Arabic script

This articlemay need to be rewrittento comply with Wikipedia'squality standards.(July 2022) |

| Arabic script | |

|---|---|

| |

| Script type | primarily,Alpha bet |

Time period | 4th century CE to the present[1] |

| Direction | Right-to-left script |

| Official script | 20 sovereign states Co-official script in: Official script at regional level in: |

| Languages | See below |

| Related scripts | |

Parent systems | |

Child systems | N'Ko Thaana Hanifi script Persian Alpha bet |

| ISO 15924 | |

| ISO 15924 | Arab(160),Arabic |

| Unicode | |

Unicode alias | Arabic |

| |

TheArabic scriptis thewriting systemused forArabicand several other languages of Asia and Africa. It is the second-most widely usedAlpha beticwriting system in the world (after theLatin script),[2]the second-most widely usedwriting systemin the world by number of countries using it, and the third-most by number of users (after the Latin andChinese scripts).[3]

The script was first used to write texts in Arabic, most notably theQuran,the holy book ofIslam.Withthe religion's spread,it came to be used as the primary script for many language families, leading to the addition of new letters and other symbols. Such languages still using it are:Persian(FarsiandDari),Malay(Jawi),Cham(Akhar Srak),[4]Uyghur,Kurdish,Punjabi(Shahmukhi),Sindhi,Balti,Balochi,Pashto,Luri,Urdu,Kashmiri,Rohingya,Somali,Mandinka,andMooré,among others.[5]Until the 16th century, it was also used for someSpanishtexts, and—prior to thescript reform in 1928—it was the writing system ofTurkish.[6]

The script is written fromright to leftin acursivestyle, in which most of the letters are written in slightly different forms according to whether they stand alone or are joined to a following or preceding letter. The script does not havecapital letters.[7]In most cases, the letters transcribeconsonants,or consonants and a few vowels, so most Arabic Alpha bets areabjads,with the versions used for some languages, such asKurdish dialect of Sorani,Uyghur,Mandarin,andBosniak,beingAlpha bets.It is the basis for the tradition ofArabic calligraphy.

| Part ofa serieson |

| Calligraphy |

|---|

|

History

[edit]The Arabic Alpha bet is derived either from theNabataean Alpha bet[8][9]or (less widely believed) directly from theSyriac Alpha bet,[10]which are both derived from theAramaic Alpha bet(which also gave rise to theHebrew Alpha bet), which, in turn, descended from thePhoenician Alpha bet.In addition to the Aramaic script (and, therefore, the Arabic and Hebrew scripts), the Phoenician script also gave rise to theGreek Alpha bet(and, therefore, both theCyrillic Alpha betand theLatin Alpha betused in America and most European countries.).

Origins

[edit]In the 6th and 5th centuries BCE, northern Arab tribes emigrated and founded a kingdom centred aroundPetra,Jordan.These people (now namedNabataeansfrom the name of one of the tribes, Nabatu) spokeNabataean Arabic,a dialect of theArabiclanguage. In the 2nd or 1st centuries BCE,[11][12]the first known records of the Nabataean Alpha bet were written in theAramaic language(which was the language of communication and trade), but included some Arabic language features: the Nabataeans did not write the language which they spoke. They wrote in a form of the Aramaic Alpha bet, which continued to evolve; it separated into two forms: one intended forinscriptions(known as "monumental Nabataean" ) and the other, more cursive and hurriedly written and with joined letters, for writing onpapyrus.[13]This cursive form influenced the monumental form more and more and gradually changed into the Arabic Alpha bet.

Overview

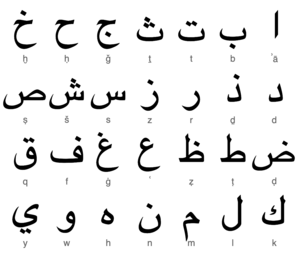

[edit]| خ | ح | ج | ث | ت | ب | ا |

| khā’ | ḥā’ | jīm | tha’ | tā’ | bā’ | alif |

| ص | ش | س | ز | ر | ذ | د |

| ṣād | shīn | sīn | zāy/ zayn |

rā’ | dhāl | dāl |

| ق | ف | غ | ع | ظ | ط | ض |

| qāf | fā’ | ghayn | ‘ayn | ẓā’ | ṭā’ | ḍād |

| ي | و | ه | ن | م | ل | ك |

| yā’ | wāw | hā’ | nūn | mīm | lām | kāf |

| أ | آ | إ | ئ | ؠ | ء | ࢬ |

| alif hamza↑ | alif madda | alif hamza↓ | yā’ hamza↑ | kashmiri yā’ | hamza | rohingya yā’ |

| ى | ٱ | ی | ە | ً | ٌ | ٍ |

| alif maksura | alif wasla | farsi yā’ | ae | fathatan | dammatan | kasratan |

| َ | ُ | ِ | ّ | ْ | ٓ | ۤ |

| fatha | damma | kasra | shadda | sukun | maddah | madda |

| ں | ٹ | ٺ | ٻ | پ | ٿ | ڃ |

| nūn ghunna | ttā’ | ttāhā’ | bāā’ | pā’ | tāhā’ | nyā’ |

| ڄ | چ | ڇ | ڈ | ڌ | ڍ | ڎ |

| dyā’ | tchā’ | tchahā’ | ddāl | dāhāl | ddāhāl | duul |

| ڑ | ژ | ڤ | ڦ | ک | ڭ | گ |

| rrā’ | jā’ | vā’ | pāḥā’ | kāḥā’ | ng | gāf |

| ڳ | ڻ | ھ | ہ | ة | ۃ | ۅ |

| gueh | rnūn | hā’ doachashmee | hā’ goal | tā’ marbuta | tā’ marbuta goal | kirghiz oe |

| ۆ | ۇ | ۈ | ۉ | ۋ | ې | ے |

| oe | u | yu | kirghiz yu | ve | e | yā’ barree |

| (see below for other Alpha bets) | ||||||

The Arabic script has been adapted for use in a wide variety of languages aside from Arabic, includingPersian,MalayandUrdu,which are notSemitic.Such adaptations may feature altered or new characters to representphonemesthat do not appear in Arabicphonology.For example, the Arabic language lacks avoiceless bilabial plosive(the[p]sound), therefore many languages add their own letter to represent[p]in the script, though the specific letter used varies from language to language. These modifications tend to fall into groups:IndianandTurkic languageswritten in the Arabic script tend to use thePersian modified letters,whereas thelanguages of Indonesiatend to imitate those ofJawi.The modified version of the Arabic script originally devised for use with Persian is known as thePerso-Arabic scriptby scholars.[citation needed]

When the Arabic script is used to writeSerbo-Croatian,Sorani,Kashmiri,Mandarin Chinese,orUyghur,vowels are mandatory. The Arabic script can, therefore, be used as a trueAlpha betas well as anabjad,although it is often strongly, if erroneously, connected to the latter due to it being originally used only for Arabic.[citation needed]

Use of the Arabic script inWest Africanlanguages, especially in theSahel,developed with the spread ofIslam.To a certain degree the style and usage tends to follow those of theMaghreb(for instance the position of the dots in the lettersfāʼandqāf).[14][15]Additionaldiacriticshave come into use to facilitate the writing of sounds not represented in the Arabic language. The termʻAjamī,which comes from the Arabic root for "foreign", has been applied to Arabic-based orthographies of African languages.[citation needed]

Table of writing styles

[edit]| Script or style | Alphabet(s) | Language(s) | Region | Derived from | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Naskh | Arabic, Pashto, & others |

Arabic, Pashto, Sindhi, & others |

Every region where Arabic scripts are used | Sometimes refers to a veryspecific calligraphic style,but sometimes used to refer more broadly to almost every font that is notKuficorNastaliq. | |

| Nastaliq | Urdu, Shahmukhi, Persian, & others |

Urdu, Punjabi, Persian, Kashmiri & others |

Southern and Western Asia | Taliq | Used for almost all modern Urdu and Punjabi text, but only occasionally used for Persian. (The term "Nastaliq" is sometimes used by Urdu-speakers to refer to all Perso-Arabic scripts.) |

| Taliq | Persian | Persian | A predecessor ofNastaliq. | ||

| Kufic | Arabic | Arabic | Middle East and parts of North Africa | ||

| Rasm | RestrictedArabic Alpha bet | Arabic | Mainly historical | Omits all diacritics includingi'jam.Digital replication usually requires some special characters. See:ٮڡٯ (links to Wiktionary). |

Table of Alpha bets

[edit]| Alphabet | Letters | Additional Characters |

Script or Style | Languages | Region | Derived from: (or related to) |

Note |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arabic | 28 | ^(see above) | Naskh,Kufi,Rasm,& others | Arabic | North Africa, West Asia | Aramaic, Syriac, Nabataean |

|

| Ajami script | 33 | ٻتٜتٰٜ | Naskh | Hausa,Yoruba,Swahili | West Africa | Arabic | Abjad | documented use likely between the 15th to 18th century for Hausa, Mande, Pulaar, Swahili, Wolof, and Yoruba Languages |

| Aljamiado | 28 | Maghrebi, Andalusi variant;Kufic | Old Spanish,Andalusi Romance,Ladino,Aragonese,Valencian,Old Galician-Portuguese | Southwest Europe | Arabic | 8th–13th centuries for Andalusi Romance, 14th–16th centuries for the other languages | |

| Arebica | 30 | ڄەاٖىيڵںٛۉۆ | Naskh | Serbo-Croatian | Southeastern Europe | Perso-Arabic | Latest stage has full vowel marking |

| Arwi Alpha bet | 41 | ڊڍڔصٜۻࢳڣࢴڹݧ | Naskh | Tamil | Southern India, Sri Lanka | Perso-Arabic | |

| Belarusian Arabic Alpha bet | 32 | ࢮࢯ | Naskh | Belarusian | Eastern Europe | Perso-Arabic | 15th / 16th century |

| Balochi Standard Alphabet(s) | 29 | ٹڈۏݔے | NaskhandNastaliq | Balochi | South-West Asia | Perso-Arabic,also borrows multiple glyphs fromUrdu | This standardization is based on the previous orthography. For more information, seeBalochi writing. |

| Berber Arabic Alpha bet(s) | 33 | چژڞݣء | VariousBerber languages | North Africa | Arabic | ||

| Burushaski | 53 | ݳݴݼڅڎݽڞݣݸݹݶݷݺݻ (see note) |

Nastaliq | Burushaski | South-West Asia (Pakistan) | Urdu | Also uses the additional letters shown for Urdu.(see below)Sometimes written with just the Urdu Alpha bet, or with theLatin Alpha bet. |

| Chagatai Alpha bet | 32 | ݣ | NastaliqandNaskh | Chagatai | Central Asia | Perso-Arabic | ݣ is interchangeable with نگ and ڭ. |

| Dobrujan Tatar | 32 | Naskh | Dobrujan Tatar | Southeastern Europe | Chagatai | ||

| Galal | 32 | Naskh | Somali | Horn of Africa | Arabic | ||

| Jawi | 36 | ڠڤݢڽۏى | Naskh | Malay | Peninsular Malaysia, Sumatra and part of Borneo | Perso-Arabic | Since 1303 AD (Trengganu Stone) |

| Kashmiri | 44 | ۆۄؠێ | Nastaliq | Kashmiri | South Asia | Urdu | This orthography is fully voweled. 3 out of the 4 (ۆ, ۄ, ێ) additional glyphs are actually vowels. Not all vowels are listed here since they are not separate letters. For further information, seeKashmiri writing. |

| Kazakh Arabic Alpha bet | 35 | ٵٶۇٷۋۆەھىٸي | Naskh | Kazakh | Central Asia, China | Chagatai | In use since 11th century, reformed in the early 20th century, now official only in China |

| Khowar | 45 | ݯݮڅځݱݰڵ | Nastaliq | Khowar | South Asia | Urdu,however, borrows multiple glyphs fromPashto | |

| Kyrgyz Arabic Alpha bet | 33 | ۅۇۉۋەىي | Naskh | Kyrgyz | Central Asia | Chagatai | In use since 11th century, reformed in the early 20th century, now official only in China |

| Pashto | 45 | ټڅځډړږښګڼۀيېۍئ | Naskhand occasionally,Nastaliq | Pashto | South-West Asia,AfghanistanandPakistan | Perso-Arabic | ګ is interchangeable with گ. Also, the glyphs ی and ې are often replaced with ے in Pakistan. |

| Pegon script | 35 | ڎڟڠڤڮۑ | Naskh | Javanese,Sundanese | South-East Asia (Indonesia) | Perso-Arabic | |

| Persian | 32 | پچژگ | NaskhandNastaliq | Persian(Farsi) | West Asia (Iran etc. ) | Arabic | Also known as Perso-Arabic. |

| Shahmukhi | 41 | ݪݨ | Nastaliq | Punjabi | South Asia (Pakistan) | Perso-Arabic | |

| Saraiki | 45 | ٻڄݙڳ | Nastaliq | Saraiki | South Asia (Pakistan) | Urdu | |

| Sindhi | 52 | ڪڳڱگک پڀٻٽٿٺ ڻڦڇچڄڃ ھڙڌڏڎڍڊ |

Naskh | Sindhi | South Asia (Pakistan) | Perso-Arabic | |

| Sorabe | 28 | Naskh | Malagasy | Madagascar | Arabic | ||

| Soranî | 33 | ڕڤڵۆێ | Naskh | Kurdish languages | Middle-East | Perso-Arabic | Vowels are mandatory, i.e. Alpha bet |

| Swahili Arabic script | 28 | Naskh | Swahili | Western and Southern Africa | Arabic | ||

| İske imlâ | 35 | ۋ | Naskh | Tatar | Volga region | Chagatai | Used prior to 1920. |

| Ottoman Turkish | 32 | ﭖﭺﮊﮒﯓئەی | Ottoman Turkish | Ottoman Empire | Chagatai | Official until 1928 | |

| Urdu | 39+ (see notes) |

ٹڈڑںہھے (see notes) |

Nastaliq | Urdu | South Asia | Perso-Arabic | 58[citation needed]letters including digraphs representingaspirated consonants. بھپھتھٹھجھچھدھڈھکھگھ |

| Uyghur | 32 | ئائەھئوئۇئۆئۈۋئېئى | Naskh | Uyghur | China, Central Asia | Chagatai | Reform of older Arabic-script Uyghur orthography that was used prior to the 1950s. Vowels are mandatory, i.e. Alpha bet |

| Wolofal | 33 | ݖگݧݝݒ | Naskh | Wolof | West Africa | Arabic,however, borrows at least one glyph fromPerso-Arabic | |

| Xiao'erjing | 36 | ٿس﮲ڞي | Naskh | Sinitic languages | China, Central Asia | Chagatai | Used to write Chinese languages by Muslims living in China such as the Hui people. |

| Yaña imlâ | 29 | ئائەئیئوئۇئھ | Naskh | Tatar | Volga region | İske imlâ Alpha bet | 1920–1927 replaced with Cyrillic |

Current use

[edit]Today Iran, Afghanistan, Pakistan, India, and China are the main non-Arabic speaking states using the Arabic Alpha bet to write one or more official national languages, includingAzerbaijani,Baluchi,Brahui,Persian,Pashto,Central Kurdish,Urdu,Sindhi,Kashmiri,PunjabiandUyghur.[citation needed]

An Arabic Alpha bet is currently used for the following languages:[citation needed]

Middle East and Central Asia

[edit]- Arabic

- Garshuni(or Karshuni) originated in the 7th century, when Arabic became the dominant spoken language in theFertile Crescent,but Arabic script was not yet fully developed or widely read, and so theSyriac Alpha betwas used. There is evidence that writing Arabic in this other set of letters (known as Garshuni) influenced the style of modern Arabic script. After this initial period, Garshuni writing has continued to the present day among someSyriacChristian communities in the Arabic-speaking regions of theLevantandMesopotamia.

- Kazakhin Kazakhstan, China,IranandAfghanistan

- Kurdishin NorthernIraqand NorthwestIran.(InTurkeyandSyriatheLatin scriptis used for Kurdish)

- Kyrgyzby its 150,000 speakers in theXin gian g Uyghur Autonomous Regionin northwesternChina,Pakistan,KyrgyzstanandAfghanistan

- Turkmenin Turkmenistan,[verification needed]Afghanistan and Iran

- Uzbekin Uzbekistan[verification needed]and Afghanistan

- PersianinIranian PersianandDariin Afghanistan. It had former use in Tajikistan but is no longer used inStandard Tajik

- Baluchiin Iran, in Pakistan's Balochistan region, Afghanistan and Oman[16]

- Southwestern Iranian languagesasLori dialectsandBakhtiari language[17][18]

- Pashtoin Afghanistan and Pakistan, and Tajikistan

- Uyghurchanged to Latin script in 1969 and back to a simplified, fully voweled Arabic script in 1983

- Judeo-Arabic languages

East Asia

[edit]- TheChinese languageis written by someHuiin the Arabic-derivedXiao'erjingAlpha bet (see alsoSini (script))

- The TurkicSalar languageis written by someSalarin the Arabic Alpha bet

- Uyghur Alpha bet

South Asia

[edit]- BalochiinPakistanandIran

- DariinAfghanistan

- KashmiriinIndiaandPakistan(also written inSharadaandDevanagarialthough Kashmiri is more commonly written in Perso-Arabic Script)

- Pashtoin Afghanistan and Pakistan

- Khowarin Northern Pakistan, also uses the Latin script

- Punjabi(Shahmukhi) in Pakistan, also written in theBrahmicscript known asGurmukhiin India

- Saraiki,written with a modified Arabic script – that has 45 letters

- Sindhi,a British commissioner inSindhon August 29, 1857, ordered to change Arabic script[vague],[20]also written inDevanagariin India

- Aer language[21]

- Bhadrawahi language[22]

- Ladakhi(India), although it is more commonly written using theTibetan script

- Balti(aSino-Tibetan language), also rarely written in the Tibetan script

- Brahui languagein Pakistan and Afghanistan[23]

- Burushaskior Burusho language, a language isolated to Pakistan.

- Urduin Pakistan (and historically several otherHindustani languages). Urdu is one of several official languages in the states ofJammu and Kashmir,Delhi,Uttar Pradesh,Bihar,Jharkhand,West BengalandTelangana.

- Dogri,spoken by about five million people in India and Pakistan, chiefly in the Jammu region of Jammu and Kashmir and inHimachal Pradesh,but also in northern Punjab, although Dogri is more commonly written in Devanagari

- Arwi language(a mixture of Arabic and Tamil) uses the Arabic script together with the addition of 13 letters. It is mainly used inSri Lankaand the South Indian state ofTamil Nadufor religious purposes.Arwi languageis the language of Tamil Muslims

- Arabi MalayalamisMalayalamwritten in the Arabic script. The script has particular letters to represent the peculiar sounds of Malayalam. This script is mainly used inmadrasasof the South Indian state ofKeralaand ofLakshadweep.

- Rohingya language(Ruáingga) is a language spoken by the Rohingya people ofRakhine State, formerly known as Arakan(Rakhine),Burma(Myanmar). It is similar toChittagonian languagein neighboring Bangladesh[24]and sometimes written using the Roman script, or an Arabic-derived script known asHanifi

- Ishkashimi language(Ishkashimi) inAfghanistan

Southeast Asia

[edit]- Malayin the Arabic script known asJawi.In some cases it can be seen in the signboards of shops and market stalls. Particularly in Brunei, Jawi is used in terms of writing or reading for Islamic religious educational programs in primary school, secondary school, college, or even higher educational institutes such as universities. In addition, some television programming uses Jawi, such as announcements, advertisements, news, social programs or Islamic programs

- co-official inBrunei

- Malaysiabut co-official inKelantanandKedah,Islamic states in Malaysia

- Indonesia,Jawi script is co-used withLatinin provinces ofAceh,Riau,Riau IslandsandJambi.TheJavanese,MadureseandSundanesealso use another Arabic variant, thePegonin Islamic writings andpesantrencommunity.

- Southern Thailand

- Predominantly Muslim areas of thePhilippines(especiallyMaguindanaonandTausug)

- Ida'an language(also Idahan) a Malayo-Polynesian language spoken by the Ida'an people ofSabah,Malaysia[25]

- Cham languagein Cambodia besidesWestern Cham script.

Europe

[edit]Africa

[edit]- North Africa

- Arabic

- Berber languageshave often been written inan adaptation of the Arabic Alpha bet.The use of the Arabic Alpha bet, as well as the competingLatinandTifinaghscripts, has political connotations

- Tuareg language,(sometimes called Tamasheq) which is also a Berber language

- Coptic languageof Egyptians as Coptic text written in Arabic letters[26]

- Northeast Africa

- Bedawi or Beja,mainly in northeasternSudan

- Wadaad's writing,used inSomalia

- Nubian languages

- Dongolawi languageor Andaandi language of Nubia, in the Nile Vale of northern Sudan

- Nobiin language,the largest Nubian language (previously known by the geographic terms Mahas and Fadicca/Fiadicca) is not yet standardized, being written variously in bothLatinizedand Arabic scripts; also, there have been recent efforts to revive the Old Nubian Alpha bet.[27][28]

- Fur languageof Darfur, Sudan

- Southeast Africa

- Comorian,in theComoros,currently side by side with theLatin Alpha bet(neither is official)

- Swahili,was originally written in Arabic Alpha bet, Swahili orthography is now based on the Latin Alpha bet that was introduced by Christian missionaries and colonial administrators

- West Africa

- Zarma languageof theSonghay family.It is the language of the southwestern lobe of the West African nation of Niger, and it is the second leading language of Niger, after Hausa, which is spoken in south central Niger[29]

- Tadaksahakis a Songhay language spoken by the pastoralist Idaksahak of the Ménaka area ofMali[30]

- Hausa languageuses an adaptation of the Arabic script known asAjami,for many purposes, especially religious, but including newspapers, mass mobilization posters and public information[31]

- Dyula languageis aMandé languagespoken in Burkina Faso, Côte d'Ivoire and Mali.[32]

- Jola-Fonyi languageof theCasamanceregion ofSenegal[33]

- Balanta languagea Bak language of west Africa spoken by the Balanta people andBalanta-Ganjadialect in Senegal

- Mandinka,widely but unofficially (known as Ajami), (another non-Latin script used is theN'Ko script)

- Fula,especially the Pular of Guinea (known as Ajami)

- Wolof(atzaouiaschools), known asWolofal.

- Yoruba,earliest attested history of use since 17th century, however earliest verifiable history of use dates to the 19th century. Yoruba Ajami used in Muslim praise verse, poetry, personal and esoteric use[34]

- Arabic script outside Africa

- In writings of African American slaves

- Writings of byOmar Ibn Said(1770–1864) of Senegal[35]

- TheBilali Documentalso known as Bilali Muhammad Document is a handwritten, Arabic manuscript[36]on West African Islamic law. It was written by Bilali Mohammet in the 19th century. The document is currently housed in the library at the University of Georgia

- Letter written byAyuba Suleiman Diallo(1701–1773)

- Arabic Text From 1768[37]

- Letter written byAbdul Rahman Ibrahima Sori(1762–1829)

- In writings of African American slaves

Former use

[edit]With the establishment ofMuslim rulein thesubcontinent,one or more forms of the Arabic script were incorporated among the assortment of scripts used for writing native languages.[38]In the 20th century, the Arabic script was generally replaced by theLatin Alpha betin theBalkans,[dubious–discuss]parts ofSub-Saharan Africa,andSoutheast Asia,while in theSoviet Union,after a brief period ofLatinisation,[39]use ofCyrillicwas mandated.Turkeychanged to the Latin Alpha bet in 1928 as part of an internal Westernizing revolution. After the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, many of the Turkic languages of the ex-USSR attempted to follow Turkey's lead and convert to a Turkish-style Latin Alpha bet. However, renewed use of the Arabic Alpha bet has occurred to a limited extent inTajikistan,whose language's close resemblance toPersianallows direct use of publications from Afghanistan and Iran.[40]

Africa

[edit]- Afrikaans(as it was first written among the "Cape Malays",seeArabic Afrikaans)

- Berberin North Africa, particularlyShilhainMorocco(still being considered, along withTifinaghand Latin, forCentral Atlas Tamazight)

- Frenchby theArabsandBerbersin Algeria and other parts of North Africa during the French colonial period

- Harari,by theHarari peopleof theHarari RegioninEthiopia.Now uses theGeʻezandLatin Alpha bets

- For the West African languages—Hausa,Fula,Mandinka,Wolofand others—the Latin Alpha bet has officially replaced Arabic transcriptions for use in literacy and education

- KinyarwandainRwanda

- KirundiinBurundi

- MalagasyinMadagascar(script known asSorabe)

- Nubian

- ShonainZimbabwe

- Somali(seewadaad'sArabic) has mostly used theLatin Alpha betsince 1972

- Songhayin West Africa, particularly inTimbuktu

- Swahili(has used theLatin Alpha betsince the 19th century)

- Yorubain West Africa

Europe

[edit]- AlbaniancalledElifbaja shqip

- Aljamiado(Mozarabic,Berber,Aragonese,Portuguese[citation needed],Ladino,andSpanish,during and residually after the Muslim rule in the Iberian peninsula)

- Belarusian(among ethnicTatars;seeBelarusian Arabic Alpha bet)

- Bosnian(only for literary purposes; currently written in theLatin Alpha bet;Text example:مۉلٖىمۉ سه تهبٖى بۉژه =Molimo se tebi, Bože(We pray to you, O God); seeArebica)

- Crimean Tatar

- Greekin certain areas inGreeceandAnatolia.In particular,Cappadocian Greekwritten inPerso-Arabic

- Polish(among ethnicLipka Tatars)

Central Asia and Caucasus

[edit]- Adyghe languagealso known as West Circassian, is an official languages of the Republic ofAdygeain the Russian Federation. It used Arabic Alpha bet before 1927

- Avaras well as other languages ofDaghestan:Nogai,Kumyk,Lezgian,LakandDargwa

- AzeriinAzerbaijan(now written in theLatin Alpha betandCyrillic scriptinAzerbaijan)

- Bashkir(officially for some years from theOctober Revolutionof 1917 until 1928, changed to Latin, now uses the Cyrillic script)

- ChaghatayacrossCentral Asia

- Chechen(sporadically from the adoption of Islam; officially from 1917 until 1928)[41]

- Circassianand some other members of theAbkhaz–Adyghe familyin the westernCaucasusand sporadically – in the countries of Middle East, like Syria

- Ingush

- Karachay-Balkarin the central Caucasus

- Karakalpak

- KazakhinKazakhstan(until the 1930s, changed to Latin, currently using Cyrillic, phasing in Latin)

- KyrgyzinKyrgyzstan(until the 1930s, changed to Latin, now uses the Cyrillic script)

- Mandarin ChineseandDungan,among theHui people(script known asXiao'erjing)

- Ottoman Turkish

- Tatin South-Eastern Caucasus

- Tatarbefore 1928 (changed to LatinYañalif), reformed in the 1880s (İske imlâ), 1918 (Yaña imlâ– with the omission of some letters)

- TurkmeninTurkmenistan(changed to Latin in 1929, then to the Cyrillic script, then back to Latin in 1991)

- UzbekinUzbekistan(changed to Latin, then to the Cyrillic script, then back to Latin in 1991)

- SomeNortheast Caucasian languagesof the Muslim peoples of theUSSRbetween 1918 and 1928 (many also earlier), includingChechen,Lak,etc. After 1928, their script became Latin, then later[when?]Cyrillic[citation needed]

South and Southeast Asia

[edit]- AcehneseinSumatra,Indonesia

- AssameseinAssam,India

- BanjareseinKalimantan,Indonesia

- BengaliinBengal,Arabic scripts have been used historically in places likeChittagongandWest Bengalamong other places. SeeDobhashifor further information.

- Maguindanaonin thePhilippines

- MalayinMalaysia,SingaporeandIndonesia.Although Malay speakers inBruneiandSouthern Thailandstill use the script on a daily basis

- Minangkabauin Sumatra, Indonesia

- Pegon scriptofJavanese,MadureseandSundanesein Indonesia, used only in Islamic schools and institutions

- Tausugin thePhilippines,Malaysia,andIndonesiait can be used in Islamic schools inthe Philippines

- Yakanpracticed in Islamic schools inBasilan

Middle East

[edit]- Hebrewwas written in Arabic letters in a number of places in the past[42][43]

- Northern Kurdishin Turkey and Syria was written in Arabic script until 1932, when a modifiedKurdish Latin Alpha betwas introduced byJaladat Ali Badirkhanin Syria

- Turkishin theOttoman Empirewas written in Arabic script untilMustafa Kemal Atatürkdeclared the change toLatin scriptin 1928. This form of Turkish is now known asOttoman Turkishand is held by many to be a different language, due to its much higher percentage of Persian and Arabicloanwords(Ottoman Turkish Alpha bet)

Unicode

[edit]As of Unicode 15.1, the following ranges encode Arabic characters:

- Arabic(0600–06FF)

- Arabic Supplement(0750–077F)

- Arabic Extended-A(08A0–08FF)

- Arabic Extended-B(0870–089F)

- Arabic Extended-C(10EC0–10EFF)

- Arabic Presentation Forms-A(FB50–FDFF)

- Arabic Presentation Forms-B(FE70–FEFF)

- Arabic Mathematical Alphabetic Symbols(1EE00–1EEFF)

- Rumi Numeral Symbols(10E60–10E7F)

- Indic Siyaq Numbers(1EC70–1ECBF)

- Ottoman Siyaq Numbers(1ED00–1ED4F)

Additional letters used in other languages

[edit]| Language family | Austron. | Dravid | Turkic | Indic | Iranian[a] | Germanic | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Language/script | Jawi | Pegon | Arwi | Azeri | Ottoman | Tatar | Uyghur | Sindhi | Punjabi | Urdu | Persian | Balochi | Pashto | Kurdish | Afrikaans |

| /t͡ʃ/ | چ | ||||||||||||||

| /ʒ/ | ∅ | ژ | |||||||||||||

| /p/ | ڤ | ڣ | پ | ||||||||||||

| /g/ | ݢ | ؼ | ࢴ | ق | گ | ||||||||||

| /v/ | ۏ | و | ۋ | و | ∅ | ڤ | |||||||||

| /ŋ/ | ڠ | ࢳ | ∅ | ڭ | ڱ | ن | ∅ | ڠ | |||||||

| /ɲ/ | ڽ | ۑ | ݧ | ∅ | ڃ | ن | ∅ | ||||||||

| /ɳ/ | ∅ | ڹ | ∅ | ڻ | ݨ | ن | ∅ | ڼ | ∅ | ||||||

| Letter orDigraph[A] | Use & Pronunciation | Unicode | i'jam& other additions | Shape | Similar Arabic Letter(s) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| U+ | [B] | [C] | above | below | |||||||

| پ | پـ ـپـ ـپ | Pe,used to represent the phoneme/p/inPersian,Pashto,Punjabi,Khowar,Sindhi,Urdu,Kurdish,Kashmiri;it can be used in Arabic to describe the phoneme/p/otherwise it is normalized to/b/ب e.g. پول Paul also written بول | U+067E | ﮹ | none | 3 dots | ٮ | ب | |||

| ݐ | ݐـ ـݐـ ـݐ | used to represent the equivalent of the Latin letterƳ(palatalizedglottal stop/ʔʲ/) in some African languages such asFulfulde. | U+0750 | ﮳﮳﮳ | none | 3 dots (horizontal) |

ٮ | ب | |||

| ٻ | ٻـ ـٻـ ـٻ | B̤ē,used to represent avoiced bilabial implosive/ɓ/inHausa,SindhiandSaraiki. | U+067B | ﮾ | none | 2 dots (vertically) |

ٮ | ب | |||

| ڀ | ڀـ ـڀـ ـڀ | represents an aspiratedvoiced bilabial plosive/bʱ/inSindhi. | U+0680 | ﮻ | none | 4 dots | ٮ | ب | |||

| ٺ | ٺـ ـٺـ ـٺ | Ṭhē,represents the aspiratedvoiceless retroflex plosive/ʈʰ/inSindhi. | U+067A | ﮽ | 2 dots (vertically) |

none | ٮ | ت | |||

| ټ | ټـ ـټـ ـټ | Ṭē,used to represent the phoneme/ʈ/inPashto. | U+067C | ﮿ | ﮴ | 2 dots | ring | ٮ | ت | ||

| ٽ | ٽـ ـٽـ ـٽ | Ṭe,used to represent the phoneme (avoiceless retroflex plosive/ʈ/) inSindhi | U+067D | ﮸ | 3 dots (inverted) |

none | ٮ | ت | |||

| ﭦ | ٹـ ـٹـ ـٹ | Ṭe,used to represent Ṭ (avoiceless retroflex plosive/ʈ/) inPunjabi,Kashmiri,Urdu. | U+0679 | ◌ؕ | small ط |

none | ٮ | ت | |||

| ٿ | ٿـ ـٿـ ـٿ | Teheh,used in Sindhi and Rajasthani (when written in Sindhi Alpha bet); used to represent the phoneme/t͡ɕʰ/(pinyinq) in ChineseXiao'erjing. | U+067F | ﮺ | 4 dots | none | ٮ | ت | |||

| ڄ | ڄـ ـڄـ ـڄ | represents the "c"voiceless dental affricate/t͡s/phoneme inBosnian | U+0684 | ﮾ | none | 2 dots (vertically) |

ح | ج | |||

| ڃ | ڃـ ـڃـ ـڃ | represents the "ć"voiceless alveolo-palatal affricate/t͡ɕ/phoneme inBosnian. | U+0683 | ﮵ | none | 2 dots | ح | ح ج | |||

| چ | چـ ـچـ ـچ | Che,used to represent/t͡ʃ/( "ch" ). It is used inPersian,Pashto,Punjabi,Urdu,KashmiriandKurdish./ʒ/in Egypt. | U+0686 | ﮹ | none | 3 dots | ح | ج | |||

| څ | څـ ـڅـ ـڅ | Ce,used to represent the phoneme/t͡s/inPashto. | U+0685 | ﮶ | 3 dots | none | ح | ج خ ح | |||

| ݗ | ݗـ ـݗـ ـݗ | represents the "đ"voiced alveolo-palatal affricate/d͡ʑ/phoneme inBosnian. | U+0757 | ﮴ | 2 dots | none | ح | ح | |||

| ځ | ځـ ـځـ ـځ | Źim,used to represent the phoneme/d͡z/inPashto. | U+0681 | ◌ٔ | Hamza | none | ح | ج خ ح | |||

| ݙ | ݙ ـݙ | used inSaraikito represent aVoiced alveolar implosive/ɗ̢/. | U+0759 | ﯀ | ﮾ | small ط |

2 dots (vertically) |

د | د | ||

| ڊ | ڊ ـڊ | used inSaraikito represent avoiced retroflex implosive/ᶑ/. | U+068A | ﮳ | none | 1 dot | د | د | |||

| ڈ | ڈ ـڈ | Ḍal,used to represent a Ḍ (avoiced retroflex plosive/ɖ/) inPunjabi,KashmiriandUrdu. | U+0688 | ◌ؕ | smallط | none | د | د | |||

| ڌ | ڌ ـڌ | Dhal,used to represent the phoneme/d̪ʱ/inSindhi | U+068C | ﮴ | 2 dots | none | د | د | |||

| ډ | ډ ـډ | Ḍal,used to represent the phoneme/ɖ/inPashto. | U+0689 | ﮿ | none | ring | د | د | |||

| ڑ | ڑ ـڑ | Ṛe,represents aretroflex flap/ɽ/inPunjabiandUrdu. | U+0691 | ◌ؕ | smallط | none | ر | ر | |||

| ړ | ړ ـړ | Ṛe,used to represent aretroflex lateral flapinPashto. | U+0693 | ﮿ | none | ring | ر | ر | |||

| ݫ | ݫ ـݫ | used inOrmurito represent avoiced alveolo-palatal fricative/ʑ/,as well as inTorwali. | U+076B | ﮽ | 2 dots (vertically) |

none | ر | ر | |||

| ژ | ژ ـژ | Že / zhe,used to represent thevoiced postalveolar fricative/ʒ/in,Persian,Pashto,Kurdish,Urdu,PunjabiandUyghur. | U+0698 | ﮶ | 3 dots | none | ر | ز | |||

| ږ | ږ ـږ | Ǵe / ẓ̌e,used to represent the phoneme/ʐ//ɡ//ʝ/inPashto. | U+0696 | ﮲ | ﮳ | 1 dot | 1 dot | ر | ز | ||

| ڕ | ڕ ـڕ | used inKurdishto represent rr/r/inSoranî dialect. | U+0695 | ٚ | none | V pointing down | ر | ر | |||

| ݭ | ݭـ ـݭـ ـݭ | used inKalamito represent avoiceless retroflex fricative/ʂ/,and inOrmurito represent a voiceless alveolo-palatal fricative /ɕ/. | U+076D | ﮽ | 2 dotsvertically | none | س | س | |||

| ݜ | ݜـ ـݜـ ـݜ | used inShinato represent avoiceless retroflex fricative/ʂ/. | U+075C | ﮺ | 4 dots | none | س | ش س | |||

| ښ | ښـ ـښـ ـښ | X̌īn / ṣ̌īn,used to represent the phoneme/x//ʂ//ç/inPashto. | U+069A | ﮲ | ﮳ | 1 dot | 1 dot | س | ش س | ||

| ڜ | ڜـ ـڜـ ـڜ | Unofficially used to represent Spanish words with/t͡ʃ/in Morocco. | U+069C | ﮶ | ﮹ | 3 dots | 3 dots | س | ش س | ||

| ڨ | ڨـ ـڨـ ـڨ | Ga,used to represent thevoiced velar plosive/ɡ/inAlgerianandTunisian. | U+06A8 | ﮶ | 3 dots | none | ٯ | ق | |||

| گ | گـ ـگـ ـگ | Gaf,represents avoiced velar plosive/ɡ/inPersian,Pashto,Punjabi,Kyrgyz,Kazakh,Kurdish,Uyghur,Mesopotamian Arabic,UrduandOttoman Turkish. | U+06AF | line | horizontal line | none | گ | ك | |||

| ګ | ګـ ـګـ ـګ | Gaf,used to represent the phoneme/ɡ/inPashto. | U+06AB | ﮿ | ring | none | ک | ك | |||

| ݢ | ݢـ ـݢـ ـݢ | Gaf,represents avoiced velar plosive/ɡ/in theJawi scriptofMalay. | U+0762 | ﮲ | 1 dot | none | ک | ك | |||

| ڬ | ڬـ ـڬـ ـڬ | U+06AC | ﮲ | 1 dot | none | ك | ك | ||||

| ؼ | ؼـ ـؼـ ـؼ | Gaf,represents avoiced velar plosive/ɡ/in thePegon scriptofIndonesian. | U+08B4 | ﮳ | none | 3 dots | ک | ك | |||

| ڭ | ڭـ ـڭـ ـڭ | Ng,used to represent the/ŋ/phone inOttoman Turkish,Kazakh,Kyrgyz,andUyghur,and to unofficially represent the/ɡ/inMoroccoand in many dialects ofAlgerian. | U+06AD | ﮶ | 3 dots | none | ك | ك | |||

| أي | أيـ ـأيـ ـأي | Ee,used to represent the phoneme/eː/inSomali. | U+0623U+064A | ◌ٔ | ﮵ | Hamza | 2 dots | اى | أ+ي | ||

| ئ | ئـ ـئـ ـئ | E,used to represent the phoneme/e/inSomali. | U+0626 | ◌ٔ | Hamza | none | ى | ي ی | |||

| ىٓ | ىٓـ ـىٓـ ـىٓ | Ii,used to represent the phoneme/iː/inSomaliandSaraiki. | U+0649U+0653 | ◌ٓ | Madda | none | ى | ي | |||

| ؤ | ؤ ـؤ | O,used to represent the phoneme/o/inSomali. | U+0624 | ◌ٔ | Hamza | none | و | ؤ | |||

| ۅ | ۅ ـۅ | Ö,used to represent the phoneme/ø/inKyrgyz. | U+0624 | ◌̵ | Strikethrough[D] | none | و | و | |||

| ې | ېـ ـېـ ـې | Pasta Ye,used to represent the phoneme/e/inPashtoandUyghur. | U+06D0 | ﮾ | none | 2 dotsvertical | ى | ي | |||

| ی | یـ ـیـ ـی | Nārīna Ye,used to represent the phoneme [ɑj] and phoneme/j/inPashto. | U+06CC | ﮵ | 2 dots (start + mid) |

none | ى | ي | |||

| ۍ | ـۍ | end only |

X̌əźīna ye Ye,used to represent the phoneme [əi] inPashto. | U+06CD | line | horizontal line |

none | ى | ي | ||

| ئ | ئـ ـئـ ـئ | Fāiliya Ye,used to represent the phoneme [əi] and/j/inPashto,Punjabi,SaraikiandUrdu | U+0626 | ◌ٔ | Hamza | none | ى | ي ى | |||

| أو | أو ـأو | Oo,used to represent the phoneme/oː/inSomali. | U+0623U+0648 | ◌ٔ | Hamza | none | او | أ+و | |||

| ﻭٓ | ﻭٓ ـﻭٓ | Uu,used to represent the phoneme/uː/inSomali. | ﻭ +◌ٓU+0648U+0653 | ◌ٓ | Madda | none | و | ﻭ+◌ٓ | |||

| ڳ | ڳـ ـڳـ ـڳ | represents avoiced velar implosive/ɠ/inSindhiandSaraiki | U+06B1 | ﮾ | horizontal line |

2 dots | گ | ك | |||

| ڱ | ڱـ ـڱـ ـڱ | represents theVelar nasal/ŋ/phoneme inSindhi. | U+06B1 | ﮴ | 2 dots +horizontal line |

none | گ | ك | |||

| ک | کـ ـکـ ـک | Khē,represents/kʰ/inSindhi. | U+06A9 | none | none | none | ک | ك | |||

| ڪ | ڪـ ـڪـ ـڪ | "Swash kāf" is a stylistic variant ofك in Arabic, but represents un-aspirated/k/inSindhi. | U+06AA | none | none | none | ڪ | كorڪ | |||

| ݣ | ݣـ ـݣـ ـݣ | used to represent the phoneme/ŋ/(pinyinng) inChinese. | U+0763 | ﮹ | none | 3 dots | ک | ك | |||

| ڼ | ڼـ ـڼـ ـڼ | represents theretroflex nasal/ɳ/phoneme inPashto. | U+06BC | ﮲ | ﮿ | 1 dot | ring | ں | ن | ||

| ڻ | ڻـ ـڻـ ـڻ | represents theretroflex nasal/ɳ/phoneme inSindhi. | U+06BB | ◌ؕ | smallط | none | ں | ن | |||

| ݨ | ݨـ ـݨـ ـݨ | used inPunjabito represent/ɳ/andSaraikito represent/ɲ/. | U+0768 | ﮲ | ﯀ | 1 dot + smallط | none | ں | ن | ||

| ڽ | ڽـ ـڽـ ـڽ | Nya/ɲ/in theJawi script. | U+06BD | ﮶ | 3 dots | none | ں | ن | |||

| ۑ | ۑـ ـۑـ ـۑ | Nya/ɲ/in thePegon script. | U+06D1 | ﮹ | none | 3 dots | ى | ى | |||

| ڠ | ڠـ ـڠـ ـڠ | Nga/ŋ/in theJawi scriptandPegon script. | U+06A0 | ﮶ | 3 dots | none | ع | غ | |||

| ݪ | ݪـ ـݪـ ـݪ | used inMarwarito represent aretroflex lateral flap/ɺ̢/,and inKalamito represent avoiceless lateral fricative/ɬ/. | U+076A | line | horizontal line |

none | ل | ل | |||

| ࣇ | ࣇ ࣇ ࣇ | ࣇ– or alternately typeset asلؕ – is used inPunjabito representvoiced retroflex lateral approximant/ɭ/[44] | U+08C7 | ◌ؕ | smallط | none | ل | ل | |||

| لؕ | لؕـ ـلؕـ ـلؕ | U+0644U+0615 | |||||||||

| ڥ | ڥـ ـڥـ ـڥ | Vi,used inAlgerian ArabicandTunisian Arabicwhen written in Arabic script to represent the sound/v/(unofficial). | U+06A5 | ﮹ | none | 3 dots | ڡ | ف | |||

| ڤ | ڤـ ـڤـ ـڤ | Ve,used in by someArabicspeakers to represent the phoneme /v/ in loanwords, and in theKurdish languagewhen written in Arabic script to represent the sound/v/.Also used aspa/p/in theJawi scriptandPegon script. | U+06A4 | ﮶ | 3 dots | none | ڡ | ف | |||

| ۏ | ۏ ـۏ | Vain theJawi script. | U+06CF | ﮲ | 1 dot | none | و | و | |||

| ۋ | ۋ ـۋ | represents avoiced labiodental fricative/v/inKyrgyz,Uyghur,and Old Tatar; and/w,ʊw,ʉw/inKazakh;also formerly used inNogai. | U+06CB | ﮶ | 3 dots | none | و | و | |||

| ۆ | ۆ ـۆ | represents "O"/o/inKurdish,and inUyghurit represents the sound similar to the Frencheuandœu/ø/sound. It represents the "у"close back rounded vowel/u/phoneme inBosnian. | U+06C6 | ◌ٚ | V pointing down | none | و | و | |||

| ۇ | ۇ ـۇ | U,used to represents theClose back rounded vowel/u/phoneme inAzerbaijani,Kazakh,KyrgyzandUyghur. | U+06C7 | ◌ُ | Damma[E] | none | و | و | |||

| ێ | ێـ ـێـ ـێ | represents Ê or É/e/inKurdish. | U+06CE | ◌ٚ | V pointing down | 2 dots (start + mid) |

ى | ي | |||

| ھ ھ |

ھـ ـھـ ـھ ھھھ |

Do-chashmi he(two-eyed hāʼ), used in digraphs for aspiration/ʰ/and breathy voice/ʱ/inPunjabiandUrdu.Also used to represent/h/inKazakh,SoraniandUyghur.[F] | U+06BE | none | none | none | ھ | ه | |||

| ە | ە ـە | Ae,used represent/æ/and/ɛ/inKazakh,SoraniandUyghur. | U+06D5 | none | none | none | ھ | إ | |||

| ے | ـے | end only |

Baṛī ye('bigyāʼ'), is a stylistic variant of ي in Arabic, but represents "ai" or "e"/ɛː/,/eː/inUrduandPunjabi. | U+06D2 | none | none | none | ے | ي | ||

| ڞ | ڞـ ـڞـ ـڞ | used to represent the phoneme/tsʰ/(pinyinc) inChinese. | U+069E | ﮶ | 3 dots | none | ص | ص ض | |||

| ط | طـ ـطـ ـط | used to represent the phoneme/t͡s/(pinyinz) inChinese. | U+0637 | ط | ط | ||||||

| ۉ | ۉ ـۉ | represents the "o"open-mid back rounded vowel/ɔ/phoneme inBosnian.Also used to represent /ø/ inKyrgyz. | U+06C9 | ◌ٛ | V pointing up | none | و | و | |||

| ݩ | ݩـ ـݩـ ـݩ | represents the "nj"palatal nasal/ɲ/phoneme inBosnian. | U+0769 | ﮲ | ◌ٚ | 1 dot V pointing down |

none | ں | ن | ||

| ڵ | ڵـ ـڵـ ـڵ | used inKurdishto represent ll/ɫ/inSoranî dialect. | U+06B5 | ◌ٚ | V pointing down | none | ل | ل | |||

| ڵ | ڵـ ـڵـ ـڵ | represents the "lj"palatal lateral approximant/ʎ/phoneme inBosnian. | U+06B5 | ◌ٚ | V pointing down | none | ل | ل | |||

| اٖى | اٖىـ ـاٖىـ ـاٖى | represents the "i"close front unrounded vowel/i/phoneme inBosnian. | U+0627U+0656U+0649 | ◌ٖ | Alef | none | اى | اٖ+ى | |||

- ^From right: start, middle, end, and isolated forms.

- ^Joined to the letter, closest to the letter, on the first letter, or above.

- ^Further away from the letter, or on the second letter, or below.

- ^A variant that end up with loop also exists.

- ^Although the letter also known asWaw with Damma,some publications and fonts features filled Damma that looks similar to comma.

- ^Shown inNaskh(top) andNastaliq(bottom) styles. The Nastaliq version of the connected forms are connected to each other, because the tatweel characterU+0640used to show the other forms does not work in manyNastaliq fonts.

Letter construction

[edit]Most languages that use Alpha bets based on the Arabic Alpha bet use the same base shapes. Most additional letters in languages that use Alpha bets based on the Arabic Alpha bet are built by adding (or removing) diacritics to existing Arabic letters. Some stylistic variants in Arabic have distinct meanings in other languages. For example, variant forms ofkāfك ک ڪ are used in some languages and sometimes have specific usages. In Urdu and some neighbouring languages, the letter Hā has diverged into two formsھdō-čašmī hēandہ ہـ ـہـ ـہgōl hē,[45]while a variant form ofيyāreferred to asbaṛī yēے is used at the end of some words.[45]

Table of letter components

[edit]See also

[edit]- Arabic (Unicode block)

- Eastern Arabic numerals(digit shapes commonly used with Arabic script)

- History of the Arabic Alpha bet

- Transliteration of Arabic

- Xiao'erjing

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^Daniels, Peter T.;Bright, William,eds. (1996).The World's Writing Systems.Oxford University Press, Inc. p. 559.ISBN978-0195079937.

- ^"Arabic Alphabet".Encyclopædia Britannica online.Archivedfrom the original on 26 April 2015.Retrieved16 May2015.

- ^Vaughan, Don."The World's 5 Most Commonly Used Writing Systems".Encyclopædia Britannica.Archivedfrom the original on 29 July 2023.Retrieved29 July2023.

- ^Cham romanization table background. Library of Congress

- ^Mahinnaz Mirdehghan. 2010. Persian, Urdu, and Pashto: A comparative orthographic analysis.Writing Systems ResearchVol. 2, No. 1, 9–23.

- ^"Exposición Virtual. Biblioteca Nacional de España".Bne.es. Archived fromthe originalon 18 February 2012.Retrieved6 April2012.

- ^Ahmad, Syed Barakat. (11 January 2013).Introduction to Qur'anic script.Routledge.ISBN978-1-136-11138-9.OCLC1124340016.

- ^Gruendler, Beatrice (1993).The Development of the Arabic Scripts: From the Nabatean Era to the First Islamic Century According to Dated Texts.Scholars Press. p. 1.ISBN9781555407100.

- ^Healey, John F.; Smith, G. Rex (13 February 2012)."II - The Origin of the Arabic Alphabet".A Brief Introduction to The Arabic Alphabet.Saqi.ISBN9780863568817.

- ^Senner, Wayne M. (1991).The Origins of Writing.U of Nebraska Press. p. 100.ISBN0803291671.

- ^"Nabataean abjad".omniglot.Retrieved8 March2017.

- ^Naveh, Joseph."Nabatean Language, Script and Inscriptions"(PDF).

- ^Taylor, Jane (2001).Petra and the Lost Kingdom of the Nabataeans.I.B.Tauris. p. 152.ISBN9781860645082.

- ^"Zribi, I., Boujelbane, R., Masmoudi, A., Ellouze, M., Belguith, L., & Habash, N. (2014). A Conventional Orthography for Tunisian Arabic. In Proceedings of the Language Resources and Evaluation Conference (LREC), Reykjavík, Iceland".

- ^Brustad, K. (2000). The syntax of spoken Arabic: A comparative study of Moroccan, Egyptian, Syrian, and Kuwaiti dialects. Georgetown University Press.

- ^"Sayad Zahoor Shah Hashmii".baask.

- ^Sarlak, Riz̤ā (2002)."Dictionary of the Bakhtiari dialect of Chahar-lang".google.eg.

- ^Iran, Mojdeh (5 February 2011)."Bakhtiari Language Video (bak) بختياري ها! خبری مهم"– via Vimeo.

- ^"Ethnologue".Retrieved1 February2020.

- ^"Pakistan should mind all of its languages!".tribune.pk.June 2011.

- ^"Ethnologue".Retrieved1 February2020.

- ^"Ethnologue".Retrieved1 February2020.

- ^"The Bible in Brahui".Worldscriptures.org. Archived fromthe originalon 30 October 2016.Retrieved5 August2013.

- ^"Rohingya Language Book A-Z".Scribd.

- ^"Ida'an".scriptsource.org.

- ^"The Coptic Studies' Corner".stshenouda.Archived fromthe originalon 19 April 2012.Retrieved17 April2012.

- ^"--The Cradle of Nubian Civilisation--".thenubian.net.Archived fromthe originalon 24 April 2012.Retrieved17 April2012.

- ^"2 » AlNuba egypt".19 July 2012. Archived fromthe originalon 19 July 2012.

- ^"Zarma".scriptsource.org.

- ^"Tadaksahak".scriptsource.org.

- ^"Lost Language — Bostonia Summer 2009".bu.edu.

- ^"Dyula".scriptsource.org.

- ^"Jola-Fonyi".scriptsource.org.

- ^"African Arabic-Script Languages Title: From the 'Sacred' to the 'Profane': the Yoruba Ajami Script and the Challenges of a Standard Orthography".ResearchGate.October 2021.

- ^"Ibn Sayyid manuscript".Archived fromthe originalon 8 September 2015.Retrieved27 September2018.

- ^"Muhammad Arabic letter".Archived fromthe originalon 8 September 2015.Retrieved27 September2018.

- ^"Charno Letter".Muslims In America. Archived fromthe originalon 20 May 2013.Retrieved5 August2013.

- ^Asani, Ali S. (2002).Ecstasy and enlightenment: the Ismaili devotional literature of South Asia.Institute of Ismaili Studies. London: I.B. Tauris. p. 124.ISBN1-86064-758-8.OCLC48193876.

- ^Alphabet Transitions – The Latin Script: A New Chronology – Symbol of a New AzerbaijanArchived2007-04-03 at theWayback Machine,by Tamam Bayatly

- ^Sukhail Siddikzoda."Tajik Language: Farsi or Not Farsi?"(PDF).Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 13 June 2006.

- ^"Brief history of writing in Chechen".Archived fromthe originalon 23 December 2008.

- ^p. 20,Samuel Noel Kramer.1986.In the World of Sumer: An Autobiography.Detroit: Wayne State University Press.

- ^J. Blau. 2000. Hebrew written in Arabic characters: An instance of radical change in tradition. (In Hebrew, with English summary). InHeritage and Innovation in Judaeo-Arabic Culture: Proceedings of the Sixth Conference of the Society For Judaeo-Arabic Studies,p. 27-31. Ramat Gan.

- ^Lorna Priest Evans; M. G. Abbas Malik."Proposal to encode ARABIC LETTER LAM WITH SMALL ARABIC LETTER TAH ABOVE in the UCS"(PDF).unicode.org.Retrieved10 May2020.

- ^ab"Urdu Alphabet".user.uni-hannover.de.Archived fromthe originalon 11 September 2019.Retrieved4 May2020.

External links

[edit]- Unicode collation charts—including Arabic letters, sorted by shape

- "Why the right side of your brain doesn't like Arabic"

- Arabic fonts by SIL's Non-Roman Script Initiative

- Alexis Neme and Sébastien Paumier (2019),"Restoring Arabic vowels through omission-tolerant dictionary lookup",Lang Resources & Evaluation,Vol. 53, pp. 1–65.arXiv:1905.04051;doi:10.1007/s10579-019-09464-6

- "Preliminary proposal to encode Arabic Crown Letters"(PDF).Unicode.

- "Proposal to encode Arabic Crown Letters"(PDF).Unicode.