Johannes Kepler

Johannes Kepler | |

|---|---|

Portrait byAugust Köhler,c. 1910,after 1627 original | |

| Born | 27 December 1571 Free Imperial City of Weil der Stadt,Holy Roman Empire |

| Died | 15 November 1630(aged 58) Free Imperial City of Regensburg,Holy Roman Empire |

| Education | Tübinger Stift,University of Tübingen(M.A., 1591)[1] |

| Known for | |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Astronomy,astrology,mathematics,natural philosophy |

| Doctoral advisor | Michael Maestlin |

| Signature | |

| Part of a series on |

| Classical mechanics |

|---|

| Part of a series on |

| Physical cosmology |

|---|

|

Johannes Kepler(/ˈkɛplər/;[2]German:[joˈhanəsˈkɛplɐ,-nɛs-];[3][4]27 December 1571 – 15 November 1630) was a Germanastronomer,mathematician,astrologer,natural philosopherand writer on music.[5]He is a key figure in the 17th-centuryScientific Revolution,best known for hislaws of planetary motion,and his booksAstronomia nova,Harmonice Mundi,andEpitome Astronomiae Copernicanae,influencing among othersIsaac Newton,providing one of the foundations for his theory ofuniversal gravitation.[6]The variety and impact of his work made Kepler one of the founders and fathers of modernastronomy,thescientific method,naturalandmodern science.[7][8][9]He has been described as the "father ofscience fiction"for his novelSomnium.[10][11]

Kepler was a mathematics teacher at aseminaryschool inGraz,where he became an associate ofPrince Hans Ulrich von Eggenberg.Later he became an assistant to the astronomerTycho BraheinPrague,and eventually the imperial mathematician toEmperor Rudolf IIand his two successorsMatthiasandFerdinand II.He also taught mathematics inLinz,and was an adviser toGeneral Wallenstein. Additionally, he did fundamental work in the field ofoptics,being named the father of modern optics,[12]in particular for hisAstronomiae pars optica.He also invented an improved version of therefracting telescope,the Keplerian telescope, which became the foundation of the modern refracting telescope,[13]while also improving on the telescope design byGalileo Galilei,[14]who mentioned Kepler's discoveries in his work.

Kepler lived in an era when there was no clear distinction betweenastronomyandastrology,[15]but there was a strong division between astronomy (a branch ofmathematicswithin theliberal arts) andphysics(a branch ofnatural philosophy).[16]Kepler also incorporated religious arguments and reasoning into his work, motivated by the religious conviction and belief that God had created the world according to an intelligible plan that is accessible through the natural light ofreason.[17]Kepler described his new astronomy as "celestial physics",[18]as "an excursion intoAristotle'sMetaphysics",[19]and as "a supplement to Aristotle'sOn the Heavens",[20]transforming the ancient tradition of physical cosmology by treating astronomy as part of a universal mathematical physics.[21]

Early life

[edit]Childhood (1571–1590)

[edit]

Kepler was born on 27 December 1571, in theFree Imperial CityofWeil der Stadt(now part of theStuttgart Regionin the German state ofBaden-Württemberg). His grandfather, Sebald Kepler, had been Lord Mayor of the city. By the time Johannes was born, the Kepler family fortune was in decline. His father, Heinrich Kepler, earned a precarious living as amercenary,and he left the family when Johannes was five years old. He was believed to have died in theEighty Years' Warin the Netherlands. His mother,Katharina Guldenmann,an innkeeper's daughter, was ahealerandherbalist.Johannes had six siblings, of which two brothers and one sister survived to adulthood. Born prematurely, he claimed to have been weak and sickly as a child. Nevertheless, he often impressed travelers at his grandfather's inn with his phenomenal mathematical faculty.[22]

He was introduced to astronomy at an early age and developed a strong passion for it that would span his entire life. At age six, he observed theGreat Comet of 1577,writing that he "was taken by [his] mother to a high place to look at it."[23]In 1580, at age nine, he observed another astronomical event, alunar eclipse,recording that he remembered being "called outdoors" to see it and that theMoon"appeared quite red".[23]However, childhoodsmallpoxleft him with weak vision and crippled hands, limiting his ability in the observational aspects of astronomy.[24]

In 1589, after moving through grammar school,Latin school,andseminary at Maulbronn,Kepler attendedTübinger Stiftat theUniversity of Tübingen.There, he studied philosophy under Vitus Müller[25]andtheologyunderJacob Heerbrand(a student ofPhilipp Melanchthonat Wittenberg), who also taughtMichael Maestlinwhile he was a student, until he became Chancellor at Tübingen in 1590.[26]He proved himself to be a superb mathematician and earned a reputation as a skillful astrologer, castinghoroscopesfor fellow students. Under the instruction of Michael Maestlin, Tübingen's professor of mathematics from 1583 to 1631,[26]he learned both thePtolemaic systemand theCopernican systemof planetary motion. He became aCopernicanat that time. In a student disputation, he defendedheliocentrismfrom both a theoretical and theological perspective, maintaining that theSunwas the principal source of motive power in the universe.[27]Despite his desire to become a minister in the Lutheran church, he was denied ordination because of beliefs contrary to theFormula of Concord.[28]Near the end of his studies, Kepler was recommended for a position as teacher of mathematics and astronomy at the Protestant school in Graz. He accepted the position in April 1594, at the age of 22.[29]

Graz (1594–1600)

[edit]Before concluding his studies at Tübingen, Kepler accepted an offer to teach mathematics as a replacement to Georg Stadius at the Protestant school in Graz (now in Styria, Austria).[30]During this period (1594–1600), he issued many official calendars and prognostications that enhanced his reputation as an astrologer. Although Kepler had mixed feelings about astrology and disparaged many customary practices of astrologers, he believed deeply in a connection between the cosmos and the individual. He eventually published some of the ideas he had entertained while a student in theMysterium Cosmographicum(1596), published a little over a year after his arrival at Graz.[31]

In December 1595, Kepler was introduced to Barbara Müller, a 23-year-old widow (twice over) with a young daughter, Regina Lorenz, and he began courting her. Müller, an heiress to the estates of her late husbands, was also the daughter of a successful mill owner. Her father Jobst initially opposed a marriage. Even though Kepler had inherited his grandfather's nobility, Kepler's poverty made him an unacceptable match. Jobst relented after Kepler completed work onMysterium,but the engagement nearly fell apart while Kepler was away tending to the details of publication. However, Protestant officials—who had helped set up the match—pressured the Müllers to honor their agreement. Barbara and Johannes were married on 27 April 1597.[32]

In the first years of their marriage, the Keplers had two children (Heinrich and Susanna), both of whom died in infancy. In 1602, they had a daughter (Susanna); in 1604, a son (Friedrich); and in 1607, another son (Ludwig).[33]

Other research

[edit]Following the publication ofMysteriumand with the blessing of the Graz school inspectors, Kepler began an ambitious program to extend and elaborate his work. He planned four additional books: one on the stationary aspects of the universe (the Sun and the fixed stars); one on the planets and their motions; one on the physical nature of planets and the formation of geographical features (focused especially on Earth); and one on the effects of the heavens on the Earth, to include atmospheric optics, meteorology, and astrology.[34]

He also sought the opinions of many of the astronomers to whom he had sentMysterium,among themReimarus Ursus(Nicolaus Reimers Bär)—the imperial mathematician toRudolf IIand a bitter rival ofTycho Brahe.Ursus did not reply directly, but republished Kepler's flattering letter to pursue his priority dispute over (what is now called) theTychonic systemwith Tycho. Despite this black mark, Tycho also began corresponding with Kepler, starting with a harsh but legitimate critique of Kepler's system; among a host of objections, Tycho took issue with the use of inaccurate numerical data taken from Copernicus. Through their letters, Tycho and Kepler discussed a broad range of astronomical problems, dwelling on lunar phenomena and Copernican theory (particularly its theological viability). But without the significantly more accurate data of Tycho's observatory, Kepler had no way to address many of these issues.[35]

Instead, he turned his attention tochronologyand "harmony," thenumerologicalrelationships among music,mathematicsand the physical world, and theirastrologicalconsequences. By assuming the Earth to possess a soul (a property he would later invoke to explain how the Sun causes the motion of planets), he established a speculative system connectingastrological aspectsand astronomical distances toweatherand other earthly phenomena. By 1599, however, he again felt his work limited by the inaccuracy of available data—just as growing religious tension was also threatening his continued employment in Graz. In December of that year, Tycho invited Kepler to visit him inPrague;on 1 January 1600 (before he even received the invitation), Kepler set off in the hopes that Tycho's patronage could solve his philosophical problems as well as his social and financial ones.[36]

Scientific career

[edit]Prague (1600–1612)

[edit]

On 4 February 1600, Kepler metTycho Braheand his assistantsFranz TengnagelandLongomontanusatBenátky nad Jizerou(35 km from Prague), the site where Tycho's new observatory was being constructed. Over the next two months, he stayed as a guest, analyzing some of Tycho's observations of Mars; Tycho guarded his data closely, but was impressed by Kepler's theoretical ideas and soon allowed him more access. Kepler planned to test his theory fromMysterium Cosmographicumbased on the Mars data, but he estimated that the work would take up to two years (since he was not allowed to simply copy the data for his own use). With the help ofJohannes Jessenius,Kepler attempted to negotiate a more formal employment arrangement with Tycho, but negotiations broke down in an angry argument and Kepler left for Prague on 6 April. Kepler and Tycho soon reconciled and eventually reached an agreement on salary and living arrangements, and in June, Kepler returned home to Graz to collect his family.[37]

Political and religious difficulties in Graz dashed his hopes of returning immediately to Brahe; in hopes of continuing his astronomical studies, Kepler sought an appointment as a mathematician toArchduke Ferdinand.To that end, Kepler composed an essay—dedicated to Ferdinand—in which he proposed a force-based theory of lunar motion: "In Terra inest virtus, quae Lunam ciet" ( "There is a force in the earth which causes the moon to move" ).[38]Though the essay did not earn him a place in Ferdinand's court, it did detail a new method for measuring lunar eclipses, which he applied during the 10 July eclipse in Graz. These observations formed the basis of his explorations of the laws of optics that would culminate inAstronomiae Pars Optica.[39]

On 2 August 1600, after refusing to convert to Catholicism, Kepler and his family were banished from Graz. Several months later, Kepler returned, now with the rest of his household, to Prague. Through most of 1601, he was supported directly by Tycho, who assigned him to analyzing planetary observations and writing a tract against Tycho's (by then deceased) rival, Ursus. In September, Tycho secured him a commission as a collaborator on the new project he had proposed to the emperor: theRudolphine Tablesthat should replace thePrutenic TablesofErasmus Reinhold.Two days after Tycho's unexpected death on 24 October 1601, Kepler was appointed his successor as the imperial mathematician with the responsibility to complete his unfinished work. The next 11 years as imperial mathematician would be the most productive of his life.[40]

Imperial Advisor

[edit]Kepler's primary obligation as imperial mathematician was to provide astrological advice to the emperor. Though Kepler took a dim view of the attempts of contemporary astrologers to precisely predict the future or divine specific events, he had been casting well-received detailed horoscopes for friends, family, and patrons since his time as a student in Tübingen. In addition to horoscopes for allies and foreign leaders, the emperor sought Kepler's advice in times of political trouble. Rudolf was actively interested in the work of many of his court scholars (including numerousalchemists) and kept up with Kepler's work in physical astronomy as well.[41]

Officially, the only acceptable religious doctrines in Prague were Catholic andUtraquist,but Kepler's position in the imperial court allowed him to practice his Lutheran faith unhindered. The emperor nominally provided an ample income for his family, but the difficulties of the over-extended imperial treasury meant that actually getting hold of enough money to meet financial obligations was a continual struggle. Partly because of financial troubles, his life at home with Barbara was unpleasant, marred with bickering and bouts of sickness. Court life, however, brought Kepler into contact with other prominent scholars (Johannes Matthäus Wackher von Wackhenfels,Jost Bürgi,David Fabricius,Martin Bachazek, and Johannes Brengger, among others) and astronomical work proceeded rapidly.[42]

Supernova of 1604

[edit]

In October 1604, a bright new evening star (SN 1604) appeared, but Kepler did not believe the rumors until he saw it himself.[43]Kepler began systematically observing the supernova. Astrologically, the end of 1603 marked the beginning of afiery trigon,the start of the about 800-year cycle ofgreat conjunctions;astrologers associated the two previous such periods with the rise ofCharlemagne(c. 800 years earlier) and the birth of Christ (c. 1600 years earlier), and thus expected events of great portent, especially regarding the emperor.[44]

It was in this context, as the imperial mathematician and astrologer to the emperor, that Kepler described the new star two years later in hisDe Stella Nova.In it, Kepler addressed the star's astronomical properties while taking a skeptical approach to the many astrological interpretations then circulating. He noted its fading luminosity, speculated about its origin, and used the lack of observed parallax to argue that it was in the sphere of fixed stars, further undermining the doctrine of the immutability of the heavens (the idea accepted since Aristotle that thecelestial sphereswere perfect and unchanging). The birth of a new star implied the variability of the heavens. Kepler also attached an appendix where he discussed the recent chronology work of the Polish historianLaurentius Suslyga;he calculated that, if Suslyga was correct that accepted timelines were four years behind, then theStar of Bethlehem—analogous to the present new star—would have coincided with the first great conjunction of the earlier 800-year cycle.[45]

Over the following years, Kepler attempted (unsuccessfully) to begin a collaboration with Italian astronomerGiovanni Antonio Magini,and dealt with chronology, especially thedating of events in the life of Jesus.Around 1611, Kepler circulated a manuscript of what would eventually be published (posthumously) asSomnium[The Dream]. Part of the purpose ofSomniumwas to describe what practicing astronomy would be like from the perspective of another planet, to show the feasibility of a non-geocentric system. The manuscript, which disappeared after changing hands several times, described a fantastic trip to the Moon; it was part allegory, part autobiography, and part treatise on interplanetary travel (and is sometimes described as the first work of science fiction). Years later, a distorted version of the story may have instigated the witchcraft trial against his mother, as the mother of the narrator consults a demon to learn the means of space travel. Following her eventual acquittal, Kepler composed 223 footnotes to the story—several times longer than the actual text—which explained the allegorical aspects as well as the considerable scientific content (particularly regarding lunar geography) hidden within the text.[46]

Later life

[edit]Troubles

[edit]

In 1611, the growing political-religious tension in Prague came to a head. Emperor Rudolf—whose health was failing—was forced to abdicate asKing of Bohemiaby his brotherMatthias.Both sides sought Kepler's astrological advice, an opportunity he used to deliver conciliatory political advice (with little reference to the stars, except in general statements to discourage drastic action). However, it was clear that Kepler's future prospects in the court of Matthias were dim.[47]

Also in that year, Barbara Kepler contractedHungarian spotted fever,then began havingseizures.As Barbara was recovering, Kepler's three children all fell sick with smallpox; Friedrich, 6, died. Following his son's death, Kepler sent letters to potential patrons inWürttembergandPadua.At theUniversity of Tübingenin Württemberg, concerns over Kepler's perceivedCalvinistheresies in violation of theAugsburg Confessionand theFormula of Concordprevented his return. TheUniversity of Padua—on the recommendation of the departing Galileo—sought Kepler to fill the mathematics professorship, but Kepler, preferring to keep his family in German territory, instead travelled to Austria to arrange a position as teacher and district mathematician inLinz.However, Barbara relapsed into illness and died shortly after Kepler's return.[48]

Kepler postponed the move to Linz and remained in Prague until Rudolf's death in early 1612, though between political upheaval, religious tension, and family tragedy (along with the legal dispute over his wife's estate), Kepler could do no research. Instead, he pieced together a chronology manuscript,Eclogae Chronicae,from correspondence and earlier work. Upon succession as Holy Roman Emperor, Matthias re-affirmed Kepler's position (and salary) as imperial mathematician but allowed him to move to Linz.[49]

Linz (1612–1630)

[edit]

In Linz, Kepler's primary responsibilities (beyond completing theRudolphine Tables) were teaching at the district school and providing astrological and astronomical services. In his first years there, he enjoyed financial security and religious freedom relative to his life in Prague—though he was excluded fromEucharistby his Lutheran church over his theological scruples. It was also during his time in Linz that Kepler had to deal with the accusation and ultimate verdict of witchcraft against his motherKatharinain the Protestant town ofLeonberg.That blow, happening only a few years after Kepler'sexcommunication,is not seen as a coincidence but as a symptom of the full-fledged assault waged by the Lutherans against Kepler.[50]

His first publication in Linz wasDe vero Anno(1613), an expanded treatise on the year of Christ's birth. He also participated in deliberations on whether to introducePope Gregory'sreformed calendarto Protestant German lands. On 30 October 1613, Kepler married Susanna Reuttinger. Following the death of his first wife Barbara, Kepler had considered 11 different matches over two years (a decision process formalized later as themarriage problem).[51]He eventually returned to Reuttinger (the fifth match) who, he wrote, "won me over with love, humble loyalty, economy of household, diligence, and the love she gave the stepchildren."[52]The first three children of this marriage (Margareta Regina, Katharina, and Sebald) died in childhood. Three more survived into adulthood: Cordula (born 1621); Fridmar (born 1623); and Hildebert (born 1625). According to Kepler's biographers, this was a much happier marriage than his first.[53]

On 8 October 1630, Kepler set out for Regensburg, hoping to collect interest on work he had done previously. A few days after reaching Regensburg, Kepler became sick, and progressively became worse. On 15 November 1630, just over a month after his arrival, he died. He was buried in a Protestant churchyard that was completely destroyed during theThirty Years' War.[54]

Christianity

[edit]Kepler's belief that God created the cosmos in an orderly fashion caused him to attempt to determine and comprehend the laws that govern the natural world, most profoundly in astronomy.[55][56]The phrase "I am merely thinking God's thoughts after Him" has been attributed to him, although this is probably a capsulized version of a writing from his hand:

Those laws [of nature] are within the grasp of the human mind; God wanted us to recognize them by creating us after his own image so that we could share in his own thoughts.[57]

Kepler advocated fortoleranceamong Christian denominations, for example arguing that Catholics and Lutherans should be able to take communion together. He wrote, "Christ the Lord neither was nor is Lutheran, nor Calvinist, nor Papist."[58]

Astronomy

[edit]Mysterium Cosmographicum

[edit]

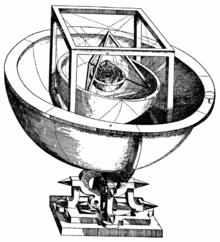

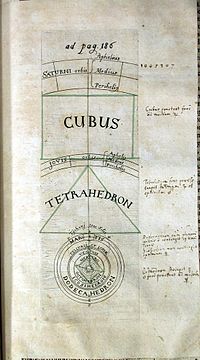

Kepler's first major astronomical work,Mysterium Cosmographicum(The Cosmographic Mystery,1596), was the first published defense of the Copernican system. Kepler claimed to have had anepiphanyon 19 July 1595, while teaching inGraz,demonstrating the periodicconjunctionofSaturnandJupiterin thezodiac:he realized thatregular polygonsbound one inscribed and one circumscribed circle at definite ratios, which, he reasoned, might be the geometrical basis of the universe. After failing to find a unique arrangement of polygons that fit known astronomical observations (even with extra planets added to the system), Kepler began experimenting with 3-dimensionalpolyhedra.He found that each of the fivePlatonic solidscould be inscribed and circumscribed by sphericalorbs;nesting these solids, each encased in a sphere, within one another would produce six layers, corresponding to the six known planets—Mercury,Venus,Earth,Mars,Jupiter, and Saturn. By ordering the solids selectively—octahedron,icosahedron,dodecahedron,tetrahedron,cube—Kepler found that the spheres could be placed at intervals corresponding to the relative sizes of each planet's path, assuming the planets circle the Sun. Kepler also found a formula relating the size of each planet's orb to the length of itsorbital period:from inner to outer planets, the ratio of increase in orbital period is twice the difference in orb radius. However, Kepler later rejected this formula, because it was not precise enough.[59]

Kepler thought theMysteriumhad revealed God's geometrical plan for the universe. Much of Kepler's enthusiasm for the Copernican system stemmed from histheologicalconvictions about the connection between the physical and thespiritual;the universe itself was an image of God, with the Sun corresponding to the Father, the stellar sphere to theSon,and the intervening space between them to theHoly Spirit.His first manuscript ofMysteriumcontained an extensive chapter reconciling heliocentrism with biblical passages that seemed to support geocentrism.[60]With the support of his mentor Michael Maestlin, Kepler received permission from the Tübingen university senate to publish his manuscript, pending removal of the Bibleexegesisand the addition of a simpler, more understandable, description of the Copernican system as well as Kepler's new ideas.Mysteriumwas published late in 1596, and Kepler received his copies and began sending them to prominent astronomers and patrons early in 1597; it was not widely read, but it established Kepler's reputation as a highly skilled astronomer. The effusive dedication, to powerful patrons as well as to the men who controlled his position in Graz, also provided a crucial doorway into thepatronage system.[61]

In 1621, Kepler published an expanded second edition ofMysterium,half as long again as the first, detailing in footnotes the corrections and improvements he had achieved in the 25 years since its first publication.[62]In terms of impact, theMysteriumcan be seen as an important first step in modernizing the theory proposed byCopernicusin hisDe revolutionibus orbium coelestium.While Copernicus sought to advance a heliocentric system in this book, he resorted toPtolemaicdevices (viz., epicycles and eccentric circles) in order to explain the change in planets' orbital speed, and also continued to use as a point of reference the center of the Earth's orbit rather than that of the Sun "as an aid to calculation and in order not to confuse the reader by diverging too much from Ptolemy." Modern astronomy owes much toMysterium Cosmographicum,despite flaws in its main thesis, "since it represents the first step in cleansing the Copernican system of the remnants of the Ptolemaic theory still clinging to it."[63]

Astronomia Nova

[edit]

The extended line of research that culminated inAstronomia Nova(A New Astronomy)—including the first twolaws of planetary motion—began with the analysis, under Tycho's direction, of the orbit of Mars. In this work Kepler introduced the revolutionary concept of planetary orbit, a path of a planet in space resulting from the action of physical causes, distinct from previously held notion of planetary orb (a spherical shell to which planet is attached). As a result of this breakthrough astronomical phenomena came to be seen as being governed by physical laws.[64]Kepler calculated and recalculated various approximations of Mars's orbit using anequant(the mathematical tool that Copernicus had eliminated with his system), eventually creating a model that generally agreed with Tycho's observations to within twoarcminutes(the average measurement error). But he was not satisfied with the complex and still slightly inaccurate result; at certain points the model differed from the data by up to eight arcminutes. The wide array of traditional mathematical astronomy methods having failed him, Kepler set about trying to fit anovoidorbit to the data.[65]

In Kepler's religious view of the cosmos, the Sun (a symbol ofGod the Father) was the source of motive force in the Solar System. As a physical basis, Kepler drew by analogy onWilliam Gilbert's theory of the magnetic soul of the Earth fromDe Magnete(1600) and on his own work on optics. Kepler supposed that the motive power (or motivespecies)[66]radiated by the Sun weakens with distance, causing faster or slower motion as planets move closer or farther from it.[67][note 1]Perhaps this assumption entailed a mathematical relationship that would restore astronomical order. Based on measurements of theaphelionandperihelionof the Earth and Mars, he created a formula in which a planet's rate of motion is inversely proportional to its distance from the Sun. Verifying this relationship throughout the orbital cycle required very extensive calculation; to simplify this task, by late 1602 Kepler reformulated the proportion in terms of geometry:planets sweep out equal areas in equal times—his second law of planetary motion.[69]

He then set about calculating the entire orbit of Mars, using the geometrical rate law and assuming an egg-shapedovoidorbit. After approximately 40 failed attempts, in late 1604 he at last hit upon the idea of an ellipse,[70]which he had previously assumed to be too simple a solution for earlier astronomers to have overlooked.[71]Finding that an elliptical orbit fit the Mars data (theVicarious Hypothesis), Kepler immediately concluded thatall planets move in ellipses, with the Sun at one focus—his first law of planetary motion. Because he employed no calculating assistants, he did not extend the mathematical analysis beyond Mars. By the end of the year, he completed the manuscript forAstronomia nova,though it would not be published until 1609 due to legal disputes over the use of Tycho's observations, the property of his heirs.[72]

Epitome of Copernican Astronomy

[edit]Since completing theAstronomia Nova,Kepler had intended to compose an astronomy textbook that would cover all the fundamentals ofheliocentric astronomy.[73]Kepler spent the next several years working on what would becomeEpitome Astronomiae Copernicanae(Epitome of Copernican Astronomy). Despite its title, which merely hints at heliocentrism, theEpitomeis less about Copernicus's work and more about Kepler's own astronomical system. TheEpitomecontained all three laws of planetary motion and attempted to explain heavenly motions through physical causes.[74]Although it explicitly extended the first two laws of planetary motion (applied to Mars inAstronomia nova) to all the planets as well as the Moon and theMedicean satellites of Jupiter,[note 2]it did not explain how elliptical orbits could be derived from observational data.[77]

Originally intended as an introduction for the uninitiated, Kepler sought to model hisEpitomeafter that of his masterMichael Maestlin,who published a well-regarded book explaining the basics ofgeocentric astronomyto non-experts.[78]Kepler completed the first of three volumes, consisting of Books I–III, by 1615 in the same question-answer format of Maestlin's and have it printed in 1617.[79]However, thebanning of Copernican booksby the Catholic Church, as well as the start of theThirty Years' War,meant that publication of the next two volumes would be delayed. In the interim, and to avoid being subject to the ban, Kepler switched the audience of theEpitomefrom beginners to that of expert astronomers and mathematicians, as the arguments became more and more sophisticated and required advanced mathematics to be understood.[78]The second volume, consisting of Book IV, was published in 1620, followed by the third volume, consisting of Books V–VII, in 1621.

Rudolphine Tables

[edit]

In the years following the completion ofAstronomia Nova,most of Kepler's research was focused on preparations for theRudolphine Tablesand a comprehensive set ofephemerides(specific predictions of planet and star positions) based on the table, though neither would be completed for many years.[80]

Kepler, at last, completed theRudolphine Tablesin 1623, which at the time was considered his major work. However, due to the publishing requirements of the emperor and negotiations with Tycho Brahe's heir, it would not be printed until 1627.[81]

Astrology

[edit]

LikePtolemy,Kepler considered astrology as the counterpart to astronomy, and as being of equal interest and value. However, in the following years, the two subjects drifted apart until astrology was no longer practiced among professional astronomers.[82]

Sir Oliver Lodgeobserved that Kepler was somewhat disdainful of astrology in his own day, as he was "continually attacking and throwing sarcasm at astrology, but it was the only thing for which people would pay him, and on it after a fashion he lived."[83]Nonetheless, Kepler spent a huge amount of time trying to restore astrology on a firmer philosophical footing, composing numerous astrological calendars, more than 800 nativities, and a number of treaties dealing with the subject of astrology proper.[84]

De Fundamentis

[edit]In his bid to become imperial astronomer, Kepler wroteDe Fundamentis(1601), whose full title can be translated as “On Giving Astrology Sounder Foundations”, as a short foreword to one of his yearly almanacs.[85]

In this work, Kepler describes the effects of the Sun, Moon, and the planets in terms of their light and their influences upon humors, finalizing with Kepler's view that the Earth possesses a soul with some sense of geometry. Stimulated by the geometric convergence of rays formed around it, theworld-soulis sentient but not conscious. As a shepherd is pleased by the piping of a flute without understanding the theory of musical harmony, so likewise Earth responds to the angles and aspects made by the heavens but not in a conscious manner. Eclipses are important as omens because the animal faculty of the Earth is violently disturbed by the sudden intermission of light, experiencing something like emotion and persisting in it for some time.[82]

Kepler surmises that the Earth has "cycles of humors" as living animals do, and gives for an example that "the highest tides of the sea are said by sailors to return after nineteen years around the same days of the year". (This may refer to the 18.6-yearlunar node precession cycle.) Kepler advocates searching for such cycles by gathering observations over a period of many years, "and so far this observation has not been made".[86]

Tertius Interveniens

[edit]Kepler andHelisaeus Roeslinengaged in a series of published attacks and counter-attacks on the importance of astrology after the supernova of 1604; around the same time, physician Philip Feselius published a work dismissing astrology altogether (and Roeslin's work in particular).[87]

In response to what Kepler saw as the excesses of astrology, on the one hand, and overzealous rejection of it, on the other, Kepler preparedTertius Interveniens(1610). Nominally this work—presented to the common patron of Roeslin and Feselius—was a neutral mediation between the feuding scholars (the titled meaning "Third-party interventions" ), but it also set out Kepler's general views on the value of astrology, including some hypothesized mechanisms of interaction between planets and individual souls. While Kepler considered most traditional rules and methods of astrology to be the "evil-smelling dung" in which "an industrious hen" scrapes, there was an "occasional grain-seed, indeed, even a pearl or a gold nugget" to be found by the conscientious scientific astrologer.[88]

Music

[edit]Harmonice Mundi

[edit]

Kepler was convinced "that the geometrical things have provided the Creator with the model for decorating the whole world".[89]InHarmonice Mundi(1619), he attempted to explain the proportions of the natural world—particularly the astronomical and astrological aspects—in terms of music.[note 3]The central set of "harmonies" was themusica universalisor "music of the spheres", which had been studied byPythagoras,Ptolemyand others before Kepler; in fact, soon after publishingHarmonice Mundi,Kepler was embroiled in a priority dispute withRobert Fludd,who had recently published his own harmonic theory.[90]

Kepler began by exploring regular polygons andregular solids,including the figures that would come to be known asKepler's solids.From there, he extended his harmonic analysis to music, meteorology, and astrology; harmony resulted from the tones made by the souls of heavenly bodies—and in the case of astrology, the interaction between those tones and human souls. In the final portion of the work (Book V), Kepler dealt with planetary motions, especially relationships betweenorbital velocityand orbital distance from the Sun. Similar relationships had been used by other astronomers, but Kepler—with Tycho's data and his own astronomical theories—treated them much more precisely and attached new physical significance to them.[91]

Among many other harmonies, Kepler articulated what came to be known as the third law of planetary motion. He tried many combinations until he discovered that (approximately) "The square of the periodic times are to each other as the cubes of the mean distances."Although he gives the date of this epiphany (8 March 1618), he does not give any details about how he arrived at this conclusion.[92]However, the wider significance for planetary dynamics of this purely kinematical law was not realized until the 1660s. When conjoined withChristiaan Huygens' newly discovered law of centrifugal force, it enabledIsaac Newton,Edmund Halley,and perhapsChristopher WrenandRobert Hooketo demonstrate independently that the presumed gravitational attraction between the Sun and its planets decreased with the square of the distance between them.[93]This refuted the traditional assumption of scholastic physics that the power of gravitational attraction remained constant with distance whenever it applied between two bodies, such as was assumed by Kepler and also by Galileo in his mistaken universal law that gravitational fall is uniformly accelerated, and also by Galileo's student Borrelli in his 1666 celestial mechanics.[94]

Optics

[edit]Astronomiae Pars Optica

[edit]

As Kepler slowly continued analyzing Tycho's Mars observations—now available to him in their entirety—and began the slow process of tabulating theRudolphine Tables,Kepler also picked up the investigation of the laws of optics from his lunar essay of 1600. Both lunar andsolar eclipsespresented unexplained phenomena, such as unexpected shadow sizes, the red color of a total lunar eclipse, and the reportedly unusual light surrounding a total solar eclipse. Related issues ofatmospheric refractionapplied toallastronomical observations. Through most of 1603, Kepler paused his other work to focus on optical theory; the resulting manuscript, presented to the emperor on 1 January 1604, was published asAstronomiae Pars Optica(The Optical Part of Astronomy). In it, Kepler described theinverse-square lawgoverning the intensity of light, reflection by flat and curved mirrors, and principles ofpinhole cameras,as well as the astronomical implications of optics such asparallaxand the apparent sizes of heavenly bodies. He also extended his study of optics to the human eye, and is generally considered by neuroscientists to be the first to recognize that images are projected inverted and reversed by theeye's lensonto theretina.The solution to this dilemma was not of particular importance to Kepler as he did not see it as pertaining to optics, although he did suggest that the image was later corrected "in the hollows of the brain" due to the "activity of the Soul."[95]

Today,Astronomiae Pars Opticais generally recognized as the foundation of modern optics (though thelaw of refractionis conspicuously absent).[96]With respect to the beginnings ofprojective geometry,Kepler introduced the idea of continuous change of a mathematical entity in this work. He argued that if afocusof aconic sectionwere allowed to move along the line joining the foci, the geometric form would morph or degenerate, one into another. In this way, anellipsebecomes aparabolawhen a focus moves toward infinity, and when two foci of an ellipse merge into one another, a circle is formed. As the foci of a hyperbola merge into one another, the hyperbola becomes a pair of straight lines. He also assumed that if a straight line is extended to infinity it will meet itself at a singlepoint at infinity,thus having the properties of a large circle.[97]

Dioptrice

[edit]In the first months of 1610,Galileo Galilei—using his powerful newtelescope—discovered four satellites orbiting Jupiter. Upon publishing his account asSidereus Nuncius[Starry Messenger], Galileo sought the opinion of Kepler, in part to bolster the credibility of his observations. Kepler responded enthusiastically with a short published reply,Dissertatio cum Nuncio Sidereo[Conversation with the Starry Messenger]. He endorsed Galileo's observations and offered a range of speculations about the meaning and implications of Galileo's discoveries and telescopic methods, for astronomy and optics as well as cosmology and astrology. Later that year, Kepler published his own telescopic observations of the moons inNarratio de Jovis Satellitibus,providing further support of Galileo. To Kepler's disappointment, however, Galileo never published his reactions (if any) toAstronomia Nova.[98]

Kepler also started a theoretical and experimental investigation of telescopic lenses using a telescope borrowed from Duke Ernest of Cologne.[99]The resulting manuscript was completed in September 1610 and published asDioptricein 1611. In it, Kepler set out the theoretical basis ofdouble-convex converging lensesanddouble-concave diverging lenses—and how they are combined to produce aGalilean telescope—as well as the concepts ofrealvs.virtualimages, upright vs. inverted images, and the effects of focal length on magnification and reduction. He also described an improved telescope—now known as theastronomicalorKeplerian telescope—in which two convex lenses can produce higher magnification than Galileo's combination of convex and concave lenses.[100]

Mathematics and physics

[edit]

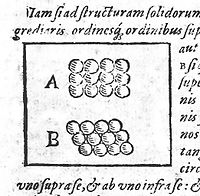

As a New Year's gift that year (1611), he also composed for his friend and some-time patron, Baron Wackher von Wackhenfels, a short pamphlet entitledStrena Seu de Nive Sexangula(A New Year's Gift of Hexagonal Snow). In this treatise, he published the first description of the hexagonal symmetry of snowflakes and, extending the discussion into a hypotheticalatomisticphysical basis for the symmetry, posed what later became known as theKepler conjecture,a statement about the most efficient arrangement for packing spheres.[101][102]

Kepler wrote the influential mathematical treatiseNova stereometria doliorum vinariorumin 1613, on measuring the volume of containers such as wine barrels, which was published in 1615.[103]Kepler also contributed to the development of infinitesimal methods and numerical analysis, including iterative approximations, infinitesimals, and the early use of logarithms and transcendental equations.[104][105]Kepler's work on calculating volumes of shapes, and on finding the optimal shape of a wine barrel, were significant steps toward the development ofcalculus.[106]Simpson's rule,an approximation method used inintegral calculus,is known in German asKeplersche Fassregel(Kepler's barrel rule).[107]

Legacy

[edit]Reception of his astronomy

[edit]Kepler's laws of planetary motionwere not immediately accepted. Several major figures such asGalileoandRené Descartescompletely ignored Kepler'sAstronomia nova.Many astronomers, including Kepler's teacher, Michael Maestlin, objected to Kepler's introduction of physics into his astronomy. Some adopted compromise positions.Ismaël Bullialdusaccepted elliptical orbits but replaced Kepler's area law with uniform motion in respect to the empty focus of the ellipse, whileSeth Wardused an elliptical orbit with motions defined by an equant.[108][109][110]

Several astronomers tested Kepler's theory, and its various modifications, against astronomical observations. Two transits of Venus and Mercury across the face of the sun provided sensitive tests of the theory, under circumstances when these planets could not normally be observed. In the case of the transit of Mercury in 1631, Kepler had been extremely uncertain of the parameters for Mercury, and advised observers to look for the transit the day before and after the predicted date.Pierre Gassendiobserved the transit on the date predicted, a confirmation of Kepler's prediction.[111]This was the first observation of a transit of Mercury. However, his attempt to observe thetransit of Venusjust one month later was unsuccessful due to inaccuracies in the Rudolphine Tables. Gassendi did not realize that it was not visible from most of Europe, including Paris.[112]Jeremiah Horrocks,who observed the1639 Venus transit,had used his own observations to adjust the parameters of the Keplerian model, predicted the transit, and then built apparatus to observe the transit. He remained a firm advocate of the Keplerian model.[113][114][115]

Epitome of Copernican Astronomywas read by astronomers throughout Europe, and following Kepler's death, it was the main vehicle for spreading Kepler's ideas. In the period 1630–1650, this book was the most widely used astronomy textbook, winning many converts to ellipse-based astronomy.[74]However, few adopted his ideas on the physical basis for celestial motions. In the late 17th century, a number of physical astronomy theories drawing from Kepler's work—notably those ofGiovanni Alfonso BorelliandRobert Hooke—began to incorporate attractive forces (though not the quasi-spiritual motive species postulated by Kepler) and the Cartesian concept ofinertia.[116]This culminated in Isaac Newton'sPrincipia Mathematica(1687), in which Newton derived Kepler's laws of planetary motion from a force-based theory ofuniversal gravitation,[117]a mathematical challenge later known as "solving theKepler problem".[118]

History of science

[edit]

Beyond his role in the historical development of astronomy and natural philosophy, Kepler has loomed large in thephilosophyandhistoriography of science.Kepler and his laws of motion were central to early histories of astronomy such asJean-Étienne Montucla's 1758Histoire des mathématiquesandJean-Baptiste Delambre's 1821Histoire de l'astronomie moderne.These and other histories written from anEnlightenmentperspective treated Kepler's metaphysical and religious arguments with skepticism and disapproval, but laterRomantic-era natural philosophers viewed these elements as central to his success. William Whewell,in his influentialHistory of the Inductive Sciencesof 1837, found Kepler to be the archetype of the inductive scientific genius; in hisPhilosophy of the Inductive Sciencesof 1840, Whewell held Kepler up as the embodiment of the most advanced forms ofscientific method.Similarly,Ernst Friedrich Apelt—the first to extensively study Kepler's manuscripts, after their purchase byCatherine the Great—identified Kepler as a key to the "Revolution of the sciences". Apelt, who saw Kepler's mathematics, aesthetic sensibility, physical ideas, and theology as part of a unified system of thought, produced the first extended analysis of Kepler's life and work.[119]

Alexandre Koyré's work on Kepler was, after Apelt, the first major milestone in historical interpretations of Kepler's cosmology and its influence. In the 1930s and 1940s, Koyré, and a number of others in the first generation of professional historians of science, described the "Scientific Revolution"as the central event in the history of science, and Kepler as a (perhaps the) central figure in the revolution. Koyré placed Kepler's theorization, rather than his empirical work, at the center of the intellectual transformation from ancient to modern world-views. Since the 1960s, the volume of historical Kepler scholarship has expanded greatly, including studies of his astrology and meteorology, his geometrical methods, the role of his religious views in his work, his literary and rhetorical methods, his interaction with the broader cultural and philosophical currents of his time, and even his role as an historian of science.[120]

Philosophers of science—such asCharles Sanders Peirce,Norwood Russell Hanson,Stephen Toulmin,andKarl Popper—have repeatedly turned to Kepler: examples ofincommensurability,analogical reasoning,falsification, and many other philosophical concepts have been found in Kepler's work. PhysicistWolfgang Paulieven used Kepler's priority dispute with Robert Fludd to explore the implications ofanalytical psychologyon scientific investigation.[121]

Editions and translations

[edit]Modern translations of a number of Kepler's books appeared in the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries, the systematic publication of his collected works began in 1937 (and is nearing completion in the early 21st century).

An edition in eight volumes,Kepleri Opera omnia,was prepared by Christian Frisch (1807–1881), during 1858 to 1871, on the occasion of Kepler's 300th birthday. Frisch's edition only included Kepler's Latin, with a Latin commentary.

A new edition was planned beginning in 1914 byWalther von Dyck(1856–1934). Dyck compiled copies of Kepler's unedited manuscripts, using international diplomatic contacts to convince the Soviet authorities to lend him the manuscripts kept in Leningrad for photographic reproduction. These manuscripts contained several works by Kepler that had not been available to Frisch. Dyck's photographs remain the basis for the modern editions of Kepler's unpublished manuscripts.

Max Caspar (1880–1956) published his German translation of Kepler'sMysterium Cosmographicumin 1923. Both Dyck and Caspar were influenced in their interest in Kepler by mathematicianAlexander von Brill(1842–1935). Caspar became Dyck's collaborator, succeeding him as project leader in 1934, establishing theKepler-Kommissionin the following year. Assisted by Martha List (1908–1992) and Franz Hammer (1898–1969), Caspar continued editorial work during World War II. Max Caspar also published a biography of Kepler in 1948.[122]The commission was later chaired by Volker Bialas (during 1976–2003) andUlrich Grigull(during 1984–1999) andRoland Bulirsch(1998–2014).[123][124]

Cultural influence and eponymy

[edit]

Kepler has acquired a popular image as an icon of scientific modernity and a man before his time; science popularizerCarl Sagandescribed him as "the firstastrophysicistand the last scientific astrologer ".[125]The debate over Kepler's place in the Scientific Revolution has produced a wide variety of philosophical and popular treatments. One of the most influential isArthur Koestler's 1959The Sleepwalkers,in which Kepler is unambiguously the hero (morally and theologically as well as intellectually) of the revolution.[126]

A well-received historical novel byJohn Banville,Kepler(1981), explored many of the themes developed in Koestler's non-fiction narrative and in the philosophy of science.[127]A 2004 nonfiction book,Heavenly Intrigue,suggested that Kepler murdered Tycho Brahe to gain access to his data.[128]

In Austria, a silver collector's10-euro Johannes Kepler silver coinwas minted in 2002. The reverse side of the coin has a portrait of Kepler, who spent some time teaching in Graz and the surrounding areas. Kepler was acquainted withPrince Hans Ulrich von Eggenbergpersonally, and he probably influenced the construction ofEggenberg Castle(the motif of the obverse of the coin). In front of him on the coin is the model of nested spheres and polyhedra fromMysterium Cosmographicum.[129]

The German composerPaul Hindemithwrote an opera about Kepler entitledDie Harmonie der Welt(1957), and during the prolonged process of its creation, he also wrote a symphony of the same name based on the musical ideas he developed for it.[130]Hindemith's opera inspiredJohn RodgersandWillie RuffofYale Universityto create asynthesizercomposition based on Kepler's scheme for representing planetary motion with music.[131]Philip Glasswrote an opera calledKepler(2009) based on Kepler's life, with a libretto in German and Latin by Martina Winkel.[132]

Directly named for Kepler's contribution to science areKepler's laws of planetary motion;Kepler's SupernovaSN 1604, which he observed and described; theKepler–Poinsot polyhedra(a set of geometrical constructions), two of which were described by him; and theKepler conjectureonsphere packing.Places and entitiesnamed in his honorinclude multiple city streets and squares, several educational institutions,an asteroid,and both alunarand aMartian crater.

TheKepler space telescopeobserved 530,506 stars and detected2,778 confirmed planetsas of 16 June 2023, with many of them being named after the telescope and Kepler himself.[133][134]

Works

[edit]- Mysterium Cosmographicum(The Sacred Mystery of the Cosmos) (1596)

- De Fundamentis Astrologiae Certioribus(On Firmer Fundaments of Astrology) (1601)

- Astronomiae pars optica(in Latin). Frankfurt am Main: Claude de Marne. 1604.

- De Stella nova in pede Serpentarii(On the New Star in Ophiuchus's Foot) (1606)

- Astronomia nova(New Astronomy) (1609)

- Tertius Interveniens(Third-party Interventions) (1610)

- Dissertatio cum Nuncio Sidereo(Conversation with the Starry Messenger) (1610)

- Dioptrice(1611)

- De nive sexangula(On the Six-Cornered Snowflake) (1611)

- De vero Anno, quo aeternus Dei Filius humanam naturam in Utero benedictae Virginis Mariae assumpsit(1614)[135]

- Eclogae Chronicae(1615, published withDissertatio cum Nuncio Sidereo)

- Nova stereometria doliorum vinariorum(New Stereometry of Wine Barrels) (1615)

- Ephemerides nouae motuum coelestium(1617–30)

- Epitome astronomiae copernicanae(in Latin). Linz: Johann Planck. 1618.

- Epitome astronomiae Copernicanae. 1–3, De doctrina sphaerica(in Latin). Vol. 44199. Linz: Johann Planck. 1618.

- Epitome astronomiae Copernicanae. 4, Doctrina theorica. 1, Physica coelestis(in Latin). Vol. 4. Linz: Gottfried Tambach. 1622.

- Epitome astronomiae Copernicanae. 5–7, Doctrina theorica(in Latin). Vol. 44323. Linz: Gottfried Tambach. 1621.

- De cometis(in Latin). Augsburg: Sebastian Müller. 1619.

- Harmonice Mundi(Harmony of the Worlds) (1619)

- Mysterium cosmographicum(The Sacred Mystery of the Cosmos), 2nd edition (1621)

- Tabulae Rudolphinae(Rudolphine Tables) (1627)

- Somnium(The Dream) (1634) (English translation on Google Books preview)

- [Opere](in Latin). Vol. 1. Frankfurt am Main: Heyder & Zimmer. 1858.

- [Opere](in Latin). Vol. 2. Frankfurt am Main: Heyder & Zimmer. 1859.

- [Opere](in Latin). Vol. 3. Frankfurt am Main: Heyder & Zimmer. 1860.

- [Opere](in Latin). Vol. 4. Frankfurt am Main: Heyder & Zimmer. 1863.

- [Opere](in Latin). Vol. 5. Frankfurt am Main: Heyder & Zimmer. 1864.

- [Opere](in Latin). Vol. 6. Frankfurt am Main: Heyder & Zimmer. 1866.

- [Opere](in Latin). Vol. 7. Frankfurt am Main: Heyder & Zimmer. 1868.

- [Opere](in Latin). Vol. 8. Frankfurt am Main: Heyder & Zimmer. 1870.

- [Opere](in Latin). Vol. 9. Frankfurt am Main: Heyder & Zimmer. 1871.

A critical edition of Kepler's collected works (Johannes Kepler Gesammelte Werke,KGW) in 22 volumes is being edited by theKepler-Kommission(founded 1935) on behalf of theBayerische Akademie der Wissenschaften.

- Vol. 1:Mysterium Cosmographicum. De Stella Nova.Ed. M. Caspar. 1938, 2nd ed. 1993. PaperbackISBN3-406-01639-1.

- Vol. 2:Astronomiae pars optica.Ed. F. Hammer. 1939, PaperbackISBN3-406-01641-3.

- Vol. 3:Astronomia Nova.Ed. M. Caspar. 1937. IV, 487 p. 2. ed. 1990. PaperbackISBN3-406-01643-X.Semi-parchmentISBN3-406-01642-1.

- Vol. 4:Kleinere Schriften 1602–1611. Dioptrice.Ed. M. Caspar, F. Hammer. 1941.ISBN3-406-01644-8.

- Vol. 5:Chronologische Schriften.Ed. F. Hammer. 1953. Out-of-print.

- Vol. 6:Harmonice Mundi.Ed. M. Caspar. 1940, 2nd ed. 1981,ISBN3-406-01648-0.

- Vol. 7:Epitome Astronomiae Copernicanae.Ed. M. Caspar. 1953, 2nd ed. 1991.ISBN3-406-01650-2,PaperbackISBN3-406-01651-0.

- Vol. 8:Mysterium Cosmographicum. Editio altera cum notis. De Cometis. Hyperaspistes.Commentary F. Hammer. 1955. PaperbackISBN3-406-01653-7.

- Vol 9:Mathematische Schriften.Ed. F. Hammer. 1955, 2nd ed. 1999. Out-of-print.

- Vol. 10:Tabulae Rudolphinae.Ed. F. Hammer. 1969.ISBN3-406-01656-1.

- Vol. 11,1:Ephemerides novae motuum coelestium.Commentary V. Bialas. 1983.ISBN3-406-01658-8,PaperbackISBN3-406-01659-6.

- Vol. 11,2:Calendaria et Prognostica. Astronomica minora. Somnium.Commentary V. Bialas, H. Grössing. 1993.ISBN3-406-37510-3,PaperbackISBN3-406-37511-1.

- Vol. 12:Theologica. Hexenprozeß. Tacitus-Übersetzung. Gedichte.Commentary J. Hübner, H. Grössing, F. Boockmann, F. Seck. Directed by V. Bialas. 1990.ISBN3-406-01660-X,PaperbackISBN3-406-01661-8.

- Vols. 13–18: Letters:

- Vol. 13:Briefe 1590–1599.Ed. M. Caspar. 1945. 432 p.ISBN3-406-01663-4.

- Vol. 14:Briefe 1599–1603.Ed. M. Caspar. 1949. Out-of-print. 2nd ed. in preparation.

- Vol 15:Briefe 1604–1607.Ed. M. Caspar. 1951. 2nd ed. 1995.ISBN3-406-01667-7.

- Vol. 16:Briefe 1607–1611.Ed. M. Caspar. 1954.ISBN3-406-01668-5.

- Vol. 17:Briefe 1612–1620.Ed. M. Caspar. 1955.ISBN3-406-01671-5.

- Vol. 18:Briefe 1620–1630.Ed. M. Caspar. 1959.ISBN3-406-01672-3.

- Vol. 19:Dokumente zu Leben und Werk.Commentary M. List. 1975.ISBN978-3-406-01674-5.

- Vols. 20–21: manuscripts

- Vol. 20, 1:Manuscripta astronomica (I). Apologia, De motu Terrae, Hipparchus etc.Commentary V. Bialas. 1988.ISBN3-406-31501-1.PaperbackISBN3-406-31502-X.

- Vol. 20, 2:Manuscripta astronomica (II). Commentaria in Theoriam Martis.Commentary V. Bialas. 1998. PaperbackISBN3-406-40593-2.

- Vol. 21, 1:Manuscripta astronomica (III) et mathematica. De Calendario Gregoriano.In preparation.

- Vol. 21, 2:Manuscripta varia.In preparation.

- Vol. 22: General index, in preparation.

The Kepler-Kommission also publishesBibliographia Kepleriana(2nd edition List, 1968), a complete bibliography of editions of Kepler's works, with a supplementary volume to the second edition (ed. Hamel 1998).

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^"Kepler's decision to base his causal explanation of planetary motion on a distance-velocity law, rather than on uniform circular motions of compounded spheres, marks a major shift from ancient to modern conceptions of science... [Kepler] had begun with physical principles and had then derived a trajectory from it, rather than simply constructing new models. In other words, even before discovering the area law, Kepler had abandoned uniform circular motion as a physical principle."[68]

- ^By 1621 or earlier, Kepler recognized that Jupiter's moons obey his third law. Kepler contended that rotating massive bodies communicate their rotation to their satellites, so that the satellites are swept around the central body; thus the rotation of the Sun drives the revolutions of the planets and the rotation of the Earth drives the revolution of the Moon. In Kepler's era, no one had any evidence of Jupiter's rotation. However, Kepler argued that the force by which a central body causes its satellites to revolve around it, weakens with distance; consequently, satellites that are farther from the central body revolve slower. Kepler noted that Jupiter's moons obeyed this pattern and he inferred that a similar force was responsible. He also noted that the orbital periods and semi-major axes of Jupiter's satellites were roughly related by a 3/2 power law, as are the orbits of the six (then known) planets. However, this relation was approximate: the periods of Jupiter's moons were known within a few percent of their modern values, but the moons' semi-major axes were determined less accurately. Kepler discussed Jupiter's moons in hisSummary of Copernican Astronomy:[75][76]

(4) However, the credibility of this [argument] is proved by the comparison of the four [moons] of Jupiter and Jupiter with the six planets and the Sun. Because, regarding the body of Jupiter, whether it turns around its axis, we don't have proofs for what suffices for us [regarding the rotation of ] the body of the Earth and especially of the Sun, certainly [as reason proves to us]: but reason attests that, just as it is clearly [true] among the six planets around the Sun, so also it is among the four [moons] of Jupiter, because around the body of Jupiter any [satellite] that can go farther from it orbits slower, and even that [orbit's period] is not in the same proportion, but greater [than the distance from Jupiter]; that is, 3/2 (sescupla) of the proportion of each of the distances from Jupiter, which is clearly the very [proportion] as [is used for] the six planets above. In his [book]The World of Jupiter[Mundus Jovialis,1614],[Simon] Mayr[1573–1624] presents these distances, from Jupiter, of the four [moons] of Jupiter: 3, 5, 8, 13 (or 14 [according to] Galileo)... Mayr presents their time periods: 1 day 18 1/2 hours, 3 days 13 1/3 hours, 7 days 3 hours, 16 days 18 hours: for all [of these data] the proportion is greater than double, thus greater than [the proportion] of the distances 3, 5, 8, 13 or 14, although less than [the proportion] of the squares, which double the proportions of the distances, namely 9, 25, 64, 169 or 196, just as [a power of] 3/2 is also greater than 1 but less than 2.

- ^The opening of the movieMars et AvrilbyMartin Villeneuveis based on German astronomer Johannes Kepler's cosmological model from the 17th century,Harmonice Mundi,in which the harmony of the universe is determined by the motion of celestial bodies.Benoît Charestalso composed the score according to this theory.

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^Liscia, Daniel A. Di."Johannes Kepler".InZalta, Edward N.(ed.).Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- ^"Kepler".Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary.

- ^Dudenredaktion; Kleiner, Stefan; Knöbl, Ralf (2015) [First published 1962].Das Aussprachewörterbuch[The Pronunciation Dictionary] (in German) (7th ed.). Berlin: Dudenverlag. pp. 487, 505.ISBN978-3-411-04067-4.

- ^Krech, Eva-Maria; Stock, Eberhard; Hirschfeld, Ursula; Anders, Lutz Christian (2009).Deutsches Aussprachewörterbuch[German Pronunciation Dictionary] (in German). Berlin: Walter de Gruyter. pp. 628, 646.ISBN978-3-11-018202-6.

- ^Jeans, Susi(2013) [2001]."Kepler [Keppler], Johannes".Grove Music Online.Revised byH. Floris Cohen.Oxford:Oxford University Press.doi:10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.14903.ISBN978-1-56159-263-0.Retrieved26 September2021.(subscription orUK public library membershiprequired)

- ^Voelkel, James R. (2001)."Commentary on Ernan McMullin," The Impact of Newton's Principia on the Philosophy of Science "".Philosophy of Science.68(3): 319–326.doi:10.1086/392885.ISSN0031-8248.JSTOR3080920.S2CID144781947.

- ^"DPMA | Johannes Kepler".

- ^"Johannes Kepler: His Life, His Laws and Times | NASA".Archived fromthe originalon 24 June 2021.Retrieved1 September2023.

- ^"Molecular Expressions: Science, Optics and You – Timeline – Johannes Kepler".

- ^"Kepler, the Father of Science Fiction".bbvaopenmind.16 November 2015.

- ^Popova, Maria (27 December 2019)."How Kepler Invented Science Fiction and Defended His Mother in a Witchcraft Trial While Revolutionizing Our Understanding of the Universe".themarginalian.org.

- ^Coullet, Pierre; San Martin, Jaime; Tirapegui, Enrique (2022)."Kepler in search of the 'Anaclastic'".Chaos, Solitons & Fractals.164.Bibcode:2022CSF...16412695C.doi:10.1016/j.chaos.2022.112695.S2CID252834988.

- ^"Keplerian telescope | Optical Design, Refracting, Astronomy".Encyclopaedia Britannica.

- ^Tunnacliffe, AH; Hirst JG (1996).Optics.Kent, England. pp. 233–237.ISBN978-0-900099-15-1.

{{cite book}}:CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^Dooley, Brendan (June 2021). "From astrology to astronomy: renaissance and early modern perspectives".Berliner Theologische Zeitschrift.38(1). Walter de Gruyter GmbH: 156–175.doi:10.1515/bthz-2021-0010.

From ancient times through the seventeenth century European astronomy and astrology remained two sides of the same coin

- ^Omodeo, Pietro Daniel (August 2015). "The 'Impiety' of Kepler's shift from mathematical astronomy to celestial physics".Annalen der Physik.527(7–8). Wiley.doi:10.1002/andp.201500238.hdl:11858/00-001M-0000-002A-8F0F-E.

- ^Barker and Goldstein. "Theological Foundations of Kepler's Astronomy",Osiris,16, 2001, pp. 112–113.

- ^Kepler.New Astronomy,title page, tr. Donohue, pp. 26–27

- ^Kepler.New Astronomy,p. 48

- ^Epitome of Copernican AstronomyinGreat Books of the Western World,Vol. 15, p. 845

- ^Stephenson.Kepler's Physical Astronomy,pp. 1–2; Dear,Revolutionizing the Sciences,pp. 74–78

- ^Caspar.Kepler,pp. 29–36; Connor.Kepler's Witch,pp. 23–46.

- ^abKoestler.The Sleepwalkers,p. 234 (translated from Kepler's family horoscope).

- ^Caspar.Kepler,pp. 36–38; Connor.Kepler's Witch,pp. 25–27.

- ^Connor, James A.Kepler's Witch(2004), p. 58.

- ^abBarker, Peter; Goldstein, Bernard R. "Theological Foundations of Kepler's Astronomy", Osiris, 2nd Series, Vol. 16, Sciencein Theistic Contexts: Cognitive Dimensions(2001), p. 96.

- ^Westman, Robert S. "Kepler's Early Physico-Astrological Problematic,"Journal for the History of Astronomy,32(2001): 227–236.

- ^Barker, Peter; Goldstein, Bernard R. (January 2001)."Theological Foundations of Kepler's Astronomy".Osiris.16:88–113.doi:10.1086/649340.ISSN0369-7827.S2CID145170215.

- ^Caspar.Kepler,pp. 38–52; Connor.Kepler's Witch,pp. 49–69.

- ^Caspar,Kepler.pp. 50–51.

- ^Caspar,Kepler.pp. 58–65.

- ^Caspar,Kepler.pp. 71–75.

- ^Connor.Kepler's Witch,pp. 89–100, 114–116; Caspar.Kepler,pp. 75–77

- ^Caspar.Kepler,pp. 85–86.

- ^Caspar,Kepler,pp. 86–89

- ^Caspar,Kepler,pp. 89–100

- ^Caspar,Kepler,pp. 100–108.

- ^Caspar,Kepler,p. 110.

- ^Caspar,Kepler,pp. 108–111.

- ^Caspar,Kepler,pp. 111–122.

- ^Caspar,Kepler,pp. 149–153

- ^Caspar,Kepler,pp. 146–148, 159–177

- ^Caspar,Kepler,p. 151.

- ^Caspar,Kepler,pp. 151–153.

- ^Caspar,Kepler,pp. 153–157

- ^Lear,Kepler's Dream,pp. 1–78

- ^Caspar,Kepler,pp. 202–204

- ^Connor,Kepler's Witch,pp. 222–226; Caspar,Kepler,pp. 204–207

- ^Caspar,Kepler,pp. 208–211

- ^Mazer, Arthur (2010).Shifting the Earth: The Mathematica Quest to Understand the Motion of the Universe.Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.ISBN978-1-118-02427-0.

- ^Ferguson, Thomas S.(1989)."Who solved the secretary problem?".Statistical Science.4(3): 282–289.doi:10.1214/ss/1177012493.JSTOR2245639.

When the celebrated German astronomer, Johannes Kepler (1571–1630), lost his first wife to cholera in 1611, he set about finding a new wife using the same methodical thoroughness and careful consideration of the data that he used in finding the orbit of Mars to be an ellipse... The process consumed much of his attention and energy for nearly 2 years...

- ^Quotation from Connor,Kepler's Witch,p. 252, translated from an 23 October 1613 letter from Kepler to an anonymous nobleman

- ^Caspar,Kepler,pp. 220–223; Connor,Kepler's Witch,pp. 251–254.

- ^Caspar,Kepler,pp. 358–360

- ^"Johannes Kepler | Biography, Discoveries, & Facts".31 August 2023.

- ^"Astronomy – the techniques of astronomy".

- ^Letter (9/10 Apr 1599) to the Bavarian chancellor Herwart von Hohenburg. Collected in Carola Baumgardt and Jamie Callan,Johannes Kepler Life and Letters(1953), 50

- ^Rothman, Aviva (1 January 2020)."Johannes Kepler's pursuit of harmony".Physics Today.73(1): 36–42.Bibcode:2020PhT....73a..36R.doi:10.1063/PT.3.4388.ISSN0031-9228.S2CID214144110.

- ^Caspar.Kepler,pp. 60–65; see also: Barker and Goldstein, "Theological Foundations of Kepler's Astronomy."

- ^Barker and Goldstein. "Theological Foundations of Kepler's Astronomy," pp. 99–103, 112–113.

- ^Caspar.Kepler,pp. 65–71.

- ^Field.Kepler's Geometrical Cosmology,Chapter IV, pp. 73ff.

- ^Dreyer, J.L.E.A History of Astronomy fromThalesto Kepler,Dover Publications, 1953, pp. 331, 377–379.

- ^Goldstein, Bernard; Hon, Giora (2005)."Kepler's Move from Orbs to Orbits: Documenting a Revolutionary Scientific Concept".Perspectives on Science.13:74–111.doi:10.1162/1063614053714126.S2CID57559843.

- ^Caspar,Kepler,pp. 123–128

- ^On motive species, see Lindberg, "The Genesis of Kepler's Theory of Light," pp. 38–40.

- ^Koyré,The Astronomical Revolution,pp. 199–202.

- ^Peter Barker and Bernard R. Goldstein, "Distance and Velocity in Kepler's Astronomy",Annals of Science,51 (1994): 59–73, at p. 60.

- ^Caspar,Kepler,pp. 129–132

- ^Dreyer, John Louis Emil(1906).History of the Planetary Systems from Thales to Kepler.Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. p. 402.

- ^Caspar,Kepler,p. 133

- ^Caspar,Kepler,pp. 131–140; Koyré,The Astronomical Revolution,pp. 277–279

- ^Caspar,Kepler,pp. 239–240, 293–300

- ^abGingerich, "Kepler, Johannes" fromDictionary of Scientific Biography,pp. 302–304

- ^Linz ( "Lentiis ad Danubium" ), (Austria): Johann Planck, 1622, book 4, part 2,p. 554

- ^Christian Frisch, ed.,Joannis Kepleri Astronomi Opera Omnia,vol. 6 (Frankfurt-am-Main, (Germany): Heyder & Zimmer, 1866),p. 361.)

- ^Wolf,A History of Science, Technology and Philosophy,pp. 140–141; Pannekoek,A History of Astronomy,p. 252

- ^abRothman, A. (2021)."Kepler's Epitome of Copernican Astronomy in context".Centaurus.63:171–191.doi:10.1111/1600-0498.12356.ISSN0008-8994.S2CID230613099.

- ^Gingerich, Owen (1990)."Five Centuries of Astronomical Textbooks and Their Role in Teaching".The Teaching of Astronomy, Proceedings of IAU Colloq. 105, Held in Williamstown, MA, 27–30 July 1988:189.Bibcode:1990teas.conf..189G.

- ^Caspar,Kepler.pp. 178–179.

- ^Robert J. King, “Johannes Kepler and Australia”,The Globe,no. 90, 2021, pp. 15–24.

- ^abField, J. V. (1984)."A Lutheran Astrologer: Johannes Kepler".Archive for History of Exact Sciences.31(3): 189–272.Bibcode:1984AHES...31..189F.doi:10.1007/BF00327703.ISSN0003-9519.JSTOR41133735.S2CID119811074.

- ^Lodge, O.J.,"Johann Kepler" inThe World of Mathematics,Vol. 1 (1956) Ed.Newman, J.R.,Simon and Schuster,pp. 231.

- ^Boner, P. J. (2005)."Soul-Searching with Kepler: An Analysis of Anima in His Astrology".Journal for the History of Astronomy.36(1): 7–20.Bibcode:2005JHA....36....7B.doi:10.1177/002182860503600102.S2CID124764022.

- ^Simon, G. (1975)."Kepler's astrology: The direction of a reform".Vistas in Astronomy.18(1): 439–448.Bibcode:1975VA.....18..439S.doi:10.1016/0083-6656(75)90122-1.

- ^Brackenridge, J. Bruce; Rossi, Mary Ann (1979)."Johannes Kepler's on the More Certain Fundamentals of Astrology Prague 1601".Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society.123(2): 85–116.ISSN0003-049X.JSTOR986232.

- ^Caspar,Kepler,pp. 178–181

- ^Caspar,Kepler,pp. 181–185. The full title isTertius Interveniens, das ist Warnung an etliche Theologos, Medicos vnd Philosophos, sonderlich D. Philippum Feselium, dass sie bey billicher Verwerffung der Sternguckerischen Aberglauben nict das Kindt mit dem Badt aussschütten vnd hiermit jhrer Profession vnwissendt zuwider handlen,translated byC. Doris Hellmanas "Tertius Interveniens,that is warning to some theologians, medics and philosophers, especially D. Philip Feselius, that they in cheap condemnation of the star-gazer's superstition do not throw out the child with the bath and hereby unknowingly act contrary to their profession. "

- ^Quotation from Caspar,Kepler,pp. 265–266, translated fromHarmonice Mundi

- ^Caspar,Kepler,pp. 264–266, 290–293

- ^Caspar,Kepler,pp. 266–290

- ^Miller, Arthur I.(2009).Deciphering the cosmic number: the strange friendship of Wolfgang Pauli and Carl Jung.W. W. Norton & Company. p.80.ISBN978-0-393-06532-9.Retrieved7 March2011.

- ^Westfall,Never at Rest,pp. 143, 152, 402–403; Toulmin and Goodfield,The Fabric of the Heavens,p. 248; De Gandt, 'Force and Geometry in Newton's Principia', chapter 2; Wolf,History of Science, Technology and Philosophy,p. 150; Westfall,The Construction of Modern Science,chapters 7 and 8

- ^Koyré,The Astronomical Revolution,p. 502

- ^Finger, "Origins of Neuroscience," p. 74.Oxford University Press,2001.

- ^Caspar,Kepler,pp. 142–146

- ^Morris Kline,Mathematical Thought from Ancient to Modern Times,p. 299.Oxford University Press,1972.

- ^Caspar,Kepler,pp. 192–197

- ^Koestler,The Sleepwalkersp. 384

- ^Caspar,Kepler,pp. 198–202

- ^Schneer, "Kepler's New Year's Gift of a Snowflake," pp. 531–545

- ^Kepler, Johannes (1966) [1611].Hardie, Colin(ed.).De nive sexangula[The Six-sided Snowflake]. Oxford: Clarendon Press.OCLC974730.

- ^Caspar,Kepler,pp. 209–220, 227–240. In 2018 a complete English translation was published:Nova stereometria doliorum vinariorum / New solid geometry of wine barrels. Accessit stereometriæ Archimedeæ supplementum / A supplement to the Archimedean solid geometry has been added.Edited and translated, with an Introduction, byEberhard Knobloch.Paris: Les Belles Lettres, 2018.ISBN978-2-251-44832-9

- ^Belyi, Y. A. (1975)."Johannes Kepler and the development of mathematics".Vistas in Astronomy.18(1): 643–660.Bibcode:1975VA.....18..643B.doi:10.1016/0083-6656(75)90149-X.

- ^Thorvaldsen, S. (2010)."Early Numerical Analysis in Kepler's New Astronomy".Science in Context.23(1): 39–63.doi:10.1017/S0269889709990238.S2CID122605799.

- ^Cardil, Roberto (2020)."Kepler: The Volume of a Wine Barrel".Mathematical Association of America.Retrieved16 July2022.

- ^Albinus, Hans-Joachim (June 2002)."Joannes Keplerus Leomontanus: Kepler's childhood in Weil der Stadt and Leonberg 1571–1584".The Mathematical Intelligencer.24(3): 50–58.doi:10.1007/BF03024733.ISSN0343-6993.S2CID123965600.

- ^For a detailed study of the reception of Kepler's astronomy see Wilbur Applebaum,"Keplerian Astronomy after Kepler: Researches and Problems",History of Science,34(1996): 451–504.

- ^Koyré,The Astronomical Revolution,pp. 362–364

- ^North,History of Astronomy and Cosmology,pp. 355–360

- ^van Helden, Albert (1976). "The Importance of the Transit of Mercury of 1631".Journal for the History of Astronomy.7:1–10.Bibcode:1976JHA.....7....1V.doi:10.1177/002182867600700101.S2CID220916972.

- ^HM Nautical Almanac Office (10 June 2004)."1631 Transit of Venus".Archived fromthe originalon 1 October 2006.Retrieved28 August2006.

- ^Allan Chapman,"Jeremiah Horrocks, the transit of Venus, and the 'New Astronomy' in early 17th-century England",Quarterly Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society,31 (1990): 333–357.

- ^North,History of Astronomy and Cosmology,pp. 348–349

- ^Wilbur Applebaum and Robert Hatch,"Boulliau, Mercator, and Horrock'sVenus in sole visa:Three Unpublished Letters ",Journal for the History of Astronomy,14(1983): 166–179

- ^Lawrence Nolan (ed.),The Cambridge Descartes Lexicon,Cambridge University Press, 2016, "Inertia."

- ^Kuhn,The Copernican Revolution,pp. 238, 246–252

- ^Frautschi, Steven C.;Olenick, Richard P.;Apostol, Tom M.;Goodstein, David L.(2007).The Mechanical Universe: Mechanics and Heat(Advanced ed.). Cambridge [Cambridgeshire]: Cambridge University Press. p. 451.ISBN978-0-521-71590-4.OCLC227002144.

- ^Jardine, "Koyré's Kepler/Kepler's Koyré," pp. 363–367

- ^Jardine, "Koyré's Kepler/Kepler's Koyré," pp. 367–372; Shapin,The Scientific Revolution,pp. 1–2

- ^Pauli, "The Influence of Archetypical Ideas"

- ^Gingerich, introduction to Caspar'sKepler,pp. 3–4

- ^Ulrich Grigull,"Sechzig Jahre Kepler-Kommission", in: Sitzungsberichte der Bayerischen Akademie der Wissenschaften [Sitzung vom 5. Juli 1996], 1996.

- ^kepler-kommission.de. Ulf Hashagen, Walther von Dyck (1856–1934). Mathematik, Technik und Wissenschaftsorganisation an der TH München, Stuttgart, 2003.

- ^Quote fromCarl Sagan,Cosmos: A Personal Voyage,episode III: "The Harmony of the Worlds".

- ^Stephen Toulmin, Review ofThe SleepwalkersinThe Journal of Philosophy,Vol. 59, no. 18 (1962), pp. 500–503

- ^William Donahue, "A Novelist's Kepler,"Journal for the History of Astronomy,Vol. 13 (1982), pp. 135–136; "Dancing the grave dance: Science, art and religion in John Banville'sKepler,"English Studies,Vol. 86, no. 5 (October 2005), pp. 424–438

- ^Marcelo Gleiser,"Kepler in the Dock", review of Gilder and Gilder'sHeavenly Intrigue,Journal for the History of Astronomy,Vol. 35, pt. 4 (2004), pp. 487–489

- ^"Eggenberg Palace coin".Austrian Mint. Archived fromthe originalon May 31, 2011.RetrievedSeptember 9,2009.

- ^MacDonald, Calum (2004)."Review of Hindemith: Die Harmonie der Welt".Tempo.58(227): 63–66.doi:10.1017/S0040298204210063.ISSN0040-2982.JSTOR3878689.

- ^Rodgers, John; Ruff, Willie (1979)."Kepler's Harmony of the World: A Realization for the Ear".American Scientist.67(3): 286–292.Bibcode:1979AmSci..67..286R.ISSN0003-0996.JSTOR27849220.

- ^Pasachoff, Jay M.; Pasachoff, Naomi (December 2009)."Third physics opera for Philip Glass".Nature.462(7274): 724.Bibcode:2009Natur.462..724P.doi:10.1038/462724a.ISSN0028-0836.S2CID4391370.

- ^"Exoplanet and Candidate Statistics".exoplanetarchive.ipac.caltech.edu.Retrieved16 June2023.

- ^Dennis Overbye (30 October 2018)."Kepler, the Little NASA Spacecraft That Could, No Longer Can".Nytimes.Retrieved31 October2018.

- ^"... in 1614, Johannes Kepler published his bookDe vero anno quo aeternus dei filius humanum naturam in utero benedictae Virginis Mariae assumpsit,on the chronology related to the Star of Bethlehem. ",The Star of Bethlehem,Kapteyn Astronomical Institute

Sources

[edit]- Barker, Peter and Bernard R. Goldstein: "Theological Foundations of Kepler's Astronomy".Osiris,Volume 16.Science in Theistic Contexts.University of Chicago Press,2001, pp. 88–113

- Caspar, Max.Kepler;transl. and ed. byC. Doris Hellman;with a new introduction and references by Owen Gingerich; bibliographic citations by Owen Gingerich and Alain Segonds. New York: Dover, 1993.ISBN978-0-486-67605-0

- Connor, James A.Kepler's Witch: An Astronomer's Discovery of Cosmic Order Amid Religious War, Political Intrigue, and the Heresy Trial of His Mother.HarperSanFrancisco, 2004.ISBN978-0-06-052255-1

- De Gandt, Francois.Force and Geometry in Newton'sPrincipia, Translated by Curtis Wilson,Princeton University Press,1995.ISBN978-0-691-03367-9

- Dreyer, J. L. E.A History of Astronomy from Thales to Kepler.Dover Publications Inc, 1967.ISBN0-486-60079-3

- Field, J. V.Kepler's geometrical cosmology.University of Chicago Press,1988.ISBN978-0-226-24823-3

- Gilder, Joshua and Anne-Lee Gilder:Heavenly Intrigue: Johannes Kepler, Tycho Brahe, and the Murder Behind One of History's Greatest Scientific Discoveries,Doubleday (2004).ISBN978-0-385-50844-5Reviewsbookpage,

- Gingerich, Owen.The Eye of Heaven: Ptolemy, Copernicus, Kepler.American Institute of Physics, 1993.ISBN978-0-88318-863-7(Masters of modern physics; v. 7)

- Gingerich, Owen: "Kepler, Johannes" inDictionary of Scientific Biography,Volume VII. Charles Coulston Gillispie, editor. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1973

- Jardine, Nick: "Koyré's Kepler/Kepler's Koyré,"History of Science,Vol. 38 (2000), pp. 363–376

- Kepler, Johannes.Johannes Kepler New Astronomytrans. W. Donahue, foreword by O. Gingerich,Cambridge University Press1993.ISBN0-521-30131-9

- Kepler, Johannes and Christian Frisch.Joannis Kepleri Astronomi Opera Omnia(John Kepler, Astronomer; Complete Works), 8 volumes (1858–1871).vol. 1, 1858,vol. 2, 1859,vol. 3, 1860,vol. 6, 1866,vol. 7, 1868,Frankfurt am Main and Erlangen, Heyder & Zimmer, –Google Books

- Kepler, Johannes, et al.Great Books of the Western World. Volume 16: Ptolemy, Copernicus, Kepler,Chicago: Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 1952. (contains English translations by of Kepler'sEpitome,Books IV & V andHarmoniceBook 5)

- Koestler, Arthur.The Sleepwalkers:A History of Man's Changing Vision of the Universe.(1959).ISBN978-0-14-019246-9

- Koyré, Alexandre:Galilean StudiesHarvester Press, 1977.ISBN978-0-85527-354-5