Derek Jarman

Derek Jarman | |

|---|---|

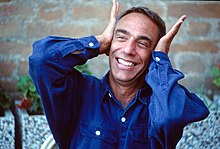

Jarman during the 1991 Venice Film Festival | |

| Born | 31 January 1942[1] |

| Died | 19 February 1994(aged 52) St Bartholomew's Hospital,London, England |

| Resting place | St Clement Churchyard,Old Romney,Kent |

| Education | Canford School,Dorset |

| Alma mater | King's College London Slade School of Fine Art(UCL) |

| Occupation(s) | Film director,gay rights activist,gardener,set designer |

| Years active | 1970–1994 |

| Notable work | Sebastiane(1976) Jubilee(1977) The Tempest(1979) Caravaggio(1986) The Last of England(1988) War Requiem(1989) Edward II(1991) Wittgenstein(1993) Blue(1993) |

| Style | New Queer Cinema[3] |

| Partner(s) | Philip Macdonald (1980–1988) Keith Collins (1987–1994; his death)[4] |

Michael Derek Elworthy Jarman[2](31 January 1942 – 19 February 1994) was an Englishartist,film maker,costume designer,stage designer,writer,poet,gardener,andgay rightsactivist.

Biography

[edit]

Jarman was born at the Royal Victoria Nursing Home inNorthwood,Middlesex,England,[2]the son of Elizabeth Evelyn (néePuttock)[5]and Lancelot Elworthy Jarman.[6][7]His father was aRoyal Air Forceofficer, born inNew Zealand.

After a prep school education atHordle House School,Jarman went on to board atCanford Schoolin Dorset and from 1960 studied English and art atKing's College London.This was followed by four years at theSlade School of Fine Art,University College London(UCL), starting in 1963. He had a studio atButler's Wharf,London, in the 1970s. Jarman was outspoken about homosexuality, his public fight forgay rights,and his personal struggle with AIDS.

On 22 December 1986, Jarman was diagnosed asHIV positiveand discussed his condition in public. His illness prompted him to move toProspect Cottage,Dungeness,in Kent, near thenuclear power station.In 1994, he died of an AIDS-related illness in London,[8]aged 52. He was anatheist.[9]He is buried in the graveyard atSt Clement's Church,Old Romney,Kent.

In his last years, Jarman was emotionally and practically supported by the companionship of Keith Collins, a young man he had met in 1987. While not lovers (Collins had his own partner), the friendship became essential for both of them. Jarman leftProspect Cottageto him.[10]

Ablue plaquecommemorating Jarman was unveiled at Butler's Wharf in London on 19 February 2019, the 25th anniversary of his death.[11]

Films

[edit]Jarman's first films were experimentalSuper 8mmshorts, a form he never entirely abandoned, and later developed further in his filmsImagining October(1984),The Angelic Conversation(1985),The Last of England(1987), andThe Garden(1990) as a parallel to his narrative work.The Gardenwas entered into the17th Moscow International Film Festival.[12]The Angelic ConversationfeaturedToby Mottand other members of theGrey Organisation,a radical artist collective.[13]

Jarman first became known as a stage designer. His break in the film industry came as production designer forKen Russell'sThe Devils(1971).[14]He made his mainstream narrative filmmaking debut withSebastiane(1976), about the martyrdom ofSaint Sebastian.This was one of the first British films to feature positive images of gaysexuality;[15]its dialogue was entirely inLatin.

He followed this withJubilee(shot 1977, released 1978), in which QueenElizabeth I of Englandis seen to be transported forward in time to a desolate and brutal wasteland ruled by her twentieth-century namesake.[16]Jubileehas been described as "Britain's only decentpunk film",[17]and featured punk groups and figures such asJayne CountyofWayne County & the Electric Chairs,Jordan,Toyah Willcox,Adam and the Antsand The Slits.

This was followed in 1979 by an adaptation of Shakespeare'sThe Tempest.[18]

During the 1980s, Jarman was a leading campaigner againstClause 28,which sought to ban the "promotion" of homosexuality in schools. He also worked to raise awareness of AIDS. His artistic practice in the early 1980s reflected these commitments, especially inThe Angelic Conversation(1985), a film in which the imagery is accompanied byJudi Dench's voice recitingShakespeare's sonnets.

Jarman spent seven years making experimental Super 8mm films and attempting to raise money forCaravaggio(he later claimed to have rewritten the script seventeen times during this period). Released in 1986,Caravaggio[19]attracted a comparatively wide audience; it is still, barring the cult hitJubilee,probably Jarman's most widely known work. This is partly due to the involvement, for the first time with a Jarman film, of the British television companyChannel 4in funding and distribution. Funded by theBritish Film Instituteand produced by film theoristColin MacCabe,Caravaggiobecame Jarman's most famous film to date, and marked the beginning of a new phase in his filmmaking career: from then onwards, all his films would be partly funded by television companies, often receiving their most prominent exhibition in TV screenings.Caravaggioalso saw Jarman work with actressTilda Swintonfor the first time. Overt depictions of homosexual love, narrative ambiguity, and the live representations ofCaravaggio's most famous paintings are all prominent features in the film.

The conclusion ofCaravaggioalso marked the beginning of a temporary abandonment of traditional narrative in Jarman's films. Frustrated by the formality of35mm filmproduction, and by the dependence on institutions and the resultant prolonged inactivity associated with it (which had already cost him seven years withCaravaggio,as well as derailing several long-term projects), Jarman returned to and expanded the super 8mm-based form he had previously worked in onImagining OctoberandThe Angelic Conversation.Caravaggiowas entered into the36th Berlin International Film Festival,where it won theSilver Bearfor an outstanding single achievement.[20]

The first film to result from this new semi-narrative phase,The Last of Englandtold the death of a country, ravaged by its own internal decay and the economic restructuring ofThatcher's government."Wrenchingly beautiful… the film is one of the few commanding works of personal cinema in the late 80's – a call to open our eyes to a world violated by greed and repression, to see what irrevocable damage has been wrought on city, countryside and soul, how our skies, our bodies, have turned poisonous", wrote aVillage Voicecritic.

In 1989, Jarman's filmWar Requiemproduced byDon BoydbroughtLaurence Olivierout of retirement for what would be Olivier's last screen performance. The film usesBenjamin Britten's eponymousanti-war requiemas its soundtrack and juxtaposes violent footage of war with the mass for the dead and the passionate humanist poetry ofWilfred Owen.

During the making of his filmThe Garden,Jarman became seriously ill. Although he recovered sufficiently to complete the work, he never attempted anything on a comparable scale afterwards, returning to a more pared-down form for his concluding narrative films,Edward II(perhaps his most politically outspoken work, informed by his gay activism) and theBrechtianWittgenstein,a delicate tragicomedy based on the life of the philosopherLudwig Wittgenstein.Jarman made a side income by directingmusic videosfor various artists, includingMarianne Faithfull,[21]The Smithsand thePet Shop Boys.[22]

By the time of his 1993 filmBlue,[23]Jarman was losing his sight and dying of AIDS-related complications.Blueconsists of a single shot of saturated blue colour filling the screen, as background to a soundtrack composed bySimon Fisher Turner,and featuring original music byCoiland other artists, in which Jarman describes his life and vision. When it was shown on British television,Channel 4carried the image whilst the soundtrack was broadcast simultaneously onBBC Radio 3.[24]Bluewas unveiled at the1993 Venice Biennalewith Jarman in attendance and subsequently entered the collections of the Walker Art Institute;[25]Centre Georges Pompidou,[26]MoMA[27]andTate.[23]His final work as a film-maker was the filmGlitterbug,[28]made for theArenaslot onBBC Two,and broadcast shortly after Jarman's death.

Other works

[edit]

Jarman's work broke new ground in creating and expanding the fledgling form of 'thepop video' in England (eg. using his father'sWWIIarchival footage(one of the first people to use a colorhome moviecamera which included the director as a toddler) on the early version ofWang Chung's "Dance Hall Days"), and ingay rightsactivism.[29]

Jarman also directed the 1989 tour by the UK duoPet Shop Boys.By pop concert standards this was a highly theatrical event with costume and specially shot films accompanying the individual songs. Jarman was the stage director ofSylvano Bussotti's operaL'Ispirazione,first staged in Florence in 1988.

Jarman is also remembered for his famous shingle cottage-garden atProspect Cottage,created in the latter years of his life, in the shadow ofDungeness nuclear power station.The cottage is built in vernacular style in timber, with tar-based weatherproofing, like others nearby. Raised wooden text on the side of the cottage is the first stanza and the last five lines of the last stanza ofJohn Donne's poem,The Sun Rising.The cottage garden was made by arrangingflotsamwashed up nearby, interspersed withendemicsalt-loving beach plants, both set against the bright shingle. The garden has been the subject of several books. At this time, Jarman also began painting again.[30]

In 2020 theGarden Museumin London held an exhibition called"Derek Jarman: my Garden's Boundaries are the Horizon"[31]parts of the garden andProspect Cottagewere recreated for the exhibition as well as artifacts from Jarman's estate.[32][33]

Jarman was the author of several books including hisautobiographyDancing Ledge(1984), which details his life until the age 40. He provides his own insight on the history of gay life in London (1960s-1980s), discusses his own acceptance of his homosexuality at age 16 and accounts of the financial and emotional hardships of a life devoted to filmmaking.[34]A collection of poetryA Finger in the Fishes Mouth,two volumes of diariesModern NatureandSmiling In Slow Motionand two treatises on his work in film and artThe Last of England(also published asKicking the Pricks) andChroma.

Other notable published works include film scripts (Up in the Air,Blue,War Requiem,Caravaggio,Queer Edward IIandWittgenstein: The Terry Eagleton Script/The Derek Jarman Film), a study of his garden at DungenessDerek Jarman's Garden,andAt Your Own Risk,a defiant celebration of gay sexuality.

Musical tributes

[edit]After his death, the bandChumbawambareleased "Song for Derek Jarman" in his honour.Andi Sexgangreleased the CDLast of Englandas a Jarman tribute. The ambient experimental albumThe Garden Is Full of MetalbyRobin Rimbaudincluded Jarman speech samples.[35]

Manic Street Preachers' bassistNicky Wirerecorded a track titled "Derek Jarman's Garden" as ab-sideto his single "Break My Heart Slowly"(2006). On his albumIn the Mist,released in 2011, ambient composerHarold Buddfeatures a song titled "The Art of Mirrors (after Derek Jarman)".[36]

Coil,which in 1985 contributed a soundtrack for Jarman'sThe Angelic Conversation[37]released the 7 "single" Themes for Derek Jarman's Blue "[38]in 1993. In 2004, Coil'sPeter Christophersonperformed his score for the Jarman shortThe Art of Mirrorsas a tribute to Jarman live at L'étrange Festival in Paris. In 2015, record label Black Mass Rising released a recording of the performance.[39]In 2018, composerGregory Spearscreated a work for chorus and string quartet, titled "The Tower and the Garden", commissioned by conductors Donald Nally, Mark Shapiro, Robert Geary and Carmen-Helena Téllez, setting a poem byKeith Garebianfrom his collection "Blue: The Derek Jarman Poems" (2008).

The French musician and composer Romain Frequency released his first albumResearch on a nameless colour[40]in 2020 as a tribute to Jarman's final collection of Essays “Chroma” released in 1994, the year he died and written while struggling with illness (facing the irony of an artist going blind). The songs are devoted to an unexisting colour and their attendant emotion as a transposition of a certain contemplative state into sound. The album received a positive response from the press.[41]

Filmography

[edit]Feature films

[edit]- Sebastiane(1976)

- Jubilee(1978)

- The Tempest(1979)

- The Angelic Conversation(1985)

- Caravaggio(1986)

- The Last of England(1987)

- War Requiem(1989)

- The Garden(1990)

- Edward II(1991)

- Wittgenstein(1993)

- Blue(1993)

Short films

[edit]- Studio Bankside(1971)

- Electric Fairy(1971)

- Garden of Luxor(akaBurning the Pyramids1972)

- Burning the Pyramids(1972)

- Miss Gaby(1972)

- A Journey to Avebury(1971)

- Andrew Logan Kisses the Glitterati(1972)

- At Low Tide(1972)

- Tarot(akathe Magician,1972)

- Art of Mirrors(1973)

- Sulphur(1973)

- Stolen Apples for Karen Blixen(1973)

- Ashden's Walk on Møn(1973)

- Miss World(1973)

- The Devils at the Elgin(akaReworking the Devils,1974)

- Fire Island(1974)

- Duggie Fields(1974)

- Ulla's Fete(akaUlla's Chandelier,1975)

- Picnic at Ray's(1975)

- Sebastiane Wrap(1975)

- The Making of Sebastiane(1975)

- Sea of Storms(1976)

- Sloane Square: A Room of One's Own(1976)

- Gerald's Film(1976)

- Art and the Pose(1976)

- Houston Texas(1976)

- Jordan's Dance(1977)

- Every Woman for Herself and All for Art(1977)

- The Pantheon(1978)

- In the Shadow of the Sun(1974) (in 1981Throbbing Gristlewas commissioned to providea new soundtrackfor this 54-minute film)

- T.G.: Psychic Rally in Heaven(1981)

- Jordan's Wedding(1981)

- Waiting for Waiting for Godot(1982)

- Pontormo and Punks at Santa Croce(1982)

- B2 Tape(1983)

- The Dream Machine(1983) (Consists of multiple short vignettes of previous works)

- Witches Song(1979)

- Broken English(1979)

- Ballad Of Lucy Jordan(1979)

- Pirate Tape(1983)

- T.G.: Psychic Rally In Heaven(1981).

- Imagining October(1984)

- Pirate Tape (William S. BurroughsFilm)(1987)

- Aria(1987)

- segment:Depuis le Jour

- L'Ispirazione(1988)

- Coil: Egyptian Basses(1993)

- The Clearing(1994)[42]

- Glitterbug(1994) (one-hour compilation film of various Super-8 shorts with music byBrian Eno)

- Will You Dance With Me? "(2014) (filmed in 1984 but released posthumously)[43]

Jarman's early Super-8 mm work has been included on some of the DVD releases of his films.

Music videos

[edit]- The Sex Pistols:The Sex Pistols Number One(1977)[44]

- Marianne Faithfull:"Broken English",[21]"Witches' Song", and "The Ballad of Lucy Jordan" (1979)[44]

- Throbbing Gristle:"TG Psychic Rally in Heaven" (1981)[45]

- The Lords of the New Church:"Dance With Me" (1983)[46]

- Carmel:"Willow Weep for Me" (1983)[46]

- Wang Chung:"Dance Hall Days"(first version) (1983)[47]

- Psychic TVJordi Valls: "Catalan" (1984)[44]

- Language: "Touch The Radio Dance" (1984)[48](shown at theMuseum of Modern Artin New York City)

- Wide Boy AwakeBilly Hyena (1984)

- Orange Juice:"What Presence?!" (1984)[44]

- Marc Almond:"Tenderness Is a Weakness" (1984)[49]

- Bryan Ferry:"Windswept" (1985)[50]

- The Smiths:

- The Queen Is Dead,a short film incorporating the Smiths songs "The Queen Is Dead",[22]"Panic",and"There Is a Light That Never Goes Out"(1986)[51]

- The "Panic" sequence fromThe Queen Is Deadwas edited to form the video for that single (1986)

- "Ask"(1986)[22][52]

- Easterhouse:"1969" and "Whistling in the Dark" (1986)[46]

- Matt Fretton: "Avatar" (unreleased) (1986)[44]

- The Mighty Lemon Drops"Out of Hand" (1987)[44]

- Bob Geldof:"I Cry Too" and "In The Pouring Rain" (1987)[44]

- Pet Shop Boys:"It's a Sin"(1987),[22]"Rent"(1987),[22]several concert projections (released asProjectionsin 1993),[44]and "Violence"(1995)[53]

- Suede:"The Next Life"(1993)[54]

- Patti Smith:"Memorial Tribute" (1993)[55]

Scenic design

[edit]- Jazz Calendarat Covent Garden.[56]

- Don Giovanniat the Coliseum[56]

- The Devils,directed byKen Russell[56]

- Savage Messiah,directed by Ken Russell[56]

- The Rake's Progress,directed by Ken Russell in Florence[56]

- 1991:Waiting for GodotbySamuel Beckettat theQueen's Theatrein theWest End[56]

Bibliography

[edit]- Dancing Ledge(1984)

- Kicking the Pricks(1987)

- Modern Nature: Journals, 1989-1990(1991)

- At Your Own Risk(1992)

- Chroma(1993)

- A Finger in the Fishes Mouth,poetry

- Derek Jarman's Garden(1995)

- Smiling in Slow Motion: Journals, 1991-1994(2000)

Film and television works prompted by Jarman's life and work

[edit]- The Last Paintings of Derek Jarman(Mark Jordan, Granada TV 1995). Broadcast byGranada TVand shown at the San Francisco Frameline Film Festival. Includes footage of Jarman producing his final works. Guests includedMargi Clarke,Toyah Willcox,Brett Anderson,andJon Savage.To coincide with the broadcast the exhibition, Evil Queen was premiered at theWhitworth Art Gallery,Manchester. (Contact BFI for footage).

- Derek Jarman: Life as Art(2004): a film exploring Derek Jarman's life and films by 400Blows Productions/Andy Kimpton-Nye, featuring Tilda Swinton, Simon Fisher Turner, Chris Hobbs and narrated by John Quentin. Broadcast onSky Artsand screened at film festivals around the world, including Buenos Aires, Cork, London, Leeds, Philadelphia and Turin.

- Derek(2008): a biography of Jarman's life and work, directed byIsaac Julienand written and narrated byTilda Swinton.

- Red Duckies(2006):[57]Short film directed byLuke Seomoreand Joseph Bull, featuring a voice-over fromSimon Fisher Turnercommissioned byDazed & Confusedfor World Aids Day 2006.

- Delphinium: A Childhood Portrait of Derek Jarman(2009): a "stylized and lyrical coming-of-age" short film combining narrative and documentary elements directed byMatthew Mishorydepicting Jarman's "artistic, sexual, and political awakening in postwar England".[58]Jarman's surviving muse Keith Collins andSiouxsie and the BansheesfounderSteven Severinboth participated in the making of the film, which had its world premiere at the 2009 Reykjavik International Film Festival in Iceland, its UK premiere at theRaindance Film Festivalin London, and its California premiere at the 2010 Frameline International Film Festival in San Francisco. In 2011, the film was installed permanently in theBritish Film Institute'sNational Film Archivein London.

- The Gospel According to St Derek(Andy Kimpton-Nye/400Blows Productions, 2014): screened at the King's College Early Modern Exhibition, the Pacific Film Archive - Berkeley Art Museum, the Australian cinematheque and on the Guardian website, this 40 mins documentary bears witness to Derek Jarman’s unique approach to low-budget film-making and his near-alchemical ability to turn the base components of film-making in to artistic gold.

- Saintmaking: Derek Jarman and the Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence(2021): a documentary by Marco Alessi, commissioned byThe Guardianto commemorate the 30th anniversary of Jarman's canonisation into the first British living gay saint by the group of queer activist nuns, theSisters of Perpetual Indulgence.[59]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^Tony Peake,Derek Jarman: A Biography(Woodstock: Overlook Press, 1999), pp. 12–13.

- ^abcTony Peake,Derek Jarman: A Biography(Woodstock: Overlook Press, 1999), p. 13.

- ^Jim Ellis,Derek Jarman's Angelic Conversations(Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2009), pp. 200–1.

- ^Tony Peake,Derek Jarman: A Biography(Woodstock: Overlook Press, 1999), pp. 389–94, 532–33.

- ^Elizabeth Puttock's mother, Moselle, a daughter of Isaac Frederic Reuben, had Jewish ancestry. Tony Peake,Derek Jarman: A Biography(Woodstock: Overlook Press, 1999), p. 10

- ^Tony Peake,Derek Jarman: A Biography(Woodstock: Overlook Press, 1999), pp. 8–9.

- ^"Jarman, (Michael) Derek Elworthy (1942–1994), film-maker, painter, and campaigner for homosexual rights".Oxford Dictionary of National Biography(online ed.). Oxford University Press. 2004.doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/55051.Retrieved28 September2019.(Subscription orUK public library membershiprequired.)

- ^"Deaths England and Wales 1984–2006".Archived fromthe originalon 4 November 2015.Retrieved28 January2009.

- ^William Pencak (2002). "13. Blue:" Our Time Is the Passing of a Shadow "".The films of Derek Jarman.McFarland. p. 159.ISBN9780786414307.

To those familiar with his other films, Jarman reinforces his atheism and contempt for traditional Christianity, thereby re-emphasizing the point he just made – that "paradise" is "terrestrial" and is the fruit of human love.

- ^"Keith Collins obituary".the Guardian.2 September 2018.

- ^"Derek Jarman Blue Plaque unveiled in London today".Peter Tatchell Foundation.19 February 2019.Retrieved19 February2019.

- ^"17th Moscow International Film Festival (1991)".MIFF.Archived fromthe originalon 3 April 2014.Retrieved4 March2013.

- ^"Toby Mott".IMDb.Retrieved27 August2012.

- ^Turning to Derek Jarman|Current|The Criterion Collection

- ^"Derek Jarman".UCL Campaign.9 February 2019.Retrieved10 March2020.

- ^Jubilee (1978)|The Criterion Collection

- ^Anarchy in the UK: Derek Jarman’s Jubilee (1978) Revisited,Julian Upton, Bright Lights Film Journal, Portland, OR, 1 October 2000.Retrieved: 1 January 2015.

- ^adamscovell (1 June 2015)."Alchemical Magic in Derek Jarman's The Tempest (1979)".Celluloid Wicker Man.Retrieved10 March2020.

- ^"Revisiting Derek Jarman's Caravaggio".Bfi.Retrieved10 March2020.

- ^"Berlinale: 1986 Prize Winners".berlinale.de.Archived fromthe originalon 22 March 2016.Retrieved15 January2011.

- ^ab"Watch Derek Jarman's Daring 12-Minute Promo Film for Marianne Faithfull's 1979 Comeback Album Broken English (NSFW)".openculture. 6 April 2017.Retrieved20 August2018.

- ^abcdeSchneider, Martin (3 December 2013)."Derek Jarman's Videos for the Smith and Pet Shop Boys".12 March 2013.dangerousminds.net.Retrieved20 August2018.

- ^ab"'Blue', Derek Jarman, 1993 ".Tate.Retrieved10 March2020.

- ^"6 Things You Need To Know About Derek Jarman".BBC Radio 4.Archivedfrom the original on 23 April 2015.Retrieved18 January2021.

- ^Blue|Walker Art Center

- ^Blue - Centre Pompidou

- ^Blue. 1993. Directed by Derek Jarman|MoMA

- ^"Glitterbug:: Zeitgeist Films".zeitgeistfilms.Retrieved10 March2020.

- ^Soundtrack Mix #28: Forever Blue: An Ode to Derek Jarman on Notebook|MUBI

- ^Evil Queen: The Last Paintings,1994

- ^Garden Museum (4 July 2020)."DEREK JARMAN: MY GARDEN'S BOUNDARIES ARE THE HORIZON".

- ^The Guardian (21 July 2020)."Blooms with a view: Derek Jarman's magical garden gets a transplant".The Guardian.

- ^FRIEZE (3 September 2020)."The Worlds of Derek Jarman's Garden".

- ^Jarman, Derek, and Shaun Allen. Dancing Ledge. Minneapolis: Minn., 2010. Print.

- ^"Robin Rimbaud – The Garden Is Full of Metal – Homage To Derek Jarman".Discogs.1997.Retrieved20 August2018.

- ^"Harold Budd – The Art of Mirrors (after Derek Jarman)".youtube. 26 October 2013.Archivedfrom the original on 11 December 2021.Retrieved20 August2018.

- ^"The Quietus | Reviews | Peter".The Quietus.Retrieved5 May2021.

- ^Coil – Themes For Derek Jarman's Blue (1993, Blue, Vinyl),1993,retrieved5 May2021

- ^"Peter" Sleazy "Christopherson* - Live At L' Etrange Festival 2004 - The Art Of Mirrors (Homage To Derek Jarman)".Discogs.Retrieved5 May2021.

- ^Simoneau·Music·March 3 (3 March 2020)."Video premiere: Romain Frequency - 'Perfect Blue'".Kaltblut Magazine.Retrieved5 May2021.

{{cite web}}:CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^Frank, Paula (17 February 2020)."Romain Frequency: Research on a Nameless Colour".Fourculture Magazine.Retrieved5 May2021.

- ^The Clearing,retrieved23 March2020

- ^Kenny, Glenn (4 August 2016)."Review: Dim All the Lights, Again: 'Will You Dance With Me?'".The New York Times.

- ^abcdefgh"the making of: Derek Jarman's Music Videos".greg.org. 4 March 2008.Retrieved15 July2012.

- ^"Throbbing Gristle –" T.G. psychic rally in Heaven "".mvdbase. Archived fromthe originalon 4 March 2016.Retrieved15 July2012.

- ^abc"Derek Jarman's music videos".Johncoulthart. 4 February 2012.Retrieved15 July2012.

- ^"Wang Chung –" Dance hall days [version 1: home movie footage] "".mvdbase. 12 November 1983. Archived fromthe originalon 3 March 2016.Retrieved15 July2012.

- ^Peake, Tony. 1999.Derek Jarman: A Biography.New York: The Overlook Press/Little, Brown. pg. 312: listed as "Steve Hale's 'Touch the Radio, Dance!'"

- ^"Marc Almond –" Tenderness is a weakness "".mvdbase. Archived fromthe originalon 3 March 2016.Retrieved15 July2012.

- ^"Bryan Ferry –" Windswept "".mvdbase. Archived fromthe originalon 4 March 2016.Retrieved15 July2012.

- ^"the Smiths –" The Queen is dead [version 2: film] "".mvdbase. Archived fromthe originalon 20 August 2018.Retrieved15 July2012.

- ^"the Smiths –" Ask [version 1] "".mvdbase. Archived fromthe originalon 20 August 2018.Retrieved15 July2012.

- ^"Pet Shop Boys –" Violence "".mvdbase. Archived fromthe originalon 20 August 2018.Retrieved15 July2012.

- ^"Suede –" The next life "".mvdbase. 29 March 1993. Archived fromthe originalon 4 March 2016.Retrieved15 July2012.

- ^"Patti Smith –" Memorial tribute "".mvdbase. Archived fromthe originalon 4 March 2016.Retrieved15 July2012.

- ^abcdefFrom the programme to the production ofWaiting for Godot

- ^Queer Cinema in America: An Encyclopedia of LGBTQ Films, Characters and Stories - Google Books (pg.147)

- ^"Delphinium: A Childhood Portrait of Derek Jarman | Raindance Film Festival 2009".Raindance.co.uk. 11 October 2009.Retrieved15 July2012.

- ^"Saintmaking: Derek Jarman and the Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence".theguardian. 22 September 2021.Retrieved7 November2021.

Further reading

[edit]- Robert Mills,Derek Jarman's Medieval Modern(D.S. Brewer, 2018),ISBN9781843844938

- Niall Richardson, 'The Queer Cinema of Derek Jarman: Critical and Cultural Readings' (I.B. Tauris, 2009)

- Michael Charlesworth,Derek Jarman(Reaktion, 2011)

- Martin Frey.Derek Jarman – Moving Pictures of a Painter.(INGRAM Content Group Inc., 2016),ISBN978-3-200-04494-4

- Steven Dillon.Derek Jarman and Lyric Film: The Mirror and the Sea.(2004).

- Tony Peake.Derek Jarman(Little, Brown & Co, 2000). 600-page biography.

- Michael O'Pray.Derek Jarman: Dreams of England.(British Film Institute,1996).

- Howard Sooley.Derek Jarman's Garden.(Thames & Hudson, 1995).

- Derek Jarman. 'Modern Nature' (Diaries 1989–1990)

- Derek Jarman. 'Smiling in Slow Motion' (Diaries 1991–1994)

- Derek Jarman. 'Dancing Ledge' (Memoir.ISBN0-8166744-9-3)

- 'Evil Queen' exhibition catalogue. Foreword by Mark JordanISBN0-9524356-0-8

- Derek Jarman. 'At Your Own Risk' (Memoir, Thames & Hudson, 1991)ISBN0099222914

- Judith Noble. "The Wedding of Light and Matter: Alchemy and Magic in the Films of Derek Jarman." InVisions of Enchantment: Occultism, Magic, and Visual Culture,eds. Daniel Zamani, Judith Noble, and Merlin Cox (London: Fulgur Press, 2019), pp. 168–181

External links

[edit]- Bibliography of books and articles about Jarmanvia UC Berkeley Media Resources center

- Derek Jarman biography and creditsat theBFI'sScreenonline

- Derek Jarman: Radical Traditionalist

- Preserving A Harlequin– a Jarman retrospective by Nick Clapson

- Derek JarmanatIMDb

- Portraits of Derek Jarmanat theNational Portrait Gallery, London

- Photographs of Prospect Cottage&garden detailsatFlickr

- Derek Jarman; On lyrical love and dedication

- Audio recording of Derek Jarman interviewed by Ken Campbell at the ICA, London, 7 February 1984

- Link to correspondence between Derek Jarman and Angelique Rockas

- Time is away showonNTS Radio.

- 1942 births

- 1994 deaths

- 20th-century atheists

- 20th-century English male artists

- 20th-century English diarists

- 20th-century English screenwriters

- 20th-century English LGBT people

- 20th-century English poets

- AIDS-related deaths in England

- Alumni of King's College London

- Alumni of the Slade School of Fine Art

- Artists from London

- BAFTA Outstanding British Contribution to Cinema Award

- English writers on atheism

- English experimental filmmakers

- English gardeners

- English gay writers

- English gay artists

- English health activists

- English male screenwriters

- English music video directors

- English people of Jewish descent

- English people of New Zealand descent

- Film directors from London

- Gay memoirists

- Gay screenwriters

- British HIV/AIDS activists

- British LGBT film directors

- English LGBT rights activists

- English LGBT screenwriters

- LGBT people from London

- People educated at Canford School

- People educated at Walhampton School and Hordle House School

- People from Northwood, London

- Writers from the London Borough of Hillingdon

- Collage filmmakers