Fern Shaffer

Fern Shaffer | |

|---|---|

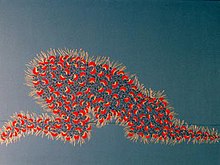

Fern Shaffer, performing Winter Solstice at Lake Michigan, © 1985 | |

| Born | 1944 Chicago, Illinois, US |

| Education | Columbia College Chicago, University of Illinois at Chicago |

| Known for | Painting, Performance Art |

| Movement | Environmental art, Ecofeminism |

| Website | Fern Shaffer |

Fern Shaffer (born 1944) is an American painter, performance artist, lecturer and environmental advocate. Her work arose in conjunction with an emerging Ecofeminism movement that brought together environmentalism, feminist values and spirituality to address shared concern for the Earth and all forms of life.[1] She first gained widespread recognition for a four-part, shamanistic performance cycle, created in collaboration with photographer Othello Anderson in 1985. Writer and critic Suzi Gablik praised their work for its rejection of the technocratic, rationalizing mindset of modernity, in favor of communion with magic, the mysterious and primordial, and the soul.[2] Gablik featured Shaffer's Winter Solstice (1985) as the cover art for her influential book, The Reenchantment of Art, and wrote that the ritual opened "a lost sense of oneness with nature and an acute awareness of ecosystem" that offered "a possible basis for reharmonizing our out-of-balance relationship with nature."[3]

Shaffer is also known for feminist and ecology-themed paintings that critics have described as romantic, dizzying and panoramic,[4] spiritual,[5] and capable of combining the scientific, personal and universal.[6] She has been a long-time activist for women in art through her involvement and leadership at the Chicago alternative art space Artemisia Gallery and work with the national Women's Caucus for Art. In addition to exhibiting work throughout the U.S. and internationally, Shaffer has been active as an arts administrator, public lecturer, and educator.[7]

Life

[edit]Born in Chicago, Shaffer studied art locally, earning a BFA from University of Illinois at Chicago in 1981. She followed with postgraduate work there and at Art Institute of Chicago, before earning an MA in Interdisciplinary Arts from Columbia College Chicago in 1991. In the early 1970s, Shaffer was part of a group of emerging women artists, including Barbara Blades, Carol Diehl, Elizabeth Langer and Sandra Perlow, who studied with painter Corey Postiglione at Evanston Art Center.[8] Blades, Perlow and Shaffer would later be key contributors at Artemisia Gallery.[9]

In the mid-1980s, Shaffer received increasing attention for her painting, and particularly, her performance rituals, with exhibits throughout the U.S. and in Colombia, Germany, Israel, Italy and the United Kingdom. Her work has been featured at institutions including Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago ("Art in Chicago: 1945–1995" survey), Portland Art Museum, Shedd Aquarium, and in solo shows at Peggy Notebaert Nature Museum, Bogotá Museum of Modern Art, and Medellín Museum of Modern Art.[10] Shaffer has received awards from the Andrea Frank Foundation (2000), Nancy H. Gray Foundation for Art in the Environment (1999), and International Friends of Transformative Art (1992).[10][11]

In addition to her work as an artist, Shaffer has served on the advisory board of New Art Examiner, as Program Director of Humanitas Institute in Chicago, and as a chairwoman in that city's Department of Cultural Affairs. For the past 25 years, she has been Program Director at Selfhelp Home, a senior living community originally founded to help refugees and survivors of the Holocaust find community and rebuild their lives.[12]

Work

[edit]Shaffer has worked in a wide range of media, including painting and drawing, sculpture, installation and performance, most frequently addressing themes of the body, gender, nature and ecology, and the intersections between them.

Painting

[edit]

In her early work, Shaffer painted in a minimalist, abstract style influenced by artists such as Barnett Newman. Her first solo show, Ontology at 36 (1981), however, marked a shift that would continue, toward experimentation with mixed materials, representational elements such as the figure, landscape or symbolic imagery, and more emphatic themes. The "Morphogenic Fields" series (1983)—its title referencing the aura of radiation that emanates from living beings—features the female form, rendered in soul-baring, tenuous outline. Shaffer uses a shifting figure/ground relationship calling to mind the flow of energy in, out and through us, depicting women enveloped within fields of gestural DNA-like marks or packed with radiating color strokes like bursts of energy set against darker voids. Evoking both the personal and universal, these works address women's identity on the threshold of exploring, and perhaps realizing, the possibilities for fulfillment opened up by feminism.[6]

The monumental paintings of Shaffer's Greenhouse Effect exhibition (1991) demonstrate a shift in theme, as she employed minimal color-fields to suggest haunted landscapes affected by eco-devastation.[13] Describing them, critic Michelle Grabner wrote, "This ecological commentary combined with Shaffer's choice of scale, interest in color, and seductive mark making evokes the ‘tainted sublime.'"[4] In her "Healing Plants" works (1994–Present), in works such as Aloe, Lungwort or Gingko (1994), Shaffer combines "careful study, connection and fine draftsmanship" to create "portraits" of plants that echo Matisse cutouts, and which convey and pay tribute to the endurance, healing powers, and necessity of plants to human survival.[5] Shaffer's recent paintings, Passenger Pigeons, reflect on the extinction of wildlife species in the modern era.[10]

Performance & Ritual Works

[edit]In 1980, inspired by her interest in Edgar Cayce, Mircea Eliade and Michael Harner, and prompted by ecological concerns shared with her collaborator Othello Anderson, Shaffer began enacting self-designed shamanistic rituals as a form of spiritual intervention.[14] Anderson documented the rituals in sequential photographs that were later exhibited with elements (ceremonial garments and objects) from the performances.[15] Feminist art critic Gloria Feman Orenstein situated Shaffer's work as part of an emerging Ecofeminism movement, describing the rituals as introducing "feminist matristic resonances" intended to create connections and restoration in the sites and communities within which they are enacted.[16] According to Suzi Gablik, Shaffer's "process of creating a shamanic outfit to wear can be likened to creating a cocoon, or alchemical vessel, a contained place within which magical transformations can take place."[17][18] Art critic Thomas McEvilley related the garments to "an earth mother or fertility-goddess motif," evoking "non-Western or non-Modern identities" in the service of ecological concern.[19] The artists describe the rituals in terms of "energy and thought centered on the equal balance and harmony between Nature, science, and spirit," connecting with the Earth as a living entity whose energy can be reached and unblocked through ritual, prayer and touch, much like acupuncture works on the human body.[20][21]

The first performance cycle included four rituals, one for each solstice: Winter Solstice (1985, at the shores of Lake Michigan); Spiral Dance (1986, at Cahokia Woodhenge, the site of an ancient solar calendar); Forest Cure (1986); and Medicine Wheel (1986). Critic Margaret Hawkins wrote that the "primitive costume and reliance on natural cycles" creates "a mystical, almost pantheistic feel" expressing a "reassuring respect for the ineffable."[22] According to New Art Examiner's Garrett Holg, the cycle "examines the distinctions ‘modern' civilization makes between science and myth, between fact and imagination," while its "displayed objects, like ‘ethnological artifacts' have a powerful and iconographic presence."[23]

Shaffer and Anderson staged later rituals at a beach in the shadow of an Indiana nuclear plant, Big Sur, and in the case of the cycle Urban Series (1991), uncharacteristic, litter-strewn, urban vacant lots and rubbish heaps.[11] For those three rituals, designed to initiate environmental healing by evoking archaic mystery and connection, Shaffer donned a garment pointedly fabricated from bubble wrap and other refuse.[24][25] Between 1995–2003, the artists created Nine Year Ritual, a cycle of annual healing ceremonies enacted at sites affected by mining, the greenhouse effect or waste material accumulation, including Death Valley, Temagami Island, the head waters of the Mississippi River, Green Point, Newfoundland, and the Cache River Basin Wetlands. In 2015, the documented rituals comprised an exhibition at Chicago's Peggy Notebaert Nature Museum.[5]

Feminism & Artemisia Gallery

[edit]Shaffer worked on issues involving women and art for many years. She was a member and president (1982-1992) of the alternative art space Artemisia Gallery, one of the first women artist collaboratives in the U.S., which was founded in Chicago in 1973 by a group that included Phyllis Bramson, Vera Klement, Susan Michod and Margaret Wharton.[26][27][28] During Shaffer's leadership, the gallery featured exhibitions and lectures by Eleanor Antin, Judy Chicago, Ann Hamilton, Barbara Kruger, Betye Saar, Pat Steir and Joan Truckenbrod, as well as discussions with authors and artists such as Vito Acconci, Carol Becker, Suzi Gablik, and Thomas McEvilley.[9][29] In addition to her work with Artemisia, Shaffer served on the National Board of Directors for the Women's Caucus for Art (1991-2). In 2003, she was named to the Honor Roll of Feminist Artists by the Veteran Feminists of America, an organization that honors and preserves the history of the accomplishments of women and men in the feminist movement.[30]

Shaffer has lectured on topics including feminist and environmental art, ritual, and alternative art spaces at the Art Institute of Chicago, Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago, Illinois National Organization for Women (NOW) Conference, Midwest Sociologists for Women in Society, University of Wisconsin, Women's Caucus for Art National Conference,[31] the Embassy of the United States Tel Aviv and the Israeli Ministry of Foreign Office, Medellín Museum of Modern Art, and Kalamazoo Institute of Arts, among others. She continues to live and work in Chicago.

External links

[edit]- Fern Shaffer, official website

- Smithsonian Archives of American Art, Fern Shaffer papers

- Clara Database of Women Artists, Fern Shaffer Archived 2018-03-16 at the Wayback Machine

References

[edit]- ^ Diamond, Irene and Gloria Feman Orenstein, Ed. Reweaving the World: The Emergence of Ecofeminism, San Francisco: Sierra Club Books, 1990. Retrieved March 3, 2018.

- ^ Morgan, David. "Enchantment, Disenchantment, Re-Enchantment," in Re-Enchantment, edited by James Elkins, David Morgan. New York: Routledge, 2009, p. 16. Retrieved February 22, 2018.

- ^ Gablik, Suzi. The Reenchantment of Art. London: Thames and Hudson, 1992, p. 45. ISBN 978-0-5002768-9-1. Retrieved February 22, 2018.

- ^ a b Grabner, Michelle. Review, New Art Examiner, September 1991, Vol. 19, No. 1, p. 38.

- ^ a b c Markovich, Annie. "Fern Shaffer at 116 Gallery," New Art Examiner, Vol. 32, No. 2, November/December 2017, p33. Retrieved February 22, 2018.

- ^ a b O'Brien, Patricia. Review, New Art Examiner, Summer 1983, p. 17.

- ^ Archives of American Art entry, Fern Shaffer.[1] Retrieved February 17, 2018.

- ^ Isaacs, Deanna (February 26, 2004)."Postiglione's Women". Chicago Reader. Retrieved February 16, 2018.

- ^ a b Artemisia Gallery. Twentieth Anniversary 1973–1993. Chicago: Artemisia Gallery, 1994.

- ^ a b c Fern Shaffer website.[2] Retrieved February 21, 2018.

- ^ a b International Friends of Transformative Art. "Award Winners 1992 Catalogue," Eva Jungermann, Ed., 1992.

- ^ Selfhelp Home website.[3] Retrieved February 16, 2018.

- ^ McCracken, David. (May 24, 1991). Review, Chicago Tribune, Sect. 7, p. 56.

- ^ Griffin, David Ray. Sacred Interconnections: Postmodern Spirituality, Political Economy, and Art, New York: SUNY Series in Constructive Postmodern Thought, 1991.

- ^ Museum of Contemporary Art, ed. Lynne Warren. Art in Chicago 1945-1995. New York: Thames and Hudson, 1996, p. 243. Retrieved February 22, 2018.

- ^ Orenstein, Gloria Feman. "Artists as Healers: Envisioning Life-Giving Culture," In Reweaving the World: The Emergence of Ecofeminism, Irene Diamond and Gloria Feman Orenstein, Ed., San Francisco: Sierra Club Books, 1990, p. 284.

- ^ Gablik, Suzi. "Learning to Dream," Psychological Perspectives, Fall-Winter 1988, Vol. 19, No. 2, p. 286.

- ^ Perlmutter, Dawn and Koppman, Debra. Reclaiming the Spiritual in Art: Contemporary Cross-Cultural Perspectives, New York: SUNY Press, 2016.

- ^ McEvilley, Thomas. "The Selfhood of the Other: Reflections of a Westerner on the Occasion of an Exhibition of Contemporary Art from Africa." in Africa Explores: 20th century African art, ed. Susan Vogel. New York: Center for African Art, 1991.

- ^ Gablik, Suzi. "The Ecological Imperative, An Interview with Fern Shaffer and Othello Anderson," Art Papers, Nov. 1991.

- ^ Oakes, Baile. Sculpting with the Environment. New York: Van Reinhold, 1995, p. 92. Retrieved February 22, 2018.

- ^ Hawkins, Margaret. (October 31, 1986). "Performance art celebrates seasons," Chicago Sun-Times, p. 37.

- ^ Holg, Garrett. "Fern Shaffer and Othello Anderson," New Art Examiner, December 1986.

- ^ Holg, Garrett. "Othello Anderson Fern Shaffer," Art News, January 1992, Vol. 91, No. 1, p.135.

- ^ Gablik, Suzi. "The Ecological Imperative: Making Art as if the World Mattered," Michigan Quarterly Review, Spring 1993, Vol. XXXII, No. 2, p. 232-4. Retrieved February 22, 2018.

- ^ Artemisia Gallery. Ten Years 1973–1983. Chicago: Artemisia Gallery, 1984. Retrieved February 22, 2018.

- ^ Seaman, Donna. (February 28, 1999)."A Collaborative Art," Chicago Tribune. Retrieved February 22, 2018.

- ^ Nordhaus-Bike, Anne M. "The state of Chicago's galleries," Gazette Chicago, 1997.

- ^ McCracken David. (October 28, 1988)."Art, Events Prove Feminism Alive and Well," Chicago Tribune. Retrieved February 21, 2018.

- ^ Veteran Feminists of America, Mission statement.[4] Retrieved February 17, 2018.

- ^ Shaffer, Fern. "Suzi Gablik," Archived 2014-12-29 at the Wayback Machine Women's Caucus for Art Honor Awards for Outstanding Achievement in the Visual Arts, 2003, p. 10-13.

- 21st-century American painters

- Painters from Chicago

- Environmental artists

- American performance artists

- Women performance artists

- American feminist artists

- 20th-century American painters

- 20th-century American women painters

- 21st-century American women painters

- American postmodern artists

- Columbia College Chicago alumni

- University of Illinois Chicago alumni

- 1944 births

- Living people