xvideo game developed byFiraxis Gamesand published by2Kfeatures Qin Shi Huang as a playable leader.[115]

- First Emperor: The Man Who Made China(2006) – a drama-documentary special about Qin Shi Huang.James Paxplayed the emperor. It was shown onChannel 4in theUnited Kingdomin 2006.[116]

- China's First Emperor(2008) – a special three-hour documentary byThe History Channel.Xu Pengkai played Qin Shi Huang.[117]

- The Mummy: Tomb of the Dragon Emperor(2008) – the third ofThe Mummytrilogy.It happened that after General Ming Guo was killed for touching Zi Yuan, she put a curse on the Emperor and his army.

- Qin Shi Huang is depicted in seventh volume of the mangaRecord of Ragnarok,fightingHades.In the manga, he is depicted as a tall slender young man with a cloth covering his eye. He is also shown to be wearing traditional Chinese clothing.[118]

Notes

- ^This 19th-century posthumous depiction is from a Korean book now kept in theBritish Library.[1]It is based on a portrait of Qin Shi Huang from theSancai Tuhui.[2]

- ^Volume 90ofTreatise on Astrology of the Kaiyuan Era(8th century) indicates that he died on theyichouday of the 6th month of the 38th year of his reign (starting from his tenure as King of Qin), which corresponds to 11 July 210 BCE on theproleptic Julian calendar( thủy hoàng dĩ lục nguyệt ất sửu tử vu sa khâu...).Volume 6ofRecords of the Grand Historian(1st century BC) indicates that he died on thebingyinday of the 7th month of his 38th year. While there is nobingyinday in that month, there is abingyinday in the previous month, which corresponds to 12 July 210 BCE on the prolepticJulian calendar( thất nguyệt bính dần, thủy hoàng băng vu sa khâu bình đài. ) Older methods of calculation give 18 July.[3]A few modern sources give 10 September,[4][5]thebingyinday of the 8th month on theproleptic Julian calendar.Modern authors usually don't use specific dates.[6][7]

- ^Volume 05ofRecords of the Grand Historianindicated that King Zhuangxiang died on thebingwuday of the 5th month of the 4th year of his reign. Using theZhuanxucalendar, the date corresponds to 6 Jul 247 BC on theproleptic Julian calendar.([ tứ niên ].... Ngũ nguyệt bính ngọ, trang tương vương tốt...)

- ^Volume 06ofRecords of the Grand Historianindicated that Ying Zheng was born in thezhengyueof the 48th year of the reign of King Zhao(xiang) of Qin. Using theZhuanxucalendar, the month corresponds to 27 Jan to 24 Feb 259 BC in the proleptic Julian calendar. ( dĩ tần chiêu vương tứ thập bát niên chính nguyệt sinh vu hàm đan. )

- ^Volume 06ofRecords of the Grand Historianindicated that Ying Zheng was born in thezhengyueof the 48th year of the reign of King Zhao(xiang) of Qin. Using theZhuanxucalendar, the month corresponds to 27 Jan to 24 Feb 259 BC in the proleptic Julian calendar. ( dĩ tần chiêu vương tứ thập bát niên chính nguyệt sinh vu hàm đan. )

- ^In simplified Chinese,Cập sinh, danh vi chính, tính triệu thị.[13]The differentiation between the two types of surnames had largely been lost well before Sima Qian's time, as can be seen from his grammatical construction usingTínhas a verb – "to be surnamed" – with the objectThị,a different kind of surname.

- ^See Nienhauser's gloss of the name Zhao Zheng (n. 579).[14]

- ^While the specific title was new, also note the use ofHoàng thiên thượng đế( "August HeavenShangdi"), a conflation of the Zhou and Shang gods by theDuke of Zhouused in his addresses to the conquered Shang peoples.[25]

- ^That both were forbidden has been the general understanding of historians but Beck cites numerous sources from the era employing the latter character in support of the argument that it was not forbidden until the reign of theSecond Emperor of Qin.[29]

- ^His father's nameTử sởalso became taboo, prompting references toChuto be replaced by its original name "Jing" (Kinh).[29]

References

- ^abClements 2006,Between pp. 76–77.

- ^Portal 2007,p. 29.

- ^Moule, Arthur C.(1957).The Rulers of China, 221 BC-AD 1949.London: Routledge. p. 3.OCLC223359908.

- ^Farquhar, Michael (2006).Bad Days in History: A Gleefully Grim Chronicle of Misfortune, Mayhem, and Misery for Every Day of the Year.Tịch thiên văn hóa. p. 16.ISBN9789861840239.

- ^Farquhar, Michael (2015).Bad Days in History: A Gleefully Grim Chronicle of Misfortune, Mayhem, and Misery for Every Day of the Year.National Geographic. p. 324.ISBN978-1-4262-1280-2.

- ^abLoewe 2000,p. 823.

- ^Barbieri-Low & Yates 2015,p.xix.

- ^Paludan 1998,p. 16.

- ^Müller 2021,"Introduction".

- ^abcdefghijSima 2007,pp. 15–20, 82, 99.

- ^Loewe 2000,p. 654.

- ^abSima 1994,p. 127.

- ^abzh[Sima Qian].《 sử ký 》[Shiji],Tần thủy hoàng bổn kỷ đệ lục[ "§6: Basic Annals of the First Emperor of Qin" ]. Hosted atQuốc học võng[Guoxue.com], 2003. Accessed 25 December 2013.(in Chinese)

- ^abSima 1994,p. 439.

- ^Sima 1994,p. 123.

- ^Sima Qian.Shiji,Tần bổn kỷ đệ ngũ[ "§5: Basic Annals of Qin" ]. Hosted atQuốc học võng[Guoxue.com], 2003. Accessed 25 December 2013.(in Chinese)

- ^abWilkinson, Endymion.Chinese History: A Manual,pp. 108 ffArchived25 December 2019 at theWayback Machine.Harvard University Press (Cambridge, MA), 2000.ISBN0-674-00247-4.Accessed 26 December 2013.

- ^Luo Zhewen & al.The Great Wall,p. 23. McGraw-Hill, 1981.ISBN0-07-070745-6.

- ^Fowler, Jeaneane D.An Introduction to the Philosophy and Religion of Taoism: Pathways to Immortality,p. 132. Sussex Academic Press, 2005.ISBN1-84519-086-6.

- ^Tư mã thiên[Sima Qian].《 sử ký 》[Shiji],Tần bổn kỷ đệ ngũArchived13 June 2022 at theWayback Machine[ "§5: Basic Annals of Qin" ]. Hosted atDuy cơ văn khố[Chinese Wikisource], 2012. Accessed 27 December 2013.(in Chinese)

- ^Hardy, Grant & al.The Establishment of the Han Empire and Imperial China,p. 10. Greenwood, 2005.ISBN0-313-32588-X.

- ^Major, John.Heaven and Earth in Early Han Thought: Chapters Three, Four, and Five of theHuainanzi,p. 18Archived21 December 2019 at theWayback Machine.SUNY Press (New York), 1993. Accessed 26 December 2013.

- ^Kern, Martin. "The stele inscriptions of Ch'in Shih-huang: text and ritual in early Chinese imperial representation". American Oriental Society, 2000.

- ^abcdefghiWood, Frances. (2008).China's First Emperor and His Terracotta Warriors,pp. 2–33. Macmillan Publishing, 2008.ISBN0-312-38112-3.

- ^abCreel, Herrlee G.The Origins of Statecraft in China,pp. 495 ff. University of Chicago Press (Chicago), 1970. Op. cit. Chang, Ruth. "Understanding Di and Tian: Deity and Heaven from Shang to Tang DynastiesArchived28 June 2017 at theWayback Machine",pp. 13–14.Sino-Platonic Papers,No. 108. Sept. 2000. Accessed 27 December 2013.

- ^Lewis, Mark.The Early Chinese Empires: Qin and Han,p. 52Archived5 May 2016 at theWayback Machine.Belknap Press (|Cambridge, MA), 2009.ISBN978-0-674-02477-9.Accessed 27 December 2013.

- ^Chang, "Understanding Di and Tian", 4–9.

- ^Tư mã thiên[Sima Qian].《 sử ký 》[Shiji],Tần thủy hoàng bổn kỷ đệ lụcArchived15 June 2022 at theWayback Machine[ "§6: Basic Annals of the First Emperor of Qin" ]. Hosted atDuy cơ văn khố[Chinese Wikisource], 2012. Accessed 27 December 2013.(in Chinese)

- ^abBeck, B.J. Mansvelt. "The First Emperor's Taboo Character and the Three Day Reign of King Xiaowen: Two Moot Points Raised by the Qin Chronicle Unearthed in Shuihudi in 1975Archived2 June 2016 at theWayback Machine".T'oung Pao2nd Series, Vol. 73, No. 1/3 (1987), p. 69.

- ^abSima 1993,pp. 35, 59.

- ^Sima Qian;Sima Tan(1959) [90s BCE]. "vol. 6, Basic annals of Qin Shihuang".ShijiSử ký tam gia chú[Records of the Grand Historian] (in Chinese) (annotated critical ed.). Beijing: Zhonghua Shuju.

- ^abRen Changhong & al.Rise and Fall of the Qin Dynasty.Asiapac, 2000.ISBN981-229-172-5.

- ^abHuang, Ray.China: A Macro HistoryEdition: 2, revised. (1987). M. E. Sharpe.ISBN1-56324-730-5,978-1-56324-730-9.p. 32.

- ^Lü, Buwei. Translated by Knoblock, John. Riegel, Jeffrey.The Annals of Lü Buwei:Lü Shi ChunQiu: a Complete Translation and Study.(2000). Stanford University Press.ISBN0-8047-3354-6,978-0-8047-3354-0.

- ^Bodde 1986,pp. 42–43, 95.

- ^The Annals of Lü Buwei.Knoblock, John and Riegel, Jeffrey Trans. Stanford University Press. 2001.ISBN978-0-8047-3354-0.

{{cite book}}:CS1 maint: others (link)p. 9 - ^Bodde 1986,p. 43.

- ^abDonn, Lin. Donn, Don.Ancient China.(2003). Social Studies School Service. Social Studies.ISBN1-56004-163-3,978-1-56004-163-4.p. 49.

- ^Pancella, Peggy (2003).Qin Shi Huangdi: First Emperor of China.Heinemann-Raintree Library.ISBN978-1-4034-3704-4.Archivedfrom the original on 18 May 2021.Retrieved21 October2020.

- ^abTư mã thiên 《 sử ký · quyển 043· triệu thế gia 》: ( triệu điệu tương vương ) lục niên, phong trường an quân dĩ nhiêu.

- ^ShijiChapter – Qin Shi Huang: Bát niên, vương đệ trường an quân thành kiểu tương quân kích triệu, phản, tử truân lưu, quân lại giai trảm tử, thiên kỳ dân ô lâm thao. Tương quân bích tử, tốt truân lưu, bồ 鶮 phản, lục kỳ thi. Hà ngư đại thượng, khinh xa trọng mã đông tựu thực. 《 sử ký tần thủy hoàng 》

- ^abcdefghiMah, Adeline Yen. (2003).A Thousand Pieces of Gold: Growing Up Through China's Proverbs.Published by HarperCollins.ISBN0-06-000641-2,978-0-06-000641-9.pp. 32–34.

- ^The Records of the Grand Historian, Vol. 6: Annals of Qin Shi Huang.[1]Archived14 April 2013 atarchive.todayThe 9th year of Qin Shi Huang. Vương tri chi, lệnh tương quốc xương bình quân, xương văn quân phát tốt công ái. Chiến hàm dương, trảm thủ sổ bách, giai bái tước, cập hoạn giả giai tại chiến trung, diệc bái tước nhất cấp. Ái đẳng bại tẩu.

- ^Elizabeth, Jean. Ward, Laureate. (2008).The Songs and Ballads of Li He Chang.ISBN1-4357-1867-4,978-1-4357-1867-8.p. 51

- ^Wu, Hung.The Wu Liang Shrine: The Ideology of Early Chinese Pictorial Art.Stanford University Press, 1989.ISBN0-8047-1529-7,978-0-8047-1529-4.p. 326.

- ^abHaw, Stephen G. (2007).Beijing a Concise History.Routledge.ISBN978-0-415-39906-7.pp. 22–23.

- ^abcVeeck, Gregory. Pannell, Clifton W. (2007).China's Geography: Globalization and the Dynamics of Political, Economic, and Social Change.Rowman & Littlefield publishing.ISBN0-7425-5402-3,978-0-7425-5402-3.pp. 57–58.

- ^abcdefChang, Chun-shu (2007), "The rise of the Chinese Empire",Nation, State, and Imperialism in Early China ca. 1600 BC–8 AD,University of Michigan Press, pp. 43–44,ISBN978-0-472-11533-4

- ^abShijiby Sima Qian (c. 145–86 BC), afterLiu Anin theHuainanzicirca 139 BC: Thu thiên hạ binh, tụ chi hàm dương, tiêu dĩ vi chung cự kim nhân thập nhị, trọng các thiên thạch, trí đình cung trung. Nhất pháp độ hành thạch trượng xích. Xa đồng quỹ. Thư đồng văn tự.

"He collected the weapons of All-Under-Heaven inXianyang,and cast them into twelve bronze figures of the type of bell stands, each 1000 dan [about 70 tons] in weight, and displayed them in the palace. He unified the law, weights and measurements, standardized the axle width of carriages, and standardized the writing system. "

QuotedNickel, Lukas (October 2013)."The First Emperor and sculpture in China".Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies.76(3): 436–450.doi:10.1017/S0041977X13000487.ISSN0041-977X. - ^Lei, Haizong (2020).Chinese Culture and the Chinese Military.Cambridge University Press. pp. 13–14.ISBN978-1-108-47918-9.

- ^Nickel, Lukas (October 2013)."The First Emperor and sculpture in China".Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies.76(3): 436–450.doi:10.1017/S0041977X13000487.ISSN0041-977X.

- ^Howard, Angela Falco; Hung, Wu; Song, Li; Hong, Yang (2006).Chinese Sculpture.Yale University Press. p. 50.ISBN978-0-300-10065-5.

- ^Barnes, Gina L. (2015).Archaeology of East Asia: The Rise of Civilization in China, Korea and Japan.Oxbow. p. 287.ISBN978-1-78570-073-6.

- ^Elsner, Jaś (2020).Figurines: Figuration and the Sense of Scale.Oxford University Press.ISBN978-0-19-886109-6.

- ^abGoldman, Merle. (1981).China's Intellectuals: Advise and Dissent.Harvard University Press.ISBN0-674-11970-3,978-0-674-11970-3.p. 85.

- ^Chaurasia, Radhey Shyam. (2004).History of Modern China.Atlantic Publishers & Distributors.ISBN81-269-0315-5,978-81-269-0315-3.p. 317.

- ^abLi-Hsiang Lisa Rosenlee. Ames, Roger T. (2006).Confucianism and Women: A Philosophical Interpretation.SUNY Press.ISBN0-7914-6749-X,978-0-7914-6749-7.p. 25.

- ^Clements 2006,p. 131.

- ^Twitchett, Denis. Fairbank, John King. Loewe, Michael.The Cambridge History of China: The Ch'in and Han Empires 221 B.C.–A.D. 220.Edition: 3. Cambridge University Press, 1986.ISBN0-521-24327-0,978-0-521-24327-8.p. 71.

- ^Sima 2007,pp. 74–75, 119, 148–49.

- ^Neininger, Ulrich,Burying the Scholars Alive: On the Origin of a Confucian Martyrs' Legend,Nation and Mythology(inEast Asian Civilizations. New Attempts at Understanding Traditions), vol. 2, 1983, eds. Wolfram Eberhard et al., pp. 121–36.ISBN3-88676-041-3.http://www.ulrichneininger.de/?p=461Archived14 April 2021 at theWayback Machine

- ^Murowchick, Robert E. (1994).China: Ancient Culture, Modern Land.University of Oklahoma Press, 1994.ISBN0-8061-2683-3,978-0-8061-2683-8.p. 105.

- ^Sanft, Charles (2014)."Outline of the Progress / 218 BCE: Third Progress".Communication and Cooperation in Early Imperial China: Publicizing the Qin Dynasty.State University of New York Press. pp. 79–84.ISBN978-1438450377.

- ^abWintle, Justin Wintle. (2002).China.Rough Guides Publishing.ISBN1-85828-764-2,978-1-85828-764-5.pp. 61, 71.

- ^Clements 2006,pp. 102–103.

- ^Huang, Ray. (1997).China: A Macro History.Edition: 2, revised, illustrated. M. E. Sharpe.ISBN1-56324-731-3,978-1-56324-731-6.p. 44

- ^Slavicek, Louise Chipley; Mitchell, George J.; Matray, James I. (2005).The Great Wall of China.Infobase. p.35.ISBN978-0-7910-8019-1.

- ^Evans, Thammy (2006). Great Wall of China: Beijing & Northern China. Bradt Travel Guide. Bradt Travel Guides. p. 3.ISBN978-1-84162-158-6

- ^"Defense and Cost of The Great Wall"Archived17 June 2013 at theWayback Machine.Paul and Bernice Noll's Window on the World. p. 3. Retrieved 26 July 2011.

- ^Burbank, Jane; Cooper, Frederick (2010). Empires in World History: Power and the Politics of Difference. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. p. 45.

- ^abcdMayhew, Bradley. Miller, Korina. English, Alex.South-West China: lively Yunnan and its exotic neighbours.Lonely Planet.ISBN1-86450-370-X,978-1-86450-370-8.p. 222.

- ^abOng, Siew Chey. Marshall Cavendish. (2006).China Condensed: 5000 Years of History & Culture.ISBN981-261-067-7,978-981-261-067-6.p. 17.

- ^Aikman, David. (2006). Qi. Publishing Group.ISBN0-8054-3293-0,978-0-8054-3293-0.p. 91.

- ^Fabrizio Pregadio.The Encyclopedia of Taoism.London: Routledge, 2008: 199

- ^"Qin Shi Huang: The ruthless emperor who burned books".BBC.12 October 2012.Retrieved24 November2022.

- ^Clements 2006,pp. 131, 134.

- ^Liang, Yuansheng. (2007).The Legitimation of New Orders: Case Studies in World History.Chinese University Press.ISBN962-996-239-X,978-962-996-239-5.p. 5.

- ^Sima 1993,pp. 35 & 59.

- ^Sima 2007,p. 82, "In the seventh month onbingyinthe First Emperor passed away at Pingtai in Shaqiu. ".

- ^Xinhuanet.com. ""Trung quốc khảo cổ giản tấn: Tần thủy hoàng khứ thế địa sa khâu bình đài di tích thượng tồn.Archived18 March 2009 at theWayback MachineXinhuanet. Retrieved on 28 January 2009.

- ^Barme, Geremie R. (2009)."China's Flat Earth: History and 8 August 2008".The China Quarterly.197:64–86.doi:10.1017/S0305741009000046.hdl:1885/52104.ISSN0305-7410.S2CID154584809.Archivedfrom the original on 31 July 2022.Retrieved24 June2020.

- ^abcWright, David Curtis (2001).The History of China.Greenwood. p.49.ISBN978-0-313-30940-3.

- ^abcTung, Douglas S. Tung, Kenneth. (2003).More Than 36 Stratagems: A Systematic Classification Based On Basic Behaviours.Trafford Publishing.ISBN1-4120-0674-0,978-1-4120-0674-3.

- ^Sima 2007,p. 54.

- ^Clements 2006,p. 172.

- ^"Sử ký / quyển 006 – duy cơ văn khố, tự do đích đồ thư quán".zh.wikisource.org.Archivedfrom the original on 15 June 2022.Retrieved31 July2022.

- ^ab《 sử ký · cao tổ bổn kỷ 》 tư mã trinh 《 tác ẩn 》 tả đạo: "《 thiện văn 》 xưng ẩn sĩ vân triệu cao vi nhị thế sát thập thất huynh nhi lập kim vương, tắc nhị thế thị đệ thập bát tử dã."

- ^Trương văn lập: 《 tần thủy hoàng đế bình truyện 》, thiểm tây nhân dân giáo dục xuất bản xã, 1996, đệ 325~326 hiệt.

- ^Williams, A. R. (12 October 2016)."Discoveries May Rewrite History of China's Terra-Cotta Warriors".National Geographic.Archived fromthe originalon 28 February 2021.

- ^Man, John.The Terracotta Army,Bantam 2007 p. 125.ISBN978-0-593-05929-6.

- ^Nickel, Lukas (October 2013)."The First Emperor and sculpture in China".Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies.76(3): 436–450.doi:10.1017/S0041977X13000487.ISSN0041-977X.

- ^Huang, Ray. (1997).China: A Macro History.Edition: 2, revised, illustrated. M. E. Sharpe.ISBN1-56324-731-3,978-1-56324-731-6.p. 37

- ^Thieme, C. 2001. (translated by M. Will)Paint Layers and Pigments on the Terracotta Army: A Comparison with Other Cultures of Antiquity.In: W. Yongqi, Z. Tinghao, M. Petzet, E. Emmerling and C. Blänsdorf (eds.)The Polychromy of Antique Sculptures and the Terracotta Army of the First Chinese Emperor: Studies on Materials, Painting Techniques and Conservation.Monuments and Sites III.Paris: ICOMOS, 52–57.

- ^"The dark history behind the record-breaking Terracotta Army".Guinness World Records.11 March 2022.Retrieved24 November2022.

- ^Portal 2007,p.[page needed].

- ^Portal 2007,p. 207.

- ^Man, John.The Terracotta Army,Bantam 2007 p. 170.ISBN978-0-593-05929-6.

- ^Leffman, David. Lewis, Simon. Atiyah, Jeremy. Meyer, Mike. Lunt, Susie. (2003).China.Edition: 3, illustrated. Rough Guides publishing.ISBN1-84353-019-8,978-1-84353-019-0.p. 290.

- ^Neininger, Ulrich (1983), "Burying the Scholars Alive: On the Origin of a Confucian Martyrs' Legend", Nation and Mythology ", in Eberhard, Wolfram (ed.),East Asian Civilizations. New Attempts at Understanding Traditions vol. 2,pp. 121–136OnlineArchived10 March 2022 at theWayback Machine

- ^Ærenlund Sørensen, "How the First Emperor Unified the Minds Of Contemporary Historians: The Inadequate Source Criticism in Modern Historical Works About The Chinese Bronze Age."Monumenta Serica,vol. 58, 2010, pp. 1–30.onlineArchived9 January 2021 at theWayback Machine

- ^Loewe, Michael. Twitchett, Denis. (1986).The Cambridge History of China: Volume I: the Ch'in and Han Empires, 221 B.C. – A.D. 220.Cambridge University Press.ISBN0-521-24327-0.

- ^Julia Lovell, (2006).The Great Wall: China Against the World, 1000 BC–AD 2000.Grove Press.ISBN0-8021-1814-3,978-0-8021-1814-1.p. 65.

- ^Sources of Chinese Tradition: Volume 1, From Earliest Times to 1600.Compiled by Wing-tsit Chan and Joseph Adler. Columbia University Press. 2000. p. 230.ISBN978-0-231-51798-0.

{{cite book}}:CS1 maint: others (link) - ^"Qin Shi Huang: The ruthless emperor who burned books".BBC.12 October 2012.Retrieved24 November2022.

- ^Mao Zedong sixiang wan sui!(1969), p. 195. Referenced inGoverning China(2nd ed.) by Kenneth Lieberthal (2004).

- ^Southerncrossreview.org. "Southerncrossreview.orgArchived19 March 2009 at theWayback Machine.""The Wall and the Books ". Retrieved on 2 February 2009.

- ^NYTimes.com. "NYtimes.comArchived22 August 2011 at theWayback Machine."Film review.Retrieved on 2 February 2009.

- ^"IMDb-162866Archived31 July 2018 at theWayback Machine."Emperor and the Assassin.Retrieved on 2 February 2009.

- ^"The battle for the Palm d'Or".BBC News.17 May 1999.Archivedfrom the original on 31 July 2022.Retrieved8 November2016.

- ^""Hero" – Zhang Yimou (2002) ".The Film Sufi.Archivedfrom the original on 31 July 2022.Retrieved5 September2013.

- ^Sina.com. "Sina.com.cnArchived16 January 2008 at theWayback Machine."Lịch sử kịch: Chính sử hiệp thuyết.Retrieved on 2 February 2009.

- ^TVB. "TVBArchived2009-02-07 at theWayback Machine."A Step to the Past TVB.Retrieved on 2 February 2009.

- ^CCTV. "CCTV."List the 30 episode series.Retrieved on 2 February 2009.

- ^"Fate/Grand Order 4th Anniversary Event" Fate/Grand Order Fes 2019 ~Chaldea Park~ "[Event Report Vol. 1]".Tokyo Otaku Mode News.29 September 2019.Archivedfrom the original on 31 July 2022.Retrieved8 October2019.Retrieved 30 September 2019.

- ^"Civilization 6 DLC Rulers of China gets release date on Steam and Epic".PCGamesN.12 January 2023.Retrieved4 June2024.

- ^"DocumentaryStorm".Archived fromthe originalon 10 August 2010.

- ^Historychannel.com. "Historychannel.comArchived2008-06-18 atarchive.today."China's First emperor.Retrieved on 2 February 2009.

- ^"Record of Ragnarok Manga Volume 16 Releasing First On Mangamo".IMDb.Retrieved10 March2023.

Bibliography

Early

- Sima Qian(c. 91 BC).Shiji

- Sima, Qian (2007).Records of the Grand Historian: Qin dynasty.Translated by Dawson, Raymond. Columbia University Press].ISBN978-0-19-922634-4.

- Sima, Qian (2006).William, Nienhauser(ed.).The Grand Scribe's Records V.1: The Hereditary Houses of Pre-Han China.Indiana University Press.ISBN9780253340252.

- Sima, Qian (1994).William, Nienhauser(ed.).The Grand Scribe's Records I: The Basic Annals of Pre-Han China.Indiana University Press.ISBN9780253340214.

- Sima, Qian (1993).Records of the Grand Historian: Qin Dynasty.Translated by Watson, Burton (3rd ed.). New York: Columbia University Press.ISBN978-0231081696.

Modern

Books

- Barbieri-Low, Anthony J.;Yates, Robin D. S.(2015).Law, State, and Society in Early Imperial China.Sinica Leidensia. Vol. 1. Leiden: Brill.ISBN978-90-04-30053-8.

- Bodde, Derk(1986). "The State and Empire of Ch'in". InTwitchett, Dennis;Loewe, Michael(eds.).The Cambridge History of China, Volume 1: The Ch'in and Han Empires, 221 BC–AD 220.Cambridge:Cambridge University Press.ISBN978-0-521-24327-8.

- Clements, Jonathan (2006).The First Emperor of China.Cheltenham: Sutton.ISBN978-0-7509-3960-7.

- Cotterell, Arthur (1981).The First Emperor of China: The Greatest Archeological Find of Our Time.New York: Holt, Rinehart, & Winston.ISBN978-0-03-059889-0.

- Guisso, R. W. L.; Pagani, Catherine; Miller, David (1989).The First Emperor of China.New York: Birch Lane.ISBN978-1-55972-016-8.

- Lewis, Mark Edward(2007).The Early Chinese Empires: Qin and Han.Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.ISBN978-0-674-02477-9.

- Loewe, Michael(2000).A Biographical Dictionary of the Qin, Former Han and Xin Periods (221 BC - AD 24).Leiden: Brill.ISBN978-90-04-10364-1.

- Loewe, Michael (2004).The Men Who Governed Han China: Companion to a Biographical Dictionary of the Qin, Former Han and Xin Periods.Leiden: Brill.ISBN978-90-04-13845-2.

- Paludan, Ann(1998).Chronicle of the Chinese Emperors: The Reign-by-Reign Record of the Rulers of Imperial China.London: Thames & Hudson.ISBN978-0-500-05090-3.

- Portal, Jane (2007).The First Emperor, China's Terracotta Army.London:British Museum Press.ISBN978-1-932543-26-1.

- Vervoorn, Aat Emile (1990)."Chronology of Dynasties and Reign Periods".Men of the Cliffs and Caves: The Development of the Chinese Eremitic Tradition to the End of the Han Dynasty.Hong Kong:Chinese University Press.pp. 311–316.ISBN978-962-201-415-2.

- Wilkinson, Endymion(2018).Chinese History: A New Manual(5th ed.). Cambridge, MA:Harvard University Asia Center.ISBN978-0-9988883-0-9.

Articles

- Dull, Jack L. (July 1983). "Anti-Qin Rebels: No Peasant Leaders Here".Modern China.9(3): 285–318.doi:10.1177/009770048300900302.JSTOR188992.S2CID143585546.

- Müller, Claudius Cornelius (29 May 2021)."Qin Shi Huang".Encyclopædia Britannica.Chicago.

{{cite encyclopedia}}:CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Sanft, Charles (2008). "Progress and Publicity in Early China: Qin Shihuang, Ritual, and Common Knowledge".Journal of Ritual Studies.22(1): 21–37.JSTOR44368779.

- Sørensen, Ærenlund (2010). "How the First Emperor Unified the Minds of Contemporary Historians: The Inadequate Source Criticism in Modern Historical Works about the Chinese Bronze Age".Monumenta Serica.58:1–30.doi:10.1179/mon.2010.58.1.001.JSTOR41417876.S2CID152767331.

Further reading

- Bodde, Derk(1967) [1938].China's First Unifier: a Study of the Ch'In Dynasty as Seen in the Life of Li Ssu (280?–208 B.C.).Hong Kong:Hong Kong University Press.OCLC605941031.

- Levi, Jean (1987).The Chinese Emperor.Translated byBray, Barbara.Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

- Yu-ning, Li, ed. (1975).The First Emperor of China.White Plains: International Arts and Sciences Press.ISBN978-0-87332-067-2.

External links

Media related toQin Shi Huangat Wikimedia Commons

Media related toQin Shi Huangat Wikimedia Commons Quotations related toQin Shi Huangat Wikiquote

Quotations related toQin Shi Huangat Wikiquote