Phytochrome

| Phytochrome | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Crystal structure of phytochrome.[1] | |||||||||

| Identifiers | |||||||||

| Symbol | Phytochrome | ||||||||

| Pfam | PF00360 | ||||||||

| InterPro | IPR013515 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

Phytochromesare a class ofphotoreceptor proteinsfound inplants,bacteriaandfungi.They respond to light in theredandfar-redregions of thevisible spectrumand can be classed as either Type I, which are activated by far-red light, or Type II that are activated by red light.[2]Recent advances have suggested that phytochromes also act as temperature sensors, as warmer temperatures enhance their de-activation.[3]All of these factors contribute to the plant's ability togerminate.

Phytochromes control many aspects of plant development. They regulate thegerminationofseeds(photoblasty), the synthesis ofchlorophyll,the elongation of seedlings, the size, shape and number and movement ofleavesand the timing offloweringin adult plants. Phytochromes are widely expressed across many tissues and developmental stages.[2]

Other plant photoreceptors includecryptochromesandphototropins,which respond toblueandultraviolet-A light andUVR8,which is sensitive toultraviolet-B light.

Structure

[edit]Phytochromes consist of aprotein,covalentlylinked to a light-sensingbilinchromophore.[4]The protein part comprises two identical chains (A and B). Each chain has aPAS domain,GAF domainand PHY domain. Domain arrangements in plant, bacterial and fungal phytochromes are comparable, insofar as the three N-terminal domains are always PAS, GAF and PHY domains. However C-terminal domains are more divergent. The PAS domain serves as a signal sensor and the GAF domain is responsible for binding to cGMP and also senses light signals. Together, these subunits form the phytochrome region, which regulates physiological changes in plants to changes in red and far red light conditions. In plants, red light changes phytochrome to its biologically active form, while far red light changes the protein to its biologically inactive form.

Isoforms and states

[edit]

Phytochromes are characterized by a red/far-redphotochromicity.Photochromic pigments change their "color" (spectral absorbance properties) upon light absorption. In the case of phytochrome the ground state is Pr,therindicating that it absorbs red light particularly strongly. The absorbance maximum is a sharp peak 650–670 nm, so concentrated phytochrome solutions look turquoise-blue to the human eye when viewed with white light. But once a red photon has been absorbed, the pigment undergoes a rapid conformational change to form the Pfrstate. Herefrindicates that now not red but far-red (also called "near infra-red"; 705–740 nm) is differentially absorbed. This shift in absorbance is apparent to the human eye as a slightly more greenish color. When Pfrabsorbs far-red light it is converted back to Pr.Hence, red light makes Pfr,far-red light makes Pr.In plants at least Pfris the physiologically active or "signalling" state.

Phytochromes' effect on phototropism

[edit]Phytochromes also have the ability to sense light, which causes the plant to grow towards it. This is calledphototropism.[7]Janoudi and his fellow coworkers wanted to see what type of phytochrome was responsible for causing phototropism to occur, and performed a series of experiments. They found that blue light causes the plantArabidopsis thalianato exhibit a phototropic response; this curvature is heightened with the addition of red light.[7]They also found that five different phytochromes were present in the plant, while some mutants that did not function properly expressed a lack of phytochromes.[7]Two of these mutant variants were very important for this study: phyA-101 and phyB-1.[7]These are the mutants of phytochrome A and B respectively. The normally functional phytochrome A causes a sensitivity to far red light, and it causes a regulation in the expression of curvature toward the light, whereas phytochrome B is more sensitive to the red light.[7]

The experiment consisted in thewild-typeform of Arabidopsis, phyA-101(phytochrome A (phyA) null mutant), phyB-1 (phytochrome B deficient mutant).[7]They were then exposed to white light as a control blue and red light at different fluences of light, the curvature was measured.[7]It was determined that in order to achieve aphenotypeof that of the wild-type phyA-101 must be exposed to four orders of higher magnitude or about 100umol m−2fluence.[7]However, the fluence that causes phyB-1 to exhibit the same curvature as the wild-type is identical to that of the wild-type.[7]The phytochrome that expressed more than normal amounts of phytochrome A it was found that as the fluence increased the curvature also increased up to 10umol-m−2the curvature was similar to the wild-type.[7]The phytochrome expressing more than normal amounts of phytochrome B exhibited curvatures similar to that of the wild type at different fluences of red light up until the fluence of 100umol-m−2at fluences higher than this curvature was much higher than the wild-type.[7]

Thus, the experiment resulted in the finding that another phytochrome than just phytochrome A acts in influencing the curvature since the mutant is not that far off from the wild-type, and phyA is not expressed at all.[7]Thus leading to the conclusion that two phases must be responsible for phototropism. They determined that the response occurs at low fluences, and at high fluences.[7]This is because for phyA-101 the threshold for curvature occurred at higher fluences, but curvature also occurs at low fluence values.[7]Since the threshold of the mutant occurs at high fluence values it has been determined that phytochrome A is not responsible for curvature at high fluence values.[7]Since the mutant for phytochrome B exhibited a response similar to that of the wild-type, it had been concluded that phytochrome B is not needed for low or high fluence exposure enhancement.[7]It was predicted that the mutants that over expressed phytochrome A and B would be more sensitive. However, it is shown that an over expression of phy A does not really effect the curvature, thus there is enough of the phytochrome in the wild-type to achieve maximum curvature.[7]For the phytochrome B over expression mutant higher curvature than normal at higher fluences of light indicated that phy B controls curvature at high fluences.[7]Overall, they concluded that phytochrome A controls curvature at low fluences of light.[7]

Phytochrome effect on root growth

[edit]Phytochromes can also affect root growth. It has been well documented that gravitropism is the main tropism in roots. However, a recent study has shown that phototropism also plays a role. A red light induced positive phototropism has been recently recorded in an experiment that used Arabidopsis to test where in the plant had the most effect on a positive phototropic response. The experimenters utilized an apparatus that allowed forroot apexto be zero degrees so that gravitropism could not be a competing factor. When placed in red light, Arabidopsis roots displayed a curvature of 30 to 40 degrees. This showed a positive phototropic response in the red light. They then wanted to pinpoint exactly where in the plant light is received. When roots were covered there was little to no curvature of the roots when exposed to red light. In contrast, when shoots were covered, there was a positive phototropic response to the red light. This proves that lateral roots is where light sensing takes place. In order to further gather information regarding the phytochromes involved in this activity, phytochrome A, B, D and E mutants, and WT roots were exposed to red light. Phytochrome A and B mutants were severely impaired. There was no significant difference in the response ofphyDandphyEcompared with the wildtype, implying thatphyAandphyBare responsible for positive phototropism in roots.

Biochemistry

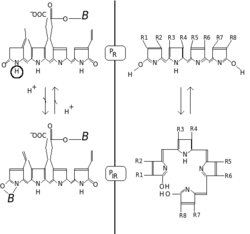

[edit]Chemically, phytochrome consists of achromophore,a single bilin molecule consisting of an open chain of fourpyrrolerings, covalently bonded to theproteinmoiety via highly conserved cysteine amino acid. It is the chromophore that absorbs light, and as a result changes the conformation of bilin and subsequently that of the attached protein, changing it from one state or isoform to the other.

The phytochrome chromophore is usuallyphytochromobilin,and is closely related tophycocyanobilin(the chromophore of thephycobiliproteinsused bycyanobacteriaandred algaeto capture light forphotosynthesis) and to thebilepigmentbilirubin(whose structure is also affected by light exposure, a fact exploited in thephototherapyofjaundicednewborns). The term "bili" in all these names refers to bile. Bilins are derived from the closed tetrapyrrole ring of haem by an oxidative reaction catalyzed by haem oxygenase to yield their characteristic open chain.Chlorophylland haem (Heme) share a common precursor in the form of Protoporphyrin IX, and share the same characteristic closed tetrapyrrole ring structure. In contrast to bilins, haem and chlorophyll carry a metal atom in the center of the ring, iron or magnesium, respectively.[8]

The Pfrstate passes on a signal to other biological systems in the cell, such as the mechanisms responsible forgeneexpression. Although this mechanism is almost certainly abiochemicalprocess, it is still the subject of much debate. It is known that although phytochromes are synthesized in thecytosoland the Prform is localized there, the Pfrform, when generated by light illumination, is translocated to thecell nucleus.This implies a role of phytochrome in controlling gene expression, and many genes are known to be regulated by phytochrome, but the exact mechanism has still to be fully discovered. It has been proposed that phytochrome, in the Pfrform, may act as akinase,and it has been demonstrated that phytochrome in the Pfrform can interact directly withtranscription factors.[9]

Discovery

[edit]The phytochrome pigment was discovered bySterling HendricksandHarry Borthwickat theUSDA-ARSBeltsville Agricultural Research CenterinMarylandduring a period from the late 1940s to the early 1960s. Using aspectrographbuilt from borrowed and war-surplus parts, they discovered that red light was very effective for promoting germination or triggering flowering responses. The red light responses were reversible by far-red light, indicating the presence of a photoreversible pigment.

The phytochrome pigment was identified using aspectrophotometerin 1959 by biophysicistWarren Butlerand biochemistHarold Siegelman.Butler was also responsible for the name, phytochrome.

In 1983 the laboratories of Peter Quail and Clark Lagarias reported the chemical purification of the intact phytochrome molecule, and in 1985 the first phytochromegene sequencewas published by Howard Hershey and Peter Quail. By 1989, molecular genetics and work withmonoclonal antibodiesthat more than one type of phytochrome existed; for example, thepeaplant was shown to have at least two phytochrome types (then called type I (found predominantly in dark-grown seedlings) and type II (predominant in green plants)). It is now known bygenome sequencingthatArabidopsishas five phytochrome genes (PHYA - E) but that rice has only three (PHYA - C). While this probably represents the condition in several di- and monocotyledonous plants, many plants arepolyploid.Hencemaize,for example, has six phytochromes - phyA1, phyA2, phyB1, phyB2, phyC1 and phyC2. While all these phytochromes have significantly different protein components, they all use phytochromobilin as their light-absorbing chromophore. Phytochrome A or phyA is rapidly degraded in the Pfr form - much more so than the other members of the family. In the late 1980s, the Vierstra lab showed that phyA is degraded by the ubiquitin system, the first natural target of the system to be identified in eukaryotes.

In 1996 David Kehoe and Arthur Grossman at the Carnegie Institution at Stanford University identified the proteins, in the filamentouscyanobacteriumFremyella diplosiphon called RcaE with similarly to plant phytochrome that controlled a red-green photoreversible response called chromatic acclimation and identified a gene in the sequenced, published genome of thecyanobacteriumSynechocystiswith closer similarity to those of plant phytochrome. This was the first evidence of phytochromes outside the plant kingdom. Jon Hughes in Berlin and Clark Lagarias at UC Davis subsequently showed that this Synechocystis gene indeed encoded abona fidephytochrome (named Cph1) in the sense that it is a red/far-red reversible chromoprotein. Presumably plant phytochromes are derived from an ancestral cyanobacterial phytochrome, perhaps by gene migration from thechloroplastto the nucleus. Subsequently, phytochromes have been found in otherprokaryotesincludingDeinococcus radioduransandAgrobacterium tumefaciens.InDeinococcusphytochrome regulates the production of light-protective pigments, however inSynechocystisandAgrobacteriumthe biological function of these pigments is still unknown.

In 2005, the Vierstra and Forest labs at theUniversity of Wisconsinpublished a three-dimensional structure of a truncatedDeinococcusphytochrome (PAS/GAF domains). This paper revealed that the protein chain forms a knot - a highly unusual structure for a protein. In 2008, two groups around Essen and Hughes in Germany and Yang and Moffat in the US published the three-dimensional structures of the entire photosensory domain. One structures was for theSynechocystis sp. (strain PCC 6803)phytochrome in Pr and the other one for thePseudomonas aeruginosaphytochrome in the Pfrstate. The structures showed that a conserved part of the PHY domain, the so-called PHY tongue, adopts different folds. In 2014 it was confirmed by Takala et al that the refolding occurs even for the same phytochrome (fromDeinococcus)as a function of illumination conditions.

Genetic engineering

[edit]Around 1989, several laboratories were successful in producingtransgenic plantswhich produced elevated amounts of different phytochromes (overexpression). In all cases the resulting plants had conspicuously short stems and dark green leaves. Harry Smith and co-workers at Leicester University in England showed that by increasing the expression level of phytochrome A (which responds to far-red light),shade avoidanceresponses can be altered.[10]As a result, plants can expend less energy on growing as tall as possible and have more resources for growing seeds and expanding their root systems. This could have many practical benefits: for example, grass blades that would grow more slowly than regular grass would not require mowing as frequently, or crop plants might transfer more energy to the grain instead of growing taller.

In 2002, the light-induced interaction between a plant phytochrome and phytochrome-interacting factor (PIF) was used to control gene transcription in yeast. This was the first example of using photoproteins from another organism for controlling a biochemical pathway.[11]

References

[edit]- ^PDB:3G6O;Yang X, Kuk J, Moffat K (2009)."Crystal structure of P. aeruginosa bacteriaphytochrome PaBphP photosensory core domain mutant Q188L".Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A.106(37): 15639–15644.doi:10.1073/pnas.0902178106.PMC2747172.PMID19720999.

- ^abLi J, Li G, Wang H, Wang Deng X (2011)."Phytochrome signaling mechanisms".The Arabidopsis Book.9:e0148.doi:10.1199/tab.0148.PMC3268501.PMID22303272.

- ^Halliday, Karen J.; Davis, Seth J. (2016)."Light-sensing phytochromes feel the heat"(PDF).Science.354(6314): 832–833.Bibcode:2016Sci...354..832H.doi:10.1126/science.aaj1918.PMID27856866.S2CID42594849.

- ^Sharrock R. A. (2008). The phytochrome red/far-red photoreceptor superfamily. Genome biology, 9(8), 230.doi:10.1186/gb-2008-9-8-230PMC2575506

- ^Britz SJ, Galston AW (Feb 1983)."Physiology of Movements in the Stems of Seedling Pisum sativum L. cv Alaska: III. Phototropism in Relation to Gravitropism, Nutation, and Growth".Plant Physiol.71(2): 313–318.doi:10.1104/pp.71.2.313.PMC1066031.PMID16662824.

- ^Walker TS, Bailey JL (Apr 1968)."Two spectrally different forms of the phytochrome chromophore extracted from etiolated oat seedlings".Biochem J.107(4): 603–605.doi:10.1042/bj1070603.PMC1198706.PMID5660640.

- ^abcdefghijklmnopqrsAbdul-kader, Janoudi (1977)."Multiple Phytochromes are Involved in Red-Light-Induced Enhancement of First-Positive Phototropism in Arabidopsis thaliana"(PDF).plantphysiol.org.

- ^Mauseth, James D. (2003).Botany: An Introduction to Plant Biology(3rd ed.). Sudbury, MA: Jones and Bartlett Learning. pp. 422–427.ISBN978-0-7637-2134-3.

- ^Shin, Ah-Young; Han, Yun-Jeong; Baek, Ayoung; Ahn, Taeho; Kim, Soo Young; Nguyen, Thai Son; Son, Minky; Lee, Keun Woo; Shen, Yu (2016-05-13)."Evidence that phytochrome functions as a protein kinase in plant light signalling".Nature Communications.7(1): 11545.Bibcode:2016NatCo...711545S.doi:10.1038/ncomms11545.ISSN2041-1723.PMC4869175.PMID27173885.

- ^Robson, P. R. H., McCormac, A. C., Irvine, A. S. & Smith, H. Genetic engineering of harvest index in tobacco through overexpression of a phytochrome gene. Nature Biotechnol. 14, 995–998 (1996).

- ^Shimizu-Sato S, Huq E, Tepperman JM, Quail PH (October 2002). "A light-switchable gene promoter system".Nature Biotechnology.20(10): 1041–4.doi:10.1038/nbt734.PMID12219076.S2CID24914960.

Sources

[edit]- Lia H, Zhangb J, Vierstra RD, Lia H (2010)."Quaternary organization of a phytochrome dimer as revealed by cryoelectron microscopy".PNAS.107(24): 10872–10877.Bibcode:2010PNAS..10710872L.doi:10.1073/pnas.1001908107.PMC2890762.PMID20534495.

- "Tripping the Light Switch Fantastic",by Jim De Quattro, 1991.

- "Nature’s Timekeeping",by Kit Smith, 2004.

- Terry and Gerry Audesirk.Biology: Life on Earth.

- Linda C Sage.A pigment of the imagination: a history of phytochrome research.Academic Press 1992.ISBN0-12-614445-1

- Gururani, Mayank Anand, Markkandan Ganesan, and Pill-Soon Song. "Photo-biotechnology as a tool to improve agronomic traits in crops."Biotechnology Advances(2014).