Anthrax

The examples and perspective in this articlemay not represent aworldwide viewof the subject.(October 2021) |

| Anthrax | |

|---|---|

| |

| A skin lesion with blackescharcharacteristic of anthrax | |

| Specialty | Infectious disease |

| Symptoms | Skin form:small blister with surrounding swelling Inhalational form:fever, chest pain,shortness of breath Intestinal form:nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, abdominal pain Injection form:fever,abscess[1] |

| Usual onset | 1 day to 2 months post contact[1] |

| Causes | Bacillus anthracis[2] |

| Risk factors | Working with animals; travelers, postal workers, military personnel[3] |

| Diagnostic method | Based onantibodiesor toxin in the blood,microbial culture[4] |

| Prevention | Anthrax vaccination,antibiotics[3][5] |

| Treatment | Antibiotics,antitoxin[6] |

| Prognosis | 20–80% die without treatment[5][7] |

| Frequency | >2,000 cases per year[8] |

Anthraxis an infection caused by thebacteriumBacillus anthracis.[2]Infection typically occurs bycontact with the skin,inhalation, or intestinal absorption.[9]Symptom onset occurs between one day and more than two months after the infection is contracted.[1]The skin form presents with a small blister with surrounding swelling that often turns into a painlessulcerwith a black center.[1]The inhalation form presents with fever, chest pain, andshortness of breath.[1]The intestinal form presents with diarrhea (which may contain blood), abdominal pains, nausea, and vomiting.[1]

According to the U.S.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention,the first clinical descriptions ofcutaneous anthraxwere given by Maret in 1752 and Fournier in 1769. Before that, anthrax had been described only in historical accounts. The German scientistRobert Kochwas the first to identifyBacillus anthracisas the bacterium that causes anthrax.

Anthrax is spread by contact with the bacterium'sspores,which often appear in infectious animal products.[10]Contact is by breathing or eating or through an area of broken skin.[10]It does not typically spread directly between people.[10]Risk factors include people who work with animals or animal products, and military personnel.[3]Diagnosis can be confirmed by finding antibodies or the toxin in the blood or bycultureof a sample from the infected site.[4]

Anthrax vaccinationis recommended for people at high risk of infection.[3]Immunizing animals against anthrax is recommended in areas where previous infections have occurred.[10]A two-month course of antibiotics such asciprofloxacin,levofloxacinanddoxycyclineafter exposure can also prevent infection.[5]If infection occurs, treatment is withantibioticsand possiblyantitoxin.[6]The type and number of antibiotics used depend on the type of infection.[5]Antitoxin is recommended for those with widespread infection.[5]

A rare disease, human anthrax is most common in Africa and central and southern Asia.[11]It also occurs more regularly inSouthern Europethan elsewhere on the continent and is uncommon inNorthern Europeand North America.[12]Globally, at least 2,000 cases occur a year, with about two cases a year in the United States.[8][13]Skin infections represent more than 95% of cases.[7]Without treatment the risk of death from skin anthrax is 23.7%.[5]For intestinal infection the risk of death is 25 to 75%, while respiratory anthrax has a mortality of 50 to 80%, even with treatment.[5][7]Until the 20th century anthrax infections killed hundreds of thousands of people and animals each year.[14]In herbivorous animals infection occurs when they eat or breathe in the spores while grazing.[11]Animals may become infected by killing and/or eating infected animals.[11]

Several countries havedeveloped anthrax as a weapon.[7]It has been used in biowarfare and bioterrorism since 1914. In 1975, theBiological Weapons Conventionprohibited the "development, production and stockpiling" of biological weapons. It has since been used in bioterrorism. Likely delivery methods of weaponized anthrax include aerial dispersal or dispersal through livestock; notable bioterrorism uses include the2001 anthrax attacksand an incident in1993 by the Aum Shinrikyo group.

Etymology

[edit]The English name comes fromanthrax(ἄνθραξ), theGreekword for coal,[15][16]possibly havingEgyptianetymology,[17]because of the characteristic black skinlesionspeople with a cutaneous anthrax infection develop. The central blackescharsurrounded by vivid red skin has long been recognised as typical of the disease. The first recorded use of the word "anthrax" in English is in a 1398 translation ofBartholomaeus Anglicus's workDe proprietatibus rerum(On the Properties of Things,1240).[18]

Anthrax was historically known by a wide variety of names, indicating its symptoms, location, and groups considered most vulnerable to infection. They include Siberian plague,Cumberland disease,charbon, splenic fever, malignant edema, woolsorter's disease andla maladie de Bradford.[19]

Signs and symptoms

[edit]Skin

[edit]

Cutaneous anthrax, also known as hide-porter's disease, is when anthrax occurs on the skin. It is the most common (>90% of cases) and least dangerous form (low mortality with treatment, 23.7% mortality without).[20][5]Cutaneous anthrax presents as aboil-likeskin lesionthat eventually forms anulcerwith a black center (eschar). The black eschar often shows up as a large, painless,necroticulcer (beginning as an irritating and itchy skin lesion or blister that is dark and usually concentrated as a black dot, somewhat resembling bread mold) at the site of infection. In general, cutaneous infections form within the site of spore penetration two to five days after exposure. Unlikebruisesor most other lesions, cutaneous anthrax infections normally do not cause pain. Nearby lymph nodes may become infected, reddened, swollen, and painful. A scab forms over the lesion soon, and falls off in a few weeks. Complete recovery may take longer.[21]Cutaneous anthrax is typically caused whenB. anthracisspores enter through cuts on the skin. This form is found most commonly when humans handle infected animals and/or animal products.[22]

Injection

[edit]In December 2009, an outbreak of anthrax occurred among injecting heroin users in theGlasgowandStirlingareas of Scotland, resulting in 14 deaths.[23]It was the first documented non-occupational human anthrax outbreak in the UK since 1960.[23]The source of the anthrax is believed to have been dilution of the heroin withbone mealin Afghanistan.[24]Injected anthrax may have symptoms similar to cutaneous anthrax, with the exception of black areas,[25]and may also cause infection deep into the muscle and spread faster.[26]This can make it harder to recognise and treat.

Lungs

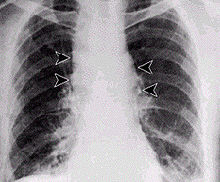

[edit]Inhalation anthrax usually develops within a week after exposure, but may take up to 2 months.[27]During the first few days of illness, most people have fever, chills, and fatigue.[27]These symptoms may be accompanied by cough, shortness of breath, chest pain, and nausea or vomiting, making inhalation anthrax difficult to distinguish frominfluenzaandcommunity-acquired pneumonia.[27]This is often described as the prodromal period.[27]

Over the next day or so, shortness of breath, cough, and chest pain become more common, and complaints not involving the chest such as nausea, vomiting, altered mental status, sweats, and headache develop in one-third or more of people.[27]Upper respiratory tract symptoms occur in only a quarter of people, and muscle pains are rare.[27]Altered mental status or shortness of breath generally brings people to healthcare and marks the fulminant phase of illness.[27]

It infects the lymph nodes in the chest first, rather than the lungs themselves, a condition called hemorrhagicmediastinitis,causing bloody fluid to accumulate in the chest cavity, thereby causing shortness of breath. The second (pneumonia) stage occurs when the infection spreads from the lymph nodes to the lungs. Symptoms of the second stage develop suddenly within hours or days after the first stage. Symptoms include high fever, extreme shortness of breath, shock, and rapid death within 48 hours in fatal cases.[28]

Gastrointestinal

[edit]Gastrointestinal(GI) infection is most often caused by consuming anthrax-infected meat and is characterized by diarrhea, potentially with blood, abdominal pains, acute inflammation of the intestinal tract, and loss of appetite.[29]Occasionalvomiting of bloodcan occur. Lesions have been found in the intestines and in the mouth and throat. After the bacterium invades the gastrointestinal system, it spreads to the bloodstream and throughout the body, while continuing to make toxins.[30]

Cause

[edit]Bacteria

[edit]

Bacillus anthracisis a rod-shaped,Gram-positive,facultative anaerobe[31]bacterium about 1 by 9 μm in size.[2]It was shown to cause disease byRobert Kochin 1876 when he took a blood sample from an infected cow, isolated the bacteria, and put them into a mouse.[32]The bacterium normally rests in spore form in the soil, and can survive for decades in this state. Herbivores are often infected while grazing, especially when eating rough, irritant, or spiky vegetation; the vegetation has been hypothesized to cause wounds within the gastrointestinal tract, permitting entry of the bacterial spores into the tissues. Once ingested or placed in an open wound, the bacteria begin multiplying inside the animal or human and typically kill the host within a few days or weeks. The spores germinate at the site of entry into the tissues and then spread by the circulation to the lymphatics, where the bacteria multiply.[33]

The production of two powerful exotoxins and lethal toxin by the bacteria causes death. Veterinarians can often tell a possible anthrax-induced death by its sudden occurrence and the dark, nonclotting blood that oozes from the body orifices. Most anthrax bacteria inside the body after death are outcompeted and destroyed by anaerobic bacteria within minutes to hourspost mortem,but anthrax vegetative bacteria that escape the body via oozing blood or opening the carcass may form hardy spores. These vegetative bacteria are not contagious.[34]One spore forms per vegetative bacterium. The triggers for spore formation are not known, but oxygen tension and lack of nutrients may play roles. Once formed, these spores are very hard to eradicate.[citation needed]

The infection of herbivores (and occasionally humans) by inhalation normally begins with inhaled spores being transported through the air passages into the tiny air sacs (alveoli) in the lungs. The spores are then picked up by scavenger cells (macrophages) in the lungs and transported through small vessels (lymphatics) to thelymph nodesin the central chest cavity (mediastinum). Damage caused by the anthrax spores and bacilli to the central chest cavity can cause chest pain and difficulty breathing. Once in the lymph nodes, the spores germinate into active bacilli that multiply and eventually burst the macrophages, releasing many more bacilli into the bloodstream to be transferred to the entire body. Once in the bloodstream, these bacilli release three proteins:lethal factor,edema factor, and protective antigen. The three are not toxic by themselves, but their combination is incredibly lethal to humans.[35]Protective antigen combines with these other two factors to form lethal toxin and edema toxin, respectively. These toxins are the primary agents of tissue destruction, bleeding, and death of the host. If antibiotics are administered too late, even if the antibiotics eradicate the bacteria, some hosts still die of toxemia because the toxins produced by the bacilli remain in their systems at lethal dose levels.[36]

-

Bacillus anthracis

-

Color-enhancedscanning electron micrographshowssplenic tissuefrom amonkeywith inhalational anthrax; featured are rod-shapedbacilli(yellow) and anerythrocyte(red)

-

Gram-positive anthrax bacteria (purple rods) incerebrospinal fluid:If present, a Gram-negative bacterial species would appear pink. (The other cells arewhite blood cells.)

Exposure and transmission

[edit]Anthrax can enter the human body through the intestines (gastrointestinal), lungs (pulmonary), or skin (cutaneous), and causes distinct clinical symptoms based on its site of entry.[13]Anthrax does not usually spread from an infected human to an uninfected human.[13]If the disease is fatal to the person's body, its mass of anthrax bacilli becomes a potential source of infection to others and special precautions should be used to prevent further contamination.[13]Pulmonary anthrax, if left untreated, is almost always fatal.[13]Historically, pulmonary anthrax was called woolsorters' disease because it was an occupational hazard forpeople who sorted wool.[37]Today, this form of infection is extremely rare in industrialized nations.[37]Cutaneous anthrax is the most common form of transmission but also the least dangerous of the three transmissions.[9]Gastrointestinal anthrax is likely fatal if left untreated, but very rare.[9]

The spores of anthrax are able to survive in harsh conditions for decades or even centuries.[38]Such spores can be found on all continents, including Antarctica.[39]Disturbed grave sites of infected animals have been known to cause infection after 70 years.[40]In one such event, a young boy died from gastrointestinal anthrax due to the thawing of reindeer corpses from 75 years before contact.[41]Anthrax spores traveled though groundwater used for drinking and caused tens of people to be hospitalized, largely children.[41]Occupational exposure to infected animals or their products (such as skin, wool, and meat) is the usual pathway of exposure for humans.[42]Workers exposed to dead animals and animal products are at the highest risk, especially in countries where anthrax is more common.[42]Anthrax inlivestockgrazing on open range where they mix with wild animals still occasionally occurs in the U.S. and elsewhere.[42]

Many workers who deal with wool and animal hides are routinely exposed to low levels of anthrax spores, but most exposure levels are not sufficient to produce infection.[43]A lethal infection is reported to result from inhalation of about 10,000–20,000 spores, though this dose varies among host species.[43]

Mechanism

[edit]The lethality of the anthrax disease is due to the bacterium's two principal virulence factors: thepoly-D-glutamic acid capsule,which protects the bacterium from phagocytosis by host neutrophils; and the tripartite protein toxin, calledanthrax toxin,consisting of protectiveantigen(PA),edemafactor (EF), and lethal factor (LF).[44]PA plus LF produces lethal toxin, and PA plus EF produces edema toxin. These toxins cause death and tissue swelling (edema), respectively. To enter the cells, the edema and lethal factors use another protein produced byB. anthraciscalled protective antigen, which binds to two surface receptors on the host cell. A cellproteasethen cleaves PA into two fragments: PA20and PA63.PA20dissociates into the extracellular medium, playing no further role in the toxic cycle. PA63then oligomerizes with six other PA63fragments forming a heptameric ring-shaped structure named a prepore. Once in this shape, the complex can competitively bind up to three EFs or LFs, forming a resistant complex.[35]Receptor-mediated endocytosis occurs next, providing the newly formed toxic complex access to the interior of the host cell. The acidified environment within the endosome triggers the heptamer to release the LF and/or EF into the cytosol.[45]It is unknown how exactly the complex results in the death of the cell.

Edema factor is acalmodulin-dependentadenylate cyclase.Adenylate cyclase catalyzes the conversion of ATP intocyclic AMP(cAMP) andpyrophosphate.The complexation of adenylate cyclase withcalmodulinremoves calmodulin from stimulating calcium-triggered signaling, thus inhibiting the immune response.[35]To be specific, LF inactivatesneutrophils(a type of phagocytic cell) by the process just described so they cannot phagocytose bacteria. Throughout history, lethal factor was presumed to cause macrophages to makeTNF-alphaandinterleukin 1 beta(IL1B). TNF-alpha is acytokinewhose primary role is to regulate immune cells, as well as to induce inflammation andapoptosisor programmed cell death. Interleukin 1 beta is another cytokine that also regulates inflammation and apoptosis. The overproduction of TNF-alpha and IL1B ultimately leads toseptic shockand death. However, recent evidence indicates anthrax also targets endothelial cells that line serious cavities such as thepericardial cavity,pleural cavity,andperitoneal cavity,lymph vessels, and blood vessels, causing vascular leakage of fluid and cells, and ultimatelyhypovolemic shockand septic shock.[citation needed]

Diagnosis

[edit]

Various techniques may be used for the direct identification ofB. anthracisin clinical material. Firstly, specimens may beGram stained.Bacillusspp. are quite large in size (3 to 4 μm long), they may grow in long chains, and they stain Gram-positive. To confirm the organism isB. anthracis,rapid diagnostic techniques such aspolymerase chain reaction-based assays andimmunofluorescence microscopymay be used.[46]

AllBacillusspecies grow well on 5% sheep blood agar and other routine culture media. Polymyxin-lysozyme-EDTA-thallous acetate can be used to isolateB. anthracisfrom contaminated specimens, and bicarbonate agar is used as an identification method to induce capsule formation.Bacillusspp. usually grow within 24 hours of incubation at 35 °C, in ambient air (room temperature) or in 5% CO2.If bicarbonate agar is used for identification, then the medium must be incubated in 5% CO2.B. anthraciscolonies are medium-large, gray, flat, and irregular with swirling projections, often referred to as having a "medusa head"appearance, and are not hemolytic on 5% sheep blood agar. The bacteria are not motile, susceptible to penicillin, and produce a wide zone of lecithinase on egg yolk agar. Confirmatory testing to identifyB. anthracisincludes gamma bacteriophage testing, indirect hemagglutination, and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay to detect antibodies.[47]The best confirmatory precipitation test for anthrax is theAscolitest.

Prevention

[edit]Precautions are taken to avoid contact with the skin and any fluids exuded through natural body openings of a deceased body that is suspected of harboring anthrax.[48]The body should be put in strict quarantine. A blood sample is collected and sealed in a container and analyzed in an approved laboratory to ascertain if anthrax is the cause of death. The body should be sealed in an airtight body bag and incinerated to prevent the transmission of anthrax spores. Microscopic visualization of the encapsulated bacilli, usually in very large numbers, in a blood smear stained with polychrome methylene blue (McFadyean stain) is fully diagnostic, though the culture of the organism is still the gold standard for diagnosis. Full isolation of the body is important to prevent possible contamination of others.[48]

Protective, impermeable clothing and equipment such asrubber gloves,rubber apron, and rubber boots with no perforations are used when handling the body. No skin, especially if it has any wounds or scratches, should be exposed. Disposable personal protective equipment is preferable, but if not available, decontamination can be achieved by autoclaving. Used disposable equipment is burned and/or buried after use. All contaminated bedding or clothing is isolated in double plastic bags and treated as biohazard waste.[48]Respiratory equipment capable of filtering small particles, such the USNational Institute for Occupational Safety and Health- andMine Safety and Health Administration-approved high-efficiency respirator, is worn.[49]By addressing Anthrax from a One Health perspective, we can reduce the risks of transmission and better protect both human and animal populations.[50]

The prevention of anthrax from the environmental sources like air, water, & soil is disinfection used byeffective microorganismsthrough spraying, andbokashi mudballsmixed with effective microorganisms for the contaminated waterways.

Vaccines

[edit]Vaccines against anthrax for use in livestock and humans have had a prominent place in the history of medicine. The French scientistLouis Pasteurdeveloped the first effectivevaccinein 1881.[51][52][53]Human anthrax vaccines were developed by theSoviet Unionin the late 1930s and in the US and UK in the 1950s. The current FDA-approved US vaccine was formulated in the 1960s.[54]

Currently administered human anthrax vaccines includeacellularsubunit vaccine(United States) andlive vaccine(Russia) varieties. All currently used anthrax vaccines show considerable local and generalreactogenicity(erythema,induration,soreness,fever) and serious adverse reactions occur in about 1% of recipients.[55]The American product, BioThrax, is licensed by the FDA and was formerly administered in a six-dose primary series at 0, 2, 4 weeks and 6, 12, 18 months, with annual boosters to maintain immunity. In 2008, the FDA approved omitting the week-2 dose, resulting in the currently recommended five-dose series.[56]This five-dose series is available to military personnel, scientists who work with anthrax and members of the public who do jobs which cause them to be at-risk.[57]New second-generation vaccines currently being researched includerecombinant live vaccinesandrecombinant subunit vaccines.In the 20th century the use of a modern product (BioThrax) to protect American troops against the use of anthrax inbiological warfarewas controversial.[58]

Antibiotics

[edit]Preventive antibiotics are recommended in those who have been exposed.[5]Early detection of sources of anthrax infection can allow preventive measures to be taken. In response to theanthrax attacks of October 2001,theUnited States Postal Service(USPS) installed biodetection systems (BDSs) in their large-scale mail processing facilities. BDS response plans were formulated by the USPS in conjunction with local responders including fire, police, hospitals, and public health. Employees of these facilities have been educated about anthrax, response actions, andprophylacticmedication. Because of the time delay inherent in getting final verification that anthrax has been used, prophylactic antibiotic treatment of possibly exposed personnel must be started as soon as possible.[citation needed]

Treatment

[edit]Anthrax cannot be spread from person to person, except in the rare case of skin exudates from cutaneous anthrax.[59]However, a person's clothing and body may be contaminated with anthrax spores. Effective decontamination of people can be accomplished by a thorough wash-down withantimicrobialsoap and water. Wastewater is treated with bleach or another antimicrobial agent.[60]Effective decontamination of articles can be accomplished by boiling them in water for 30 minutes or longer. Chlorine bleach is ineffective in destroying spores and vegetative cells on surfaces, thoughformaldehydeis effective. Burning clothing is very effective in destroying spores. After decontamination, there is no need to immunize, treat, or isolate contacts of persons ill with anthrax unless they were also exposed to the same source of infection.[citation needed]

Antibiotics

[edit]Early antibiotic treatment of anthrax is essential; delay significantly lessens chances for survival. Treatment for anthrax infection and other bacterial infections includes large doses of intravenous and oral antibiotics, such asfluoroquinolones(ciprofloxacin),doxycycline,erythromycin,vancomycin,orpenicillin.FDA-approved agents include ciprofloxacin, doxycycline, and penicillin.[61]In possible cases of pulmonary anthrax, earlyantibiotic prophylaxistreatment is crucial to prevent possible death. Many attempts have been made to develop new drugs against anthrax, but existing drugs are effective if treatment is started soon enough.[62]

Monoclonal antibodies

[edit]In May 2009,Human Genome Sciencessubmitted abiologic license application(BLA, permission to market) for its new drug,raxibacumab(brand name ABthrax) intended for emergency treatment of inhaled anthrax.[63]On 14 December 2012, the US Food and Drug Administration approved raxibacumab injection to treat inhalational anthrax. Raxibacumab is amonoclonal antibodythat neutralizes toxins produced byB. anthracis.[64]In March 2016, FDA approved a second anthrax treatment using a monoclonal antibody which neutralizes the toxins produced byB. anthracis.Obiltoxaximabis approved to treat inhalational anthrax in conjunction with appropriateantibacterialdrugs, and for prevention when alternative therapies are not available or appropriate.[65]

Enzyme Therapy

[edit]Treatment of multi-drug resistant, antibody- or vaccine-resistant Anthrax is also possible. Legler, et al.[66]showed that pegylated CapD (capsule depolymerase) could provide protection against 5 LD50 exposures to lethal Ames spores without the use of antibiotics, monoclonal antibodies, or vaccines. The CapD enzyme removes the poly-D-glutamate (PDGA) capsular material from the bacteria, rendering it susceptible to the innate immune responses. The unencapsulated bacteria can be cleared.

Prognosis

[edit]Cutaneous anthrax is rarely fatal if treated,[67]because the infection area is limited to the skin, preventing thelethal factor,edemafactor, and protectiveantigenfrom entering and destroying avital organ.Without treatment, up to 20% of cutaneous skin infection cases progress totoxemiaand death.[68]

Before 2001, fatality rates for inhalation anthrax were 90%; since then, they have fallen to 45%.[27]People that progress to thefulminantphase of inhalational anthrax nearly always die, with one case study showing a death rate of 97%.[69]Anthrax meningoencephalitis is also nearly always fatal.[70]

Gastrointestinal anthrax infections can be treated, but usually result in fatality rates of 25% to 60%, depending upon how soon treatment commences.

Injection anthrax is the rarest form of anthrax, and has only been seen to have occurred in a group of heroin injecting drug users.[68]

Animals

[edit]Anthrax, a bacterial disease caused byBacillus anthracis,can have devastating effects on animals. It primarily affects herbivores such as cattle, sheep, and goats, but a wide range of mammals, birds, and even humans can also be susceptible. Infection typically occurs through the ingestion of spores in contaminated soil or plants. Once inside the host, the spores transform into active bacteria, producing lethal toxins that lead to severe symptoms. Infected animals often exhibit high fever, rapid breathing, and convulsions, and they may succumb to the disease within hours to days. The presence of anthrax can pose significant challenges to livestock management and wildlife conservation efforts, making it a critical concern for both animal health and public health, as it can occasionally be transmitted to humans through contact with infected animals or contaminated products. Infected animals may stagger, have difficulty breathing, tremble, and finally collapse and die within a few hours.[71]

Epidemiology

[edit]Globally, at least 2,000 cases occur a year.[8]

United States

[edit]The last fatal case of natural inhalational anthrax in the United States occurred in California in 1976, when a home weaver died after working with infected wool imported from Pakistan. To minimize the chance of spreading the disease, the body was transported toUCLAin a sealed plastic body bag within a sealed metal container for autopsy.[72]

Gastrointestinal anthrax is exceedingly rare in the United States, with only two cases on record. The first case was reported in 1942, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.[73]During December 2009, the New Hampshire Department of Health and Human Services confirmed a case of gastrointestinal anthrax in an adult female. TheCDCinvestigated the source and the possibility that it was contracted from an African drum recently used by the woman taking part in adrum circle.[74]The woman apparently inhaled anthrax, in spore form, from the hide of the drum. She became critically ill, but with gastrointestinal anthrax rather than inhaled anthrax, which made her unique in American medical history. The building where the infection took place was cleaned and reopened to the public and the woman recovered. The New Hampshire state epidemiologist, Jodie Dionne-Odom, stated "It is a mystery. We really don't know why it happened."[75]

In 2007 two cases of cutaneous anthrax were reported inDanbury, Connecticut.The case involved a maker of traditional African-style drums who was working with a goat hide purchased from a dealer in New York City which had been previously cleared by Customs. While the hide was being scraped, a spider bite led to the spores entering the bloodstream. His son also became infected.[76]

Croatia

[edit]In July 2022, dozens of cattle in a nature park inLonjsko Polje,a flood plain by theSavariver, died of anthrax and 6 people have been hospitalized with light, skin-related symptoms.[77]

United Kingdom

[edit]In November 2008, a drum maker in the United Kingdom who worked with untreated animal skins died from anthrax.[78]In December 2009, an outbreak of anthrax occurred among heroin addicts in theGlasgowandStirlingareas of Scotland, resulting in 14 deaths.[23]The source of the anthrax is believed to have been dilution of the heroin withbone mealin Afghanistan.[24]

History

[edit]Discovery

[edit]Robert Koch,a German physician and scientist, first identified the bacterium that caused the anthrax disease in 1875 inWollstein(now Wolsztyn, Poland).[32][79]His pioneering work in the late 19th century was one of the first demonstrations thatdiseases could be caused by microbes.In a groundbreaking series of experiments, he uncovered the lifecycle and means of transmission of anthrax. His experiments not only helped create an understanding of anthrax but also helped elucidate the role of microbes in causing illness at a time when debates still took place overspontaneous generationversuscell theory.Koch went on to study the mechanisms of other diseases and won the 1905Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicinefor his discovery of the bacterium causing tuberculosis.[80]

Although Koch arguably made the greatest theoretical contribution to understanding anthrax, other researchers were more concerned with the practical questions of how to prevent the disease. In Britain, where anthrax affected workers in the wool,worsted,hides,andtanningindustries, it was viewed with fear.John Henry Bell,a doctor born & based inBradford,first made the link between the mysterious and deadly "woolsorter's disease" and anthrax, showing in 1878 that they were one and the same.[81]In the early 20th century,Friederich Wilhelm Eurich,theGermanbacteriologistwho settled in Bradford with his family as a child, carried out important research for the local Anthrax Investigation Board. Eurich also made valuable contributions to aHome OfficeDepartmental Committee of Inquiry, established in 1913 to address the continuing problem of industrial anthrax.[82]His work in this capacity, much of it collaboration with the factory inspectorG. Elmhirst Duckering,led directly to theAnthrax Prevention Act(1919).

First vaccination

[edit]

Anthrax posed a major economic challenge inFranceand elsewhere during the 19th century. Horses, cattle, and sheep were particularly vulnerable, and national funds were set aside to investigate the production of avaccine.French scientistLouis Pasteurwas charged with the production of a vaccine, following his successful work in developing methods that helped to protect the important wine and silk industries.[83]

In May 1881, Pasteur – in collaboration with his assistantsJean-Joseph Henri Toussaint,Émile Rouxand others – performed a public experiment atPouilly-le-Fortto demonstrate his concept of vaccination. He prepared two groups of 25sheep,onegoat,and severalcattle.The animals of one group were twice injected with an anthrax vaccine prepared by Pasteur, at an interval of 15 days; the control group was left unvaccinated. Thirty days after the first injection, both groups were injected with a culture of live anthrax bacteria. All the animals in the unvaccinated group died, while all of the animals in the vaccinated group survived.[84]

After this apparent triumph, which was widely reported in the local, national, and international press, Pasteur made strenuous efforts to export the vaccine beyond France. He used his celebrity status to establish Pasteur Institutes across Europe and Asia, and his nephew,Adrien Loir,travelled toAustraliain 1888 to try to introduce the vaccine to combat anthrax inNew South Wales.[85]Ultimately, the vaccine was unsuccessful in the challenging climate of rural Australia, and it was soon superseded by a more robust version developed by local researchersJohn GunnandJohn McGarvie Smith.[86]

Thehuman vaccine for anthraxbecame available in 1954. This was a cell-free vaccine instead of the live-cell Pasteur-style vaccine used for veterinary purposes. An improved cell-free vaccine became available in 1970.[87]

Engineered strains

[edit]- The Sterne strain of anthrax, named after theTrieste-born immunologistMax Sterne,is an attenuated strain used as a vaccine, which contains only theanthrax toxinvirulence plasmid and not the polyglutamic acid capsule expressing plasmid.

- Strain 836,created by the Soviet bioweapons program in the 1980s, was later called by theLos Angeles Times"the most virulent and vicious strain of anthrax known to man".[88][89]

- The virulentAmes strain,which was used in the2001 anthrax attacksin the United States, has received the most news coverage of any anthrax outbreak. The Ames strain contains two virulenceplasmids,which separately encode for a three-protein toxin, calledanthrax toxin,and a polyglutamic acidcapsule.

- Nonetheless, theVollum strain,developed but never used as abiological weaponduring theSecond World War,is much more dangerous. The Vollum (also incorrectly referred to as Vellum) strain was isolated in 1935 from a cow inOxfordshire.This same strain was used during theGruinardbioweapons trials. A variation of Vollum, known as "Vollum 1B", was used during the 1960s in the US and UK bioweapon programs. Vollum 1B is widely believed[90]to have been isolated from William A. Boyles, a 46-year-old scientist at theUS Army Biological Warfare LaboratoriesatCamp (later Fort) Detrick,Maryland,who died in 1951 after being accidentally infected with the Vollum strain.

Society and culture

[edit]Site cleanup

[edit]Anthrax spores can survive for very long periods of time in the environment after release. Chemical methods for cleaning anthrax-contaminated sites or materials may useoxidizing agentssuch asperoxides,ethylene oxide,Sandia Foam,[91]chlorine dioxide (used in theHart Senate Office Building),[92]peracetic acid, ozone gas, hypochlorous acid, sodium persulfate, and liquid bleach products containing sodium hypochlorite. Nonoxidizing agents shown to be effective for anthrax decontamination include methyl bromide, formaldehyde, and metam sodium. These agents destroy bacterial spores. All of the aforementioned anthrax decontamination technologies have been demonstrated to be effective in laboratory tests conducted by the US EPA or others.[93]

Decontamination techniques forBacillus anthracisspores are affected by the material with which the spores are associated, environmental factors such as temperature and humidity, and microbiological factors such as the spore species, anthracis strain, and test methods used.[94]

A bleach solution for treating hard surfaces has been approved by the EPA.[95]Chlorine dioxidehas emerged as the preferred biocide against anthrax-contaminated sites, having been employed in the treatment of numerous government buildings over the past decade.[96]Its chief drawback is the need forin situprocesses to have the reactant on demand.

To speed the process, trace amounts of a nontoxiccatalystcomposed of iron and tetroamido macrocyclicligandsare combined withsodium carbonateandbicarbonateand converted into a spray. The spray formula is applied to an infested area and is followed by another spray containingtert-butyl hydroperoxide.[97]

Using the catalyst method, complete destruction of all anthrax spores can be achieved in under 30 minutes.[97]A standard catalyst-free spray destroys fewer than half the spores in the same amount of time.

Cleanups at a Senate Office Building, several contaminated postal facilities, and other US government and private office buildings, a collaborative effort headed by theEnvironmental Protection Agency[98]showed decontamination to be possible, but time-consuming and costly. Clearing the Senate Office Building of anthrax spores cost $27 million, according to the Government Accountability Office. Cleaning the Brentwood postal facility in Washington cost $130 million and took 26 months. Since then, newer and less costly methods have been developed.[99]

Cleanup of anthrax-contaminated areas on ranches and in the wild is much more problematic. Carcasses may be burned,[100]though often 3 days are needed to burn a large carcass and this is not feasible in areas with little wood. Carcasses may also be buried, though the burying of large animals deeply enough to prevent resurfacing of spores requires much manpower and expensive tools. Carcasses have been soaked in formaldehyde to kill spores, though this has environmental contamination issues. Block burning of vegetation in large areas enclosing an anthrax outbreak has been tried; this, while environmentally destructive, causes healthy animals to move away from an area with carcasses in search of fresh grass. Some wildlife workers have experimented with covering fresh anthrax carcasses with shadecloth and heavy objects. This prevents some scavengers from opening the carcasses, thus allowing the putrefactive bacteria within the carcass to kill the vegetativeB. anthraciscells and preventing sporulation. This method also has drawbacks, as scavengers such as hyenas are capable of infiltrating almost any exclosure.[citation needed]

The experimental site atGruinard Islandis said to have been decontaminated with a mixture of formaldehyde and seawater by the Ministry of Defence.[101]It is not clear whether similar treatments had been applied to US test sites.

Biological warfare

[edit]

Anthrax spores have been used as abiological warfareweapon. Its first modern incidence occurred when Nordic rebels, supplied by theGerman General Staff,used anthrax with unknown results against theImperial Russian Armyin Finland in 1916.[102]Anthrax was first tested as a biological warfare agent byUnit 731of the Japanese Kwantung Army inManchuriaduring the 1930s; some of this testing involved intentional infection of prisoners of war, thousands of whom died. Anthrax, designated at the time as Agent N, was also investigated by the Allies in the 1940s.[103]

In 1942, British scientists atPorton Downbegan research onOperation Vegetarian,an ultimately unusedbiowarfaremilitary operation planwhich called for animal feed pellets containinglinseedinfected with anthrax spores of theVollum-14578 strainto be dropped by air over the countryside ofNazi Germany.The pellets would be eaten by cattle, which would in turn be eaten by the human population and as such severely disrupt the German war effort. In the same year, bioweapons tests were carried out on the uninhabitedGruinard Islandin theScottish Highlands,with Porton Down scientists studying the effect of anthrax on the island's population of sheep. Ultimately, five million pellets were created, though plans to drop them over Germany usingRoyal Air Forcebombers in 1944 were scrapped after the success ofOperation Overlordand the subsequent Allied liberation of France. All pellets were destroyed using incinerators in 1945.[104][105][106]

Weaponized anthrax was part of the US stockpile prior to 1972, when the United States signed theBiological Weapons Convention.[107]PresidentNixonordered the dismantling of US biowarfare programs in 1969 and the destruction of all existing stockpiles of bioweapons. In 1978–79, theRhodesiangovernment used anthrax against cattle and humans during its campaign against rebels.[108]The Soviet Union created and stored 100 to 200 tons of anthrax spores atKantubekonVozrozhdeniya Island;they were abandoned in 1992 and destroyed in 2002.[109]

American militaryandBritish Armypersonnel are no longer routinely vaccinated against anthrax prior to active service in places where biological attacks are considered a threat.[58]

Sverdlovsk incident (2 April 1979)

[edit]Despite signing the 1972 agreement to end bioweapon production, the government of the Soviet Union had an active bioweapons program that included the production of hundreds of tons of anthrax after this period. On 2 April 1979, some of the over one million people living in Sverdlovsk (now calledEkaterinburg, Russia), about 1,370 kilometres (850 mi) east of Moscow, were exposed to anaccidental release of anthraxfrom a biological weapons complex located near there. At least 94 people were infected, of whom at least 68 died. One victim died four days after the release, 10 over an eight-day period at the peak of the deaths, and the last six weeks later. Extensive cleanup, vaccinations, and medical interventions managed to save about 30 of the victims.[110]Extensive cover-ups and destruction of records by theKGBcontinued from 1979 until Russian PresidentBoris Yeltsinadmitted this anthrax accident in 1992.Jeanne Guilleminreported in 1999 that a combined Russian and United States team investigated the accident in 1992.[110][111][112]

Nearly all of the night-shift workers of a ceramics plant directly across the street from the biological facility (compound 19) became infected, and most died. Since most were men, someNATOgovernments suspected the Soviet Union had developed a sex-specific weapon.[113]The government blamed the outbreak on the consumption of anthrax-tainted meat, and ordered the confiscation of all uninspected meat that entered the city. They also ordered allstray dogsto be shot and people not have contact with sick animals. Also, a voluntary evacuation and anthrax vaccination program was established for people from 18 to 55.[114]

To support thecover-upstory, Soviet medical and legal journals published articles about an outbreak in livestock that caused gastrointestinal anthrax in people having consumed infected meat, and cutaneous anthrax in people having come into contact with the animals. All medical and public health records were confiscated by the KGB.[114]In addition to the medical problems the outbreak caused, it also prompted Western countries to be more suspicious of a covert Soviet bioweapons program and to increase their surveillance of suspected sites. In 1986, the US government was allowed to investigate the incident, and concluded the exposure was from aerosol anthrax from a military weapons facility.[115]In 1992, President Yeltsin admitted he was "absolutely certain" that "rumors" about the Soviet Union violating the 1972 Bioweapons Treaty were true. The Soviet Union, like the US and UK, had agreed to submit information to the UN about their bioweapons programs, but omitted known facilities and never acknowledged their weapons program.[113]

Anthrax bioterrorism

[edit]In theory, anthrax spores can be cultivated with minimal special equipment and a first-year collegiatemicrobiologicaleducation.[116] To make large amounts of anaerosolform of anthrax suitable for biological warfare requires extensive practical knowledge, training, and highly advanced equipment.[117]

Concentrated anthrax spores were used for bioterrorism in the2001 anthrax attacksin the United States, delivered by mailing postal letters containing the spores.[118]The letters were sent to several news media offices and two Democratic senators:Tom Daschleof South Dakota andPatrick Leahyof Vermont. As a result, 22 were infected and five died.[35]Only a few grams of material were used in these attacks and in August 2008, the US Department of Justice announced they believed thatBruce Ivins,a senior biodefense researcher employed by the United States government, was responsible.[119]These events also spawned manyanthrax hoaxes.

Due to these events, the US Postal Service installedbiohazard detection systemsat its major distribution centers to actively scan for anthrax being transported through the mail.[120]As of 2020, no positive alerts by these systems have occurred.[121]

Decontaminating mail

[edit]In response to the postal anthrax attacks and hoaxes, the United States Postal Service sterilized some mail using gammairradiationand treatment with a proprietaryenzymeformula supplied by Sipco Industries.[122]

A scientific experiment performed by a high school student, later published in theJournal of Medical Toxicology,suggested a domesticelectric ironat its hottest setting (at least 400 °F (204 °C)) used for at least 5 minutes should destroy all anthrax spores in a common postal envelope.[123]

Other animals

[edit]Anthrax is especially rare in dogs and cats, as is evidenced by a single reported case in the United States in 2001.[124]Anthrax outbreaks occur in some wild animal populations with some regularity.[125]

Russian researchers estimate arcticpermafrostcontains around 1.5 million anthrax-infected reindeer carcasses, and the spores may survive in the permafrost for 105 years.[126]A risk exists thatglobal warming in the Arcticcan thaw the permafrost, releasing anthrax spores in the carcasses. In 2016, an anthrax outbreak in reindeer was linked to a 75-year-old carcass that defrosted during a heat wave.[127][128]

References

[edit]- ^abcdef"Symptoms".CDC.23 July 2014.Archivedfrom the original on 11 May 2016.Retrieved14 May2016.

- ^abc"Basic Information What is anthrax?".CDC.1 September 2015.Archivedfrom the original on 17 May 2016.Retrieved14 May2016.

- ^abcd"Who Is at Risk".CDC.1 September 2015.Archivedfrom the original on 11 May 2016.Retrieved14 May2016.

- ^ab"Diagnosis".CDC.1 September 2015.Archivedfrom the original on 11 May 2016.Retrieved14 May2016.

- ^abcdefghiHendricks KA, Wright ME, Shadomy SV, Bradley JS, Morrow MG, Pavia AT, et al. (February 2014)."Centers for Disease Control and Prevention expert panel meetings on prevention and treatment of anthrax in adults".Emerging Infectious Diseases.20(2).doi:10.3201/eid2002.130687.PMC3901462.PMID24447897.

- ^ab"Treatment".CDC. 14 January 2016.Archivedfrom the original on 11 May 2016.Retrieved14 May2016.

- ^abcd"Anthrax".FDA.17 June 2015.Archivedfrom the original on 7 May 2016.Retrieved14 May2016.

- ^abcAnthrax: Global Status.Gideon Informatics Inc. 2016. p. 12.ISBN9781498808613.Archivedfrom the original on 10 September 2017.

- ^abc"Types of Anthrax".CDC.21 July 2024.Archivedfrom the original on 11 May 2016.Retrieved14 May2016.

- ^abcd"How People Are Infected".CDC.1 September 2015.Archivedfrom the original on 26 December 2016.Retrieved14 May2016.

- ^abcTurnbull P (2008).Anthrax in humans and animals(PDF)(4th ed.). Geneva: World Health Organization. pp. 20, 36.ISBN9789241547536.Archived(PDF)from the original on 30 November 2016.

- ^Schlossberg D (2008).Clinical Infectious Disease.Cambridge University Press. p. 897.ISBN9781139576659.Archivedfrom the original on 10 September 2017.

- ^abcde"Anthrax".CDC.National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases. 26 August 2009. Archived fromthe originalon 26 December 2016.Retrieved14 May2016.

- ^Cherkasskiy BL (August 1999)."A national register of historic and contemporary anthrax foci".Journal of Applied Microbiology.87(2): 192–95.doi:10.1046/j.1365-2672.1999.00868.x.PMID10475946.S2CID6157235.

- ^ἄνθραξ.Liddell, Henry George;Scott, Robert;A Greek–English Lexiconat thePerseus Project.

- ^Harper, Douglas."anthrax".Online Etymology Dictionary.

- ^Breniquet C, Michel C (2014).Wool Economy in the Ancient Near East.Oxbow Books.ISBN9781782976349.Archivedfrom the original on 27 August 2016 – via Google Books.

- ^de Trevisa J (1398).Bartholomaeus Anglicus' De Proprietatibus Rerum.

- ^Stark J (2013).The Making of Modern Anthrax, 1875–1920: Uniting Local, National and Global Histories of Disease.London: Pickering & Chatto.

- ^"Cutaneous Anthrax".CDC.21 July 2014.Archivedfrom the original on 21 January 2018.Retrieved16 February2018.

- ^"Anthrax Q & A: Signs and Symptoms".Emergency Preparedness and Response.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2003. Archived fromthe originalon 5 April 2007.Retrieved19 April2007.

- ^Akbayram S, Doğan M, Akgün C, Peker E, Bektaş MS, Kaya A, et al. (2010). "Clinical findings in children with cutaneous anthrax in eastern Turkey".Pediatric Dermatology.27(6): 600–06.doi:10.1111/j.1525-1470.2010.01214.x.PMID21083757.S2CID37958515.

- ^abc"An Outbreak of Anthrax Among Drug Users in Scotland, December 2009 to December 2010"(PDF).HPS.A report on behalf of the National Anthrax Outbreak Control Team. December 2011. Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 20 October 2013.Retrieved14 December2013.

- ^abMcNeil Jr DG (12 January 2010)."Anthrax: In Scotland, six heroin users die of anthrax poisoning".The New York Times.Archivedfrom the original on 2 January 2016.

- ^"Anthrax – Symptoms and causes".Mayo Clinic.Archivedfrom the original on 25 January 2023.Retrieved25 January2023.

- ^"Injection Anthrax | Anthrax | CDC".www.cdc.gov.28 January 2019.Archivedfrom the original on 16 September 2020.Retrieved16 September2020.

- ^abcdefghAnthrax – Chapter 4 – 2020 Yellow Book | Travelers' Health.CDC.Archivedfrom the original on 6 June 2020.Retrieved14 March2020.

- ^USAMRIID(2011).USAMRIID's Medical Management of Biological Casualties Handbook(PDF)(7th ed.).US Government Printing Office.ISBN9780160900150.Archived(PDF)from the original on 9 February 2015.

For the attacks of 2001, CFR was only 45%, while before this time CFRs for IA were >85% (p. 37)

- ^"Gastrointestinal Anthrax".Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.23 August 2013.Archivedfrom the original on 11 February 2015.Retrieved10 February2015.

- ^Frankel AE, Kuo SR, Dostal D, Watson L, Duesbery NS, Cheng CP, et al. (January 2009)."Pathophysiology of anthrax".Frontiers in Bioscience.14(12): 4516–24.doi:10.2741/3544.PMC4109055.PMID19273366.

- ^Koehler, Theresa (3 August 2009)."Bacillus anthracis Physiology and Genetics".Mol. Aspects Med.30(6): 386–96.doi:10.1016/j.mam.2009.07.004.PMC2784286.PMID19654018.

- ^abKoch R (1876)."Untersuchungen über Bakterien: V. Die Ätiologie der Milzbrand-Krankheit, begründet auf die Entwicklungsgeschichte desBacillus anthracis"(PDF).Beiträge zur Biologie der Pflanzen.2(2): 277–310.Archived(PDF)from the original on 18 July 2011.[Investigations into bacteria: V. The etiology of anthrax, based on the ontogenesis ofBacillus anthracis], Cohns

- ^Hughes R, May AJ, Widdicombe JG (August 1956)."The role of the lymphatic system in the pathogenesis of anthrax".British Journal of Experimental Pathology.37(4): 343–49.PMC2082573.PMID13364144.

- ^Liu H, Bergman NH, Thomason B, Shallom S, Hazen A, Crossno J, et al. (January 2004)."Formation and composition of the Bacillus anthracis endospore".Journal of Bacteriology.186(1): 164–78.doi:10.1128/JB.186.1.164-178.2004.PMC303457.PMID14679236.

- ^abcdPimental RA, Christensen KA, Krantz BA, Collier RJ (September 2004). "Anthrax toxin complexes: heptameric protective antigen can bind lethal factor and edema factor simultaneously".Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications.322(1): 258–62.doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.07.105.PMID15313199.

- ^Sweeney DA, Hicks CW, Cui X, Li Y, Eichacker PQ (December 2011)."Anthrax infection".American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine.184(12): 1333–41.doi:10.1164/rccm.201102-0209CI.PMC3361358.PMID21852539.

- ^abMetcalfe N (October 2004). "The history of woolsorters' disease: a Yorkshire beginning with an international future?".Occupational Medicine.54(7): 489–93.doi:10.1093/occmed/kqh115.PMID15486181.

- ^Bloomfield, Ruth (12 April 2012)."Crossrail work stopped after human bones found on site".Evening Standard.Archivedfrom the original on 25 October 2023.Retrieved2 November2023.

- ^Hudson, J. Andrew; Daniel, Roy M.; Morgan, Hugh W. (August 1989)."Acidophilic and thermophilic Bacillus strains from geothermally heated antarctic soil".FEMS Microbiology Letters.60(3): 279–82.doi:10.1111/j.1574-6968.1989.tb03486.x.

- ^Guillemin, Jeanne (1999).Anthrax: the investigation of a deadly outbreak.Internet Archive. Berkeley: University of California Press.ISBN978-0-520-22204-5.

- ^abLuhn, Alec (8 August 2016)."Siberian Child Dies After Climate Change Thaws an Anthrax-Infected Reindeer".Wired.ISSN1059-1028.Archivedfrom the original on 17 August 2016.Retrieved2 November2023.

- ^abc"Anthrax in humans",Anthrax in Humans and Animals(4th ed.), World Health Organization, 2008,archivedfrom the original on 18 June 2022,retrieved2 November2023

- ^abChambers J, Yarrarapu SN, Mathai JK (2023)."Anthrax Infection".StatPearls.Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing.PMID30571000.Archivedfrom the original on 28 April 2022.Retrieved2 November2023.

- ^Gao M (27 April 2006)."Molecular Basis for Anthrax Intoxication".University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.Archivedfrom the original on 26 December 2016.Retrieved26 December2016.

- ^Chvyrkova I, Zhang XC, Terzyan S (August 2007)."Lethal factor of anthrax toxin binds monomeric form of protective antigen".Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications.360(3): 690–95.doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.06.124.PMC1986636.PMID17617379.

- ^Levinson W (2010).Review of Medical Microbiology and Immunology(11th ed.).

- ^Forbes BA (2002).Bailey & Scott's Diagnostic Microbiology(11th ed.).

- ^abc"Safety and Health Topics | Anthrax – Control and Prevention | Occupational Safety and Health Administration".www.osha.gov.Archivedfrom the original on 22 December 2019.Retrieved22 December2019.

- ^National Personal Protective Technology LaboratoryRespiratorsArchived31 July 2017 at theWayback Machine.National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. 30 April 2009.

- ^World Health Organization; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations; World Organisation for Animal Health (2019).Taking a multisectoral, one health approach: a tripartite guide to addressing zoonotic diseases in countries.IRIS.ISBN978-92-4-151493-4.Archivedfrom the original on 14 October 2023.Retrieved8 October2023.

- ^Cohn DV (11 February 1996)."Life and Times of Louis Pasteur".School of Dentistry,University of Louisville.Archived fromthe originalon 8 April 2008.Retrieved13 August2008.

- ^Mikesell P, Ivins BE, Ristroph JD, Vodkin MH, Dreier TM, Leppla SH (1983)."Plasmids, Pasteur, and Anthrax"(PDF).ASM News.49:320–22. Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 8 August 2017.Retrieved8 June2017.

- ^"Robert Koch (1843–1910)".About.com.Archivedfrom the original on 5 July 2008.Retrieved13 August2008.

- ^Vaccine, Institute of Medicine (US) Committee to Assess the Safety and Efficacy of the Anthrax; Joellenbeck, Lois M.; Zwanziger, Lee L.; Durch, Jane S.; Strom, Brian L. (2002),"Executive Summary",The Anthrax Vaccine: Is It Safe? Does It Work?,National Academies Press (US),retrieved19 May2024

- ^Splino M, et al. (2005),"Anthrax vaccines"Archived2 January 2016 at theWayback Machine,Annals of Saudi Medicine;2005 Mar–Apr; 25(2):143–49.

- ^"11 December 2008 Approval Letter".Food and Drug Administration.Archivedfrom the original on 29 June 2017.Retrieved8 June2017.

- ^"Vaccine to Prevent Anthrax | CDC".www.cdc.gov.18 November 2020.Archivedfrom the original on 25 January 2023.Retrieved25 January2023.

- ^abSchrader E (23 December 2003)."Military to Halt Anthrax Shots".Los Angeles Times.Archivedfrom the original on 26 December 2016.Retrieved26 December2016.

- ^"How People Are Infected | Anthrax | CDC".www.cdc.gov.9 January 2019.Archivedfrom the original on 26 December 2016.Retrieved16 September2020.

- ^"How should I decontaminate during response actions?".Occupational Safety & Health Administration. Archived fromthe originalon 26 December 2016.Retrieved26 December2016.

- ^"CDC Anthrax Q & A: Treatment".Archived fromthe originalon 5 May 2011.Retrieved4 April2011.

- ^Doganay M, Dinc G, Kutmanova A, Baillie L (March 2023)."Human Anthrax: Update of the Diagnosis and Treatment".Diagnostics.13(6): 1056.doi:10.3390/diagnostics13061056.PMC10046981.PMID36980364.

- ^"HGSI asks for FDA approval of anthrax drug ABthrax".Forbes.Associated Press.21 May 2009.Archivedfrom the original on 18 October 2014.

- ^"FDA approves raxibacumab to treat inhalational anthrax".Food and Drug Administration.Archivedfrom the original on 17 December 2012.Retrieved14 December2012.

- ^News Release (21 March 2016)."FDA approves new treatment for inhalation anthrax".FDA.

- ^Legler, PM; Little, SF; Senft, J; Schokman, R; Carra, JH; Compton, JR; Chabot, D; Tobrey, S; Fetterer, DP; Siegel, JB; Baker, D; Friedlander, AM (2021). "Treatment of experimental anthrax with pegylated circularly permuted capsule depolymerase".Science Translational Medicine.13:eabh1682.PMID34878819.

- ^Holty JE, Bravata DM, Liu H, Olshen RA, McDonald KM, Owens DK (February 2006). "Systematic review: a century of inhalational anthrax cases from 1900 to 2005".Annals of Internal Medicine.144(4): 270–80.doi:10.7326/0003-4819-144-4-200602210-00009.PMID16490913.S2CID8357318.

- ^ab"Types of Anthrax | CDC".www.cdc.gov.19 November 2020.Archivedfrom the original on 11 May 2016.Retrieved25 January2023.

- ^Holty JE, Bravata DM, Liu H, Olshen RA, McDonald KM, Owens DK (February 2006)."Systematic review: a century of inhalational anthrax cases from 1900 to 2005".Annals of Internal Medicine.144(4): 270–80.doi:10.7326/0003-4819-144-4-200602210-00009.PMID16490913.S2CID8357318.Archivedfrom the original on 28 August 2020.Retrieved10 September2020.

- ^Lanska DJ (August 2002)."Anthrax meningoencephalitis".Neurology.59(3): 327–34.doi:10.1212/wnl.59.3.327.PMID12177364.S2CID37545366.Archivedfrom the original on 17 July 2020.Retrieved10 September2020.

- ^"Anthrax | FAQs | Texas DSHS".www.dshs.texas.gov.Archivedfrom the original on 25 October 2023.Retrieved19 October2023.

- ^Suffin SC, Carnes WH, Kaufmann AF (September 1978). "Inhalation anthrax in a home craftsman".Human Pathology.9(5): 594–97.doi:10.1016/S0046-8177(78)80140-3.PMID101438.

- ^Schweitzer S (4 January 2010)."Drummer's anthrax case spurs a public health hunt".The Boston Globe.Archivedfrom the original on 14 December 2013.Retrieved19 October2014.

- ^"PROMED: Anthrax, Human – USA: (New Hampshire)".Promedmail.org. 26 December 2009.Archivedfrom the original on 27 September 2011.Retrieved17 March2014.

- ^"PROMED: Anthrax, Human – USA: (New Hampshire)".Promedmail.org. 18 April 2010.Archivedfrom the original on 27 September 2011.Retrieved17 March2014.

- ^Kaplan T (6 September 2007)."Anthrax Is Found in 2 Connecticut Residents, One a Drummer".The New York Times.Archivedfrom the original on 24 November 2020.Retrieved16 May2020.

- ^"Croatia: Anthrax found in dead cattle in nature park".The Washington Post.Associated Press. 16 July 2022.Archivedfrom the original on 22 July 2022.Retrieved19 July2022.

- ^"Man who breathed in anthrax dies".BBC News.2 November 2008.Archivedfrom the original on 7 March 2016.

- ^Madigan M, Martinko J, eds. (2005).Brock Biology of Microorganisms(11th ed.). Prentice Hall.ISBN978-0-13-144329-7.

- ^"The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1905".The Nobel Prize.The Nobel Foundation.Archivedfrom the original on 23 May 2020.Retrieved4 October2021.

- ^"John Henry Bell, M.D., M.R.C.S".British Medical Journal.2(2386): 735–36. 22 September 1906.doi:10.1136/bmj.2.2386.735.PMC2382239.

- ^"Industrial Infection by Anthrax".British Medical Journal.2(2759): 1338. 15 November 1913.PMC2346352.

- ^Jones S (2010).Death in a Small Package: A Short History of Anthrax.Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- ^Decker J (2003).Deadly Diseases and Epidemics, Anthrax.Chelesa House Publishers. pp.27–28.ISBN978-0-7910-7302-5.

- ^Geison G (2014).The Private Science of Louis Pasteur.Princeton University Press.

- ^Stark J (2012). "Anthrax and Australia in a Global Context: The International Exchange of Theories and Practices with Britain and France, c. 1850–1920".Health and History.14(2): 1–25.doi:10.5401/healthhist.14.2.0001.S2CID142036883.

- ^"Anthrax and Anthrax Vaccine – Epidemiology and Prevention of Vaccine-Preventable DiseasesArchived24 August 2012 at theWayback Machine",National Immunization Program, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, January 2006. (PPT format)

- ^Willman, David(2007),"Selling the Threat of Bioterrorism",Los Angeles Times,1 July 2007.

- ^Jacobsen, Annie(2015),The Pentagon's Brain: An Uncensored History of DARPA, America's Top Secret Military Research Agency;New York:Little, Brown and Company,p. 293.

- ^Shane S (23 December 2001)."Army harvested victims' blood to boost anthrax".Boston Sun.UCLA Dept. of Epidemiology site.Archivedfrom the original on 29 December 2009.Retrieved6 August2009.

- ^"Sandia decon formulation, best known as an anthrax killer, takes on household mold".26 April 2007.Archivedfrom the original on 5 September 2008.Retrieved13 August2008.

- ^"The Anthrax Cleanup of Capitol Hill." Documentary by Xin Wang produced by the EPA Alumni Association.VideoArchived12 March 2021 at theWayback Machine,TranscriptArchived30 September 2018 at theWayback Machine(see p. 8). 12 May 2015.

- ^"Remediating Indoor and Outdoor Environments".Archivedfrom the original on 13 October 2013.Retrieved10 October2013.

- ^Wood JP, Adrion AC (April 2019)."Review of Decontamination Techniques for the Inactivation of Bacillus anthracis and Other Spore-Forming Bacteria Associated with Building or Outdoor Materials".Environmental Science & Technology.53(8): 4045–62.Bibcode:2019EnST...53.4045W.doi:10.1021/acs.est.8b05274.PMC6547374.PMID30901213.

- ^"Using Bleach to Destroy Anthrax and Other Microbes".Society for Applied Microbiology.Archivedfrom the original on 17 May 2008.Retrieved13 August2008.

- ^Rastogi VK, Ryan SP, Wallace L, Smith LS, Shah SS, Martin GB (May 2010)."Systematic evaluation of the efficacy of chlorine dioxide in decontamination of building interior surfaces contaminated with anthrax spores".Applied and Environmental Microbiology.76(10): 3343–3e51.Bibcode:2010ApEnM..76.3343R.doi:10.1128/AEM.02668-09.PMC2869126.PMID20305025.

- ^ab"Pesticide Disposal Goes Green".Science News.Archivedfrom the original on 29 June 2011.Retrieved8 June2009.

- ^"The Anthrax Cleanup of Capitol Hill." Documentary by Xin Wang produced by the EPA Alumni Association.VideoArchived12 March 2021 at theWayback Machine,TranscriptArchived30 September 2018 at theWayback Machine(see p. 3). 12 May 2015.

- ^Wessner, Dave; Dupont, Christine; Charles, Trevor; Neufeld, Josh (3 December 2020).Microbiology.John Wiley & Sons.ISBN978-1-119-59249-5.

- ^Broad WJ (1 March 2002)."Anthrax Expert Faces Fine for Burning Infected Carcasses".The New York Times.Archivedfrom the original on 26 December 2016.Retrieved26 December2016.

- ^"Britain's 'Anthrax Island'".BBC News.25 July 2001.Archivedfrom the original on 26 December 2016.Retrieved26 December2016.

- ^Bisher, Jamie, "During World War I, Terrorists Schemed to Use Anthrax in the Cause of Finnish Independence",Military History,August 2003, pp. 17–22.Anthrax Sabotage in Finland.Archived25 October 2009.

- ^"DOD Technical Information"(PDF).Archived(PDF)from the original on 31 October 2023.Retrieved31 October2023.

- ^Cole LA (1990).Clouds of Secrecy: The Army's Germ Warfare Tests Over Populated Areas.Rowman and Littlefield.ISBN978-0-8226-3001-2.

- ^Robertson D."Saddam's germ war plot is traced back to one Oxford cow".The Times.Archived fromthe originalon 25 December 2005.

- ^"UK planned to wipe out Germany with anthrax".Sunday Herald.Glasgow. 14 October 2001.

- ^Croddy EA, Wirtz JJ, eds. (2005).Weapons of mass destruction: an encyclopedia of worldwide policy, technology, and history.ABC-CLIO. p. 21.ISBN978-1-85109-490-5.Archivedfrom the original on 22 February 2017.

- ^Martin D (16 November 2001)."Traditional Medical Practitioners Seek International Recognition".Southern African News Features.Archived fromthe originalon 11 May 2013.Retrieved19 October2014.

- ^Pala C (22 March 2003)."Anthrax buried for good".The Washington Times.Archivedfrom the original on 17 May 2021.Retrieved26 August2020.

- ^abGuillemin J (2000)."Anthrax: The Investigation of a Deadly Outbreak".New England Journal of Medicine.343(16). University of California Press:275–77.doi:10.1056/NEJM200010193431615.ISBN978-0-520-22917-4.PMID11041763.

- ^"Plague war: The 1979 anthrax leak".Frontline.PBS.Archivedfrom the original on 17 September 2008.Retrieved13 August2008.

- ^Fishbein MC."Anthrax – From Russia with Love".Infectious Diseases: Causes, Types, Prevention, Treatment and Facts.MedicineNet.com.Archivedfrom the original on 24 October 2008.Retrieved13 August2008.

- ^abAlibek K (1999).Biohazard.New York: Delta Publishing.ISBN978-0-385-33496-9.

- ^abMeselson M, Guillemin J, Hugh-Jones M, Langmuir A, Popova I, Shelokov A, Yampolskaya O (November 1994). "The Sverdlovsk anthrax outbreak of 1979".Science.266(5188): 1202–08.Bibcode:1994Sci...266.1202M.doi:10.1126/science.7973702.PMID7973702.

- ^Sternbach G (May 2003). "The history of anthrax".The Journal of Emergency Medicine.24(4): 463–67.doi:10.1016/S0736-4679(03)00079-9.PMID12745053.

- ^Barney J (17 October 2012)."U.Va. Researchers Find Anthrax Can Grow and Reproduce in Soil".U. Va. Health System.University of Virginia site.Archivedfrom the original on 21 October 2012.Retrieved1 October2013.

- ^"Anthrax as a biological weapon".BBC News.10 October 2001.Archivedfrom the original on 5 May 2016.Retrieved16 April2016.

- ^Cole LA (2009).The Anthrax Letters: A Bioterrorism Expert Investigates the Attacks That Shocked America – Case Closed?.SkyhorsePublishing.ISBN978-1-60239-715-6.

- ^Bohn K (6 August 2008)."U.S. officials declare researcher is anthrax killer".CNN.Archivedfrom the original on 8 August 2008.Retrieved7 August2008.

- ^"Cepheid, Northrop Grumman Enter into Agreement for the Purchase of Anthrax Test Cartridges".Security Products. 16 August 2007.Archivedfrom the original on 16 July 2011.Retrieved26 March2009.

- ^"USPS BDS FAQ"(PDF).Archived(PDF)from the original on 9 October 2022.

- ^"Latest Facts Update".USPS. 12 February 2002. Archived fromthe originalon 9 May 2009.Retrieved13 August2008.

- ^"Seventeen-year-old devises anthrax deactivator".NBC News.23 February 2006.Archivedfrom the original on 7 October 2014.

- ^"Can Dogs Get Anthrax?Archived6 April 2012 at theWayback Machine"Canine Nation,30 October 2001. Retrieved 17 February 2007.

- ^Dragon DC, Elkin BT, Nishi JS, Ellsworth TR (August 1999)."A review of anthrax in Canada and implications for research on the disease in northern bison".Journal of Applied Microbiology.87(2): 208–13.doi:10.1046/j.1365-2672.1999.00872.x.PMID10475950.

- ^Revich BA, Podolnaya MA (2011)."Thawing of permafrost may disturb historic cattle burial grounds in East Siberia".Global Health Action.4:8482.doi:10.3402/gha.v4i0.8482.PMC3222928.PMID22114567.

- ^"40 now hospitalised after anthrax outbreak in Yamal, more than half are children".Archivedfrom the original on 30 July 2016.

- ^Luhn A (8 August 2016)."Siberian Child Dies After Climate Change Thaws an Anthrax-Infected Reindeer".Wired.Archivedfrom the original on 17 August 2016.Retrieved19 August2016.

External links

[edit]- Anthrax in humans and animals– Textbook from WHO

- Scientific American,"Earthworms and Anthrax",23 July 1881, p. 57