3 Juno

| |

| Discovery | |

|---|---|

| Discovered by | Karl Ludwig Harding |

| Discovery date | 1 September 1804 |

| Designations | |

| (3) Juno | |

| Pronunciation | /ˈdʒuːnoʊ/[1] |

Named after | Juno(Latin:Iūno) |

| Main belt(Juno clump) | |

| Adjectives | Junonian/dʒuːˈnoʊniən/[2] |

| Symbol | |

| Orbital characteristics[3] | |

| Epoch13 September 2023 (JD2453300.5) | |

| Aphelion | 3.35AU(501 millionkm) |

| Perihelion | 1.985 AU (297.0 million km) |

| 2.67 AU (399 million km) | |

| Eccentricity | 0.2562 |

| 4.361yr | |

Averageorbital speed | 17.93 km/s |

| 37.02° | |

| Inclination | 12.991° |

| 169.84° | |

| 2 April 2023 | |

| 247.74° | |

| EarthMOID | 1.04 AU (156 million km) |

| Proper orbital elements[4] | |

Propersemi-major axis | 2.6693661AU |

Propereccentricity | 0.2335060 |

Properinclination | 13.2515192° |

Propermean motion | 82.528181deg/yr |

Properorbital period | 4.36215yr (1593.274d) |

Precession ofperihelion | 43.635655arcsec/yr |

Precession of theascending node | −61.222138arcsec/yr |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Dimensions | (288 × 250 × 225) ± 5 km[5] (320 × 267 × 200) ± 6 km[6] |

| 254±2 km[5] 246.596±10.594 km[3] | |

| Mass | (2.7±0.24)×1019kg[5] (2.86±0.46)×1019kg[7][a] |

Meandensity | 3.15±0.28 g/cm3[5] 3.20±0.56 g/cm3[7] |

Equatorialsurface gravity | 0.112 m/s2(0.0114g0) |

Equatorialescape velocity | 0.168 km/s |

| 7.21 hr[3](0.3004 d)[8] | |

Equatorial rotation velocity | 31.75 m/s[b] |

| 27° ± 5°[9] | |

| 103° ± 5°[9] | |

| 0.202[5] 0.238[3][10] | |

| Temperature | ~163K max:301 K (+28°C)[11] |

| S[3][12] | |

| 7.4[13][14]to 11.55 | |

| 5.33[3][10] | |

| 0.30 "to 0.07" | |

Juno(minor-planet designation:3 Juno) is a largeasteroidin theasteroid belt.Juno was the third asteroid discovered, in 1804, by German astronomerKarl Harding.[15]It is one of thetwenty largest asteroidsand one of the two largest stony (S-type) asteroids, along with15 Eunomia.It is estimated to contain 1% of the total mass of the asteroid belt.[16]

History

[edit]Discovery

[edit]Juno was discovered on 1 September 1804, byKarl Ludwig Harding.[17]It was the thirdasteroidfound, but was initially considered to be aplanet;it was reclassified as an asteroid andminor planetduring the 1850s.[18]

Name and symbol

[edit]Juno is named after the mythologicalJuno,the highest Roman goddess. The adjectival form is Junonian (from Latinjūnōnius), with the historical finalnof the name (still seen in the French form,Junon) reappearing, analogous to Pluto ~ Plutonian.[2] 'Juno' is the international name for the asteroid, subject to local variation: ItalianGiunone,FrenchJunon,RussianЮнона(Yunona), etc.[c]

The oldastronomical symbolof Juno, still used in astrology, is a scepter topped by a star,⟨![]() ⟩.There were many graphic variants with a more elaborated scepter, such as

⟩.There were many graphic variants with a more elaborated scepter, such as![]() ,sometimes tilted at an angle to provide more room for decoration.

The generic asteroid symbol of a disk with its discovery number,⟨③⟩,was introduced in 1852 and quickly became the norm.[19][20]The scepter symbol was resurrected for astrological use in 1973.[21]

,sometimes tilted at an angle to provide more room for decoration.

The generic asteroid symbol of a disk with its discovery number,⟨③⟩,was introduced in 1852 and quickly became the norm.[19][20]The scepter symbol was resurrected for astrological use in 1973.[21]

Characteristics

[edit]Juno is one of the larger asteroids, perhaps tenth by size and containing approximately 1% the mass of the entireasteroid belt.[22]It is the second-most-massive S-type asteroid after 15 Eunomia.[6]Even so, Juno has only 3% the mass ofCeres.[6]The orbital period of Juno is 4.36578 years.[23]

Amongst S-type asteroids, Juno is unusually reflective, which may be indicative of distinct surface properties. This high albedo explains its relatively highapparent magnitudefor a small object not near the inner edge of the asteroid belt. Juno can reach +7.5 at a favourable opposition, which is brighter thanNeptuneorTitan,and is the reason for it being discovered before the larger asteroidsHygiea,Europa,Davida,andInteramnia.At most oppositions, however, Juno only reaches a magnitude of around +8.7[24]—only just visible withbinoculars—and at smallerelongationsa 3-inch (76 mm)telescopewill be required to resolve it.[25]It is the main body in theJuno family.

Juno was originally considered a planet, along with1 Ceres,2 Pallas,and4 Vesta.[26]In 1811,Schröterestimated Juno to be as large as 2290 km in diameter.[26]All four were reclassified as asteroids as additional asteroids were discovered. Juno's small size and irregular shape preclude it from being designated adwarf planet.

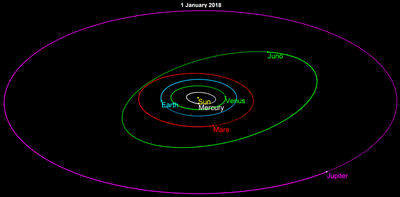

Juno orbits at a slightly closer mean distance to theSunthan Ceres or Pallas. Its orbit is moderately inclined at around 12° to theecliptic,but has an extremeeccentricity,greater than that ofPluto.This high eccentricity brings Juno closer to the Sun atperihelionthan Vesta and further out ataphelionthan Ceres. Juno had the most eccentric orbit of any known body until33 Polyhymniawas discovered in 1854, and of asteroids over 200 km in diameter only324 Bambergahas a more eccentric orbit.[27]

Juno rotates in aprogradedirection with anaxial tiltof approximately 50°.[9]The maximum temperature on the surface, directly facing the Sun, was measured at about 293Kon 2 October 2001. Taking into account theheliocentricdistance at the time, this gives an estimated maximum temperature of 301 K (+28 °C) at perihelion.[11]

Spectroscopic studies of the Junonian surface permit the conclusion that Juno could be the progenitor ofchondrites,a common type of stonymeteoritecomposed of iron-bearingsilicatessuch asolivineandpyroxene.[28]Infraredimages reveal that Juno possesses an approximately 100 km-wide crater or ejecta feature, the result of a geologically young impact.[29][30]

Based on MIDAS infrared data using theHale Telescope,an average radius of 135.7±11 was reported in 2004.[31]

Observations

[edit]Juno was the first asteroid for which anoccultationwas observed. It passed in front of a dimstar(SAO 112328) on 19 February 1958. Since then, several occultations by Juno have been observed, the most fruitful being the occultation ofSAO 115946on 11 December 1979, which was registered by 18 observers.[32] Juno occulted the magnitude 11.3 starPPMX 9823370on 29 July 2013,[33]and2UCAC 30446947on 30 July 2013.[34]

Radio signals from spacecraft in orbit aroundMarsand on its surface have been used to estimate the mass of Juno from the tiny perturbations induced by it onto the motion of Mars.[35]Juno'sorbitappears to have changed slightly around 1839, very likely due to perturbations from a passing asteroid, whose identity has not been determined.[36]

In 1996, Juno was imaged by theHooker TelescopeatMount Wilson Observatoryat visible and near-IR wavelengths, usingadaptive optics.The images spanned a whole rotation period and revealed an irregular shape and a dark albedo feature, interpreted as a fresh impact site.[30]

-

Juno seen at four wavelengths with a largecraterin the dark (Hooker telescope,2003

-

Juno moving across background stars

-

Juno during opposition in 2009

-

Video of Juno taken as part of ALMA's Long Baseline Campaign

Oppositions

[edit]Juno reachesoppositionfrom the Sun every 15.5 months or so, with its minimum distance varying greatly depending on whether it is near perihelion or aphelion. Sequences of favorable oppositions occur every 10th opposition, i.e. just over every 13 years. The last favorable oppositions were on 1 December 2005, at a distance of 1.063 AU, magnitude 7.55, and on 17 November 2018, at a minimum distance of 1.036 AU, magnitude 7.45.[37][38]The next favorable opposition will be 30 October 2031, at a distance of 1.044 AU, magnitude 7.42.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^(1.44 ± 0.23)×10−11M☉

- ^Calculated based on the known parameters

- ^There are two exceptions: Greek, where the name was translated to its Hellenic equivalent,Hera(3 Ήρα), as in the cases of1 Ceresand4 Vesta;and Chinese, where it is called the 'marriage-god(dess) star' ( hôn thần tinhhūnshénxīng). This contrasts with the goddess Juno, for which Chinese uses the transliterated Latin name ( Juneauzhūnuò).

References

[edit]- ^"Juno".Dictionary Unabridged(Online). n.d.

- ^ab"Junonian".Oxford English Dictionary(Online ed.).Oxford University Press.(Subscription orparticipating institution membershiprequired.)

- ^abcdef"JPL Small-Body Database Browser: 3 Juno"(2017-11-26 last obs).Archivedfrom the original on 5 January 2016.Retrieved17 November2014.

- ^"AstDyS-2 Juno Synthetic Proper Orbital Elements".Department of Mathematics, University of Pisa, Italy.Archivedfrom the original on 9 July 2021.Retrieved1 October2011.

- ^abcdeP. Vernazza et al. (2021) VLT/SPHERE imaging survey of the largest main-belt asteroids: Final results and synthesis.Astronomy & Astrophysics54, A56

- ^abc Baer, Jim (2008)."Recent Asteroid Mass Determinations".Personal Website. Archived fromthe originalon 2 July 2013.Retrieved3 December2008.

- ^abJames Baer, Steven Chesley & Robert Matson (2011) "Astrometric masses of 26 asteroids and observations on asteroid porosity."The Astronomical Journal,Volume 141, Number 5

- ^ Harris, A. W.; Warner, B. D.; Pravec, P., eds. (2006)."Asteroid Lightcurve Derived Data. EAR-A-5-DDR-DERIVED-LIGHTCURVE-V8.0".NASA Planetary Data System.Archived fromthe originalon 9 April 2009.Retrieved15 March2007.

- ^abcThe north pole points towardsecliptic coordinates(β, λ) = (27°, 103°) within a 5° uncertainty. Kaasalainen, M.; Torppa, J.; Piironen, J. (2002)."Models of Twenty Asteroids from Photometric Data"(PDF).Icarus.159(2): 369–395.Bibcode:2002Icar..159..369K.doi:10.1006/icar.2002.6907.Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 16 February 2008.Retrieved30 November2005.

- ^ab Davis, D. R.; Neese, C., eds. (2002)."Asteroid Albedos. EAR-A-5-DDR-ALBEDOS-V1.1".NASA Planetary Data System.Archived fromthe originalon 17 December 2009.Retrieved18 February2007.

- ^ab Lim, Lucy F.; McConnochie, Timothy H.; Bell, James F.; Hayward, Thomas L. (2005). "Thermal infrared (8–13 μm) spectra of 29 asteroids: the Cornell Mid-Infrared Asteroid Spectroscopy (MIDAS) Survey".Icarus.173(2): 385–408.Bibcode:2005Icar..173..385L.doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2004.08.005.

- ^Neese, C., ed. (2005)."Asteroid Taxonomy.EAR-A-5-DDR-TAXONOMY-V5.0".NASA Planetary Data System.Archived fromthe originalon 5 September 2006.Retrieved24 December2013.

- ^"AstDys (3) Juno Ephemerides".Department of Mathematics, University of Pisa, Italy.Archivedfrom the original on 9 July 2021.Retrieved26 June2010.

- ^"Bright Minor Planets 2005".Minor Planet Center.Archived fromthe originalon 29 September 2008.

- ^Cunningham, Clifford J (2017),Bode's Law and the discovery of Juno: historical studies in asteroid research,Springer,ISBN978-3-319-32875-1

- ^ Pitjeva, E. V.(2005)."High-Precision Ephemerides of Planets—EPM and Determination of Some Astronomical Constants"(PDF).Solar System Research.39(3): 176.Bibcode:2005SoSyR..39..176P.doi:10.1007/s11208-005-0033-2.S2CID120467483.Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 31 October 2008.

- ^Cunningham, Clifford J.(2017). "The Discovery of Juno".Bode's Law and the Discovery of Juno.Historical Studies in Asteroid Research.Springer Publishing.p. 37.doi:10.1007/978-3-319-32875-1.ISBN978-3-319-32875-1.

- ^Hilton, James L."When did the asteroids become minor planets?".U.S. Naval Observatory.Archived fromthe originalon 24 March 2008.Retrieved8 May2008.

- ^Forbes, Eric G. (1971)."Gauss and the Discovery of Ceres".Journal for the History of Astronomy.2(3): 195–199.Bibcode:1971JHA.....2..195F.doi:10.1177/002182867100200305.S2CID125888612.Archivedfrom the original on 18 July 2021.Retrieved18 July2021.

- ^Gould, B. A.(1852). "On the symbolic notation of the asteroids".Astronomical Journal.2(34): 80.Bibcode:1852AJ......2...80G.doi:10.1086/100212.

- ^Eleanor Bach (1973)Ephemerides of the asteroids: Ceres, Pallas, Juno, Vesta, 1900–2000.Celestial Communications.

- ^Pitjeva, E. V.;Precise determination of the motion of planets and some astronomical constants from modern observationsArchived14 December 2023 at theWayback Machine,in Kurtz, D. W. (Ed.),Proceedings of IAU Colloquium No. 196: Transits of Venus: New Views of the Solar System and Galaxy,2004

- ^"Comets Asteroids".Find The Data.org. Archived fromthe originalon 14 May 2014.Retrieved14 May2014.

- ^ Odeh, Moh'd."The Brightest Asteroids".The Jordanian Astronomical Society. Archived fromthe originalon 11 May 2008.Retrieved21 May2008.

- ^ "What Can I See Through My Scope?".Ballauer Observatory. 2004. Archived fromthe originalon 26 July 2011.Retrieved20 July2008.(archived)

- ^ab Hilton, James L(16 November 2007)."When did asteroids become minor planets?".U.S. Naval Observatory.Archived fromthe originalon 24 March 2008.Retrieved22 June2008.

- ^"MBA Eccentricity Screen Capture".JPL Small-Body Database Search Engine. Archived fromthe originalon 27 March 2009.Retrieved1 November2008.

- ^ Gaffey, Michael J.; Burbine, Thomas H.; Piatek, Jennifer L.; Reed, Kevin L.; Chaky, Damon A.; Bell, Jeffrey F.; Brown, R. H. (1993). "Mineralogical variations within the S-type asteroid class".Icarus.106(2): 573.Bibcode:1993Icar..106..573G.doi:10.1006/icar.1993.1194.

- ^ "Asteroid Juno Has A Bite Out Of It".Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics. 6 August 2003. Archived fromthe originalon 8 February 2007.Retrieved18 February2007.

- ^abBaliunas, Sallie; Donahue, Robert; Rampino, Michael R.; Gaffey, Michael J.; Shelton, J. Christopher; Mohanty, Subhanjoy (2003)."Multispectral analysis of asteroid 3 Juno taken with the 100-inch telescope at Mount Wilson Observatory"(PDF).Icarus.163(1): 135–141.Bibcode:2003Icar..163..135B.doi:10.1016/S0019-1035(03)00049-6.Archived(PDF)from the original on 23 January 2023.Retrieved18 July2017.

- ^Lim, L; McConnochie, T; Belliii, J; Hayward, T (2005)."Thermal infrared (8?13?m) spectra of 29 asteroids: The Cornell Mid-Infrared Asteroid Spectroscopy (MIDAS) Survey"(PDF).Icarus.173(2): 385.Bibcode:2005Icar..173..385L.doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2004.08.005.Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 3 March 2016.Retrieved26 August2019.

- ^Millis, R. L.; Wasserman, L. H.; Bowell, E.; Franz, O. G.; White, N. M.; Lockwood, G. W.; Nye, R.; Bertram, R.; et al. (February 1981)."The diameter of Juno from its occultation of AG+0°1022"(PDF).Astronomical Journal.86:306–313.Bibcode:1981AJ.....86..306M.doi:10.1086/112889.Archivedfrom the original on 14 December 2023.Retrieved4 September2019.

- ^Asteroid Occultation Updates – 29 Jul 2013

- ^Asteroid Occultation Updates – 30 Jul 2013.

- ^ Pitjeva, E. V. (2004). "Estimations of masses of the largest asteroids and the main asteroid belt from ranging to planets, Mars orbiters and landers".35th COSPAR Scientific Assembly. Held 18–25 July 2004, in Paris, France.p. 2014.Bibcode:2004cosp...35.2014P.

- ^Hilton, James L. (February 1999)."US Naval Observatory Ephemerides of the Largest Asteroids".Astronomical Journal.117(2): 1077–1086.Bibcode:1999AJ....117.1077H.doi:10.1086/300728.

- ^The Astronomical Almanac for the year 2018, G14

- ^Asteroid 3 Juno at oppositionArchived1 December 2017 at theWayback Machine16 Nov 2018 at 11:31 UTC

External links

[edit]- JPL Ephemeris

- Well resolved images from four anglestaken atMount Wilson observatory

- Shape model deduced from light curve

- Asteroid Juno Grabs the Spotlight

- "Elements and Ephemeris for (3) Juno".Minor Planet Center. Archived fromthe originalon 4 September 2015.(displaysElongfrom Sun andV magfor 2011)

- 3 JunoatAstDyS-2, Asteroids—Dynamic Site

- 3 Junoat theJPL Small-Body Database