Libu

| Libu in hieroglyphs | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

rbw | |||||||

The Libu (Ancient Egyptian: rbw; also transcribed Rebu, Libo, Lebu, Lbou, Libou) were an Ancient Libyan tribe of Berber origin, from which the name Libya derives.[1]

Early history

[edit]

Their tribal origin in Ancient Libya is first attested in Egyptian language texts from the New Kingdom, especially from the Ramesside Period. The earliest occurrence is in a Ramesses II inscription.[2] There were no vowels in the Egyptian script. The name Libu is written as rbw in Egyptian hieroglyphs. In the Great Karnak Inscription, the pharaoh Merneptah describes the Libu as men with pale complexion, tattooed, and with dark hair and eyes.[citation needed]

Hostilities between Egypt and Libya broke out in regnal year 5 (1208 BCE), but the coalition of Libu and Sea Peoples led by the chief of the Libu Meryey was defeated.[3][4] Libu appears as an ethnic name on the Merneptah Stele, also known as the Israel Stele.[5]

Ramesses III defeated the Libyans in the 5th year of his reign, but six years later the Libyans joined the Meshwesh and invaded the western Delta and were defeated once again.[6]

This name Libu was taken over by the Greeks of Cyrenaica, who co-existed with them.[7] Geographically, the name of this tribe was adopted by the Greeks for "Cyrenaica" as well as for northwestern Africa in general.[8]

In the neo-Punic inscriptions, Libu was written as Lby for the masculine noun, and Lbt for the feminine noun of Libyan. The name supposedly was used as an ethnic name in those inscriptions.[9]

Great Chiefs of the Libu

[edit]In the Western Nile Delta, some time during the 22nd Dynasty of Egypt flourished a realm of the Libu led by "Great Chiefs of the Libu".[10] Those rulers soon formed a dynasty, and they often had local "Chiefs of the Ma(shuash)" as their subordinates. The dynasty culminated with the chiefdom of Tefnakht who, despite holding both the titles of "Great Chief of the Libu" and of "Chief of the Ma" at Sais, was more probably of Egyptian ethnicity rather than either Libu or Ma.[11] Later, Tefnakht claimed for himself even the pharaonic titles, founding the 24th Dynasty.[12]

Below lists the succession of the known "Great Chiefs of the Libu". They used to date their monuments following the regnal years of the contemporary pharaoh of the 22nd Dynasty.[13]

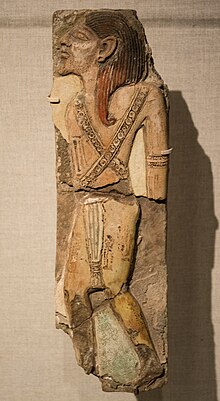

| Name | Image | Attested in regnal year... | Corresponding absolute datation | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inamunnifnebu |  |

Year 31 of Shoshenq III[13] | 795 BCE | - |

| Niumateped |  |

Year 4 of Shoshenq IV Year 8 of Shoshenq IV Year 10 of Shoshenq IV[14] |

- BCE | Possibly two different rulers with the same name |

| Tjerpahati |  |

Year 7 of Shoshenq V Year 15 of Shoshenq V[14] |

760 BCE 753 BCE |

Also known in literature as Tjerper or Titaru, son of Didi |

| Ker |  |

Year 19 of Shoshenq V[13] | 749 BCE | - |

| Rudamun | Year 30 of Shoshenq V[13] | 738 BCE | - | |

| Ankhhor | Year 37 of Shoshenq V Year ? of Shoshenq V[13] |

731 BCE ? BCE |

Struggled against Tefnakht and was likely defeated by him | |

| Tefnakht |  |

Year 36 of Shoshenq V Year 38 of Shoshenq V[13] |

732 BCE 730 BCE |

- |

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Zimmermann, K. (2008). "Lebou/Libou". Encyclopédie berbère. Vol. 28-29 | Kirtēsii – Lutte. Aix-en-Provence: Edisud. pp. 4361–4363. doi:10.4000/encyclopedieberbere.319.

- ^ Clark, Desmond J. (ed.) (1982) "Egypt and Libia" The Cambridge History of Africa: From the earliest times to c. 500 BC volume I, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, England, p. 919, ISBN 0-521-22215-X

- ^ Breasted, James H. (1906) Ancient Records of Egypt, Part Three, Chicago, §§572ff.

- ^ Manassa, Colleen (2003). The Great Karnak Inscription of Merneptah: Grand Strategy in the 13th Century B.C. New Haven: Yale Egyptological Seminar. ISBN 9780974002507.

The seventy-nine line inscription is located on the interior of the east wall of the "Cours De la Cachette," directly north of a copy of the Hittite treaty from the reign of Ramesses II and in conjunction with other reliefs of Merneptah (PM II, p. 131 [486])... Unfortunately, the excavation of the Cours De la Cachette between 1978-1981 by the French expedition at Karnak did not discover any new blocks belonging to the Great Karnak Inscription of Merneptah, although it did demonstrate that the court was filled with many ritual and religious scenes in addition to its known military themes (F. LeSaout, "Reconstitution des murs de la Cours De la Cachette," Cahiers De Karrah VII (1978-1981) [Paris, 1982], p. 214).

- ^ [...] The vile chief of the Libu who fled under cover of night alone without a feather on his head, his feet unshod, his wives seized before his very eyes, the meal for his food taken away, and without water in the water-skin to keep him alive; the faces of his brothers are savage to kill him, his captains fighting one against the other, their camps burnt and made into ashes [...] After Gardiner, Alan Henderson (1964) Egypt of the Pharaohs: an introduction Oxford University Press, London, p. 273, ISBN 0-19-500267-9

- ^ J. H. Breasted, Ancient Records of Egypt, Part Four, Chicago 1906, §§83ff. Afterward, the name appeared repeatedly in other pharaonic records.

- ^ Fage, J. D. (ed.) (1978) "The Libyans" The Cambridge History of Africa: From c. 500 BC to AD 1050 volume II, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, England, p. 141, ISBN 0-521-21592-7

- ^ "Libya". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 2016-11-24.

- ^ Thomas C. Oden (2011). Early Libyan Christianity: Uncovering a North African Tradition. InterVarsity Press. p. 51. ISBN 978-0830869541.

- ^ O'Connor, David. "Egyptians and Libyans in the New Kingdom" Expedition Magazine 29.3. Penn Museum, 1987

- ^ P.R. Del Francia, "Di una statuetta dedicata ad Amon-Ra dal grande capo dei Ma Tefnakht nel Museo Egizio di Firenze", S. Russo (ed.) Atti del V Convegno Nazionale di Egittologia e Papirologia, Firenze, 10-12 dicembre 1999, Firenze, 2000, p. 94

- ^ Kitchen, Kenneth A. (1996). The Third Intermediate Period in Egypt (1100–650 BC). Warminster: Aris & Phillips Limited. ISBN 0-85668-298-5., § 249; 306

- ^ a b c d e f Berlandini, Jocelyne (1978). "Une stèle de donation du dynaste libyen Roudamon". BIFAO. 78: 162.

- ^ a b Jansen-Winkeln, Karl (2014). "Die "Großfürsten der Libu" im westlichen Delta in der späten 22. Dynastie" (PDF). Journal of Egyptian History. 7 (2): 194–202. doi:10.1163/18741665-12340017.