Zaire ebolavirus

| Zaire ebolavirus | |

|---|---|

| |

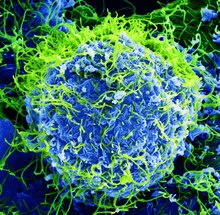

| Colorized scanning electron micrograph of Ebola virus particles (green) found both as extracellular particles and budding particles from a chronically infected African Green Monkey Kidney cell (blue); 20,000x magnification | |

| Virus classification | |

| (unranked): | Virus |

| Realm: | Riboviria |

| Kingdom: | Orthornavirae |

| Phylum: | Negarnaviricota |

| Class: | Monjiviricetes |

| Order: | Mononegavirales |

| Family: | Filoviridae |

| Genus: | Ebolavirus |

| Species: | Zaire ebolavirus

|

Zaire ebolavirus,more commonly known asEbola virus(/iˈboʊlə,ɪ-/;EBOV), is one of six known species within thegenusEbolavirus.[1]Four of the six known ebolaviruses, including EBOV, cause a severe and often fatalhemorrhagic feverinhumansand othermammals,known asEbola virus disease(EVD). Ebola virus has caused the majority of human deaths from EVD, and was the cause of the2013–2016 epidemic in western Africa,[2]which resulted in at least 28,646 suspected cases and 11,323 confirmed deaths.[3][4]

Ebola virus and its genus were both originally named forZaire(now theDemocratic Republic of the Congo), the country where it wasfirst described,[1]and was at first suspected to be a new "strain" of the closely relatedMarburg virus.[5][6]The virus was renamed "Ebola virus" in 2010 to avoid confusion. Ebola virus is the single member of thespeciesZaire ebolavirus,which is assigned to the genusEbolavirus,familyFiloviridae,orderMononegavirales.The members of the species are called Zaire ebolaviruses.[1][7]The natural reservoir of Ebola virus is believed to bebats,particularlyfruit bats,[8]and it is primarily transmitted between humans and from animals to humans throughbody fluids.[9]

The EBOV genome is a single-stranded RNA, approximately 19,000nucleotideslong. It encodes seven structuralproteins:nucleoprotein(NP),polymerase cofactor(VP35), (VP40), GP,transcription activator(VP30),VP24,andRNA-dependent RNA polymerase(L).[10]

Because of its highfatality rate(up to 83 to 90 percent),[11][12]EBOV is also listed as aselect agent,World Health OrganizationRisk Group 4 Pathogen (requiringBiosafety Level 4-equivalent containment), a USNational Institutes of Health/National Institute of Allergy and Infectious DiseasesCategory A Priority Pathogen, US CDCCenters for Disease Control and PreventionCategory A Bioterrorism Agent,and a Biological Agent for Export Control by theAustralia Group.[citation needed]

Structure

[edit]

EBOV carries anegative-senseRNA genome in virions that are cylindrical/tubular, and containviral envelope,matrix, and nucleocapsid components. The overall cylinders are generally approximately 80nmin diameter, and have a virally encodedglycoprotein(GP) projecting as 7–10 nm long spikes from its lipid bilayer surface.[13]The cylinders are of variable length, typically 800 nm, but sometimes up to 1000 nm long. The outerviral envelopeof the virion is derived by budding from domains of host cell membrane into which the GP spikes have been inserted during their biosynthesis. Individual GP molecules appear with spacings of about 10 nm. Viral proteinsVP40and VP24 are located between the envelope and the nucleocapsid (see following), in thematrix space.[14]At the center of the virion structure is thenucleocapsid,which is composed of a series of viral proteins attached to an 18–19 kb linear, negative-sense RNA without 3′-polyadenylationor 5′-capping (see following); the RNA is helically wound and complexed with the NP, VP35, VP30, and L proteins; this helix has a diameter of 80 nm.[15][16][17]

The overall shape of the virions after purification and visualization (e.g., byultracentrifugationandelectron microscopy,respectively) varies considerably; simple cylinders are far less prevalent than structures showing reversed direction, branches, and loops (e.g., U-,shepherd's crook-, 9-, oreye bolt-shapes, or other or circular/coiled appearances), the origin of which may be in the laboratory techniques applied.[18][19]The characteristic "threadlike" structure is, however, a more general morphologic characteristic of filoviruses (alongside their GP-decorated viral envelope, RNA nucleocapsid, etc.).[18]

Genome

[edit]Each virion contains one molecule of linear, single-stranded, negative-sense RNA, 18,959 to 18,961 nucleotides in length.[20]The 3′ terminus is not polyadenylated and the 5′ end is not capped. This viral genome codes for seven structural proteins and one non-structural protein. The gene order is 3′ – leader – NP – VP35 – VP40 – GP/sGP – VP30 – VP24 – L – trailer – 5′; with the leader and trailer being non-transcribed regions, which carry important signals to control transcription, replication, and packaging of the viral genomes into new virions. Sections of the NP, VP35 and the L genes from filoviruses have been identified as endogenous in the genomes of several groups of small mammals.[21][22][23]

It was found that 472 nucleotides from the 3' end and 731 nucleotides from the 5' end are sufficient for replication of a viral "minigenome", though not sufficient for infection.[18]Virus sequencing from 78 patients with confirmed Ebola virus disease, representing more than 70% of cases diagnosed in Sierra Leone from late May to mid-June 2014,[24][25]provided evidence that the 2014 outbreak was no longer being fed by new contacts with its natural reservoir. Usingthird-generation sequencingtechnology, investigators were able to sequence samples as quickly as 48 hours.[26]Like other RNA viruses,[24]Ebola virus mutates rapidly, both within a person during the progression of disease and in the reservoir among the local human population.[25]The observed mutation rate of 2.0 x 10−3substitutions per site per year is as fast as that of seasonalinfluenza.[27]

| Symbol | Name | UniProt | Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| NP | Nucleoprotein | P18272 | Wraps genome for protection from nucleases and innate immunity. |

| VP35 | Polymerase cofactor VP35 | Q05127 | Polymerase cofactor; suppresses innate immunity by binding RNA. |

| VP40 | Matrix protein VP40 | Q05128 | Matrix. |

| GP | Envelope glycoprotein | Q05320 | Cleaved by host furin into GP1/2 to form envelope with spikes. Also makes shed GP as a decoy. |

| sGP | Pre-small/secreted glycoprotein | P60170 | Shares ORF with GP. Cleaved by host furin into sGP (anti-inflammatory) and delta-peptide (viroporin). |

| ssGP | Super small secreted glycoprotein | Q9YMG2 | Shares ORF with GP; created by mRNA editing. Unknown function. |

| VP30 | Hexameric zinc-finger protein VP30 | Q05323 | Transcriptional activator. |

| VP24 | Membrane-associated protein VP24 | Q05322 | Blocks IFN- Alpha /beta and IFN-gamma signaling. |

| L | RNA-directed RNA polymerase L | Q05318 | RNA replicase. |

Entry

[edit]

There are two candidates for host cell entry proteins. The first is a cholesterol transporter protein, the host-encoded Niemann–Pick C1 (NPC1), which appears to be essential for entry of Ebola virions into the host cell and for its ultimate replication.[28][29]In one study, mice with one copy of the NPC1 generemovedshowed an 80 percent survival rate fifteen days after exposure to mouse-adapted Ebola virus, while only 10 percent of unmodified mice survived this long.[28]In another study,small moleculeswere shown to inhibit Ebola virus infection by preventingviral envelopeglycoprotein (GP) from binding to NPC1.[29][30]Hence, NPC1 was shown to be critical to entry of thisfilovirus,because it mediates infection by binding directly to viral GP.[29]

When cells fromNiemann–Pick Type Cindividuals lacking this transporter were exposed to Ebola virus in the laboratory, the cells survived and appeared impervious to the virus, further indicating that Ebola relies on NPC1 to enter cells;[28]mutations in the NPC1 gene in humans were conjectured as a possible mode to make some individuals resistant to this deadly viral disease. The same studies described similar results regarding NPC1's role in virus entry forMarburg virus,a relatedfilovirus.[28]A further study has also presented evidence that NPC1 is the critical receptor mediating Ebola infection via its direct binding to the viral GP, and that it is the second "lysosomal" domain of NPC1 that mediates this binding.[31]

The second candidate is TIM-1 (a.k.a.HAVCR1).[32]TIM-1 was shown to bind to the receptor binding domain of the EBOV glycoprotein, to increase the receptivity ofVero cells.Silencing its effect with siRNA prevented infection ofVero cells.TIM1 is expressed in tissues known to be seriously impacted by EBOV lysis (trachea, cornea, and conjunctiva). A monoclonal antibody against the IgV domain of TIM-1, ARD5, blocked EBOV binding and infection. Together, these studies suggest NPC1 and TIM-1 may be potential therapeutic targets for an Ebola anti-viral drug and as a basis for a rapid field diagnostic assay.[citation needed]

Replication

[edit]

Being acellular, viruses such as Ebola do not replicate through any type of cell division; rather, they use a combination of host- and virally encoded enzymes, alongside host cell structures, to produce multiple copies of themselves. These then self-assemble into viralmacromolecular structuresin the host cell.[33]The virus completes a set of steps when infecting each individual cell. The virus begins its attack by attaching to host receptors through the glycoprotein (GP) surfacepeplomerand isendocytosedintomacropinosomesin the host cell.[34]To penetrate the cell, the viral membrane fuses withvesiclemembrane, and thenucleocapsidis released into thecytoplasm.Encapsidated, negative-sense genomic ssRNA is used as a template for the synthesis (3'–5') of polyadenylated, monocistronic mRNAs and, using the host cell's ribosomes, tRNA molecules, etc., the mRNA is translated into individual viral proteins.[35][36][37]

These viral proteins are processed: a glycoprotein precursor (GP0) is cleaved to GP1 and GP2, which are then heavily glycosylated using cellular enzymes and substrates. These two molecules assemble, first into heterodimers, and then into trimers to give the surface peplomers. Secreted glycoprotein (sGP) precursor is cleaved to sGP and delta peptide, both of which are released from the cell. As viral protein levels rise, a switch occurs from translation to replication. Using the negative-sense genomic RNA as a template, a complementary +ssRNA is synthesized; this is then used as a template for the synthesis of new genomic (-)ssRNA, which is rapidly encapsidated. The newly formed nucleocapsids and envelope proteins associate at the host cell's plasma membrane;buddingoccurs, destroying the cell.[citation needed]

Ecology

[edit]Ebola virus is azoonoticpathogen. Intermediary hosts have been reported to be "various species of fruit bats... throughout central and sub-Saharan Africa". Evidence of infection in bats has been detected through molecular and serologic means. However, ebolaviruses have not been isolated in bats.[8][38]End hosts are humans and great apes, infected through bat contact or through other end hosts. Pigs in the Philippines have been reported to be infected withReston virus,so other interim or amplifying hosts may exist.[38]Ebola virus outbreaks tend to occur when temperatures are lower and humidity is higher than usual for Africa.[39]Even after a person recovers from the acute phase of the disease, Ebola virus survives for months in certain organs such as the eyes and testes.[40]

Ebola virus disease

[edit]Zaire ebolavirus is one of the four ebolaviruses known to cause disease in humans. It has the highestcase-fatality rateof these ebolaviruses, averaging 83 percent since the first outbreaks in 1976, although a fatality rate of up to 90 percent was recorded in one outbreak in the Republic of the Congo between December 2002 and April 2003. There have also been more outbreaks of Zaire ebolavirus than of any other ebolavirus. The first outbreak occurred on 26 August 1976 inYambuku.[41]The first recorded case was Mabalo Lokela, a 44‑year-old schoolteacher. The symptoms resembledmalaria,and subsequent patients receivedquinine.Transmission has been attributed to reuse of unsterilized needles and close personal contact, body fluids and places where the person has touched. During the 1976 Ebola outbreak inZaire,Ngoy Musholatravelled fromBumbatoYambuku,where he recorded the first clinical description of the disease in his daily log:

The illness is characterized with a high temperature of about 39°C,hematemesis,diarrhea with blood, retrosternal abdominal pain, prostration with "heavy" articulations, and rapid evolution death after a mean of three days.[42]

Since the first recorded clinical description of the disease during 1976 in Zaire, the recent Ebola outbreak that started in March 2014, in addition, reached epidemic proportions and has killed more than 8000 people as of January 2015. This outbreak was centered in West Africa, an area that had not previously been affected by the disease. The toll was particularly grave in three countries: Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone. A few cases were also reported in countries outside of West Africa, all related to international travelers who were exposed in the most affected regions and later showed symptoms of Ebola fever after reaching their destinations.[43]

The severity of the disease in humans varies widely, from rapid fatality to mild illness or even asymptomatic response.[44]Studies of outbreaks in the late twentieth century failed to find a correlation between the disease severity and the genetic nature of the virus. Hence the variability in the severity of illness was suspected to correlate with genetic differences in the victims. This has been difficult to study in animal models that respond to the virus with hemorrhagic fever in a similar manner as humans, because typical mouse models do not so respond, and the required large numbers of appropriate test subjects are not easily available. In late October 2014, a publication reported a study of the response to a mouse-adapted strain of Zaire ebolavirus presented by a genetically diverse population of mice that was bred to have a range of responses to the virus that includes fatality from hemorrhagic fever.[45]

Vaccine

[edit]In December 2016, a study found theVSV-EBOVvaccine to be 70–100% effective against the Zaire ebola virus (not theSudan ebolavirus), making it the first vaccine against the disease.[46][47]VSV-EBOV was approved by the U.S.Food and Drug Administrationin December 2019.[48]

History and nomenclature

[edit]

Ebola virus was first identified as a possible new "strain" ofMarburg virusin 1976.[5][6][49]TheInternational Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses(ICTV) identifies Ebola virus asspeciesZaire ebolavirus,which is part of thegenusEbolavirus,familyFiloviridae,orderMononegavirales.The name "Ebola virus" is derived from theEbola River—a river that was at first thought to be in close proximity to the area inDemocratic Republic of Congo,previously calledZaire,where the1976 Zaire Ebola virus outbreakoccurred—and thetaxonomicsuffixvirus.[1][5][6][50]

In 1998, the virus name was changed to "Zaire Ebola virus"[51][52]and in 2002 to speciesZaire ebolavirus.[53][54]However, most scientific articles continued to refer to "Ebola virus" or used the terms "Ebola virus" and "Zaire ebolavirus"in parallel. Consequently, in 2010, a group of researchers recommended that the name" Ebola virus "be adopted for a subclassification within the speciesZaire ebolavirus,with the corresponding abbreviation EBOV.[1]Previous abbreviations for the virus were EBOV-Z (for "Ebola virus Zaire" ) and ZEBOV (for "Zaire Ebola virus" or "Zaire ebolavirus"). In 2011, the ICTV explicitly rejected a proposal (2010.010bV) to recognize this name, as ICTV does not designate names for subtypes, variants, strains, or other subspecies level groupings.[55]At present, ICTV does not officially recognize "Ebola virus" as a taxonomic rank, but rather continues to use and recommend only the species designationZaire ebolavirus.[56]TheprototypeEbola virus, variant Mayinga (EBOV/May), was named for Mayinga N'Seka, a nurse who died during the 1976 Zaire outbreak.[1][57][58]

The nameZaire ebolavirusis derived fromZaireand thetaxonomicsuffixebolavirus(which denotes an ebolavirus species and refers to theEbola River).[1]According to the rules for taxon naming established by theInternational Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses(ICTV), the nameZaire ebolavirusis always to becapitalized,italicized,and to be preceded by the word "species". The names of its members (Zaire ebolaviruses) are to be capitalized, are not italicized, and used withoutarticles.[1]

Virus inclusion criteria

[edit]A virus of the genusEbolavirusis a member of the speciesZaire ebolavirusif:[1]

- it is endemic in theDemocratic Republic of the Congo,Gabon,or theRepublic of the Congo

- it has a genome with two or threegene overlaps(VP35/VP40,GP/VP30,VP24/L)

- it has agenomic sequencethat differs from thetype virusEBOV/May by less than 30%

Evolution

[edit]Zaire ebolavirusdiverged from its ancestors between 1960 and 1976.[59]The genetic diversity ofEbolavirusremained constant before 1900.[59][60]Then, around the 1960s, most likely due to climate change or human activities, the genetic diversity of the virus dropped rapidly and most lineages became extinct.[60]As the number of susceptible hosts declines, so does the effective population size and its genetic diversity. This genetic bottleneck effect has implications for the species' ability to causeEbola virus diseasein human hosts.[citation needed]

Arecombinationevent betweenZaire ebolaviruslineages likely took place between 1996 and 2001 in wild apes giving rise to recombinant progeny viruses.[61]These recombinant viruses appear to have been responsible for a series of outbreaks among humans in Central Africa in 2001–2003.[61]

Zaire ebolavirus– Makona variant caused the 2014 West Africa outbreak.[62]The outbreak was characterized by the longest instance of human-to-human transmission of the viral species.[62]Pressures to adapt to the human host were seen at this time, however, no phenotypic changes in the virus (such as increased transmission, increased immune evasion by the virus) were seen.[citation needed]

In literature

[edit]- Alex Kava's 2008 crime novel,Exposed,focuses on the virus as a serial killer's weapon of choice.[63]

- William Close's 1995Ebola: A Documentary Novel of Its First Explosionand 2002Ebola: Through the Eyes of the Peoplefocused on individuals' reactions to the 1976 Ebola outbreak in Zaire.[64][65][66][67]

- The Hot Zone: A Terrifying True Story:A 1994 best-selling book by Richard Preston about Ebola virus and related viruses, including an account of the outbreak of an Ebolavirus in primates housed in a quarantine facility in Reston, Virginia, USA[68]

- Tom Clancy's 1996 novel,Executive Orders,involves aMiddle Easternterrorist attack on the United States using an airborne form of a deadly Ebola virus named "Ebola Mayinga".[69][70]

References

[edit]- ^abcdefghiKuhn JH, Becker S, Ebihara H, Geisbert TW, Johnson KM, Kawaoka Y, Lipkin WI, Negredo AI, et al. (2010)."Proposal for a revised taxonomy of the family Filoviridae: Classification, names of taxa and viruses, and virus abbreviations".Archives of Virology.155(12): 2083–2103.doi:10.1007/s00705-010-0814-x.PMC3074192.PMID21046175.

- ^Na, Woonsung; Park, Nanuri; Yeom, Minju; Song, Daesub (4 December 2016)."Ebola outbreak in Western Africa 2014: what is going on with Ebola virus?".Clinical and Experimental Vaccine Research.4(1): 17–22.doi:10.7774/cevr.2015.4.1.17.ISSN2287-3651.PMC4313106.PMID25648530.

- ^Ebola virus disease(Report). World Health Organization.Retrieved6 June2019.

- ^"Ebola virus disease outbreak".World Health Organization.Archivedfrom the original on 23 March 2021.Retrieved4 December2016.

- ^abcPattyn S, Jacob W, van der Groen G, Piot P, Courteille G (1977). "Isolation of Marburg-like virus from a case of haemorrhagic fever in Zaire".Lancet.309(8011): 573–574.doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(77)92002-5.PMID65663.S2CID33060636.

- ^abcBowen ETW, Lloyd G, Harris WJ, Platt GS, Baskerville A, Vella EE (1977). "Viral haemorrhagic fever in southern Sudan and northern Zaire. Preliminary studies on the aetiological agent".Lancet.309(8011): 571–573.doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(77)92001-3.PMID65662.S2CID3092094.

- ^WHO."Ebola virus disease".Archivedfrom the original on 14 December 2014.Retrieved5 October2020.

- ^abQuammen, David(30 December 2014)."Insect-Eating Bat May Be Origin of Ebola Outbreak, New Study Suggests".news.nationalgeographic.Washington, DC:National Geographic Society.Archived fromthe originalon 31 December 2014.Retrieved30 December2014.

- ^Angier, Natalie (27 October 2014)."Killers in a Cell but on the Loose – Ebola and the Vast Viral Universe".New York Times.Archivedfrom the original on 12 November 2020.Retrieved27 October2014.

- ^Nanbo, Asuka; Watanabe, Shinji; Halfmann, Peter; Kawaoka, Yoshihiro (4 February 2013)."The spatio-temporal distribution dynamics of Ebola virus proteins and RNA in infected cells".Scientific Reports.3:1206.Bibcode:2013NatSR...3E1206N.doi:10.1038/srep01206.PMC3563031.PMID23383374.

- ^"Ebola virus disease Fact sheet N°103".World Health Organization.March 2014.Archivedfrom the original on 14 December 2014.Retrieved12 April2014.

- ^Fauquet CM, Mayo MA, Maniloff J, Desselberger U, Ball LA, eds. (2005).Virus Taxonomy – Eighth Report of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses.Oxford: Elsevier/Academic Press. p. 648.ISBN978-0080575483.Archivedfrom the original on 14 January 2023.Retrieved7 February2016.

- ^Klenk, H.-D.; Feldmann, H., eds. (2004).Ebola and Marburg Viruses – Molecular and Cellular Biology.Wymondham, Norfolk, UK: Horizon Bioscience. p. 28.ISBN978-0-9545232-3-7.

- ^Feldmann, H. K. (1993). "Molecular biology and evolution of filoviruses".Unconventional Agents and Unclassified Viruses.Archives of Virology. Vol. 7. pp. 81–100.doi:10.1007/978-3-7091-9300-6_8.ISBN978-3211824801.ISSN0939-1983.PMID8219816.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^Lee, Jeffrey E; Saphire, Erica Ollmann (2009)."Ebolavirus glycoprotein structure and mechanism of entry".Future Virology.4(6): 621–635.doi:10.2217/fvl.09.56.ISSN1746-0794.PMC2829775.PMID20198110.

- ^Falasca L, Agrati C, Petrosillo N, Di Caro A, Capobianchi MR, Ippolito G, Piacentini M (4 December 2016)."Molecular mechanisms of Ebola virus pathogenesis: focus on cell death".Cell Death and Differentiation.22(8): 1250–1259.doi:10.1038/cdd.2015.67.ISSN1350-9047.PMC4495366.PMID26024394.

- ^Swetha, Rayapadi G.; Ramaiah, Sudha; Anbarasu, Anand; Sekar, Kanagaraj (2016)."Ebolavirus Database: Gene and Protein Information Resource for Ebolaviruses".Advances in Bioinformatics.2016:1673284.doi:10.1155/2016/1673284.ISSN1687-8027.PMC4848411.PMID27190508.

- ^abcKlenk, H.-D.; Feldmann, H., eds. (2004).Ebola and Marburg Viruses: Molecular and Cellular Biology.Horizon Bioscience.ISBN978-1904933496.[page needed]

- ^Hillman, H. (1991).The Case for New Paradigms in Cell Biology and in Neurobiology.Edwin Mellen Press.

- ^Zaire ebolavirus isolate H.sapiens-wt/GIN/2014/Makona-Kissidougou-C15, complete genomeArchived24 January 2018 at theWayback Machine,GenBank

- ^Taylor D, Leach R, Bruenn J (2010)."Filoviruses are ancient and integrated into mammalian genomes".BMC Evolutionary Biology.10(1): 193.Bibcode:2010BMCEE..10..193T.doi:10.1186/1471-2148-10-193.PMC2906475.PMID20569424.

- ^Belyi, V. A.; Levine, A. J.; Skalka, A. M. (2010). Buchmeier, Michael J. (ed.)."Unexpected Inheritance: Multiple Integrations of Ancient Bornavirus and Ebolavirus/Marburgvirus Sequences in Vertebrate Genomes".PLOS Pathogens.6(7): e1001030.doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1001030.PMC2912400.PMID20686665.

- ^Taylor DJ, Ballinger MJ, Zhan JJ, Hanzly LE, Bruenn JA (2014)."Evidence that ebolaviruses and cuevaviruses have been diverging from marburgviruses since the Miocene".PeerJ.2:e556.doi:10.7717/peerj.556.PMC4157239.PMID25237605.

- ^abRichard Preston (27 October 2014)."The Ebola Wars".The New Yorker.New York:Condé Nast.Archivedfrom the original on 25 January 2021.Retrieved20 October2014.

- ^abGire, Stephen K.; et al. (2014)."Genomic surveillance elucidates Ebola virus origin and transmission during the 2014 outbreak".Science.345(6202): 1369–1372.Bibcode:2014Sci...345.1369G.doi:10.1126/science.1259657.PMC4431643.PMID25214632.

- ^Check Hayden, Erika (5 May 2015)."Pint-sized DNA sequencer impresses first users".Nature.521(7550): 15–16.Bibcode:2015Natur.521...15C.doi:10.1038/521015a.ISSN0028-0836.PMID25951262.

- ^Jenkins GM, Rambaut A, Pybus OG, Holmes EC (2002). "Rates of molecular evolution in RNA viruses: A quantitative phylogenetic analysis".Journal of Molecular Evolution.54(2): 156–165.Bibcode:2002JMolE..54..156J.doi:10.1007/s00239-001-0064-3.PMID11821909.S2CID20759532.

- ^abcdCarette JE, Raaben M, Wong AC, Herbert AS, Obernosterer G, Mulherkar N, Kuehne AI, Kranzusch PJ, Griffin AM, Ruthel G, Dal Cin P, Dye JM, Whelan SP, Chandran K, Brummelkamp TR (September 2011)."Ebola virus entry requires the cholesterol transporter Niemann-Pick C1".Nature.477(7364): 340–343.Bibcode:2011Natur.477..340C.doi:10.1038/nature10348.PMC3175325.PMID21866103.

- Amanda Schaffer (16 January 2012)."Key Protein May Give Ebola Virus Its Opening".The New York Times.Archivedfrom the original on 20 February 2022.Retrieved26 February2017.

- ^abcCôté M, Misasi J, Ren T, Bruchez A, Lee K, Filone CM, Hensley L, Li Q, Ory D, Chandran K, Cunningham J (September 2011)."Small molecule inhibitors reveal Niemann-Pick C1 is essential for Ebola virus infection".Nature.477(7364): 344–348.Bibcode:2011Natur.477..344C.doi:10.1038/nature10380.PMC3230319.PMID21866101.

- Amanda Schaffer (16 January 2012)."Key Protein May Give Ebola Virus Its Opening".The New York Times.Archivedfrom the original on 20 February 2022.Retrieved26 February2017.

- ^Flemming A (October 2011)."Achilles heel of Ebola viral entry".Nat Rev Drug Discov.10(10): 731.doi:10.1038/nrd3568.PMID21959282.S2CID26888076.

- ^Miller EH, Obernosterer G, Raaben M, Herbert AS, Deffieu MS, Krishnan A, Ndungo E, Sandesara RG, Carette JE, Kuehne AI, Ruthel G, Pfeffer SR, Dye JM, Whelan SP, Brummelkamp TR, Chandran K (March 2012)."Ebola virus entry requires the host-programmed recognition of an intracellular receptor".EMBO Journal.31(8): 1947–1960.doi:10.1038/emboj.2012.53.PMC3343336.PMID22395071.

- ^Kondratowicz AS, Lennemann NJ, Sinn PL, et al. (May 2011)."T-cell immunoglobulin and mucin domain 1 (TIM-1) is a receptor for Zaire Ebolavirus and Lake Victoria Marburgvirus".Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America.108(20): 8426–8431.Bibcode:2011PNAS..108.8426K.doi:10.1073/pnas.1019030108.PMC3100998.PMID21536871.

- ^Biomarker Database.Ebola virus.Korea National Institute of Health. Archived fromthe originalon 22 April 2008.Retrieved31 May2009.

- ^Saeed MF, Kolokoltsov AA, Albrecht T, Davey RA (2010). Basler CF (ed.)."Cellular Entry of Ebola Virus Involves Uptake by a Macropinocytosis-Like Mechanism and Subsequent Trafficking through Early and Late Endosomes".PLOS Pathogens.6(9): e1001110.doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1001110.PMC2940741.PMID20862315.

- ^Mühlberger, Elke (4 December 2016)."Filovirus replication and transcription".Future Virology.2(2): 205–215.doi:10.2217/17460794.2.2.205.ISSN1746-0794.PMC3787895.PMID24093048.

- ^Feldmann, H.; Klenk, H.-D. (1996).Filoviruses.University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston.ISBN978-0963117212.Archivedfrom the original on 9 September 2018.Retrieved4 December2016.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^Lai, Kang Yiu; Ng, Wing Yiu George; Cheng, Fan Fanny (28 November 2014)."Human Ebola virus infection in West Africa: a review of available therapeutic agents that target different steps of the life cycle of Ebola virus".Infectious Diseases of Poverty.3:43.doi:10.1186/2049-9957-3-43.ISSN2049-9957.PMC4334593.PMID25699183.

- ^abFeldmann H (May 2014)."Ebola – A Growing Threat?".N. Engl. J. Med.371(15): 1375–1378.doi:10.1056/NEJMp1405314.PMID24805988.S2CID4657264.

- ^Ng, S.; Cowling, B. (2014)."Association between temperature, humidity and ebolavirus disease outbreaks in Africa, 1976 to 2014".Eurosurveillance.19(35): 20892.doi:10.2807/1560-7917.ES2014.19.35.20892.PMID25210981.

- ^"Clinical care for survivors of Ebola virus disease"(PDF).World Health Organization. 2016.Archived(PDF)from the original on 31 August 2016.Retrieved4 December2016.

- ^Isaacson M, Sureau P, Courteille G, Pattyn, SR."Clinical Aspects of Ebola Virus Disease at the Ngaliema Hospital, Kinshasa, Zaire, 1976".European Network for Diagnostics of "Imported" Viral Diseases (ENIVD). Archived fromthe originalon 4 August 2014.Retrieved24 June2014.

- ^Bardi, Jason Socrates."Death Called a River".The Scripps Research Institute.Archivedfrom the original on 2 August 2014.Retrieved9 October2014.

- ^name: S. Reardan.; N Engl. J Med. (2014) "The first nine months of the epidemic and projection, Ebola virus disease in west Africa". archive of Ebola Response Team. 511(75.11):520

- ^Gina Kolata (30 October 2014)."Genes Influence How Mice React to Ebola, Study Says in 'Significant Advance'".New York Times.Archivedfrom the original on 9 March 2021.Retrieved30 October2014.

- ^Rasmussen, Angela L.; et al. (30 October 2014)."Host genetic diversity enables Ebola hemorrhagic fever pathogenesis and resistance".Science.346(6212): 987–991.Bibcode:2014Sci...346..987R.doi:10.1126/science.1259595.PMC4241145.PMID25359852.

- ^Henao-Restrepo, Ana Maria; et al. (22 December 2016)."Efficacy and effectiveness of an rVSV-vectored vaccine in preventing Ebola virus disease: final results from the Guinea ring vaccination, open-label, cluster-randomised trial (Ebola Ça Suffit!)".The Lancet.389(10068): 505–518.doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)32621-6.PMC5364328.PMID28017403.

- ^Berlinger, Joshua (22 December 2016)."Ebola vaccine gives 100% protection, study finds".CNN.Archivedfrom the original on 27 December 2016.Retrieved27 December2016.

- ^"First FDA-approved vaccine for the prevention of Ebola virus disease, marking a critical milestone in public health preparedness and response".U.S.Food and Drug Administration(FDA).19 December 2019.Archivedfrom the original on 20 December 2019.Retrieved19 December2019.

- ^Brown, Rob (18 July 2014)."The virus detective who discovered Ebola".BBC News.Archivedfrom the original on 26 October 2021.Retrieved21 June2018.

- ^Johnson KM, Webb PA, Lange JV, Murphy FA (1977). "Isolation and partial characterisation of a new virus causing haemorrhagic fever in Zambia".Lancet.309(8011): 569–571.doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(77)92000-1.PMID65661.S2CID19368457.

- ^Netesov SV, Feldmann H, Jahrling PB, Klenk HD, Sanchez A (2000). "Family Filoviridae". In van Regenmortel MHV, Fauquet CM, Bishop DHL, Carstens EB, Estes MK, Lemon SM, Maniloff J, Mayo MA, McGeoch DJ, Pringle CR, Wickner RB (eds.).Virus Taxonomy – Seventh Report of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses.San Diego: Academic Press. pp. 539–548.ISBN978-0123702005.

- ^Pringle, C. R. (1998). "Virus taxonomy – San Diego 1998".Archives of Virology.143(7): 1449–1459.doi:10.1007/s007050050389.PMID9742051.S2CID13229117.

- ^Feldmann H, Geisbert TW, Jahrling PB, Klenk HD, Netesov SV, Peters CJ, Sanchez A, Swanepoel R, Volchkov VE (2005). "Family Filoviridae". In Fauquet CM, Mayo MA, Maniloff J, Desselberger U, Ball LA (eds.).Virus Taxonomy – Eighth Report of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses.San Diego: Elsevier/Academic Press. pp. 645–653.ISBN978-0123702005.

- ^Mayo, M. A. (2002)."ICTV at the Paris ICV: results of the plenary session and the binomial ballot".Archives of Virology.147(11): 2254–2260.doi:10.1007/s007050200052.S2CID43887711.

- ^"Replace the species name Lake Victoria marburgvirus with Marburg marburgvirus in the genus Marburgvirus".Archived fromthe originalon 5 March 2016.Retrieved31 October2014.

- ^International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses."Virus Taxonomy: 2013 Release".Archivedfrom the original on 10 July 2015.Retrieved31 October2014.

- ^Wahl-Jensen V, Kurz SK, Hazelton PR, Schnittler HJ, Stroher U, Burton DR, Feldmann H (2005)."Role of Ebola Virus Secreted Glycoproteins and Virus-Like Particles in Activation of Human Macrophages".Journal of Virology.79(4): 2413–2419.doi:10.1128/JVI.79.4.2413-2419.2005.PMC546544.PMID15681442.

- ^Kesel AJ, Huang Z, Murray MG, Prichard MN, Caboni L, Nevin DK, Fayne D, Lloyd DG, Detorio MA, Schinazi RF (2014)."Retinazone inhibits certain blood-borne human viruses including Ebola virus Zaire".Antiviral Chemistry & Chemotherapy.23(5): 197–215.doi:10.3851/IMP2568.PMC7714485.PMID23636868.S2CID34249020.

- ^abCarroll, S.A. (2012)."Molecular Evolution of Viruses of the Family Filoviridae Based on 97 Whole-Genome Sequences".Journal of Virology.87(5): 2608–2616.doi:10.1128/JVI.03118-12.PMC3571414.PMID23255795.

- ^abLi, Y.H. (2013)."Evolutionary history of Ebola virus".Epidemiology and Infection.142(6): 1138–1145.doi:10.1017/S0950268813002215.PMC9151191.PMID24040779.S2CID9873900.

- ^abWittmann TJ, Biek R, Hassanin A, Rouquet P, Reed P, Yaba P, Pourrut X, Real LA, Gonzalez JP, Leroy EM. "Isolates of Zaire ebolavirus from wild apes reveal genetic lineage and recombinants".Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A.2007 Oct 23;104(43):17123–17127. Epub 2007 Oct 17. "Erratum" in:Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A.2007 Dec 4;104(49):19656.PMID17942693

- ^ab"Outbreaks Chronology: Ebola Virus Disease".Ebola Hemorrhagic Feve.CDC. 2 August 2017.Archivedfrom the original on 17 May 2019.Retrieved11 November2017.

- ^Kava, Alex (October 2008).Fiction Book Review: 'Exposed' by Alex Kava, Author. Mira (332p).PublishersWeekly.ISBN978-0778325574.Archivedfrom the original on 7 November 2021.Retrieved7 November2021.

- ^Close, William T.(1995).Ebola: A Documentary Novel of Its First Explosion.New York:Ivy Books.ISBN978-0804114325.OCLC32753758.AtGoogle Books.

- ^Grove, Ryan (2 June 2006).More about the people than the virus.Archivedfrom the original on 21 October 2014.Retrieved17 September2014.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^Close, William T.(2002).Ebola: Through the Eyes of the People.Marbleton, Wyoming: Meadowlark Springs Productions.ISBN978-0970337115.OCLC49193962.Archivedfrom the original on 14 January 2023.Retrieved7 February2016.AtGoogle Books.

- ^Pink, Brenda (24 June 2008)."A fascinating perspective".Review of Close, William T., Ebola: Through the Eyes of the People.Archivedfrom the original on 21 October 2014.Retrieved17 September2014.

- ^Preston, Richard (1995).The Hot Zone.New York: Anchor.ISBN0385479565.OCLC32052009.

- ^Clancy, Tom(1996).Executive Orders.New York: Putnam.ISBN978-0399142185.OCLC34878804.

- ^Stone, Oliver(2 September 1996)."Who's That in the Oval Office?".Books News & Reviews.The New York Times Company.Archived fromthe originalon 10 April 2009.Retrieved10 September2014.

Further reading

[edit]- Pacheco, Daniela Alexandra de Meneses Rocha; Rodrigues, Acácio Agostinho Gonçalves; Silva, Carmen Maria Lisboa da (October 2016)."Ebola virus – from neglected threat to global emergency state".Revista da Associação Médica Brasileira.62(5): 458–467.doi:10.1590/1806-9282.62.05.458.PMID27656857.

External links

[edit]- Ebolavirus molecular biology

- Ebolavirus proteins (PDB-101)

- ICTV Files and Discussions – Discussion forum and file distribution for the International Committee on Taxonomy of VirusesArchived7 October 2011 at theWayback Machine

- Genomic data onEbolavirus isolates and other members of the familyFiloviridae

- ViralZone: Ebola-like viruses– Virological repository from theSwiss Institute of Bioinformatics

- Virus Pathogen Resource: Ebola Portal– Genomic and other research data about Ebola and other human pathogenic viruses

- The Ebola Virus3D model of the Ebola virus, prepared by Visual Science, Moscow.

- FILOVIR – scientific resources for research on filovirusesArchived30 July 2020 at theWayback Machine

- "'Zaire ebolavirus'".NCBI Taxonomy Browser.186538.

- "'Ebola virus sp.'".NCBI Taxonomy Browser.205488.