Islam in Japan

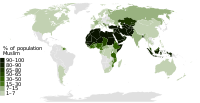

| Islam by country |

|---|

|

|

|

The history ofIslam inJapanis relatively brief in relation to thereligion's longstanding presence in other nearby countries, and forms a minority of its historical and current population. Islam is one of the smallest minority faiths in Japan, representing around 0.18% of the total population as of 2019.[1]Despite a small initial population base, immigration fromMuslim majoritycountries has made Islam one of the fastest growing religions in the country in terms of percentage increase, with its followers growing by approximately 110%, from 110,000 in 2010 to 230,000 at the end of 2019, out of the total population of Japan of around 126 million.[2][3][4]

While there were isolated occasions of Muslim presence in Japan before the 19th century, today, approximately 95% of Muslims in Japan are of foreign origin, with the rest being native Japanese converts.[5][6]

History

[edit]Early history

[edit]There are isolated records of contact between Islam and Japan before the opening of the country in 1853,[7]possibly as early as the 1700s; some Muslims did arrive in earlier centuries, although these were isolated incidents. Some elements ofIslamic philosophywere also distilled as far as back as theHeian periodthroughChineseandSoutheast Asiansources.[5]

Medieval and early modern records

[edit]

The earliest Muslim records of Japan can be found in the works of the Persian cartographerIbn Khordadbeh,who has been understood byMichael Jan de Goejeto mention Japan as the "lands ofWaqwaq"twice:"East of China are the lands of Waqwaq, which are so rich in gold that the inhabitants make the chains for their dogs and the collars for their monkeys of this metal. They manufacture tunics woven with gold. Excellent ebony wood is found there." And: "Gold and ebony are exported from Waqwaq."[8]Mahmud Kashgari's 11th century atlas indicates the land routes of theSilk RoadandJapanin the map's easternmost extent.

The first recorded Muslim in history to go to Japan was Sadr ud-Din ( rải đều lỗ đinh pronounced as Sādōulǔdīng in Chinese and Sadorotei in Japanese, also wrongly transcribed as đều lỗ đinh Dūlǔdīng and triệt đều lỗ đinh Chèdōulǔdīng by the Japanese), sent byYuan Chinain 1275 as a diplomatic delegation ordering the Japanese to submit to the Yuan emperor between the twoMongol invasions of Japan.He was beheaded by the Japanese. A Buddhist monk criticised the executions of the envoys.[9][10]

The Persian historianRashid al-Din Hamadanimentioned Japan twice in his historical workJami' al-tawarikhas Jimingu and described it having many cities and mines.

During that period there was contact between theHui,generalLan Yuof theMing dynastyand theswordsmiths of Japan.According to Chinese sources, Lan Yu owned 10,000Katana,Hongwu Emperor was displeased with the general's links withKyotoand more than 15,000 people were implicated for alleged treason and executed.[11][12]Lan Yu's ethnicity is disputed with some Hui claiming he was Hui but his biography in official Ming records do not mention him being Hui.

In the 13th century, amanuscriptwritten by Persians fromQuanzhouin China for the Japanese monkKeiseiwas brought back to Japan.[13]

Early European accounts of Muslims and their contacts with Japan were maintained byPortuguesesailors who mention a passenger aboard their ship, anArabwho had preachedIslamto the people of Japan. He had sailed to the islands inMalaccain 1555.[14][15]

In the 17th century,Iranian merchants from Thailandarrived toNagasakiduring theEdo period.[13]The IranianShaykh Ahmadfought and defeated Japanese merchants who attempted a coup against the Thai king in 1611.[16]In the 17th century textSafine-ye Solaymani,Shiawriter Mohammad Ibrahim described Japan and its culture, economy, recent political upheavals and their relationship with foreign merchants.[17]

Modern records

[edit]In the late 1870s, thebiography of Muhammadwas translated into Japanese. This helped Islam spread and reach the Japanese people, but only as a part of the history of cultures.[citation needed]

Another important contact was made in 1890 whenSultanandCaliphAbdul Hamid IIof theOttoman Empiredispatched a naval vessel to Japan for the purpose of saluting the visit of JapanesePrince Komatsu Akihitoto the capital ofConstantinopleseveral years earlier. This frigate was called theErtugrul,and was destroyed in a storm on the way back along the coast of Wakayama Prefecture on September 16, 1890. TheKushimoto Turkish Memorial and Museumare dedicated in honor of the drowned diplomats and sailors.[citation needed]

In 1891, an Ottoman crew who were shipwrecked on the Japanese coast the previous year were assisted in their return to Constantinople by the Imperial Japanese navy. Shotaro Noda, a journalist who accompanied them, became the earliest known Japanese convert during his stay in the Ottoman capital.[5]

Early 20th century

[edit]

In the wake of theOctober Revolution,several hundredTatarMuslimrefugees fromCentral AsiaandRussiawere given asylum in Japan, settling in several main cities and formed small communities. Some Japanese converted to Islam through contact with these Muslims. Historian Caeser E. Farah documented that in 1909 the Russian-bornAyaz İshakiand writerAbdurreshid Ibrahim(1857–1944), were the first Muslims who successfully converted the first ethnic Japanese, when Kotaro Yamaoka converted in 1909 in Bombay after contacting Ibrahim and took the name Omar Yamaoka.[18]Yamaoka became the first Japanese to go on theHajj.Yamaoka and Ibrahim were traveling with the support of nationalistic Japanese groups likeBlack Dragon Society(Kokuryūkai). Yamaoka in fact had been with theintelligence serviceinManchuriasince theRusso-Japanese war.His official reason for traveling was to seek theOttoman SultanandCaliph's approval for building a mosque in Tokyo. This approval was granted in 1910. TheTokyo Mosque,was finally completed on 12 May 1938, with generous financial support from thezaibatsu.Its first imams were Abdul-Rashid Ibrahim and Abdülhay Kurban Ali (Muhammed-Gabdulkhay Kurbangaliev) (1889–1972). However, Japan's first mosque, theKobe Mosquewas built in 1935, with the support of the Turko-Tatar community of traders there.[19]On 12 May 1938, a mosque was dedicated in Tokyo.[20]Another early Japanese convert was Bunpachiro Ariga, who about the same time as Yamaoka went to India for trading purposes and converted to Islam under the influence of local Muslims there, and subsequently took the name Ahmed Ariga. Yamada Toajiro was for almost 20 years from 1892 the only resident Japanese trader in Constantinople.[21]During this time he served unofficially asconsul.He converted to Islam, and took the name Abdul Khalil, and made a pilgrimage to Mecca on his way home.

Japanese nationalists and Islam

[edit]

In the lateMeiji period,close relations were forged between Japanese military elites with anAsianistagenda and Muslims to find a common cause with those suffering under the yoke of Western hegemony.[22]In 1906, widespread propaganda campaigns were aimed at Muslim nations with journals reporting that a Congress of religions was to be held in Japan where the Japanese would seriously consider adopting Islam as the national religion and that the Emperor was at the point of becoming a Muslim.[23]

Nationalistic organizations like the Ajia Gikai were instrumental in petitioning the Japanese government on matters such as officially recognizing Islam, along withShintoism,ChristianityandBuddhismas a religion in Japan, and in providing funding and training to Muslim resistance movements in Southeast Asia, such as the Hizbullah, a resistance group funded by Japan in the Dutch Indies. The Greater Japan Muslim League(Đại Nhật Bản hồi giáo hiệp hội,Dai Nihon Kaikyō Kyōkai)founded in 1930, was the first official Islamic organisation in Japan. It had the support of imperialistic circles duringWorld War II,and caused an "Islamic Studies Book".[24]During this period, over 100 books and journals on Islam were published in Japan. While these organizations had their primary aim in intellectually equipping Japan's forces and intellectuals with better knowledge and understanding of the Islamic world, dismissing them as mere attempts to further Japan's aims for a "Greater Asia"does not reflect the nature of depth of these studies. Japanese and Muslim academia in their common aims of defeatingWestern colonialismhad been forging ties since the early twentieth century, and with the destruction of the last remaining Muslim power, the Ottoman Empire, the advent of hostilities inWorld War IIand the possibility of the same fate awaiting Japan, these academic and political exchanges and the alliances created reached a head. Therefore, they were extremely active in forging links with academia and Muslim leaders and revolutionaries, many of whom were invited to Japan.

Shūmei Ōkawa,by far the highest-placed and most prominent figure in both Japanese government and academia in the matter of Japanese-Islamic exchange and studies, managed to complete his translation of theQur'anin prison, while being prosecuted as an allegedclass-A war criminalby the victorious Allied forces for being an 'organ of propaganda'.[25]Charges were dropped due to the results of psychiatric tests.[26]

Post–World War II

[edit]The Japanese invasion of China and South East Asian regions during the Second World War brought the Japanese in contact with Muslims. Those who converted to Islam through them returned to Japan and established in 1953 the first Japanese Muslim organisation, the "Japan Muslim Association", which was officially granted recognition as a religious organization by the Japanese government in June 1968.[19]The second president of the association wasRyoichi Mitaalso known as Umar Mita, who was typical of the old generation, learning Islam in the territories occupied by theJapanese Empire.He was working for theSouth Manchuria Railway,which virtually controlled the Japanese territory in the northeastern province of China at that time. Through his contacts with Chinese Muslims, he formally became a Muslim in 1941 atBeijingand changed his name to Umar Mita.[27]Then in 1945 he returned to Japan after the war. He made theHajjin 1958, the first Japanese in the post-war period to do so. He also made a Japanese translation of the Qur'an from a Muslim perspective for the first time.Al Jazeeraalso made a documentary regarding Islam and Japan called "Road to Hajj – Japan".[28]

The economic boom in the country in the 1980s saw an influx of immigrants to Japan, including from majority Muslim nations. These immigrants and their descendants form the majority of Muslims in the country. Today, there are Muslim student associations at some Japanese universities.[19]In 2016, Japan accepted 0.3% ofrefugeeapplicants, many of whom are Muslims.[29]

Demographics

[edit]In 1941, one of the chief sponsors of the Tokyo Mosque asserted that the number of Muslims in Japan numbered 600, with just three or four being native Japanese.[20]Some sources state that in 1982 the Muslims numbered 30,000 (half were natives).[18]Of the ethnically Japanese Muslims, the majority are thought to be ethnic Japanese women who married immigrant Muslims who arrived during the economic boom of the 1980s, but there are also a small number of intellectuals, including university professors, who have converted.[30][19]Most estimates of the Muslim population in the 2000s give a range around 100,000 total.[18][19][31]Islam remains a minority religion in Japan. Conversion is more prominent among young ethnic Japanese married women, as claimed byThe Modern Religionas early as the 1990s.[30]

The true size of the current Muslim population in Japan remains a matter of speculation. Japanese scholars such as Hiroshi Kojima of the National Institute of Population and Social Security Research and Keiko Sakurai of Waseda University suggest a Muslim population of around 70,000 in 2007, of which perhaps 90% are resident foreigners and about 10% native Japanese.[32][19]Of the immigrant communities, in order of population size, are Indonesians, Indians, Pakistanis and Bangladeshis.[19]The Pew Research Center estimated that there were 185,000 Muslims in Japan in 2010.[33]For 2019 it was estimated that the numbers rose to 230,000, due to the more friendly policies towards immigration, the Japanese converts being estimated at 50,000, and Japan now has more than 110 mosques compared to 24 in 2001.[34]As of 2020, nearly half of the Muslims in Japan were Indonesians, Filipinos, and Malaysians.[35]Another 2019 estimate places the total number at 200,000, with a ratio of 90:10 for those of foreign origin to native Japanese converts.[5]

Population by prefecture

[edit]The percentages of Muslim populations of each prefecture from 2020.[36]

Table

[edit]| Prefectures | Total Population | Muslim Population | Muslim percentage of total population |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aichi | 7,542,415 | 21,920 | 0.3 |

| Akita | 959,502 | 331 | < 0.1 |

| Aomori | 1,237,984 | 560 | < 0.1 |

| Chiba | 6,284,480 | 15,575 | 0.2 |

| Ehime | 1,344,841 | 1,247 | < 0.1 |

| Fukui | 766,863 | 747 | < 0.1 |

| Fukuoka | 5,135,214 | 5,022 | < 0.1 |

| Fukushima | 1,833,152 | 1,449 | < 0.1 |

| Gifu | 1,978,742 | 3,740 | 0.2 |

| Gunma | 1,939,110 | 8,809 | 0.5 |

| Hiroshima | 2,799,702 | 4,858 | 0.2 |

| Hokkaidō | 5,224,614 | 3,262 | < 0.1 |

| Hyōgo | 5,465,002 | 5,244 | < 0.1 |

| Ibaraki | 2,867,009 | 13,743 | 0.5 |

| Ishikawa | 1,132,852 | 1,661 | 0.1 |

| Iwate | 1,210,534 | 679 | < 0.1 |

| Kagawa | 950,244 | 2,034 | 0.2 |

| Kagoshima | 1,588,256 | 1,280 | < 0.1 |

| Kanagawa | 9,237,337 | 16,283 | 0.2 |

| Kōchi | 691,527 | 632 | < 0.1 |

| Kumamoto | 1,738,301 | 1,704 | < 0.1 |

| Kyōto | 2,578,087 | 3,359 | 0.1 |

| Mie | 1,770,254 | 4,160 | 0.2 |

| Miyagi | 2,301,996 | 3,179 | 0.1 |

| Miyazaki | 1,069,576 | 1,471 | 0.1 |

| Nagano | 2,048,011 | 3,127 | 0.2 |

| Nagasaki | 1,312,317 | 786 | 0.1 |

| Nara | 1,324,473 | 986 | 0.1 |

| Nīgata | 2,201,272 | 2,004 | 0.1 |

| Ōita | 1,123,852 | 2,154 | 0.2 |

| Okayama | 1,888,432 | 3,152 | 0.2 |

| Okinawa | 1,467,480 | 2,275 | 0.2 |

| Ōsaka | 8,837,685 | 10,660 | 0.1 |

| Saga | 811,442 | 1,221 | 0.2 |

| Saitama | 7,344,765 | 22,703 | 0.3 |

| Shiga | 1,413,610 | 2,332 | 0.2 |

| Shimane | 671,126 | 513 | 0.1 |

| Shizuoka | 3,633,202 | 7,721 | 0.2 |

| Tochigi | 1,933,146 | 6,227 | 0.3 |

| Tokushima | 719,559 | 918 | 0.1 |

| Tokyo | 14,047,594 | 30,819 | 0.2 |

| Tottori | 553,407 | 451 | 0.1 |

| Toyama | 1,034,814 | 2,645 | 0.3 |

| Wakayama | 922,584 | 485 | 0.1 |

| Yamagata | 1,068,027 | 625 | 0.1 |

| Yamaguchi | 1,342,059 | 1,337 | 0.1 |

| Yamanashi | 809,974 | 851 | 0.1 |

| Japan | 126,156,425 | 226,941 | 0.2 |

Mosques

[edit]-

Kobe Mosque,Japan's first mosque, built in Indo-Islamic style in 1935 byJan Josef Švagr

-

Tokyo Mosque,Japan's largest mosque

Japan's first mosque was theKobe Muslim Mosque,established in 1935. According to japanfocus.org, as of 2009[update]there were 30 to 40 single-story mosques in Japan, The largest of which is theTokyo Mosque,plus another 100 or more apartment rooms set aside for prayers in the absence of more suitable facilities. 90% of these mosques use the 2nd floor for religious activities and the first floor as ahalalshop (imported food; mainly from Indonesia and Malaysia), due to financial problems, as membership is too low to cover the expenses. Most of these mosques have only a capacity of 30 to 50 people.[37]In 2016, the first ever mosque tailored for native Japanese worshipers (as opposed to services in foreign languages) was opened.[5]As of 2023, there is oneAhmadimosque in Japan,The Japan Mosque.It was established in 2015 byMirza Masroor Ahmad,the mosque has a capacity of 500 worshippers, the largest of any mosque in Japan.[38]

Notable Muslims

[edit]- Antonio Inoki

- Dewi Sukarno

- Kōhan Kawauchi

- Masatoşi Gündüz İkeda

- Mitsutarō Yamaoka

- Ryoichi Mita

- Shotaro Noda

- Sultan Nour

- Tani Yutaka

See also

[edit]- Religion in Japan

- Arabs in Japan

- Uzbeks in Japan

- Iranians in Japan

- Persian manuscript in Japan

- Japan Muslim Association

- List of Major Mosques in Japan

- Ahmadiyya in Japan

Notes

[edit]- ^"The number of Muslims in Japan is growing fast".The Economist.

- ^"The number of Muslims in Japan is growing fast".The Economist.

- ^"National Profiles".

- ^"Ever growing Muslim community in the world and Japan".

- ^abcdeTakahashi (2021)."Islamophobia in Japan: A Country at a Crossroads".Islamophobia Studies Journal.6(2): 167–181.doi:10.13169/islastudj.6.2.0167.JSTOR10.13169/islastudj.6.2.0167.S2CID239198369.

- ^L, Aaron (2007-05-02)."Local Mosques and the Lives of Muslims in Japan".The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus.Archived fromthe originalon 2024-08-18.Retrieved2024-08-18.

- ^Obuse, Keiko."Islam in Japan".Oxford Bibliographies.Retrieved2021-09-22.

- ^Saudi Aramco World: The Seas of Sindbad,Paul Lunde

- ^Morris, James Harry (2018)."Some Reflections on the First Muslim Visitor to Japan".American Journal of Islam and Society.35(3).doi:10.35632/ajis.v35i3.150.

- ^Morris, James Harry (2020)."Christian-Muslim relations in 19th-century Japan".Christian-Muslim Relations. A Bibliographical History Volume 16 North America, South-East Asia, China, Japan, and Australasia (1800-1914).Brill. pp. 485–506.doi:10.1163/9789004429901_007.ISBN978-90-04-42990-1.S2CID241069441.

- ^( 26 năm hai tháng, Cẩm Y Vệ chỉ huy Tưởng hiến cáo ngọc mưu phản, hạ lại cúc tin. Ngục từ vân: “Ngọc cùng cảnh xuyên hầu tào chấn, hạc khánh hầu trương cánh, trục lô hầu Chu Thọ, đông hoàn bá gì vinh cập Lại Bộ thượng thư Chiêm huy, Hộ Bộ thị lang phó hữu văn chờ mưu vì biến, đem hầu đế ra tá điền khởi sự.” Ngục cụ, tộc tru chi. Liệt hầu dưới ngồi đảng di diệt giả không thể đếm. Tay chiếu bố cáo thiên hạ, điều liệt viên thư vì 《 nghịch thần lục 》. Đến chín tháng, nãi hạ chiếu rằng: “Lam tặc vì loạn, mưu tiết, tộc tru giả vạn 5000 người. Tự nay hồ đảng, lam đảng khái xá không hỏi.” Hồ gọi thừa tướng duy dung cũng. Thế là nguyên công tướng già lần lượt tẫn rồi. Phàm liệt danh 《 nghịch thần lục 》 giả, một công, mười ba hầu, nhị bá. Diệp thăng trước ngồi sự tru, hồ ngọc chờ chư tiểu hầu toàn đừng thấy. Này tào chấn, trương cánh, trương ôn, trần Hoàn, Chu Thọ, tào hưng sáu hầu, bám vào tả phương. )

- ^Others implicated in the Lan Yu Case include: Han Xun ( Hàn huân ), Marquis of Dongping ( Đông Bình hầu ); Cao Tai ( tào thái ), Marquis of Xuanning ( tuyên ninh hầu ); Cao Xing ( tào hưng ), Marquis of Huaiyuan ( hoài xa hầu ); Ye Sheng ( diệp thăng ), Marquis of Jingning ( tĩnh ninh hầu ); Cao Zhen ( tào chấn ), Marquis of Jingchuan ( cảnh xuyên hầu ); Zhang Wen ( trương ôn ), Marquis of Huining ( sẽ ninh hầu ); Chen Huan ( trần Hoàn ), Marquis of Puding ( phổ định hầu ); Zhang Yi ( trương cánh ), Marquis of Heqing ( hạc khánh hầu ); Zhu Shou ( Chu Thọ ), Marquis of Zhulu ( trục lô hầu ); Chahan ( sát hãn ), Marquis of Haixi ( hải tây hầu ); Sun Ke ( tôn khác ), Marquis of Quanning ( toàn ninh hầu ); He Rong ( gì vinh ), Count of Dongguan ( đông hoàn bá ); Sang Jing ( tang kính ), Count of Huixian ( huy trước bá )

- ^abToyoko, Morita (2012)."JAPAN iv. Iranians in Japan".Encyclopaedia Iranica.

- ^"Islam In Japan".Islamic Japanese.[permanent dead link]

- ^Asia in the Making of Europe, Volume I: The Century of Discovery.-Donald F. Lach- Google Books

- ^TOMB OF SHEIKH AHMAD QOMI - History of Ayutthaya

- ^Ibrahim, Muhammad (1972).The Ship of Sulaiman.Translated by O'Kane, John. Columbia University Press. pp. 188–197.ISBN9781135029852.

- ^abcE. Farah, Caesar (25 April 2003).Islam: Beliefs and Observations.Barron's Educational Series; 7th Revised edition.ISBN978-0-7641-2226-2.

- ^abcdefgPenn, Michael."Islam in Japan".Harvard Asia Quarterly.Archivedfrom the original on 2 February 2007.Retrieved28 December2008.

- ^abR&A No. 890 1943,p. 1

- ^His memoirs: Toruko Gakan, Tokyo 1911

- ^Japan's Global Claim to Asia and the World of Islam: Transnational Nationalism and World Power, 1900-1945. S Esenbel. The American Historical Review 109 (4), 1140-1170

- ^Bodde, Derk. “Japan and the Muslims of China.” Far Eastern Survey, vol. 15, no. 20, 1946, pp. 311–313., jstor.org/stable/3021860.

- ^Most of its produced literature is preserved in theWaseda University Library("Archived copy"(PDF).Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 2009-03-06.Retrieved2007-12-06.

{{cite web}}:CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)Catalogue) - ^"Okawa Shumei".Britannica. 20 July 1998.Retrieved6 March2017.

- ^Zhaoqi Cheng (2019).A History of War Crimes Trials in Post 1945 Asia-Pacific.Springer. p.76.ISBN978-981-13-6697-0.

- ^"Islamic Culture Forum 2, Haji Umar Mita".

- ^"Road to Hajj — Japan - 26 Nov 09 - Pt 1".YouTube. 26 November 2009.Archivedfrom the original on 2021-12-19.Retrieved2 May2010.

- ^Ekin, Annette."Lives in limbo: Why Japan accepts so few refugees".Al Jazeera.

- ^abY. Nakano, Lynne; Japan Times Newspaper (November 19, 1992)."Marriages lead women into Islam in Japan".Japan Times.Retrieved27 December2008.

- ^International Religious Freedom Report 2008 - Japan

- ^Yasunori, Kawakami; JapanFocus.org (May 30, 2007)."Local Mosques and the Lives of Muslims in Japan".JapanFocus.org.Retrieved27 December2008.

- ^"Table: Muslim Population by Country".Pew Research Center. 27 January 2011.Retrieved19 March2017.

- ^"The number of Muslims in Japan is growing fast".The Economist.7 January 2021.Retrieved9 January2021.

- ^Barber, B. Bryan (2020).Japan's Relations with Muslim Asia.Palgrave Macmillan. p. 227.

- ^"Nhật Bản の ムスリム dân cư 1990〜2020 năm RPMJ20 hào – trệ ngày ムスリム điều tra プロジェクト".imemgs.Retrieved2022-08-16.

- ^"JapanFocus".JapanFocus. Archived fromthe originalon February 19, 2009.Retrieved2 May2010.

- ^Penn, Michael (November 28, 2015)."Japan's newest and largest mosque opens its doors".Al Jazeera Media Network.RetrievedNovember 14,2023.

References

[edit]- Abu Bakr Morimoto,Islam in Japan: Its Past, Present and Future,Islamic Centre Japan, 1980

- Arabia,Vol. 5, No. 54. February 1986/Jamad al-Awal 1406

- Hiroshi Kojima, "Demographic Analysis of Muslims in Japan," The 13th KAMES and 5th AFMA International Symposium, Pusan, 2004

- Michael Penn, "Islam in Japan: Adversity and Diversity,"Harvard Asia Quarterly,Vol. 10, No. 1, Winter 2006

- Keiko Sakurai,Nihon no Musurimu Shakai(Japan's Muslim Society), Chikuma Shobo, 2003

- Esenbel, Selcuk;Japanese Interest in the Ottoman Empire;in: Edstrom, Bert; The Japanese and Europe: Images and Perceptions; Surrey 2000

- Esenbel, Selcuk; Inaba Chiharū;The Rising Sun and the Turkish Crescent;İstanbul 2003,ISBN978-975-518-196-7

- A fin-de-siecle Japanese Romantic in Istanbul: The life of Yamada Torajirō and his Turoko gakan;BullSOAS,Vol. LIX-2 (1996), S 237-52...

- Research and Analysis Branch (15 May 1943)."Japanese Infiltration Among the Muslims Throughout the World (R&A No. 890)"(PDF).Office of Strategic Services.U.S. Central Intelligence Agency Library. Archived fromthe original(PDF)on August 27, 2016.