Utrecht

Utrecht

Ut(e)reg(Utrechts) | |

|---|---|

Jaarbeursplein Uithof centre inUtrecht Science Park Spoorwegmuseum Neude | |

|

| |

| Nickname: Domstad (Cathedral City) | |

Location of Utrecht municipality | |

| Coordinates:52°05′27″N05°07′18″E/ 52.09083°N 5.12167°E | |

| Country | Netherlands |

| Province | Utrecht |

| Government | |

| • Body | Municipal council |

| •Mayor | Sharon Dijksma(PvdA) |

| Area | |

| • Municipality | 99.21 km2(38.31 sq mi) |

| • Land | 93.83 km2(36.23 sq mi) |

| • Water | 5.38 km2(2.08 sq mi) |

| •Randstad | 3,043 km2(1,175 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 5 m (16 ft) |

| Population | |

| • Municipality | 374,411 |

| • Density | 3,646/km2(9,440/sq mi) |

| •Urban | 489,734 |

| •Metro | 656,342 |

| •Randstad | 6,979,500 |

| Demonym | Utrechter(s)[nb 1] |

| Time zone | UTC+1(CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2(CEST) |

| Postcode | 3450–3455, 3500–3585 |

| Area code | 030 |

| Website | www |

| |

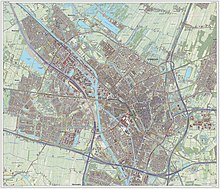

| Click on the map for a fullscreen view | |

Utrecht(/ˈjuːtrɛkt/YOO-trekt,[6][7]Dutch:[ˈytrɛxt],Utrecht dialect:Ut(e)reg[ˈytəʁɛχ]) is thefourth-largest cityof theNetherlands,as well as the capital and the most populous city of theprovinceofUtrecht.Themunicipalityof Utrecht is located in the eastern part of theRandstadconurbation,in the very centre of mainland Netherlands, and includesHaarzuilens,VleutenandDe Meern.It has a population of 361,699 as of December 2021[update].[8]

Utrecht's ancient city centre features many buildings and structures, several dating as far back as theHigh Middle Ages.It has been the religious centre of the Netherlands since the 8th century. In 1579, theUnion of Utrechtwas signed in the city to lay the foundations for theDutch Republic.Utrecht was the most important city in the Netherlands until theDutch Golden Age,when it was surpassed byAmsterdamas the country's cultural centre and most populous city.

Utrecht is home toUtrecht University,the largest university in the Netherlands, as well as several other institutions of higher education. Due to its central position within the country, it is an important hub for bothrailandroad transport;it has the busiest train station in the Netherlands,Utrecht Centraal.It has the second-highest number of cultural events in the Netherlands, after Amsterdam.[9]In 2012,Lonely Planetincluded Utrecht in the top 10 of the world's unsung places.[10]

History[edit]

Origins (before 650 CE)[edit]

Although there is some evidence of earlier inhabitation in the region of Utrecht, dating back to theStone Age(app. 2200BCE) and settling in theBronze Age(app. 1800–800 BCE),[11]the founding date of the city is usually related to the construction of aRomanfortification(castellum), probably built in around 50CE.A series of such fortresses were built after theRoman emperorClaudiusdecided the empire should not expand further north. To consolidate the border, theLimes Germanicusdefense line was constructed[12]along the main branch of the riverRhine,which at that time traversed a more northern route (now known as theKromme Rijn) compared to today's Rhine flow. These fortresses were designed to house acohortof about 500 Roman soldiers. Near the fort, settlements grew that housedartisans,traders and soldiers' wives and children.

In Roman times, the name of the Utrecht fortress was simplyTraiectum,denoting its location at a possible Rhine crossing. Traiectum became Dutch Trecht; with the U fromOld Dutch"uut" (downriver) added to distinguish U-trecht fromMaas-tricht,[13][14]on the riverMeuse.In 11th-century official documents, it was Latinized as Ultra Traiectum. Around the year 200, the wooden walls of the fortification were replaced by sturdiertuffstone walls,[15]remnants of which are still to be found below the buildings around Dom Square.

From the middle of the 3rd century,Germanic tribesregularly invaded the Roman territories. After around 275 the Romans could no longer maintain the northern border, and Utrecht was abandoned.[12]Little is known about the period from 270 to 650. Utrecht is first spoken of again several centuries after the Romans left. Under the influence of the growing realms of theFranks,duringDagobert I's reign in the 7th century, a church was built within the walls of the Roman fortress.[12]In ongoing border conflicts with theFrisians,this first church was destroyed.

Centre of Christianity in the Netherlands (650–1579)[edit]

By the mid-7th century, British, English and Irishmissionariesset out to convert theFrisians.Pope Sergius Iappointed their leader, SaintWillibrordus,as bishop of the Frisians. The tenure of Willibrordus is generally considered to be the beginning of theBishopric of Utrecht.[12]In 723, the Frankish leaderCharles Martelbestowed the fortress in Utrecht and the surrounding lands as the base of the bishops. From then on Utrecht became one of the most influential seats of power for the Catholic Church in the Netherlands. The archbishops of Utrecht were based at the uneasy northern border of theCarolingian Empire.In addition, the city of Utrecht had competition from the nearby trading centreDorestad.[12]After the fall of Dorestad around 850, Utrecht became one of the most important cities in the Netherlands.[16]The importance of Utrecht as a centre of Christianity is illustrated by the election of the Utrecht-bornAdriaan Florenszoon Boeyensaspopein 1522 (the last non-Italian pope beforeJohn Paul II).

Prince-bishops[edit]

When the Frankish rulers established the system offeudalism,theBishopsof Utrecht came to exercise worldly power asprince-bishops.[12]The territory of the bishopric not only included the modern province of Utrecht (Nedersticht, 'lowerSticht'), but also extended to the northeast. The feudal conflict of theMiddle Agesheavily affected Utrecht. The prince-bishopric was involved in almost continuous conflicts with the Counts ofHollandand the Dukes ofGuelders.[17]TheVeluweregion was seized by Guelders, but large areas in the modern province ofOverijsselremained as the Oversticht.

Religious buildings[edit]

Several churches and monasteries were built inside, or close to, the city of Utrecht. The most dominant of these was theCathedral of Saint Martin,inside the old Roman fortress. The construction of the presentGothicbuilding was begun in 1254 after an earlierromanesqueconstruction had been badly damaged by fire. Thechoirandtranseptwere finished from 1320 and were followed then by the ambitiousDom tower.[12]The last part to be constructed was the centralnave,from 1420. By that time, however, the age of the great cathedrals had come to an end and declining finances prevented the ambitious project from being finished, the construction of the central nave being suspended before the plannedflying buttressescould be finished.[12] Besides the cathedral there were fourcollegiate churchesin Utrecht:St. Salvator's Church(demolished in the 16th century), on the Dom square, dating back to the early 8th century.[18]SaintJohn(Janskerk), originating in 1040;[19]Saint Peter,building started in 1039[20]andSaint Mary's church building started around 1090 (demolished in the early 19th century, cloister survives).[21] Besides these churches, the city housedSt. Paul's Abbey,[22]the 15th-centurybeguinage of St. Nicholas,and a 14th-century chapter house of theTeutonic Knights.[23]

Besides these buildings which belonged to the bishopric, an additional fourparish churcheswere constructed in the city: theJacobikerk(dedicated to Saint James), founded in the 11th century, with the current Gothic church dating back to the 14th century;[24]the Buurkerk (Neighbourhood-church) of the 11th-century parish in the centre of the city; Nicolaichurch (dedicated toSaint Nicholas), from the 12th century,[25]and the 13th-century Geertekerk (dedicated to SaintGertrude of Nivelles).[26]

City of Utrecht[edit]

Its location on the banks of the river Rhine allowed Utrecht to become an important trade centre in the Northern Netherlands. The growing town was grantedcity rightsbyHenry Vat Utrecht on 2 June 1122. When the main flow of the Rhine moved south, the old bed which still flowed through the heart of the town became ever morecanalized;and the wharf system was built as an inner city harbour system.[27]On the wharfs, storage facilities (werfkelders) were built, on top of which the main street, including houses, was constructed. The wharfs and the cellars are accessible from a platform at water level with stairs descending from the street level to form a unique structure.[nb 2][28]The relations between the bishop, who controlled many lands outside of the city, and the citizens of Utrecht was not always easy.[12]The bishop, for example dammed theKromme RijnatWijk bij Duurstedeto protect his estates from flooding. This threatened shipping for the city and led the city of Utrecht to commission a canal to ensure access to the town for shipping trade: the Vaartse Rijn, connecting Utrecht to theHollandse IJsselatIJsselstein.

The end of independence[edit]

In 1528 the bishop lost secular power over both Neder- and Oversticht—which included the city of Utrecht—toCharles V, Holy Roman Emperor.Charles V combined theSeventeen Provinces(the currentBeneluxand the northern parts of France) as a personal union. This ended the prince-bishopric of Utrecht, as the secular rule was now thelordship of Utrecht,with the religious power remaining with the bishop, although Charles V had gained the right to appoint new bishops. In 1559 the bishopric of Utrecht was raised to archbishopric to make it the religious centre of the Northernecclesiastical provincein the Seventeen Provinces.

The transition from independence to a relatively minor part of a larger union was not easily accepted. To quell uprisings, Charles V struggled to exert his power over the city's citizens who had struggled to gain a certain level of independence from the bishops and were not willing to cede this to their new lord. The heavily fortified castleVredenburgwas built to house a large garrison whose main task was to maintain control over the city. The castle would last less than 50 years before it was demolished in an uprising in the early stages of theDutch Revolt.

Republic of the Netherlands (1579–1806)[edit]

In 1579 the northern seven provinces signed theUnion of Utrechttreaty (Dutch: Unie van Utrecht), in which they decided to join forces against Spanish rule. The Union of Utrecht is seen as the beginning of theDutch Republic.In 1580, the new and predominantly Protestant state abolished the bishoprics, including the archbishopric of Utrecht. Thestadtholdersdisapproved of the independent course of the Utrecht bourgeoisie and brought the city under much more direct control of the republic, shifting the power towards its dominant provinceHolland.This was the start of a long period of stagnation of trade and development in Utrecht. Utrecht remained an atypical city in the new republic being about 40% Catholic in the mid-17th century, and even more so among the elite groups, who included many rural nobility and gentry with town houses there.[29]

The fortified city temporarily fell to the French invasion in 1672 (theDisaster Year,Dutch: Rampjaar). The French invasion was stopped just west of Utrecht at theOld Hollandic Waterline.In 1674, only two years after the French left, the centre of Utrecht was struck by atornado.The halt to building before construction of flying buttresses in the 15th century now proved to be the undoing of the cathedral of St Martin church's central section which collapsed, creating the current Dom square between the tower and choir. In 1713, Utrecht hosted one of the first international peace negotiations when theTreaty of Utrechtsettled theWar of the Spanish Succession.Beginning in 1723, Utrecht became the centre of the non-RomanOld Catholic Churchesin the world.

Modern history (1815–present)[edit]

In the early 19th century, the role of Utrecht as a fortified town had become obsolete. The fortifications of theNieuwe Hollandse Waterliniewere moved east of Utrecht. The town walls could now be demolished to allow for expansion. The moats remained intact and formed an important feature of the Zocher plantsoen, anEnglish style landscape parkthat remains largely intact today. Growth of the city increased when, in 1843, a railway connecting Utrecht to Amsterdam was opened. After that, Utrecht gradually became the main hub of theDutch railway network.With theindustrial revolutionfinally gathering speed in the Netherlands and the ramparts taken down, Utrecht began to grow far beyond its medieval centre. When the Dutch government allowed the bishopric of Utrecht to be reinstated byRomein 1853, Utrecht became the centre of Dutch Catholicism once more. From the 1880s onward, neighbourhoods such as Oudwijk,Wittevrouwen,Vogelenbuurt to the East, and Lombok to the West were developed. New middle-class residential areas, such as Tuindorp andOog in Al,were built in the 1920s and 1930s. During this period, severalJugendstilhouses and office buildings were built, followed byRietveldwho built theRietveld Schröder House(1924), andDudok's construction of the city theatre (1941).

DuringWorld War II,Utrecht was held by German forces until the general German surrender of the Netherlands on 5 May 1945.BritishandCanadiantroops that had surrounded the city entered it after that surrender, on 7 May 1945. Following the end of World War II, the city grew considerably when new neighbourhoods such asOvervecht,Kanaleneiland,HoogravenandLunettenwere built. Around 2000, theLeidsche Rijnhousing area was developed as an extension of the city to the west.[citation needed]

The area surroundingUtrecht Centraal railway stationand the station itself were developed following modernist ideas of the 1960s, in abrutaliststyle. This development led to the construction of the shopping mallHoog Catharijne,the music centre Vredenburg (Hertzberger,1979), and conversion of part of the ancient canal structure into a highway (Catherijnebaan). Protest against further modernisation of the city centre followed even before the last buildings were finalised. In the early 21st century, the whole area is undergoing change again. The redeveloped music centre TivoliVredenburg opened in 2014 with the original Vredenburg and Tivoli concert and rock and jazz halls brought together in a single building.

Geography[edit]

Climate[edit]

Utrecht experiences a temperateoceanic climate(Köppen:Cfb) similar to all of theNetherlands.

| Climate data forDe Bilt | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 15.1 (59.2) |

18.9 (66.0) |

23.9 (75.0) |

28.9 (84.0) |

33.6 (92.5) |

36.8 (98.2) |

37.5 (99.5) |

35.3 (95.5) |

34.2 (93.6) |

26.7 (80.1) |

18.7 (65.7) |

15.3 (59.5) |

37.5 (99.5) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 6.1 (43.0) |

7.0 (44.6) |

10.5 (50.9) |

14.8 (58.6) |

18.3 (64.9) |

20.9 (69.6) |

23.1 (73.6) |

22.9 (73.2) |

19.5 (67.1) |

14.8 (58.6) |

9.9 (49.8) |

6.7 (44.1) |

14.6 (58.3) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 3.6 (38.5) |

3.9 (39.0) |

6.5 (43.7) |

9.9 (49.8) |

13.4 (56.1) |

16.1 (61.0) |

18.2 (64.8) |

17.8 (64.0) |

14.7 (58.5) |

10.9 (51.6) |

7.0 (44.6) |

4.2 (39.6) |

10.6 (51.1) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 0.9 (33.6) |

0.7 (33.3) |

2.4 (36.3) |

4.5 (40.1) |

8.0 (46.4) |

10.8 (51.4) |

13.0 (55.4) |

12.5 (54.5) |

10.0 (50.0) |

7.1 (44.8) |

3.9 (39.0) |

1.6 (34.9) |

6.3 (43.3) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −24.8 (−12.6) |

−21.6 (−6.9) |

−14.4 (6.1) |

−6.6 (20.1) |

−3.7 (25.3) |

0.2 (32.4) |

3.2 (37.8) |

3.8 (38.8) |

−0.7 (30.7) |

−7.8 (18.0) |

−14.4 (6.1) |

−16.6 (2.1) |

−24.8 (−12.6) |

| Averageprecipitationmm (inches) | 70.3 (2.77) |

62.7 (2.47) |

57.4 (2.26) |

41.1 (1.62) |

58.9 (2.32) |

70.1 (2.76) |

84.8 (3.34) |

83.1 (3.27) |

77.5 (3.05) |

80.7 (3.18) |

79.7 (3.14) |

83.4 (3.28) |

849.7 (33.45) |

| Average precipitation days(≥ 1 mm) | 12 | 10 | 11 | 9 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 12 | 131 |

| Average snowy days | 6 | 6 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 5 | 25 |

| Averagerelative humidity(%) | 87 | 84 | 81 | 75 | 75 | 76 | 77 | 79 | 84 | 86 | 89 | 89 | 82 |

| Mean monthlysunshine hours | 66.6 | 89.6 | 139.4 | 189.2 | 217.5 | 207.1 | 213.9 | 196.3 | 152.8 | 119.3 | 67.4 | 55.5 | 1,714.6 |

| Source 1:Royal Netherlands Meteorological Institute(1991–2020 normals, snowy days normals for 1971–2000)[30] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2:Royal Netherlands Meteorological Institute(1901–present extremes)[31] | |||||||||||||

Population[edit]

Demographics[edit]

|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Source:Lourens & Lucassen 1997,pp. 87–88 (1400–1795) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Utrecht city had a population of 361,924 in 2022. It is a growing municipality and projections are that the population will surpass 392,000 by 2025.[32]As of November 2019, the city of Utrecht has a population of 357,179.[8]

Utrecht has a young population, with many inhabitants in the age category from 20 and 30 years, due to the presence of a large university. About 52% of the population is female, 48% is male. The majority of households (52.5%) in Utrecht are single-person households. About 29% of people living in Utrecht are either married, or have another legal partnership. About 3% of the population of Utrecht is divorced.[32]

Inhabitants by origin[edit]

| 2020[33] | Numbers | % |

|---|---|---|

| Without recent migration background | 228,502 | 63.9% |

| Western migration background | 43,511 | 12.17% |

| Non-Western migration background | 85,584 | 23.93% |

| Morocco | 31,429 | 8.79% |

| Turkey | 14,210 | 3.97% |

| Indonesia | 7,923 | 2.22% |

| Suriname | 7,771 | 2.17% |

| Netherlands AntillesandAruba | 2,907 | 0.81% |

| Total | 357,597 | 100% |

For 62.8% of the population of Utrecht both parents were born in the Netherlands. Approximately 12.4% of the population consists of people with a recent migration background fromWesterncountries, while 24.8% of the population has at least one parent who is of 'non-Western origin' (8.8% from Morocco, 4% Turkey, 3% Surinam and Dutch Caribbean and 9.1% of other countries).[32]

| Population of the city of Utrecht by country of birth of the parents of citizens (2022). Those with a mixed background are counted in the 'non Dutch' groupings.[34] | |

|---|---|

| Country/Territory | Population |

| 227,343 (62,8%) | |

| 30,656 (8.8%) | |

| 13,988 (4.%) | |

| 8,014 (2.3%) | |

| 7,827 (3%) | |

| Other | 59,655 (20,7%) |

Religion[edit]

Utrecht has been the religious centre of the Netherlands since the 8th century. Currently it is the see of the MetropolitanArchbishop of Utrecht,the most senior Dutch Roman Catholic leader.[35][36]Hisecclesiastical provincecovers the whole kingdom.

Utrecht is also the see of the archbishop of theOld Catholic Church,titular head of theUnion of Utrecht,and the location of the offices of theProtestant Church in the Netherlands,the main Dutch Protestant church.

As of 2013, the largest religion is Christianity with 28% of the population being Christian, followed by Islam with 9.9% in 2016 and Hinduism with 0.8%.

Population centres and agglomeration[edit]

The city of Utrecht is subdivided into 10 city quarters, all of which have their own neighbourhood council and service centre for civil affairs.

- Binnenstad

- Oost

- Leidsche Rijn

- West

- Overvecht

- Zuid

- Noordoost

- Zuidwest

- Noordwest

- Vleuten-De Meern

Utrecht is the centre of a densely populated area, a fact which makes concise definitions of its agglomeration difficult, and somewhat arbitrary. The smaller Utrecht agglomeration of continuously built-up areas counts some 420,000 inhabitants and includesNieuwegein,IJsselsteinandMaarssen.It is sometimes argued that the close by municipalitiesDe Bilt,Zeist,Houten,Vianen,Driebergen-Rijsenburg(Utrechtse Heuvelrug), andBunnikshould also be counted towards the Utrecht agglomeration, bringing the total to 640,000 inhabitants. The larger region, including slightly more remote cities such asWoerdenandAmersfoort,counts up to 820,000 inhabitants.[38]

Politics[edit]

| party | seats | |

|---|---|---|

| GroenLinks | 9 | |

| D66 | 8 | |

| VVD | 5 | |

| PvdA | 4 | |

| CDA | 3 | |

| PvDD | 3 | |

| Volt | 3 | |

| Christenunie | 2 | |

| Denk | 1 | |

| Bij1 | 1 | |

| Local parties | 6 | |

Cityscape[edit]

Utrecht's cityscape is dominated by theDom Tower,the tallest belfry in the Netherlands and originally part of theCathedral of Saint Martin.[39]An ongoing debate is over whether any building in or near the centre of town should surpass the Dom Tower in height (112 m [367 ft]). Nevertheless, some tall buildings are now being constructed that will become part of the skyline of Utrecht. The second-tallest building of the city, theRabobank-tower, was completed in 2010 and stands 105 m (344 ft) tall.[40]Two antennas will increase that height to 120 m (394 ft). Two other buildings were constructed around theNieuw Galgenwaardstadium (2007). These buildings, the 'Kantoortoren Galghenwert' and 'Apollo Residence', stand 85.5 m (280.5 ft) and 64.5 m (211.6 ft) high, respectively. The former Utrecht Main Post Office, built in 1924, is still in the city centre at Neude square, but is now serving as library, see alsoUtrecht Post Office.

Another landmark is the old centre and the canal structure in the inner city. TheOudegrachtis a curved canal, partly following the ancient main branch of theRhine.It is lined with the unique wharf-basement structures that create a two-level street along the canals.[41]The inner city has largely retained its medieval structure,[42]and the moat ringing the old town is largely intact.[43]In the 1970s part of the moat was converted into a motorway. It was then converted back into a waterway, the work being finished in 2020.[44][45]

Because of the role of Utrecht as a fortified city, construction outside the medieval centre and its city walls was restricted until the 19th century. Surrounding the medieval core there is a ring of late-19th- and early-20th-century neighbourhoods, with newer neighbourhoods positioned farther out.[46]The eastern part of Utrecht remains fairly open. TheDutch Water Line,moved east of the city in the early 19th century, required open lines of fire, thus prohibiting all permanent constructions until the middle of the 20th century on the east side of the city.[47]

Due to the past importance of Utrecht as a religious centre, several monumental churches were erected, many of which have survived.[48]Most prominent is theDom Church.Other notable churches include the romanesqueSt Peter'sand St John's churches; the gothic churches of St James and St Nicholas; and the Buurkerk, now converted into amuseum for automatically playing musical instruments.

Transport[edit]

Public transport[edit]

Because of its central location, Utrecht is well connected to the rest of the Netherlands and has a well-developed public transport network.

Heavy rail[edit]

Utrecht Centraalis the main railway station of Utrecht and is the largest in the country. There are regular intercity services to all major Dutch cities, including direct services toSchiphol Airport.Utrecht Centraal is a station on thenight service,providing an all-night service to (among others) Schiphol Airport, Amsterdam and Rotterdam, seven days a week. InternationalInterCityExpress(ICE) services to Germany throughArnhemcall at Utrecht Centraal. Regular local trains to all areas surrounding Utrecht also depart from Utrecht Centraal; and service several smaller stations:Utrecht Lunetten;Utrecht Vaartsche Rijn;Utrecht Overvecht;Utrecht Leidsche Rijn;Utrecht Terwijde;Utrecht ZuilenandVleuten.A former stationUtrecht Maliebaanclosed in 1939 and has since been converted into theDutch Railway Museum.

Utrecht is the location of the headquarters ofNederlandse Spoorwegen(English:Dutch Railways), the largest rail operator in the Netherlands, andProRail,the state-owned company responsible for the construction and maintenance of the country's rail infrastructure.

Light rail[edit]

TheUtrecht sneltramis alight railscheme running southwards from Utrecht Centraal to the suburbs ofIJsselstein,Kanaleneiland,Lombok andNieuwegein.The sneltram began operations in 1983 and is currently operated by the private transport companyQbuzz.On 16 December 2019 the new tram line to theUithofstarted operating, creating a directmass transitconnection from thecentral stationto the mainUtrecht universitycampus.[49]

Bus transport[edit]

The main local and regional bus station of Utrecht is located adjacent to Utrecht Centraal railway station, at the East and West entrances. Due to large-scale renovation and construction works at the railway station, the station's bus stops are changing frequently. As a general rule, westbound buses depart from the bus station on the west entrance, other buses from the east side station. Localbusesin Utrecht are operated byQbuzz;its services include a high-frequency service to theUithofuniversity district. The local bus fleet is one of Europe's cleanest, using only buses compliant with theEuro-VI standardas well as electric buses for inner-city transport. Regional buses from the city are operated byArrivaandConnexxion.

The Utrecht Centraal railway station is also served by the pan-European services ofEurolines.Furthermore, it acts as departure and arrival place of many coach companies serving holiday resorts in Spain and France—and during winter inAustriaandSwitzerland.

Cycling[edit]

Like most Dutch cities, Utrecht has an extensive network ofcycle paths,making cycling safe and popular. 33 % of journeys within the city are by bicycle, more than any other mode of transport.[50](Cars, for example, account for 30% of trips). Bicycles are used by young and old people, and by individuals and families. They are mostly traditional, upright, steel-framed bicycles, with few gears. There are also bucket bikes for carrying cargo such as groceries or small children. Thanks in part to the access provided by bicycles, 100% of the population lives in a15-minute cityand more than 90% can get to the major destination types within 10 minutes.[51]In 2014, the city council decided to build the world's largestbicycle parking station,near theCentral Railway Station.[52]This three-floor construction will cost an estimated €48 million and will hold 12,500 bicycles. The bicycle parking station was finally opened on 19 August 2019.[53]

Road transport[edit]

Utrecht is well-connected to the Dutch road network. Two of the most important major roads serve the city of Utrecht: theA12andA2motorways connectAmsterdam,Arnhem,The HagueandMaastricht,as well as Belgium and Germany. Other major motorways in the area are theAlmere–BredaA27and the Utrecht–GroningenA28.[54]Due to the increasing traffic and the ancient city plan, traffic congestion is a common phenomenon in and around Utrecht, causing elevated levels ofair pollutants.This has led to a passionate debate in the city about the best way to improve the city's air quality.

Shipping[edit]

Utrecht has an industrial port located on theAmsterdam-Rijnkanaal.[55]The container terminal has a capacity of 80,000 containers a year. In 2003, the port facilitated the transport of four million tons of cargo; mostly sand, gravel, fertiliser and fodder.[56]Additionally, some tourist boat trips are organised from various places on the Oudegracht; and the city is connected to touristic shipping routes through sluices.[57][58][59]

Economy[edit]

Production industry constitutes a small part of the economy of Utrecht. The economy of Utrecht depends for a large part on the several large institutions located in the city. It is the centre of the Dutch railway network and the location of the head office ofNederlandse Spoorwegen.ProRailis headquartered inDe Inktpot(The Inkwell), the largest brick building in the Netherlands[60](the "UFO" featured on its façade stems from an art program in 2000).Rabobank,a large bank, has its headquarters in Utrecht.[61]

Utrecht is also informally considered[who?]the "capital" of theDutch games industry.[62]It was named byBusiness Finlandin 2023 as one of several capitals for the European games industry as a whole.[63]Utrecht's influence in this field was caused by video game development courses at its universities, which were the first such courses in Europe when launched in 2002. Since 2008 Utrecht has also been home to the studio incubator programDutch Game Garden,which has launched a number of studios in the area.[64][65]By 2014 the program had created 200 jobs.[66]Utrecht is also home toNixxes Software(aPlayStation Studiossubsidiary) as well asSokpop Collective.

Education[edit]

Utrecht hosts several large institutions of higher education. The most prominent of these isUtrecht University(est. 1636), the largest university of theNetherlandswith 30,449 students (as of 2012[update]). The university is partially based in the inner city as well as in theUithofcampus area, on the east side of the city. According toShanghai Jiaotong University's university ranking in 2014, it is the 57th-best university in the world.[67]Utrecht also houses the much smallerUniversity of Humanistic Studies,which houses about 400 students.[68]

Utrecht is home of one of the locations ofTIAS School for Business and Society,focused on post-experience management education and the largest management school of its kind in the Netherlands. In 2008, its executiveMBAprogram was rated the 24th best program in the world by theFinancial Times.[69]

Utrecht is also home to two other large institutions of higher education: the vocational universityHogeschool Utrecht(37,000 students),[70]with locations in the city and the Uithof campus; and theHKU Utrecht School of the Arts(3,000 students).

There are many schools forprimaryand secondary education, allowing parents to select from different philosophies and religions in the school as is inherent in theDutch school system.

Culture[edit]

Utrecht city has an active cultural life, and in the Netherlands is second only to Amsterdam.[9]There are several theatres and theatre companies. The 1941 main city theatre was built byDudok.In addition to theatres, there is a large number of cinemas including three arthouse cinemas. Utrecht is host to the internationalEarly Music Festival(Festival Oude Muziek, for music before 1800) and theNetherlands Film Festival.The city has an important classical music hall Vredenburg (1979 byHerman Hertzberger). Its acoustics are considered among the best of the 20th-century original music halls.[citation needed]The original Vredenburg music hall has been redeveloped as part of the larger station area redevelopment plan and in 2014 gained additional halls that allowed its merger with the rock club Tivoli and the SJU jazzpodium. There are several other venues for music throughout the city. Young musicians are educated in theconservatory,a department of theUtrecht School of the Arts.There is a specialisedmuseumof automatically playing musical instruments.

There are many art galleries in Utrecht. There are also several foundations to support art and artists. Training of artists is done at theUtrecht School of the Arts.TheCentraal Museumhas many exhibitions on the arts, including a permanent exhibition on the works of Utrecht resident illustratorDick Bruna,who is best known for creatingMiffy( "Nijntje", in Dutch). BAK, [Dutch: "Basis voor Actuele Kunst," Basis for Contemporary Art] offers contemporary art exhibitions and public events, as well as a Fellowship program for practitioners involved in contemporary arts, theory and activisms. Although street art is illegal in Utrecht, the Utrechtse Kabouter, a picture of a gnome with a red hat, became a common sight in 2004.[71]Utrecht also houses one of the landmarks of modern architecture, the 1924Rietveld Schröder House,which is listed on UNESCO'sWorld Heritage Sites.

Every Saturday, a paviour adds another letter toThe Letters of Utrecht,an endless poem in the cobblestones of the Oude Gracht in Utrecht. With theLetters,Utrecht has asocial sculptureas a growing monument created for the benefit of future people.

To promote culture, Utrecht city organizes cultural Sundays. During a thematic Sunday, several organisations create a program which is open to everyone without, or with a substantially reduced, admission fee. There are also initiatives foramateurartists. The city subsidises an organisation for amateur education in arts aimed at all inhabitants (Utrechts Centrum voor de Kunsten), as does the university for its staff and students. Additionally there are also several private initiatives. The city council provides coupons for discounts to inhabitants who receive welfare to be used with many of the initiatives.

In 2017, Utrecht was named as a UNESCOCity of Literature.In 2025 the nationalliterature museumwill move from the Hague to Utrecht.

Sports[edit]

Utrecht is home to the premier league (professional)footballclubFC Utrecht,which plays inStadium Nieuw Galgenwaard.It is also the home of Kampong, the largest (amateur) sportsclub in the Netherlands (4,500 members), SV Kampong.[72]Kampong featuresfield hockey,association football,cricket,tennis,squashandboules.Kampong's men and women top hockey squads play in the highest Dutch hockey league, the Rabohoofdklasse. Utrecht is also home to baseball and softball club UVV, which plays in the highest Dutch baseball league: de Hoofdklasse. Utrecht's waterways are used by several rowing clubs. Viking is a large club open to the general public, and the student clubs Orca and Triton compete in theVarsityeach year.

In July 2013, Utrecht hosted theEuropean Youth Olympic Festival,in which more than 2,000 young athletes competed in nine different Olympic sports. In July 2015, Utrecht hosted the Grand Départ and first stage of theTour de France.[73]

Museums[edit]

Utrecht has several smaller and larger museums. Many of those are located in the southern part of the old town, the Museumkwartier.

- Aboriginal Art Museum,[74]located at the Oudegracht and closed since 15 June 2017, this museum had a small exhibit of Australian Aboriginal Art

- BAK, basis voor actuele kunst, an international platform for theoretically-informed, politically driven art and experimental research

- Centraal Museum,located in the MuseumQuarter, this municipal museum has a large collection of art, design, and historical artifacts;

- Dick Bruna huis,[75]art of Centraal Museum on this separate location is dedicated to Miffy creator Dick Bruna.

- Duitse Huishas a collection of historical items including many charters with seals dating from as far back as the early 13th century and a collection of medieval coins.[76]

- Museum Catharijneconvent,Museum of the Catholic Church shows the history of Christian culture and arts in the Netherlands;

- Museum SpeelklokNational Museum in the centre of the city, displays several centuries of mechanical musical instruments;

- Railway Museum (Nederlands Spoorwegmuseum)Railway sponsored museum on the history of the Dutch railways;

- Utrecht Archives,[77]are located at Hamburgerstraat 28 in Utrecht;

- Utrecht university museum[78]Utrecht Universitymuseum includes the ancientbotanical garden;

- Volksbuurtmuseum Wijk C[79]

- Sonnenborgh Observatory[80]observatory and museum that regularly hosts lectures on astronomy, located at Zonnenburg 2 in Utrecht;

- Betje Boerhave Museum[81]museum for the grocer's shop where people can buy old-fashioned food and non-food items, located at Hoogt 6 in Utrecht.

Music and events[edit]

The city has several music venues such asTivoliVredenburg,Tivoli De Helling,ACU,Moira,EKKO, dB's and RASA. Utrecht hosts the yearly Utrecht Early Music Festival (Festival Oude Muziek).[82]Several Editions of theThunderdome,a large gabber music event, have been held inJaarbeurs Utrecht.The city also hostsTrance Energythere. Every summer there used to be theSummer Darknessfestival, which celebratedgoth cultureandmusic.[83]In November theLe Guess Who?festival, focused onindie rock,art rockandexperimental rock,takes place in many of the city's venues.

Theatre[edit]

There are two main theatres in the city, theTheater Kikker[84]and theStadsschouwburg Utrecht.[85]De Parade, a travelling theatre festival, performs in Utrecht in summer. The city also hosts the yearlyFestival aan de Werfwhich offers a selection of contemporary international theatre, together with visual arts, public art and music.

Notable people from Utrecht[edit]

- See also the categoryPeople from Utrecht

Over the ages famous people have been born and/or raised in Utrecht. Among the most famous Utrechters are:

- Pope Adrian VI(1459–1523), head of the Catholic Church

- Louis Andriessen(1939–2021), composer

- Marco van Basten(born 1964), football player

- Dick Bruna(1927–2017), writer and illustrator (Miffy)

- C.H.D. Buys Ballot(1817–1890), meteorologist (Buys-Ballot's law)

- Theo van Doesburg(1883–1931), painter and artist (De Stijlmovement)

- Karel Doorman(1889–1942), Rear Admiral (Battle of the Java Sea)

- Paul Fentener van Vlissingen(1941–2006), businessman and philanthropist

- Anton Geesink(1934–2010),judoka,first non-Japanese worldchampionJudo

- Rijk de Gooyer(1925–2011), actor, writer, comedian and singer

- Sylvia Kristel(1952–2012), actress (Emmanuelle)

- Gerrit Rietveld(1888–1964), designer and architect (De Stijlmovement)

- Dafne Schippers(born 1992), sprinter/heptathlon Olympian

- Herman van Veen(born 1945), actor, musician, singer-songwriter and author ofAlfred J. Kwak

- Wil Velders-Vlasblom(1930–2019), first female alderman in Utrecht

- Jason Wilnis(born 1990), mixed martial artist and former kickbo xingGlory middleweight champion

- Jurriën Timber(born 2001), football player forPremier LeaguesideArsenal,with 15 international caps forThe Dutch National Team

International relations[edit]

This sectionneeds additional citations forverification.(July 2015) |

Twin towns[edit]

Utrecht istwinnedwith:

León,Nicaragua

León,Nicaragua Brno,Czech Republic[86][87]

Brno,Czech Republic[86][87] Pekanbaru,Indonesia

Pekanbaru,Indonesia- previously

Hannover,Germany, between 1970 and 1976

Hannover,Germany, between 1970 and 1976

Other relations[edit]

Portland, Oregon,United States as a friendship city[88]

Portland, Oregon,United States as a friendship city[88]

See also[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^SeeUtrecht sodomy trials § Legacyfor the history of these demonyms.

- ^Almost all other canal cities in The Netherlands (such as Amsterdam and Delft) have the water in canals bordering directly to the road surface

References[edit]

- ^"Burgemeester"[Mayor] (in Dutch). Gemeente Utrecht. Archived fromthe originalon 7 April 2014.Retrieved3 April2014.

- ^abBouman-Eijs, Anita; van Bree, Thijmen; Jonkhoff, Wouter; Koops, Olaf; Manshanden, Walter; Rietveld, Elmer (17 December 2012).De Top 20 van Europese grootstedelijke regio's 1995–2011; Randstad Holland in internationaal perspectief[Top 20 of European metropolitan regions 1995–2011; Randstad Holland compared internationally](PDF)(Technical report) (in Dutch). Delft:TNO.Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 3 March 2014.Retrieved25 July2013.

- ^"Postcodetool for 3512GG".Actueel Hoogtebestand Nederland(in Dutch). Het Waterschapshuis.Archivedfrom the original on 26 December 2018.Retrieved3 April2014.

- ^"Bevolkingsontwikkeling; regio per maand"[Population growth; regions per month].CBS Statline(in Dutch).CBS.1 January 2021.Retrieved2 January2022.

- ^"Bevolkingsontwikkeling; Regionale kerncijfers Nederland"[Regional core figures Netherlands].CBS Statline(in Dutch).CBS.1 January 2020.Retrieved8 March2021.

- ^Jones, Daniel(2011).Roach, Peter;Setter, Jane;Esling, John(eds.).Cambridge English Pronouncing Dictionary(18th ed.). Cambridge University Press.ISBN978-0-521-15255-6.

- ^Wells, John C.(2008).Longman Pronunciation Dictionary(3rd ed.). Longman.ISBN978-1-4058-8118-0.

- ^ab"CBS Statline".Archivedfrom the original on 3 August 2017.Retrieved10 January2020.

- ^abGemeente Utrecht."Utrecht Monitor 2007"(PDF)(in Dutch). Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 6 February 2016.Retrieved6 January2008.

- ^Blasi, Abigail (14 May 2012)."10 of the world's unsung places".Lonely Planet.Archivedfrom the original on 7 August 2017.Retrieved6 August2017.

- ^"Gemeente Utrecht, Geschiedenis Utrecht voor 1528".Archivedfrom the original on 16 October 2008.Retrieved8 September2008.

- ^abcdefghide Bruin, R.E.; Hoekstra, T.J.;Pietersma, A.(1999).Twintig eeuwen Utrecht, korte geschiedenis van de stad(in Dutch). Utrecht: SPOU & Het Utrechts Archief.ISBN90-5479-040-7.

- ^Het Utrechts Archief."Het ontstaan van de stad Utrecht (tot 100)"(in Dutch).Archivedfrom the original on 2 May 2009.Retrieved21 October2009.

- ^van der Sijs, Nicoline (2001).Chronologisch woordenboek. De ouderdom en herkomst van onze woorden en betekenissen(in Dutch). Amsterdam / Antwerp. p. 100.ISBN90-204-2045-3.Archivedfrom the original on 29 December 2008.Retrieved21 October2009.

{{cite book}}:CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^Kloosterman, R.P.J. (2010).Lichte Gaard 9. Archeologisch onderzoek naar het castellum en het bisschoppelijk paleis. Basisrapportage archeologie 41(PDF).StadsOntwikkeling gemeente Utrecht.ISBN978-90-73448-39-1.Archived(PDF)from the original on 6 December 2013.Retrieved15 February2011.

- ^van der Tuuk, Luit (2005). "Denen in Dorestad". In van der Eerden, Ria; et al. (eds.).Jaarboek Oud Utrecht 2005(in Dutch). Utrecht: SPOU. pp. 5–40.ISBN90-71108-24-4.

- ^Janssen, H.P.H. (2002).Geschiedenis van de Middeleeuwen(in Dutch) (12th ed.). Utrecht: Aula. pp. 289–296.ISBN90-274-5377-2.

- ^Stöver, R.J. (1997).De Salvator- of Oudmunsterkerk te Utrecht, Stichtingsmonument van het bisdom Utrecht(in Dutch). Utrecht.

{{cite book}}:CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^"Janskerk Informatie".Archived fromthe originalon 30 December 2007.Retrieved6 January2008.

- ^"Sint Pieterskerk Utrecht".Archivedfrom the original on 3 March 2008.Retrieved5 January2008.

- ^Haverkate, H.M. (1985).Een kerk van papier. De geschiedenis van de voormalige Mariakerk te Utrecht(in Dutch). Zutphen, the Netherlands.

{{cite book}}:CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^Broer, C.J.C. (2000).Uniek in de stad. De oudste geschiedenis van de kloostergemeenschap op de Hohorst sinds 1050 de Sint-Paulusabdij te Utrecht(in Dutch). Utrecht.

{{cite book}}:CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^"Karel V"(in Dutch).Archivedfrom the original on 17 December 2007.Retrieved6 January2008.

- ^"Jacobikerk".Archivedfrom the original on 9 January 2008.Retrieved6 January2008.

- ^"Nicolaikerk".Archivedfrom the original on 24 December 2007.Retrieved6 January2008.

- ^"Geertekerk – Remonstrantse Gemeente Utrecht".Archivedfrom the original on 5 December 2007.Retrieved6 January2008.

- ^"De Utrechtse (Werven"(in Dutch). Gemeente Utrecht. Archived fromthe originalon 16 October 2008.Retrieved27 January2008.

- ^"Historic wharf photos from the Utrecht City Archive".Utrecht City Archive.Retrieved27 January2008.[permanent dead link]

- ^Wayne Franits (2004).Dutch Seventeenth-Century Genre Painting.Yale University Press. p. 65.ISBN0-300-10237-2.

- ^"Klimaattabel De Bilt, langjarige gemiddelden, tijdvak 1981–2010"(PDF)(in Dutch).Royal Netherlands Meteorological Institute.Archived(PDF)from the original on 7 December 2013.Retrieved9 September2013.

- ^"Maandrecords De Bilt"(in Dutch).Royal Netherlands Meteorological Institute.Archivedfrom the original on 5 June 2016.Retrieved9 May2016.

- ^abcGemeente Utrecht."Utrechts onderzoek en cijfers".Archived fromthe originalon 15 October 2009.Retrieved15 October2010.

- ^"CBS Statline".opendata.cbs.nl(in Dutch).Retrieved28 June2023.

- ^"CBS StatLine – Bevolking; leeftijd, herkomstgroepering, geslacht en regio, 1 januari".Archivedfrom the original on 30 June 2017.Retrieved8 August2017.

- ^"Aartsbisdom Utrecht"(in Dutch).Archivedfrom the original on 30 January 2021.Retrieved10 December2007.

- ^"Katholiek Nederland"(in Dutch). Archived fromthe originalon 4 October 2010.Retrieved10 December2007.

- ^"Kerkelijkheid en kerkbezoek, 2010/2013".Centraal Bureau voor de Statistiek. 2 October 2014.Archivedfrom the original on 21 June 2019.Retrieved9 March2017.

- ^CBS Statline (2007)."Gemiddelde bevolking per regio naar leeftijd en geslacht / Gebieden in Nederland 2007".Retrieved5 January2008.[permanent dead link]

- ^"RonDom".Domtoren.nl.Archivedfrom the original on 30 January 2012.Retrieved13 April2011.

- ^"Rabobank Groep".Rabobankgroep.nl. Archived fromthe originalon 24 July 2011.Retrieved13 April2011.

- ^"Cultuurhistorie en Monumenten".Utrecht.nl. 4 December 1993. Archived fromthe originalon 8 June 2011.Retrieved13 April2011.

- ^"Wijksite Binnenstad".Utrecht.nl. 30 March 2011. Archived fromthe originalon 8 June 2011.Retrieved13 April2011.

- ^"Utrecht".Map21ltd. Archived fromthe originalon 7 August 2003.Retrieved13 April2011.

- ^"Joining the circle: Utrecht removes road to be ringed by water once more".DutchNews.nl.11 September 2020.Archivedfrom the original on 22 September 2020.Retrieved23 September2020.

- ^"Utrecht restores historic canal made into motorway in 1970s".The Guardian.14 September 2020.Archivedfrom the original on 19 September 2020.Retrieved23 September2020.

- ^Historische Atlas van de stad Utrecht.ISBN90-8506-189-X

- ^Waterliniepad(in Dutch) (1st ed.). Wandelplatform-LAW. 2004.ISBN90-71068-61-7.

- ^"Kerken Kijken Utrecht | Home".Kerkenkijken.nl.Archivedfrom the original on 24 July 2011.Retrieved13 April2011.

- ^"Railway Gazette: Qbuzz wins Utrecht sneltram concession".Archivedfrom the original on 29 October 2010.Retrieved31 October2010.

- ^"Microsoft Word - Utrecht city document.doc"(PDF).Archived(PDF)from the original on 23 February 2015.Retrieved23 June2014.

- ^Knap, Elizabeth; Ulak, Mehmet Baran; Geurs, Karst T.; Mulders, Alex; Van Der Drift, Sander (December 2023)."A composite X-minute city cycling accessibility metric and its role in assessing spatial and socioeconomic inequalities – A case study in Utrecht, the Netherlands".Journal of Urban Mobility.3:100043.doi:10.1016/j.urbmob.2022.100043.S2CID255256096.

- ^"Utrecht to build world's biggest bike park – for 12,500 bikes – DutchNews.nl".DutchNews.nl.27 April 2014.Archivedfrom the original on 29 March 2015.Retrieved29 March2015.

- ^"Finally fully open: Utrecht's huge bicycle parking garage".Bicycle Dutch.20 August 2019.Archivedfrom the original on 6 February 2023.Retrieved6 February2023.

- ^"Autosnelwegen.nl".Autosnelwegen.nl.Archivedfrom the original on 29 March 2010.Retrieved13 April2011.

- ^Clarke, Michael."Amsterdam-Rhine Canal (canal, the Netherlands) – Britannica Online Encyclopedia".Britannica.Archivedfrom the original on 30 December 2007.Retrieved13 April2011.

- ^"Container Terminal Utrecht".Ctu.net.Archivedfrom the original on 6 January 2011.Retrieved13 April2011.

- ^Martijn Elsinghorst."Rondvaart Utrecht".Vareninutrecht.nl. Archived fromthe originalon 24 July 2011.Retrieved13 April2011.

- ^"50 JAAR REDERIJ".Schuttevaer.Archivedfrom the original on 19 April 2011.Retrieved13 April2011.

- ^"Lovers Rondvaart – In Utrecht uit – de uitagenda over uitgaan restaurants in Utrecht".Inutrechtuit.nl. Archived fromthe originalon 24 June 2011.Retrieved13 April2011.

- ^"De administratiegebouwen van de spoorwegen te Utrecht"(in Dutch). 15 February 2016.Archivedfrom the original on 23 December 2019.Retrieved10 April2020.

- ^"Toezicht - Rabobank".rabobank.nl(in Dutch).Archivedfrom the original on 10 April 2020.Retrieved10 April2020.

- ^"Utrecht is the gaming capital of Europe and that's making millions".IO.1 February 2020.

- ^"Game capitals in Europe"(PDF).

- ^"Game Development".

- ^"Going Dutch: teamLab to launch permanent exhibition in the Netherlands in 2024".The Art Newspaper - International art news and events.26 August 2020.

- ^Bailey, Kat (30 December 2015)."How the Dutch Game Garden Helped Remake Video Games in the Netherlands".VG247.

- ^"World-University-Rankings".shanghairanking.Archived fromthe originalon 3 April 2015.Retrieved30 March2015.

- ^"About the University of Humanistic Studies (Dutch)".Archived fromthe originalon 16 January 2013.Retrieved25 December2012.

- ^Financial Times."FT".Archived fromthe originalon 29 February 2008.Retrieved6 January2008.

- ^Hogeschool Utrecht."Kengetallen HU Jaarverslag".Archived fromthe originalon 18 July 2012.Retrieved7 August2012.

- ^"Home".weebly.Archivedfrom the original on 2 April 2015.Retrieved29 March2015.

- ^"kampong.nl".kampong.nl. Archived fromthe originalon 18 February 2005.Retrieved23 June2014.

- ^"Utrecht 2015: the colour of cycling – News pre-race – Tour de France 2014".Letour.fr. 28 November 2013. Archived fromthe originalon 3 December 2013.Retrieved23 June2014.

- ^"aamu.nl".aamu.nl. 6 June 2014. Archived fromthe originalon 3 July 2014.Retrieved23 June2014.

- ^"Centraal Museum Utrecht"(in Dutch). dick bruna huis. Archived fromthe originalon 17 February 2006.Retrieved23 June2014.

- ^"Over RDO".Ridderlijke Duitsche Orde. Archived fromthe originalon 25 February 2014.Retrieved21 June2014.

- ^"hetutrechtsarchief.nl".hetutrechtsarchief.nl.Archivedfrom the original on 14 May 2017.Retrieved13 July2014.

- ^"web.archive.org – museum.uu.nl".uu.nl.Archived fromthe originalon 12 February 2008.

- ^Etlon (30 September 2007)."Volksbuurtmuseum wijk C".Archived fromthe originalon 30 September 2007.Retrieved23 June2014.

- ^"English - Sonnenborch".Archivedfrom the original on 24 July 2018.Retrieved24 July2018.

- ^"Museum voor het kruideniersbedrijf - Kruideniersmuseum".kruideniersmuseum.nl.Archivedfrom the original on 14 July 2018.Retrieved24 July2018.

- ^"OudeMuziek:: Home".Oudemuziek.nl.Archivedfrom the original on 17 July 2014.Retrieved23 June2014.

- ^Hartley, Brandon (September 2011)."When the Goths Have Their Picnic".Another World Blog.Archivedfrom the original on 25 April 2012.Retrieved10 October2011.

- ^"theaterkikker.nl".theaterkikker.nl.Archivedfrom the original on 27 June 2014.Retrieved23 June2014.

- ^"stadsschouwburg-utrecht.nl".stadsschouwburg-utrecht.nl.Archivedfrom the original on 25 June 2014.Retrieved23 June2014.

- ^"City of Brno Foreign Relations – Statutory city of Brno"(in Czech). City of Brno. 2003. Archived fromthe originalon 15 January 2016.Retrieved6 September2011.

- ^"Brno – Partnerská města"(in Czech). City of Brno. Archived fromthe originalon 23 May 2011.Retrieved17 July2009.

- ^"Portland, Oregon".Washington, DC, US: Sister Cities International. Archived fromthe originalon 27 May 2015.Retrieved4 July2015.

Bibliography[edit]

- Lourens, Piet; Lucassen, Jan (1997).Inwonertallen van Nederlandse steden ca. 1300–1800.Amsterdam: NEHA.ISBN9057420082.