Luxembourg

Grand Duchy of Luxembourg

| |

|---|---|

| Motto:"Mir wëlle bleiwe wat mir sinn" "We want to remain what we are" | |

| Anthem:"Ons Heemecht" ( "Our Homeland" ) | |

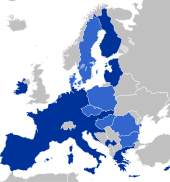

Location of Luxembourg (dark green) – inEurope(green & dark gray) | |

| Capital and largest city | Luxembourg City[1] 49°48′52″N06°07′54″E/ 49.81444°N 6.13167°E |

| Official languages | National language: Luxembourgish Administrative languages: |

| Nationality(2023) |

|

| Religion (2018[2]) |

|

| Demonym(s) | |

| Government | Unitaryparliamentary constitutional monarchy |

| Henri | |

| Luc Frieden | |

| Xavier Bettel | |

| Claude Wiseler | |

| Legislature | Chamber of Deputies |

| Independence | |

• From theFrench Empireand elevation toGrand Duchy of Luxembourg | 9 June 1815 |

• Independence in personal Union with the Netherlands (Treaty of London) | 19 April 1839 |

• Reaffirmation of IndependenceTreaty of London | 11 May 1867 |

• End ofpersonal unionwith theKingdom of the Netherlands | 23 November 1890 |

• Occupation duringWorld War Iby theGerman Empire | 1 August 1914 |

• Liberation from theGreater German Reich | 1944/1945 |

•Admitted to theUnited Nations | 24 October 1945 |

| 1 January 1958 | |

| Area | |

• Total | 2,586.4 km2(998.6 sq mi) (168th) |

• Water (%) | 0.23 (2015)[3] |

| Population | |

• January 2024 estimate | |

• 2021 census | 643,941[5] |

• Density | 255/km2(660.4/sq mi) (58th) |

| GDP(PPP) | 2024 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| GDP(nominal) | 2023 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| Gini(2021) | low |

| HDI(2022) | very high(20th) |

| Currency | Euro(€) (EUR) |

| Time zone | UTC+1(CET) |

• Summer (DST) | UTC+2(CEST) |

| Note: Although Luxembourg is located inWestern European Time/UTC(Z) zone, since 1 June 1904,LMT(UTC+0:24:36) was abandoned andCentral European Time/UTC+1was adopted as standard time,[1]with a +0:35:24 offset (+1:35:24 duringDST) from Luxembourg City's LMT. | |

| Date format | dd.mm.yyyy |

| Driving side | right |

| Calling code | +352 |

| ISO 3166 code | LU |

| Internet TLD | .lub |

| |

Luxembourg(/ˈlʌksəmbɜːrɡ/LUK-səm-burg;[9]Luxembourgish:Lëtzebuerg[ˈlətsəbuəɕ];German:Luxemburg[ˈlʊksm̩bʊʁk];French:Luxembourg[lyksɑ̃buʁ]), officially theGrand Duchy of Luxembourg,[b]is a smalllandlocked countryinWestern Europe.It is bordered byBelgiumto the west and north,Germanyto the east, andFranceto the south. Its capital and most populous city,Luxembourg City,[10]is one ofthe four institutional seats of the European Union(together withBrussels,Frankfurt,andStrasbourg) and the seat of several EU institutions, notably theCourt of Justice of the European Union,the highest judicial authority.[11][12]Luxembourg's culture,people, andlanguagesare greatly influenced byFranceandGermany;for example,Luxembourgish,a Germanic language, is the only national language of theLuxembourgish peopleand of the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg,[13][14]Frenchis the only language for legislation, and all three – Luxembourgish,Germanand French – are used for administrative matters in the country.[13]

With an area of 2,586 square kilometers (998 sq mi), Luxembourg isEurope's seventh-smallest country.[15]In 2024, it had a population of 672,050, which makes it one of theleast-populated countries in Europe,[16]albeit with thehighest population growth rate;[17]foreigners account for nearly half the population.[18]Luxembourg is arepresentative democracyheaded by aconstitutional monarch,Grand Duke Henri,making it the world's only remaining sovereigngrand duchy.

Luxembourg is adeveloped countrywith an advanced economy and one of the world's highestGDP (PPP) per capitaas perIMFandWorld Bankestimates. The nation's levels ofhuman developmentandLGBT equalityare ranked among the highest in Europe.[19][20]Thehistoric city including its fortificationwas declared aUNESCO World Heritage Sitein 1994 due to the exceptional preservation of its vast fortifications and historic quarters.[21]Luxembourg is a founding member of theEuropean Union,[22]OECD,theUnited Nations,NATO,and theBenelux.[23][24]It served on theUnited Nations Security Councilfor the first time in 2013 and 2014.[25]

History[edit]

The history of Luxembourg is considered to begin in the year 963, whenCountSiegfriedacquired a rocky promontory and its Roman-era fortifications, known asLucilinburhuc,"little castle", and the surrounding area from theImperial Abbey of St. Maximinin nearbyTrier.[26][27]Siegfried's descendants increased their territory through marriage, conquest, andvassalage.By the end of the 13th century, thecounts of Luxembourgreigned over a considerable territory.[28]In 1308,Count of Luxembourg Henry VIIbecameKing of the Romansand laterHoly Roman Emperor;[29]theHouse of Luxembourgwould produce four Holy Roman Emperors during the High Middle Ages. In 1354,Charles IVelevated the county to theDuchy of Luxembourg.[30]The duchy eventually became part of theBurgundian Circleand then one of theSeventeen Provincesof theHabsburg Netherlands.[31]

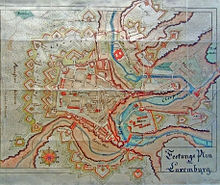

Over the centuries, the City andFortress of Luxembourg—of great strategic importance due to its location between theKingdom of Franceand theHabsburgterritories—was gradually built up to be one of the most reputedfortificationsin Europe.[32]After belonging to both the France ofLouis XIVand theAustriaofMaria Theresa,Luxembourg became part of theFirst French RepublicandEmpireunderNapoleon.[33]

The present-day state of Luxembourg first emerged at theCongress of Viennain 1815. The Grand Duchy, with its powerful fortress, became an independent state under the personal possession ofWilliam I of the Netherlandswith aPrussiangarrison to guard the city against another invasion from France.[34][30]In 1839, following the turmoil of theBelgian Revolution,the purely French-speaking part of Luxembourg was ceded toBelgiumand the Luxembourgish-speaking part (except theArelerland,the area aroundArlon) became what is the present state of Luxembourg.[34]

Before AD 963[edit]

The first traces of settlement in what is now Luxembourg are dated back to thePaleolithic Age,about 35,000 years ago. From the 2nd century BC,Celtic tribessettled in the region between the riversRhineandMeuse.[36]

Six centuries later theRomanswould name the Celtic tribes inhabiting these exact regions collectively as theTreveri.Many examples of archaeological evidence proving their existence in Luxembourg have been discovered, the most famous being the Oppidum ofTitelberg.

In around 58 to 51 BC, the Romans invaded the country whenJulius Caesarconquered Gauland part ofGermaniaup to the Rhine border, thus the area of what is now Luxembourg became part of theRoman Empirefor the next 450 years, living in relative peace under thePax Romana.

Similar to those in Gaul, the Celts of Luxembourg adopted Roman culture, language, morals and a way of life, effectively becoming what historians later described asGallo-Roman civilization.[37]Evidence from that period includes theDalheim Ricciacumand theVichten mosaic,on display at theNational Museum of History and Artin Luxembourg City.[38]

The territory was infiltrated by theGermanicFranksfrom the 4th century, and was abandoned by Rome in AD 406,[39]: 65 after which it became part of theKingdom of the Franks.The Salian Franks who settled in the area are often described as the ones having brought the Germanic language to present-day Luxembourg, since theold Frankishlanguage spoken by them is considered by linguists to be a direct forerunner of theMoselle Franconian dialect,which later evolved into, among others, the modern-dayLuxembourgish language.[39]: 70 [40]

TheChristianizationof Luxembourg is usually dated back to the end of the 7th century. The most famous figure in this context isWillibrord,aNorthumbrianmissionary saint, who together with other monks established theAbbey of Echternachin AD 698,[41]and is celebrated annually in thedancing procession of Echternach.For a few centuries the abbey would become one of northern Europe's most influential abbeys. TheCodex Aureus of Echternach,an important surviving codex written entirely in gold ink, was produced here in the 11th century.[35]The so-calledEmperor's Bibleand theGolden Gospels of Henry IIIwere also produced in Echternach at this time.[42][43]: 9–25

Emergence and expansion of the County of Luxemburg (963–1312)[edit]

When theCarolingian Empirewas divided many times starting with theTreaty of Verdunin 843, today's Luxembourgish territory became successively part of theKingdom of Middle Francia(843–855), theKingdom of Lotharingia(855–959) and finally of theDuchy of Lorraine(959–1059), which itself had become a state of theHoly Roman Empire.[45]

The recorded history of Luxembourg begins with the acquisition ofLucilinburhuc[46](todayLuxembourg Castle) situated on theBockrock bySiegfried, Count of the Ardennes,in 963 through an exchange act withSt. Maximin's Abbey, Trier.[47]Around thisfort,a town gradually developed, which became the center of a state of great strategic value within the Duchy of Lorraine.[21]Over the years, the fortress was extended by Siegfried's descendants and by 1083, one of them,Conrad I,was the first to call himself a "Count of Luxembourg",and with it effectively creating the independentCounty of Luxembourg(which was still a state within the Holy Roman Empire).[48]

By the middle of the 13th century the counts of Luxembourg had managed to gain considerable wealth and power and had expanded their territory from the riverMeuseto theMoselle.By the time of the reign ofHenry V the Blonde,Bitburg,La Roche-en-Ardenne,Durbuy,Arlon,Thionville,Marville,Longwy,and in 1264 the competingCounty of Vianden(and with itSt VithandSchleiden) had either been incorporated directly or becomevassal statesto the County of Luxembourg.[49]The only major setback during their rise in power came in 1288, whenHenry VIand his three brothers died at theBattle of Worringenwhile trying unsuccessfully to add theDuchy of Limburgto their realm. But despite the defeat, the Battle of Worringen helped the Counts of Luxembourg to achieve military glory, which they had previously lacked, as they had mostly enlarged their territory by means of inheritances, marriages and fiefdoms.[50]

The ascension of the Counts of Luxembourg culminated whenHenry VIIbecameKing of the Romans,King of Italyand finally, in 1312,Holy Roman Emperor.[51]

Golden Age: The House of Luxembourg contending for supremacy in Central Europe (1312–1443)[edit]

With the ascension of Henry VII as Emperor, the dynasty of theHouse of Luxembourgnot only began to rule theHoly Roman Empire,but rapidly began to exercise growing influence over other parts of Central Europe as well.

Henry's son,John the Blind,in addition to being Count of Luxembourg, also becameKing of Bohemia.He remains a major figure in Luxembourgish history andfolkloreand is considered by many historians the epitome ofchivalryin medieval times. He is also known for having founded theSchueberfouerin 1340 and for his heroic death at theBattle of Crécyin 1346.[52][53]John the Blind is considered anational heroin Luxembourg.[54]

In the 14th and early 15th centuries, three more members of the House of Luxembourg reigned as Holy Roman Emperors and Bohemian Kings: John's descendantsCharles IV,Sigismund(who also wasKing of Hungary and Croatia), andWenceslaus IV.Charles IV created the long-lastingGolden Bull of 1356,a decree which fixed important aspects of the constitutional structure of the Empire. Luxembourg remained an independent fief (county) of the Holy Roman Empire, and in 1354, Charles IV elevated it to the status of aduchywith his half-brotherWenceslaus Ibecoming the firstDuke of Luxembourg.While his kin were occupied ruling and expanding their power within the Holy Roman Empire and elsewhere, Wenceslaus, annexed theCounty of Chinyin 1364, and with it, the territories of the newDuchy of Luxembourgreached its greatest extent.[55]

During these 130 years, the House of Luxembourg was contending with theHouse of Habsburgfor supremacy within the Holy Roman Empire and Central Europe. It all came to end in 1443, when the House of Luxembourg suffered a succession crisis, precipitated by the lack of a male heir to assume the throne. Since Sigismund andElizabeth of Görlitzwere both heirless, all possessions of the Luxembourg Dynasty were redistributed among the European aristocracy.[56]The Duchy of Luxembourg become a possession ofPhilip the Good,Duke of Burgundy.[57]

As the House of Luxembourg had become extinct and Luxembourg now became part of theBurgundian Netherlands,this would mark the start of nearly 400 years of foreign rule over Luxembourg.

Luxembourg under Habsburg rule and repeated French invasions (1444–1794)[edit]

In 1482,Philip the Handsomeinherited all of what became then known as theHabsburg Netherlands,and with it the Duchy of Luxembourg. For nearly 320 years Luxembourg would remain a possession of the mighty House of Habsburg, at first under Austrian rule (1506–1556), then underSpanish rule (1556–1714),before going back again toAustrian rule (1714–1794).

With having become a Habsburg possession, the Duchy of Luxembourg became, like many countries in Europe at the time, heavily involved in the many conflicts for dominance of Europe between the Habsburg-held countries and theKingdom of France.

In 1542, theKing of France,François I,invaded Luxembourg twice, but the Habsburgs underCharles Vmanaged to reconquer the Duchy each time.[58]

Luxembourg became part of theSpanish Netherlandsin 1556, and when France and Spainwent to war in 1635it resulted in theTreaty of the Pyrenees,in whichthe first partition of Luxembourgwas decided. Under the Treaty, Spain ceded the Luxembourgish fortresses ofStenay,Thionville, andMontmédy,and the surrounding territory to France, effectively reducing the size of Luxembourg for the first time in centuries.[59]

In context of theNine Years' Warin 1684,France invaded Luxembourg again,conquering and occupying the Duchy until 1697 when it was returned to the Spanish in order to garner support for theBourboncause during the prelude to theWar of the Spanish Succession.When the war broke out in 1701 Luxembourg and the Spanish Netherlands were administered by the pro-French faction under the governorMaximilian II Emanuel, Elector of Bavariaand sided with the Bourbons. The duchy was subsequently occupied by the pro-Austrian allied forces during the conflict and was awarded to Austria at its conclusion in 1714.[60]

As the Duchy of Luxembourg repeatedly passed back and forth from Spanish and Austrian to French rule, each of the conquering nations contributed to strengthening and expanding theFortressthat the Castle of Luxembourg had become over the years. One example of this includes French military engineerMarquis de Vaubanwho advanced the fortifications around and on the heights of the city, fortification walls that are still visible today.[59]

Luxembourg under French rule (1794–1815)[edit]

During theWar of the First Coalition,Revolutionary Franceinvaded the Austrian Netherlands, and with it, Luxembourg, yet again. In the years 1793 and 1794 most of the Duchy was conquered relatively quickly and theFrench Revolutionary Armycommitted many atrocities and pillages against the Luxembourgish civilian population and abbeys, the most infamous being the massacres ofDifferdangeandDudelange,as well as the destruction of the abbeys ofClairefontaine,EchternachandOrval.[61][62]However the Fortress of Luxembourgresisted for nearly 7 monthsbefore the Austrian forces holding it surrendered. Luxembourg's long defense ledLazare Carnotto call Luxembourg "the best fortress in the world, except Gibraltar", giving rise to the city's nicknamethe Gibraltar of the North.[63]

Luxembourg was annexed by France, becoming thedépartement des forêts(department of forests), and the incorporation of the former Duchy as adépartementinto France was formalised at theTreaty of Campo Formioin 1797.[63] From the start of the occupation the new French officials in Luxembourg, who spoke only French, implemented many republican reforms, among them the principle oflaicism,which led to an outcry in strongly Catholic Luxembourg. Additionally French was implemented as the only official language and Luxembourgish people were barred access to all civil services.[64]When the French Army introduced military duty for the local population, riots broke out which culminated in 1798 when Luxembourgish peasants started a rebellion.[64]Even though the French managed to rapidly suppress this revolt calledKlëppelkrich,it had a profound effect on the historical memory of the country and its citizens.[65]

However, many republican ideas of this era continue to have a lasting effect on Luxembourg; one of the many examples features the implementation of the NapoleonicCode Civilwhich was introduced in 1804 and is still valid today.[66]

National awakening and independence (1815–1890)[edit]

After thedefeatofNapoleonin 1815, the Duchy of Luxembourg was restored. However, as the territory had been part of the Holy Roman Empire as well as the Habsburgian Netherlands in the past, both theKingdom of Prussiaand theUnited Kingdom of the Netherlandsnow claimed possession of the territory. At theCongress of Viennathe great powers decided that Luxembourg would become a member state of the newly formedGerman Confederation,but at the same timeWilliam I of the Netherlands,theKing of the Netherlands,would become, inpersonal union,the head of state. To satisfy Prussia, it was decided that not only theFortress of Luxembourgbe manned by Prussian troops, but also that large parts of Luxembourgish territory (mainly the areas around Bitburg and St. Vith) become Prussian possessions.[67]This marked the second time that the Duchy of Luxembourg was reduced in size, and is generally known as theSecond Partition of Luxembourg.To compensate the Duchy for this loss, it was decided to elevate the Duchy to aGrand-Duchy,thus giving the Dutch monarchs the additional title ofGrand-Duke of Luxembourg.

AfterBelgiumbecame an independent country following the victoriousBelgian Revolution of 1830–1831,it claimed the entire Grand-Duchy of Luxembourg as being part of Belgium, however, the Dutch King who was also Grand Duke of Luxembourg, as well as Prussia, did not want to lose their grip on the mighty fortress of Luxembourg and did not agree with the Belgian claims.[68]The dispute would be solved at the1839 Treaty of Londonwhere the decision of theThird Partition of Luxembourgwas taken. This time the territory was reduced by more than half, as the predominantlyfrancophonewestern part of the country(but also the then Luxembourgish-speaking part ofArelerland) was transferred to the new state of Belgium, thereby giving Luxembourg its modern-day borders. The treaty of 1839 also established full independence of the remaining Germanic-speaking Grand-Duchy of Luxembourg.[69][70][71][72]

In 1842 Luxembourg joined the German Customs Union (Zollverein).[73][74]This resulted in the opening of the German market, the development ofLuxembourg's steel industry,and expansion ofLuxembourg's railway networkfrom 1855 to 1875.

After theLuxembourg Crisisof 1866 nearly led to war between Prussia and France, as both were unwilling to see the other taking influence over Luxembourg and its mighty fortress, the Grand Duchy's independence and neutrality were reaffirmed by theSecond Treaty of Londonand Prussia was finally willing to withdraw its troops from the Fortress of Luxembourg under the condition that the fortifications would be dismantled. That happened the same year.[75]At the time of theFranco-Prussian warin 1870, Luxembourg's neutrality was respected, and neither France nor Germany invaded the country.[76]

As a result of the recurring disputes between the major European powers, the people of Luxembourg gradually developed a consciousness of independence and a national awakening took place in the 19th century.[77]The people of Luxembourg began referring to themselves asLuxembourgers,rather than being part of one of the larger surrounding nations. This consciousness ofMir wëlle bleiwe wat mir sinn( "We want to remain what we are ")culminated in 1890, when the last step towards full independence was finally taken: due to a succession crisis theDutch monarchyceased to hold the title Grand-Duke of Luxembourg. Beginning withAdolph of Nassau-Weilburg,the Grand-Duchy would havetheir own monarchy,thus reaffirming its full independence.[78]

Two German occupations and interwar political crisis (1890–1945)[edit]

In August 1914, duringWorld War I,Imperial Germanyviolated Luxembourg'sneutralityby invading it in order to defeat France.[79]Nevertheless, despite theGerman occupation,Luxembourg was allowed to maintain much of its independence and political mechanisms.[80]Unaware of the fact that Germany secretly planned to annex the Grand-Duchy in case of a German victory (theSeptemberprogramm), the Luxembourgish government continued to pursue a policy of strict neutrality. However, the Luxembourgish population did not believe Germany had good intentions, fearing that it would annex Luxembourg. Around 1,000 Luxembourgers served in the French army.[81]Their sacrifices have been commemorated at theGëlle Fra.[82]

After the war, Grand-DuchessMarie-Adélaïdewas seen by many people (including the French and Belgian governments) as having collaborated with the Germans and calls for her abdication and the establishment of aRepublicbecame louder.[83][84]After the retreat of theGerman army,communists in Luxembourg City andEsch-sur-Alzettetried to establish asoviet worker's republicsimilar to theones emerging in Germany,but these attempts lasted only 2 days.[84][83] In November 1918, a motion in theChamber of Deputiesdemanding theabolition of the monarchywas defeated narrowly by 21 votes to 19 (with 3 abstentions).[85]

France questioned the Luxembourgish government's, and especially Marie-Adélaïde's, neutrality during the war, and calls for an annexation of Luxembourg to either France or Belgium grew louder in both countries.[86]In January 1919, a company of theLuxembourgish Armyrebelled, declaring itself to be the army of the new republic, but French troops intervened and put an end to the rebellion.[86]Nonetheless, the disloyalty shown by her own armed forces was too much for Marie-Adélaïde, who abdicated in favor of her sisterCharlotte5 days later.[87]The same year, in apopular referendum,77.8% of the Luxembourgish population declared in favor of maintaining monarchy and rejected the establishment of a republic. During this time, Belgium pushed for an annexation of Luxembourg. However, all such claims were ultimately dismissed at theParis Peace Conference,thus securing Luxembourg's independence.[88]

In 1940, after the outbreak ofWorld War II,Luxembourg's neutrality was violated again whenNazi Germany'sWehrmachtentered the country,"entirely without justification".[89]In contrast to the First World War, under theGerman occupation of Luxembourg during World War II,the country was treated as German territory and informally annexed to the adjacent province ofNazi Germany,Gau Moselland.This time, Luxembourg did not remain neutral as Luxembourg'sgovernment in exilebased in London supported theAllies,sending a small group of volunteers who participated in theNormandy invasion,and multipleresistance groupsformed inside the occupied country.[90][91]

With 2.45% of its prewar population killed, and a third of all buildings in Luxembourg being destroyed or heavily damaged (mainly due to theBattle of the Bulge), Luxembourg suffered the highest such loss in Western Europe, but its commitment to the Allied war effort was never questioned.[92]Around 1,000–2,500 of Luxembourg's Jews were murdered inthe Holocaust.

Integration into NATO and European Union (1945–)[edit]

The Grand Duchy became a founding member of theUnited Nationsin 1945. Luxembourg's neutral status under theconstitutionformally ended in 1948, and in April 1949 it also became a founding member ofNATO.[93]During theCold War,Luxembourg continued its involvements on the side of theWestern Bloc.In the early fifties a small contingent of troops fought in theKorean War.[94] Luxembourg troops have also deployed to Afghanistan, to supportISAF.[95]

In the 1950s, Luxembourg became one of the six founding countries of theEuropean Communities,following the 1952 establishment of theEuropean Coal and Steel Community,and subsequent 1958 creations of theEuropean Economic CommunityandEuropean Atomic Energy Community.In 1993, the former two of these were incorporated into theEuropean Union.WithRobert Schuman(one of the founding fathers of the EU),Pierre Werner(considered the father of theEuro),Gaston Thorn,Jacques SanterandJean-Claude Juncker(all former Presidents of theEuropean Commission), Luxembourgish politicians contributed substantially to the EU's formation and establishment. In 1999, Luxembourg joined theeurozone.Thereafter, the country was elected non-permanent member of theUnited Nations Security Council(2013–14).

Thesteel industryexploiting theRed Lands' rich iron-ore grounds in the beginning of the 20th century drove Luxembourg's industrialization.[96]After the decline of the steel industry in the 1970s, the country focused on establishing itself asa global financial centerand developed into the banking hub it is reputed to be. Since the beginning of the 21st century, its governments have focused on developing the country into aknowledge economy,with the founding of theUniversity of Luxembourgand anational space program.

Government and politics[edit]

Luxembourg is described as a "full democracy",[97]with aparliamentary democracyheaded by aconstitutional monarch.Executive power is exercised by thegrand dukeand the cabinet, which consists of several members with the titles of minister, minister delegate or secretary of state, who are headed by a Prime Minister.[98]The currentConstitution of Luxembourg,the supreme law of Luxembourg, was originally adopted on 17 October 1868.[99]The Constitution was last updated on 1 July 2023.[100]

The grand duke has the power to dissolve thelegislature,in which case new elections must be held within three months. But since 1919, sovereignty has resided with the nation, exercised by the grand duke in accordance with the Constitution and the law.[101]

Legislative power is vested in theChamber of Deputies,aunicamerallegislature of sixty members, who are directly elected to five-year terms from fourconstituencies.A second body, theCouncil of State(Conseil d'État), composed of 21 ordinary citizens appointed by the grand duke, advises the Chamber of Deputies in the drafting of legislation.[102]

Luxembourg has three lower tribunals (justices de paix;inEsch-sur-Alzette,the city ofLuxembourg,andDiekirch), two district tribunals (Luxembourg and Diekirch), and aSuperior Court of Justice(Luxembourg), which includes the Court of Appeal and the Court of Cassation. There is also an Administrative Tribunal and an Administrative Court, as well as a Constitutional Court, all of which are located in the capital.

Administrative divisions[edit]

Luxembourg is divided into 12cantons,which are further divided into 100communes.[103]Twelve of the communes havecity status;the city ofLuxembourgis the largest.[104]

Capellen(1) -Clervaux(2) -Diekirch(3) -Echternach(4) -Esch-sur-Alzette(5) -Grevenmacher(6) -Luxembourg(7) -Mersch(8) -Redange(9) -Remich(10) -Vianden(11) -Wiltz(12)

Foreign relations[edit]

Luxembourg has long been a prominent supporter of European political andeconomic integration.In 1921, Luxembourg and Belgium formed theBelgium–Luxembourg Economic Union(BLEU) to create a regime of inter-exchangeable currency and a commoncustoms.[74]Luxembourg is a member of theBenelux Economic Unionand was one of the founding members of the European Economic Community (now the European Union). It also participates in theSchengen Group(named afterthe Luxembourg village of Schengenwhere the agreements were signed).[24]At the same time, the majority of Luxembourgers have consistently believed that European unity makes sense only in the context of a dynamic transatlantic relationship, and thus have traditionally pursued a pro-NATO,pro-US foreign policy.[105]

Luxembourg is considered a European capital, and is the site of theCourt of Justice of the European Union,theEuropean Court of Auditors,theEuropean Investment Bank,the Statistical Office of the European Union (Eurostat) and other vital EU organs. TheSecretariat of the European Parliamentis located in Luxembourg, but the Parliament usually meets inBrusselsand sometimes inStrasbourg.[106]Luxembourg is also site of theEFTA Court,which is responsible for the threeEFTAmembers who are part of the European Single Market through theEEA Agreement.[107]

Military[edit]

The Luxembourgish army is mostly based in its casern, theCentre militaire Caserne Grand-Duc Jeanon theHärebiergin Diekirch. The general staff is based in the capital, theÉtat-Major.[108]The army is undercivilian control,with the grand duke asCommander-in-Chief.TheMinister for Defense,Yuriko Backes,oversees army operations. The professional head of the army is theChief of Defense,who answers to the minister and holds the rank of general.

Being landlocked, Luxembourg has no navy. Seventeen NATOAWACSairplanes are registered as aircraft of Luxembourg.[109]In accordance with a joint agreement with Belgium, both countries have put forth funding for oneA400Mmilitary cargo plane.[citation needed]

Luxembourg has participated in theEurocorps,has contributed troops to theUNPROFORandIFORmissions in formerYugoslavia,and has participated with a small contingent in theNATOSFORmission inBosnia and Herzegovina.Luxembourg troops have also deployed toAfghanistan,to supportISAF.The army has also participated in humanitarian relief missions such as setting up refugee camps forKurdsand providing emergency supplies to Albania.[110]

Geography[edit]

Luxembourg is one of Europe's smallest countries, ranking168thin size of the194 independent countries of the world;it is about 2,586 square kilometers (998 sq mi) in size, measuring 82 km (51 mi) long and 57 km (35 mi) wide. It lies between latitudes49°and51° N,and longitudes5°and7° E.[111]

To the east, Luxembourg borders the GermanBundesländerofRhineland-PalatinateandSaarland,and to the south, it borders the FrenchrégionofGrand Est(Lorraine). The Grand Duchy borders Belgium'sWallonia,in particular the BelgianprovincesofLuxembourgandLiège,part of which comprises theGerman-speaking Community of Belgium,to the west and to the north, respectively.

The northern third of the country is known as theÉislekorOesling,and forms part of theArdennes.It is dominated by hills and low mountains, including theKneiffnearWilwerdange,[112]which is the highest point, at 560 meters (1,840 ft). Other mountains are theBuurgplaatzat 559 meters (1,834 ft) nearHuldangeand theNapoléonsgaardat 554 meters (1,818 ft) nearRambrouch.The region is sparsely populated, with only one town (Wiltz) with a population of more than five thousand people.

The southern two-thirds of the country is called theGuttland,and is more densely populated than the Éislek. It is also more diverse and can be divided into five geographic sub-regions. TheLuxembourg plateau,in south-central Luxembourg, is a large, flat,sandstoneformation, and the site of the city of Luxembourg.Little Switzerland,in the east of Luxembourg, has craggy terrain and thick forests. TheMosellevalley is the lowest-lying region, running along the southeastern border. TheRed Lands,in the far south and southwest, are Luxembourg's industrial heartland and home to many of Luxembourg's largest towns.

The border between Luxembourg and Germany is formed by three rivers: theMoselle,theSauer,and theOur.Other major rivers are theAlzette,theAttert,theClerve,and theWiltz.Thevalleysof the mid-Sauer and Attert form the border between the Gutland and the Éislek.

Environment[edit]

According to the 2012Environmental Performance Index,Luxembourg is one of the world's best performers in environmental protection, ranking 4th out of 132 assessed countries.[113]In 2020, it ranked second out of 180 countries.[114]Luxembourg also ranks 6th among the top ten most livable cities in the world by Mercer's.[115]The country wants to cutGHG emissionsby 55% in 10 years and reach zero emissions by 2050. Luxembourg wants to increase its organic farming fivefold.[116]It had a 2019Forest Landscape Integrity Indexmean score of 1.12/10, ranking it 164th globally out of 172 countries.[117]

Climate[edit]

Luxembourg has anoceanic climate(Köppen:Cfb), marked by high levels of precipitation, particularly in late summer. The summers are warm and winters cool.[118]

Economy[edit]

Luxembourg's stable and high-incomemarket economyfeatures moderate growth, low inflation, and a high level of innovation.[119]Unemployment is traditionally low, though it reached 6.1% by May 2012, due largely to the2008 global financial crisis.[120]In 2011, according to theIMF,Luxembourg was the world's second-richest country, with a per capita GDP on a purchasing-power parity (PPP) basis of $80,119.[121]Its GDP per capita in purchasing power standards was 261% of the EU average (100%) in 2019.[122]Luxembourg ranks 13th inThe Heritage Foundation'sIndex of Economic Freedom,[123]26th in the United NationsHuman Development Index,and 4th in the Economist Intelligence Unit'squality of life index.[124]It ranked 21st in theGlobal Innovation Indexin 2023, down from 18th in 2020.[125]

The industrial sector, dominated by steel until the 1960s, has since diversified to include chemicals, rubber, and other products. During recent decades, growth in the financial sector has more than compensated for the decline insteel production.Services, especially banking andfinance,account for the majority of the economic output. Luxembourg is the world's second-largest investment fund center (after the United States), the most important private banking center in theeurozoneand Europe's leading center for reinsurance companies. Moreover, Luxembourg's government has aimed to attract Internet startups, withSkypeandAmazonbeing two of the many Internet companies that have shifted their regional headquarters to Luxembourg. Other high-tech companies have established themselves in Luxembourg, including3D scannerdeveloper/manufacturerArtec 3D.[citation needed]

In April 2009, concern about Luxembourg's banking secrecy laws, as well as its reputation as atax haven,led to its being added to a "gray list" of nations with questionable banking arrangements by theG20.In response, the country soon adopted OECD standards on exchange of information and was subsequently added into the category of "jurisdictions that have substantially implemented the internationally agreed tax standard".[126][127]In March 2010, theSunday Telegraphreported that most ofKim Jong Il's $4 billion in secret accounts was in Luxembourg banks.[128]Amazon.co.uk also benefits from Luxembourg tax loopholes by channeling substantial U.K. revenues, as reported byThe Guardianin April 2012.[129]Luxembourg ranked third on theTax Justice Network's 2011Financial Secrecy Indexof the world's major tax havens, scoring only slightly behind theCayman Islands.[130]In 2013, Luxembourg was ranked the 2nd safest tax haven in the world, behindSwitzerland.

In early November 2014, just days after becoming head of theEuropean Commission,Luxembourg's former Prime MinisterJean-Claude Junckerwas hit by media disclosures—derived from a document leak known asLuxembourg Leaks—that Luxembourg had turned into a major European center of corporatetax avoidanceunder his premiership.[131]

Agriculture employed about 2.1% of Luxembourg's active population in 2010, when there were 2200 agricultural holdings with an average area per holding of 60 hectares.[132]

Luxembourg has especially close trade and financial ties to Belgium and the Netherlands (seeBenelux), and as a member of the EU it enjoys the advantages of the open Europeanmarket.[133]

With $171 billion in May 2015, the country ranked 11th in the world in holdings ofU.S. Treasury securities.[134]However, securities owned by non-Luxembourg residents, but held in custodial accounts in Luxembourg, are included in this figure.[135]

As of 2019[update],Luxembourg's public debt totaled $15,687,000,000, or $25,554 per capita. The debt to GDP was 22.10%.[136]

The Luxembourg labor market represents 445,000 jobs occupied by 120,000 Luxembourgers, 120,000 foreign residents and 205,000 cross-border commuters. The latter pay their taxes in Luxembourg, but their education and social rights are the responsibility of their country of residence. The same applies to pensioners. Luxembourg's government has never shared its tax revenues with the local authorities on theFrench border.This system is seen as one of the keys to Luxembourg's economic growth, but at the expense of the border countries.[137]

Transport[edit]

Luxembourg has road, rail and air transport facilities and services. The road network has been significantly modernized in recent years with 165 km (103 mi)[138]of motorways connecting the capital to adjacent countries. The advent of the high-speedTGVlink to Paris has led to renovation of the city'srailway stationand a new passenger terminal atLuxembourg Airportwas opened in 2008.[139]Luxembourg City reintroducedtramsin December 2017 and there are plans to openlight-raillines in adjacent areas within the next few years.[140]

There are 681 cars per 1000 persons in Luxembourg—higher than most of otherstates,and surpassed by theUnited States,Canada,Australia,New Zealand,Iceland,and other small states likePrincipality of Monaco,San Marino,Liechtenstein,theBritish overseas territory of Gibraltar,andBrunei.[141]

On 29 February 2020, Luxembourg became the first country to introduceno-charge public transportation,which will be almost completely funded by public expenditure.[142]

Communications[edit]

Thetelecommunications industryin Luxembourg is liberalized and the electronic communications networks are significantly developed. Competition between the different operators is guaranteed by the legislative framework Paquet Telecom[143]of the Government of 2011 which transposes the European Telecom Directives into Luxembourgish law. This encourages the investment in networks and services. The regulator ILR – Institut Luxembourgeois de Régulation[144]ensures the compliance to these legal rules.[citation needed]

Luxembourg has modern and widely deployed optical fiber and cable networks throughout the country. In 2010, the Luxembourg Government launched its National strategy for very high-speed networks with the aim to become a global leader in terms of very high-speed broadband by achieving full 1 Gbit/s coverage of the country by 2020.[145]In 2011, Luxembourg had anNGAcoverage of 75%.[146]In April 2013 Luxembourg featured the 6th highest download speed worldwide and the 2nd highest in Europe: 32,46 Mbit/s.[147]The country's location in Central Europe, stable economy and low taxes favour the telecommunication industry.[148][149][150]

It ranks 2nd in the world in the development of the Information and Communication Technologies in the ITU ICT Development Index and 8th in the Global Broadband Quality Study 2009 by theUniversity of Oxfordand theUniversity of Oviedo.[151][152][153][154]

Luxembourg is connected to all major European Internet Exchanges (AMS-IX Amsterdam,[155]DE-CIX Frankfurt,[156]LINX London),[157]datacenters and POPs through redundant optical networks.[158][159][160][161][162]In addition, the country is connected to the virtual meetme room services (vmmr)[163]of the international data hub operator Ancotel.[164]This enables Luxembourg to interconnect with all major telecommunication operators[165]and data carriers worldwide. The interconnection points are in Frankfurt, London, New York and Hong Kong.[166]Luxembourg has established itself as one of the leadingfinancial technology(FinTech) hubs in Europe, with the Luxembourg government supporting initiatives like the Luxembourg House of Financial Technology.[167]

Some 20 data centers[168][169][170]are operating in Luxembourg. Six data centers are Tier IV Design certified: three of ebrc,[171]two of LuxConnect[172][173]and one of European Data Hub.[174]In a survey on nine international data centers carried out in December 2012 and January 2013 and measuring availability (up-time) and performance (delay by which the data from the requested website was received), the top three positions were held by Luxembourg data centers.[175][176]

Demographics[edit]

Largest towns[edit]

Largest cities or towns in Luxembourg

2023 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Name | Canton | Pop. | ||||||

Luxembourg  Esch-sur-Alzette |

1 | Luxembourg | Luxembourg Canton | 132,780 |  Differdange  Dudelange | ||||

| 2 | Esch-sur-Alzette | Esch-sur-Alzette Canton | 36,625 | ||||||

| 3 | Differdange | Esch-sur-Alzette Canton | 29,536 | ||||||

| 4 | Dudelange | Esch-sur-Alzette Canton | 21,952 | ||||||

| 5 | Pétange | Esch-sur-Alzette Canton | 20,563 | ||||||

| 6 | Sanem | Esch-sur-Alzette Canton | 18,333 | ||||||

| 7 | Hesperange | Luxembourg Canton | 16,433 | ||||||

| 8 | Bettembourg | Esch-sur-Alzette Canton | 11,422 | ||||||

| 9 | Schifflange | Esch-sur-Alzette Canton | 11,363 | ||||||

| 10 | Käerjeng | Capellen Canton | 11,015 | ||||||

Ethnicity[edit]

The people of Luxembourg are calledLuxembourgers.[178]The immigrant population increased in the 20th century due to the arrival of immigrants fromBelgium,France, Italy, Germany, andPortugal;the latter comprised the largest group. In 2013 about 88,000 Luxembourg inhabitants possessedPortuguesenationality.[179]In 2013, there were 537,039 permanent residents, 44.5% of which were of foreign background or foreign nationals; the largest foreign ethnic groups were the Portuguese, comprising 16.4% of the total population, followed by the French (6.6%), Italians (3.4%), Belgians (3.3%) and Germans (2.3%). Another 6.4% were of other EU background, while the remaining 6.1% were of other non-EU, but largely other European, background.[180]

Since the beginning of theYugoslav wars,Luxembourg has seen many immigrants fromBosnia and Herzegovina,Montenegro,andSerbia.Annually, over 10,000 new immigrants arrive in Luxembourg, mostly from the EU states, as well as Eastern Europe. In 2000 there were 162,000 immigrants in Luxembourg, accounting for 37% of the total population. There were an estimated 5,000 illegal immigrants in Luxembourg in 1999.[181]

Language[edit]

Luxembourg does not have any "official" languages per se. As determined by the 1984 Language Regimen Act (French:Loi sur le régime des langues),Luxembourgishis the solenational languageof the Luxembourgish people.[13]It is considered the mother tongue or "language of the heart" for Luxembourgers and the language they generally use to speak or write to each other. Luxembourgish as well as the dialects in adjacent Germany belong to theMoselle Franconiansubgroup of the mainWest Central Germandialect group, which are largely mutually intelligible across the border, but Luxembourgish also has more than 5,000 words of French origin.[182][183]Knowledge of Luxembourgish is a criterion fornaturalisation.[184]

In addition to Luxembourgish,FrenchandGermanare used in administrative and judicial matters, making all threeadministrative languagesof Luxembourg.[13]Per article 4 of the law promulgated in 1984, if a citizen asks a question in Luxembourgish, German or French, the administration must reply, as far as possible, in the language in which the question was asked.[13]

Luxembourg is largely multilingual: in 2012, 52% of citizens claimed Luxembourgish as their native language, 16.4%Portuguese,16% French, 2% German and 13.6% different languages (mostlyEnglish,ItalianorSpanish).[185][186]Though not the most common mother tongue in Luxembourg, French is the most widely-known language in the country: in 2021, 98% of citizens were able to speak it to a high level.[187]The vast majority of Luxembourg residents are able to speak it as a second or third language.[188]As of 2018[update],much of the population was able to speak multiple other languages: 80% of citizens reported being able to hold a conversation in English, 78% in German and 77% in Luxembourgish, claiming these languages as their respective second, third or fourth language.[187]

Each of the three official languages is used as a primary language in certain spheres of everyday life, without being exclusive. Luxembourgish is the language that Luxembourgers generally use to speak and write to each other, and there has been a recent[when?]increase in the production of novels and movies in the language.[citation needed]At the same time, the numerous expatriate workers (approximately 44% of the population) generally do not use it to speak to each other.[189]

Most official business and written communication is carried out in French, which is also the language mostly used for public communication, with written official statements, advertising displays and road signs generally in French. Due to the historical influence of the Napoleonic Code on the legal system of the Grand Duchy, French is also the sole language of the legislation and generally the preferred language of the government, administration and justice. Parliamentary debates are mostly conducted in Luxembourgish, whereas written government communications and official documents (e.g. administrative or judicial decisions, passports, etc.) are drafted mostly in French and sometimes additionally in German.[citation needed]

Although professional life is largely multilingual, French is described by private sector business leaders as the main working language of their companies (56%), followed by Luxembourgish (20%), English (18%), and German (6%).[190]

German is very often used in much of the media along with French and is considered by most Luxembourgers their second language. This is mostly due to the high similarity of German to Luxembourgish but also because it is the first language taught to children in primary school (language of literacy acquisition).[191]

Due to the largecommunity of Portuguese origin,the Portuguese language is fairly prevalent in Luxembourg, though it remains limited to the relationships inside this community. Portuguese has no official status, but the administration sometimes makes certain informative documents available in Portuguese.[citation needed]

Even though Luxembourg is largely multilingual today, some people claim that Luxembourg is subject of intensefrancizationand that Luxembourgish and German are in danger of disappearing in the country, making Luxembourg either a unilingual Francophone country, or at best a bilingual French- and English-speaking country sometime in the far future.[192][193][188]

Religion[edit]

Luxembourg is asecular state,but the state recognizes certain religions as officially mandated religions. This gives the state a hand in religious administration and appointment of clergy, in exchange for which the state pays certain running costs and wages. Religions covered by such arrangements areCatholicism,Judaism,Greek Orthodoxy,Anglicanism,Russian Orthodoxy,Lutheranism,Calvinism,Mennonitism,andIslam.[194]

Since 1980, it has been illegal for the government to collect statistics on religious beliefs or practices.[195]A 2000 estimate by theCIA Factbookis that 87% of Luxembourgers are Catholic, including the grand ducal family, with the remaining 13% being Protestants, Orthodox Christians, Jews, Muslims, and those of other or no religion.[196]According to a 2010Pew Research Centerstudy, 70.4% are Christian, 2.3% Muslim, 26.8% unaffiliated, and 0.5% other religions.[197]

According to a 2005Eurobarometerpoll,[198]44% of Luxembourg citizens responded that "they believe there is a God", whereas 28% answered that "they believe there is some sort of spirit or life force", and 22% that "they do not believe there is any sort of spirit, god, or life force".

Education[edit]

Luxembourg's education systemis trilingual: the first years of primary school are in Luxembourgish, before changing to German; while in secondary school, the language of instruction changes to French.[199]Proficiency in all three languages is required for graduation from secondary school. In addition to the three national languages, English is taught in compulsory schooling and much of the population of Luxembourg can speak English. The past two decades have highlighted the growing importance of English in several sectors, in particular the financial sector. Portuguese, the language of the largest immigrant community, is also spoken by large segments of the population, but by relatively few from outside the Portuguese-speaking community.[200]

TheUniversity of Luxembourgis the only university based in Luxembourg. In 2014,Luxembourg School of Business,a graduate business school, was created through private initiative and received the accreditation from the Ministry of Higher Education and Research of Luxembourg in 2017.[201][202]Two American universities maintain satellite campuses in the country:Miami University(Dolibois European Center) andSacred Heart University(Luxembourg Campus).[203]

Health[edit]

According to data from theWorld Health Organization,healthcare spending on behalf of the government of Luxembourg topped $4.1 Billion, amounting to about $8,182 for each citizen in the nation.[204][205]The nation of Luxembourg collectively spent nearly 7% of itsGross Domestic Producton health, placing it among the highest spending countries on health services and related programs in 2010 among other well-off nations in Europe with high average income among its population.[206]

Culture[edit]

Luxembourg has been heavily influenced by the culture of its neighbors. It retains a number of folk traditions, having been for much of its history a profoundly rural country. There are several notable museums, located mostly in the capital. These include theNational Museum of History and Art(NMHA), theLuxembourg City History Museum,and the newGrand Duke Jean Museum of Modern Art(Mudam). TheNational Museum of Military History (MNHM)in Diekirch is especially known for its representations of theBattle of the Bulge.TheHistoric city of Luxembourg city including its fortificationis part of theUNESCOWorld Heritage List,on account of the historical importance of its fortifications.[207][unreliable source?]

The country has produced some internationally known artists, including the paintersThéo Kerg,Joseph KutterandMichel Majerus,and photographerEdward Steichen,whoseThe Family of Manexhibition has been placed on UNESCO'sMemory of the Worldregister, and is now permanently housed inClervaux.Editor and authorHugo Gernsback,whose publications crystallized the concept ofscience fiction,was born in Luxembourg City. Movie starLoretta Youngwas of Luxembourgish descent.[208]

Luxembourg was a founding participant of theEurovision Song Contest,and participated every year between1956and before it was relegated after the1993competition, with the exception of 1959. Although Luxembourg was free to participate again in1995,it chose not to return to the competition before2024.It has won the competition a total of five times,1961,1965,1972,1973and1983and hosted the contest in1962,1966,1973,and1984.Only nine of its 38 entries before 2024, and none of its five winning entries, were performed byLuxembourgishartists.[209]On its2024return, this was, however, with a particular emphasis on promoting music and artists from Luxembourg.[210]

Luxembourg was the first city to be namedEuropean Capital of Culturetwice. The first time was in 1995. In 2007, the European Capital of Culture was to be a cross-border area consisting of the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg, the Rheinland-Pfalz and Saarland in Germany, the Walloon Region and the German-speaking part of Belgium, and theLorrainearea in France.[211]The event was an attempt to promote mobility and the exchange of ideas, crossing borders physically, psychologically, artistically and emotionally.[citation needed]

Luxembourg was represented at the WorldExpo 2010in Shanghai, China, from 1 May to 31 October 2010 with its own pavilion.[212][213]The pavilion, designed as a forest and fortress, was based on the transliteration of the word Luxembourg into Chinese, "Lúsēnbǎo", which when directly translated, means "forest and fortress". It represented Luxembourg as the "Green Heart in Europe".[214]

Sports[edit]

Unlike most countries in Europe, sports in Luxembourg are not concentrated upon a particularnational sport,but instead encompass a number of sports, both team and individual. Despite the lack of a central sporting focus, over 100,000 people in Luxembourg, out of a total population of 660,000, are licensed members of one sports federation or another.[215]TheStade de Luxembourg,situated inGasperich,southernLuxembourg City,is the country'snational stadiumand largest sports venue in the country with a capacity of 9,386 for sporting events, including football and rugby union, and 15,000 for concerts.[216]The largestindoor venuein the country isd'Coque,Kirchberg,north-easternLuxembourg City,which has a capacity of 8,300. The arena is used forbasketball,handball,gymnastics,andvolleyball,including the final of the2007 Women's European Volleyball Championship.[217]Hess Cycling Teamis a Luxembourgish women's road cycling team.[218]

Cuisine[edit]

Luxembourg cuisine reflects its position on the border between the Latin and Germanic worlds, being heavily influenced by the cuisines of neighboring France and Germany. More recently,[when?]it has been enriched by its many Italian and Portuguese immigrants.[219]

Most native Luxembourg dishes, consumed as the traditional daily fare, share roots in the country's folk dishes, the same as in neighboringGermany.[220]

Luxembourg sells the most alcohol in Europe per capita.[221]However, the large proportion of alcohol purchased by customers from neighboring countries contributes to the statistically high level of alcohol sales per capita; this level of alcohol sales is thus not representative of the actual alcohol consumption of the Luxembourg population.[222]

Luxembourg has the second highest number ofMichelin-starredrestaurants per capita with Japan ranked at number one and Switzerland following Luxembourg at number three.[223]

Media[edit]

The main languages of media in Luxembourg are French and German. The newspaper with the largest circulation is the German-language dailyLuxemburger Wort.[224]Because of the strong multilingualism in Luxembourg, newspapers often alternate articles in French and articles in German, without translation. In addition, there are both English and Portuguese radio and national print publications, but accurate audience figures are difficult to gauge since the national media survey by ILRES is conducted in French.[225]

Luxembourg is known in Europe for its radio and television stations (Radio LuxembourgandRTL Group). It is also the uplink home ofSES,carrier of major European satellite services for Germany and Britain.[226]

Due to a 1988 law that established a special tax scheme for audiovisual investment, the film and co-production in Luxembourg has grown steadily.[227]There are some 30 registered production companies in Luxembourg.[228][229]

Luxembourg won anOscarin 2014 in theAnimated Short Filmscategory withMr Hublot.[230]

Notable Luxembourgers[edit]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

Informational notes[edit]

- ^European Unionsince 1993

- ^Luxembourgish:Groussherzogtum Lëtzebuerg[ˈɡʀəʊ̯sˌhɛχtsoːχtumˈlətsəbuəɕ];French:Grand-Duché de Luxembourg[ɡʁɑ̃dyʃedəlyksɑ̃buʁ];German:Großherzogtum Luxemburg[ˈɡʁoːsˌhɛʁtsoːktuːmˈlʊksm̩bʊʁk].

Citations[edit]

- ^"The World Factbook".Central Intelligence Agency.24 November 2020.Archivedfrom the original on 9 January 2021.Retrieved11 December2020.

- ^Eurobarometer 90.4: Attitudes of Europeans towards Biodiversity, Awareness and Perceptions of EU customs, and Perceptions of Antisemitism.European Commission. Archived fromthe originalon 13 March 2020.Retrieved15 July2019– viaGESIS.

- ^"Surface water and surface water change".Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development(OECD).Archivedfrom the original on 24 March 2021.Retrieved11 October2020.

- ^"Une croissance démographique réduite en 2023"(PDF).statistiques.public.lu(in French). 18 April 2024.Archived(PDF)from the original on 18 April 2024.Retrieved18 April2024.

- ^"Évolution de la population".Statistiques - Luxembourg(in French). 10 February 2023.Archivedfrom the original on 16 April 2023.Retrieved18 April2023.

- ^abcd"World Economic Outlook Database, April 2024 Edition".IMF.org.International Monetary Fund.Archivedfrom the original on 18 April 2024.Retrieved18 April2024.

- ^"Gini coefficient of equivalised disposable income – EU-SILC survey".ec.europa.eu.Eurostat.Archivedfrom the original on 9 October 2020.Retrieved9 August2021.

- ^"Human Development Report 2023/2024"(PDF).United Nations Development Programme.13 March 2024.Archived(PDF)from the original on 13 March 2024.Retrieved13 March2024.

- ^"Luxembourg".The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language(5th ed.). HarperCollins.Retrieved1 October2019.

- ^"Europe:: Luxembourg — The World Factbook - Central Intelligence Agency".www.cia.gov.Archivedfrom the original on 9 January 2021.Retrieved12 December2020.

- ^"Decision of the Representatives of the Governments of the Member States on the location of the seats of the institutions (12 December 1992)".Centre virtuel de la connaissance sur l'Europe.2014. Archived fromthe originalon 13 October 2019.Retrieved24 October2017.

- ^"Luxembourg | national capital, Luxembourg".Encyclopedia Britannica.Archivedfrom the original on 17 November 2020.Retrieved12 December2020.

- ^abcde"Loi du 24 février 1984 sur le régime des langues".legilux.public.lu.Archivedfrom the original on 18 September 2023.Retrieved13 September2021.

- ^Constitution du Grand Duché de Luxembourg(in French, Luxembourgish, and German). Brochure distribuée par la chambre des députés (48 pages). 2023. p. 4: Chapter I, Section 1, article 4. "La langue du Grand-Duché de Luxembourg est le luxembourgeois. La loi règle l'emploi des langues luxembourgeoise, francaise et allemande.".

- ^"Eurostat – Tables, Graphs and Maps Interface (TGM) table".Epp.eurostat.ec.europa.eu.Archivedfrom the original on 18 April 2009.Retrieved21 February2010.

- ^"La démographie luxembourgeoise en chiffres"(PDF).Le Portail des Statistiques(in French). Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 21 March 2022.Retrieved1 November2021.

- ^"Country comparison:: POPULATION growth rate".The World Factbook.Archived fromthe originalon 27 May 2016.Retrieved16 April2017.

- ^Krouse, Sarah (1 January 2018). "Piping Hot Gromperekichelcher, Only if You Pass the Sproochentest".The Wall Street Journal.p. 1.

- ^"Country Ranking - Rainbow Europe".rainbow-europe.org.Archivedfrom the original on 21 May 2019.Retrieved28 October2021.

- ^"Human Development Report 2021/2022"(PDF).United Nations Development Programme.8 September 2022.Archived(PDF)from the original on 8 September 2022.Retrieved8 September2022.

- ^ab"City of Luxembourg: its Old Quarters and Fortifications".World Heritage List.UNESCO, World Heritage Convention.Archivedfrom the original on 26 January 2020.Retrieved16 April2017.

- ^"European Union | Definition, Purpose, History, & Members".Encyclopedia Britannica.Archivedfrom the original on 9 October 2023.Retrieved12 December2020.

- ^Timeline: Luxembourg – A chronology of key eventsArchived13 May 2007 at theWayback MachineBBC News Online, 9 September 2006. Retrieved 8 October 2006.

- ^ab"Independent Luxembourg".Encyclopedia Britannica.Archivedfrom the original on 5 March 2021.Retrieved12 December2020.

- ^"Asselborn's final Security Council meeting".Luxemburger Wort.19 December 2014. Archived fromthe originalon 10 October 2017.Retrieved2 April2015.

- ^About... The History of Luxembourg.Information and Press Service of the Government. 2022. p. 4.ISBN978-2-87999-298-3.Archivedfrom the original on 24 January 2024.Retrieved24 January2024.

- ^Kreins, Jean-Marie (2010).Histoire du Luxembourg(5 ed.). Paris, France: Presses Universitaires de France.

- ^About... The History of Luxembourg.Information and Press Service of the Government. 2022. p. 5.ISBN978-2-87999-298-3.Archivedfrom the original on 24 January 2024.Retrieved24 January2024.

- ^"Henry VII, Holy Roman emperor".Encyclopedia Britannica.Archivedfrom the original on 31 March 2019.Retrieved12 December2020.

- ^ab"Luxembourg - History".Encyclopedia Britannica.Archivedfrom the original on 5 March 2021.Retrieved12 December2020.

- ^About... The History of Luxembourg.Information and Press Service of the Government. 2022. pp. 9–10.ISBN978-2-87999-298-3.Archivedfrom the original on 24 January 2024.Retrieved24 January2024.

- ^"City of Luxembourg: its Old Quarters and Fortifications".UNESCO World Heritage Centre.Archivedfrom the original on 5 October 2020.Retrieved12 August2021.

- ^About... The History of Luxembourg.Information and Press Service of the Government. 2022. pp. 12–14.ISBN978-2-87999-298-3.Archivedfrom the original on 24 January 2024.Retrieved24 January2024.

- ^abAbout... The History of Luxembourg.Information and Press Service of the Government. 2022. pp. 14–17.ISBN978-2-87999-298-3.Archivedfrom the original on 24 January 2024.Retrieved24 January2024.

- ^abBeckwith, John (1979).Early Christian and Byzantine art.Penguin Books. p. 122.ISBN0-14-056133-1.OCLC4774770.

- ^Michel Pauly, Geschichte Luxemburgs 2013 p. 9

- ^Michel Pauly, Geschichte Luxemburgs 1988 (2013)p. 16

- ^"Mosaïque de Vichten".-: Mosaïque de Vichten, -: - -.Archivedfrom the original on 21 April 2021.Retrieved21 April2021.

- ^abTrausch, Gilbert (2003).Histoire du Luxembourg: le destin européen d'un petit pays(in French). Toulouse: Privat.ISBN2-7089-4773-7.OCLC52386195.

- ^"Francique".www.axl.cefan.ulaval.ca.Archivedfrom the original on 26 January 2021.Retrieved21 April2021.

- ^Michel Pauly, Geschichte Luxemburgs 2013 p. 23

- ^The Emperor's Bible ". Uppsala University Library. Retrieved 17 October 2020

- ^Pauly, Michel (2011).Geschichte Luxemburgs(in German). München: Verlag C.H. Beck.ISBN978-3-406-62225-0.OCLC724990605.

- ^"Luxembourg's Origins".9 January 2024.Archivedfrom the original on 24 January 2024.Retrieved24 January2024.

- ^Michel Pauly, Geschichte Luxemburgs 2013 p. 26

- ^Kreins (2003), p. 20

- ^About... The History of Luxembourg.Information and Press Service of the Government. 2022.ISBN978-2-87999-298-3.Archivedfrom the original on 24 January 2024.Retrieved24 January2024.

- ^Michel Pauly, Geschichte Luxemburgs 2013 p. 28

- ^Michel Pauly, Geschichte Luxemburgs 2013 p.33-34

- ^Michel Pauly, Geschichte Luxemburgs 2013 p.35

- ^Michel Pauly, Geschichte Luxemburgs 2013 p.37

- ^Margue, Paul (1974).Luxemburg in Mittelalter und Neuzeit.Editions Bourg-Bourger.

- ^Gilbert Trausch, Le Luxembourg, émergence d'un état et d'une nation 2007 p. 93 Edition Schortgen

- ^"At the Helm of the Holy Roman Empire".Luxembourg.lu.9 January 2024.Archivedfrom the original on 24 January 2024.Retrieved24 January2024.

- ^Michel Pauly, Geschichte Luxemburgs 2013 p. 41

- ^Kreins (2003), p. 39

- ^Michel Pauly, Geschichte Luxemburgs 2013 p. 44

- ^Michel Pauly, Geschichte Luxemburgs 2013 p.53

- ^abMichel Pauly, Geschichte Luxemburgs 2013 p.57

- ^Michel Pauly, Geschichte Luxemburgs 2013 p.58

- ^"Dark Luxembourg: The French massacre of Differdange".Archivedfrom the original on 6 October 2021.Retrieved6 October2021.

- ^"LUXEMBOURG - 17 mai 1794 - MASSACRE DE DUDELANGE - l'HORRIBLE FIN DE PIERRE GAASCH, GARDE-FORESTIER... - la Maraîchine Normande".24 March 2016.Archivedfrom the original on 6 October 2021.Retrieved6 October2021.

- ^abKreins (2003), p.64

- ^abMichel Pauly, Geschichte Luxemburgs 2013 p.65

- ^Kreins (2003), p. 66

- ^Michel Pauly, Geschichte Luxemburgs 2013 p.67

- ^Johan Christiaan Boogman: Nederland en de Duitse Bond 1815–1851. Diss. Utrecht, J. B. Wolters, Groningen / Djakarta 1955, pp. 5–8.

- ^Michel Pauly Die Geschichte Luxemburgs 2013 p. 68

- ^Thewes, Guy (2006) (PDF). Les gouvernements du Grand-Duché de Luxembourg depuis 1848 (2006), p. 208

- ^"LUXEMBURG Geschiedenis".Landenweb.net.Archivedfrom the original on 10 May 2013.Retrieved1 February2013.

- ^"The World Factbook".Central Intelligence Agency. Archived fromthe originalon 27 February 2013.Retrieved1 February2013.

- ^Microsoft Encarta Encyclopedia 1997

- ^Kreins (2003), p. 76

- ^abHarmsen, Robert; Högenauer, Anna-Lena (28 February 2020), "Luxembourg and the European Union",Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Politics,Oxford University Press,doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780190228637.013.1041,ISBN978-0-19-022863-7

- ^Kreins (2003), pp. 80–81

- ^Maartje Abbenhuis,An Age of Neutrals: Great Power Politics, 1815–1914.Cambridge University Press (2014)ISBN978-1-107-03760-1

- ^Michel Pauly, Geschichte Luxemburgs 2013 p.75

- ^Kreins (2003), p. 84

- ^"The First World War: German Occupation and State Crisis".Luxembourg.lu.9 January 2024.Archivedfrom the original on 24 January 2024.Retrieved24 January2024.

- ^Michel Pauly, Geschichte Luxemburgs 2013 p.83

- ^About... The History of Luxembourg.Information and Press Service of the Government. 2022. p. 22.ISBN978-2-87999-298-3.Archivedfrom the original on 24 January 2024.Retrieved24 January2024.

- ^"Gëlle Fra – a Hallmark of Society and Luxembourgish History".Luxembourg.lu.26 June 2023.Archivedfrom the original on 24 January 2024.Retrieved24 January2024.

- ^abThewes (2003), p. 81

- ^abKreins (2003), p. 89.

- ^Michel Pauly, Geschichte Luxemburgs 2013 p.84

- ^abMichel Pauly, Geschichte Luxemburgs 2013 p.85

- ^Dostert et al. (2002), p. 21

- ^Brousse, Hendry."Le Luxembourg de la guerre à la paix (1918 – 1923): la France, actrice majeure de cette transition".hal.univ-lorraine.fr.Archivedfrom the original on 3 March 2021.Retrieved18 April2021.

- ^"The invasion of Belgium, The Netherlands and Luxembourg".Judgment of the International Military Tribunal For The Trial of German Major War Criminals.London: HM Stationery Office. 1951. Archived fromthe originalon 7 February 2019.Retrieved22 December2021– via The Nizkor Project.

- ^Dostert, Paul."Luxemburg unter deutscher Besatzung 1940-45: Die Bevölkerung eines kleinen Landes zwischen Kollaboration und Widerstand".Zug der Erinnerung(in German).Archivedfrom the original on 2 June 2019.Retrieved23 April2021.

- ^"The Second World War: the Toughest Ordeal".Luxembourg.lu.9 January 2024.Archivedfrom the original on 24 January 2024.Retrieved24 January2024.

- ^Michel Pauly, Geschichte Luxemburgs 2013 p.102

- ^"Luxembourg and NATO".NATO.Archivedfrom the original on 14 April 2021.Retrieved18 April2021.

- ^"D'Koreaner aus dem Lëtzebuerger Land (Koreans from Luxembourg)".Archivedfrom the original on 24 January 2024.Retrieved24 January2024.

- ^"ISAF (International Security and Assistance Force)".24 April 2023. Archived fromthe originalon 27 April 2021.Retrieved24 April2021.

- ^"The Steel Industry That Made Luxembourg's Fortune".Luxembourg.lu.9 January 2024.Archivedfrom the original on 24 January 2024.Retrieved24 January2024.

- ^solutions, EIU digital."Democracy Index 2016 - The Economist Intelligence Unit".www.eiu.com.Archivedfrom the original on 11 November 2019.Retrieved29 November2017.

- ^"Government Composition".Gouvernement.lu.28 May 2013.Archivedfrom the original on 19 December 2023.Retrieved24 January2024.

- ^"Mémorial A, 1868, No.25, Constitution du Grand-Duché de Luxembourg".Legilux.lu(in French).Archivedfrom the original on 27 November 2023.Retrieved24 January2024.

- ^"Constitution du Grand-Duché de Luxembourg".Legilux(in French).Retrieved24 January2024.

- ^"Constitution of Luxembourg"(PDF).Service central de législation. 2005. Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 16 February 2008.Retrieved23 July2006.

- ^"Structure of the Conseil d'Etat".Conseil d'Etat. Archived fromthe originalon 19 June 2006.Retrieved23 July2006.

- ^"Luxembourg's territory".Luxembourg.public.lu. 20 September 2020.Archivedfrom the original on 25 September 2023.Retrieved18 April2023.

- ^"Luxembourg - Communications".Encyclopedia Britannica.Archivedfrom the original on 5 March 2021.Retrieved12 December2020.

- ^"Interdependence, States and Community: Ethical Concerns and Foreign Policy in ASEAN",The Ethics of Foreign Policy,Routledge, 23 March 2016, pp. 151–164,doi:10.4324/9781315616179-19,ISBN978-1-315-61617-9[clarification needed]

- ^"The European institutions in Luxembourg".luxembourg.public.lu.Archivedfrom the original on 19 January 2021.Retrieved12 December2020.

- ^EFTA Court homepageArchived3 February 2023 at theWayback Machine,Retrieved 3 February 2023.

- ^SA, Interact."Accueil".www.armee.lu(in French).Archivedfrom the original on 10 March 2011.Retrieved13 September2017.

- ^"Luxembourg".Aeroflight.co.uk. 8 September 2005.Archivedfrom the original on 29 May 2015.Retrieved23 July2006.

- ^"Luxembourg Army History".2 July 2010. Archived fromthe originalon 2 July 2010.Retrieved19 December2019.

- ^"Where is Luxembourg?".WorldAtlas.Archivedfrom the original on 3 September 2018.Retrieved3 September2018.

- ^"Mountains in Luxembourg"(PDF).Archived from the original on 10 June 2007.Retrieved24 February2010.

{{cite web}}:CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link),recueil de statistiques par commune. statistiques.public.lu (2003) p. 20 - ^"2012 EPI:: Rankings – Environmental Performance Index".yale.edu.5 May 2012. Archived fromthe originalon 5 May 2012.

- ^"What is the greenest country in the world?".ATLAS & BOOTS.6 June 2020.Archivedfrom the original on 27 November 2020.Retrieved20 November2020.

- ^"MAE – Luxembourg City in the top 10 of the most" livable "cities / News / New York CG / Mini-Sites".Newyork-cg.mae.lu.Archived fromthe originalon 29 June 2017.Retrieved23 July2017.

- ^SCHNUER, CORDULA."LUX MUST" REDOUBLE ITS EFFORTS "TO MEET CLIMATE TARGETS: OECD".Delano.Archivedfrom the original on 19 November 2020.Retrieved20 November2020.

- ^Grantham, H. S.; et al. (2020)."Anthropogenic modification of forests means only 40% of remaining forests have high ecosystem integrity - Supplementary Material".Nature Communications.11(1): 5978.Bibcode:2020NatCo..11.5978G.doi:10.1038/s41467-020-19493-3.ISSN2041-1723.PMC7723057.PMID33293507.S2CID228082162.

- ^"Luxembourg".Stadtklima (Urban Climate). Archived fromthe originalon 28 September 2007.Retrieved19 April2007.

- ^"The Global Innovation Index 2012"(PDF).INSEAD.Archived(PDF)from the original on 30 August 2012.Retrieved22 July2012.

- ^"Statistics Portal // Luxembourg – Home".Statistiques.public.lu.Archivedfrom the original on 23 March 2015.Retrieved2 April2015.

- ^Data refer mostly to the year 2011.World Economic Outlook Database-April 2012Archived26 October 2012 at theWayback Machine,International Monetary Fund.Accessed on 18 April 2012.

- ^"GDP per capita in PPS".ec.europa.eu/eurostat.Eurostat.Archivedfrom the original on 20 January 2015.Retrieved18 June2020.

- ^"2011 Index of Economic Freedom".The Heritage FoundationandThe Wall Street Journal.Archived fromthe originalon 29 June 2013.Retrieved15 January2011.

- ^"World Life Quality Index 2005"(PDF).Economist Intelligence Unit. 2005.Archived(PDF)from the original on 2 August 2012.Retrieved23 July2006.

- ^Dutta, Soumitra; Lanvin, Bruno; Wunsch-Vincent, Sacha; León, Lorena Rivera; World Intellectual Property Organization."Global Innovation Index 2023, 15th Edition".WIPO.doi:10.34667/tind.46596.Archivedfrom the original on 22 October 2023.Retrieved23 October2023.

- ^"Luxembourg makes progress in OECD standards on tax information exchange".OECD. 8 July 2009. Archived fromthe originalon 15 March 2015.Retrieved24 December2011.

- ^"A progress report on the jurisdictions surveyed by the OECD Global Forum"(PDF).OECD. July 2009. Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 21 February 2011.Retrieved3 February2011.

- ^Arlow, Oliver (14 March 2010)."Kim Jong-il $4bn emergency fund in European banks".Telegraph.Archivedfrom the original on 22 May 2018.Retrieved5 April2018.

- ^Griffiths, Ian (4 April 2012)."How one word change lets Amazon pays less tax on its UK activities".The Guardian.London.Archivedfrom the original on 12 August 2016.Retrieved17 December2016.

- ^"Embargo 4 October 0.01 AM Central European Times"(PDF).Financial Secrecy Index. Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 4 April 2015.Retrieved2 April2015.

- ^Bowers, Simon (5 November 2014)."Luxembourg tax files: how tiny state rubber-stamped tax avoidance on an industrial scale".The Guardian.Archivedfrom the original on 26 October 2015.Retrieved12 November2014.

- ^"Agricultural census in Luxembourg".Eurostat.Archivedfrom the original on 25 June 2019.Retrieved20 July2019.

- ^"Gateway to the European market".Trade and Invest.Archivedfrom the original on 10 May 2021.Retrieved4 June2021.

- ^"Major foreign holders of treasury securities".U.S. Department of the Treasury.Archivedfrom the original on 3 February 2011.Retrieved3 February2011.

- ^"What are the problems of geographic attribution for securities holdings and transactions in the TIC system?".U.S. Treasury International Capital (TIC) reporting system.Archivedfrom the original on 11 January 2011.Retrieved3 February2011.

- ^"Luxembourg National Debt 2019".countryeconomy.com.Archivedfrom the original on 30 November 2018.Retrieved27 June2019.

- ^""The miracle of Luxembourg growth has a name, that of frontier"".Le Monde(in French). 17 February 2021.Archivedfrom the original on 14 November 2021.Retrieved13 November2021.

- ^"Longueur du réseau routier".travaux.public.lu(in French).Archivedfrom the original on 29 April 2021.Retrieved27 April2021.

- ^"About Luxembourg Airport".Luxembourg Airport.Archivedfrom the original on 20 December 2022.Retrieved27 April2021.

- ^"Trams return to Luxembourg city centre".International Railway Journal.3 August 2018.Archivedfrom the original on 27 April 2021.Retrieved27 April2021.

- ^"List of countries by vehicles per capita".appsso.eurostat.ec.europa.eu.Archivedfrom the original on 4 December 2022.Retrieved5 November2021.

- ^Calder, Simon (29 February 2020)."Luxembourg makes history as first country with free public transport".The Independent.Archivedfrom the original on 31 December 2020.Retrieved29 February2020.

- ^"Legilux – Réseaux et services de communications électroniques".Legilux.public.lu. Archived fromthe originalon 13 September 2016.Retrieved2 April2015.

- ^"Institut Luxembourgeois de Régulation – Communications électroniques".Ilr.public.lu. Archived fromthe originalon 21 March 2015.Retrieved2 April2015.

- ^"Service des médias et des communications (SMC) – gouvernement.lu // L'actualité du gouvernement du Luxembourg".Mediacom.public.lu. Archived fromthe originalon 20 August 2014.Retrieved2 April2015.

- ^"Study on broadband coverage 2011. Retrieved on 25 January 2013".Archivedfrom the original on 10 May 2013.Retrieved7 October2013.

- ^"Household Download Index. Retrieved on 9 April 2013".Netindex.com. 6 April 2011. Archived fromthe originalon 29 May 2015.Retrieved7 October2013.

- ^"Eurohub Luxembourg – putting Europe at your fingertips"(PDF).Archived from the original on 19 November 2008.Retrieved19 February2010.

{{cite web}}:CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link).Ministry of Economy and Foreign Trade of Luxembourg. August 2008 - ^"Why Luxembourg? – AMCHAM".Archivedfrom the original on 19 December 2019.Retrieved19 December2019.

- ^"Financial express special issue on Luxembourg"(PDF).23 June 2009. Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 30 March 2012.Retrieved13 August2010.

- ^pressinfo (23 February 2010)."Press Release: New ITU report shows global uptake of ICTs increasing, prices falling".Itu.int.Archivedfrom the original on 2 May 2010.Retrieved23 April2010.

- ^"Luxembourg ranks on the top in the ITU ICT survey".[dead link]

- ^"Global Broadband Quality Study".Socsci.ox.ac.uk.Retrieved2 April2015.[permanent dead link]

- ^"Global Broadband Quality Study Shows Progress, Highlights Broadband Quality Gap"(PDF).Said Business School, University of Oxford.Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 12 January 2011.Retrieved13 August2010.

- ^"ams-ix.net".ams-ix.net.Archivedfrom the original on 7 December 2006.Retrieved7 October2013.

- ^"de-cix.net".de-cix.net.Archivedfrom the original on 30 September 2013.Retrieved7 October2013.

- ^"linx.net".linx.net.Archivedfrom the original on 5 October 2013.Retrieved7 October2013.

- ^"ICT Business Environment in Luxembourg".Luxembourgforict.lu. Archived fromthe originalon 25 June 2009.Retrieved13 August2010.

- ^Tom Kettels (15 May 2009)."ICT And E-Business – Be Global from Luxembourg"(PDF).Archived(PDF)from the original on 21 July 2011.Retrieved13 August2010.

- ^"PricewaterhouseCoopers Invest in Luxembourg".Pwc.com. Archived fromthe originalon 12 May 2011.Retrieved13 August2010.

- ^"Why Luxembourg? A highly strategic position in the heart of Europe".teralink.lu. Archived fromthe originalon 11 May 2011.Retrieved13 August2010.

- ^"ITU-T ICT Statistics: Luxembourg".Itu.int. Archived fromthe originalon 5 July 2016.Retrieved13 August2010.

- ^"Telx Partners with German Hub Provider ancotel to Provide Virtual Connections between U.S. and Europe"(PDF).Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 21 February 2011.Retrieved13 August2010.

- ^"Globale Rechenzentren | Colocation mit niedrigen Latenzen für Finanzunternehmen, CDNs, Enterprises & Cloud-Netzwerke bei Equinix"(in German). Ancotel.de. Archived fromthe originalon 15 March 2011.Retrieved2 April2015.

- ^"Ancotel – Telecommunication Operator References".Ancotel.de. Archived fromthe originalon 7 February 2007.Retrieved13 August2010.