Galician phonology

This article is about thephonologyandphoneticsof theGalician language.

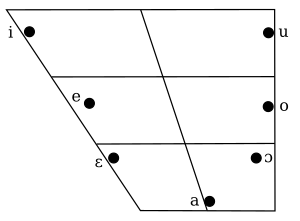

Vowels

[edit]

Galician has seven vowel phonemes, which are represented by five letters in writing. Similar vowels are found under stress instandard CatalanandItalian.It is likely that this 7-vowel system was even more widespread inthe early stages of Romance languages.

| Phoneme (IPA) | Grapheme | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| /a/ | a | nada |

| /e/ | e | tres |

| /ɛ/ | ferro | |

| /i/ | i | min |

| /o/ | o | bonito |

| /ɔ/ | home | |

| /u/ | u | rúa |

Some characteristics of the vocalic system:

- In Galician the vocalic system is reduced to five vowels in post-tonic syllables, and to just three in final unstressed position:[ɪ,ʊ,ɐ](which can instead be transcribed as[e̝,o̝,a̝]).[1]In some cases, vowels from the final unstressed set appear in other positions, as e.g. in the wordtermonuclear[ˌtɛɾmʊnukleˈaɾ],because the prefixtermo-is pronounced[ˈtɛɾmʊ].[2][3]

- Unstressed close-mid vowels and open-mid vowels (/e~ɛ/and/o~ɔ/) can occur in complementary distribution (e.g.ovella[oˈβeɟɐ]'sheep' /omitir[ɔmiˈtiɾ]'to omit' andpequeno[peˈkenʊ]'little, small' /emitir[ɛmiˈtiɾ]'to emit'), with a few minimal pairs likebotar[boˈtaɾ]'to throw' vs.botar[bɔˈtaɾ]'to jump'.[4]In pretonic syllables, close-/open-mid vowels are kept in derived words and compounds (e.g.c[ɔ]rd- >corda[ˈkɔɾðɐ]'string' →cordeiro[kɔɾˈðejɾʊ]'string-maker'—which contrasts withcordeiro[koɾˈðejɾʊ]'lamb').[4]

- The distribution of stressed close-mid vowels (/e/, /o/) and open-mid vowels (/ɛ/, /ɔ/) are as follows:[5]

- Vowels with graphic accents are usually open-mid, such asvén[bɛŋ],só[s̺ɔ],póla[ˈpɔlɐ],óso[ˈɔs̺ʊ],présa[ˈpɾɛs̺ɐ].

- Nouns ending in-elor-oland their plural forms have open-mid vowels, such aspapel[paˈpɛl] 'paper' orcaracol[kaɾaˈkɔl] 'snail'.

- Second-person singular and third-person present indicative forms of second conjugation verbs(-er)with the thematic vowel /e/ or /u/ have open-mid vowels, while all remaining verb forms maintain close-mid vowels:

- bebo[ˈbeβʊ],bebes[ˈbɛβɪs̺],bebe[ˈbɛβɪ],beben[ˈbɛβɪŋ]

- como[ˈkomʊ],comes[ˈkɔmɪs̺],come[ˈkɔmɪ],comen[ˈkɔmɪŋ]

- Second-person singular and third-person present indicative forms of third conjugation verbs(-ir)with the thematic vowel /e/ or /u/ have open-mid vowels, while all remaining verb forms maintain close vowels:

- sirvo[ˈs̺iɾβʊ],serves[ˈs̺ɛɾβɪs̺],serve[ˈs̺ɛɾβɪ],serven[ˈs̺ɛɾβɪŋ]

- fuxo[ˈfuʃʊ],foxes[ˈfɔʃɪs̺],foxe[ˈfɔʃɪ],foxen[ˈfɔʃɪŋ]

- Certain verb forms derived from irregular preterite forms have open-mid vowels:

- preterite indicative: coubeches [kowˈβɛt͡ʃɪs̺], coubemos [kowˈβɛmʊs̺], coubestes [kowˈβɛs̺tɪs̺], couberon [kowˈβɛɾʊŋ]

- pluperfect: eu/el coubera [kowˈβɛɾɐ], couberas [kowˈβɛɾɐs̺], couberan [kowˈβɛɾɐŋ]

- preterite subjunctive: eu/el coubese [kowˈβɛs̺ɪ], coubeses [kowˈβɛs̺ɪs̺], coubesen [kowˈβɛs̺ɪŋ]

- future subjunctive: eu/el couber [kowˈβɛɾ], couberes [kowˈβɛɾɪs̺], coubermos [kowˈβɛɾmʊs̺], couberdes [kowˈβɛɾðɪs̺], couberen [kowˈβɛɾɪŋ]

- The letter namese[ˈɛ],efe[ˈɛfɪ],ele[ˈɛlɪ],eme[ˈɛmɪ],ene[ˈɛnɪ],eñe[ˈɛɲɪ],erre[ˈɛrɪ],ese[ˈɛs̺ɪ],o[ˈɔ] have open-mid vowels, while the remaining letter names have close-mid vowels.

- Close-mid vowels:

- verb forms of first conjugation verbs with a thematic mid vowel followed by-i-or palatalx, ch, ll, ñ(deitar, axexar, pechar, tellar, empeñar, coxear)

- verb forms of first conjugation verbs ending in-earor-oar(voar)

- verbs forms derived from the irregular preterite form ofserandir(fomos, fora, fose, for)

- verbs forms derived from regular preterite forms(collemos, collera, collese, coller)

- infinitives of second conjugation verbs(coller, pór)

- the majority of words ending in-és(coruñés, vigués, montañés)

- the diphthongou(touro, tesouro)

- nouns ending in-edo, -ello, -eo, -eza, ón, -or, -oso(medo, cortello, feo, grandeza, corazón, matador, fermoso)

- Of the seven vocalic phonemes of the tonic and pretonic syllables, only/a/has a set of different renderings (allophones), forced by its context:[6]

- All dialectal forms of Galician but Ancarese, spoken in theAncaresvalley inLeón,have lost the phonemic quality of mediaevalnasal vowels.Nevertheless, any vowel is nasalized in contact with a nasal consonant.[8]

- The vocalic system of Galician language is heavily influenced bymetaphony.Regressive metaphony is produced either by a final/a/,which tend to open medium vowels, or by a final/o/,which can have the reverse effect. As a result, metaphony affects most notably words with gender opposition:sogro[ˈsoɣɾʊ]('father-in-law') vs.sogra[ˈsɔɣɾɐ]('mother-in-law').[9]On the other hand,vowel harmony,triggered by/i/or/u/,has had a large part in the evolution and dialectal diversification of the language.

- Diphthongs

Galician language possesses a large set of fallingdiphthongs:

| falling | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [aj] | caixa | 'box' | [aw] | autor | 'author' |

| [ɛj] | papeis | 'papers' | [ɛw] | deu | 'he/she gave' |

| [ej] | queixo | 'cheese' | [ew] | bateu | 'he/she hit' |

| [ɔj] | bocoi | 'barrel' | |||

| [oj] | loita | 'fight' | [ow] | pouco | 'little' |

There are also a certain number of rising diphthongs, but they are not characteristic of the language and tend to be pronounced as hiatus.[10]

Consonants

[edit]| Labial | Dental | Alveolar | Post- alveolar |

Palatal | Velar | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n | ɲ | ŋ | ||||||

| Plosive/Affricate | p | b | t | d | tʃ | ɟ | k | ɡ | ||

| Fricative | f | θ | s | ʃ | ||||||

| Approximant | w | l | j | |||||||

| Trill | r | |||||||||

| Flap | ɾ | |||||||||

| Phoneme(IPA) | Mainallophones[11][12] | Graphemes | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| /b/ | [b],[β̞] | b, v | bebo[ˈbeβ̞ʊ]'(I) drink',alba[ˈalβ̞ɐ]'sunrise',vaca[ˈbakɐ]'cow',cova[ˈkɔβ̞ɐ]'cave' |

| /θ/ | [θ](dialectal[s]) | z, c | macio[ˈmaθjʊ]'soft',cruz[ˈkɾuθ]'cross' |

| /tʃ/ | [tʃ] | ch | chamar[tʃaˈmaɾ]'to call',achar[aˈtʃaɾ]'to find' |

| /d/ | [d],[ð̞] | d | vida[ˈbið̞ɐ]'life',cadro[ˈkað̞ɾʊ]'frame' |

| /f/ | [f] | f | feltro[ˈfɛltɾʊ]'filter',freixo[ˈfɾejʃʊ]'ash-tree' |

| /ɡ/ | [ɡ],[ɣ](dialectal[ħ]) | g, gu | fungo[ˈfuŋɡʊ]'fungus',guerra[ˈɡɛrɐ]'war',o gato[ʊˈɣatʊ]'the cat' |

| /ɟ/ | [ɟ],[ʝ˕],[ɟʝ] | ll, i | mollado[moˈɟað̞ʊ]'wet' |

| /k/ | [k] | c, qu | casa[ˈkasɐ]'house',querer[keˈɾeɾ]'to want' |

| /l/ | [l] | l | lúa[ˈluɐ]'moon',algo[ˈalɣʊ]'something',mel[ˈmɛl]'honey' |

| /m/ | [m],[ŋ][13] | m | memoria[meˈmɔɾjɐ]'memory',campo[ˈkampʊ]'field',álbum[ˈalβuŋ] |

| /n/ | [n],[m],[ŋ][13] | n | niño[ˈniɲʊ]'nest',onte[ˈɔntɪ]'yesterday',conversar[kombeɾˈsaɾ]'to talk',irmán[iɾˈmaŋ]'brother' |

| /ɲ/ | [ɲ][13] | ñ | mañá[maˈɲa]'morning' |

| /ŋ/ | [ŋ][13] | nh | algunha[alˈɣuŋɐ]'some' |

| /p/ | [p] | p | carpa[ˈkaɾpɐ]'carp' |

| /ɾ/ | [ɾ] | r | hora[ˈɔɾɐ]'hour',coller[koˈʎeɾ]'to grab' |

| /r/ | [r] | r, rr | rato[ˈratʊ]'mouse',carro[ˈkarʊ]'cart' |

| /s/ | [s̺,z̺](dialectal[s̻,z̻])[14] | s | selo[ˈs̺elʊ]'seal, stamp',cousa[ˈkows̺ɐ]'thing',mesmo[ˈmɛz̺mʊ]'same' |

| /t/ | [t] | t | trato[ˈtɾatʊ]'deal' |

| /ʃ/ | [ʃ] | x[15] | xente[ˈʃentɪ]'people',muxica[muˈʃikɐ]'ash-fly' |

Voiced plosives (/ɡ/,/d/and/b/) arelenited (weakened)toapproximantsorfricativesin all instances, except after apauseor anasal consonant;e.g.un gato'a cat' is pronounced[uŋˈɡatʊ],whilsto gato'the cat' is pronounced[ʊˈɣatʊ].

During the modern period, Galician consonants have undergone significant sound changes that closely parallel theevolution of Spanish consonants,including the following changes that neutralized the opposition ofvoicedfricatives / voiceless fricatives:

- /z/>/s/;

- /dz/>/ts/>[s]in western dialects, or[θ]in eastern and central dialects;

- /ʒ/>/ʃ/;

For a comparison, seeDifferences between Spanish and Portuguese: Sibilants.Additionally, during the 17th and 18th centuries the western and central dialects of Galician developed a voiceless fricative pronunciation of/ɡ/(a phenomenon calledgheada). This may be glottal[h],pharyngeal[ħ],uvular[χ],or velar[x].[16]

The distribution of the two rhotics/r/and/ɾ/closely parallelsthat of Spanish.Between vowels, the two contrast (e.g.mirra[ˈmirɐ]'myrrh' vs.mira[ˈmiɾɐ]'look'), but they are otherwise in complementary distribution.[ɾ]appears in the onset, except in word-initial position (rato), after/l/,/n/,and/s/(honra,Israel), where[r]is used.

As in Spanish,/ɟ/derives from historical/ʎ/(yeísmo) and from syllable-initial/j/.In some dialects, it lenites to approximant[ʝ˕]in the same environments where/b,d,ɡ/lenite. It may also be realized as[ɟʝ]where it derives from/j/.The realization[ʎ]remains in select older speakers in isolated regions.[12]

References

[edit]- ^E.g. byRegueira (2010)

- ^Regueira (2010:13–14, 21)

- ^Freixeiro Mato (2006:112)

- ^abFreixeiro Mato (2006:94–98)

- ^"Pautas para diferenciar as vogais abertas das pechadas".Manuel Antón Mosteiro.Retrieved2019-02-19.

- ^Freixeiro Mato (2006:72–73)

- ^"Dicionario de pronuncia da lingua galega: á".Ilg.usc.es.Retrieved2012-06-30.

- ^Sampson (1999:207–214)

- ^Freixeiro Mato (2006:87)

- ^Freixeiro Mato (2006:123)

- ^Freixeiro Mato (2006:136–188)

- ^abMartínez-Gil (2022),pp. 900–902.

- ^abcdThe phonemes/m/,/n/,/ɲ/and/ŋ/coalesce in implosive position as the archiphoneme/N/,which, phonetically, is usually[ŋ].Cf.Freixeiro Mato (2006:175–176)

- ^Regueira (1996:82)

- ^xcan stand also for[ks]

- ^Regueira (1996:120)

Bibliography

[edit]- Freixeiro Mato, Xosé Ramón (2006),Gramática da lingua galega (I). Fonética e fonoloxía(in Galician), Vigo: A Nosa Terra,ISBN978-84-8341-060-8

- Martínez-Gil, Fernando (2022), "Galician", in Gabriel, Christoph; Gess, Randall; Meisenburg, Trudel (eds.),Manual of Romance Phonetics and Phonology,Berlin: De Gruyter,ISBN978-3-11-054835-8

- Regueira, Xosé Luís (1996), "Galician",Journal of the International Phonetic Association,26(2): 119–122,doi:10.1017/s0025100300006162

- Regueira, Xosé Luís (2010),Dicionario de pronuncia da lingua galega(PDF),A Coruña: Real Academia Galega,ISBN978-84-87987-77-9

- Sampson, Rodney (1999),Nasal vowel evolution in Romance,Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press,ISBN978-0-19-823848-5