Andes

| Andes Mountains | |

|---|---|

| Spanish:Cordillera de los Andes | |

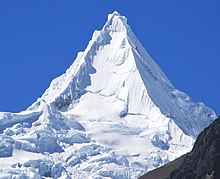

An aerial view of the Andes betweenSantiagoinChileandMendoza, Argentinawith a large ice field on the southern slope ofSan José volcano(left),Marmolejo(right), andTupungato(far right) | |

| Highest point | |

| Peak | Aconcagua,Mendoza,Argentina |

| Elevation | 6,961 m (22,838 ft) |

| Coordinates | 32°39′11.51″S070°0′40.32″W/ 32.6531972°S 70.0112000°W |

| Dimensions | |

| Length | 8,900 km (5,500 mi) |

| Width | 330 km (210 mi) |

| Naming | |

| Native name | Anti(Quechua) |

| Geography | |

| Countries | Argentina,Bolivia,Chile,Colombia,Ecuador,PeruandVenezuela |

| Range coordinates | 32°S70°W/ 32°S 70°W |

TheAndes(/ˈændiːz/AN-deez),Andes MountainsorAndean Mountain Range(Spanish:Cordillera de los Andes;Quechua:Anti) are thelongest continental mountain rangein the world, forming a continuous highland along the western edge ofSouth America.The range is 8,900 km (5,530 mi) long and 200 to 700 km (124 to 435 mi) wide (widest between18°Sand20°Slatitude) and has an average height of about 4,000 m (13,123 ft). The Andes extend from South to North through seven South American countries:Argentina,Chile,Bolivia,Peru,Ecuador,Colombia,andVenezuela.

Along their length, the Andes are split into several ranges, separated by intermediatedepressions.The Andes are the location of several highplateaus—some of which host major cities such asQuito,Bogotá,Cali,Arequipa,Medellín,Bucaramanga,Sucre,Mérida,El Alto,andLa Paz.TheAltiplano Plateauis the world's second highest after theTibetan Plateau.These ranges are in turn grouped into three major divisions based on climate: theTropical Andes,theDry Andes,and theWet Andes.

The Andes are the highest mountain range which is outside ofAsia.The range's highest peak, Argentina'sAconcagua,rises to an elevation of about 6,961 m (22,838 ft) above sea level. ThepeakofChimborazoin the Ecuadorian Andes is farther from the Earth's center than any other location on the Earth's surface, due to theequatorial bulgeresulting from theEarth's rotation.The world's highestvolcanoesare in the Andes, includingOjos del Saladoon the Chile-Argentina border, which rises to 6,893 m (22,615 ft).

The Andes are also part of theAmerican Cordillera,a chain of mountain ranges (cordillera) that consists of an almost continuous sequence of mountain ranges that form the western "backbone" of theAmericasandAntarctica.

Etymology

[edit]The etymology of the wordAndeshas been debated. The majority consensus is that it derives from theQuechuawordanti"east"[1]as inAntisuyu(Quechua for "east region" ),[1]one of the four regions of theInca Empire.

The termcordilleracomes from the Spanish wordcordel"rope"[2]and is used as a descriptive name for several contiguous sections of the Andes, as well as the entire Andean range, and the combined mountain chain along the western part of the North and South American continents.

Geography

[edit]

The Andes can be divided into three sections:

- The Southern Andesin Argentina andChile,south ofLlullaillaco,

- The Central Andesin Peru and Bolivia, and

- The Northern Andesin Venezuela, Colombia, and Ecuador.

At the northern end of the Andes, the separateSierra Nevada de Santa Martarange is often, but not always, treated as part of the Northern Andes.[3]

TheLeeward AntillesislandsAruba,Bonaire,andCuraçao,which lie in theCaribbean Seaoff the coast of Venezuela, were formerly thought to represent the submerged peaks of the extreme northern edge of the Andes range, but ongoing geological studies indicate that such a simplification does not do justice to the complex tectonic boundary between theSouth AmericanandCaribbean plates.[4]

Geology

[edit]| Geology of theAndes |

|---|

| Orogenies |

| Fold-thrust belts |

| Batholiths |

| Subducted structures |

|

| Faults |

| Andean Volcanic Belt |

| Pampean flat-slab |

| Terranes |

The Andes are anorogenicbelt of mountains along thePacific Ring of Fire,a zone ofvolcanic activitythat encompasses the Pacific rim of the Americas as well as theAsia-Pacificregion. The Andes are the result oftectonic plateprocesses extending during theMesozoicandTertiaryeras, caused by thesubductionofoceanic crustbeneath theSouth American Plateas theNazca Plateand South American Plate converge. These processes were accelerated by the effects of climate. As the uplift of the Andes created a rain shadow on the western fringes of Chile, ocean currents and prevailing winds carried moisture away from the Chilean coast. This caused some areas of the subduction zone to be sediment-starved, causing excess friction and an increased rate of compressed coastal uplift.[5]The main cause of the rise of the Andes is the compression of the western rim of theSouth American Platedue to the subduction of theNazca Plateand theAntarctic Plate.To the east, the Andes range is bounded by severalsedimentary basins,such as theOrinoco Basin,theAmazon Basin,theMadre de DiosBasin, and theGran Chaco,that separate the Andes from the ancientcratonsin eastern South America. In the south, the Andes share a long boundary with the formerPatagonia Terrane.To the west, the Andes end at thePacific Ocean,although thePeru-Chile trenchcan be considered their ultimate western limit. From a geographical approach, the Andes are considered to have their western boundaries marked by the appearance of coastal lowlands and less-rugged topography. The Andes also contain large quantities ofiron orelocated in many mountains within the range.

The Andean orogen has a series of bends ororoclines.TheBolivian Oroclineis a seaward-concave bending in the coast of South America and the Andes Mountains at about 18° S.[6][7]At this point, the orientation of the Andes turns from northwest inPeruto south inChileandArgentina.[7]The Andean segments north and south of the Orocline have been rotated 15° counter-clockwise to 20° clockwise respectively.[7][8]The Bolivian Orocline area overlaps with the area of the maximum width of theAltiplano Plateau,and according to Isacks (1988) the Orocline is related tocrustal shortening.[6]The specific point at 18° S where the coastline bends is known as theAricaElbow.[9]Further south lies the Maipo Orocline, a more subtle orocline between 30° S and 38°S with a seaward-concave break in the trend at 33° S.[10]Near the southern tip of the Andes lies the Patagonian Orocline.[11]

Orogeny

[edit]The western rim of theSouth American Platehas been the place of several pre-Andeanorogeniessince at least the lateProterozoicand earlyPaleozoic,when severalterranesandmicrocontinentscollided and amalgamated with the ancientcratonsof eastern South America, by then theSouth American partofGondwana.

The formation of the modern Andes began with the events of theTriassic,whenPangaeabegan the breakup that resulted in developing severalrifts.The development continued through theJurassicPeriod. It was during theCretaceousPeriod that the Andes began to take their present form, by theuplifting,faulting,andfoldingofsedimentaryandmetamorphicrocks of the ancient cratons to the east. The rise of the Andes has not been constant, as different regions have had different degrees of tectonic stress, uplift, anderosion.

Across the 1,000-kilometer-wide (620 mi)Drake Passagelie the mountains of theAntarctic Peninsulasouth of theScotia Plate,which appear to be a continuation of the Andes chain.

The far east regions of the Andes experience a series of changes resulting from the Andean orogeny. Parts of theSunsás OrogeninAmazonian cratondisappeared from the surface of the earth, beingoverriddenby the Andes.[12]TheSierras de Córdoba,where the effects of the ancientPampean orogenycan be observed, owe their modern uplift and relief to theAndean orogenyin theTertiary.[13]Further south in southernPatagonia,the onset of the Andean orogeny caused theMagallanes Basinto evolve from being anextensionalback-arc basinin theMesozoicto being a compressionalforeland basinin theCenozoic.[14]

Seismic activity

[edit]Tectonic forces above thesubduction zonealong the entire west coast of South America where theNazca Plateand a part of theAntarctic Plateare sliding beneath theSouth American Platecontinue to produce an ongoingorogenic eventresulting in minor to majorearthquakesandvolcanic eruptionsto this day. Many high-magnitude earthquakes have been recorded in the region, such as the2010 Maule earthquake(M8.8), the2015 Illapel earthquake(M8.2), and the1960 Valdivia earthquake(M9.5), which as of 2024 was the strongest ever recorded on seismometers.

The amount, magnitude, and type of seismic activity varies greatly along the subduction zone. These differences are due to a wide range of factors, including friction between the plates, angle of subduction, buoyancy of the subducting plate, rate of subduction, and hydration value of the mantle material. The highest rate of seismic activity is observed in the central portion of the boundary, between 33°S and 35°S. In this area, the angle of subduction is very low, meaning the subducting plate is nearly horizontal. Studies of mantle hydration across the subduction zone have shown a correlation between increased material hydration and lower-magnitude, more-frequent seismic activity. Zones exhibiting dehydration instead are thought to have a higher potential for larger, high-magnitude earthquakes in the future.[15]

The mountain range is also a source of shallow intraplate earthquakes within the South American Plate. The largest such earthquake (as of 2024)struck Peru in 1947and measured Ms 7.5. In the Peruvian Andes, these earthquakes display normal (1946), strike-slip (1976), and reverse (1969,1983) mechanisms. The Amazonian Craton is actively underthrusted beneath the sub-Andes region of Peru, producing thrust faults.[16]In Colombia, Ecuador, and Peru, thrust faulting occurs along the sub-Andes due in response to compression brought on by subduction, while in the high Andes, normal faulting occurs in response to gravitational forces.[17]

In the extreme south, a majortransform faultseparatesTierra del Fuegofrom the smallScotia Plate.

Volcanism

[edit]

The Andes range has many active volcanoes distributed in four volcanic zones separated by areas of inactivity. The Andean volcanism is a result of thesubductionof the Nazca Plate and Antarctic Plate underneath the South American Plate. The belt is subdivided into four main volcanic zones that are separated from each other by volcanic gaps. The volcanoes of the belt are diverse in terms of activity style, products, and morphology.[18]While some differences can be explained by which volcanic zone a volcano belongs to, there are significant differences inside volcanic zones and even between neighboring volcanoes. Despite being a typical location forcalc-alkalicand subduction volcanism, the Andean Volcanic Belt has a large range of volcano-tectonic settings, such as rift systems, extensional zones,transpressional faults,subduction ofmid-ocean ridges,andseamountchains apart from a large range of crustal thicknesses andmagmaascent paths, and different amount of crustal assimilations.

Ore deposits and evaporates

[edit]The Andes Mountains host largeoreandsaltdeposits, and some of their easternfold and thrust beltsact as traps for commercially exploitable amounts ofhydrocarbons.In the forelands of theAtacama Desert,some of the largestporphyry coppermineralizations occur, making Chile and Peru the first- and second-largest exporters ofcopperin the world. Porphyry copper in the western slopes of the Andes has been generated byhydrothermal fluids(mostly water) during the cooling ofplutonsor volcanic systems. The porphyry mineralization further benefited from the dry climate that reduced the disturbing actions ofmeteoric water.The dry climate in the central western Andes has also led to the creation of extensivesaltpeter depositswhich were extensively mined until the invention of syntheticnitrates.Yet another result of the dry climate are thesalarsofAtacamaandUyuni,the former being the largest source oflithiumand the latter the world's largest reserve of the element. Early Mesozoic andNeogeneplutonism in Bolivia's Cordillera Central created the Boliviantinbelt as well as the famous, now-mostly-depleted, deposits ofCerro Rico de Potosí.

History

[edit]The Andes Mountains, initially inhabited byhunter-gatherers,experienced the development ofagricultureand the rise of politically centralizedcivilizations,which culminated in the establishment of the century-longInca Empire.This all changed in the 16th century, when the Spanishconquistadorscolonized the mountains in advance of theminingeconomy.

In the tide ofanti-imperialistnationalism, the Andes became the scene of aseries of independence warsin the 19th century, when rebel forces swept through the region to overthrowSpanish colonialrule. Since then, many former Spanish territories have become five independent Andean states.

Climate and hydrology

[edit]

The climate in the Andes varies greatly depending on latitude, altitude, and proximity to the sea. Temperature, atmospheric pressure, and humidity decrease in higher elevations. The southern section is rainy and cool, while the central section is dry. The northern Andes are typically rainy and warm, with an average temperature of 18 °C (64 °F) inColombia.The climate is known to change drastically in rather short distances.Rainforestsexist just kilometers away from the snow-covered peak ofCotopaxi.The mountains have a large effect on the temperatures of nearby areas. Thesnow linedepends on the location. It is between 4,500 and 4,800 m (14,764 and 15,748 ft) in the tropical Ecuadorian, Colombian, Venezuelan, and northern Peruvian Andes, rising to 4,800–5,200 m (15,748–17,060 ft) in the drier mountains of southern Peru and northern Chile south to about30°Sbefore descending to 4,500 m (14,760 ft) on Aconcagua at32°S,2,000 m (6,600 ft) at40°S,500 m (1,640 ft) at50°S,and only 300 m (980 ft) inTierra del Fuegoat55°S;from 50°S, several of the larger glaciers descend to sea level.[19]

The Andes of Chile andArgentinacan be divided into two climatic and glaciological zones: theDry Andesand theWet Andes.Since the Dry Andes extend from the latitudes of theAtacama Desertto the area of theMaule River,precipitation is more sporadic, and there are strong temperature oscillations. The line of equilibrium may shift drastically over short periods of time, leaving a whole glacier in theablationarea or in theaccumulation area.

In the high Andes ofCentral ChileandMendoza Province,rock glaciersare larger and more common than glaciers; this is due to the high exposure tosolar radiation.[20]In these regions, glaciers occur typically at higher altitudes than rock glaciers.[21]The lowest active rock glaciers occur at 900 m a.s.l. inAconcagua.[21]

Though precipitation increases with height, there are semiarid conditions in the nearly-7,000-metre (22,966 ft) highest mountains of the Andes. This drysteppeclimate is considered to be typical of the subtropical position at 32–34° S. The valley bottoms have no woods, just dwarf scrub. The largest glaciers, for example the Plomo Glacier and the Horcones Glaciers, do not even reach 10 km (6.2 mi) in length and have only insignificant ice thickness. At glacial times, however,c.20,000 years ago, the glaciers were over ten times longer. On the east side of this section of the Mendozina Andes, they flowed down to 2,060 m (6,759 ft) and on the west side to about 1,220 m (4,003 ft) above sea level.[22][23]The massifs ofAconcagua(6,961 m (22,838 ft)),Tupungato(6,550 m (21,490 ft)), andNevado Juncal(6,110 m (20,046 ft)) are tens of kilometres away from each other and were connected by a joint ice stream network. The Andes' dendritic glacier arms, components of valley glaciers, were up to 112.5 km (69.9 mi) long and over 1,250 m (4,101 ft) thick, and spanned a vertical distance of 5,150 m (16,896 ft). The climatic glacier snowline (ELA) was lowered from 4,600 m (15,092 ft) to 3,200 m (10,499 ft) at glacial times.[22][24][25][26][27][28][29][30][31]

Flora

[edit]

The Andean region cuts across severalnaturaland floristic regions, due to its extension, fromCaribbeanVenezuela to cold, windy, and wetCape Hornpassing through the hyperaridAtacama Desert.Rainforestsandtropical dry forests[32]used to[when?]encircle much of the northern Andes but are now greatlydiminished,especially in theChocóand inter-Andean valleys of Colombia. Opposite the humid Andean slopes are the relatively dry Andean slopes in most of western Peru, Chile, and Argentina. Along with severalInterandean Valles,they are typically dominated bydeciduouswoodland, shrub andxericvegetation, reaching the extreme in the slopes near the virtually-lifeless Atacama Desert.

About 30,000 species ofvascular plantslive in the Andes, with roughly half beingendemicto the region, surpassing the diversity of any otherhotspot.[33]The small treeCinchona pubescens,a source ofquininewhich is used to treatmalaria,is found widely in the Andes as far south as Bolivia. Other important crops that originated from the Andes aretobaccoandpotatoes.The high-altitudePolylepisforests and woodlands are found in the Andean areas ofColombia,Ecuador,Peru,Bolivia,andChile.These trees, by locals referred to as Queñua, Yagual, and other names, can be found at altitudes of 4,500 m (14,760 ft) above sea level. It remains unclear if the patchy distribution of these forests and woodlands is natural, or the result of clearing which began during theIncanperiod. Regardless, inmodern times,the clearance has accelerated, and the trees are now considered highlyendangered,with some believing that as little as 10% of the original woodland remains.[34]

Fauna

[edit]

The Andes are rich in fauna: With almost 1,000 species, of which roughly 2/3 areendemicto the region, the Andes are the most important region in the world foramphibians.[33]The diversity of animals in the Andes is high, with almost 600 species ofmammals(13% endemic), more than 1,700 species of birds (about 1/3 endemic), more than 600 species ofreptiles(about 45% endemic), and almost 400 species of fish (about 1/3 endemic).[33]

Thevicuñaandguanacocan be found living in theAltiplano,while the closely relateddomesticatedllamaandalpacaare widely kept by locals aspack animalsand for theirmeatandwool.The crepuscular (active during dawn and dusk)chinchillas,two threatened members of therodentorder, inhabit the Andes' alpine regions.[35][36]TheAndean condor,the largest bird of its kind in theWestern Hemisphere,occurs throughout much of the Andes but generally in very low densities.[37]Other animals found in the relatively open habitats of the high Andes include thehuemul,cougar,foxes in the genusPseudalopex,[35][36]and, for birds, certain species oftinamous(notably members of the genusNothoprocta),Andean goose,giant coot,flamingos(mainly associated withhypersalinelakes),lesser rhea,Andean flicker,diademed sandpiper-plover,miners,sierra-finchesanddiuca-finches.[37]

Lake Titicacahosts several endemics, among them the highly endangeredTiticaca flightless grebe[37]andTiticaca water frog.[38]A few species ofhummingbirds,notably somehillstars,can be seen at altitudes above 4,000 m (13,100 ft), but far higherdiversitiescan be found at lower altitudes, especially in the humid Andean forests ( "cloud forests") growing on slopes in Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, Bolivia, and far northwestern Argentina.[37]These forest-types, which includes theYungasand parts of the Chocó, are very rich in flora and fauna, although few large mammals exist, exceptions being the threatenedmountain tapir,spectacled bear,andyellow-tailed woolly monkey.[35]

Birds of humid Andean forests includemountain toucans,quetzals,and theAndean cock-of-the-rock,whilemixed-species flocksdominated bytanagersandfurnariidsare commonly seen—in contrast to several vocal but typically-crypticspecies ofwrens,tapaculos,andantpittas.[37]

A number of species such as theroyal cinclodesandwhite-browed tit-spinetailare associated withPolylepis,and consequently alsothreatened.[37]

Human activity

[edit]This sectionneeds additional citations forverification.(January 2011) |

The Andes Mountains form a north–south axis of cultural influences. A long series of cultural development culminated in the expansion of theInca civilizationandInca Empirein the central Andes during the 15th century. The Incas formed this civilization throughimperialisticmilitarismas well as careful and meticulous governmental management.[39]The government sponsored the construction ofaqueductsandroadsin addition to pre-existing installations. Some of these constructions still exist today.

Devastated by European diseases and bycivil war,the Incas were defeated in 1532 by an alliance composed of tens of thousands of allies from nations they had subjugated (e.g.Huancas,Chachapoyas,Cañaris) and a small army of 180 Spaniards led byFrancisco Pizarro.One of the few Inca sites the Spanish never found in their conquest wasMachu Picchu,which lay hidden on a peak on the eastern edge of the Andes where they descend to the Amazon. The main surviving languages of the Andean peoples are those of theQuechuaandAymara languagefamilies.Woodbine ParishandJoseph Barclay Pentlandsurveyed a large part of the Bolivian Andes from 1826 to 1827.

Cities

[edit]In modern times, the largest cities in the Andes areBogotá,with a metropolitan population of over ten million, andSantiago,Medellín,Cali,andQuito.Limais a coastal city adjacent to the Andes and is the largest city of all Andean countries. It is the seat of theAndean Community of Nations.

La Paz,Bolivia's seat of government, is the highest capital city in the world, at an elevation of approximately 3,650 m (11,975 ft). Parts of the La Paz conurbation, including the city ofEl Alto,extend up to 4,200 m (13,780 ft).

Other cities in or near the Andes includeBariloche,Catamarca,Jujuy,Mendoza,Salta,San Juan,Tucumán,andUshuaiain Argentina;CalamaandRancaguain Chile;Cochabamba,Oruro,Potosí,Sucre,Tarija,andYacuibain Bolivia;Arequipa,Cajamarca,Cusco,Huancayo,Huánuco,Huaraz,Juliaca,andPunoin Peru;Ambato,Cuenca,Ibarra,Latacunga,Loja,Riobamba,andTulcánin Ecuador;Armenia,Cúcuta,Bucaramanga,Duitama,Ibagué,Ipiales,Manizales,Palmira,Pasto,Pereira,Popayán,Sogamoso,Tunja,andVillavicencioin Colombia; andBarquisimeto,La Grita,Mérida,San Cristóbal,Tovar,Trujillo,andValerain Venezuela. The cities ofCaracas,Valencia,andMaracayare in theVenezuelan Coastal Range,which is a debatable extension of the Andes at the northern extremity of South America.

-

View ofMérida, Venezuela

Transportation

[edit]Cities and large towns are connected withasphalt-paved roads, while smaller towns are often connected by dirt roads, which may require afour-wheel-drivevehicle.[40]

The rough terrain has historically put the costs of buildinghighwaysandrailroadsthat cross the Andes out of reach of most neighboring countries, even with moderncivil engineeringpractices. For example, the main crossover of the Andes between Argentina and Chile is still accomplished through thePaso Internacional Los Libertadores.Only recently[when?]have the ends of some highways that came rather close to one another from the east and the west been connected.[41]Much of the transportation of passengers is done via aircraft.

However, there is one railroad that connects Chile with Peru via the Andes, and there are others that make the same connection via southern Bolivia.

There are multiple highways in Bolivia that cross the Andes. Some of these were built during aperiod of warbetween Bolivia andParaguay,in order to transport Bolivian troops and their supplies to the war front in the lowlands of southeastern Bolivia and western Paraguay.

For decades, Chile claimed ownership of land on the eastern side of the Andes. However, these claims were given up in about 1870 during theWar of the Pacificbetween Chile and the allied Bolivia and Peru, in a diplomatic deal to keep Peru out of the war. TheChilean ArmyandChilean Navydefeated the combined forces of Bolivia and Peru, and Chile took over Bolivia's only province on the Pacific Coast, some land from Peru that was returned to Peru decades later. Bolivia has been completelylandlockedever since. It mostly usesseaportsin eastern Argentina andUruguayfor international trade because its diplomatic relations with Chile have been suspended since 1978.

Because of the tortuous terrain in places, villages and towns in the mountains—to which travel viamotorized vehiclesis of little use—are still located in the high Andes of Chile, Bolivia, Peru, andEcuador.Locally, the relatives of thecamel,thellama,and thealpacacontinue to carry out important uses as pack animals, but this use has generally diminished in modern times.Donkeys,mules,and horses are also useful.

Agriculture

[edit]

The ancient peoples of the Andes such as the Incas have practicedirrigationtechniques for over 6,000 years. Because of the mountain slopes,terracinghas been a common practice. Terracing, however, was only extensively employed after Incan imperial expansions to fuel their expanding realm. Thepotatoholds a very important role as an internally-consumed staple crop.Maizewas also an important crop for these people, and was used for the production ofchicha,important to Andean native people. Currently,[when?]tobacco,cotton,andcoffeeare the main export crops.Coca,despite eradication programs in some countries, remains an important crop for legal local use in a mildly stimulatingherbal tea,and illegally for the production ofcocaine.

Irrigation

[edit]

In unirrigated land,pastureis the most common type of land use. In the rainy season (summer), part of the rangeland is used for cropping (mainly potatoes, barley, broad beans, and wheat).

Irrigation is helpful in advancing the sowing data of the summer crops, which guarantees an early yield in periods of food shortage. Also, by early sowing, maize can be cultivated higher up in the mountains (up to 3,800 m (12,500 ft)). In addition, it makes cropping in the dry season (winter) possible and allows the cultivation of frost-resistant vegetable crops likeonionandcarrot.[42]

Mining

[edit]

The Andes rose to fame for their mineral wealth during theSpanish conquest of South America.Although Andean Amerindian peoples crafted ceremonial jewelry of gold and other metals, themineralizationsof the Andes were first mined on a large scale after the Spanish arrival.Potosíin present-dayBoliviaandCerro de Pascoin Peru were among the principal mines of the Spanish Empire in the New World.Río de la PlataandArgentina[43]derive their names from the silver of Potosí.

Currently, mining in the Andes ofChileandPeruplaces these countries as the first and second major producers ofcopperin the world.Perualso contains the 4th-largest goldmine in the world: theYanacocha.The Bolivian Andes principally producetin,although historically silver mining had a huge impact on theeconomyof 17th-century Europe.

There is a long history of mining in the Andes, from the SpanishsilverminesinPotosíin the 16th century to the vast currentporphyry copper depositsofChuquicamataandEscondidain Chile andToquepalain Peru. Other metals, including iron, gold, and tin, in addition to non-metallic resources are important. The Andes have a vast supply of lithium; Argentina, Bolivia, and Chile have the three largest reserves in the world respectively.[44]

Accion Andina's reforestation plan

[edit]Depending on the country, this species goes by different names. In Peru, it is known as queñual, queuña, or queñoa; in Bolivia, as kewiña; in Ecuador, as yagual; and in Argentina, tabaquillo. Regardless of the name,Polylepisis a high-Andean genus encompassing up to 45 species of trees and shrubs distributed across the South American Andes, from Venezuela to Patagonia, found up to 5,000 meters above sea level.[45]

In 2000, biologist Constantino Aucca founded Ecoan, an NGO promoting conservation of threatened species and endangered Andean ecosystems. Since then, the organization has reforested 4.5 million plants across 16 protected areas, involving 37 Andean communities in the process.[45]

Aucca's efforts caught the attention of Florent Kaiser, a Franco-German forest engineer. During a visit to Peru in 2018, Aucca invited Kaiser to the Queuña Raymi festival, where Cusco communities engage in queñual reforestation.[45]

Peaks

[edit]This list contains some of the major peaks in the Andes mountain range. The highest peak is Aconcagua of Argentina.

Argentina

[edit]

- Aconcagua,6,961 m (22,838 ft)

- Cerro Bonete,6,759 m (22,175 ft)

- Galán,5,912 m (19,396 ft)

- Mercedario,6,720 m (22,047 ft)

- Pissis,6,795 m (22,293 ft)

The border between Argentina and Chile

[edit]- Cerro Bayo,5,401 m (17,720 ft)

- Cerro Fitz Roy,3,375 m (11,073 ft) or 3,405 m,Patagonia,also known as Cerro Chaltén

- Cerro Escorial,5,447 m (17,871 ft)

- Cordón del Azufre,5,463 m (17,923 ft)

- Falso Azufre,5,890 m (19,324 ft)

- Incahuasi,6,620 m (21,719 ft)

- Lastarria,5,697 m (18,691 ft)

- Llullaillaco,6,739 m (22,110 ft)

- Maipo,5,264 m (17,270 ft)

- Marmolejo,6,110 m (20,046 ft)

- Ojos del Salado,6,893 m (22,615 ft)

- Olca,5,407 m (17,740 ft)

- Sierra Nevada de Lagunas Bravas,6,127 m (20,102 ft)

- Socompa,6,051 m (19,852 ft)

- Nevado Tres Cruces,6,749 m (22,142 ft) (south summit) (III Region)

- Tronador,3,491 m (11,453 ft)

- Tupungato,6,570 m (21,555 ft)

- Nacimiento,6,492 m (21,299 ft)

Bolivia

[edit]

- Janq'u Uma,6,427 m (21,086 ft)

- Cabaraya,5,860 m (19,226 ft)

- Chacaltaya,5,422 m (17,789 ft)

- Chachacomani,6,074 m (19,928 ft)

- Chaupi Orco,6,044 m (19,829 ft)

- Huayna Potosí,6,088 m (19,974 ft)

- Illampu,6,368 m (20,892 ft)

- Illimani,6,438 m (21,122 ft)

- Laram Q'awa,5,182 m (17,001 ft)

- Macizo de Pacuni,5,400 m (17,720 ft)

- Mururata,5,871 m (19,260 ft)

- Nevado Anallajsi,5,750 m (18,865 ft)

- Nevado Charquini,5,392 m (17,690 ft)

- Nevado Sajama,6,542 m (21,463 ft)

- Patilla Pata,5,300 m (17,390 ft)

- Tata Sabaya,5,430 m (17,815 ft)

- Tunari,5,035 m (16,519 ft)

- Uturuncu,6,008 m (19,711 ft)

- Wayna Potosí,4,969 m (16,302 ft)

Border between Bolivia and Chile

[edit]

- Acotango,6,052 m (19,856 ft)

- Aucanquilcha,6,176 m (20,262 ft)

- Michincha,5,305 m (17,405 ft)

- Iru Phutunqu,5,163 m (16,939 ft)

- Licancabur,5,920 m (19,423 ft)

- Olca,5,407 m (17,740 ft)

- Parinacota,6,348 m (20,827 ft)

- Paruma,5,420 m (17,782 ft)

- Pomerape,6,282 m (20,610 ft)

Chile

[edit]

- Monte San Valentin,4,058 m (13,314 ft)

- Cerro Paine Grande,2,884 m (9,462 ft)

- Cerro Macá,c.2,300 m (7,546 ft)

- Monte Darwin,c.2,500 m (8,202 ft)

- Volcan Hudson,c.1,900 m (6,234 ft)

- Cerro Castillo Dynevor,c.1,100 m (3,609 ft)

- Mount Tarn,c.825 m (2,707 ft)

- Polleras,c.5,993 m (19,662 ft)

- Acamarachi,c.6,046 m (19,836 ft)

Colombia

[edit]

- Nevado del Huila,5,365 m (17,602 ft)

- Nevado del Ruiz,5,321 m (17,457 ft)

- Nevado del Tolima,5,205 m (17,077 ft)

- Pico Pan de Azúcar,5,200 m (17,060 ft)

- Ritacuba Negro,5,320 m (17,454 ft)

- Nevado del Cumbal,4,764 m (15,630 ft)

- Cerro Negro de Mayasquer,4,445 m (14,583 ft)

- Ritacuba Blanco,5,410 m (17,749 ft)

- Nevado del Quindío,5,215 m (17,110 ft)

- Puracé,4,655 m (15,272 ft)

- Santa Isabel,4,955 m (16,257 ft)

- Doña Juana,4,150 m (13,615 ft)

- Galeras,4,276 m (14,029 ft)

- Azufral,4,070 m (13,353 ft)

Ecuador

[edit]

- Antisana,5,752 m (18,871 ft)

- Cayambe,5,790 m (18,996 ft)

- Chiles,4,723 m (15,495 ft)

- Chimborazo,6,268 m (20,564 ft)

- Corazón,4,790 m (15,715 ft)

- Cotopaxi,5,897 m (19,347 ft)

- El Altar,5,320 m (17,454 ft)

- Illiniza,5,248 m (17,218 ft)

- Pichincha,4,784 m (15,696 ft)

- Quilotoa,3,914 m (12,841 ft)

- Reventador,3,562 m (11,686 ft)

- Sangay,5,230 m (17,159 ft)

- Tungurahua,5,023 m (16,480 ft)

Peru

[edit]

- Alpamayo,5,947 m (19,511 ft)

- Artesonraju,6,025 m (19,767 ft)

- Carnicero,5,960 m (19,554 ft)

- Chumpe,6,106 m (20,033 ft)

- Coropuna,6,377 m (20,922 ft)

- El Misti,5,822 m (19,101 ft)

- El Toro,5,830 m (19,127 ft)

- Huandoy,6,395 m (20,981 ft)

- Huascarán,6,768 m (22,205 ft)

- Jirishanca,6,094 m (19,993 ft)

- Pumasillo,5,991 m (19,656 ft)

- Rasac,6,040 m (19,816 ft)

- Rondoy,5,870 m (19,259 ft)

- Sarapo,6,127 m (20,102 ft)

- Salcantay,6,271 m (20,574 ft)

- Seria Norte,5,860 m (19,226 ft)

- Siula Grande,6,344 m (20,814 ft)

- Huaytapallana,5,557 m (18,232 ft)

- Yerupaja,6,635 m (21,768 ft)

- Yerupaja Chico,6,089 m (19,977 ft)

Venezuela

[edit]

- Pico Bolívar,4,978 m (16,332 ft)

- Pico Humboldt,4,940 m (16,207 ft)

- Pico Bonpland,4,880 m (16,010 ft)

- Pico La Concha,4,920 m (16,142 ft)

- Pico Piedras Blancas,4,740 m (15,551 ft)

- Pico El Águila,4,180 m (13,714 ft)

- Pico El Toro4,729 m (15,515 ft)

- Pico El León4,740 m (15,551 ft)

- Pico Mucuñuque4,609 m (15,121 ft)

See also

[edit]- Andean Geology—ascientific journal

- Andesite line

- Apu (god)

- Mountain passes of the Andes

- List of mountain ranges

- Sutter Buttes

Notes

[edit]- ^abTeofilo Laime Ajacopa, Diccionario Bilingüe Iskay simipi yuyayk'ancha, La Paz, 2007 (Quechua–Spanish dictionary)

- ^"Cordillera".etimologias.dechile.net.Retrieved27 December2015.

- ^"Mountains, biodiversity and conservation".Food and Agriculture Organization.Retrieved28 January2019.

- ^Miller, Meghan S.; Levander, Alan; Niu, Fenglin; Li, Aibing (23 June 2008)."Upper mantle structure beneath the Caribbean-South American plate boundary from surface wave tomography"(PDF).Journal of Geophysical Research.114(B1): B01312.Bibcode:2009JGRB..114.1312M.doi:10.1029/2007JB005507.Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 5 June 2010.Retrieved21 November2010.

- ^Lamb, Simon; Davis, Paul (2003)."Cenozoic climate change as a possible cause for the rise of the Andes".Nature.425(6960): 792–797.Bibcode:2003Natur.425..792L.doi:10.1038/nature02049.PMID14574402.S2CID4354886.

- ^abIsacks, Bryan L. (1988),"Uplift of the Central Andean Plateau and Bending of the Bolivian Orocline"(PDF),Journal of Geophysical Research,93(B4): 3211–3231,Bibcode:1988JGR....93.3211I,doi:10.1029/jb093ib04p03211

- ^abcKley, J. (1999), "Geologic and geometric constraints on a kinematic model of the Bolivian orocline",Journal of South American Earth Sciences,12(2): 221–235,Bibcode:1999JSAES..12..221K,doi:10.1016/s0895-9811(99)00015-2

- ^Beck, Myrl E. (1987), "Tectonic rotations on the leading edge of South America: The Bolivian orocline revisited",Geology,15(9): 806–808,Bibcode:1987Geo....15..806B,doi:10.1130/0091-7613(1987)15<806:trotle>2.0.co;2

- ^Prezzi, Claudia B.; Vilas, Juan F. (1998). "New evidence of clockwise vertical axis rotations south of the Arica elbow (Argentine Puna)".Tectonophysics.292(1): 85–100.Bibcode:1998Tectp.292...85P.doi:10.1016/s0040-1951(98)00058-4.

- ^Arriagada, César; Ferrando, Rodolfo; Córdova, Loreto; Morata, Diego; Roperch, Pierrick (2013),"The Maipo Orocline: A first scale structural feature in the Miocene to Recent geodynamic evolution in the central Chilean Andes"(PDF),Andean Geology,40(3): 419–437

- ^Charrier, Reynaldo;Pinto, Luisa; Rodríguez, María Pía (2006). "3. Tectonostratigraphic evolution of the Andean Orogen in Chile". In Moreno, Teresa; Gibbons, Wes (eds.).Geology of Chile.Geological Society of London. pp. 5–19.ISBN978-1-86239-219-9.

- ^Santos, J.O.S.; Rizzotto, G.J.; Potter, P.E.; McNaughton, N.J.; Matos, R.S.; Hartmann, L.A.; Chemale Jr., F.; Quadros, M.E.S. (2008). "Age and autochthonous evolution of the Sunsás Orogen in West Amazon Craton based on mapping and U–Pb geochronology".Precambrian Research.165(3–4): 120–152.Bibcode:2008PreR..165..120S.doi:10.1016/j.precamres.2008.06.009.

- ^Rapela, C.W.;Pankhurst, R.J;Casquet, C.; Baldo, E.; Saavedra, J.; Galindo, C.; Fanning, C.M. (1998)."The Pampean Orogeny of the southern proto-Andes: Cambrian continental collision in the Sierras de Córdoba"(PDF).In Pankhurst, R.J; Rapela, C.W. (eds.).The Proto-Andean Margin of Gondwana.Vol. 142. pp. 181–217.doi:10.1144/GSL.SP.1998.142.01.10.S2CID128814617.Archived(PDF)from the original on 9 October 2022.Retrieved7 December2015.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - ^Wilson, T.J. (1991). "Transition from back-arc to foreland basin development in the southernmost Andes: Stratigraphic record from the Ultima Esperanza District, Chile".Geological Society of America Bulletin.103(1): 98–111.Bibcode:1991GSAB..103...98W.doi:10.1130/0016-7606(1991)103<0098:tfbatf>2.3.co;2.

- ^Rodriguez Piceda, Constanza; Gao, Ya-Jian; Cacace, Mauro; Scheck-Wenderoth, Magdalena; Bott, Judith; Strecker, Manfred; Tilmann, Frederik (17 March 2023)."The influence of mantle hydration and flexure on slab seismicity in the southern Central Andes".Communications Earth & Environment.4(1): 79.Bibcode:2023ComEE...4...79R.doi:10.1038/s43247-023-00729-1.ISSN2662-4435.

- ^Dorbath, L.; Dorbath, C.; Jimenez, E.; Rivera, L. (1991)."Seismicity and tectonic deformation in the Eastern Cordillera and the sub-Andean zone of central Peru"(PDF).Journal of South American Earth Sciences.4(1–2): 13-24.Bibcode:1991JSAES...4...13D.doi:10.1016/0895-9811(91)90015-D.

- ^Suárez, Gerardo; Molnar, Peter; Burchfiel, B. Clark (1983). "Seismicity, fault plane solutions, depth of faulting, and active tectonics of the Andes of Peru, Ecuador, and southern Colombia".Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth.88(B12): 10403–10428.Bibcode:1983JGR....8810403S.doi:10.1029/JB088iB12p10403.

- ^González-Maurel, Osvaldo; le Roux, Petrus; Godoy, Benigno; Troll, Valentin R.; Deegan, Frances M.; Menzies, Andrew (15 November 2019)."The great escape: Petrogenesis of low-silica volcanism of Pliocene to Quaternary age associated with the Altiplano-Puna Volcanic Complex of northern Chile (21°10′-22°50′S)".Lithos.346–347: 105162.Bibcode:2019Litho.34605162G.doi:10.1016/j.lithos.2019.105162.ISSN0024-4937.S2CID201291787.

- ^ "Climate of the Andes".Archived fromthe originalon 14 December 2007.Retrieved9 December2007.

- ^Jan-Christoph Otto, Joachim Götz, Markus Keuschnig, Ingo Hartmeyer, Dario Trombotto, and Lothar Schrott (2010). Geomorphological and geophysical investigation of a complex rock glacier system—Morenas Coloradas valley (Cordon del Plata, Mendoza, Argentina)

- ^abCorte, Arturo E. (1976). "Rock glaciers".Biuletyn Peryglacjalny.26:175–197.

- ^abKuhle, M. (2011): The High-Glacial (Last Glacial Maximum) Glacier Cover of the Aconcagua Group and Adjacent Massifs in the Mendoza Andes (South America) with a Closer Look at Further Empirical Evidence. Development in Quaternary Science, Vol. 15 (Quaternary Glaciation – Extent and Chronology, A Closer Look, Eds: Ehlers, J.; Gibbard, P.L.; Hughes, P.D.), 735–738. (Elsevier B.V., Amsterdam).

- ^Brüggen, J. (1929): Zur Glazialgeologie der chilenischen Anden. Geol. Rundsch. 20, 1–35, Berlin.

- ^Kuhle, M. (1984): Spuren hocheiszeitlicher Gletscherbedeckung in der Aconcagua-Gruppe (32–33° S). In: Zentralblatt für Geologie und Paläontologie Teil 1 11/12, Verhandlungsblatt des Südamerika-Symposiums 1984 in Bamberg: 1635–1646.

- ^Kuhle, M. (1986): Die Vergletscherung Tibets und die Entstehung von Eiszeiten. In: Spektrum der Wissenschaft 9/86: 42–54.

- ^Kuhle, M. (1987): Subtropical Mountain- and Highland-Glaciation as Ice Age Triggers and the Waning of the Glacial Periods in the Pleistocene. In: GeoJournal 14 (4); Kluwer, Dordrecht/ Boston/ London: 393–421.

- ^Kuhle, M. (1988): Subtropical Mountain- and Highland-Glaciation as Ice Age Triggers and the Waning of the Glacial Periods in the Pleistocene. In: Chinese Translation Bulletin of Glaciology and Geocryology 5 (4): 1–17 (in Chinese language).

- ^Kuhle, M. (1989): Ice-Marginal Ramps: An Indicator of Semiarid Piedmont Glaciations. In: GeoJournal 18; Kluwer, Dordrecht/ Boston/ London: 223–238.

- ^Kuhle, M. (1990): Ice Marginal Ramps and Alluvial Fans in Semi-Arid Mountains: Convergence and Difference. In: Rachocki, A.H., Church, M. (eds.): Alluvial fans: A field approach. John Wiley & Sons Ltd, Chester-New York-Brisbane-Toronto-Singapore: 55–68.

- ^Kuhle, M. (1990): The Probability of Proof in Geomorphology—an Example of the Application of Information Theory to a New Kind of Glacigenic Morphological Type, the Ice-marginal Ramp (Bortensander). In: GeoJournal 21 (3); Kluwer, Dordrecht/ Boston/ London: 195–222.

- ^Kuhle, M. (2004): The Last Glacial Maximum (LGM) glacier cover of the Aconcagua group and adjacent massifs in the Mendoza Andes (South America). In: Ehlers, J., Gibbard, P.L. (Eds.), Quaternary Glaciation— Extent and Chronology. Part III: South America, Asia, Africa, Australia, Antarctica. Development in Quaternary Science, vol. 2c. Elsevier B.V., Amsterdam, pp. 75–81.

- ^"Tropical and Subtropical Dry Broadleaf Forest Ecoregions".wwf.panda.org.Archived fromthe originalon 25 April 2012.Retrieved27 December2015.

- ^abcTropical AndesArchived21 August 2010 at theWayback Machine– biodiversityhotspots.org

- ^"Pants of the Andies".Archived fromthe originalon 15 December 2007.Retrieved9 December2007.

- ^abcEisenberg, J.F.; & Redford, K.H. (2000).Mammals of the Neotropics, Volume 3: The Central Neotropics: Ecuador, Peru, Bolivia, Brazil.ISBN978-0-226-19542-1

- ^abEisenberg, J.F.; & Redford, K.H. (1992).Mammals of the Neotropics, Volume 2: The Southern Cone: Chile, Argentina, Uruguay, Paraguay.ISBN978-0-226-70682-5

- ^abcdefFjeldsaa, J.; & Krabbe, N. (1990).Birds of the High Andes: A Manual to the Birds of the Temperate Zone of the Andes and Patagonia, South America.ISBN978-87-88757-16-3

- ^Stuart, Hoffmann, Chanson, Cox, Berridge, Ramani and Young, editors (2008).Threatened Amphibians of the World.ISBN978-84-96553-41-5

- ^D'Altroy, Terence N. The Incas. Blackwell Publishing, 2003

- ^"Andes travel map".Archived fromthe originalon 24 September 2010.Retrieved20 June2010.

- ^"Jujuy apuesta a captar las cargas de Brasil en tránsito hacia Chileby Emiliano Galli ".La Nación.La Nación newspaper. 7 August 2009.Retrieved22 July2011.

- ^W. van Immerzeel, 1989.Irrigation and erosion/flood control at high altitudes in the Andes.Published in Annual Report 1989, pp. 8–24, International Institute for Land Reclamation and Improvement, Wageningen, The Netherlands. On line:[1]

- ^"Information on Argentina".Argentine Embassy London.

- ^"Lithium: What Role Does Tesla Play In The Demand For This Precious Metal? - Commodity".commodity.Retrieved9 March2023.

- ^abcRuiz, Iván Antezana Q., Flor (11 January 2024)."Más de 10 millones de árboles nuevos: el premiado plan que reforesta los Andes".El País América(in Spanish).Retrieved12 February2024.

{{cite web}}:CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

References

[edit]- Oncken, Onno; et al. (2006).The Andes.Frontiers in Earth Sciences.doi:10.1007/978-3-540-48684-8.ISBN978-3-540-24329-8.

- Biggar, J. (2005).The Andes: A Guide For Climbers.3rd. edition. Andes: Kirkcudbrightshire.ISBN0-9536087-2-7

- de Roy, T. (2005).The Andes: As the Condor Flies.Firefly books: Richmond Hill.ISBN1-55407-070-8

- Fjeldså, J. & N. Krabbe (1990).The Birds of the High Andes.Zoological Museum, University of Copenhagen:ISBN87-88757-16-1

- Fjeldså, J. & M. Kessler (1996).Conserving the biological diversity of Polylepis woodlands of the highlands on Peru and Bolivia, a contribution to sustainable natural resource management in the Andes.NORDECO: Copenhagen.ISBN978-87-986168-0-1

Bibliography

[edit]- Biggar, John (2005).The Andes: A Guide for Climbers(3 ed.). Scotland: Andes Publishing.ISBN978-0-9536087-2-0.

- Darack, Ed (2001).Wild Winds: Adventures in the Highest Andes.Cordee / DPP.ISBN978-1-884980-81-7.

External links

[edit]- .Encyclopædia Britannica.Vol. II (9th ed.). 1878. p. 15-18.

- University of Arizona: Andes geology

- Blueplanetbiomes.org: Climate and animal life of the AndesArchived14 December 2007 at theWayback Machine

- Discover-peru.org: Regions and Microclimates in the Andes

- Peaklist.org: Complete list of mountains in South America with an elevation at/above 1,500 m (4,920 ft)