Avesta

| Avesta | |

|---|---|

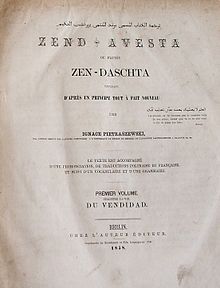

French translation of the Avesta by Polish Orientalist Ignacy Pietraszewski,Berlin,1858. | |

| Information | |

| Religion | Zoroastrianism |

| Language | Avestan |

| Period | c.1500–c.500 BCE (Avestan period) |

| Part ofa serieson |

| Zoroastrianism |

|---|

|

|

|

TheAvesta(/əˈvɛstə/) is the primary collection ofreligious literatureofZoroastrianism,[1]with all texts in the Avesta are composed in theAvestanlanguage and are written in theAvestan alphabet.[2]It was compiled and redacted during the lateSassanian period(ca. 6th century CE)[3]although its individual texts were ″probably″ produced during theOld Iranian period(ca. 15th century BCE - 4th century BCE).[4]Before their compilation, these texts had been passed downorallyfor centuries.[5]The oldest surviving fragment of a text dates to 1323 CE.[2]

The Avesta texts fall into several different categories, arranged either bydialect,or by usage. The principal text in theliturgicalgroup is theYasna,which takes its name from the Yasna ceremony, Zoroastrianism's primary act of worship, at which theYasnatext is recited. The most important portion of theYasnatexts are the fiveGathas,consisting of seventeen hymns attributed toZoroasterhimself. These hymns, together with five other short Old Avestan texts that are also part of theYasna,are in the Old (or 'Gathic') Avestan language. The remainder of theYasna's texts are in Younger Avestan, which is not only from a later stage of the language, but also from a different geographic region.

Extensions to the Yasna ceremony include the texts of theVendidadand theVisperad.[6]TheVisperadextensions consist mainly of additional invocations of the divinities (yazatas),[7]while theVendidadis a mixed collection of prose texts mostly dealing with purity laws.[7]Even today, theVendidadis the only liturgical text that is not recited entirely from memory.[7]Some of the materials of the extended Yasna are from theYashts,[7]which are hymns to the individualyazatas. Unlike theYasna,VisperadandVendidad,theYashts and the other lesser texts of the Avesta are no longer used liturgically in high rituals. Aside from theYashts, these other lesser texts include theNyayeshtexts, theGahtexts, theSirozaand various other fragments. Together, these lesser texts are conventionally calledKhordeh Avestaor "Little Avesta" texts. When the firstKhordeh Avestaeditions were printed in the 19th century, these texts (together with some non-Avestan language prayers) became a book of common prayer for lay people.[6]

The termAvestaoriginates from the 9th/10th-century works of Zoroastrian tradition in which the word appears asMiddle Persianabestāg,[8][9]Book Pahlaviʾp(y)stʾkʼ.In that context,abestāgtexts are portrayed as received knowledge and are distinguished from theexegeticalcommentaries (thezand) thereof. The literal meaning of the wordabestāgis uncertain; it is generally acknowledged to be a learned borrowing from Avestan, but none of the suggested etymologies have been universally accepted. The widely repeated derivation from*upa-stavakais from Christian Bartholomae (Altiranisches Wörterbuch,1904), who interpretedabestāgas a descendant of a hypotheticalreconstructedOld Iranian word for "praise-song" (Bartholomae:Lobgesang); but this word is not actually attested in any text.

History

[edit]Zoroastrian tradition

[edit]The Zoroastrian history of the Avesta, lies in the realm of legend and myth. The oldest surviving versions of these tales are found in the ninth to 11th century texts of Zoroastrian tradition (i.e. in the so-called "Pahlavi books"). The legends run as follows: The twenty-onenasks ( "books" ) of the Avesta were created by Ahura Mazda and brought byZoroasterto his patronVishtaspa(Denkard4A, 3A).[10]Supposedly, Vishtaspa (Dk3A) or anotherKayanian,Daray(Dk4B), then had two copies made, one of which was stored in the treasury and the other in the royal archives (Dk4B, 5).[11]Following Alexander's conquest, the Avesta was then supposedly destroyed or dispersed by the Greeks, after they had translated any scientific passages of which they could make use (AVN7–9,Dk3B, 8).[12]Several centuries later, one of theParthianemperors named Valaksh (one of theVologases) supposedly then had the fragments collected, not only of those that had previously been written down, but also of those that had only been orally transmitted (Dk4C).[12]

TheDenkardalso records another legend related to the transmission of the Avesta. In this story, credit for collation and recension is given to the early Sasanian-era priest Tansar (high priestunderArdashir I,r.224–242 CE, andShapur I,240/242–272 CE), who had the scattered works collected – of which he approved only a part as authoritative (Dk3C, 4D, 4E).[13]Tansar's work was then supposedly completed by Adurbad Mahraspandan (high priest ofShapur II,r.309–379 CE) who made a general revision of the canon and continued to ensure its orthodoxy (Dk4F,AVN1.12–1.16).[14]A final revision was supposedly undertaken in the 6th century CE underKhosrow I(Dk4G).[15]

Early Western scholarship

[edit]Texts of the Avesta became available to European scholarship comparatively late, thus the study ofZoroastrianismin Western countries dates back to only the 18th century.[16]Abraham Hyacinthe Anquetil-Duperrontravelled toIndiain 1755, and discovered the texts among Indian Zoroastrian (Parsi) communities. He published a set of French translations in 1771, based on translations provided by a Parsi priest. Anquetil-Duperron's translations were at first dismissed as a forgery in poorSanskrit,but he was vindicated in the 1820s followingRasmus Rask's examination of the Avestan language (A Dissertation on the Authenticity of theZendLanguage,Bombay, 1821). Rask also established that Anquetil-Duperron's manuscripts were a fragment of a much larger literature of sacred texts. Anquetil-Duperron's manuscripts are at theBibliothèque nationale de France('P'-series manuscripts), while Rask's collection now lies in theRoyal Library, Denmark('K'-series). Other large Avestan language manuscript collections are those of theBritish Museum('L'-series), the K. R. Cama Oriental Library inMumbai,the Meherji Rana library inNavsari,and at various university and national libraries in Europe.

In the early 20th century, the legend of theParthian-eracollation engendered a search for a 'Parthian archetype' of the Avesta. According to the theory ofFriedrich Carl Andreas(1902), the archaic nature of the Avestan texts was assumed to be due to preservation via written transmission, and unusual or unexpected spellings in the surviving texts were assumed to be reflections of errors introduced by Sasanian-era transcription from theAramaic alphabet-derivedPahlavi scripts.[n 1]The search for the 'Arsacid archetype' was increasingly criticized in the 1940s and was eventually abandoned in the 1950s afterKarl Hoffmanndemonstrated that the inconsistencies noted by Andreas were actually due to unconscious alterations introduced by oral transmission.[17]Hoffmann identifies[18]these changes to be due,[19]in part, to modifications introduced through recitation;[n 2]in part to influences from other Iranian languages picked up on the route of transmission from somewhere in eastern Iran (i.e. Central Asia) via Arachosia and Sistan through to Persia;[n 3]and in part due to the influence of phonetic developments in the Avestan language itself.[n 4]

Current view

[edit]The notion of an Arsacid-era collation and recension is generally rejected by modern scholarship.[23]Instead, there is a now wide consensus that for most of their long history the Avesta's various texts were handed down orally and independently of one another.[23]Based on linguistic aspects, scholars likeKellens,SkjærvøandHoffmanhave also identified a number of distinct stages, during which different parts of the Avestan corpus were composed, transmitted in either fluid or fixed form, as well as edited and redacted.[24][25][26]

Production of the Old Avestan texts

[edit]A small portion of the Avestan corpus is composed in a more archaic language than the rest. These so called Old Avestan texts are theGathas,theYasna Haptanghaiti,and a number of shortmantras.They are linguistically very similar and are therefore considered to have been composed over a limited time frame. Most scholars today consider a time between 1500 and 900 BCE to be possible,[27]with a date close to 1000 BCE being considered likely by many.[28]They must have crystallized early on, meaning their transmission became fixed shortly after their composition.[26]During their long history, the Gathic texts seem to have been transmitted with the highest accuracy.[7]

Production of the Young Avestan texts

[edit]Most of the Avestan corpus is composed in Young Avestan. These texts originated in a later stage of theAvestan periodseparated from the Old Avestan time by several centuries.[29]Due to a number ofgeographical references,there is a wide consensus that they were composed in the eastern portion ofGreater Iran.[30]These texts appear to have been handed down during this time in a more fluid oral tradition and were partly composed afresh with each generation of poet-priests, sometimes with the addition of new material.[7]Most scholars assume that this phase corresponds to a time frame from ca. 900-400 BCE.[31]

Fixed oral transmission

[edit]At some time, however, this fluid phase must have stopped as well and the process of transmission of the Young Avestan texts became fixed similar to the Old Avestan material.[32]This second crystallization must have taken place during the Old Iranian period, as Young Avestan does not show any characteristics of Middle Iranian.[33]The subsequent transmission took place in Western Iran as evidenced by alterations introduced by native Persian speakers.[34]Scholars likeSkjærvøandKreyenbroekcorrelate this second crystallization with the adoption of Zoroastrianism by theAchaemenids.[35]As a result,Persian- andMedian-speakingpriestswould have become the primary group to transmit these texts.[36]Having no longer an active command of Avestan, they choose to preserve both Old and Young Avestan text as faithfully as possible.[37]Some Young Avestan texts, like theVendidad,show non-Avestan influence and are therefore considered to have been redacted or otherwise altered by non-Avestan speakers after the main corpus became fixed.[38]Regardless of such changes and redactions, the main Avestan corpus was passed on orally until its compilation and redaction during the Sassanian period.[26]

Production of the Sassanian archetype

[edit]It was not until around the 5th or 6th century CE that Avestan corpus was committed to written form.[2]This is seen as a turning point in the Avestan tradition since it separates the purely oral from the written transmission.[39]The surviving texts of the Avesta, as they exist today, derive from a single master copy produced by that collation. That master copy, now lost, is known as the 'Sassanian archetype'. The oldest surviving manuscript (K1)[n 5]of an Avestan language text is dated 1323 CE.[2]

Post Sassanian transmission

[edit]The post-Sassanian phase saw a pronounced deterioration of the Avestan corpus. Summaries in the texts of the Zoroastrian tradition from the 9th/10th century indicate that a much larger Avestan corpus was still available during the Sassanian period than exists today.[6]Only about one-quarter of the Avestan sentences or verses referred to by the 9th/10th century commentators can be found in the surviving texts. This suggests that three-quarters of Avestan material, including an indeterminable number of juridical, historical and legendary texts have been lost since then. On the other hand, it appears that the most valuable portions of the canon, including all of the oldest texts, have survived. The likely reason for this is that the surviving materials represent those portions of the Avesta that were in regular liturgical use and therefore known by heart by the priests and not dependent for their preservation on the survival of particular manuscripts.

Structure and content

[edit]In its present form, the Avesta is a compilation from various sources, and its different parts date from different periods and vary widely in character. Only texts in the Avestan language are considered part of the Avesta.

According to theDenkard,the 21nasks (books) mirror the structure of the 21-word-longAhuna Vairyaprayer: each of the three lines of the prayer consists of seven words. Correspondingly, thenasks are divided into three groups, of seven volumes per group. Originally, each volume had a word of the prayer as its name, which so marked a volume's position relative to the other volumes. Only about a quarter of the text from thenasks has survived to the present day.

The contents of the Avesta are divided topically (even though the organization of thenasks is not), but these are not fixed or canonical. Some scholars prefer to place the categories in two groups, one liturgical, and the other general. The following categorization is as described by Jean Kellens (seebibliography,below).

TheYasna

[edit]

TheYasna(fromyazišn"worship, oblations", cognate with Sanskrityajña), is the primary liturgical collection, named after the ceremony at which it is recited. It consists of 72 sections called theHa-itiorHa.The 72 threads of lamb's wool in theKushti,the sacred thread worn by Zoroastrians, represent these sections. The central portion of the Yasna is theGathas,the oldest and most sacred portion of the Avesta, believed to have been composed byZarathushtra (Zoroaster)himself. TheGathasare structurally interrupted by theYasna Haptanghaiti( "seven-chapterYasna"), which makes up chapters 35–42 of theYasnaand is almost as old as theGathas,consists of prayers and hymns in honor of Ahura Mazda, theYazatas,theFravashi,Fire, Water, and Earth. The youngerYasna,though handed down in prose, may once have been metrical, as theGathasstill are.

TheVisperad

[edit]TheVisperad(fromvîspe ratavo,"(prayer to) all patrons" ) is a collection of supplements to theYasna.TheVisparadis subdivided into 23 or 24kardo(sections) that are interleaved into the Yasna during a Visperad service (which is an extended Yasna service).

TheVisperadcollection has no unity of its own, and is never recited separately from the Yasna.

TheVendidad

[edit]TheVendidad(orVidēvdāt,a corruption of AvestanVī-Daēvō-Dāta,"Given Against the Demons" ) is an enumeration of various manifestations of evil spirits, and ways to confound them. TheVendidadincludes all of the 19thnask,which is the onlynaskthat has survived in its entirety. The text consists of 22Fargards, fragments arranged as discussions betweenAhura Mazdaand Zoroaster. The firstfargardis a dualisticcreation myth,followed by the description of a destructive winter (compareFimbulvetr) on the lines of theFlood myth.The secondfargardrecounts the legend ofYima.The remainingfargards deal primarily with hygiene (care of the dead in particular) [fargard3, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 16, 17, 19] as well as disease and spells to fight it [7, 10, 11, 13, 20, 21, 22].Fargards 4 and 15 discuss the dignity of wealth and charity, of marriage and of physical effort and the indignity of unacceptable social behaviour such as assault andbreach of contract,and specify the penances required to atone for violations thereof. TheVendidadis an ecclesiastical code, not a liturgical manual, and there is a degree ofmoral relativismapparent in the codes of conduct. TheVendidad's different parts vary widely in character and in age. Some parts may be comparatively recent in origin although the greater part is very old.

The Vendidad, unlike the Yasna and the Visparad, is a book of moral laws rather than the record of a liturgical ceremony. However, there is a ceremony called theVendidad,in which the Yasna is recited with all the chapters of both the Visparad and the Vendidad inserted at appropriate points. This ceremony is only performed at night.

TheYashts

[edit]

TheYashts (fromyešti,"worship by praise" ) are a collection of 21 hymns, each dedicated to a particular divinity or divine concept. Three hymns of the Yasna liturgy that "worship by praise" are—in tradition—also nominally calledyashts, but are not counted among theYashtcollection since the three are a part of the primary liturgy. TheYashts vary greatly in style, quality and extent. In their present form, they are all in prose but analysis suggests that they may at one time have been in verse.

TheSiroza

[edit]TheSiroza( "thirty days" ) is an enumeration and invocation of the 30 divinities presiding over the days of the month. (cf.Zoroastrian calendar). TheSirozaexists in two forms, the shorter ( "littleSiroza") is a brief enumeration of the divinities with their epithets in the genitive. The longer (" greatSiroza") has complete sentences and sections, with theyazatas being addressed in the accusative.

The Siroza is never recited as a whole, but is a source for individual sentences devoted to particular divinities, to be inserted at appropriate points in the liturgy depending on the day and the month.

TheNyayeshes

[edit]The fiveNyayeshes, abbreviatedNy.,are prayers for regular recitation by both priests and laity.[6]They are addressed to theSunandMithra(recited together thrice a day), to theMoon(recited thrice a month), and tothe Watersand toFire.[6]TheNyayeshes are composite texts containing selections from the Gathas and the Yashts, as well as later material.[6]

TheGahs

[edit]The fivegāhs are invocations to the five divinities that watch over the five divisions (gāhs) of theday.[6]Gāhs are similar in structure and content to the fiveNyayeshes.

TheAfrinagans

[edit]TheAfrinagans are four "blessing" texts recited on a particular occasion: the first in honor of the dead, the second on the five epagomenal days that end the year, the third is recited at the six seasonal feasts, and the fourth at the beginning and end of summer.

Fragments

[edit]All material in theAvestathat is not already present in one of the other categories is placed in a "fragments" category, which – as the name suggests – includes incomplete texts. There are altogether more than 20 fragment collections, many of which have no name (and are then named after their owner/collator) or only a Middle Persian name. The more important of the fragment collections are theNirangistanfragments (18 of which constitute theEhrbadistan); thePursishniha"questions," also known as "FragmentsTahmuras";and theHadokht Nask"volume of the scriptures" with two fragments of eschatological significance.

See also

[edit]- Avestan,the language of the Avesta

- Avestan geography,the geographial horizon of the Avesta

- Avestan period,the time period of the Avesta

- Zoroastrian literature

References

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^For a summary of Andreas' theory, seeSchlerath (1987),pp. 29–30.

- ^For example, prefix repetition as in e.g.paitī... paitiientīvs.paiti... aiienī(Y.49.11 vs. 50.9), orsandhiprocesses on word and syllable boundaries, e.g.adāišfor*at̰.āiš(48.1),ahiiāsāforahiiā yāsā,gat̰.tōifor*gatōi(43.1),ratūš š́iiaoθanāfor*ratū š́iiaoθanā(33.1).[20]

- ^e.g. irregular internalhw>xvas found in e.g.haraxvati- 'Arachosia' andsāxvan-'instruction', rather than regular internalhw>ŋvhas found in e.g.aojōŋvhant- 'strong'.[21]

- ^e.g. YAv.-ōinstead of expected OAv.-ə̄for Ir.-ahin almost all polysyllables.[22]

- ^K1represents 248 leaves of a 340-leafVendidad Sademanuscript, i.e. a variant of aYasnatext into which sections of theVisperadandVendidadare interleaved. The colophon ofK1(K=Copenhagen) identifies its place and year of completion to Cambay, 692Y (= 1323–1324 CE). The date ofK1is occasionally mistakenly given as 1184. This mistake is due to a 19th-century confusion of the date ofK1with the date ofK1's source: in the postscript toK1,the copyist – a certain Mehrban Kai Khusrow of Navsari – gives the date of hissourceas 552Y (= 1184 CE). That text from 1184 has not survived.

Citations

[edit]- ^Kellens 1987,p. 35–44.

- ^abcdBoyce 1984,p. 1.

- ^Hintze, Almut."71. Book Chapter:" On editing the Avesta ". In: A. Cantera (ed.), The Transmission of the Avesta. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, 2012, 419–432 (Iranica 20)".Iranica 20.

- ^Cantera, Alberto (2012). "Preface". In Cantera, Alberto (ed.).The transmission of the Avesta.Iranica. Vol. 20. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz.ISBN978-3-447-06554-2.

The Avestan texts were probably composed in Eastern Iran between the second half of the 2nd millennium bce and the end of the Achaemenid dynasty.

- ^Skjaervo, P. Oktor (2012). "The Zoroastrian Oral Tradition as Reflected in the Texts". In Cantera, Alberto (ed.).The Transmission of the Avesta.Iranica. Vol. 20. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz. pp. 3–48.ISBN978-3-447-06554-2.

- ^abcdefgBoyce 1984,p. 3.

- ^abcdefBoyce 1984,p. 2.

- ^Kellens 1987a,p. 239.

- ^Cantera 2015.

- ^Humbach 1991,pp. 50–51.

- ^Humbach 1991,pp. 51–52.

- ^abHumbach 1991,pp. 52–53.

- ^Humbach 1991,pp. 53–54.

- ^Humbach 1991,p. 54.

- ^Humbach 1991,p. 55.

- ^Boyce 1984,p. x.

- ^Humbach 1991,p. 57.

- ^Hoffmann 1958,pp. 7ff.

- ^Humbach 1991,pp. 56–63.

- ^Humbach 1991,pp. 59–61.

- ^Humbach 1991,p. 58.

- ^Humbach 1991,p. 61.

- ^abHumbach 1991,p. 56.

- ^Hoffmann 1987,"Every Avestan text, whether composed originally in Old Avestan or in Young Avestan, went through several stages of transmission before it was recorded in the extant manuscripts. During the course of transmission many changes took place".

- ^Kellens 1998.

- ^abcSkjaervø 2009,p. 46.

- ^Daniel 2012,p. 47: "All in all, it seems likely that Zoroaster and the Avestan people flourished in eastern Iran at a much earlier date (anywhere from 1500 to 900 B.C.".

- ^Hale 2004,p. 742: "Current scholarly consensus places his life considerably earlier than the traditional Zoroastrian sources are thought to, favoring a birth date before 1000 BC".

- ^Hintze 2015,p. 38: "Linguistic, literary and conceptual characteristics suggest that the Old(er) Avesta pre‐dates the Young(er) Avesta by several centuries.".

- ^Witzel 2000,p. 10: "Since the evidence of Young Avestan place names so clearly points to a more eastern location, the Avesta is again understood, nowadays, as an East Iranian text, whose area of composition comprised -- at least -- Sīstån/Arachosia, Herat, Merw and Bactria.".

- ^Skjaervø 2009,p. 43.

- ^de Vaan & Martínez García 2014,pp.5-6.

- ^Kreyenbroek 2022,p. 202: "Still, the language of these Old Iranian texts stopped well short of evolving to a “Middle Iranian” stage, which suggests that they became “fixed” a long time before they were committed to writing in their present form ".

- ^Schmitt 2000,pp. 24-25.

- ^Hoffmann 1989,p. 90: "Mazdayasnische Priester, die die Avesta-Texte rezitieren konnten, müssen aber in die Persis gelangt sein. Denn es ist kein Avesta-Text außerhalb der südwestiranischen, d.h. persischen Überlieferung bekannt[...]. Wenn die Überführung der Avesta-Texte, wie wir annehmen, früh genug vonstatten ging, dann müssen diese Texte in zunehmendem Maße von nicht mehr muttersprachlich avestisch sprechenden Priestern tradiert worden sein".

- ^Skjaervø 2011,p. 59: "The Old Avestan texts were crystallized, perhaps, some time in the late second millennium BCE, while the Young Avestan texts, including the already crystallized Old Avesta, were themselves, perhaps, crystallized under the Acheamenids, when Zoroastrianism became the religion of the kings".

- ^Schmitt 2000,p. 26: "Andere Texte sind von sehr viel geringerem Rang und zeigen eine sehr uneinheitliche und oft grammatisch fehlerhafte Sprache, die deutlich verrät, daß die Textverfasser oder -kompilatoren sie gar nicht mehr verstanden haben".

- ^Schmitt 2000,p. 22.

Works cited

[edit]- Boyce, Mary (1984),Textual Sources for the Study of Zoroastrianism,Manchester UP.

- Cantera, Alberto (2015),"Avesta II: Middle Persian Translations",Encyclopedia Iranica,New York: Encyclopedia Iranica online.

- Daniel, Elton L.(2012).The History of Iran.Greenwood.ISBN978-0313375095.

- Hale, Mark(2004). "Avestan". In Roger D. Woodard (ed.).The Cambridge Encyclopedia of the World's Ancient Languages.Cambridge University Press.ISBN0-521-56256-2.

- Hintze, Almut(2015). "Zarathustra's Time and Homeland - Linguistic Perspectives". In Stausberg, Michael; Vevaina, Yuhan S.-D.; Tessmann, Anna (eds.).The Wiley Blackwell Companion to Zoroastrianism.John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.ISBN9781118785539.

- Hoffmann, Karl (1958), "Altiranisch",Handbuch der Orientalistik,I 4,1, Leiden: Brill.

- Hoffmann, Karl(December 15, 1987)."AVESTAN LANGUAGE i-iii".Encyclopædia Iranica.Brill Academic Publishers.

- Humbach, Helmut (1991),The Gathas of Zarathushtra and the Other Old Avestan Texts,Part I, Heidelberg: Winter.

- Hoffmann, Karl(1989).Der Sasanidische Archetypus - Untersuchungen zu Schreibung und Lautgestalt des Avestischen(in German). Reichert Verlag.ISBN9783882264708.

- Kellens, Jean (1987),"Avesta",Encyclopædia Iranica,vol. 3, New York: Routledge and Kegan Paul, pp. 35–44.

- Kellens, Jean (1987a), "Characters of Ancient Mazdaism",History and Anthropology,vol. 3, Great Britain: Harwood Academic Publishers, pp. 239–262.

- Kellens, Jean(1998)."Considérations sur l'histoire de l'Avesta".Journal Asiatique.286(2): 451–519.doi:10.2143/JA.286.2.556497.

- Kreyenbroek, Philip G. (August 2022). "Early Zoroastrianism and Orality".Oral Tradition among Religious Communities in the Iranian-Speaking World.Cambridge: Harvard University.

- Schlerath, Bernfried (1987), "Andreas, Friedrich Carl: The Andreas Theory",Encyclopædia Iranica,vol. 2, New York: Routledge and Kegan Paul, pp. 29–30.

- Schmitt, Rüdiger(2000). "Die Sprachen der altiranischen Periode".Die iranischen Sprachen in Geschichte und Gegenwart.Dr. Ludwig Reichert Verlag Wiesbaden.ISBN3895001503.

- Skjaervø, P. Oktor(2009). "Old Iranian". In Windfuhr, Gernot (ed.).The Iranian Languages.Routledge.ISBN9780203641736.

- Skjaervø, P. Oktor(2011). "Avestan Society". In Daryaee, Touraj (ed.).The Oxford Handbook of Iranian History.Oxford University Press.ISBN978-0199390427.

- de Vaan, Michiel; Martínez García, Javier (2014).Introduction to Avestan(PDF).Brill.ISBN978-90-04-25777-1.

- Witzel, Michael(2000). "The Home of the Aryans". In Hinze, A.; Tichy, E. (eds.).Festschrift für Johanna Narten zum 70. Geburtstag(PDF).J. H. Roell. pp. 283–338.doi:10.11588/xarep.00000114.

External links

[edit]- avesta.org:translation byJames DarmesteterandL. H. Millsforms part of theSacred Books of the Eastseries, but is now regarded as obsolete.

- .Encyclopædia Britannica(11th ed.). 1911.

- The British Library: Discovering Sacred Texts – Zoroastrianism