History of science

| Part ofa serieson |

| Science |

|---|

Thehistory of sciencecovers the development ofsciencefromancient timesto thepresent.It encompasses all three majorbranches of science:natural,social,andformal.[1]Protoscience,early sciences,and natural philosophies such asalchemyandastrologyduring theBronze Age,Iron Age,classical antiquity,and theMiddle Agesdeclined during theearly modern periodafter the establishment of formal disciplines ofscience in the Age of Enlightenment.

Science's earliest roots can be traced toAncient EgyptandMesopotamiaaround 3000 to 1200BCE.[2][3]These civilizations' contributions tomathematics,astronomy,andmedicineinfluenced later Greeknatural philosophyofclassical antiquity,wherein formal attempts were made to provide explanations of events in thephysical worldbased on natural causes.[2][3]After thefall of the Western Roman Empire,knowledge ofGreek conceptions of the worlddeteriorated inLatin-speakingWestern Europeduring the early centuries (400 to 1000 CE) ofthe Middle Ages,[4]but continued to thrive in theGreek-speakingByzantine Empire.Aided by translations of Greek texts, theHellenisticworldview was preserved and absorbed into theArabic-speakingMuslim worldduring theIslamic Golden Age.[5]The recovery and assimilation ofGreek worksandIslamic inquiriesinto Western Europe from the 10th to 13th century revived the learning of natural philosophy in the West.[4][6]Traditions of early science were also developed inancient Indiaand separately inancient China,theChinese modelhaving influencedVietnam,KoreaandJapanbeforeWestern exploration.[7]Among thePre-Columbianpeoples ofMesoamerica,theZapotec civilizationestablished their first known traditions of astronomy and mathematics forproducing calendars,followed by other civilizations such as theMaya.

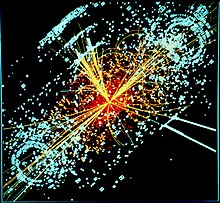

Natural philosophy was transformed during theScientific Revolutionin 16th- to 17th-century Europe,[8][9][10]asnew ideas and discoveriesdeparted fromprevious Greek conceptionsand traditions.[11][12][13][14]The New Science that emerged was moremechanisticin its worldview, more integrated with mathematics, and more reliable and open as its knowledge was based on a newly definedscientific method.[12][15][16]More "revolutions" in subsequent centuries soon followed. Thechemical revolutionof the 18th century, for instance, introduced new quantitative methods and measurements forchemistry.[17]In the19th century,new perspectives regarding theconservation of energy,age of Earth,andevolutioncame into focus.[18][19][20][21][22][23]And in the 20th century, new discoveries ingeneticsandphysicslaid the foundations for new sub disciplines such asmolecular biologyandparticle physics.[24][25]Moreover, industrial and military concerns as well as the increasing complexity of new research endeavors ushered in the era of "big science,"particularly afterWorld War II.[24][25][26]

Approaches to history of science

[edit]The nature of the history of science is a topic of debate (as is, by implication, the definition of science itself). The history of science is often seen as a linear story of progress[27] but historians have come to see the story as more complex.[28][29][30] Alfred Edward Taylorhas characterised lean periods in the advance of scientific discovery as "periodical bankruptcies of science".[31]

Science is a human activity, and scientific contributions have come from people from a wide range of different backgrounds and cultures. Historians of science increasingly see their field as part of a global history of exchange, conflict and collaboration.[32]

Therelationship between science and religionhas been variously characterized in terms of "conflict", "harmony", "complexity", and "mutual independence", among others. Events in Europe such as theGalileo affairof the early-17th century – associated with the scientific revolution and theAge of Enlightenment– led scholars such asJohn William Draperto postulate (c. 1874) aconflict thesis,suggesting that religion and science have been in conflict methodologically, factually and politically throughout history. The "conflict thesis" has since lost favor among the majority of contemporary scientists and historians of science.[33][34][35]However, some contemporary philosophers and scientists, such asRichard Dawkins,[36]still subscribe to this thesis.

Historians have emphasized[citation needed]that trust is necessary for agreement on claims about nature. In this light, the 1660 establishment of theRoyal Societyand its code of experiment – trustworthy because witnessed by its members – has become animportant chapterin thehistoriographyof science.[37]Many people in modern history (typicallywomenand persons of color) were excluded from elite scientific communities andcharacterized by the science establishment as inferior.Historians in the 1980s and 1990s described the structural barriers to participation and began to recover the contributions of overlooked individuals.[38][39]Historians have also investigated the mundane practices of science such as fieldwork and specimen collection,[40]correspondence,[41]drawing,[42]record-keeping,[43]and the use of laboratory and field equipment.[44]

Prehistoric times

[edit]Inprehistorictimes, knowledge and technique were passed from generation to generation in anoral tradition.For instance, the domestication ofmaizefor agriculture has been dated to about 9,000 years ago in southernMexico,before the development ofwriting systems.[45][46][47]Similarly,archaeologicalevidence indicates the development ofastronomicalknowledge in preliterate societies.[48][49]

The oral tradition of preliterate societies had several features, the first of which was its fluidity.[2]New information was constantly absorbed and adjusted to new circumstances or community needs. There were no archives or reports. This fluidity was closely related to the practical need to explain and justify a present state of affairs.[2]Another feature was the tendency to describe the universe as just sky and earth, with a potentialunderworld.They were also prone to identify causes with beginnings, thereby providing a historical origin with an explanation. There was also a reliance on a "medicine man"or"wise woman"for healing, knowledge of divine or demonic causes of diseases, and in more extreme cases, for rituals such asexorcism,divination,songs, andincantations.[2]Finally, there was an inclination to unquestioningly accept explanations that might be deemed implausible in more modern times while at the same time not being aware that such credulous behaviors could have posed problems.[2]

The development of writing enabled humans to store and communicate knowledge across generations with much greater accuracy. Its invention was a prerequisite for the development of philosophy and laterscience in ancient times.[2]Moreover, the extent to which philosophy and science would flourish in ancient times depended on the efficiency of a writing system (e.g., use of Alpha bets).[2]

Earliest roots in the Ancient Near East

[edit]The earliest roots of science can be traced to theAncient Near East,in particularAncient EgyptandMesopotamiain around 3000 to 1200 BCE.[2]

Ancient Egypt

[edit]Number system and geometry

[edit]Starting in around 3000 BCE, the ancient Egyptians developed a numbering system that was decimal in character and had oriented their knowledge of geometry to solving practical problems such as those of surveyors and builders.[2]Their development ofgeometrywas itself a necessary development ofsurveyingto preserve the layout and ownership offarmland,which was flooded annually by theNileRiver. The 3-4-5right triangleand other rules ofgeometrywere used to build rectilinear structures, and the post and lintel architecture of Egypt.

Disease and healing

[edit]

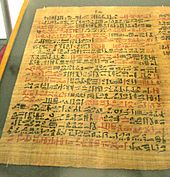

Egypt was also a center ofalchemyresearch for much of theMediterranean.Based on themedical papyriwritten in the 2500–1200 BCE, the ancient Egyptians believed that disease was mainly caused by the invasion of bodies by evil forces or spirits.[2]Thus, in addition to usingmedicines,their healing therapies includedprayer,incantation,and ritual.[2]TheEbers Papyrus,written in around 1600 BCE, contains medical recipes for treating diseases related to the eyes, mouth, skin, internal organs, and extremities, as well as abscesses, wounds, burns, ulcers, swollen glands, tumors, headaches, and even bad breath. TheEdwin Smith papyrus,written at about the same time, contains a surgical manual for treating wounds, fractures, and dislocations. The Egyptians believed that the effectiveness of their medicines depended on the preparation and administration under appropriate rituals.[2]Medical historians believe that ancient Egyptian pharmacology, for example, was largely ineffective.[50]Both the Ebers and Edwin Smith papyri applied the following components to the treatment of disease: examination, diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis,[51]which display strong parallels to the basicempirical methodof science and, according to G.E.R. Lloyd,[52]played a significant role in the development of this methodology.

Calendar

[edit]The ancient Egyptians even developed an official calendar that contained twelve months, thirty days each, and five days at the end of the year.[2]Unlike the Babylonian calendar or the ones used in Greek city-states at the time, the official Egyptian calendar was much simpler as it was fixed and did not takelunarand solar cycles into consideration.[2]

Mesopotamia

[edit]

The ancient Mesopotamians had extensive knowledge about thechemical propertiesof clay, sand, metal ore,bitumen,stone, and other natural materials, and applied this knowledge to practical use in manufacturingpottery,faience,glass, soap, metals,lime plaster,and waterproofing.Metallurgyrequired knowledge about the properties of metals. Nonetheless, the Mesopotamians seem to have had little interest in gathering information about the natural world for the mere sake of gathering information and were far more interested in studying the manner in which the gods had ordered theuniverse.Biology of non-human organisms was generally only written about in the context of mainstream academic disciplines.Animal physiologywas studied extensively for the purpose ofdivination;the anatomy of theliver,which was seen as an important organ inharuspicy,was studied in particularly intensive detail.Animal behaviorwas also studied for divinatory purposes. Most information about the training and domestication of animals was probably transmitted orally without being written down, but one text dealing with the training of horses has survived.[53]

Mesopotamian medicine

[edit]The ancientMesopotamianshad no distinction between "rational science" andmagic.[54][55][56]When a person became ill, doctors prescribed magical formulas to be recited as well as medicinal treatments.[54][55][56][53]The earliest medical prescriptions appear inSumerianduring theThird Dynasty of Ur(c.2112 BCE –c.2004 BCE).[57]The most extensiveBabylonianmedical text, however, is theDiagnostic Handbookwritten by theummânū,or chief scholar,Esagil-kin-apliofBorsippa,[58]during the reign of the Babylonian kingAdad-apla-iddina(1069–1046 BCE).[59]InEast Semiticcultures, the main medicinal authority was a kind of exorcist-healer known as anāšipu.[54][55][56]The profession was generally passed down from father to son and was held in extremely high regard.[54]Of less frequent recourse was another kind of healer known as anasu,who corresponds more closely to a modern physician and treated physical symptoms using primarilyfolk remediescomposed of various herbs, animal products, and minerals, as well as potions, enemas, and ointments orpoultices.These physicians, who could be either male or female, also dressed wounds, set limbs, and performed simple surgeries. The ancient Mesopotamians also practicedprophylaxisand took measures to prevent the spread of disease.[53]

Astronomy and celestial divination

[edit]

InBabylonian astronomy,records of the motions of thestars,planets,and themoonare left on thousands ofclay tabletscreated byscribes.Even today, astronomical periods identified by Mesopotamian proto-scientists are still widely used inWestern calendarssuch as thesolar yearand thelunar month.Using this data, they developed mathematical methods to compute the changing length of daylight in the course of the year, predict the appearances and disappearances of the Moon and planets, and eclipses of the Sun and Moon. Only a few astronomers' names are known, such as that ofKidinnu,aChaldeanastronomer and mathematician. Kiddinu's value for the solar year is in use for today's calendars. Babylonian astronomy was "the first and highly successful attempt at giving a refined mathematical description of astronomical phenomena." According to the historian A. Aaboe, "all subsequent varieties of scientific astronomy, in the Hellenistic world, in India, in Islam, and in the West—if not indeed all subsequent endeavour in the exact sciences—depend upon Babylonian astronomy in decisive and fundamental ways."[60]

To theBabyloniansand otherNear Easterncultures, messages from the gods or omens were concealed in all natural phenomena that could be deciphered and interpreted by those who are adept.[2]Hence, it was believed that the gods could speak through all terrestrial objects (e.g., animal entrails, dreams, malformed births, or even the color of a dog urinating on a person) and celestial phenomena.[2]Moreover, Babylonian astrology was inseparable from Babylonian astronomy.

Mathematics

[edit]The MesopotamiancuneiformtabletPlimpton 322,dating to the eighteenth-century BCE, records a number ofPythagorean triplets(3,4,5) (5,12,13)...,[61]hinting that the ancient Mesopotamians might have been aware of thePythagorean theoremover a millennium before Pythagoras.[62][63][64]

Ancient and medieval South Asia and East Asia

[edit]Mathematical achievements from Mesopotamia had some influence on the development of mathematics in India, and there were confirmed transmissions of mathematical ideas between India and China, which were bidirectional.[65]Nevertheless, the mathematical and scientific achievements in India and particularly in China occurred largely independently[66]from those of Europe and the confirmed early influences that these two civilizations had on the development of science in Europe in the pre-modern era were indirect, with Mesopotamia and later the Islamic World acting as intermediaries.[65]The arrival of modern science, which grew out of theScientific Revolution,in India and China and the greater Asian region in general can be traced to the scientific activities of Jesuit missionaries who were interested in studying the region'sfloraandfaunaduring the 16th to 17th century.[67]

India

[edit]Mathematics

[edit]

The earliest traces of mathematical knowledge in the Indian subcontinent appear with theIndus Valley Civilisation(c. 4th millennium BCE ~ c. 3rd millennium BCE). The people of this civilization made bricks whose dimensions were in the proportion 4:2:1, which is favorable for the stability of a brick structure.[68]They also tried to standardize measurement of length to a high degree of accuracy. They designed a ruler—theMohenjo-daro ruler—whose unit of length (approximately 1.32 inches or 3.4 centimeters) was divided into ten equal parts. Bricks manufactured in ancient Mohenjo-daro often had dimensions that were integral multiples of this unit of length.[69]

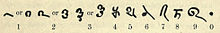

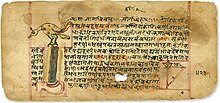

TheBakhshali manuscriptcontains problems involvingarithmetic,algebraandgeometry,includingmensuration.The topics covered include fractions, square roots,arithmeticandgeometric progressions,solutions of simple equations,simultaneous linear equations,quadratic equationsandindeterminate equationsof the second degree.[70]In the 3rd century BCE,Pingalapresents thePingala-sutras,the earliest known treatise onSanskrit prosody.[71]He also presents a numerical system by adding one to the sum ofplace values.[72]Pingala's work also includes material related to theFibonacci numbers,calledmātrāmeru.[73]

Indian astronomer and mathematicianAryabhata(476–550), in hisAryabhatiya(499) introduced thesinefunction intrigonometryand the number 0 [mathematics] . In 628 CE,Brahmaguptasuggested thatgravitywas a force of attraction.[74][75]He also lucidly explained the use ofzeroas both a placeholder and adecimal digit,along with theHindu–Arabic numeral systemnow used universally throughout the world.Arabictranslations of the two astronomers' texts were soon available in theIslamic world,introducing what would becomeArabic numeralsto the Islamic world by the 9th century.[76][77]

Narayana Pandita(Sanskrit:नारायण पण्डित) (1340–1400[78]) was an Indianmathematician.Plofkerwrites that his texts were the most significant Sanskrit mathematics treatises after those ofBhaskara II,other than theKerala school.[79]: 52 He wrote theGanita Kaumudi(lit. "Moonlight of mathematics" ) in 1356 about mathematical operations.[80]The work anticipated many developments incombinatorics.

During the 14th–16th centuries, theKerala school of astronomy and mathematicsmade significant advances in astronomy and especially mathematics, including fields such as trigonometry and analysis. In particular,Madhava of Sangamagramaled advancement inanalysisby providing the infinite and taylor series expansion of some trigonometric functions and pi approximation.[81]Parameshvara(1380–1460), presents a case of the Mean Value theorem in his commentaries onGovindasvāmiandBhāskara II.[82]TheYuktibhāṣāwas written byJyeshtadevain 1530.[83]

Astronomy

[edit]

The first textual mention of astronomical concepts comes from theVedas,religious literature of India.[84]According to Sarma (2008): "One finds in theRigvedaintelligent speculations about the genesis of the universe from nonexistence, the configuration of the universe, thespherical self-supporting earth,and the year of 360 days divided into 12 equal parts of 30 days each with a periodical intercalary month. ".[84]

The first 12 chapters of theSiddhanta Shiromani,written byBhāskarain the 12th century, cover topics such as: mean longitudes of the planets; true longitudes of the planets; the three problems of diurnal rotation; syzygies; lunar eclipses; solar eclipses; latitudes of the planets; risings and settings; the moon's crescent; conjunctions of the planets with each other; conjunctions of the planets with the fixed stars; and the patas of the sun and moon. The 13 chapters of the second part cover the nature of the sphere, as well as significant astronomical and trigonometric calculations based on it.

In theTantrasangrahatreatise,Nilakantha Somayaji's updated the Aryabhatan model for the interior planets, Mercury, and Venus and the equation that he specified for the center of these planets was more accurate than the ones in European or Islamic astronomy until the time ofJohannes Keplerin the 17th century.[85]Jai Singh IIofJaipurconstructed fiveobservatoriescalledJantar Mantarsin total, inNew Delhi,Jaipur,Ujjain,MathuraandVaranasi;they were completed between 1724 and 1735.[86]

Grammar

[edit]Some of the earliest linguistic activities can be found inIron Age India(1st millennium BCE) with the analysis ofSanskritfor the purpose of the correct recitation and interpretation ofVedictexts. The most notable grammarian of Sanskrit wasPāṇini(c. 520–460 BCE), whose grammar formulates close to 4,000 rules for Sanskrit. Inherent in his analytic approach are the concepts of thephoneme,themorphemeand theroot.TheTolkāppiyamtext, composed in the early centuries of the common era,[87]is a comprehensive text on Tamil grammar, which includes sutras on orthography, phonology, etymology, morphology, semantics, prosody, sentence structure and the significance of context in language.

Medicine

[edit]

Findings fromNeolithicgraveyards in what is now Pakistan show evidence of proto-dentistry among an early farming culture.[88]The ancient textSuśrutasamhitāofSuśrutadescribes procedures on various forms of surgery, includingrhinoplasty,the repair of torn ear lobes, perineallithotomy,cataract surgery, and several other excisions and other surgical procedures.[89][90]TheCharaka SamhitaofCharakadescribes ancient theories on human body,etiology,symptomologyandtherapeuticsfor a wide range of diseases.[91]It also includes sections on the importance of diet, hygiene, prevention, medical education, and the teamwork of a physician, nurse and patient necessary for recovery to health.[92][93][94]

Politics and state

[edit]An ancient Indian treatise onstatecraft,economicpolicy andmilitary strategyby Kautilya[95]andViṣhṇugupta,[96]who are traditionally identified withChāṇakya(c. 350–283 BCE). In this treatise, the behaviors and relationships of the people, the King, the State, the Government Superintendents, Courtiers, Enemies, Invaders, and Corporations are analyzed and documented.Roger Boeschedescribes theArthaśāstraas "a book of political realism, a book analyzing how the political world does work and not very often stating how it ought to work, a book that frequently discloses to a king what calculating and sometimes brutal measures he must carry out to preserve the state and the common good."[97]

Logic

[edit]The development ofIndian logicdates back to theChandahsutraof Pingala andanviksikiof Medhatithi Gautama (c. 6th century BCE); theSanskrit grammarrules ofPāṇini(c. 5th century BCE); theVaisheshikaschool's analysis ofatomism(c. 6th century BCE to 2nd century BCE); the analysis ofinferencebyGotama(c. 6th century BC to 2nd century CE), founder of theNyayaschool ofHindu philosophy;and thetetralemmaofNagarjuna(c. 2nd century CE).

Indianlogic stands as one of the three original traditions oflogic,alongside theGreekand theChinese logic.The Indian tradition continued to develop through early to modern times, in the form of theNavya-Nyāyaschool of logic.

In the 2nd century, theBuddhistphilosopherNagarjunarefined theCatuskotiform of logic. The Catuskoti is also often glossedTetralemma(Greek) which is the name for a largely comparable, but not equatable, 'four corner argument' within the tradition ofClassical logic.

Navya-Nyāya developed a sophisticated language and conceptual scheme that allowed it to raise, analyse, and solve problems in logic and epistemology. It systematised all the Nyāya concepts into four main categories: sense or perception (pratyakşa), inference (anumāna), comparison or similarity (upamāna), and testimony (sound or word; śabda).

China

[edit]

Chinese mathematics

[edit]From the earliest the Chinese used a positional decimal system on counting boards in order to calculate. To express 10, a single rod is placed in the second box from the right. The spoken language uses a similar system to English: e.g. four thousand two hundred and seven. No symbol was used for zero. By the 1st century BCE, negative numbers and decimal fractions were in use andThe Nine Chapters on the Mathematical Artincluded methods for extracting higher order roots byHorner's methodand solving linear equations and byPythagoras' theorem.Cubic equations were solved in theTang dynastyand solutions of equations of order higher than 3 appeared in print in 1245 CE byCh'in Chiu-shao.Pascal's trianglefor binomial coefficients was described around 1100 byJia Xian.[98]

Although the first attempts at an axiomatization of geometry appear in theMohistcanon in 330 BCE,Liu Huideveloped algebraic methods in geometry in the 3rd century CE and also calculatedpito 5 significant figures. In 480,Zu Chongzhiimproved this by discovering the ratiowhich remained the most accurate value for 1200 years.

Astronomical observations

[edit]

Astronomical observations from China constitute the longest continuous sequence from any civilization and include records of sunspots (112 records from 364 BCE), supernovas (1054), lunar and solar eclipses. By the 12th century, they could reasonably accurately make predictions of eclipses, but the knowledge of this was lost during the Ming dynasty, so that the JesuitMatteo Riccigained much favor in 1601 by his predictions.[100][incomplete short citation]By 635 Chinese astronomers had observed that the tails of comets always point away from the sun.

From antiquity, the Chinese used an equatorial system for describing the skies and a star map from 940 was drawn using a cylindrical (Mercator) projection. The use of anarmillary sphereis recorded from the 4th century BCE and a sphere permanently mounted in equatorial axis from 52 BCE. In 125 CEZhang Hengused water power to rotate the sphere in real time. This included rings for the meridian and ecliptic. By 1270 they had incorporated the principles of the Arabtorquetum.

In theSong Empire(960–1279) ofImperial China,Chinesescholar-officialsunearthed, studied, and cataloged ancient artifacts.

Inventions

[edit]

To better prepare for calamities, Zhang Heng invented aseismometerin 132 CE which provided instant alert to authorities in the capital Luoyang that an earthquake had occurred in a location indicated by a specificcardinal or ordinal direction.[101][102]Although no tremors could be felt in the capital when Zhang told the court that an earthquake had just occurred in the northwest, a message came soon afterwards that an earthquake had indeed struck 400 to 500 km (250 to 310 mi) northwest of Luoyang (in what is now modernGansu).[103]Zhang called his device the 'instrument for measuring the seasonal winds and the movements of the Earth' (Houfeng didong yi máy đo địa chấn ), so-named because he and others thought that earthquakes were most likely caused by the enormous compression of trapped air.[104]

There are many notable contributors to early Chinese disciplines, inventions, and practices throughout the ages. One of the best examples would be the medieval Song ChineseShen Kuo(1031–1095), apolymathand statesman who was the first to describe themagnetic-needlecompassused fornavigation,discovered the concept oftrue north,improved the design of the astronomicalgnomon,armillary sphere,sight tube, andclepsydra,and described the use ofdrydocksto repair boats. After observing the natural process of the inundation ofsiltand the find ofmarinefossilsin theTaihang Mountains(hundreds of miles from the Pacific Ocean), Shen Kuo devised a theory of land formation, orgeomorphology.He also adopted a theory of gradualclimate changein regions over time, after observingpetrifiedbamboofound underground atYan'an,Shaanxiprovince. If not for Shen Kuo's writing,[105]the architectural works ofYu Haowould be little known, along with the inventor ofmovable typeprinting,Bi Sheng(990–1051). Shen's contemporarySu Song(1020–1101) was also a brilliant polymath, an astronomer who created a celestial atlas of star maps, wrote a treatise related tobotany,zoology,mineralogy,andmetallurgy,and had erected a largeastronomicalclocktowerinKaifengcity in 1088. To operate the crowningarmillary sphere,his clocktower featured anescapementmechanism and the world's oldest known use of an endless power-transmittingchain drive.[106]

TheJesuit China missionsof the 16th and 17th centuries "learned to appreciate the scientific achievements of this ancient culture and made them known in Europe. Through their correspondence European scientists first learned about the Chinese science and culture."[107]Western academic thought on the history of Chinese technology and science was galvanized by the work ofJoseph Needhamand the Needham Research Institute. Among the technological accomplishments of China were, according to the British scholar Needham, thewater-poweredcelestial globe(Zhang Heng),[108]dry docks,slidingcalipers,the double-actionpiston pump,[108]theblast furnace,[109]the multi-tubeseed drill,thewheelbarrow,[109]thesuspension bridge,[109]thewinnowing machine,[108]gunpowder,[109]theraised-relief map,toilet paper,[109]the efficient harness,[108]along with contributions inlogic,astronomy,medicine,and other fields.

However, cultural factors prevented these Chinese achievements from developing into "modern science". According to Needham, it may have been the religious and philosophical framework of Chinese intellectuals which made them unable to accept the ideas of laws of nature:

It was not that there was no order in nature for the Chinese, but rather that it was not an order ordained by a rational personal being, and hence there was no conviction that rational personal beings would be able to spell out in their lesser earthly languages the divine code of laws which he had decreed aforetime. TheTaoists,indeed, would have scorned such an idea as being too naïve for the subtlety and complexity of the universe as they intuited it.[110]

Pre-Columbian Mesoamerica

[edit]

During theMiddle Formative Period(c. 900 BCE – c. 300 BCE) ofPre-ColumbianMesoamerica,theZapotec civilization,heavily influenced by theOlmec civilization,established the first knownfull writing systemof the region (possibly predated bythe OlmecCascajal Block),[111]as well as the first known astronomicalcalendar in Mesoamerica.[112][113]Following a period of initial urban development in thePreclassical period,theClassicMaya civilization(c. 250 CE – c. 900 CE) built on the shared heritage of the Olmecs by developing the most sophisticated systems ofwriting,astronomy,calendrical science,andmathematicsamong Mesoamerican peoples.[112]The Maya developed apositional numeral systemwith abase of 20that included the use ofzerofor constructing their calendars.[114][115]Maya writing, which was developed by 200 BCE, widespread by 100 BCE, and rootedin Olmecand Zapotec scripts, contains easily discernible calendar dates in the form oflogographsrepresenting numbers, coefficients, and calendar periods amounting to 20 days and even 20 years for tracking social, religious, political, and economic events in 360-day years.[116]

Classical antiquity and Greco-Roman science

[edit]The contributions of the Ancient Egyptians and Mesopotamians in the areas of astronomy, mathematics, and medicine had entered and shapedGreeknatural philosophyofclassical antiquity,whereby formal attempts were made to provide explanations of events in thephysical worldbased on natural causes.[2][3]Inquiries were also aimed at such practical goals such as establishing a reliable calendar or determining how to cure a variety of illnesses. The ancient people who were considered the firstscientistsmay have thought of themselves asnatural philosophers,as practitioners of a skilled profession (for example,physicians), or as followers of areligious tradition(for example,temple healers).

Pre-socratics

[edit]The earliestGreek philosophers,known as thepre-Socratics,[117]provided competing answers to the question found in the myths of their neighbors: "How did the orderedcosmosin which we live come to be? "[118]The pre-Socratic philosopherThales(640–546 BCE) ofMiletus,[119]identified by later authors such as Aristotle as the first of theIonian philosophers,[2]postulated non-supernatural explanations for natural phenomena. For example, that land floats on water and that earthquakes are caused by the agitation of the water upon which the land floats, rather than the god Poseidon.[120]Thales' studentPythagorasofSamosfounded thePythagorean school,which investigated mathematics for its own sake, and was the first to postulate that the Earth is spherical in shape.[121]Leucippus(5th century BCE) introducedatomism,the theory that allmatteris made of indivisible, imperishable units calledatoms.This was greatly expanded on by his pupilDemocritusand laterEpicurus.

Natural philosophy

[edit]

PlatoandAristotleproduced the first systematic discussions of natural philosophy, which did much to shape later investigations of nature. Their development ofdeductive reasoningwas of particular importance and usefulness to later scientific inquiry. Plato founded thePlatonic Academyin 387 BCE, whose motto was "Let none unversed in geometry enter here," and also turned out many notable philosophers. Plato's student Aristotle introducedempiricismand the notion that universal truths can be arrived at via observation and induction, thereby laying the foundations of the scientific method.[122]Aristotle also producedmany biological writingsthat were empirical in nature, focusing on biological causation and the diversity of life. He made countless observations of nature, especially the habits and attributes of plants and animals onLesbos,classified more than 540 animal species, and dissected at least 50.[123]Aristotle's writings profoundly influenced subsequentIslamicandEuropeanscholarship, though they were eventually superseded in theScientific Revolution.[124][125]

Aristotle also contributed to theories of the elements and the cosmos. He believed that thecelestial bodies(such as the planets and the Sun) had something called anunmoved moverthat put the celestial bodies in motion. Aristotle tried to explain everything through mathematics and physics, but sometimes explained things such as the motion of celestial bodies through a higher power such as God. Aristotle did not have the technological advancements that would have explained the motion of celestial bodies.[126]In addition, Aristotle had many views on the elements. He believed that everything was derived of the elements earth, water, air, fire, and lastly theAether.The Aether was a celestial element, and therefore made up the matter of the celestial bodies.[127]The elements of earth, water, air and fire were derived of a combination of two of the characteristics of hot, wet, cold, and dry, and all had their inevitable place and motion. The motion of these elements begins with earth being the closest to "the Earth," then water, air, fire, and finally Aether. In addition to the makeup of all things, Aristotle came up with theories as to why things did not return to their natural motion. He understood that water sits above earth, air above water, and fire above air in their natural state. He explained that although all elements must return to their natural state, the human body and other living things have a constraint on the elements – thus not allowing the elements making one who they are to return to their natural state.[128]

The important legacy of this period included substantial advances in factual knowledge, especially inanatomy,zoology,botany,mineralogy,geography,mathematicsandastronomy;an awareness of the importance of certain scientific problems, especially those related to the problem of change and its causes; and a recognition of the methodological importance of applying mathematics to natural phenomena and of undertaking empirical research.[129][119]In theHellenistic agescholars frequently employed the principles developed in earlier Greek thought: the application of mathematics and deliberate empirical research, in their scientific investigations.[130]Thus, clear unbroken lines of influence lead from ancientGreekandHellenistic philosophers,to medievalMuslim philosophersandscientists,to the EuropeanRenaissanceandEnlightenment,to the secularsciencesof the modern day. Neither reason nor inquiry began with the Ancient Greeks, but theSocratic methoddid, along with the idea ofForms,give great advances in geometry,logic,and the natural sciences. According toBenjamin Farrington,former professor ofClassicsatSwansea University:

- "Men were weighing for thousands of years beforeArchimedesworked out the laws of equilibrium; they must have had practical and intuitional knowledge of the principals involved. What Archimedes did was to sort out the theoretical implications of this practical knowledge and present the resulting body of knowledge as a logically coherent system. "

and again:

- "With astonishment we find ourselves on the threshold of modern science. Nor should it be supposed that by some trick of translation the extracts have been given an air of modernity. Far from it. The vocabulary of these writings and their style are the source from which our own vocabulary and style have been derived."[131]

Greek astronomy

[edit]

The astronomerAristarchus of Samoswas the first known person to propose a heliocentric model of theSolar System,while the geographerEratosthenesaccurately calculated the circumference of the Earth.Hipparchus(c. 190 – c. 120 BCE) produced the first systematicstar catalog.The level of achievement in Hellenistic astronomy andengineeringis impressively shown by theAntikythera mechanism(150–100 BCE), ananalog computerfor calculating the position of planets. Technological artifacts of similar complexity did not reappear until the 14th century, when mechanicalastronomical clocksappeared in Europe.[132]

Hellenistic medicine

[edit]There was not a defined societal structure for healthcare during the age of Hippocrates.[133]At that time, society was not organized and knowledgeable as people still relied on pure religious reasoning to explain illnesses.[133]Hippocrates introduced the first healthcare system based on science and clinical protocols.[134]Hippocrates' theories about physics and medicine helped pave the way in creating an organized medical structure for society.[134]Inmedicine,Hippocrates(c. 460 BC – c. 370 BCE) and his followers were the first to describe many diseases and medical conditions and developed theHippocratic Oathfor physicians, still relevant and in use today. Hippocrates' ideas are expressed inThe Hippocratic Corpus.The collection notes descriptions of medical philosophies and how disease and lifestyle choices reflect on the physical body.[134]Hippocrates influenced a Westernized, professional relationship among physician and patient.[135]Hippocratesis also known as "the Father of Medicine".[134]Herophilos(335–280 BCE) was the first to base his conclusions on dissection of the human body and to describe thenervous system.Galen(129 – c. 200 CE) performed many audacious operations—including brain and eyesurgeries— that were not tried again for almost two millennia.

Greek mathematics

[edit]

InHellenistic Egypt,the mathematicianEuclidlaid down the foundations ofmathematical rigorand introduced the concepts of definition, axiom, theorem and proof still in use today in hisElements,considered the most influential textbook ever written.[137]Archimedes,considered one of the greatest mathematicians of all time,[138]is credited with using themethod of exhaustionto calculate theareaunder the arc of aparabolawith thesummation of an infinite series,and gave a remarkably accurate approximation ofpi.[139]He is also known in physics for laying the foundations ofhydrostatics,statics,and the explanation of the principle of thelever.

Other developments

[edit]Theophrastuswrote some of the earliest descriptions of plants and animals, establishing the firsttaxonomyand looking at minerals in terms of their properties, such ashardness.Pliny the Elderproduced one of the largestencyclopediasof the natural world in 77 CE, and was a successor to Theophrastus. For example, he accurately describes theoctahedralshape of thediamondand noted that diamond dust is used byengraversto cut and polish other gems owing to its great hardness. His recognition of the importance ofcrystalshape is a precursor to moderncrystallography,while notes on other minerals presages mineralogy. He recognizes other minerals have characteristic crystal shapes, but in one example, confuses thecrystal habitwith the work oflapidaries.Pliny was the first to showamberwas a resin from pine trees, because of trapped insects within them.[140][141]

The development of archaeology has its roots in history and with those who were interested in the past, such as kings and queens who wanted to show past glories of their respective nations. The 5th-century-BCEGreek historianHerodotuswas the first scholar to systematically study the past and perhaps the first to examine artifacts.

Greek scholarship under Roman rule

[edit]During the rule of Rome, famous historians such asPolybius,LivyandPlutarchdocumented the rise of theRoman Republic,and the organization and histories of other nations, while statesmen likeJulius Caesar,Cicero, and others provided examples of the politics of the republic and Rome's empire and wars. The study of politics during this age was oriented toward understanding history, understanding methods of governing, and describing the operation of governments.

TheRoman conquest of Greecedid not diminish learning and culture in the Greek provinces.[142]On the contrary, the appreciation of Greek achievements in literature, philosophy, politics, and the arts by Rome'supper classcoincided with the increased prosperity of theRoman Empire.Greek settlements had existed in Italy for centuries and the ability to read and speak Greek was not uncommon in Italian cities such as Rome.[142]Moreover, the settlement of Greek scholars in Rome, whether voluntarily or as slaves, gave Romans access to teachers of Greek literature and philosophy. Conversely, young Roman scholars also studied abroad in Greece and upon their return to Rome, were able to convey Greek achievements to their Latin leadership.[142]And despite the translation of a few Greek texts into Latin, Roman scholars who aspired to the highest level did so using the Greek language. The Romanstatesmanand philosopherCicero(106 – 43 BCE) was a prime example. He had studied under Greek teachers in Rome and then in Athens andRhodes.He mastered considerable portions of Greek philosophy, wrote Latin treatises on several topics, and even wrote Greek commentaries of Plato'sTimaeusas well as a Latin translation of it, which has not survived.[142]

In the beginning, support for scholarship in Greek knowledge was almost entirely funded by the Roman upper class.[142]There were all sorts of arrangements, ranging from a talented scholar being attached to a wealthy household to owning educated Greek-speaking slaves.[142]In exchange, scholars who succeeded at the highest level had an obligation to provide advice or intellectual companionship to their Roman benefactors, or to even take care of their libraries. The less fortunate or accomplished ones would teach their children or perform menial tasks.[142]The level of detail and sophistication of Greek knowledge was adjusted to suit the interests of their Roman patrons. That meant popularizing Greek knowledge by presenting information that were of practical value such as medicine or logic (for courts and politics) but excluding subtle details of Greek metaphysics and epistemology. Beyond the basics, the Romans did not value natural philosophy and considered it an amusement for leisure time.[142]

Commentaries andencyclopediaswere the means by which Greek knowledge was popularized for Roman audiences.[142]The Greek scholarPosidonius(c. 135-c. 51 BCE), a native of Syria, wrote prolifically on history, geography, moral philosophy, and natural philosophy. He greatly influenced Latin writers such asMarcus Terentius Varro(116-27 BCE), who wrote the encyclopediaNine Books of Disciplines,which covered nine arts: grammar, rhetoric, logic, arithmetic, geometry, astronomy, musical theory, medicine, and architecture.[142]TheDisciplinesbecame a model for subsequent Roman encyclopedias and Varro's nine liberal arts were considered suitable education for a Roman gentleman. The first seven of Varro's nine arts would later define theseven liberal artsofmedieval schools.[142]The pinnacle of the popularization movement was the Roman scholarPliny the Elder(23/24–79 CE), a native of northern Italy, who wrote several books on the history of Rome and grammar. His most famous work was his voluminousNatural History.[142]

After the death of the Roman EmperorMarcus Aureliusin 180 CE, the favorable conditions for scholarship and learning in the Roman Empire were upended by political unrest, civil war, urban decay, and looming economic crisis.[142]In around 250 CE,barbariansbegan attacking and invading the Roman frontiers. These combined events led to a general decline in political and economic conditions. The living standards of the Roman upper class was severely impacted, and their loss ofleisurediminished scholarly pursuits.[142]Moreover, during the 3rd and 4th centuries CE, the Roman Empire was administratively divided into two halves:Greek East and Latin West.These administrative divisions weakened the intellectual contact between the two regions.[142]Eventually, both halves went their separate ways, with the Greek East becoming theByzantine Empire.[142]Christianitywas also steadily expanding during this time and soon became a major patron of education in the Latin West. Initially, the Christian church adopted some of the reasoning tools of Greek philosophy in the 2nd and 3rd centuries CE to defend its faith against sophisticated opponents.[142]Nevertheless, Greek philosophy received a mixed reception from leaders and adherents of the Christian faith.[142]Some such asTertullian(c. 155-c. 230 CE) were vehemently opposed to philosophy, denouncing it asheretic.Others such asAugustine of Hippo(354-430 CE) were ambivalent and defended Greek philosophy and science as the best ways to understand the natural world and therefore treated it as ahandmaiden(or servant) of religion.[142]Education in the West began its gradual decline, along with the rest ofWestern Roman Empire,due to invasions by Germanic tribes, civil unrest, and economic collapse. Contact with the classical tradition was lost in specific regions such asRoman Britainand northernGaulbut continued to exist in Rome, northern Italy, southern Gaul, Spain, andNorth Africa.[142]

Middle Ages

[edit]In the Middle Ages, the classical learning continued in three major linguistic cultures and civilizations: Greek (the Byzantine Empire), Arabic (the Islamic world), and Latin (Western Europe).

Byzantine Empire

[edit]

Preservation of Greek heritage

[edit]Thefall of the Western Roman Empireled to a deterioration of the classical tradition in the western part (orLatin West) of Europe during the 5th century. In contrast, the Byzantine Empire resisted the barbarian attacks and preserved and improved the learning.[143]

While the Byzantine Empire still held learning centers such asConstantinople,Alexandria and Antioch, Western Europe's knowledge was concentrated inmonasteriesuntil the development ofmedieval universitiesin the 12th centuries. The curriculum of monastic schools included the study of the few available ancient texts and of new works on practical subjects like medicine[144]and timekeeping.[145]

In the sixth century in the Byzantine Empire,Isidore of Miletuscompiled Archimedes' mathematical works in theArchimedes Palimpsest,where all Archimedes' mathematical contributions were collected and studied.

John Philoponus,another Byzantine scholar, was the first to question Aristotle's teaching of physics, introducing thetheory of impetus.[146][147]The theory of impetus was an auxiliary or secondary theory of Aristotelian dynamics, put forth initially to explain projectile motion against gravity. It is the intellectual precursor to the concepts of inertia, momentum and acceleration in classical mechanics.[148]The works of John Philoponus inspiredGalileo Galileiten centuries later.[149][150]

Collapse

[edit]During theFall of Constantinoplein 1453, a number of Greek scholars fled to North Italy in which they fueled the era later commonly known as the "Renaissance"as they brought with them a great deal of classical learning including an understanding of botany, medicine, and zoology. Byzantium also gave the West important inputs: John Philoponus' criticism of Aristotelian physics, and the works of Dioscorides.[151]

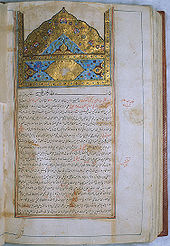

Islamic world

[edit]

This was the period (8th–14th century CE) of theIslamic Golden Agewhere commerce thrived, and new ideas and technologies emerged such as the importation ofpapermakingfrom China, which made the copying of manuscripts inexpensive.

Translations and Hellenization

[edit]The eastward transmission of Greek heritage to Western Asia was a slow and gradual process that spanned over a thousand years, beginning with the Asian conquests ofAlexander the Greatin 335 BCE to thefounding of Islam in the 7th century CE.[5]The birth and expansion of Islam during the 7th century was quickly followed by itsHellenization.Knowledge ofGreek conceptions of the worldwas preserved and absorbed into Islamic theology, law, culture, and commerce, which were aided by the translations of traditional Greek texts and someSyriacintermediary sources intoArabicduring the 8th–9th century.

Education and scholarly pursuits

[edit]

Madrasaswere centers for many different religious and scientific studies and were the culmination of different institutions such as mosques based around religious studies, housing for out-of-town visitors, and finally educational institutions focused on the natural sciences.[152]Unlike Western universities, students at a madrasa would learn from one specific teacher, who would issue a certificate at the completion of their studies called anIjazah.An Ijazah differs from a western university degree in many ways one being that it is issued by a single person rather than an institution, and another being that it is not an individual degree declaring adequate knowledge over broad subjects, but rather a license to teach and pass on a very specific set of texts.[153]Women were also allowed to attend madrasas, as both students and teachers, something not seen in high western education until the 1800s.[153]Madrasas were more than just academic centers. TheSuleymaniye Mosque,for example, was one of the earliest and most well-known madrasas, which was built bySuleiman the Magnificentin the 16th century.[154]The Suleymaniye Mosque was home to a hospital and medical college, a kitchen, and children's school, as well as serving as a temporary home for travelers.[154]

Higher education at a madrasa (or college) was focused on Islamic law and religious science and students had to engage in self-study for everything else.[5]And despite the occasional theological backlash, many Islamic scholars of science were able to conduct their work in relatively tolerant urban centers (e.g.,BaghdadandCairo) and were protected by powerful patrons.[5]They could also travel freely and exchange ideas as there were no political barriers within the unified Islamic state.[5]Islamic science during this time was primarily focused on the correction, extension, articulation, and application of Greek ideas to new problems.[5]

Advancements in mathematics

[edit]Most of the achievements by Islamic scholars during this period were in mathematics.[5]Arabic mathematicswas a direct descendant of Greek and Indian mathematics.[5]For instance, what is now known asArabic numeralsoriginally came from India, but Muslim mathematicians made several key refinements to the number system, such as the introduction ofdecimal pointnotation. Mathematicians such asMuhammad ibn Musa al-Khwarizmi(c. 780–850) gave his name to the concept of thealgorithm,while the termalgebrais derived fromal-jabr,the beginning of the title of one of his publications.[155]Islamic trigonometry continued from the works of Ptolemy'sAlmagestand IndianSiddhanta,from which they addedtrigonometric functions,drew up tables, and applied trignometry to spheres and planes. Many of their engineers, instruments makers, and surveyors contributed books in applied mathematics. It was inastronomywhere Islamic mathematicians made their greatest contributions.Al-Battani(c. 858–929) improved the measurements ofHipparchus,preserved in the translation ofPtolemy'sHè Megalè Syntaxis(The great treatise) translated asAlmagest.Al-Battani also improved the precision of the measurement of the precession of the Earth's axis. Corrections were made to Ptolemy'sgeocentric modelby al-Battani,Ibn al-Haytham,[156]Averroesand theMaragha astronomerssuch asNasir al-Din al-Tusi,Mu'ayyad al-Din al-UrdiandIbn al-Shatir.[157][158]

Scholars with geometric skills made significant improvements to the earlier classical texts on light and sight by Euclid, Aristotle, and Ptolemy.[5]The earliest surviving Arabic treatises were written in the 9th century byAbū Ishāq al-Kindī,Qustā ibn Lūqā,and (in fragmentary form) Ahmad ibn Isā. Later in the 11th century,Ibn al-Haytham(known as Alhazen in the West), a mathematician and astronomer, synthesized a new theory of vision based on the works of his predecessors.[5]His new theory included a complete system of geometrical optics, which was set in great detail in hisBook of Optics.[5][159]His book was translated into Latin and was relied upon as a principal source on the science of optics in Europe until the 17th century.[5]

Institutionalization of medicine

[edit]The medical sciences were prominently cultivated in the Islamic world.[5]The works of Greek medical theories, especially those of Galen, were translated into Arabic and there was an outpouring of medical texts by Islamic physicians, which were aimed at organizing, elaborating, and disseminating classical medical knowledge.[5]Medical specialtiesstarted to emerge, such as those involved in the treatment of eye diseases such ascataracts.Ibn Sina (known asAvicennain the West, c. 980–1037) was a prolific Persian medical encyclopedist[160]wrote extensively on medicine,[161][162]with his two most notable works in medicine being theKitāb al-shifāʾ( "Book of Healing" ) andThe Canon of Medicine,both of which were used as standard medicinal texts in both the Muslim world and in Europe well into the 17th century. Amongst his many contributions are the discovery of the contagious nature of infectious diseases,[161]and the introduction of clinical pharmacology.[163]Institutionalization of medicine was another important achievement in the Islamic world. Although hospitals as an institution for the sick emerged in the Byzantium empire, the model of institutionalized medicine for all social classes was extensive in the Islamic empire and was scattered throughout. In addition to treating patients, physicians could teach apprentice physicians, as well write and do research. The discovery of the pulmonary transit of blood in the human body byIbn al-Nafisoccurred in a hospital setting.[5]

Decline

[edit]Islamic science began its decline in the 12th–13th century, before theRenaissancein Europe, due in part to theChristian reconquest of Spainand theMongol conquestsin the East in the 11th–13th century. The Mongolssacked Baghdad,capital of theAbbasid Caliphate,in 1258, which ended theAbbasid empire.[5][164]Nevertheless, many of the conquerors became patrons of the sciences.Hulagu Khan,for example, who led the siege of Baghdad, became a patron of theMaragheh observatory.[5]Islamic astronomy continued to flourish into the 16th century.[5]

Western Europe

[edit]

By the eleventh century, most of Europe had become Christian; stronger monarchies emerged; borders were restored; technological developments and agricultural innovations were made, increasing the food supply and population. Classical Greek texts were translated from Arabic and Greek into Latin, stimulating scientific discussion in Western Europe.[165]

Inclassical antiquity,Greek and Roman taboos had meant that dissection was usually banned, but in the Middle Ages medical teachers and students at Bologna began to open human bodies, andMondino de Luzzi(c. 1275–1326) produced the first known anatomy textbook based on human dissection.[166][167]

As a result of thePax Mongolica,Europeans, such asMarco Polo,began to venture further and further east. The written accounts of Polo and his fellow travelers inspired other Western European maritime explorers to search for a direct sea route to Asia, ultimately leading to theAge of Discovery.[168]

Technological advances were also made, such as the early flight ofEilmer of Malmesbury(who had studied mathematics in 11th-century England),[169]and the metallurgical achievements of theCistercianblast furnaceatLaskill.[170][171]

Medieval universities

[edit]An intellectual revitalization of Western Europe started with the birth ofmedieval universitiesin the 12th century. These urban institutions grew from the informal scholarly activities of learnedfriarswho visitedmonasteries,consultedlibraries,and conversed with other fellow scholars.[172]A friar who became well-known would attract a following of disciples, giving rise to a brotherhood of scholars (orcollegiumin Latin). Acollegiummight travel to a town or request a monastery to host them. However, if the number of scholars within acollegiumgrew too large, they would opt to settle in a town instead.[172]As the number ofcollegiawithin a town grew, thecollegiamight request that their king grant them acharterthat would convert them into auniversitas.[172]Many universities were chartered during this period, with the first inBolognain 1088, followed byParisin 1150,Oxfordin 1167, andCambridgein 1231.[172]The granting of a charter meant that the medieval universities were partially sovereign and independent from local authorities.[172]Their independence allowed them to conduct themselves and judge their own members based on their own rules. Furthermore, as initially religious institutions, their faculties and students were protected from capital punishment (e.g.,gallows).[172]Such independence was a matter of custom, which could, in principle, be revoked by their respective rulers if they felt threatened. Discussions of various subjects or claims at these medieval institutions, no matter how controversial, were done in a formalized way so as to declare such discussions as being within the bounds of a university and therefore protected by the privileges of that institution's sovereignty.[172]A claim could be described asex cathedra(literally "from the chair", used within the context of teaching) orex hypothesi(by hypothesis). This meant that the discussions were presented as purely an intellectual exercise that did not require those involved to commit themselves to the truth of a claim or to proselytize. Modern academic concepts and practices such asacademic freedomor freedom of inquiry are remnants of these medieval privileges that were tolerated in the past.[172]

The curriculum of these medieval institutions centered on theseven liberal arts,which were aimed at providing beginning students with the skills for reasoning and scholarly language.[172]Students would begin their studies starting with the first three liberal arts orTrivium(grammar, rhetoric, and logic) followed by the next four liberal arts orQuadrivium(arithmetic, geometry, astronomy, and music).[172][142]Those who completed these requirements and received theirbaccalaureate(orBachelor of Arts) had the option to join the higher faculty (law, medicine, or theology), which would confer anLLDfor a lawyer, anMDfor a physician, orThDfor a theologian.[172]Students who chose to remain in the lower faculty (arts) could work towards aMagister(orMaster's) degree and would study three philosophies: metaphysics, ethics, and natural philosophy.[172]Latin translationsof Aristotle's works such asDe Anima(On the Soul) and the commentaries on them were required readings. As time passed, the lower faculty was allowed to confer its own doctoral degree called thePhD.[172]Many of the Masters were drawn to encyclopedias and had used them as textbooks. But these scholars yearned for the complete original texts of the Ancient Greek philosophers, mathematicians, and physicians such asAristotle,Euclid,andGalen,which were not available to them at the time. These Ancient Greek texts were to be found in the Byzantine Empire and the Islamic World.[172]

Translations of Greek and Arabic sources

[edit]Contact with the Byzantine Empire,[149]and with the Islamic world during theReconquistaand theCrusades,allowed Latin Europe access to scientificGreekandArabictexts, including the works ofAristotle,Ptolemy,Isidore of Miletus,John Philoponus,Jābir ibn Hayyān,al-Khwarizmi,Alhazen,Avicenna,andAverroes.European scholars had access to the translation programs ofRaymond of Toledo,who sponsored the 12th centuryToledo School of Translatorsfrom Arabic to Latin. Later translators likeMichael Scotuswould learn Arabic in order to study these texts directly. The European universities aided materially in thetranslation and propagation of these textsand started a new infrastructure which was needed for scientific communities. In fact, European university put many works about the natural world and the study of nature at the center of its curriculum,[173]with the result that the "medieval university laid far greater emphasis on science than does its modern counterpart and descendent."[174]

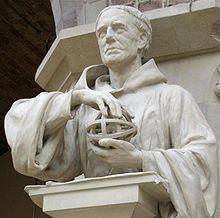

At the beginning of the 13th century, there were reasonably accurate Latin translations of the main works of almost all the intellectually crucial ancient authors, allowing a sound transfer of scientific ideas via both the universities and the monasteries. By then, the natural philosophy in these texts began to be extended byscholasticssuch asRobert Grosseteste,Roger Bacon,Albertus MagnusandDuns Scotus.Precursors of the modern scientific method, influenced by earlier contributions of the Islamic world, can be seen already in Grosseteste's emphasis on mathematics as a way to understand nature, and in the empirical approach admired by Bacon, particularly in hisOpus Majus.Pierre Duhem's thesis is thatStephen Tempier– the Bishop of Paris –Condemnation of 1277led to the study of medieval science as a serious discipline, "but no one in the field any longer endorses his view that modern science started in 1277".[175]However, many scholars agree with Duhem's view that the mid-late Middle Ages saw important scientific developments.[176][177][178]

Medieval science

[edit]The first half of the 14th century saw much important scientific work, largely within the framework ofscholasticcommentaries on Aristotle's scientific writings.[179]William of Ockhamemphasized the principle ofparsimony:natural philosophers should not postulate unnecessary entities, so that motion is not a distinct thing but is only the moving object[180]and an intermediary "sensible species" is not needed to transmit an image of an object to the eye.[181]Scholars such asJean BuridanandNicole Oresmestarted to reinterpret elements of Aristotle's mechanics. In particular, Buridan developed the theory that impetus was the cause of the motion of projectiles, which was a first step towards the modern concept ofinertia.[182]TheOxford Calculatorsbegan to mathematically analyze thekinematicsof motion, making this analysis without considering the causes of motion.[183]

In 1348, theBlack Deathand other disasters sealed a sudden end to philosophic and scientific development. Yet, the rediscovery of ancient texts was stimulated by theFall of Constantinoplein 1453, when many Byzantine scholars sought refuge in the West. Meanwhile, the introduction of printing was to have great effect on European society. The facilitated dissemination of the printed word democratized learning and allowed ideas such asalgebrato propagate more rapidly. These developments paved the way for theScientific Revolution,where scientific inquiry, halted at the start of the Black Death, resumed.[184][185]

Renaissance

[edit]Revival of learning

[edit]The renewal of learning in Europe began with 12th centuryScholasticism.TheNorthern Renaissanceshowed a decisive shift in focus from Aristotelian natural philosophy to chemistry and the biological sciences (botany, anatomy, and medicine).[186]Thus modern science in Europe was resumed in a period of great upheaval: the ProtestantReformationandCatholicCounter-Reformation;the discovery of the Americas byChristopher Columbus;theFall of Constantinople;but also the re-discovery of Aristotle during the Scholastic period presaged large social and political changes. Thus, a suitable environment was created in which it became possible to question scientific doctrine, in much the same way thatMartin LutherandJohn Calvinquestioned religious doctrine. The works of Ptolemy (astronomy) and Galen (medicine) were found not always to match everyday observations. Work byVesaliuson human cadavers found problems with the Galenic view of anatomy.[187]

The discovery ofCristallocontributed to the advancement of science in the period as well with its appearance out of Venice around 1450. The new glass allowed for better spectacles and eventually to the inventions of thetelescopeandmicroscope.

Theophrastus' work on rocks,Peri lithōn,remained authoritative for millennia: its interpretation of fossils was not overturned until after the Scientific Revolution.

During theItalian Renaissance,Niccolò Machiavelliestablished the emphasis of modern political science on directempiricalobservationof politicalinstitutionsand actors. Later, the expansion of the scientific paradigm during theEnlightenmentfurther pushed the study of politics beyond normative determinations.[188]In particular, the study ofstatistics,to study the subjects of thestate,has been applied topollingandvoting.

In archaeology, the 15th and 16th centuries saw the rise ofantiquariansinRenaissance Europewho were interested in the collection of artifacts.

Scientific Revolution and birth of New Science

[edit]

Theearly modern periodis seen as a flowering of the European Renaissance. There was a willingness to question previously held truths and search for new answers. This resulted in a period of major scientific advancements, now known as theScientific Revolution,which led to the emergence of a New Science that was moremechanisticin its worldview, more integrated with mathematics, and more reliable and open as its knowledge was based on a newly definedscientific method.[12][15][16][189]The Scientific Revolution is a convenient boundary between ancient thought and classical physics, and is traditionally held to have begun in 1543, when the booksDe humani corporis fabrica(On the Workings of the Human Body) byAndreas Vesalius,and alsoDe Revolutionibus,by the astronomerNicolaus Copernicus,were first printed. The period culminated with the publication of thePhilosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematicain 1687 byIsaac Newton,representative of the unprecedented growth ofscientific publicationsthroughout Europe.

Other significant scientific advances were made during this time byGalileo Galilei,Johannes Kepler,Edmond Halley,William Harvey,Pierre Fermat,Robert Hooke,Christiaan Huygens,Tycho Brahe,Marin Mersenne,Gottfried Leibniz,Isaac Newton,andBlaise Pascal.[190]In philosophy, major contributions were made byFrancis Bacon,SirThomas Browne,René Descartes,Baruch Spinoza,Pierre Gassendi,Robert Boyle,andThomas Hobbes.[190]Christiaan Huygensderived the centripetal and centrifugal forces and was the first to transfer mathematical inquiry to describe unobservable physical phenomena.William Gilbertdid some of the earliest experiments with electricity and magnetism, establishing that the Earth itself is magnetic.

Heliocentrism

[edit]

Theheliocentricastronomical model of the universe was refined byNicolaus Copernicus.Copernicus proposed the idea that the Earth and all heavenly spheres, containing the planets and other objects in the cosmos, rotated around the Sun.[191]His heliocentric model also proposed that all stars were fixed and did not rotate on an axis, nor in any motion at all.[192]His theory proposed the yearly rotation of the Earth and the other heavenly spheres around the Sun and was able to calculate the distances of planets using deferents and epicycles. Although these calculations were not completely accurate, Copernicus was able to understand the distance order of each heavenly sphere. The Copernican heliocentric system was a revival of the hypotheses ofAristarchus of SamosandSeleucus of Seleucia.[193]Aristarchus of Samos did propose that the Earth rotated around the Sun but did not mention anything about the other heavenly spheres' order, motion, or rotation.[194]Seleucus of Seleucia also proposed the rotation of the Earth around the Sun but did not mention anything about the other heavenly spheres. In addition, Seleucus of Seleucia understood that the Moon rotated around the Earth and could be used to explain the tides of the oceans, thus further proving his understanding of the heliocentric idea.[195]

Age of Enlightenment

[edit]

Continuation of Scientific Revolution

[edit]The Scientific Revolution continued into theAge of Enlightenment,which accelerated the development of modern science.

Planets and orbits

[edit]The heliocentric model revived byNicolaus Copernicuswas followed by the model of planetary motion given byJohannes Keplerin the early 17th century, which proposed that the planets followellipticalorbits, with the Sun at one focus of the ellipse. InAstronomia Nova(A New Astronomy), the first two of thelaws of planetary motionwere shown by the analysis of the orbit of Mars. Kepler introduced the revolutionary concept of planetary orbit. Because of his work astronomical phenomena came to be seen as being governed by physical laws.[199]

Emergence of chemistry

[edit]A decisive moment came when "chemistry" was distinguished fromalchemybyRobert Boylein his workThe Sceptical Chymist,in 1661; although the alchemical tradition continued for some time after his work. Other important steps included the gravimetric experimental practices of medical chemists likeWilliam Cullen,Joseph Black,Torbern BergmanandPierre Macquerand through the work ofAntoine Lavoisier( "father of modern chemistry") onoxygenand the law ofconservation of mass,which refutedphlogiston theory.Modern chemistry emerged from the sixteenth through the eighteenth centuries through the material practices and theories promoted by alchemy, medicine, manufacturing and mining.[200][201][202]

Calculus and Newtonian mechanics

[edit]In 1687, Isaac Newton published thePrincipia Mathematica,detailing two comprehensive and successful physical theories:Newton's laws of motion,which led to classical mechanics; andNewton's law of universal gravitation,which describes the fundamental force of gravity.

Circulatory system

[edit]William HarveypublishedDe Motu Cordisin 1628, which revealed his conclusions based on his extensive studies ofvertebratecirculatory systems.[190]He identified the central role of theheart,arteries,andveinsin producing blood movement in a circuit, and failed to find any confirmation ofGalen's pre-existing notions of heating and cooling functions.[203]The history of early modern biology and medicine is often told through the search for the seat of the soul.[204]Galen in his descriptions of his foundational work in medicine presents the distinctions between arteries, veins, and nerves using the vocabulary of the soul.[205]

Scientific societies and journals

[edit]A critical innovation was the creation of permanent scientific societies and their scholarly journals, which dramatically sped the diffusion of new ideas. Typical was the founding of theRoyal Societyin London in 1660 and its journal in 1665 thePhilosophical Transaction of the Royal Society,the first scientific journal in English.[206]1665 also saw the first journal in French, theJournal dessçavans.Science drawing on the works[207]ofNewton,Descartes,PascalandLeibniz,science was on a path to modernmathematics,physicsandtechnologyby the time of the generation ofBenjamin Franklin(1706–1790),Leonhard Euler(1707–1783),Mikhail Lomonosov(1711–1765) andJean le Rond d'Alembert(1717–1783).Denis Diderot'sEncyclopédie,published between 1751 and 1772 brought this new understanding to a wider audience. The impact of this process was not limited to science and technology, but affectedphilosophy(Immanuel Kant,David Hume),religion(the increasingly significant impact ofscience upon religion), and society and politics in general (Adam Smith,Voltaire).

Developments in geology

[edit]Geology did not undergo systematic restructuring during theScientific Revolutionbut instead existed as a cloud of isolated, disconnected ideas about rocks, minerals, and landforms long before it became a coherent science.Robert Hookeformulated a theory of earthquakes, andNicholas Stenodeveloped the theory ofsuperpositionand argued thatfossilswere the remains of once-living creatures. Beginning withThomas Burnet'sSacred Theory of the Earthin 1681, natural philosophers began to explore the idea that the Earth had changed over time. Burnet and his contemporaries interpreted Earth's past in terms of events described in the Bible, but their work laid the intellectual foundations for secular interpretations of Earth history.

Post-Scientific Revolution

[edit]Bioelectricity

[edit]During the late 18th century, researchers such asHugh Williamson[208]andJohn Walshexperimented on the effects of electricity on the human body. Further studies byLuigi GalvaniandAlessandro Voltaestablished the electrical nature of what Volta calledgalvanism.[209][210]

Developments in geology

[edit]

Modern geology, like modern chemistry, gradually evolved during the 18th and early 19th centuries.Benoît de Mailletand theComte de Buffonsaw the Earth as much older than the 6,000 years envisioned by biblical scholars.Jean-Étienne GuettardandNicolas Desmaresthiked central France and recorded their observations on some of the first geological maps. Aided by chemical experimentation, naturalists such as Scotland'sJohn Walker,[211]Sweden's Torbern Bergman, and Germany'sAbraham Wernercreated comprehensive classification systems for rocks and minerals—a collective achievement that transformed geology into a cutting edge field by the end of the eighteenth century. These early geologists also proposed a generalized interpretations of Earth history that ledJames Hutton,Georges CuvierandAlexandre Brongniart,following in the steps ofSteno,to argue that layers of rock could be dated by the fossils they contained: a principle first applied to the geology of the Paris Basin. The use ofindex fossilsbecame a powerful tool for making geological maps, because it allowed geologists to correlate the rocks in one locality with those of similar age in other, distant localities.

Birth of modern economics

[edit]

The basis forclassical economicsformsAdam Smith'sAn Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations,published in 1776. Smith criticizedmercantilism,advocating a system of free trade withdivision of labour.He postulated an "invisible hand"that regulated economic systems made up of actors guided only by self-interest. The" invisible hand "mentioned in a lost page in the middle of a chapter in the middle of the"Wealth of Nations",1776, advances as Smith's central message.

Social science

[edit]Anthropology can best be understood as an outgrowth of the Age of Enlightenment. It was during this period that Europeans attempted systematically to study human behavior. Traditions of jurisprudence, history, philology and sociology developed during this time and informed the development of the social sciences of which anthropology was a part.

19th century

[edit]The 19th century saw the birth of science as a profession.William Whewellhad coined the termscientistin 1833,[212]which soon replaced the older termnatural philosopher.

Developments in physics

[edit]

In physics, the behavior of electricity and magnetism was studied byGiovanni Aldini,Alessandro Volta,Michael Faraday,Georg Ohm,and others. The experiments, theories and discoveries ofMichael Faraday,Andre-Marie Ampere,James Clerk Maxwell,and their contemporaries led to the unification of the two phenomena into a single theory ofelectromagnetismas described byMaxwell's equations.Thermodynamicsled to an understanding of heat and the notion of energy being defined.

Discovery of Neptune

[edit]In astronomy, the planet Neptune was discovered. Advances in astronomy and in optical systems in the 19th century resulted in the first observation of anasteroid(1 Ceres) in 1801, and the discovery ofNeptunein 1846.

Developments in mathematics

[edit]In mathematics, the notion of complex numbers finally matured and led to a subsequent analytical theory; they also began the use ofhypercomplex numbers.Karl Weierstrassand others carried out thearithmetization of analysisfor functions ofrealandcomplex variables.It also saw rise tonew progress in geometrybeyond those classical theories of Euclid, after a period of nearly two thousand years. The mathematical science of logic likewise had revolutionary breakthroughs after a similarly long period of stagnation. But the most important step in science at this time were the ideas formulated by the creators of electrical science. Their work changed the face of physics and made possible for new technology to come about such as electric power, electrical telegraphy, the telephone, and radio.

Developments in chemistry

[edit]

In chemistry,Dmitri Mendeleev,following theatomic theoryofJohn Dalton,created the firstperiodic tableofelements.Other highlights include the discoveries unveiling the nature of atomic structure and matter, simultaneously with chemistry – and of new kinds of radiation. The theory that all matter is made of atoms, which are the smallest constituents of matter that cannot be broken down without losing the basic chemical and physical properties of that matter, was provided byJohn Daltonin 1803, although the question took a hundred years to settle as proven. Dalton also formulated the law of mass relationships. In 1869,Dmitri Mendeleevcomposed hisperiodic tableof elements on the basis of Dalton's discoveries. The synthesis ofureabyFriedrich Wöhleropened a new research field,organic chemistry,and by the end of the 19th century, scientists were able to synthesize hundreds of organic compounds. The later part of the 19th century saw the exploitation of the Earth's petrochemicals, after the exhaustion of the oil supply fromwhaling.By the 20th century, systematic production of refined materials provided a ready supply of products which provided not only energy, but also synthetic materials for clothing, medicine, and everyday disposable resources. Application of the techniques of organic chemistry to living organisms resulted inphysiological chemistry,the precursor tobiochemistry.[213]

Age of the Earth