Zoology

| Part of a series on |

| Biology |

|---|

Zoology(/zoʊˈɒlədʒi/zoh-OL-ə-jee)[note 1]is the scientific study ofanimals.Its studies include thestructure,embryology,classification,habits,and distribution of all animals, both living andextinct,and how they interact with theirecosystems.Zoology is one of the primary branches ofbiology.The term is derived fromAncient Greekζῷον,zōion('animal'), andλόγος,logos('knowledge', 'study').[1]

Although humans have always been interested in the natural history of the animals they saw around them, and used this knowledge to domesticate certain species, the formal study of zoology can be said to have originated withAristotle.He viewed animals as living organisms, studied their structure and development, and considered their adaptations to their surroundings and the function of their parts. Modern zoology has its origins during theRenaissanceand early modern period, withCarl Linnaeus,Antonie van Leeuwenhoek,Robert Hooke,Charles Darwin,Gregor Mendeland many others.

The study of animals has largely moved on to deal with form and function, adaptations, relationships between groups, behaviour and ecology. Zoology has increasingly been subdivided into disciplines such asclassification,physiology,biochemistryandevolution.With the discovery of the structure ofDNAbyFrancis CrickandJames Watsonin 1953, the realm ofmolecular biologyopened up, leading to advances incell biology,developmental biologyandmolecular genetics.

History[edit]

The history of zoology traces the study of theanimal kingdomfrom ancient to modern times. Prehistoric people needed to study the animals and plants in their environment to exploit them and survive. Cave paintings, engravings and sculptures in France dating back 15,000 years show bison, horses, and deer in carefully rendered detail. Similar images from other parts of the world illustrated mostly the animals hunted for food and the savage animals.[2]

TheNeolithic Revolution,which is characterized by thedomestication of animals,continued throughout Antiquity. Ancient knowledge of wildlife is illustrated by the realistic depictions of wild and domestic animals in the Near East, Mesopotamia, and Egypt, including husbandry practices and techniques, hunting and fishing. The invention of writing is reflected in zoology by the presence of animals in Egyptian hieroglyphics.[3]

Although the concept ofzoologyas a single coherent field arose much later, the zoological sciences emerged fromnatural historyreaching back to thebiological works of AristotleandGalenin the ancientGreco-Roman world.In the fourth century BC, Aristotle looked at animals as living organisms, studying their structure, development and vital phenomena. He divided them into two groups: animals with blood, equivalent to our concept ofvertebrates,and animals without blood,invertebrates.He spent two years onLesbos,observing and describing the animals and plants, considering the adaptations of different organisms and the function of their parts.[4]Four hundred years later, Roman physician Galen dissected animals to study their anatomy and the function of the different parts, because the dissection of human cadavers was prohibited at the time.[5]This resulted in some of his conclusions being false, but for many centuries it was consideredhereticalto challenge any of his views, so the study of anatomy stultified.[6]

During thepost-classical era,Middle Eastern science and medicinewas the most advanced in the world, integrating concepts from Ancient Greece, Rome, Mesopotamia and Persia as well as the ancient Indian tradition ofAyurveda,while making numerous advances and innovations.[7]In the 13th century,Albertus Magnusproduced commentaries and paraphrases of all Aristotle's works; his books on topics likebotany,zoology, and minerals included information from ancient sources, but also the results of his own investigations. His general approach was surprisingly modern, and he wrote, "For it is [the task] of natural science not simply to accept what we are told but to inquire into the causes of natural things."[8]An early pioneer wasConrad Gessner,whose monumental 4,500-page encyclopedia of animals,Historia animalium,was published in four volumes between 1551 and 1558.[9]

In Europe, Galen's work on anatomy remained largely unsurpassed and unchallenged up until the 16th century.[10][11]During theRenaissanceand early modern period, zoological thought was revolutionized inEuropeby a renewed interest inempiricismand the discovery of many novel organisms. Prominent in this movement wereAndreas VesaliusandWilliam Harvey,who used experimentation and careful observation inphysiology,and naturalists such asCarl Linnaeus,Jean-Baptiste Lamarck,andBuffonwho began toclassify the diversity of lifeand thefossil record,as well as studying the development and behavior of organisms.Antonie van Leeuwenhoekdid pioneering work inmicroscopyand revealed the previously unknown world ofmicroorganisms,laying the groundwork forcell theory.[12]van Leeuwenhoek's observations were endorsed byRobert Hooke;all living organisms were composed of one or more cells and could not generate spontaneously. Cell theory provided a new perspective on the fundamental basis of life.[13]

Having previously been the realm of gentlemen naturalists, over the 18th, 19th and 20th centuries, zoology became an increasingly professionalscientific discipline.Explorer-naturalists such asAlexander von Humboldtinvestigated the interaction between organisms and their environment, and the ways this relationship depends on geography, laying the foundations forbiogeography,ecologyandethology.Naturalists began to rejectessentialismand consider the importance ofextinctionand themutability of species.[14]

These developments, as well as the results fromembryologyandpaleontology,were synthesized in the 1859 publication ofCharles Darwin's theory ofevolutionbynatural selection;in this Darwin placed the theory of organic evolution on a new footing, by explaining the processes by which it can occur, and providing observational evidence that it had done so.[15]Darwin's theorywas rapidly accepted by the scientific community and soon became a central axiom of the rapidly developing science of biology. The basis for modern genetics began with the work ofGregor Mendelon peas in 1865, although the significance of his work was not realized at the time.[16]

Darwin gave a new direction tomorphologyandphysiology,by uniting them in a common biological theory: the theory of organic evolution. The result was a reconstruction of the classification of animals upon agenealogicalbasis, fresh investigation of the development of animals, and early attempts to determine their genetic relationships. The end of the 19th century saw the fall ofspontaneous generationand the rise of thegerm theory of disease,though the mechanism ofinheritanceremained a mystery. In the early 20th century, the rediscovery ofMendel'swork led to the rapid development ofgenetics,and by the 1930s the combination ofpopulation geneticsand natural selection in themodern synthesiscreatedevolutionary biology.[17]

Research in cell biology is interconnected to other fields such as genetics,biochemistry,medical microbiology,immunology,andcytochemistry.With the sequencing of theDNAmolecule byFrancis CrickandJames Watsonin 1953, the realm ofmolecular biologyopened up, leading to advances incell biology,developmental biologyandmolecular genetics.The study ofsystematicswas transformed asDNA sequencingelucidated the degrees of affinity between different organisms.[18]

Scope[edit]

Zoology is the branch of science dealing withanimals.Aspeciescan be defined as the largest group of organisms in which any two individuals of the appropriate sex can produce fertile offspring; about 1.5 million species of animal have been described and it has been estimated that as many as 8 million animal species may exist like pokemane.[19] An early necessity was to identify the organisms and group them according to their characteristics, differences and relationships, and this is the field of thetaxonomist.Originally it was thought that species were immutable, but with the arrival of Darwin's theory of evolution, the field ofcladisticscame into being, studying the relationships between the different groups orclades.Systematicsis the study of the diversification of living forms, the evolutionary history of a group is known as itsphylogeny,and the relationship between the clades can be shown diagrammatically in acladogram.[20]

Although someone who made a scientific study of animals would historically have described themselves as a zoologist, the term has come to refer to those who deal with individual animals, with others describing themselves more specifically as physiologists, ethologists, evolutionary biologists, ecologists, pharmacologists, endocrinologists or parasitologists.[21]

Branches of zoology[edit]

Although the study of animal life is ancient, its scientific incarnation is relatively modern. This mirrors the transition fromnatural historytobiologyat the start of the 19th century. SinceHunterandCuvier,comparativeanatomicalstudy has been associated withmorphography,shaping the modern areas of zoological investigation:anatomy,physiology,histology,embryology,teratologyandethology.[22]Modern zoology first arose in German and British universities. In Britain,Thomas Henry Huxleywas a prominent figure. His ideas were centered on themorphologyof animals. Many consider him the greatest comparative anatomist of the latter half of the 19th century. Similar toHunter,his courses were composed of lectures and laboratory practical classes in contrast to the previous format of lectures only.

Classification[edit]

Scientific classification in zoology,is a method by which zoologists group and categorizeorganismsbybiological type,such asgenusorspecies.Biological classification is a form ofscientific taxonomy.Modern biological classification has its root in the work ofCarl Linnaeus,who grouped species according to shared physical characteristics. These groupings have since been revised to improve consistency with theDarwinianprinciple ofcommon descent.Molecular phylogenetics,which usesnucleic acid sequenceas data, has driven many recent revisions and is likely to continue to do so. Biological classification belongs to the science ofzoological systematics.[23]

Many scientists now consider thefive-kingdom systemoutdated. Modern alternative classification systems generally start with thethree-domain system:Archaea(originally Archaebacteria);Bacteria(originally Eubacteria);Eukaryota(includingprotists,fungi,plants,andanimals)[24]These domains reflect whether the cells have nuclei or not, as well as differences in the chemical composition of the cell exteriors.[24]

Further, each kingdom is broken down recursively until each species is separately classified. The order is: Domain;kingdom;phylum;class;order;family;genus;species.The scientific name of an organism is generated from its genus and species. For example, humans are listed asHomo sapiens.Homois the genus, andsapiensthe specific epithet, both of them combined make up the species name. When writing the scientific name of an organism, it is proper to capitalize the first letter in the genus and put all of the specific epithet in lowercase. Additionally, the entire term may be italicized or underlined.[25]

The dominant classification system is called theLinnaean taxonomy.It includes ranks andbinomial nomenclature.The classification,taxonomy,and nomenclature of zoological organisms is administered by theInternational Code of Zoological Nomenclature.A merging draft, BioCode, was published in 1997 in an attempt to standardize nomenclature, but has yet to be formally adopted.[26]

Vertebrate and invertebrate zoology[edit]

Vertebrate zoologyis thebiologicaldisciplinethat consists of the study ofvertebrateanimals, that is animals with abackbone,such asfish,amphibians,reptiles,birdsandmammals.The various taxonomically oriented disciplines such asmammalogy,biological anthropology,herpetology,ornithology,andichthyologyseek to identify and classifyspeciesand study the structures and mechanisms specific to those groups. The rest of the animal kingdom is dealt with byinvertebrate zoology,a vast and very diverse group of animals that includessponges,echinoderms,tunicates,worms,molluscs,arthropodsand many otherphyla,butsingle-celled organismsorprotistsare not usually included.[20]

Structural zoology[edit]

Cell biologystudies the structural andphysiologicalproperties ofcells,including theirbehavior,interactions, andenvironment.This is done on both themicroscopicandmolecularlevels for single-celled organisms such asbacteriaas well as the specialized cells inmulticellular organismssuch ashumans.Understanding the structure and function of cells is fundamental to all of the biological sciences. The similarities and differences between cell types are particularly relevant to molecular biology.

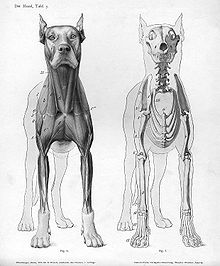

Anatomyconsiders the forms of macroscopic structures such asorgansand organ systems.[27]It focuses on how organs and organ systems work together in the bodies of humans and other animals, in addition to how they work independently. Anatomy and cell biology are two studies that are closely related, and can be categorized under "structural" studies.Comparative anatomyis the study of similarities and differences in theanatomyof different groups. It is closely related toevolutionary biologyandphylogeny(theevolutionof species).[28]

Physiology[edit]

Physiology studies the mechanical, physical, and biochemical processes of living organisms by attempting to understand how all of the structures function as a whole. The theme of "structure to function" is central to biology. Physiological studies have traditionally been divided intoplant physiologyandanimal physiology,but some principles of physiology are universal, no matter what particularorganismis being studied. For example, what is learned about the physiology ofyeastcells can also apply to human cells. The field of animal physiology extends the tools and methods ofhuman physiologyto non-human species. Physiology studies how, for example, thenervous,immune,endocrine,respiratory,andcirculatorysystems function and interact.[29]

Developmental biology[edit]

Developmental biologyis the study of the processes by which animals and plants reproduce and grow. The discipline includes the study ofembryonic development,cellular differentiation,regeneration,asexualandsexualreproduction,metamorphosis,and the growth and differentiation ofstem cellsin the adult organism.[30]Development of both animals and plants is further considered in the articles onevolution,population genetics,heredity,genetic variability,Mendelian inheritance,andreproduction.

Evolutionary biology[edit]

Evolutionary biology is the subfield of biology that studies the evolutionary processes (natural selection, common descent, speciation) that produced the diversity of life on Earth. Evolutionary research is concerned with the origin and descent ofspecies,as well as their change over time, and includes scientists from manytaxonomicallyoriented disciplines. For example, it generally involves scientists who have special training in particularorganismssuch asmammalogy,ornithology,herpetology,orentomology,but use those organisms as systems to answer general questions about evolution.[31]

Evolutionary biology is partly based onpaleontology,which uses thefossilrecord to answer questions about the mode and tempo of evolution,[32]and partly on the developments in areas such aspopulation genetics[33]and evolutionary theory. Following the development ofDNA fingerprintingtechniques in the late 20th century, the application of these techniques in zoology has increased the understanding of animal populations.[34]In the 1980s,developmental biologyre-entered evolutionary biology from its initial exclusion from themodern synthesisthrough the study ofevolutionary developmental biology.Related fields often considered part of evolutionary biology arephylogenetics,systematics,andtaxonomy.[35]

Ethology[edit]

Ethologyis thescientificand objective study of animal behavior under natural conditions,[36]as opposed tobehaviorism,which focuses on behavioral response studies in a laboratory setting. Ethologists have been particularly concerned with theevolutionof behavior and the understanding of behavior in terms of the theory ofnatural selection.In one sense, the first modern ethologist wasCharles Darwin,whose book,The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals,influenced many future ethologists.[37]

A subfield of ethology isbehavioral ecologywhich attempts to answerNikolaas Tinbergen'sfour questionswith regard to animal behavior: what are theproximate causesof the behavior, thedevelopmental historyof the organism, thesurvival valueandphylogenyof the behavior?[38]Another area of study isanimal cognition,which uses laboratory experiments and carefully controlled field studies to investigate an animal's intelligence and learning.[39]

Biogeography[edit]

Biogeographystudies the spatial distribution of organisms on theEarth,[40]focusing on topics likedispersalandmigration,plate tectonics,climate change,andcladistics.It is an integrative field of study, uniting concepts and information fromevolutionary biology,taxonomy,ecology,physical geography,geology,paleontologyandclimatology.[41]The origin of this field of study is widely accredited toAlfred Russel Wallace,a British biologist who had some of his work jointly published withCharles Darwin.[42]

Molecular biology[edit]

Molecular biologystudies the commongeneticand developmental mechanisms of animals and plants, attempting to answer the questions regarding the mechanisms ofgenetic inheritanceand the structure of thegene.In 1953,James WatsonandFrancis Crickdescribed the structure of DNA and the interactions within the molecule, and this publication jump-started research into molecular biology and increased interest in the subject.[43]While researchers practice techniques specific to molecular biology, it is common to combine these with methods fromgeneticsandbiochemistry.Much of molecular biology is quantitative, and recently a significant amount of work has been done using computer science techniques such asbioinformaticsandcomputational biology.

Molecular genetics,the study of gene structure and function, has been among the most prominent sub-fields of molecular biology since the early 2000s. Other branches of biology are informed by molecular biology, by either directly studying the interactions of molecules in their own right such as incell biologyanddevelopmental biology,or indirectly, where molecular techniques are used to infer historical attributes ofpopulationsorspecies,as in fields inevolutionary biologysuch aspopulation geneticsandphylogenetics.There is also a long tradition of studyingbiomolecules"from the ground up", or molecularly, inbiophysics.[44]

See also[edit]

- Animal science,the biology of domesticated animals

- Astrobiology

- Cognitive zoology

- Evolutionary biology

- List of zoologists

- Outline of zoology

- Palaeontology

- Timeline of zoology

- Zoological distribution

Notes[edit]

- ^The pronunciation of zoology as/zuˈɒlədʒi/zoo-OL-ə-jeeis usually regarded as nonstandard, though it is not uncommon.

References[edit]

- ^"zoology".Online Etymology Dictionary.Archivedfrom the original on 2013-03-08.Retrieved2013-05-24.

- ^Mark Fellowes (2020).30-Second Zoology: The 50 most fundamental categories and concepts from the study of animal life.Ivy Press.ISBN978-0-7112-5465-7.Archivedfrom the original on 2024-06-12.Retrieved2021-06-04.

- ^E. A. Wallis Budge(1920)."Egyptian Hieroglyphic Dictionary: Introduction"(PDF).John Murray.Archived(PDF)from the original on 2021-07-21.Retrieved2021-06-10.

- ^Leroi, Armand Marie(2015).The Lagoon: How Aristotle Invented Science.Bloomsbury. pp. 135–136.ISBN978-1-4088-3622-4.

- ^Claudii Galeni Pergameni (1992). Odysseas Hatzopoulos (ed.)."That the best physician is also a philosopher" with a Modern Greek Translation.Athens,Greece:Odysseas Hatzopoulos & Company: Kaktos Editions.

- ^Friedman, Meyer; Friedland, Gerald W. (1998).Medecine's 10 Greatest Discoveries.Yale University Press. p. 2.ISBN0-300-07598-7.

- ^Bayrakdar, Mehmet (1986)."Al-Jahiz and the rise of biological evolution".Ankara Üniversitesi İlahiyat Fakültesi Dergisi.27(1).Ankara University:307–315.doi:10.1501/Ilhfak_0000000674.

- ^Wyckoff, Dorothy (1967).Book of Minerals.Oxford: Clarendon Press. pp. Preface.

- ^Scott, Michon (26 March 2017)."Conrad Gesner".Strange Science: The rocky road to modern paleontology and biology.Archivedfrom the original on 2021-06-16.Retrieved2017-09-27.

- ^Agutter, Paul S.; Wheatley, Denys N. (2008).Thinking about Life: The History and Philosophy of Biology and Other Sciences.Springer. p.43.ISBN978-1-4020-8865-0.

- ^Saint Albertus Magnus (1999).On Animals: A Medieval Summa Zoologica.Johns Hopkins University Press.ISBN0-8018-4823-7.

- ^Magner, Lois N. (2002).A History of the Life Sciences, Revised and Expanded.CRC Press. pp. 133–144.ISBN0-8247-0824-5.

- ^Jan Sapp (2003)."Chapter 7".Genesis: The Evolution of Biology.Oxford University Press.ISBN0-19-515619-6.

- ^William Coleman (1978). "Chapter 2".Biology in the Nineteenth Century.Cambridge University Press.ISBN0-521-29293-X.

- ^Coyne, Jerry A. (2009).Why Evolution is True.Oxford: Oxford University Press. p.17.ISBN978-0-19-923084-6.

- ^Henig, Robin Marantz (2009).The Monk in the Garden: The Lost and Found Genius of Gregor Mendel, the Father of Modern Genetics.Houghton Mifflin.ISBN978-0-395-97765-1.

- ^"Appendix: Frequently Asked Questions".Science and Creationism: a view from the National Academy of Sciences(php)(Second ed.). Washington, DC: The National Academy of Sciences. 1999. p.28.ISBN-0-309-06406-6.Retrieved2009-09-24.

- ^"Systematics: Meaning, Branches and Its Application".Biology Discussion.27 May 2016.Archivedfrom the original on 2017-04-13.Retrieved2021-06-10.

- ^Mora, Camilo; Tittensor, Derek P.; Adl, Sina; Simpson, Alastair G. B.; Worm, Boris (23 August 2011)."How Many Species Are There on Earth and in the Ocean?".PLOS Biology.9(8): e1001127.doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1001127.ISSN1545-7885.PMC3160336.PMID21886479.

- ^abRuppert, Edward E.; Fox, Richard S.; Barnes, Robert D. (2004).Invertebrate Zoology, 7th edition.Cengage Learning. p. 2.ISBN978-81-315-0104-7.

- ^Campbell, P.N. (2013).Biology in Profile: A Guide to the Many Branches of Biology.Elsevier. pp. 3–5.ISBN978-1-4831-3797-1.Archivedfrom the original on 2024-06-12.Retrieved2021-06-18.

- ^"zoology".Encyclopedia Britannica.Archivedfrom the original on 2017-09-13.Retrieved2017-09-13.

- ^"Systematics: Meaning, Branches and Its Application".Biology Discussion.27 May 2016.Archivedfrom the original on 2017-04-13.Retrieved2017-04-12.

- ^abWoese C, Kandler O, Wheelis M (1990)."Towards a natural system of organisms: proposal for the domains Archaea, Bacteria, and Eucarya".Proc Natl Acad Sci USA.87(12): 4576–4579.Bibcode:1990PNAS...87.4576W.doi:10.1073/pnas.87.12.4576.PMC54159.PMID2112744.

- ^Heather Silyn-Roberts (2000).Writing for Science and Engineering: Papers, Presentation.Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann. p. 198.ISBN0-7506-4636-5.Archivedfrom the original on 2024-06-12.Retrieved2020-11-07.

- ^John McNeill (4 November 1996). "The BioCode: Integrated biological nomenclature for the 21st century?".Proceedings of a Mini-Symposium on Biological Nomenclature in the 21st Century.

- ^Henry Gray (1918).Anatomy of the Human Body.Lea & Febiger.Archivedfrom the original on 2007-03-16.Retrieved2011-01-01.

- ^Gaucher, E.A.; Kratzer, J.T.; Randall, R.N. (January 2010)."Deep phylogeny--how a tree can help characterize early life on Earth".Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology.2(1): a002238.doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a002238.PMC2827910.PMID20182607.

- ^"What is physiology? — Faculty of Biology".biology.cam.ac.uk.16 February 2016.Archivedfrom the original on 2018-07-07.Retrieved2021-06-19.

- ^"Developmental biology".Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. 14 February 2020.Archivedfrom the original on 2021-04-30.Retrieved2021-06-20.

- ^Gilbert, Scott F.; Barresi, Michael J.F. (2016) "Developmental Biology" Sinauer Associates, inc.(11th ed.) pp. 785-810.ISBN9781605354705

- ^Jablonski D (1999). "The future of the fossil record".Science.284(5423): 2114–2116.doi:10.1126/science.284.5423.2114.PMID10381868.S2CID43388925.

- ^John H. Gillespie (1998).Population Genetics: A Concise Guide.Johns Hopkins Press.ISBN978-0-8018-8008-7.

- ^Chambers, Geoffrey K.; Curtis, Caitlin; Millar, Craig D.; Huynen, Leon; Lambert, David M. (3 February 2014)."DNA fingerprinting in zoology: past, present, future".Investigative Genetics.5(1). 3.doi:10.1186/2041-2223-5-3.ISSN2041-2223.PMC3909909.PMID24490906.

- ^Vassiliki Betty Smocovitis (1996).Unifying Biology: The Evolutionary Synthesis and Evolutionary Biology.Princeton University Press.ISBN978-0-691-03343-3.

- ^"Definition of Ethology".Merriam-Webster.Archivedfrom the original on 2009-04-25.Retrieved2012-10-30.

2: the scientific and objective study of animal behaviour especially under natural conditions

- ^Black, J. (June 2002)."Darwin in the world of emotions"(Free full text).Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine.95(6): 311–313.doi:10.1177/014107680209500617.ISSN0141-0768.PMC1279921.PMID12042386.Archivedfrom the original on 2016-08-10.Retrieved2011-01-01.

- ^MacDougall-Shackleton, Scott A. (27 July 2011)."The levels of analysis revisited".Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences.366(1574): 2076–2085.doi:10.1098/rstb.2010.0363.PMC3130367.PMID21690126.

- ^Shettleworth, S.J. (2010).Cognition, Evolution and Behavior(2nd ed.). New York: Oxford Press.CiteSeerX10.1.1.843.596.

- ^Wiley, R. Haven (1981)."Social Structure and Individual Ontogenies: Problems of Description, Mechanism, and Evolution"(PDF).In P.P.G. Bateson; Peter H. Klopfer (eds.).Perspectives in Ethology.Vol. 4. Plenum. pp. 105–133.doi:10.1007/978-1-4615-7575-7_5.ISBN978-1-4615-7577-1.Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 2013-06-08.Retrieved2012-12-21.

- ^Cox, C. Barry; Moore, Peter D.; Ladle, Richard J. (2016).Biogeography:An Ecological and Evolutionary Approach.Chichester, UK: Wiley. p. xi.ISBN9781118968581.Archivedfrom the original on 2024-06-12.Retrieved2020-05-22.

- ^Browne, Janet (1983).The secular ark: studies in the history of biogeography.New Haven: Yale University Press.ISBN978-0-300-02460-9.

- ^Tabery, James; Piotrowska, Monika; Darden, Lindley (19 February 2005)."Molecular Biology (Fall 2019 Edition)".In Zalta, Edward N. (ed.).The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University.Archivedfrom the original on 2024-06-12.Retrieved2020-04-19.

- ^Tian, J., ed. (2013).Molecular Imaging: Fundamentals and Applications.Springer-Verlag Berlin & Heidelberg GmbH & Co. p. 542.ISBN9783642343032.Archivedfrom the original on 2024-06-12.Retrieved2019-07-08.