SMSStrassburg

SMSStrassburg

| |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | SMSStrassburg |

| Namesake | Strassburg |

| Builder | Kaiserliche WerftWilhelmshaven |

| Laid down | October 1910 |

| Launched | 24 August 1911 |

| Commissioned | 1 October 1912 |

| Fate | Ceded to Italy in 1920 |

| Name | Taranto |

| Acquired | 20 July 1920 |

| Commissioned | 2 June 1925 |

| Decommissioned | December 1942 |

| Fate | Sunk by air attack in 1944 |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type | Magdeburg-classcruiser |

| Displacement | |

| Length | 138.70 m (455 ft 1 in) |

| Beam | 13.50 m (44 ft 3 in) |

| Draft | 4.25 m (13 ft 11 in) |

| Installed power |

|

| Propulsion |

|

| Speed | 27.5knots(50.9 km/h; 31.6 mph) |

| Range | 5,820nmi(10,780 km; 6,700 mi) at 12 knots (22 km/h; 14 mph) |

| Complement |

|

| Armament |

|

| Armor |

|

SMSStrassburgwas alight cruiserof theMagdeburgclassin the GermanKaiserliche Marine(Imperial Navy). Her class included three other ships:Magdeburg,Breslau,andStralsund.Strassburgwas built at theKaiserliche Werftshipyard inWilhelmshavenfrom 1910 to October 1912, when she was commissioned into theHigh Seas Fleet.The ship was armed with a main battery of twelve10.5 cm (4.1 in) SK L/45 gunsand had a top speed of 27.5 knots (50.9 km/h; 31.6 mph).

Strassburgspent the first year of her service overseas, after which she was assigned to the reconnaissance forces of the High Seas Fleet. She saw significant action at theBattle of Heligoland Bightin August 1914 and participated in theraid on Scarborough, Hartlepool and Whitbyin December 1914. By 1916, the ship was transferred to the Baltic to operate against theRussian Navy.She saw action duringOperation Albionin theGulf of Rigain October 1917, including screening for thebattleshipsKönigandMarkgrafduring theBattle of Moon Sound.She returned to the North Sea for the planned final operation against the BritishGrand Fleetin the last weeks of the war, and was involved in themutiniesthat forced the cancellation of the operation.

The ship served briefly in the newReichsmarinein 1919 before being transferred to Italy as awar prize.She was formally transferred in July 1920 and renamedTarantofor service in theItalian Navy.In 1936–1937, she was rebuilt for colonial duties and additional anti-aircraft guns were installed. She saw no significant action duringWorld War IIuntil the Italian surrender, which ended Italy's participation in the war. She was scuttled by the Italian Navy, captured and raised by the Germans, and sunk by Allied bombers in October 1943. The Germans raised the ship again, which was sunk a second time by bombers in September 1944.Tarantowas finally broken up for scrap in 1946–1947.

Design

[edit]

TheMagdeburg-class cruiserswere designed in response to the development of the BritishInvincible-classbattlecruisers,which were faster than all existing German light cruisers. As a result, speed of the new ships must be increased. To accomplish this, more powerful engines were fitted and theirhullswere lengthened to improve their hydrodynamic efficiency. These changes increased top speed from 25.5 to 27knots(47.2 to 50.0 km/h; 29.3 to 31.1 mph) over the precedingKolberg-class cruisers.To save weight,longitudinal framingwas adopted for the first time in a major German warship design. In addition, theMagdeburgs were the first cruisers to carrybelt armor,which was necessitated by the adoption of more powerful 6-inch (150 mm) guns in the latest British cruisers.[1]

Strassburgwas 138.70 m (455 ft 1 in)long overalland had abeamof 13.50 m (44 ft 3 in) and adraftof 4.25 m (13 ft 11 in) forward. Shedisplaced4,564t(4,492long tons) normally and up to 5,281 t (5,198 long tons) atfull load.The ship had a shortforecastledeck and a minimalsuperstructurethat consisted primarily of aconning towerlocated on the forecastle. She was fitted with two polemastswith platforms forsearchlights.Strassburghad a crew of 18 officers and 336 enlisted men.[2]

Her propulsion system consisted of two sets of Marine-typesteam turbinesdriving twoscrew propellers.They were designed to give 25,000metric horsepower(18,390kW;24,660shp), but reached 33,482 PS (24,626 kW; 33,024 shp) in service. These were powered by sixteen coal-fired Marine-typewater-tube boilers,although they were later altered to usefuel oilthat was sprayed on the coal to increase its burn rate. The boilers were vented through fourfunnelslocatedamidships.These gave the ship a top speed of 27.5 knots (50.9 km/h; 31.6 mph).Strassburgcarried 1,200 t (1,181 long tons) of coal, and an additional 106 t (104 long tons) of oil that gave her a range of approximately 5,820nautical miles(10,780 km; 6,700 mi) at 12 knots (22 km/h; 14 mph).[2]

The ship was armed with amain batteryof twelve10.5 cm (4.1 in) SK L/45 gunsin single pedestal mounts. Two were placed side by side forward on the forecastle, eight were located on thebroadside,four on either side, and two were side by side aft. The guns had a maximum elevation of 30 degrees, which allowed them to engage targets out to 12,700 m (13,900 yd).[3]They were supplied with 1,800 rounds of ammunition, for 150 shells per gun. She was also equipped with a pair of 50 cm (19.7 in)torpedo tubeswith fivetorpedoes;the tubes were submerged in the hull on thebroadside.She could also carry 120mines.In 1915,Strassburgwas completely rearmed, replacing the 10.5 cm guns with seven15 cm (5.9 in) SK L/45 guns,two8.8 cm (3.5 in) SK L/45 guns,and two deck-mounted 50 cm torpedo tubes.[4]

Strassburgwas protected by a waterlinearmor beltand a curved armor deck. The deck was flat across most of the hull, but angled downward at the sides and connected to the bottom edge of the belt. The belt and deck were both 60 mm (2.4 in) thick. The conning tower had 100 mm (3.9 in) thick sides.[4][5]

Service history

[edit]

Strassburgwas ordered under the contract nameErsatzCondorand waslaid downat theKaiserliche Werft(Imperial Shipyard) inWilhelmshavenin October 1910 andlaunchedon 24 August 1911, andRudolf Schwander,the major ofher namesake city,gave a speech at her launching ceremony. After her launching,fitting-outwork commenced, including the installation of her engines, which were the first set of turbines designed by theKaiserliche Werft.She wascommissionedinto active service on 1 October 1912 under the command ofFregattenkapitän(FK—Frigate Captain)Wilhelm Tägert.After completing initialsea trials,she was assigned to the Reconnaissance Unit on 23 December, taking the place of the older cruiserBerlin.At that time, Tägert was replaced by FK Wilhelm Paschen. On 6 January,Strassburgwas accidentally rammed by the Danish steamerChristian IX,which was passing through the wrong side of the canal entrance. This delayedStrassburg's arrival for training exercises with the rest of her unit until 23 February.[2][6]

Strassburgspent the first year of service overseas, from 1913 to 1914.[7]She was first sent abroad on 6 April, when she sailed in company with the light cruiserDresdenfor theMediterranean Sea.She arrived inValletta,Malta,on 13 April, where she joined theMediterranean Division,commanded byKonteradmiral(Rear Admiral)Konrad Trummleraboard the battlecruiserGoeben.From there,Strassburgsteamed to visitAlexandrettain theOttoman Empire,followed by a stop inConstantinople,the Ottoman capital, in early May. By early June, she had entered theAdriatic Seaand stopped inVeniceandNaples,Italy, andPolain theAustro-Hungarian Empire.Later in June, the ship moved to theAegean Seaand later cruised in the eastern Mediterranean, including off the coast ofOttoman Syria.Having stopped in Alexandretta again in early September,Strassburggot underway to return to Germany on 9 September. She arrived in Kiel two weeks later, anchoring in the harbor on 23 September.[8]

She was thendry dockedfor an overhaul after her voyage abroad, during which FKHeinrich Retzmannrelieved Paschen. The work was completed by 8 December, when she was selected to participate in a long-distance cruise to test the reliability of the new turbine propulsion system in the battleshipsKaiserandKönig Albert.The three ships were organized in a special "Detached Division", under the command ofKonteradmiralHubert von Rebeur-Paschwitz.Strassburggot underway on 8 December and met the two battleships at sea the following day; they proceeded to the German colonies in western Africa by way of theCanary Islands.The ships visitedLoméinTogoland,Dualaand Victoria inKamerun,andSwakopmundinGerman South-West Africa.They then sailed south toCape TowninBritish South Africa.From there, the ships sailed toSt. Helenain the South Atlantic and then on toRio de Janeiro,arriving on 15 February 1914. Rebeur-Paschwitz came aboardStrassburg,which was detached to visitBuenos Aires,Argentina for an official visit. While there, Rebeur-Paschwitz fell ill and had to go ashore to be hospitalized, soStrassburgdeparted without him on 12 March to meet the two battleships inMontevideo,Uruguay. After Rebeur-Paschwitz returned from the hospital, the three ships sailed south aroundCape Hornand then north toValparaiso,Chile, arriving on 2 April and remaining for over a week.[6][9]

On 11 April, the ships departed Valparaiso for the long journey back to Germany. On the return trip, the ships visited several more ports, includingBahía Blanca,Argentina, before returning to Rio de Janeiro. On 16 May, the two battleships left Rio de Janeiro for the Atlantic leg of the journey to sail directly back to Germany; they arrived in Kiel on 17 June 1914.Strassburgwas detached to proceed independently, by way of theWest Indies.She assisted the German steamerMecklenburg,which had run aground in the area, and then proceeded to the Dominican Republic to pressure the Dominican government over a disagreement with Germany. In the course of the voyage, the ships traveled some 20,000 nautical miles (37,000 km; 23,000 mi). She was anchored atSaint Thomason 20 July when she received orders to return home. She reachedHortain theAzoreson 27 July, and the next day sailed at top speed to pass through theEnglish Channelwith her lights dimmed owing to theJuly Crisisthat threatened to instigate a major war in Europe.Strassburgarrived in Wilhelmshaven on 1 August, the day the German militarymobilizedat the start ofWorld War I.[8][10]

World War I

[edit]1914

[edit]

StrassburgjoinedII Scouting Groupat the start of the conflict. Late on 17 August, some two weeks after the outbreak of World War I,StrassburgandStralsundsortied to conduct a sweep into theHoofdento search for British reconnaissance forces. They were accompanied by theU-boatsU-19andU-24,which were to ambush any British forces that counter-attacked. Early the following morning,Strassburgspotted a pair of Britishsubmarines,HMSE5andE7.She opened fire on the submarines, but they submerged before she scored any hits. The two cruisers then encountered a group of sixteen Britishdestroyersand a light cruiser at a distance of about 10,000 m (33,000 ft). Significantly outnumbered, the two German cruisers broke contact and returned to port.[11][12]Strassburgjoined the cruiserRostockfor another sweep on 21–22 August to sink Britishfishing trawlerin theDogger Bankarea.[8]

Strassburgwas heavily engaged at theBattle of Heligoland Bightless than two weeks later, on 28 August. British battlecruisers andlight cruisersraided the German reconnaissance screen commanded byRear AdmiralLeberecht Maassin theHeligoland Bight.Strassburgwas at that time moored in Wilhelmshaven, and she was the first German cruiser to leave port to reinforce the German reconnaissance forces, departing at 09:10. She was joined soon thereafter by the light cruiserCölnat 09:30; they were ordered to pursue the British light forces that had by then begun withdrawing. At 11:00, she encountered the badly damaged British cruiserHMSArethusa,which had been hit several times byStettinandFrauenlob.StrassburgattackedArethusa,but was driven off by the 1st Destroyer Flotilla. She lost contact with the British in the mist, but located them again after 13:10 from the sound of British gunfire that destroyed the cruiserMainz.Along withCöln,she badly damaged three British destroyers—Laertes,Laurel,andLiberty—before being driven off again. In return,Strassburgwas hit by a single 6-inch (152 mm) shell that struck above her belt armor and exploded, but did little damage. Shortly thereafter, the British battlecruisers intervened and sankAriadneand Maass'sflagshipCöln.AsStrassburgwithdrew, she had a close encounter with the British battlecruisers, but the British mistook her for one of their own cruisers in the hazy conditions.Strassburgand the rest of the surviving light cruisers retreated into the haze and were reinforced by the battlecruisers ofI Scouting Group.[13][14]

In early September,Strassburgmoved to theBaltic Seafor an operation in company with the large armored cruiserBlücherthat lasted from 3 to 6 September. She then returned to operations in the North Sea, and she participated in theraid on Yarmouthon 2–3 November. The ships of II Scouting Group carried out another sweep into the North Sea on 10 December that failed to locate any British forces.[8]Strassburgwas present during theraid on Scarborough, Hartlepool and Whitbyon 15–16 December, as part of the screening force for the battlecruisers of Rear AdmiralFranz von Hipper's I Scouting Group. After completing the bombardment of the towns, the Germans began to withdraw, though British forces moved to intercept them.Strassburg,two of the other screening cruisers, and two flotillas oftorpedo boatssteamed between two British squadrons. In the heavy mist, which reduced visibility to less than 4,000 yd (3,700 m), only her sister shipStralsundwas spotted, though only briefly. The Germans were able to use the bad weather to cover their withdrawal.[15]

1915–1916

[edit]Strassburgcovered a minelaying operation off theAmrun Bankon 3 January 1915, followed by another in company withStralsundon 14 January off theHumber.Two days later, she was dry docked at Wilhelmshaven for periodic maintenance, and so she was not present for the operation that resulted in theBattle of Dogger Bankon 24 January. Work on the ship was completed by 31 January. The ships of II Scouting Group were sent to the Baltic on 17 March for an operation in the area ofÅlandthat lasted from 21 to 24 March. By 9 April,Strassburgand the other cruisers had returned to the North Sea.Strassburgcovered a mine-laying operation off theSwarte Bankon 17–18 April, and another off the Dogger Bank on 17–18 May. She joined the rest of the High Seas Fleet for a sweep into the North Sea on 29–30 May, which ended without encountering British vessels. She next participated in two patrols to inspect fishing boats offTerschellingandHorns Revon 28 June and 2 July, respectively.[16]

On 14 July,Strassburgwas dry docked at theKaiserliche WerftinKielto be rearmed with 15 cm guns; she was the first German light cruiser to be so rearmed. Work lasted until 18 October, and she also received a pair of 50 cm torpedo tubes on her main deck during the refit. Two days later, the ship arrived back in the North Sea and rejoined II Scouting Group. Shortly thereafter, she sortied for another fleet sweep into the North Sea on 23–24 October.Strassburgand the rest of II Scouting Group patrolled theSkagerrakandKattegatfor enemy merchant shipping from 16 to 18 December. That month, Retzmann left the ship, being replaced by FK von Schlick. Another fleet sweep toward the Hoofden took place from 5 to 7 March 1916.[17]

On 18 March,Strassburgwas transferred toVI Scouting Group,which was based in the Baltic and operated in the naval campaign against Russian forces. Beginning in April, she was occupied with a series of minelaying operations in theGulf of Finland.The ship next participated in a pair of sweeps towardBogskäron 17–18 July and 16–17 August. The rest of 1916 passed uneventfully forStrassburgat Libau. She departed from that port on 17 January 1917 for an overhaul period at theAG Wesershipyard inBremen.The work lasted nearly three months, and she arrived back in Libau on 7 April. She participated in four minelaying operations later that month.[18]

Operation Albion

[edit]

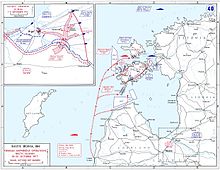

Strassburgand the rest of VI Scouting Group next saw action duringOperation Albionagainst the Russian naval forces in theGulf of Rigain October. While preparations for the operation were underway in September, Schlick was temporarily transferred to command the transport fleet, as he had prior experience with naval logistics.Strassburg'sexecutive officer,FKHans Quaet-Faslem,temporarily took command of the ship.[17]At 06:00 on 14 October 1917,Strassburg,Kolberg,andAugsburgleftLibauto escort minesweeping operations in the Gulf of Riga. They were attacked by Russian 12-inch (305 mm) coastal guns on their approach and were temporarily forced to turn away. By 08:45, however, they had anchored off theMikailovsk Bankand the minesweepers began to clear a path in the minefields.[19]

Two days later,StrassburgandKolbergjoined thedreadnoughtsKönigandKronprinzfor a sweep of the Gulf of Riga. In the ensuingBattle of Moon Soundthat began on the morning of 17 October, the battleships destroyed the oldpre-dreadnoughtSlavaand forced the pre-dreadnoughtGrazhdaninto leave the Gulf. On 21 October,Strassburgand the battleshipMarkgrafwere tasked with assaulting the island ofKyno.The two ships bombarded the island;Strassburgexpended approximately 55 rounds on the port ofSalismünde.Four days later, she bombarded Salismünde, Kyno, andHainaschagain.[18][20]

On 31 October,Strassburgcarried GeneralAdolf von Seckendorff,the first military governor of the captured islands, from Libau toArensburg.The following day, she embarked GeneralHugo von Kathen,the commander of the landing force, along with his staff to be carried back to Libau. In November, Schlick returned to command of the cruiser, though later that month he was replaced by FK Paul Reichardt.[17]

End of the war

[edit]With the strategic situation in the Baltic altered significantly in Germany's favor by the end of 1917, much of its naval forces could be withdrawn. On 14 December,Strassburgleft Libau for Kiel for periodic maintenance, during which some consideration was given to converting the ship into anaircraft carrier,though this was not carried out. While work was still underway, the ship was assigned to the High Seas Fleet, and on 4 April, she arrived at her new unit,IV Scouting Group.The unit was led byKommodoreJohannes von Karpfaboard his flagship, the cruiserRegensburg.Strassburgnext participated in the fleet operation on 23–24 April.[18]This operation envisioned intercepting one of theconvoysbetween Britain and Norway, which were being escorted by detached squadrons of the BritishGrand Fleet.The operation was cancelled after the battlecruiserMoltkeslipped one of her propellers, temporarily leaving her dead in the water.Strassburgwas the nearest vessel, and was first to come alongside and attempt to take her under tow. Her towline broke, and the battleshipOldenburgtook over the tow.Strassburgremained with the ships as an escort during their return to port, only returning to the main body of the fleet later. In any event, German intelligence had failed to correctly identify when the next convoy sailed, and the High Seas Fleet returned to port empty-handed.[18][21]

Strassburgtook part in several minelaying operations in the North Sea in May and June. In August, she and the rest of IV Scouting Group were assigned to the naval component ofOperation Schlußstein,a planned amphibious assault onSt Petersburg,Russia. The ships, led byStralsund,moved to Libau on 18 August, and then proceeded on to Finland, stopping inHelsingforsand thenKoivisto.From there, they sailed forReval.The ships alternated at Koivisto, patrolling to guard the German forces during preparations for the attack.Strassburgremained at Koivisto from 9 to 17 September, returning thereafter to Reval. The operation was cancelled soon thereafter, andStrassburgreturned to the North Sea, passing throughTurku,Mariehamn,Reval, and Libau before arriving on 1 October.[18]

In late October,Strassburgwas to participate in afinal, climactic attackby the High Seas Fleet. AdmiralsReinhard Scheerand Hipper intended to inflict as much damage as possible on the British navy, in order to secure a better bargaining position for Germany, whatever the cost to the fleet.[22]On the morning of 27 October, days before the operation was scheduled to begin, around 45 crew members fromStrassburg's engine room slipped over the side of the ship and went into Wilhelmshaven. The crewmen had to be rounded up and returned to the ship, after which the IV Scouting Group moved toCuxhaven.Here, men from all six cruisers in the unit refused to work in protest of the war, and in support of thearmisticeproposed byPrince Maximilian.On the morning of 29 October 1918, the order was given to sail from Wilhelmshaven the following day. Starting on the night of 29 October, sailors onThüringenand then on several other battleshipsmutinied.The unrest ultimately forced Hipper and Scheer to cancel the operation.[23][22]

In an attempt to suppress the unrest, the fleet was dispersed, andStrassburgwas sent to Cuxhaven on 30 October. From there, they moved to Kiel in early November, andStrassburgwas sent toSonderburg,north of Kiel. From there, the ships were moved again, this time toSassnitzon 11 November.[18]Strassburgwas joined by the cruiserBrummerin Sassnitz. There, the commander ofStrassburgtook command of the naval forces in the port and invited a sailor's council to be formed to assist in controlling the forces there.[24]Thearmistice that ended the wartook effect that day, andStrassburgwas disarmed there in accordance with Germany's surrender. Her crew was also reduced at that time. She was not included in the list of ships that were interned atScapa Flow.On 20 March 1919, the ship received a full crew, and she became the flagship of the Minesweeping Unit of the Black Sea, an organization created on 24 March to clear the numerous minefields laid by German and Russian forces in the Baltic. This service continued for a year, until theKapp Putschof March 1920. After the war, Germany hoped to retainStrassburgfor further service in the reorganizedReichsmarine,but the Allies demanded the vessel be surrendered as a replacement for the ships that had been sunk in thescuttling of the German fleet in Scapa Flow.On 17 March, the German naval command issued an order striking the ship from thenaval register,to be effective as soon as she was decommissioned, which took place on 4 June.[25]

Italian service

[edit]Strassburgwas ceded to Italy as awar prize,and she departed Germany on 14 July in company with three other cruisers and four torpedo boats. They arrived in France on 19–20 July. She was transferred under the name "O" on 20 July in the French port ofCherbourg.[26][27]Strassburgwas commissioned into the ItalianRegia Marina(Royal Navy) on 2 June 1925 and her name was changed toTaranto,initially classed as a scout. Her two 8.8 cm anti-aircraft guns were replaced with two Italian 3-inch /40 anti-aircraft guns.[28][29]Her refit took longer to complete than any of the other ex-German or ex-Austro-Hungarian cruisers Italy received after the war, and she did not return to active service until June 1925.[30]She also had her superfiring 15 cm gun moved amidships, but in 1926 it was moved back to clear room for a platform to hold a scout plane. She initially carried aMacchi M.7flying boat,which was later replaced by aCANT 25ARflying boat.[31]

From May 1926,Tarantowas deployed to theRed Seato patrolItalian East Africa,where she served as the flagship of the colonial flotilla there. She remained there until January 1927.Tarantowas reclassified as a cruiser on 19 July 1929, and that year she joined the other two ex-German cruisers,AnconaandBariand the ex-German destroyerPremudaas the Scout Division of the 1st Squadron, based inLa Spezia.In 1931, her M.7 seaplane was replaced with the CANT 24AR seaplane. Another tour in East Africa followed from September 1935 to 1936. After returning to Italy, she underwent a refit that involved removing her forward two boilers and the funnel that vented them. This reduced her power to 13,000 shp (9,700 kW) and top speed to 21 kn (39 km/h; 24 mph),[29][32]though byWorld War IIonly 18 knots (33 km/h; 21 mph) could be maintained. Eight 20 mm (0.79 in) /65 and ten13.2 mm (0.52 in) machine gunswere added for close-range anti-aircraft defense.[28]

In 1940, after Italy formally entered the war,TarantoandBariwere only suitable for secondary roles; as a result, they were stationed in the Adriatic at Taranto. There, they carried out mining operations and coastal bombardments.[33]In early July 1940,Taranto,theauxiliary cruiserBarletta,the minelayerVieste,and the destroyersCarlo MirabelloandAugusto Ribotylaid a series of minefields in the Gulf of Taranto and in the southern Adriatic, totaling 2,335 mines.[34]She was thereafter assigned to theForza Navale Speciale(Special Naval Force) along with the other ex-German cruiser still in Italian service,Bari.TheFNSwas slated to take part in an amphibious invasion of the British island of Malta in 1942, but the operation was cancelled.[29]

Tarantowas transferred to Livorno on 26 February and reduced to atraining ship.[35]The navy made plans to convert bothTarantoandBariinto anti-aircraft cruisers in 1943, but the plans came to nothing.[33]She was decommissioned in December 1942 in La Spezia and was scuttled there on 9 September 1943 a day after thearmistice that ended the war for Italywas declared to prevent her from being seized by the Germans, who rapidly moved to occupy the country after Italy surrendered. The Germans captured the ship and re-floated her, though she was sunk by Allied bombers on 23 October. The Germans re-floated the ship again, and again she was sunk by bombers, on 23 September 1944 in the outer La Speziaroadstead,where the Germans had moved the hulk to block one of the entrances to theGulf of La Spezia.Tarantowas ultimately raised and broken up for scrap in 1946–1947.[28][29]

Footnotes

[edit]- ^Dodson & Nottelmann,pp. 137–138.

- ^abcGröner,pp. 107–108.

- ^Campbell & Sieche,pp. 140, 159.

- ^abGröner,p. 107.

- ^Campbell & Sieche,p. 159.

- ^abHildebrand, Röhr, & Steinmetz,pp. 205–206.

- ^Gröner,p. 108.

- ^abcdHildebrand, Röhr, & Steinmetz,p. 206.

- ^Staff 2010,pp. 10–11.

- ^Staff 2010,p. 11.

- ^Scheer,p. 42.

- ^Staff 2011,pp. 2–3.

- ^Bennett,pp. 145–150.

- ^Staff 2011,pp. 11, 13–16, 24.

- ^Tarrant,pp. 31, 34.

- ^Hildebrand, Röhr, & Steinmetz,pp. 206–207.

- ^abcHildebrand, Röhr, & Steinmetz,pp. 205, 207.

- ^abcdefHildebrand, Röhr, & Steinmetz,p. 207.

- ^Staff 2008,pp. 4, 60.

- ^Staff 2008,pp. 102–103, 113–114, 145–147.

- ^Massie,pp. 747–748.

- ^abTarrant,pp. 280–282.

- ^Woodward,pp. 118–119.

- ^Woodward,p. 167.

- ^Hildebrand, Röhr, & Steinmetz,pp. 207–208.

- ^Hildebrand, Röhr, & Steinmetz,p. 208.

- ^Dodson & Cant,p. 45.

- ^abcFraccaroli,p. 264.

- ^abcdBrescia,p. 105.

- ^Dodson & Cant,pp. 61–62.

- ^Dodson,p. 153.

- ^Dodson,pp. 153–154.

- ^abDodson & Cant,p. 63.

- ^Rohwer,p. 26.

- ^Dodson,pp. 154–155.

References

[edit]- Bennett, Geoffrey(2005).Naval Battles of the First World War.Barnsley: Pen & Sword Military Classics.ISBN978-1-84415-300-8.

- Brescia, Maurizio (2012).Mussolini's Navy: A Reference Guide to the Regia Marina 1930–1945.Barnsley: Seaforth.ISBN978-1-84832-115-1.

- Campbell, N. J. M. & Sieche, Erwin (1986). "Germany". In Gardiner, Robert & Gray, Randal (eds.).Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1906–1921.London: Conway Maritime Press. pp. 134–189.ISBN978-0-85177-245-5.

- Dodson, Aidan(2017). "After the Kaiser: The Imperial German Navy's Light Cruisers after 1918". In Jordan, John (ed.).Warship 2017.London: Conway. pp. 140–159.ISBN978-1-8448-6472-0.

- Dodson, Aidan; Cant, Serena (2020).Spoils of War: The Fate of Enemy Fleets after the Two World Wars.Barnsley: Seaforth Publishing.ISBN978-1-5267-4198-1.

- Dodson, Aidan;Nottelmann, Dirk (2021).The Kaiser's Cruisers 1871–1918.Annapolis: Naval Institute Press.ISBN978-1-68247-745-8.

- Fraccaroli, Aldo (1986). "Italy". In Gardiner, Robert & Gray, Randal (eds.).Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1906–1921.London: Conway Maritime Press. pp. 252–290.ISBN978-0-85177-245-5.

- Gröner, Erich(1990).German Warships: 1815–1945.Vol. I: Major Surface Vessels. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press.ISBN978-0-87021-790-6.

- Hildebrand, Hans H.; Röhr, Albert & Steinmetz, Hans-Otto (1993).Die Deutschen Kriegsschiffe: Biographien – ein Spiegel der Marinegeschichte von 1815 bis zur Gegenwart[The German Warships: Biographies − A Reflection of Naval History from 1815 to the Present] (in German). Vol. 7. Ratingen: Mundus Verlag.OCLC310653560.

- Massie, Robert K.(2003).Castles of Steel: Britain, Germany, and the Winning of the Great War at Sea.New York City: Ballantine Books.ISBN978-0-345-40878-5.

- Rohwer, Jürgen (2005).Chronology of the War at Sea 1939–1945 – The Naval History of World War Two.London: Chatham Publishing.ISBN978-1-59114-119-8.

- Scheer, Reinhard(1920).Germany's High Seas Fleet in the World War.London: Cassell and Company.OCLC52608141.

- Staff, Gary (2008).Battle for the Baltic Islands.Barnsley: Pen & Sword Maritime.ISBN978-1-84415-787-7.

- Staff, Gary (2010).German Battleships: 1914–1918 (Volume 2).Oxford: Osprey Books.ISBN978-1-84603-468-8.

- Staff, Gary (2011).Battle on the Seven Seas: German Cruiser Battles, 1914–1918.Barnsley: Pen & Sword Maritime.ISBN978-1-84884-182-6.

- Tarrant, V. E. (1995).Jutland: The German Perspective.London: Cassell Military Paperbacks.ISBN978-0-304-35848-9.

- Woodward, David (1973).The Collapse of Power: Mutiny in the High Seas Fleet.London: Arthur Barker Ltd.ISBN978-0-213-16431-7.

External links

[edit]- TarantoMarina Militare website

- Magdeburg-class cruisers

- Ships built in Wilhelmshaven

- 1911 ships

- World War I cruisers of Germany

- World War II shipwrecks in the Mediterranean Sea

- Maritime incidents in September 1943

- Maritime incidents in October 1943

- Cruisers sunk by aircraft

- Maritime incidents in September 1944

- Scuttled vessels

- Cruisers of the Regia Marina