4′33″

| 4'33 " | |

|---|---|

| Modernistcomposition byJohn Cage | |

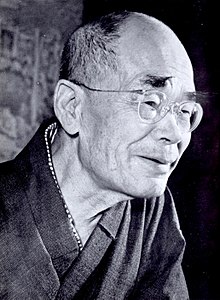

Original Woodstock manuscript of the composition | |

| Year | 1952 |

| Period | Modernist music |

| Duration | 4 minutes and 33 seconds |

| Movements | Three |

| Premiere | |

| Date | August 29, 1952 |

| Performers | David Tudor |

4′33″[a]is amodernistcomposition[b]by AmericanexperimentalcomposerJohn Cage.It was composed in 1952 for any instrument or combination of instruments; the score instructs performers not to play their instruments throughout the three movements. It is divided into three movements,[c]lasting 30 seconds, two minutes and 23 seconds, and one minute and 40 seconds, respectively,[d]although Cage later stated that the movements' durations can be determined by the musician. As indicated by the title, the composition lasts four minutes and 33 seconds and is marked by a period ofsilence,although ambient sounds contribute to the performance.

4'33 "was conceived around 1947–48, while Cage was working on the piano cycleSonatas and Interludes.Many prior musical pieces were largely composed of silence, and silence played a notable role in his prior work, includingSonatas and Interludes.His studies onZen Buddhismduring the late 1940s aboutchance musicled him to acknowledge the value of silence in providing an opportunity to reflect on one's surroundings and psyche. Recent developments incontemporary artalso bolstered Cage's understanding on silence, which he increasingly began to perceive as impossible afterRauschenberg'sWhite Paintingwas first displayed.

4'33 "premiered in 1952 and was met with shock and widespread controversy; many musicologists revisited the very definition of music and questioned whether Cage's work qualified as such. In fact, Cage intended4'33 "to be experimental—to test the audience's attitude to silence and prove that any auditory experience may constitutemusic,seeing that absolute silence[e]cannot exist. Whilst frequently labelled as four minutes and thirty-three seconds of silence, Cage maintains that the ambient noises heard during the performance contribute to the composition. Since this counters the conventional involvement ofharmonyandmelodyin music, many musicologists consider4'33 "to be the birth ofnoise music,and some have likened it toDadaistart.4'33 "also embodies the idea ofmusical indeterminacy,as the silence is subject to the individual's interpretation; thereby, one is encouraged to explore their surroundings and themselves, as stipulated byLacanianism.

4'33 "greatly influenced modernist music, furthering the genres of noise music and silent music, which—whilst still controversial to this day—reverberate among many contemporary musicians. Cage re-explored the idea of silent composition in two later renditions:0'00 "(1962) andOne3(1989). In a 1982 interview, and on numerous other occasions, he stated that4′33″was his most important work.[8]The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musiciansdescribes4′33″as Cage's "most famous and controversial creation". In 2013, Dale Eisinger ofComplexranked the composition eighth in his list of the greatest performance art works.[9]

Background[edit]

The concept[edit]

The first time Cage mentioned the idea of a piece composed entirely of silence was during a 1947 (or 1948) lecture atVassar College,A Composer's Confessions.At this time, he was working on the cycle for pianoSonatas and Interludes.[10]Cage told the audience that he had "several new desires", one of which was:

to compose a piece of uninterrupted silence and sell it toMuzak Co.It will be three or four-and-a-half minutes long—those being the standard lengths of "canned" music and its title will beSilent Prayer.It will open with a single idea which I will attempt to make as seductive as the color and shape and fragrance of a flower. The ending will approach imperceptibility.[11]

Prior to this, silence had played a major role in several of Cage's works composed before4′33″.TheDuet for Two Flutes(1934), composed when Cage was 22, opens with silence, and silence was an important structural element in some of theSonatas and Interludes(1946–48),Music of Changes(1951) andTwo Pastorales(1951). TheConcerto for prepared piano and orchestra(1951) closes with an extended silence, andWaiting(1952), a piano piece composed just a few months before4′33″,consists of long silences framing a single, shortostinatopattern. Furthermore, in his songsThe Wonderful Widow of Eighteen Springs(1942) andA Flower(1950) Cage directs the pianist to play a closed instrument, which may be understood as a metaphor of silence.[12]

However, at the time of its conception, Cage felt that a fully silent piece would be incomprehensible, and was reluctant to write it down: "I didn't wish it to appear, even to me, as something easy to do or as a joke. I wanted to mean it utterly and be able to live with it."[13]PainterAlfred Leslierecalls Cage presenting a "one-minute-of-silence talk" in front of a window during the late 1940s, while visiting Studio 35 atNew York University.[14]

Precursors[edit]

Although he was a pioneer of silent music, Cage was not the first to compose it. Others, especially in the first half of the twentieth century, had already publishedrelated work,which possibly influenced Cage. As early as 1907,Ferruccio Busonidelineated the importance ofatonalityand silence in music:

What comes closest to its original essence in our musical art today are the pause andfermata.Great performance artists and improvisers know how to use this expressive tool to a greater and more extensive extent. The exciting silence between two movements—in this environment, itself, music—is more suggestive than the more definite, but less flexible, sound.[15]

An example is theFuneral March for the Obsequies of a Deaf Man(in French:Marche funèbre composée pour les funérailles d'un grand homme sourd) (1897) byAlphonse Allais,consisting of 24 empty measures.[16]Allais was a companion of his fellow composerErik Satie,[17]and, since Cage admired the latter, theFuneral Marchmay have motivated him to compose4'33 ",but he later wrote that he was not aware of Allais' work at the time.[18]Silent compositions of the twentieth century preceding Cage's include the 'In futurum' movement from theFünf Pittoresken(1919) byErwin Schulhoff—solely comprising rests—[19]andYves Klein'sMonotone–Silence Symphony(1949), in which the second and fourth movements are bare twenty minutes of silence.[17]

Similar ideas had been envisioned in literature. For instance,Harold Acton's prose fableCornelian(1928) mentions a musician conducting "performances consisting largely of silence".[20][21]In 1947, jazz musicianDave Toughjoked that he was writing a play in which "a string quartet is playing the most advanced music ever written. It's made up entirely of rests... Suddenly, the viola man jumps up in a rage and shakes his bow at the first violin. 'Lout', he screams, 'you played that last measure wrong'".[22]

Direct influences[edit]

Zen Buddhism[edit]

Since the late 1940s, Cage had been studyingZen Buddhism,especially through Japanese scholarDaisetz Suzuki,who introduced the field to the Western World. Thereon, he connected sounds in silence to the notions of "unimpededness and interpenetration".[23]In a 1951/1952 lecture, he defined unimpededness as "seeing that in all of space each thing and each human being is at the center", and interpenetration as the view "that each one of the [things and humans at the center] is moving out in all directions penetrating and being penetrated by every other one no matter what the time or what the space", concluding that "each and every thing in all of time and space is related to each and every other thing in all of time and space".[24]

Cage believed that sounds existed in a state of unimpededness, as each one is not hindered by the other due to them being isolated by silence, but also that they interpenetrate each other, since they work in tandem with each other and 'interact' with the silence. Hence, he thought that music is intrinsically an alternation between sound and silence, especially after his visit toHarvard University'sanechoic chamber.[25]He increasingly began to see silence as an integral part of music since it allows for sounds to exist in the first place—to interpenetrate each other. The prevalence of silence in a composition also allowed the opportunity for contemplation on one's psyche and surroundings, reflecting the Zen emphasis onmeditation musicas means to soothe the mind.[26]As he began to realize the impossibility of absolute silence, Cage affirmed the psychological significance of 'lack of sound' in a musical composition:

I've thought of music as a means of changing the mind... In being themselves, [sounds] open the minds of people who made them or listened to them to other possibilities that they had previously considered.[27]

In 1951, Cage composed theConcerto for Prepared Piano and Chamber Orchestra,which can be seen as an representation of the concept of interpenetration.[25][28][further explanation needed]

Chance music[edit]

Cage also explored the concept ofchance music—a composition without melodic structure or regularnotation.[26]The aforementionedConcerto for Prepared Pianoemploys the concepts posited in theAncient ChinesetextI Ching.[29][further explanation needed]

Visit to the anechoic chamber[edit]

In 1951, Cage visited theanechoic chamberatHarvard University.Cage entered the chamber expecting to hear silence, but he later wrote: "I heard two sounds, one high and one low. When I described them to the engineer in charge, he informed me that the high one was mynervous systemin operation, the low one my blood incirculation".[30]Cage had gone to a place where he expected total silence, and yet heard sound. "Until I die there will be sounds. And they will continue following my death. One need not fear about the future of music".[31]The realization as he saw it of the impossibility of silence led to the composition of4′33″.

White Painting[edit]

Another cited influence for this piece came from the field of the visual arts.[13]Cage's friend and sometimes colleagueRobert Rauschenberghad produced, in 1951, a series of white paintings (collectively namedWhite Painting), seemingly "blank" canvases (though painted with white house paint) that in fact change according to varying light conditions in the rooms in which they were hung, the shadows of people in the room and so on. This inspired Cage to use a similar idea, as he later stated, "Actually what pushed me into it was not guts but the example of Robert Rauschenberg. His white paintings... when I saw those, I said, 'Oh yes, I must. Otherwise I'm lagging, otherwise music is lagging'."[32]In an introduction to an article "On Robert Rauschenberg, Artist, and His Works", John Cage writes: "To Whom It May Concern: The white paintings came first; my silent piece came later."[33]

The composition[edit]

Premiere and initial reception[edit]

They missed the point. There's no such thing as silence. What they thought was silence, because they didn't know how to listen, was full of accidental sounds. You could hear the wind stirring outside during the first movement. During the second, raindrops began pattering the roof, and during the third the people themselves made all kinds of interesting sounds as they talked or walked out.

The premiere of the three-movement4′33″was given byDavid Tudoron August 29, 1952, inMaverick Concert Hall,Woodstock, New York,as part of a recital of contemporary piano music. The audience saw him sit at the piano and, to mark the beginning of the piece, close the keyboard lid. Some time later he opened it briefly, to mark the end of the first movement. This process was repeated for the second and third movements.[f]Although the audience was enthusiastic about contemporary art, the premiere was met with widespread controversy and scandal,[34]such that Calvin Tomkins notes: "The Woodstock audience considered the piece either a joke or an affront, and this has been the general reaction of most people who have heard it, or heard of it, ever since. Some listeners have been unaware they were hearing it at all".[35]

General reception[edit]

Music criticKyle Ganncalled the piece "one of the most misunderstood pieces of music ever written and yet, at times, one of the avant-garde’s best understood as well". He dismissed the idea that 4′33″ was a joke or a hoax, wrote that the theory of Dada and theater have some justification, and said that for him the composition is a "thought experiment". He concluded that the idea that 4′33″ is a "Zen practice" "may be the most directly fertile suggestion".[36]

Analysis[edit]

The composition is an indispensable contribution to the Modernist movement[37][38]and formalized noise music as a genre.[39][40]Noise music is seen as the anathema to the traditional view of harmony in music, exploiting random sound patterns 'noise' in the process of making music—the "detritus of the music process".[41]Paul Hegartynotes that: "The silence of the pianist in4'33 "can be understood as the traditional silence of the audience so that it can appreciate the music being played. Music itself is sacrificed, sacrificed to the musicality of the world ".[42]For Hegarty,4′33″,is made up of incidental sounds that represent perfectly the tension between "desirable" sound (properly played musical notes) and undesirable "noise" that make up all noise music.[42]It is made of three movements.[37][38][further explanation needed]

Intentions[edit]

4′33″challenges, or rather exploits to a radical extent, the social regiments of the modern concert life etiquette, experimenting on unsuspecting concert-goers to prove an important point. First, the choice of a prestigious venue and the social status of the composer and the performers automatically heightens audience's expectations for the piece. As a result, the listener is more focused, giving Cage's4′33″the same amount of attention (or perhaps even more) as if it wereBeethoven's Ninth Symphony.[43]Thus, even before the performance, the reception of the work is already predetermined by the social setup of the concert. Furthermore, the audience's behavior is limited by the rules and regulation of the concert hall; they will quietly sit and listen to 4′33″ of ambient noise. It is not easy to get a large group of people to listen to ambient noise for nearly five minutes, unless they are regulated by the concert hall etiquette.

The second point made by4′33″concerns duration. According to Cage, duration is the essential building block of all of music. This distinction is motivated by the fact that duration is the only element shared by both silence and sound. As a result, the underlying structure of any musical piece consists of an organized sequence of "time buckets".[44]They could be filled with either sounds, silence or noise; where neither of these elements is absolutely necessary for completeness. In the spirit of his teacherSchoenberg,Cage managed to emancipate the silence and the noise to make it an acceptable or, perhaps, even an integral part of his music composition.4′33″serves as a radical and extreme illustration of this concept, asking that if the time buckets are the only necessary parts of the musical composition, then what stops the composer from filling them with no intentional sounds?[45]

The third point is that the work of music is defined not only by its content but also by the behavior it elicits from the audience.[43]In the case ofIgor Stravinsky'sRite of Spring,this would consist of widespread dissatisfaction leading up to violent riots.[46]In Cage's4′33″,the audience felt cheated by having to listen to no composed sounds from the performer. Nevertheless, in4′33″the audience contributed the bulk of the musical material of the piece. Since the piece consists of exclusively ambient noise, the audience's behavior, their whispers and movements, are essential elements that fill the above-mentioned time buckets.[47]

Above all,4'33 "—in fact, more of an experiment than a composition—is intended to question the very notion of music. Cage believed that "silence is a real note" and "will henceforth designate all the sounds not wanted by the composer".[48]He had the ambition to go beyond what is achievable on a piece of paper by leaving the musical process to chance, inviting the audience to closely monitor the ambient noises characterizing the piece.[48]French musicologistDaniel Charlesproposes a related theory;4′33″is—resulting from the composer's lack of interference in the piece—a 'happening', since, during the performance, the musician is more of an actor than a 'musician', per se.[49][50]He also notes that it resembles aDuchamp-stylefound object,due to the fact that it creates art from objects that do not serve an artistic function, as silence is often associated with the opposite of music.[50][51]In fact, Cage's composition draws parallels to theDadaistmovement due to the involvement of 'anti-art' objects into art (music), its apparent nonsensical nature, and blatant defiance of the status quo.[52][53]

Silence[edit]

Indeed, the perceived silence characterizing Cage's composition is not actually 'silence', but the interference of the ambient sounds made by the audience and environment.[8]To him, any auditory experience containing some degree of sound, and hence can be considered music,[54]countering its frequent label as "four minutes thirty-three seconds of silence".[55][56]

Psychological impact[edit]

TheLacanianapproach implies a profound psychological connection to4'33 ",as the individual is invited to ponder their surroundings and psyche.[57]In a 2013TED talk,psychologist Paul Bloomput forward4′33″as one example to show that knowing about the origin of something influences how one formulates an opinion on it. In this case, one can deem the five minutes of silence in Cage's composition as different than five minutes of ordinary silence, as in a library, as they know where this silence originates; hence, they can feel motivated to pay to listen to4'33 ",even though it is inherently no different than five minutes of ordinary silence.[58][59]

Surrealist automatism[edit]

Some musicologists have argued that4′33″is an example ofsurrealist automatism.Since theRomantic Eracomposers have been striving to produce music that could be separated from any social connections, transcending the boundaries of time and space. In automatism, composers and artists strive to eliminate their role in the creation of work, motivated by the belief that self-expression always includes the infiltration of the social standards—that the individual (including the musician) is subjected to from birth—in artistic truth (the message the musician wishes to convey).[45][60]

Therefore, the only method by which the listener can realize artistic truth involves the separation of the musician from their work. In4'33 ",the composer has no impact in his work, as Cage cannot control the ambient sounds detected by the audience. Hence, the composition is automatic since the musician has no involvement in how the listener interprets it.[45]

Indeterminacy[edit]

This sectionneeds expansion.You can help byadding to it.(February 2024) |

A pioneer ofmusical indeterminacy,Cage defined it as "the ability of a piece to be performed in substantially different ways".[61]

Versions[edit]

Of the score[edit]

Several versions of the score exist;[34]the four below are the main samples that could be identified. Their shared quality is the composition's duration of four minutes and thirty-three seconds—reflected in the title '4'33 "'—[62]but there is some discrepancy between the lengths of individual movements, specified in different versions of the score.[g][h]The causes of this discrepancy are not currently understood.[34]

Woodstock manuscript and reproduction[edit]

The original Woodstock manuscript (August 1952) is written in conventionalnotationand dedicated to David Tudor – the first to perform the piece. It is currently lost, but Tudor did attempt to recreate the original score, reproduced in William Fetterman's bookJohn Cage's Theatre Pieces: Notations and Performances.[66]The reproduction notes that4'33 "can be performed for any instrument or combination of instruments. Regarding tempo, it includes atreble clefstaffwith a 4/4time signature,and the beginning of each sentence is identified withRoman numeralsand ascaleindication: '60 [quarter] = 1/2-inch'. At the end of each sentence, there is information about each movement's duration in minutes and seconds; these are: 'I = 30 seconds', 'II = 2 minutes 23 seconds' and 'III = 1 minute 40 seconds'.[67]Tudor commented: "It's important that you read the score as you're performing it, so there are these pages you use. So you wait, and then turn the page. I know it sounds very straight, but in the end it makes a difference".[68]

Kremen manuscript[edit]

The Kremen manuscript (1953) is written in graphic, space-time notation—which Cage dubbed "proportional notation" —and dedicated to the American artistIrwin Kremen.The movements of the piece are rendered as space between long vertical lines; atempoindication is provided (60), and at the end of each movement the time is indicated in minutes and seconds. In page 4, the note '1 PAGE = 7 INCHES = 56″' is included. The same instructions, timing and indications to the reproduced Woodstock manuscript are implemented.[69][70]

First Tacet Edition[edit]

The so-calledFirst Tacet Edition(orTyped Tacet Edition) (1960) is a typewritten score, originally printed inEdition Petersas EP No. 6777.[62]It lists the three movements using Roman numbers, with the word 'tacet' underneath each. A note by Cage describes the first performance and mentions that "the work may be performed by any instrumentalist or combination of instrumentalists and last any length of time". In doing so, Cage not only regulates the reading of the score, but also determines the identity of the composition.[71][72]Conversely to the initial two manuscripts, Cage notes that the premiere organized the movements into the following durations: 33 ", 2'40" and 1'20 ", and adds that the their length" must be found by chance "performance.[73][71]TheFirst Tacet Editionis described inMichael Nyman's bookExperimental Music: Cage and Beyond,but is not reproduced.[74]

Second Tacet Edition[edit]

The so-calledSecond Tacet Edition(orCalligraphic Tacet Edition) (1986) is the same as the First, except that it is printed in Cage's calligraphy, and the explanatory note mentions the Kremen manuscript.[75]It is also classified as EP No. 6777 (i.e., it carries the same catalog number as the firstTacet Edition).[62]Additionally, a facsimile, reduced in size, of the Kremen manuscript, appeared in July 1967 inSource1, no. 2:46–54.

Of the composition itself[edit]

4′33″ No. 2[edit]

In 1962, Cage wrote0′00″,which is also referred to as4′33″ No. 2.The directions originally consisted of one sentence: "In a situation provided with maximum amplification, perform a disciplined action".[76]At the first performance Cage had to write that sentence. The second performance added four new qualifications to the directions: "the performer should allow any interruptions of the action, the action should fulfill an obligation to others, the same action should not be used in more than one performance, and should not be the performance of a musical composition".[77]

One3[edit]

In late 1989, three years before his death, Cage revisited the idea of4′33″one last time. He composedOne3,the full title of which isOne3= 4′33″ (0′00″) + [G Clef].As in all of theNumber Pieces,'One' refers to the number of performers required. The score instructs the performer to build asound systemin the concert hall, so that "the whole hall is on the edge offeedback,without actually feeding back ". The content of the piece is the electronically amplified sound of the hall and the audience.[78]

Legacy[edit]

This sectionneeds expansion.You can help byadding to it.(February 2024) |

Controversies[edit]

This sectionneeds expansion.You can help byadding to it.(February 2024) |

Plagiarism[edit]

In July 2002, Cage's heirs sued British singer-songwriterMike Battfor plagiarism for the 'song' "A One Minute Silence": literally, a minute of silence. To support his crossover ensembleThe Planets,he inserted a one-minute pause in their February 2002 album "Classical Graffiti" under the authorship 'Batt/Cage'—[79]supposedly to honor the composer. He was then sued by the Mechanical Copyright Protection Society for "plagiarizing Cage's silence [4'33 "].[79]

Initially, Batt said he would defend himself against these accusations, stating that "A One Minute Silence" was "a much better silent piece" and that he was "able to say in one minute what Cage could only say in four minutes and 33 seconds".[80]He eventually reached an out-of-court settlement with the composer's heirs in September 2002 and paid an undisclosed six-figure compensation.[60][81]However, in December 2010, Batt admitted that the alleged legal dispute was a publicity stunt and that he had actually only made a donation of £1,000 to theJohn Cage Foundation.[81]

Christmas number one campaign[edit]

In the week leading up to Christmas 2010, aFacebook pagewas created to encourage residents of the United Kingdom to buy a new rendition of4′33″,[82]in the hope that it would prevent the winner of theseventh series ofThe X Factor,Matt Cradle,from topping theUK Singles Chartand becoming theChristmas number one.[83]The page was inspired by a similar campaign the year prior, in which a Facebook page set up by English radio DJJon Morterand his then-wife Tracey, prompting people to buyRage Against the Machine's "Killing in the Name"in the week before Christmas 2009 to make it the Christmas number one.[84]Hence, the4'33 "campaign was dubbed 'Cage Against the Machine'.[85][86]The creators of the Facebook page hoped that reaching number one would promote Cage's composition and "make December 25 'a silent night'."[87]

The campaign received support from several celebrities. It first came into prominence afterscience writerBen Goldacrementioned it on his Twitter profile.[88]Despite many similar campaigns occurring that year,The Guardianjournalist Tom Ewing considered 'Cage Against the Machine' "theonlyeffort this year with a hope of [reaching number one] ".[89]XFMDJEddy Temple-MorrisandThe Guardianjournalist Luke Bainbridge also voiced their support.[90][91]Ultimately, the rendition of4'33 "failed to reach number one, only peaking at number 21 on the charts; the winning song ofX Factorinstead became Christmas number one of 2010.[92][93]

Notable performances and recordings[edit]

Due to its unique avant-garde style, many musicians and groups have performed4'33 ",featuring in several works such as albums.

- Frank Zapparecorded a version of the composition as part of the collaborative albumA Chance Operation: The John Cage Tribute,released byKoch Entertainmentin 1993.[94]

- Several performances of4′33″including a 'techno remix' of theNew Waverproject were broadcast on Australian radio stationABC Classic FM,as part of a program exploring "sonic responses" to Cage's work.[95]Another of these 'responses' was the rendition named 'You Can Make Your Own Music', recorded by the Swedish electronic bandCovenantas part of their 2000 albumUnited States of Mind.[96]

- On January 16, 2004, at theBarbican Centrein London, theBBC Symphony Orchestragave the United Kingdom's first orchestral performance of this work, conducted byLawrence Foster.The performance was broadcast live onBBC Radio 3,and the station faced a unique problem; its emergency system—automatically switching on and playing separate music in a period of perceived silence 'dead air'—interrupted the broadcast, and had to be switched off.[97]On the same day, atongue-in-cheekversion was recorded by the staff ofThe Guardian.[98]

- On December 5, 2010, an international simultaneous performance of4′33″took place among 200 performers, amateur and professional musicians, and artists. The global orchestra, conducted live by Bob Dickinson, via video link, performed the piece in support of the 'Cage Against The Machine' campaign to bring4′33″to 2010 Christmas Number 1 in theUK Singles Chart.[99]

- On November 17, 2015, the television programThe Late Show with Stephen Colbertuploaded a video of the piece being performed by a cat, showing that its musician is not required to be human.[100]

- In May 2019,Mute Recordsreleased a compilation box set entitledSTUMM433featuring interpretations of4′33″by more than 50 artists which had collaborated with the record label, includingLaibach,Depeche Mode,Cabaret Voltaire,Einstürzende Neubauten,Goldfrapp,Moby,Erasure.[101]

- On October 31, 2020, theBerlin Philharmonicclosed their last concert before a government-mandatedCOVID-19 related lockdownwith a performance of the piece, conducted byKirill Petrenko,"to draw attention to the plight of artists following the lockdown of cultural institutions".[102]

Notes and references[edit]

Explanatory notes[edit]

- ^Often pronounced simply as 'four thirty-three', but sometimes alternatively as 'four minutes, thirty-three seconds' or 'four minutes and thirty-three seconds'.[1]

- ^The labelling of4'33 "as a 'composition' is controversial, as it isintrinsicallysilence—the very opposite of music, which is often defined as "sounds organized by humans", at the very least.[2]However, Cage maintains that his piece is not silence, but the combination of ambient noises heard by the audience, which can be deemed 'music'.[3]Therefore, for the sake of consistency,4'33 "can be considered a 'composition'.

- ^Cage divided the composition into three distinct movements,[1]but this is often disregarded; the piece is silence, and a movement is defined as "sections of a work [which] may be distinguished in terms of style, key and tempo".[4]While there is no perceived distinguishment between the three sections, Cage insists that there is, as the variation in ambient sounds between each movement is, in itself, a distinction.[5]

- ^According to a reproduction of the original Woodstock manuscript.[6]

- ^This article distinguishes between 'silence' and 'absolute silence'. 'Silence' is defined as the lack of soundswithinthe composition itself, while 'absolute silence' is the complete lack of sounds, both within and outside the composition—so, silence in the hall in which4'33 "is performed. Cage insists that no absolute silence can exist; the perceived silence of his composition is, in fact, not absolute, since many ambient sounds can be heard while it is performed.[7]

- ^The actions of Tudor in the first performance are often misdescribed so that the lid is explained as being open during the movements. Cage's handwritten score (produced after the first performance) states that the lid was closed during the movements, and opened to mark the spaces between.

- ^The Woodstock printed program specifies the lengths 30″, 2′23″ and 1′40″, as does the Kremen manuscript, but the latter versions have a distinguished tempo. In the First Tacet Edition, Cage writes that at the premiere the timings were 33″, 2′40″ and 1′20″, and in the Second Tacet Edition, he adds that after the premiere, a copy had been made for Irwin Kremen, in which the lengths of the movements were 30″, 2′23″ and 1′40″.[63]Some later performances would not abide by this duration, as seen in Frank Zappa's 1993 recording on the 1993 double-CDA Chance Operation: The John Cage Tribute,amounting to five minutes and fifty-three seconds.[64]

- ^While Cage specifies three movements incorporated in the piece,[65]some later performances included a different number of movements. An example is the recording by the Hungarian Amadinda Percussion Group, consisting of a recording of ambient outdoor bird song in one movement;[64]Frank Zappa's recording also includes wildly different time bands: '35 ", 1'05", 2'21 ", 1'02", and 50 "', but the number ofmovementscannot be identified.[64]

Citations[edit]

- ^abSolomon 2002.

- ^Arnold & Kramer 2023,p. 5.

- ^abKostelanetz 2003,p. 70.

- ^Thomsett 2012,p. 135.

- ^Kostelanetz 2003,p. 69–70.

- ^Bormann 2005,p. 194.

- ^Fetterman 1996,p. 71.

- ^abKostelanetz 2003,pp. 69–70

- ^Eisinger, Dale (April 9, 2013)."The 25 Best Performance Art Pieces of All Time".Complex.RetrievedFebruary 28,2021.

- ^Pritchett, Kuhn & Garrett 2012

- ^Pritchett 1993,pp. 59, 138

- ^Revill 1993,p. 162

- ^abRevill 1993,p. 164

- ^Stein, Judith(January 1, 2009)."Interview: Alfred Leslie".Art in America.p. 92. Archived fromthe originalon December 4, 2010.RetrievedOctober 8,2010.

- ^Busoni 1916

- ^Allais 1897,pp. 23–26

- ^abLiu 2017,p. 54

- ^Dickinson 1991,p. 406

- ^Bek 2001

- ^Carpenter 2009,p. 60

- ^"JOHN CAGE; Similar Silence".The New York Times.September 13, 1992.RetrievedFebruary 11,2024.

- ^"New Jazz: 'All or Nothing at All'".The Washington Post.March 16, 1947. pp. S7.

- ^Pritchett 1993,p. 74

- ^Pritchett 1993,pp. 74–75

- ^abPritchett 1993,p. 75

- ^abBurgan 2003,p. 52

- ^Kostelanetz 2003,p. 42

- ^Nicholls 2002,p. 220

- ^Nicholls 2002,pp. 201–202

- ^"A few notes about silence and John Cage".CBC.November 24, 2004. Archived fromthe originalon February 12, 2006.

- ^Cage 1961,p. 8.

- ^Kostelanetz 2003,p. 71.

- ^Cage 1961.

- ^abcSolomon 2002

- ^Bormann 2005,p. 200

- ^Gann, Kyle (April 1, 2010)."From No Such Thing as Silence: John Cage's 4'33" - New Music USA ".newmusicusa.org.RetrievedApril 3,2024.

- ^abPritchett, Kuhn & Garrett 2012

- ^abKostelanetz 2003,pp. 69–71, 86, 105, 198, 218, 231

- ^Hegarty 2007,pp. 11–12

- ^Priest 2008,p. 59

- ^Priest 2008,pp. 57–58

- ^abHegarty 2007,p. 17

- ^abTaruskin 2009,p. 71

- ^Taruskin 2009,p. 56.

- ^abcFiero 1995,pp. 97–99

- ^"This is what REALLY happened at The Rite of Spring riot in 1913".Classic FM.October 15, 2018.RetrievedFebruary 9,2024.

- ^Harding 2013,pp. 78–79

- ^abCharles 1978,p. 261

- ^Charles 1978,p. 69

- ^abCharles 1978,p. 262

- ^Gann 2010,p. 17

- ^Gann 2010,pp. 16–17, 74

- ^Skinner, Gillis & Lifson 2012,p. 4

- ^Gutmann, Peter(1999)."John Cage and the Avant-Garde: The Sounds of Silence".Classical Notes.RetrievedApril 4,2007.

- ^Fetterman 1996,p. 69.

- ^Lienhard 2003,p. 254.

- ^Pluth & Zeiher 2019,pp. 75–78

- ^Pluth & Zeiher 2019,pp. 75–76

- ^Paul Bloom(July 27, 2011)."The origins of pleasure".ted.

- ^abHarris 2005,pp. 66–67

- ^Pritchett 1993,p. 108

- ^abcPublished score,Edition Peters6777.

- ^Fetterman 1996,p. 69–80.

- ^abcFetterman 1996,p. 83.

- ^Fetterman 1996,p. 80.

- ^Fetterman 1996,p. 74

- ^Bormann 2005,p. 194

- ^Fetterman 1996,p. 75

- ^Fetterman 1996,pp. 76–78

- ^Bormann 2005,p. 210

- ^abBormann 2005,pp. 222–223

- ^Fetterman 1996,p. 79

- ^Fetterman 1996,p. 80

- ^Nyman 1974,p. 3

- ^Bormann 2005,pp. 225–227

- ^Craenen 2014,p. 58

- ^Fetterman 1996,pp. 84–89

- ^Fetterman 1996,pp. 94–95

- ^abMcCormick, Neil (December 9, 2010)."Revealed: what really happened when a Womble took on John Cage".The Telegraph.Archivedfrom the original on December 10, 2010.RetrievedFebruary 14,2024.

- ^"Composer pays for piece of silence".CNN.September 23, 2002.RetrievedFebruary 12,2024.

- ^ab"Wombles composer Mike Batt's silence legal row 'a scam'".BBC.December 9, 2010.RetrievedFebruary 12,2024.

- ^"John Cage's4′33 "for Christmas Number One 2010 ".Facebook. December 2009.RetrievedMarch 1,2021.

- ^Gilbert, Ben (October 4, 2010)."Cowell's second festive humiliation?".Yahoo! Music.Archived fromthe originalon October 18, 2010.RetrievedOctober 28,2010.

- ^"Sound of silence vies to be Christmas number one".The Daily Telegraph.London. October 16, 2010.Archivedfrom the original on October 19, 2010.RetrievedOctober 28,2010.

- ^"Silence bids for Christmas number one".The Irish Times.October 15, 2010.Archivedfrom the original on October 27, 2010.RetrievedOctober 28,2010.

- ^Eaton, Andrew (October 5, 2010)."At time of writing, Cage Against The Machine has almost 16,000 followers on Facebook"(JP).Scotland on Sunday.RetrievedOctober 28,2010.

- ^"Campaigners launch bid to make silent track Christmas No1 ahead of X Factor winner".Daily Record.October 15, 2010.RetrievedNovember 7,2019.

- ^Goldacre, Ben(July 19, 2010)."John Cage's4′33 "for Xmas... "Twitter.RetrievedOctober 28,2010.

- ^Ewing, Tom (September 30, 2010)."John Cage's4′33 ":the festive sound of a defeated Simon Cowell ".The Guardian.London.Archivedfrom the original on October 7, 2010.RetrievedOctober 28,2010.

- ^Temple-Morris, Eddy(October 27, 2010)."Once more unto the breach dear friends".Archived fromthe originalon November 12, 2010.RetrievedOctober 28,2010.

- ^Luke Bainbridge (December 13, 2010)."Why I'm backing Cage Against the Machine for Christmas No 1".The Guardian.London.Archivedfrom the original on January 10, 2011.RetrievedDecember 13,2010.

- ^"Top 40 UK Official Singles Chart".Official Charts.December 25, 2010.RetrievedDecember 19,2010.

- ^Symonds & Karantonis 2013,p. 227

- ^"Various – A Chance Operation – The John Cage Tribute".Discogs.RetrievedFebruary 10,2024.

- ^Kouvaras 2013

- ^Reed 2013,p. 43

- ^"BBC orchestra silenced at the Barbican and on Radio 3; John Cage Uncaged: A weekend of musical mayhem".BBC.January 12, 2004.RetrievedFebruary 12,2024.

- ^"The sound of silence".The Guardian.January 16, 2004.RetrievedFebruary 12,2004.

- ^Lebrecht, Norman (December 11, 2010)."We're pitching the silence of John Cage against the noise of Simon Cowell".The Daily Telegraph.RetrievedDecember 17,2010.

- ^NOLA The Cat Performs John Cage's 4'33 "(YouTube). The Late Show with Stephen Colbert. November 17, 2015.

- ^"STUMM433".Mute Records.RetrievedFebruary 12,2024.

- ^"Video: Kirill Petrenko conducts4'33 "by John Cage ".Berliner Philharmoniker.November 2, 2020. Archived fromthe originalon November 2, 2020.RetrievedFebruary 10,2021.

Bibliography[edit]

- Allais, Alphonse (1897),Album primo–avrilesque,Paris, France: P. Ollendorff

- Arnold, Allison E.; Kramer, Jonathan C. (2023).What in the World is Music?(2nd ed.). United States:Routledge.ISBN9781032341491.

- Bek, Joseph (2001). "Erwin Schulhoff". InSadie, Stanley;Tyrrell, John(eds.).The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians(2nd ed.). London:Macmillan Publishers.ISBN978-1-56159-239-5.

- Bernstein, David W.; Hatch, Christopher (2001).Writings through John Cage's Music, Poetry, and Art.Chicago, Illinois:University of Chicago Press.ISBN0-226-04408-4.

- Bormann, Hans-Friedrich (2005).Verschwiegene Stille: John Cages performative Ästhetik[Secretive Silence: John Cage's Performative Aesthetics] (in German).Paderborn,Germany: Fink Wilhelm GmbH + Co.KG.ISBN978-3-7705-4147-8.

- Burgan, Michael (2003).Buddhist Faith in America.New York City:Facts on File, Inc.ISBN0-8160-4988-2.

- Busoni, Ferruccio (1916).Entwurf einer neuen Ästhetik der Tonkunst[Sketch of a New Aesthetic of Music] (in German).Leipzig,Germany: Insel-Verlag.

- Cage, John (1961).Silence: Lectures and Writings.Middletown, Connecticut:Wesleyan University Press.

- Carpenter, Humphrey (2009).The Brideshead Generation: Evelyn Waugh and His Friends.United States:Faber and Faber.ISBN978-0571248339.

- Craenen, Paul (2014).Composing under the Skin: The Music-making Body at the Composer's Desk.Leuven, Belgium:Leuven University Press.ISBN978-9058679741.

- Charles, Daniel (1978).Gloses sur John Cage(in French). Paris, France: Union générale d'éditions.ISBN2264008555.

- Dickinson, Peter (1991). "Reviews of Three Books on Satie".The Musical Quarterly.75(3): 404–409.doi:10.1093/mq/75.3.404.

- Fetterman, William (1996).John Cage's Theatre Pieces: Notations and Performances.Amsterdam, the Netherlands:Harwood Academic Publishers.ISBN3-7186-5642-6.

- Fiero, Gloria Konig (1995).The Humanistic Tradition, Book 6: The Global Village of the Twentieth Century(2nd ed.). Brown & Benchmark Pub.ISBN0-6972-4222-6.

- Gann, Kyle (2010).No Such Thing as Silence: John Cage's 4′33.New Haven, Connecticut:Yale University Press.ISBN978-0-300-13699-9.

- Harding, James Martin (2013).The Ghosts of the Avant-Garde(s): Exercising Experimental Theater and Performance.Ann Arbor, Michigan:University of Michigan Press.ISBN978-0-4720-3610-3.

- Harris, Jonathan (2005).Art, Money, Parties: New Institutions in the Political Economy of Contemporary Art.Liverpool, United Kingdom:Liverpool University Press.ISBN978-0853237198.

- Hegarty, Paul (2007).Noise/Music: A History.New York City: Continuum International Publishing Group.ISBN978-0826417275.

- Skinner, David; Gillis, Anna Maria; Lifson, Amy (November–December 2012)."Humanities Volume 33, Issue 6".Humanities.Washington D.C., United States:National Endowment for the Humanities.

- Kostelanetz, Richard(2003).Conversing with John Cage.New York City: Routledge.ISBN0-415-93792-2.

- Kouvaras, Linda Ioanna (2013).Loading the Silence: Australian Sound Art in the Post-Digital Age.Melbourne:Ashgate Publishing.ISBN9781315592831.

- Lienhard, John H.(2003).Inventing Modern: Growing Up with X-Rays, Skyscrapers, and Tailfins.New York City:Oxford University Press.ISBN0-19-516032-0.

- Liu, Gerard C. (2017).Music and the Generosity of God.Princeton, New Jersey:Palgrave Macmillan.ISBN978-3-319-69492-4.

- Nicholls, David (2002).The Cambridge Companion to John Cage.Cambridge, United Kingdom:Cambridge University Press.ISBN978-0521789684.

- Nyman, Michael (1974).Experimental Music: Cage and Beyond.London, England:Studio Vista.ISBN0-289-70182-1.

- Pluth, Ed; Zeiher, Cindy (2019).On Silence: Holding the Voice Hostage.Palgrave Pivot.ISBN978-3030281465.

- Priest, Gail (2008).Experimental Music: Audio Explorations in Australia.Sydney:University of New South Wales Press.ISBN978-1921410079.

- Pritchett, James (1993).The Music of John Cage.Cambridge, United Kingdomand New York City:Cambridge University Press.ISBN0-521-56544-8.

- Pritchett, James; Kuhn, Laura & Garrett, Charles Hiroshi (2012). "John Cage".Grove Music Online(8th ed.).Oxford University Press.doi:10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.A2223954.ISBN978-1-56159-263-0.

- Reed, S. Alexander (2013).Assimilate: A Critical History of Industrial Music.New York City: Oxford University Press.ISBN9780199832606.

- Revill, David (1993).The Roaring Silence: John Cage – A Life.New York City:Arcade Publishing.ISBN978-1-55970-220-1.

- Solomon, Larry J. (2002) [1998].The Sounds of Silence: John Cage and 4′33(revised ed.). Archived fromthe originalon January 9, 2018.

- Symonds, Dominica; Karantonis, Pamela (2013).The Legacy of Opera: Reading Music Theatre as Experience and Performance.The Netherlands:Brill Academic Pub.ISBN978-9042036918.

- Taruskin, Richard(2009).Oxford History of Western Music: Volume 5.New York City: Oxford University Press.ISBN978-0-19-538630-1.

- Thomsett, Michael C. (2012).Musical Terms, Symbols and Theory: An Illustrated Dictionary.Jefferson, North Carolina:McFarland & Company, Inc.ISBN978-0-7864-6757-0.

Further reading[edit]

- Arns, Inke and Daniels, Dieter. 2012.Sounds Like Silence.Hartware MedienKunstVerein. Leipzig: Spector Books.ISBN978-3-940064-41-7

- Davies, Stephen. 1997. "John Cage's4′33″:Is it music? "Australasian Journal of Philosophy,vol. 75, no. 4, pp. 448–462.doi:10.1080/00048402.2017.1408664

- Dodd, Julian. 2017. "What4′33″Is ".Australasian Journal of Philosophy.doi:10.1080/00048409712348031

- Garten, Joel. February 20, 2014.Interview With MoMA Curator David Platzker About the New Exhibition on John Cage.The Huffington Post.

- Katschthaler, Karl. 2016. "Absence, Presence and Potentiality: John Cage's4′33″Revisited ", pp. 166–179.doi:10.1163/9789004314863_011,inWolf, Wernerand Bernhart, Walter (eds.).Silence and Absence in Literature and Music.Leiden: Brill.ISBN978-90-04-31485-6

- Lipov, Anatoly. 2015. "4'33" as the Play of Silent Presence. Stillness, or Anarchy of Silence? "Culture and Art,numbers 4, pp. 436–454,doi:10.7256/2222-1956.2015.4.15062and 6, pp. 669–686,doi:10.7256/2222-1956.2015.6.16411.

See also[edit]

- Monotone-Silence Symphony,a composition by Yves Klein featuring both sound and extended silence

External links[edit]

- What John Cage's silent symphony really means",BBC News

- "Radio 3 plays 'silent symphony'",BBC Online. (includesRealAudiosound file)

- A quiet night out with Cagefrom the UKObserver

- The Music of Chancefrom the UKGuardiannewspaper

- The Sounds of Silencefurther commentary by Peter Gutmann

- Videoof a 2004 orchestral performance

Audio

- John Cage's4′33″inMIDI,OGG,Au,andWAVformats.

- John Cage's4′33″fromNational Public Radio's "The 100 most important American musical works of the 20th century" (RealAudiofile format)

- Interview with Kyle Gann about 4'33 "on The Next Track podcast

App

- John Cage's4′33″as aniPhoneapp, published by the John Cage Trust (2014)