Afrikaans

| Afrikaans | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | [afriˈkɑːns] |

| Native to | |

| Region | Southern Africa |

| Ethnicity | Afrikaners Basters Cape Coloureds Cape Malays Griqua Oorlams |

Native speakers | 7.2 million (2016) 10.3 million L2 speakers in South Africa (2011)[1] |

Early forms | |

| Dialects | |

| Latin script (Afrikaans Alpha bet),Arabic script | |

| Signed Afrikaans[2] | |

| Official status | |

Official language in | |

Recognised minority language in | |

| Regulated by | Die Taalkommissie |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 | af |

| ISO 639-2 | afr |

| ISO 639-3 | afr |

| Glottolog | afri1274 |

| Linguasphere | 52-ACB-ba |

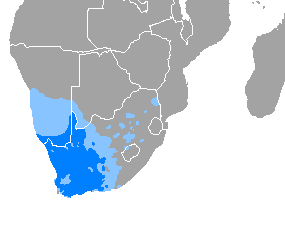

spoken by a majority spoken by a minority | |

Afrikaans(/ˌæfrɪˈkɑːns/AF-rih-KAHNSS,/ˌɑːf-,-ˈkɑːnz/AHF-, -KAHNZ)[3][4]is aWest Germanic language,spoken inSouth Africa,Namibiaand (to a lesser extent)Botswana,ZambiaandZimbabwe.It evolved from theDutch vernacular[5][6]ofSouth Holland(Hollandic dialect)[7][8]spoken by thepredominantly Dutch settlersandenslaved populationof theDutch Cape Colony,where it gradually began to develop distinguishing characteristics in the course of theseventeenthandeighteenthcenturies.[9]

Although Afrikaans has adopted words from other languages, includingGermanand theKhoisan languages,an estimated 90 to 95% of the vocabulary of Afrikaans is of Dutch origin.[n 1]Differences between Afrikaans and Dutchoften lie in the moreanalyticmorphologyand grammar of Afrikaans, and different spellings.[n 2]There is a large degree ofmutual intelligibilitybetween the two languages, especially inwritten form.[10]

Etymology[edit]

The name of the language comes directly from the Dutch wordAfrikaansch(now spelledAfrikaans)[11]meaning "African".[12]It was previously referred to as "Cape Dutch" (Kaap-Hollands/Kaap-Nederlands),a term also used to refer to theearly Cape settlerscollectively, or the derogatory "kitchen Dutch" (kombuistaal) from its use by slaves of colonial settlers "in the kitchen".

History[edit]

Origin[edit]

The Afrikaans language arose in theDutch Cape Colony,through a gradual divergence from EuropeanDutch dialects,during the course of the 18th century.[13][14]As early as the mid-18th century and as recently as the mid-20th century, Afrikaans was known in standard Dutch as a "kitchen language" (Afrikaans:kombuistaal), lacking the prestige accorded, for example, even by the educational system in Africa, to languages spoken outside Africa. Other early epithets setting apartKaaps Hollands( "Cape Dutch",i.e. Afrikaans) as putatively beneath official Dutch standards includedgeradbraakt,gebrokenandonbeschaafd Hollands( "mutilated/broken/uncivilised Dutch" ), as well asverkeerd Nederlands( "incorrect Dutch" ).[15][16]

| 'Hottentot Dutch' | |

|---|---|

Dutch-basedpidgin | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | None(mis) |

| Glottolog | hott1234 |

Den Besten theorises that modern Standard Afrikaans derives from two sources:[17]

- Cape Dutch,a direct transplantation of European Dutch to Southern Africa, and

- 'Hottentot Dutch',[18]apidginthat descended from 'Foreigner Talk' and ultimately from the Dutch pidgin spoken by slaves, via a hypotheticalDutch creole.

Thus, in his view, Afrikaans is neither a creole nor a direct descendant of Dutch, but a fusion of two transmission pathways.

Development[edit]

Most of the firstsettlerswhose descendants today are theAfrikanerswere from theUnited Provinces(nowNetherlands),[19]with up to one-sixth of the community of FrenchHuguenotorigin, and a seventh fromGermany.[20]

African and Asian workers,Cape Colouredchildren of European settlers andKhoikhoiwomen,[21]and slaves contributed to the development of Afrikaans. The slave population was made up of people fromEast Africa,West Africa,India,Madagascar,and theDutch East Indies(modernIndonesia).[22]A number were also indigenousKhoisanpeople, who were valued as interpreters, domestic servants, and labourers. Many free and enslaved women married or cohabited with the male Dutch settlers. M. F. Valkhoff argued that 75% of children born to female slaves in the Dutch Cape Colony between 1652 and 1672 had a Dutch father.[23]Sarah Grey Thomason and Terrence Kaufman argue that Afrikaans' development as a separate language was "heavily conditioned by nonwhites who learned Dutch imperfectly as a second language."[24]

Beginning in about 1815, Afrikaans started to replaceMalayas the language of instruction inMuslim schoolsinSouth Africa,written with theArabic Alpha bet:seeArabic Afrikaans.Later, Afrikaans, now written with theLatin script,started to appear in newspapers and political and religious works in around 1850 (alongside the already established Dutch).[13]

In 1875, a group of Afrikaans-speakers from the Cape formed theGenootskap vir Regte Afrikaaners( "Society for Real Afrikaners" ),[13]and published a number of books in Afrikaans including grammars, dictionaries, religious materials and histories.

Until the early 20th century, Afrikaans was considered aDutch dialect,alongsideStandard Dutch,which it eventually replaced as an official language.[10]Before theBoer wars,"and indeed for some time afterwards, Afrikaans was regarded as inappropriate for educated discourse. Rather, Afrikaans was described derogatorily as 'a kitchen language' or 'a bastard jargon', suitable for communication mainly between the Boers and their servants."[25][better source needed]

Recognition[edit]

In 1925, Afrikaans was recognised by the South African government as a distinct language, rather than simply a vernacular of Dutch.[13]On 8 May 1925, twenty-three years after theSecond Boer Warended,[25]theOfficial Languages of the Union Actof 1925 was passed—mostly due to the efforts of theAfrikaans-language movement—at a joint sitting of theHouse of Assemblyand theSenate,in which the Afrikaans language was declared a variety of Dutch.[26]TheConstitution of 1961reversed the position of Afrikaans and Dutch, so that English and Afrikaans were the official languages, and Afrikaans was deemed to include Dutch. TheConstitution of 1983removed any mention of Dutch altogether.

TheAfrikaans Language Monumentis located on a hill overlookingPaarlin theWestern Cape Province.Officially opened on 10 October 1975,[27]it was erected on the 100th anniversary of the founding of theSociety of Real Afrikaners,[28]and the 50th anniversary of Afrikaans being declared an official language of South Africa in distinction to Dutch.

Standardisation[edit]

The earliest Afrikaans texts were somedoggerel versefrom 1795 and a dialogue transcribed by a Dutch traveller in 1825. Afrikaans used the Latin Alpha bet around this time, although theCape Muslimcommunity used the Arabic script. In 1861, L.H. Meurant published hisZamenspraak tusschen Klaas Waarzegger en Jan Twyfelaar( "Conversation between Nicholas Truthsayer and John Doubter" ), which is considered to be the first book published in Afrikaans.[29]

The first grammar book was published in 1876; a bilingual dictionary was later published in 1902. The main modern Afrikaans dictionary in use is theVerklarende Handwoordeboek van die Afrikaanse Taal(HAT). A new authoritative dictionary, calledWoordeboek van die Afrikaanse Taal(WAT), was under development as of 2018. The officialorthographyof Afrikaans is theAfrikaanse Woordelys en Spelreëls,compiled byDie Taalkommissie.[29]

The Afrikaans Bible[edit]

This sectionneeds additional citations forverification.(February 2024) |

The Afrikaners primarily were Protestants, of theDutch Reformed Churchof the 17th century. Their religious practices were later influenced in South Africa by British ministries during the 1800s.[30]A landmark in the development of the language was the translation of the wholeBibleinto Afrikaans. While significant advances had been made in thetextual criticismof the Bible, especially the GreekNew Testament,the 1933 translation followed theTextus Receptusand was closely akin to theStatenbijbel.Before this, most Cape Dutch-Afrikaans speakers had to rely on the DutchStatenbijbel.ThisStatenvertalinghad its origins with theSynod of Dordrechtof 1618 and was thus in anarchaicform of Dutch. This was hard for Dutch speakers to understand, and increasingly unintelligible for Afrikaans speakers.

C. P. Hoogehout,Arnoldus Pannevis,andStephanus Jacobus du Toitwere the firstAfrikaans Bibletranslators. Important landmarks in the translation of the Scriptures were in 1878 with C. P. Hoogehout's translation of theEvangelie volgens Markus(Gospel of Mark,lit. Gospel according to Mark); however, this translation was never published. The manuscript is to be found in the South African National Library, Cape Town.

The first official translation of the entire Bible into Afrikaans was in 1933 byJ. D. du Toit,E. E. van Rooyen, J. D. Kestell, H. C. M. Fourie, andBB Keet.[31][32]This monumental work established Afrikaans as'n suiwer en ordentlike taal,that is "a pure and proper language" for religious purposes, especially amongst the deeplyCalvinistAfrikaans religious community that previously had been sceptical of aBible translationthat varied from the Dutch version that they were used to.

In 1983, a fresh translation marked the 50th anniversary of the 1933 version. The final editing of this edition was done by E. P. Groenewald, A. H. van Zyl, P. A. Verhoef, J. L. Helberg and W. Kempen. This translation was influenced byEugene Nida's theory ofdynamic equivalencewhich focused on finding the nearest equivalent in the receptor language to the idea that the Greek, Hebrew or Aramaic wanted to convey.

A new translation,Die Bybel: 'n Direkte Vertalingwas released in November 2020. It is the first trulyecumenicaltranslation of the Bible in Afrikaans as translators from various churches, including theRoman CatholicandAnglicanChurches, were involved.[33]

Classification[edit]

Afrikaans descended from Dutch dialects in the 17th century. It belongs to aWest Germanicsub-group, theLow Franconian languages.[34]Other West Germanic languages related to Afrikaans areGerman,English,theFrisian languages,and the unstandardised languagesLow GermanandYiddish.

Geographic distribution[edit]

Statistics[edit]

| Country | Speakers | Percentage of speakers | Year | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 650 | 0.001% | 2019 | [35] | |

| 49,375 | 0.68% | 2021 | [36] | |

| 8,082 | 0.11% | 2011 | [citation needed] | |

| 23,410 | 0.32% | 2016 | [37] | |

| 11,247 | 0.16% | 2011 | [38] | |

| 58 | 0.001% | 2021 | [39] | |

| 2,228 | 0.03% | 2016 | [40] | |

| 36 | 0.003% | 2011 | [citation needed] | |

| 219,760 | 3.05% | 2011 | [citation needed] | |

| 36,966 | 0.51% | 2018 | [41] | |

| 6,855,082 | 94.66% | 2011 | [citation needed] | |

| 28,406 | 0.39% | 2016 | [42] | |

| Total | 7,211,537 |

Sociolinguistics[edit]

Afrikaans is also widely spoken in Namibia. Before independence, Afrikaans had equal status with German as an official language. Since independence in 1990, Afrikaans has had constitutional recognition as a national, but not official, language.[43][44]There is a much smaller number of Afrikaans speakers among Zimbabwe's white minority, as most have left the country since 1980. Afrikaans was also a medium of instruction for schools inBophuthatswana,an Apartheid-eraBantustan.[45]Eldoretin Kenya was founded by Afrikaners.[46]

In 1976, secondary-school pupils inSowetobegana rebellionin response to the government's decision that Afrikaans be used as the language of instruction for half the subjects taught in non-White schools (with English continuing for the other half). AlthoughEnglishis themother tongueof only 8.2% of the population, it is the language most widely understood, and thesecond languageof a majority of South Africans.[47]Afrikaans is more widely spoken than English in the Northern and Western Cape provinces, several hundred kilometres from Soweto.[48]The Black community's opposition to Afrikaans and preference for continuing English instruction was underlined when the government rescinded the policy one month after the uprising: 96% of Black schools chose English (over Afrikaans or native languages) as the language of instruction.[48]Afrikaans-medium schools were also accused of using language policy to deter Black African parents.[49]Some of these parents, in part supported by provincial departments of education, initiated litigation which enabled enrolment with English as language of instruction. By 2006 there were 300 single-medium Afrikaans schools, compared to 2,500 in 1994, after most converted to dual-medium education.[49]Due to Afrikaans being viewed as the "language of the white oppressor" by some, pressure has been increased to remove Afrikaans as a teaching language in South African universities, resulting in bloody student protests in 2015.[50][51][52]

UnderSouth Africa's Constitutionof 1996, Afrikaans remains anofficial language,and has equal status to English and nine other languages. The new policy means that the use of Afrikaans is now often reduced in favour of English, or to accommodate the other official languages. In 1996, for example, theSouth African Broadcasting Corporationreduced the amount of television airtime in Afrikaans, whileSouth African Airwaysdropped its Afrikaans nameSuid-Afrikaanse Lugdiensfrom itslivery.Similarly, South Africa'sdiplomatic missionsoverseas now display the name of the country only in English and their host country's language, and not in Afrikaans. Meanwhile, theconstitution of the Western Cape,which went into effect in 1998, declares Afrikaans to be an official language of the province alongsideEnglishandXhosa.[53]

The Afrikaans-language general-interest family magazineHuisgenoothas the largest readership of any magazine in the country.[54]

When the British design magazineWallpaperdescribed Afrikaans as "one of the world's ugliest languages" in its September 2005 article about themonument,[55]South African billionaireJohann Rupert(chairman of theRichemont Group), responded by withdrawing advertising for brands such asCartier,Van Cleef & Arpels,MontblancandAlfred Dunhillfrom the magazine.[56]The author of the article, Bronwyn Davies, was anEnglish-speaking South African.

Mutual intelligibility with Dutch[edit]

An estimated 90 to 95% of the Afrikaans lexicon is ultimately of Dutch origin,[57][58][59]and there are few lexical differences between the two languages.[60]Afrikaans has a considerably more regular morphology,[61]grammar, and spelling.[62]There is a high degree ofmutual intelligibilitybetween the two languages,[61][63][64]particularly in written form.[62][65][66]

Afrikaans acquired some lexical and syntactical borrowings from other languages such asMalay,Khoisan languages,Portuguese,[67]andBantu languages,[68]and Afrikaans has also been significantly influenced bySouth African English.[69]Dutch speakers are confronted with fewer non-cognates when listening to Afrikaans than the other way round.[66]Mutual intelligibility thus tends to be asymmetrical, as it is easier for Dutch speakers to understand Afrikaans than for Afrikaans speakers to understand Dutch.[66]

In general, mutual intelligibility between Dutch and Afrikaans is far better than between Dutch andFrisian[70]orbetweenDanishandSwedish.[66]The South African poet writerBreyten Breytenbach,attempting to visualise the language distance forAnglophonesonce remarked that the differences between (Standard) Dutch and Afrikaans are comparable to those between theReceived PronunciationandSouthern American English.[71]

Current status[edit]

| Province | 1996[72] | 2001[72] | 2011[72] | 2022[73] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Western Cape | 58.5% | 55.3% | 49.7% | 41.2% |

| Eastern Cape | 9.8% | 9.6% | 10.6% | 9.6% |

| Northern Cape | 57.2% | 56.6% | 53.8% | 54.6% |

| Free State | 14.4% | 11.9% | 12.7% | 10.3% |

| KwaZulu-Natal | 1.6% | 1.5% | 1.6% | 1.0% |

| North West | 8.8% | 8.8% | 9.0% | 5.2% |

| Gauteng | 15.6% | 13.6% | 12.4% | 7.7% |

| Mpumalanga | 7.1% | 5.5% | 7.2% | 3.2% |

| Limpopo | 2.6% | 2.6% | 2.6% | 2.3% |

| 14.4%[74] | 13.3%[75] | 13.5%[76] | 10.6%[73] |

Afrikaans is an official language of the Republic of South Africa and a recognised national language of the Republic of Namibia.Post-apartheid South Africahas seen a loss of preferential treatment by the government for Afrikaans, in terms of education, social events,media(TV and radio), and general status throughout the country, given that it now shares its place as official language with ten other languages. Nevertheless, Afrikaans remains more prevalent in the media – radio, newspapers and television[77]– than any of the other official languages, except English. More than 300 book titles in Afrikaans are published annually.[78]South African census figures suggest a decreasing number of first language Afrikaans speakers in South Africa from 13.5% in 2011 to 10.6% in 2022.[79]TheSouth African Institute of Race Relations(SAIRR) projects that a growing majority of Afrikaans speakers will beColoured.[80]Afrikaans speakers experience higher employment rates than other South African language groups, though as of 2012[update]half a million were unemployed.[81]

Despite the challenges of demotion and emigration that it faces in South Africa, the Afrikaans vernacular remains competitive, being popular inDSTVpay channels and several internet sites, while generating high newspaper and music CD sales. A resurgence in Afrikaans popular music since the late 1990s has invigorated the language, especially among a younger generation of South Africans. A recent trend is the increased availability of pre-school educational CDs and DVDs. Such media also prove popular with the extensive Afrikaans-speaking emigrant communities who seek to retain language proficiency in a household context.

Afrikaans-language cinema showed signs of new vigour in the early 21st century. The 2007 filmOuma se slim kind,the first full-length Afrikaans movie sincePaljasin 1998, is seen as the dawn of a new era in Afrikaans cinema. Several short films have been created and more feature-length movies, such asPoena is KoningandBakgat(both in 2008) have been produced, besides the 2011 Afrikaans-language filmSkoonheid,which was the first Afrikaans film to screen at theCannes Film Festival.The filmPlattelandwas also released in 2011.[82]The Afrikaans film industry started gaining international recognition via the likes of big Afrikaans Hollywood film stars, likeCharlize Theron(Monster) andSharlto Copley(District 9) promoting their mother tongue.

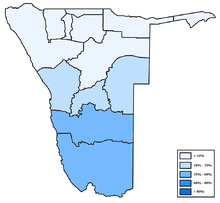

SABC3announced early in 2009 that it would increase Afrikaans programming due to the "growing Afrikaans-language market and [their] need for working capital as Afrikaans advertising is the only advertising that sells in the currentSouth African televisionmarket ". In April 2009, SABC3 started screening several Afrikaans-language programmes.[83]There is a groundswell movement within Afrikaans to be inclusive, and to promote itself along with the indigenous official languages. In Namibia, the percentage of Afrikaans speakers declined from 11.4% (2001 Census) to 10.4% (2011 Census). The major concentrations are inHardap(41.0%),ǁKaras(36.1%),Erongo(20.5%),Khomas(18.5%),Omaheke(10.0%),Otjozondjupa(9.4%),Kunene(4.2%), andOshikoto(2.3%).[84]

Some native speakers of Bantu languages andEnglishalso speak Afrikaans as a second language. It is widely taught in South African schools, with about 10.3 million second-language students.[1]

Afrikaans is offered at many universities outside South Africa, including in the Netherlands, Belgium, Germany, Poland, Russia and the United States.[85]

Grammar[edit]

In Afrikaans grammar, there is no distinction between theinfinitiveand present forms of verbs, with the exception of the verbs 'to be' and 'to have':

| infinitive form | present indicative form | Dutch | English |

|---|---|---|---|

| wees | is | zijnorwezen | be |

| hê | het | hebben | have |

In addition, verbs do notconjugatedifferently depending on the subject. For example,

| Afrikaans | Dutch | English |

|---|---|---|

| ek is | ik ben | I am |

| jy/u is | jij/u bent | you are (sing.) |

| hy/sy/dit is | hij/zij/het is | he/she/it is |

| ons is | wij zijn | we are |

| julle is | jullie zijn | you are (plur.) |

| hulle is | zij zijn | they are |

Only a handful of Afrikaans verbs have apreterite,namely the auxiliarywees( "to be" ), themodal verbs,and the verbdink( "to think" ). The preterite ofmag( "may" ) is rare in contemporary Afrikaans.

| Afrikaans | Dutch | English | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| present | past | present | past | present | past |

| ek is | ek was | ik ben | ik was | I am | I was |

| ek kan | ek kon | ik kan | ik kon | I can | I could |

| ek moet | ek moes | ik moet | ik moest | I must | (I had to) |

| ek wil | ek wou | ik wil | ik wilde/wou | I want to | I wanted to |

| ek sal | ek sou | ik zal | ik zou | I shall | I should |

| ek mag | (ek mog) | ik mag | ik mocht | I may | I might |

| ek dink | ek dog | ik denk | ik dacht | I think | I thought |

All other verbs use the perfect tense, het + past participle (ge-), for the past. Therefore, there is no distinction in Afrikaans betweenI drankandI have drunk.(In colloquial German, the past tense is also often replaced with the perfect.)

| Afrikaans | Dutch | English |

|---|---|---|

| ek het gedrink | ik dronk | I drank |

| ik heb gedronken | I have drunk |

When telling a longer story, Afrikaans speakers usually avoid the perfect and simply use the present tense, orhistorical present tenseinstead (as is possible, but less common, in English as well).

A particular feature of Afrikaans is its use of thedouble negative;it is classified in Afrikaans asontkennende vormand is something that is absent from the other West Germanic standard languages. For example,

- Afrikaans:Hy kannieAfrikaans praatnie,lit. 'He can not Afrikaans speak not'

- Dutch:Hij spreektgeenAfrikaans.

- English: He cannotspeak Afrikaans. / Hecan'tspeak Afrikaans.

Both French and San origins have been suggested for double negation in Afrikaans. While double negation is still found inLow Franconian dialectsinWest Flandersand in some "isolated" villages in the centre of the Netherlands (such asGarderen), it takes a different form, which is not found in Afrikaans. The following is an example:

- Afrikaans:Ek wil nie dit doen nie.*(lit.I want not this do not.)

- Dutch:Ik wil dit niet doen.

- English: I do not want to do this.

*Compare withEk wil dit nie doen nie,which changes the meaning to "I want not to do this." WhereasEk wil nie dit doen nieemphasizes a lack of desire to act,Ek wil dit nie doen nieemphasizes the act itself.

The-newas theMiddle Dutchway to negate but it has been suggested that since-nebecame highly non-voiced,nieornietwas needed to complement the-ne.With time the-nedisappeared in most Dutch dialects.

The double negative construction has been fully grammaticalised in standard Afrikaans and its proper use follows a set of fairly complex rules as the examples below show:

| Afrikaans | Dutch (literally translated) | More correct Dutch | Literal English | Idiomatic English |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ek het (nie) geweet dat hy (nie) sou kom (nie). | Ik heb (niet) geweten dat hij (niet) zou komen. | Ik wist (niet) dat hij (niet) zou komen. | I did (not) know that he would (not) come. | I did (not) know that he was (not) going to come. |

| Hy sal nie kom nie, want hy is siek.[n 3] | Hij zal niet komen, want hij is ziek. | Hij komt niet, want hij is ziek. | He will not come, as he is sick. | He is sick and is not going to come. |

| Dis (Dit is) nie so moeilik om Afrikaans te leer nie. | Het is niet zo moeilijk (om) Afrikaans te leren. | It is not so difficult to learn Afrikaans. | ||

A notable exception to this is the use of the negating grammar form that coincides with negating the Englishpresent participle.In this case there is only a single negation.

- Afrikaans:Hy is in die hospitaal, maar hy eet nie.

- Dutch:Hij is in het ziekenhuis, maar hij eet niet.

- English: He is in [the] hospital, though he doesn't eat.

Certain words in Afrikaans would be contracted. For example,moet nie,which literally means "must not", usually becomesmoenie;although one does not have to write or say it like this, virtually all Afrikaans speakers will change the two words tomoeniein the same way asdo notis contracted todon'tin English.

The Dutch wordhet( "it" in English) does not correspond tohetin Afrikaans. The Dutch words corresponding to Afrikaanshetareheb,hebt,heeftandhebben.

| Afrikaans | Dutch | English |

|---|---|---|

| het | heb, hebt, heeft, hebben | have, has |

| die | de, het | the |

| dit | het | it |

Phonology[edit]

Vowels[edit]

| Front | Central | Back | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| unrounded | rounded | unrounded | rounded | |||||||

| short | long | short | long | short | long | short | long | short | long | |

| Close | i | (iː) | y | yː | u | (uː) | ||||

| Mid | e | eː | ə | (əː) | œ | (œː) | o | (oː) | ||

| Near-open | (æ) | (æː) | ||||||||

| Open | a | ɑː | ||||||||

- As phonemes,/iː/and/uː/occur only in the wordsspieël/spiːl/'mirror' andkoeël/kuːl/'bullet', which used to be pronounced with sequences/i.ə/and/u.ə/,respectively. In other cases,[iː]and[uː]occur as allophones of, respectively,/i/and/u/before/r/.[88]

- /y/is phonetically long[yː]before/r/.[89]

- /əː/is always stressed and occurs only in the wordwîe'wedges'.[90]

- The closest unrounded counterparts of/œ,œː/are central/ə,əː/,rather than front/e,eː/.[91]

- /œː,oː/occur only in a few words.[92]

- [æ]occurs as an allophone of/e/before/k,χ,l,r/,though this occurs primarily dialectally, most commonly in the formerTransvaalandFree Stateprovinces.[93]

Diphthongs[edit]

| Starting point | Ending point | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Front | Central | Back | ||

| Mid | unrounded | ɪø,əi | ɪə | |

| rounded | œi,ɔi | ʊə | œu | |

| Open | unrounded | ai,ɑːi | ||

- /ɔi,ai/occur mainly in loanwords.[96]

Consonants[edit]

| Labial | Alveolar | Post- alveolar |

Dorsal | Glottal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n | ŋ | |||

| Plosive | voiceless | p | t | t͡ʃ | k | |

| voiced | b | d | (d͡ʒ) | (ɡ) | ||

| Fricative | voiceless | f | s | ʃ(ɹ̠̊˔) | χ | |

| voiced | v | (z) | ʒ | ɦ | ||

| Approximant | l | j | ||||

| Rhotic | r~ɾ~ʀ~ʁ | |||||

- Allobstruentsat the ends of words aredevoiced,so that e.g. a final/d/is realized as[t].[97]

- /ɡ,dʒ,z/occur only in loanwords.[ɡ]is also an allophone of/χ/in some environments.[98]

- /χ/is most often uvular[χ~ʀ̥].[99][100][101]Velar[x]occurs only in some speakers.[100]

- The rhotic is usually an alveolar trill[r]or tap[ɾ].[102]In some parts of the formerCape Province,it is realized uvularly, either as a trill[ʀ]or a fricative[ʁ].[103]

Dialects[edit]

Following early dialectal studies of Afrikaans, it was theorised that three main historical dialects probably existed after the Great Trek in the 1830s. These dialects are the Northern Cape, Western Cape, and Eastern Cape dialects.[104]Northern Cape dialect may have resulted from contact between Dutch settlers and theKhoekhoepeople between the Great Karoo and the Kunene, and Eastern Cape dialect between the Dutch and the Xhosa. Remnants of these dialects still remain in present-day Afrikaans, although the standardising effect of Standard Afrikaans has contributed to a great levelling of differences in modern times.[105][better source needed]

There is also a prisoncant,known asSabela,which is based on Afrikaans, yet heavily influenced byZulu.This language is used as a secret language in prison and is taught to initiates.[105]

Patagonian Afrikaans dialect[edit]

Patagonian Afrikaansis a distinct dialect of Afrikaans is spoken by the 650-strongSouth African communityofArgentina,in the region ofPatagonia.[106]

Influences on Afrikaans from other languages[edit]

Malay[edit]

Due to the early settlement of aCape Malaycommunity inCape Town,who are now known asColoureds,numerousClassical Malaywords were brought into Afrikaans. Some of these words entered Dutch via people arriving from what is now known asIndonesiaas part of their colonial heritage. Malay words in Afrikaans include:[107]

- baie,which means 'very'/'much'/'many' (frombanyak) is a very commonly used Afrikaans word, different from its Dutch equivalentveelorerg.

- baadjie,Afrikaans forjacket(frombaju,ultimately fromPersian), used where Dutch would usejasorvest.The wordbaadjein Dutch is now considered archaic and only used in written, literary texts.

- bobotie,a traditional Cape-Malay dish, made from spicedminced meatbaked with an egg-based topping.

- piesang,which meansbanana.This is different from the common Dutch wordbanaan.The Indonesian wordpisangis also used in Dutch, though usage is less common.

- piering,which meanssaucer(frompiring,also from Persian).

Portuguese[edit]

Some words originally came from Portuguese such assambreel( "umbrella" ) from the Portuguesesombreiro,kraal( "pen/cattle enclosure" ) from the Portuguesecurralandmielie( "corn", frommilho). Some of these words also exist in Dutch, likesambreel"parasol",[108]though usage is less common and meanings can slightly differ.

Khoisan languages[edit]

- dagga,meaningcannabis[107]

- geitjie,meaninglizard,diminutive adapted from aKhoekhoeword[109]

- gogga,meaning insect, from theKhoisanxo-xo

- karos,blanket of animal hides

- kierie,walking stick fromKhoekhoe[109]

Some of these words also exist in Dutch, though with a more specific meaning:assegaaifor example means "South-African tribal javelin"[110]andkarosmeans "South-African tribal blanket of animal hides".[111]

Bantu languages[edit]

Loanwords fromBantu languagesin Afrikaans include the names of indigenous birds, such asmahemandsakaboela,and indigenous plants, such asmaroelaandtamboekie(gras).[112]

- fundi,from theZuluwordumfundimeaning "scholar" or "student",[113]but used to mean someone who is a student of/expert on a certain subject, i.e.He is a languagefundi.

- lobola,meaning bride price, from (and referring to)loboloof theNguni languages[114]

- mahem,thegrey crowned crane,known in Latin asBalearica regulorum

- maroela,medium-sizeddioecioustree known in Latin asSclerocarya birrea[115]

- tamboekiegras,species of thatching grass known asHyparrhenia[116]

- tambotie,deciduous tree also known by itsLatinname,Spirostachys africana[117]

- tjaila/tjailatyd,an adaption of the wordchaile,meaning "to go home" or "to knock off (from work)".[118]

French[edit]

The revoking of theEdict of Nanteson 22 October 1685 was a milestone in the history ofSouth Africa,for it marked the beginning of the greatHuguenotexodus fromFrance.It is estimated that between 250,000 and 300,000 Protestants left France between 1685 and 1700; out of these, according toLouvois,100,000 had received military training. A measure of the calibre of these immigrants and of their acceptance by host countries (in particular South Africa) is given byH. V. Mortonin his book:In Search of South Africa(London, 1948). The Huguenots were responsible for a great linguistic contribution to Afrikaans, particularly in terms of military terminology as many of them fought on the battlefields during the wars of theGreat Trek.

Most of the words in this list are descendants from Dutch borrowings from French, Old French or Latin, and are not direct influences from French on Afrikaans.

| Afrikaans | Dutch | French | English |

|---|---|---|---|

| advies | advies | avis | advice |

| alarm | alarm | alarme | alarm |

| ammunisie | ammunitie, munitie | munition | ammunition |

| amusant | amusant | amusant | funny |

| artillerie | artillerie | artillerie | artillery |

| ateljee | atelier | atelier | studio |

| bagasie | bagage | bagage | luggage |

| bastion | bastion | bastion | bastion |

| bataljon | bataljon | bataillon | battalion |

| battery | batterij | batterie | battery |

| biblioteek | bibliotheek | bibliothèque | library |

| faktuur | factuur | facture | invoice |

| fort | fort | fort | fort |

| frikkadel | frikandel | fricadelle | meatball |

| garnisoen | garnizoen | garnison | garrison |

| generaal | generaal | général | general |

| granaat | granaat | grenade | grenade |

| infanterie | infanterie | infanterie | infantry |

| interessant | interessant | intéressant | interesting |

| kaliber | kaliber | calibre | calibre |

| kanon | kanon | canon | cannon |

| kanonnier | kanonnier | canonier | gunner |

| kardoes | kardoes, cartouche | cartouche | cartridge |

| kaptein | kapitein | capitaine | captain |

| kolonel | kolonel | colonel | colonel |

| kommandeur | commandeur | commandeur | commander |

| kwartier | kwartier | quartier | quarter |

| lieutenant | lieutenant | lieutenant | lieutenant |

| magasyn | magazijn | magasin | magazine |

| manier | manier | manière | way |

| marsjeer | marcheer, marcheren | marcher | (to) march |

| meubels | meubels | meubles | furniture |

| militêr | militair | militaire | militarily |

| morsel | morzel | morceau | piece |

| mortier | mortier | mortier | mortar |

| muit | muit, muiten | mutiner | (to) mutiny |

| musket | musket | mousquet | musket |

| muur | muur | mur | wall |

| myn | mijn | mine | mine |

| offisier | officier | officier | officer |

| orde | orde | ordre | order |

| papier | papier | papier | paper |

| pionier | pionier | pionnier | pioneer |

| plafon | plafond | plafond | ceiling |

| plat | plat | plat | flat |

| pont | pont | pont | ferry |

| provoos | provoost | prévôt | chief |

| rondte | rondte, ronde | ronde | round |

| salvo | salvo | salve | salvo |

| soldaat | soldaat | soldat | soldier |

| tante | tante | tante | aunt |

| tapyt | tapijt | tapis | carpet |

| tros | tros | trousse | bunch |

Orthography[edit]

The Afrikaanswriting systemis based onDutch,using the 26 letters of theISO basic Latin Alpha bet,plus 16 additional vowels withdiacritics.Thehyphen(e.g. in a compound likesee-eend'sea duck'),apostrophe(e.g.ma's'mothers'), and awhitespace character(e.g. in multi-word units likeDooie See'Dead Sea') is part of theorthographyof words, while the indefinite articleʼnis aligature.All the Alpha bet letters, including those with diacritics, have capital letters asallographs;theʼndoes not have a capital letter allograph. This means that Afrikaans has 88graphemeswith allographs in total.

| Majuscule forms(also calleduppercaseorcapital letters) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | Á | Ä | B | C | D | E | É | È | Ê | Ë | F | G | H | I | Í | Î | Ï | J | K | L | M | N | O | Ó | Ô | Ö | P | Q | R | S | T | U | Ú | Û | Ü | V | W | X | Y | Ý | Z | |

| Minuscule forms(also calledlowercaseorsmall letters) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| a | á | ä | b | c | d | e | é | è | ê | ë | f | g | h | i | í | î | ï | j | k | l | m | n | ʼn | o | ó | ô | ö | p | q | r | s | t | u | ú | û | ü | v | w | x | y | ý | z |

In Afrikaans, many consonants are dropped from the earlier Dutch spelling. For example,slechts('only') in Dutch becomesslegsin Afrikaans. Also, Afrikaans and some Dutch dialects make no distinction between/s/and/z/,having merged the latter into the former; while the word for "south" is writtenzuidin Dutch, it is spelledsuidin Afrikaans (as well as dialectal Dutch writings) to represent this merger. Similarly, the Dutch digraphij,normally pronounced as/ɛi/,corresponds to Afrikaansy,except where it replaces the Dutchsuffix–lijkwhich is pronounced as/lək/,as inwaarschijnlijk>waarskynlik.

Another difference is the indefinite article,'nin Afrikaans andeenin Dutch. "A book" is'n boekin Afrikaans, whereas it is eithereen boekor'n boekin Dutch. This'nis usually pronounced as just aweak vowel,[ə],just like English "a".

Thediminutivesuffix in Afrikaans is-tjie,-djieor-ie,whereas in Dutch it is-tjeordje,hence a "bit" isʼnbietjiein Afrikaans andbeetjein Dutch.

The lettersc,q,x,andzoccur almost exclusively in borrowings from French, English,GreekandLatin.This is usually because words that hadcandchin the original Dutch are spelled withkandg,respectively, in Afrikaans. Similarly originalquandxare most often speltkwandks,respectively. For example,ekwatoriaalinstead ofequatoriaal,andekskuusinstead ofexcuus.

The vowels with diacritics in non-loanword Afrikaans are:á,ä,é,è,ê,ë,í,î,ï,ó,ô,ö,ú,û,ü,ý.Diacritics are ignored when Alpha betising, though they are still important, even when typing the diacritic forms may be difficult. For example,geëet( "ate" ) instead of the 3 e's alongside each other:*geeet,which can never occur in Afrikaans, orsê,which translates to "say", whereasseis a possessive form. The acute's (á,é,í,ó,ú, ý)primary function is to place emphasis on a word (i.e. for emphatic reasons), by adding it to the emphasised syllable of the word. For example,sál( "will" (verb)),néé('no'),móét( "must" ),hý( "he" ),gewéét( "knew" ). The acute is only placed on theiif it is the only vowel in the emphasised word:wil('want' (verb)) becomeswíl,butlui('lazy') becomeslúi.Only a few non-loan words are spelled with acutes, e.g.dié('this'),ná('after'),óf... óf('either... or'),nóg... nóg('neither... nor'), etc. Only four non-loan words are spelled with the grave:nè('yes?', 'right?', 'eh?'),dè('here, take this!' or '[this is] yours!'),hè('huh?', 'what?', 'eh?'), andappèl('(formal) appeal' (noun)).

Initial apostrophes[edit]

A few short words in Afrikaans take initial apostrophes. In modern Afrikaans, these words are always written in lower case (except if the entire line is uppercase), and if they occur at the beginning of a sentence, the next word is capitalised. Three examples of such apostrophed words are'k, 't, 'n.The last (the indefinite article) is the only apostrophed word that is common in modern written Afrikaans, since the other examples are shortened versions of other words (ekandhet,respectively) and are rarely found outside of a poetic context.[119]

Here are a few examples:

| Apostrophed version | Usual version | Translation | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 'k 't Dit gesê | Ek het dit gesê | I said it | Uncommon, more common:Ek't dit gesê |

| 't Jy dit geëet? | Het jy dit geëet? | Did you eat it? | Extremely uncommon |

| 'n Man loop daar | A man walks there | Standard Afrikaans pronounces'nas aschwavowel. |

The apostrophe and the following letter are regarded as two separate characters, and are never written using a single glyph, although a single character variant of the indefinite article appears in Unicode,ʼn.

Table of characters[edit]

For more on the pronunciation of the letters below, seeHelp:IPA/Afrikaans.

| Grapheme | IPA | Examples and Notes |

|---|---|---|

| a | /a/,/ɑː/ | appel('apple';/a/),tale('languages';/ɑː/). Represents/a/in closed syllables and/ɑː/in stressed open syllables |

| á | /a/, /ɑ:/ | ná(after) |

| ä | /a/, /ɑ:/ | sebraägtig('zebra-like'). The diaeresis indicates the start of new syllable. |

| aa | /ɑː/ | aap('monkey', 'ape'). Only occurs in closed syllables. |

| aai | /ɑːi/ | draai('turn') |

| ae | /ɑːə/ | vrae('questions'); the vowels belong to two separate syllables |

| ai | /ai/ | baie('many', 'much' or 'very'),ai(expression of frustration or resignation) |

| b | /b/,/p/ | boom('tree') |

| c | /s/,/k/ | Found only in borrowed words or proper nouns; the former pronunciation occurs before 'e', 'i', or 'y'; featured in the Latinate plural ending-ici(singular form-ikus) |

| ch | /ʃ/,/x/,/k/ | chirurg('surgeon';/ʃ/;typicallysjis used instead),chemie('chemistry';/x/),chitien('chitin';/k/). Found only in recent loanwords and in proper nouns |

| d | /d/,/t/ | dag('day'),deel('part', 'divide', 'share') |

| dj | /d͡ʒ/,/k/ | djati('teak'),broodjie('sandwich'). Used to transcribe foreign words for the former pronunciation, and in the diminutive suffix-djiefor the latter in words ending withd |

| e | /e(ː)/,/æ(ː)/,/ɪə/,/ɪ/,/ə/ | bed(/e/),mens('person', /eː/) (lengthened before/n/)ete('meal',/ɪə/and/ə/respectively),ek('I', /æ/),berg('mountain', /æː/) (lengthened before/r/)./ɪ/is the unstressed allophone of/ɪə/ |

| é | /e(ː)/,/æ(ː)/,/ɪə/ | dié('this'),mét('with', emphasised),ék('I; me', emphasised),wéét('know', emphasised) |

| è | /e/ | Found in loanwords (likecrèche) and proper nouns (likeEugène) where the spelling was maintained, and in four non-loanwords:nè('yes?', 'right?', 'eh?'),dè('here, take this!' or '[this is] yours!'),hè('huh?', 'what?', 'eh?'), andappèl('(formal) appeal' (noun)). |

| ê | /eː/,/æː/ | sê('to say'),wêreld('world'),lêer('file') (Allophonically/æː/before/(ə)r/) |

| ë | - | Diaeresis indicates the start of new syllable, thusë,ëeandëiare pronounced like 'e', 'ee' and 'ei', respectively |

| ee | /ɪə/ | weet('to know'),een('one') |

| eeu | /ɪu/ | leeu('lion'),eeu('century', 'age') |

| ei | /ei/ | lei('to lead') |

| eu | /ɪɵ/ | seun('son' or 'lad') |

| f | /f/ | fiets('bicycle') |

| g | /x/,/ɡ/ | /ɡ/exists as the allophone of/x/if at the end of a root word preceded by a stressed single vowel +/r/and suffixed with a schwa, e.g.berg('mountain') is pronounced as/bæːrx/,andbergeis pronounced as/bæːrɡə/ |

| gh | /ɡ/ | gholf('golf'). Used for/ɡ/when it is not an allophone of/x/;found only in borrowed words. If thehinstead begins the next syllable, the two letters are pronounced separately. |

| h | /ɦ/ | hael('hail'),hond('dog') |

| i | /i/,/ə/ | kind('child';/ə/),ink('ink';/ə/),krisis('crisis';/i/and/ə/respectively),elektrisiteit('electricity';/i/for all three; third 'i' is part of diphthong 'ei') |

| í | /i/, /ə/ | krísis('crisis', emphasised),dít('that', emphasised) |

| î | /əː/ | wîe(plural ofwig;'wedges' or 'quoins') |

| ï | /i/, /ə/ | Found in words such asbeïnvloed('to influence'). The diaeresis indicates the start of new syllable. |

| ie | /i(ː)/ | iets('something'),vier('four') |

| j | /j/ | julle(plural 'you') |

| k | /k/ | kat('cat'),kan('can' (verb) or 'jug') |

| l | /l/ | lag('laugh') |

| m | /m/ | man('man') |

| n | /n/ | nael('nail') |

| ʼn | /ə/ | indefinite articleʼn('a'), styled as a ligature (Unicode character U+0149) |

| ng | /ŋ/ | sing('to sing') |

| o | /o/,/ʊə/,/ʊ/ | op('up(on)';/o/),grote('size';/ʊə/),polisie('police';/ʊ/) |

| ó | /o/,/ʊə/ | óp('done, finished', emphasised),gróót('huge', emphasised) |

| ô | /oː/ | môre('tomorrow') |

| ö | /o/,/ʊə/ | Found in words such askoöperasie('co-operation'). The diaeresis indicates the start of new syllable, thusöis pronounced the same as 'o' based on the following remainder of the word. |

| oe | /u(ː)/ | boek('book'),koers('course', 'direction') |

| oei | /ui/ | koei('cow') |

| oo | /ʊə/ | oom('uncle' or 'sir') |

| ooi | /oːi/ | mooi('pretty', 'beautiful'),nooi('invite') |

| ou | /ɵu/ | By itself means ('guy'). Sometimes spelledouwin loanwords and surnames, for exampleLouw. |

| p | /p/ | pot('pot'),pers('purple' — or 'press' indicating the news media; the latter is often spelled with an <ê>) |

| q | /k/ | Found only in foreign words with original spelling maintained; typicallykis used instead |

| r | /r/ | rooi('red') |

| s | /s/,/z/,/ʃ/,/ʒ/ | ses('six'),stem('voice' or 'vote'),posisie('position',/z/for first 's',/s/for second 's'),rasioneel('rational',/ʃ/(nonstandard; formally /s/ is used instead)visuëel('visual',/ʒ/(nonstandard; /z/ is more formal) |

| sj | /ʃ/ | sjaal('shawl'),sjokolade('chocolate') |

| t | /t/ | tafel('table') |

| tj | /tʃ/,/k/ | tjank('whine like a dog' or 'to cry incessantly'). The latter pronunciation occurs in the common diminutive suffix"-(e)tjie" |

| u | /ɵ/,/y(ː)/ | stuk('piece'),unie('union'),muur('wall') |

| ú | /œ/, /y(:)/ | búk('bend over', emphasised),ú('you', formal, emphasised) |

| û | /ɵː/ | brûe('bridges') |

| ü | - | Found in words such asreünie('reunion'). The diaeresis indicates the start of a new syllable, thusüis pronounced the same asu,except when found in proper nouns and surnames from German, likeMüller. |

| ui | /ɵi/ | uit('out') |

| uu | /y(ː)/ | uur('hour') |

| v | /f/,/v/ | vis('fish'),visuëel('visual') |

| w | /v/,/w/ | water('water';/v/); allophonically/w/after obstruents within a root; an example:kwas('brush';/w/) |

| x | /z/,/ks/ | xifoïed('xiphoid';/z/),x-straal('x-ray';/ks/). |

| y | /əi/ | byt('bite') |

| ý | /əi/ | hý('he', emphasised) |

| z | /z/ | Zoeloe('Zulu'). Found only inonomatopoeiaand loanwords |

Sample text[edit]

Psalm 231983 translation:[120]

Die Here is my Herder, ek kom niks kort nie.

Hy laat my rus in groen weivelde. Hy bring my by waters waar daar vrede is.

Hy gee my nuwe krag. Hy lei my op die regte paaie tot eer van Sy naam.

Selfs al gaan ek deur donker dieptes, sal ek nie bang wees nie, want U is by my. In U hande is ek veilig.

Psalm 231953 translation:[121]

Die Here is my Herder, niks sal my ontbreek nie.

Hy laat my neerlê in groen weivelde; na waters waar rus is, lei Hy my heen.

Hy verkwik my siel; Hy lei my in die spore van geregtigheid, om sy Naam ontwil.

Al gaan ek ook in 'n dal van doodskaduwee, ek sal geen onheil vrees nie; want U is met my: u stok en u staf die vertroos my.

Lord's Prayer(Afrikaans New Living Version translation):[122]

Ons Vader in die hemel, laat u Naam geheilig word.

Laat u koninkryk kom.

Laat u wil hier op aarde uitgevoer word soos in die hemel.

Gee ons die porsie brood wat ons vir vandag nodig het.

En vergeef ons ons sondeskuld soos ons ook óns skuldenaars vergewe het.

Bewaar ons sodat ons nie aan verleiding sal toegee nie; maar bevry ons van die greep van die bose.

Want aan U behoort die koningskap,

en die krag,

en die heerlikheid,

vir altyd.

Amen.

Lord's Prayer(Original translation):[citation needed]

Onse Vader wat in die hemel is,

laat U Naam geheilig word;

laat U koninkryk kom;

laat U wil geskied op die aarde,

net soos in die hemel.

Gee ons vandag ons daaglikse brood;

en vergeef ons ons skulde

soos ons ons skuldenaars vergewe

en laat ons nie in die versoeking nie

maar verlos ons van die bose

Want aan U behoort die koninkryk

en die krag

en die heerlikheid

tot in ewigheid.

Amen

See also[edit]

- AardklopArts Festival

- Afrikaans literature

- Afrikaans speaking population in South Africa

- Arabic Afrikaans

- Handwoordeboek van die Afrikaanse Taal(Afrikaans Dictionary)

- Differences between Afrikaans and Dutch

- IPA/Afrikaans

- Klein Karoo Nasionale Kunstefees(Arts Festival)

- Languages of South Africa

- Languages of Zimbabwe § Afrikaans

- List of Afrikaans language poets

- List of Afrikaans singers

- List of English words of Afrikaans origin

- South African Translators' Institute

- Tsotsitaal

Notes[edit]

- ^Afrikaans borrowed from other languages such as Portuguese, German, Malay, Bantu, and Khoisan languages; seeSebba 1997,p. 160,Niesler, Louw & Roux 2005,p. 459.

90 to 95% of Afrikaans vocabulary is ultimately of Dutch origin; seeMesthrie 1995,p. 214,Mesthrie 2002,p. 205,Kamwangamalu 2004,p. 203,Berdichevsky 2004,p. 131,Brachin & Vincent 1985,p. 132. - ^For morphology; seeHolm 1989,p. 338,Geerts & Clyne 1992,p. 72. For grammar and spelling; seeSebba 1997,p. 161.

- ^kanwould be best used in this case becausekan niemeans cannot and since he is sick he is unable to come, whereassalis "will" in English and is thus not the best word choice.

References[edit]

Citations[edit]

- ^abAfrikaansatEthnologue(19th ed., 2016)

- ^Aarons & Reynolds, "South African Sign Language" in Monaghan (ed.),Many Ways to be Deaf: International Variation in Deaf Communities(2003).

- ^Wells, John C. (2008).Longman Pronunciation Dictionary(3rd ed.). Longman.ISBN978-1-4058-8118-0.

- ^Roach, Peter (2011).Cambridge English Pronouncing Dictionary(18th ed.). Cambridge University Press.ISBN978-0-521-15253-2.

- ^K. Pithouse, C. Mitchell, R. Moletsane, Making Connections: Self-Study & Social Action, p.91

- ^J. A. Heese (1971).Die herkoms van die Afrikaner, 1657–1867[The origin of the Afrikaner] (in Afrikaans). Cape Town: A. A. Balkema.OCLC1821706.OL5361614M.

- ^Herkomst en groei van het Afrikaans - G.G. Kloeke (1950)

- ^Heeringa, Wilbert; de Wet, Febe; van Huyssteen, Gerhard B. (2015). "The origin of Afrikaans pronunciation: a comparison to west Germanic languages and Dutch dialects".Stellenbosch Papers in Linguistics Plus.47.doi:10.5842/47-0-649.ISSN2224-3380.

- ^Standaard Afrikaans(PDF).Afrikaner Pers. 1948.Retrieved17 September2014.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ab"Afrikaans Language Courses in London".Keylanguages. Archived fromthe originalon 12 August 2007.Retrieved22 September2010.

- ^The changed spelling rule was introduced in article 1, rule 3, of the Dutch "orthography law" of 14 February 1947. In 1954 theWord list of the Dutch languagewhich regulates the spelling of individual words including the wordAfrikaanswas first published.Ministerie van Binnenlandse Zaken en Koninkrijksrelaties (21 February 1997)."Wet voorschriften schrijfwijze Nederlandsche taal".wetten.overheid.nl(in Dutch). Archived fromthe originalon 5 February 2021.Retrieved10 March2023.

- ^"Afrikaans".Online Etymology Dictionary.Douglas Harper.Retrieved24 January2020.

- ^abcd"Afrikaans".Omniglot.Retrieved22 September2010.

- ^"Afrikaans language".Encyclopædia Britannica.Archivedfrom the original on 31 August 2010.Retrieved22 September2010.

- ^Alatis; Hamilton; Tan, Ai-Hui (2002).Georgetown University Round Table on Languages and Linguistics 2000: Linguistics, Language and the Professions: Education, Journalism, Law, Medicine, and Technology.Washington, DC: University Press. p. 132.ISBN978-0-87840-373-8.

- ^Brown, Keith; Ogilvie, Sarah, eds. (2008).Concise Encyclopedia of Languages of the World.Oxford: Elsevier. p. 8.ISBN978-0-08-087774-7.

- ^den Besten, Hans (1989). "From Khoekhoe foreignertalk via Hottentot Dutch to Afrikaans: the creation of a novel grammar". In Pütz; Dirven (eds.).Wheels within wheels: papers of the Duisburg symposium on pidgin and creole languages.Frankfurt-am-Main: Peter Lang. pp. 207–250.

- ^Hammarström, Harald; Forke, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin; Bank, Sebastian, eds. (2020)."Hottentot Dutch".Glottolog4.3.

- ^Kaplan, Irving (1971).Area Handbook for the Republic of South Africa(PDF).pp. 46–771.

- ^James Louis Garvin, ed. (1933). "Cape Colony".Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ^Clark, Nancy L.; William H. Worger (2016).South Africa: The Rise and Fall of Apartheid(3rd ed.). Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge.ISBN978-1-138-12444-8.OCLC883649263.

- ^Worden, Nigel (2010).Slavery in Dutch South Africa.Cambridge University Press. pp. 40–43.ISBN978-0521152662.

- ^Thomason & Kaufman (1988),pp. 252–254.

- ^Thomason & Kaufman (1988),p. 256.

- ^abKaplan, R. B.; Baldauf, R. B."Language Planning & Policy: Language Planning and Policy in Africa: Botswana, Malawi, Mozambique and South Africa".Retrieved17 March2017.(registration required)

- ^"Afrikaans becomes the official language of the Union of South Africa".South African History Online.16 March 2011.Retrieved17 March2017.

- ^"Speech by the Minister of Art and Culture, N Botha, at the 30th anniversary festival of the Afrikaans Language Monument"(in Afrikaans).South African Department of Arts and Culture.10 October 2005. Archived fromthe originalon 4 June 2011.Retrieved28 November2009.

- ^Galasko, C. (November 2008). "The Afrikaans Language Monument".Spine.33(23).doi:10.1097/01.brs.0000339413.49211.e6.

- ^abTomasz, Kamusella; Finex, Ndhlovu (2018).The Social and Political History of Southern Africa's Languages.Palgrave Macmillan UK. pp. 17–18.ISBN978-1-137-01592-1.

- ^"Afrikaner".South African History Online.South African History Online (SAHO).Retrieved20 October2017.

- ^Bogaards, Attie H."Bybelstudies"(in Afrikaans). Archived fromthe originalon 10 October 2008.Retrieved23 September2008.

- ^"Afrikaanse Bybel vier 75 jaar"(in Afrikaans). Bybelgenootskap van Suid-Afrika. 25 August 2008. Archived fromthe originalon 9 June 2008.Retrieved23 September2008.

- ^"Bible Society of South Africa - Afrikaans Bible translation".bybelgenootskap.co.za.Archived fromthe originalon 25 July 2020.Retrieved30 May2020.

- ^Harbert, Wayne (2007).The Germanic Languages.Cambridge University Press. pp.17.ISBN978-0-521-80825-5.

- ^"Afrikaans is making a comeback in Argentina - along with koeksisters and milktart".Business Insider South Africa.Retrieved11 October2019.

- ^"ABS: Language used at Home by State and Territory".ABS.Retrieved28 June2022.

- ^"Census Profile, 2016 Census of Canada".8 February 2017.Retrieved8 August2019.

- ^"2011 Census: Detailed analysis - English language proficiency in parts of the United Kingdom, Main language and general health characteristics".Office for National Statistics.Retrieved20 January2018.

- ^"Language according to age and sex by region, 1990-2021".Statistics Finland.Retrieved10 January2023.

- ^"Press Statement Census 2016 Results Profile 7 - Migration and Diversity".CSO.21 September 2017.Archivedfrom the original on 19 November 2023.

- ^"Top 25 Languages in New Zealand".Ministry for Ethnic Communities.Archivedfrom the original on 6 May 2023.

- ^"2016 American Community Survey, 5-year estimates".Ipums USA.University of Minnesota.Retrieved10 March2023.

- ^Frydman, Jenna (2011). "A Critical Analysis of Namibia's English-only language policy". In Bokamba, Eyamba G. (ed.).Selected proceedings of the 40th Annual Conference on African Linguistics – African languages and linguistics today(PDF).Somerville, Massachusetts:Cascadilla Proceedings Project. pp. 178–189.ISBN978-1-57473-446-1.Archived(PDF)from the original on 9 October 2022.

- ^Willemyns, Roland (2013).Dutch: Biography of a Language.Oxford University Press. p. 232.ISBN978-0-19-985871-2.

- ^"Armoria patriæ – Republic of Bophuthatswana".Archived fromthe originalon 26 October 2009.

- ^Kamau, John (25 December 2020)."Eldoret, the town that South African Boers started".Business Daily.

- ^Govt info available online in all official languages – South Africa – The Good NewsArchived4 March 2016 at theWayback Machine.

- ^abBlack Linguistics: Language, Society and Politics in Africa and the Americas, by Sinfree Makoni, p. 120S.

- ^abLafon, Michel (2008)."Asikhulume! African Languages for all: a powerful strategy for spearheading transformation and improvement of the South African education system".In Lafon, Michel; Webb, Vic; Wa Kabwe Segatti, Aurelia (eds.).The Standardisation of African Languages: Language political realities.Institut Français d'Afrique du Sud Johannesburg. p. 47.Retrieved30 January2021– via HAL-SHS.

- ^Lynsey Chutel (25 February 2016)."South Africa: Protesting students torch university buildings".Stamford Advocate.Associated Press.Archived fromthe originalon 5 March 2016.

- ^"Studentenunruhen: Konflikte zwischen Schwarz und Weiß"[Student unrest: conflicts between black and white].Die Presse.25 February 2016.

- ^"Südafrika:" Unerklärliche "Gewaltserie an Universitäten"[South Africa: "Unexplained" violence at universities].Euronews.25 February 2016. Archived fromthe originalon 27 February 2016.Retrieved28 February2016.

- ^Constitution of the Western Cape, 1997, Chapter 1, section 5(1)(a)

- ^"Superbrands, visited on 21 March 2012"(PDF).Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 24 September 2015.

- ^Pressly, Donwald (5 December 2005)."Rupert snubs mag over Afrikaans slur".Business Africa.Archived fromthe originalon 16 February 2006.Retrieved10 March2023.

- ^Afrikaans stars join row over 'ugly language'Archived27 November 2011 at theWayback MachineCape Argus,10 December 2005.

- ^Mesthrie 1995,p. 214.

- ^Brachin & Vincent 1985,p. 132.

- ^Mesthrie 2002,p. 205.

- ^Sebba 1997,p. 161

- ^abHolm 1989,p. 338

- ^abSebba 1997

- ^Baker & Prys Jones 1997,p. 302

- ^Egil Breivik & Håkon Jahr 1987,p. 232

- ^Sebba 2007

- ^abcdGooskens 2007,pp. 445–467

- ^Language Standardization and Language Change: The Dynamics of Cape Dutch.John Benjamins Publishing Company. 2004. p. 22.ISBN9027218579.Retrieved10 November2008.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^Niesler, Louw & Roux 2005,pp. 459–474

- ^"Afrikaans: Standard Afrikaans".Lycos Retriever. Archived fromthe originalon 20 November 2011.

- ^ten Thije, Jan D.; Zeevaert, Ludger (2007).Receptive Multilingualism: Linguistic analyses, language policies and didactic concepts.John Benjamins Publishing Company. p. 17.ISBN978-9027219268.Retrieved19 May2010.

- ^S. Linfield, interview in Salmagundi; 2000.

- ^abc"Languages — Afrikaans".World Data Atlas. Archived fromthe originalon 4 October 2014.Retrieved17 September2014.

- ^ab[1]

- ^"2.8 Home language by province (percentages)".Statistics South Africa. Archived fromthe originalon 24 August 2007.Retrieved17 September2013.

- ^"Table 2.6: Home language within provinces (percentages)"(PDF).Census 2001 - Census in brief.Statistics South Africa. p. 16. Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 5 May 2005.Retrieved17 September2013.

- ^Census 2011: Census in brief(PDF).Pretoria: Statistics South Africa. 2012. p. 27.ISBN9780621413885.Archived(PDF)from the original on 13 May 2015.

- ^Oranje FM, Radio Sonder Grense, Jacaranda FM, Radio Pretoria, Rapport, Beeld, Die Burger, Die Son, Afrikaans news is run everyday; the PRAAG website is a web-based news service. On pay channels, it is provided as second language on all sports, Kyknet

- ^"Hannes van Zyl".Oulitnet.co.za. Archived fromthe originalon 28 December 2008.Retrieved1 October2009.

- ^"Census 2022: Statistical Release"(PDF).statssa.gov.za.10 October 2023. p. 9.Retrieved12 October2023.

- ^Prince, Llewellyn (23 March 2013)."Afrikaans se môre is bruin (Afrikaans' tomorrow is coloured)".Rapport.Archived fromthe originalon 31 March 2013.Retrieved25 March2013.

- ^Pienaar, Antoinette; Otto, Hanti (30 October 2012)."Afrikaans groei, sê sensus (Afrikaans growing according to census)".Beeld.Archived fromthe originalon 2 November 2012.Retrieved25 March2013.

- ^"Platteland Film".plattelanddiemovie.

- ^SABC3 "tests" Afrikaans programmingArchived16 July 2011 at theWayback Machine,Screen Africa,15 April 2009

- ^"Namibia 2011 Population & Housing Census Main Report"(PDF).Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 2 October 2013.

- ^[2][permanent dead link]

- ^Donaldson (1993),pp. 2–7.

- ^Wissing (2016).

- ^Donaldson (1993:4–6)

- ^Donaldson (1993),pp. 5–6.

- ^Donaldson (1993:4, 6–7)

- ^Swanepoel (1927:38)

- ^Donaldson (1993:7)

- ^Donaldson (1993:3, 7)

- ^Donaldson (1993:2, 8–10)

- ^Lass (1987:117–119)

- ^Donaldson (1993:10)

- ^Donaldson (1993),pp. 13–15.

- ^Donaldson (1993),pp. 13–14, 20–22.

- ^Den Besten (2012)

- ^ab"John Wells's phonetic blog: velar or uvular?".5 December 2011.Retrieved12 February2015.Only this source mentions the trilled realization.

- ^Bowerman (2004:939)

- ^Lass (1987),p. 117.

- ^Donaldson (1993),p. 15.

- ^They were named before the establishment of the currentWestern Cape,Eastern Cape,andNorthern Capeprovinces, and are not dialects of those provincesper se.

- ^ab"Afrikaans 101".Retrieved24 April2010.

- ^Szpiech, Ryan; W. Coetzee, Andries; García-Amaya, Lorenzo; Henriksen, Nicholas; L. Alberto, Paulina; Langland, Victoria (14 January 2019)."An almost-extinct Afrikaans dialect is making an unlikely comeback in Argentina".Quartz.

- ^ab"Afrikaans history and development. The Unique Language of South Africa".Safariafrica.co.za. Archived fromthe originalon 17 September 2011.Retrieved2 April2015.

- ^"Sambreel - (Zonnescherm)".Etymologiebank.nl.Retrieved2 April2015.

- ^abAustin, Peter, ed. (2008).One Thousand Languages: Living, Endangered, and Lost.University of California Press. p. 97.ISBN9780520255609.

- ^"ASSAGAAI".gtb.inl.nl.Archived fromthe originalon 20 September 2019.Retrieved7 October2019.

- ^"Karos II: Kros".Gtb.inl.nl.Retrieved2 April2015.

- ^Potgieter, D. J., ed. (1970). "Afrikaans".Standard Encyclopaedia of Southern Africa.Vol. 1. NASOU. p. 111.ISBN9780625003280.

- ^Döhne, J. L. (1857).A Zulu-Kafir Dictionary, Etymologically Explained... Preceded by an Introduction on the Zulu-Kafir Language.Cape Town: Printed at G.J. Pike's Machine Printing Office. p. 87.

- ^Samuel Doggie Ngcongwane (1985).The Languages We Speak.University of Zululand. p. 51.ISBN9780907995494.

- ^David Johnson; Sally Johnson (2002).Gardening with Indigenous Trees.Struik. p. 92.ISBN9781868727759.[permanent dead link]

- ^Strohbach, Ben J.; Walters, H.J.A. (Wally) (November 2015)."An overview of grass species used for thatching in the Zambezi, Kavango East and Kavango West Regions, Namibia".Dinteria(35). Windhoek, Namibia: 13–42.

- ^South African Journal of Ethnology.Vol. 22–24. Bureau for Scientific Publications of the Foundation for Education, Science and Technology. 1999. p. 157.

- ^Toward Freedom.Vol. 45–46. 1996. p. 47.

- ^"Retrieved 12 April 2010".101languages.net.26 August 2007. Archived fromthe originalon 15 October 2010.Retrieved22 September2010.

- ^"Soek / Vergelyk".Bybelgenootskap van Suid Afrika.Archived fromthe originalon 11 May 2020.Retrieved11 May2020.

- ^"Soek / Vergelyk".Bybelgenootskap van Suid Afrika.Archived fromthe originalon 11 May 2020.Retrieved11 May2020.

- ^"MATTEUS 6, NLV Bybel".Bible(in Afrikaans). YouVersion.Retrieved7 June2024.

Sources[edit]

- Adegbija, Efurosibina E. (1994),"Language Attitudes in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Sociolinguistic Overview",Multilingual Matters,ISBN9781853592393,retrieved10 November2008

- Alant, Jaco (2004),Parlons Afrikaans(in French),Éditions L'Harmattan,ISBN9782747576369,retrieved3 June2010

- Baker, Colin; Prys Jones, Sylvia (1997),Encyclopedia of bilingualism and bilingual education,Multilingual Matters Ltd.,ISBN9781853593628,retrieved19 May2010

- Berdichevsky, Norman (2004),Nations, language, and citizenship,Norman Berdichevsky,ISBN9780786427000,retrieved31 May2010

- Batibo, Herman (2005),"Language decline and death in Africa: causes, consequences, and challenges",Oxford Linguistics,Multilingual Matters Ltd,ISBN9781853598081,retrieved24 May2010

- Booij, Geert (1999),"The Phonology of Dutch.",Oxford Linguistics,Oxford University Press,ISBN0-19-823869-X,retrieved24 May2010

- Booij, Geert (2003),"Constructional idioms and periphrasis: the progressive construction in Dutch."(PDF),Paradigms and Periphrasis,University of Kentucky,archived fromthe original(PDF)on 3 May 2011,retrieved19 May2010

- Bowerman, Sean (2004), "White South African English: phonology", in Schneider, Edgar W.; Burridge, Kate; Kortmann, Bernd; Mesthrie, Rajend; Upton, Clive (eds.),A handbook of varieties of English,vol. 1: Phonology, Mouton de Gruyter, pp. 931–942,ISBN3-11-017532-0

- Brachin, Pierre; Vincent, Paul (1985),The Dutch Language: A Survey,Brill Archive,ISBN9004075933,retrieved3 November2008

- Bromber, Katrin; Smieja, Birgit (2004),"Globalisation and African languages: risks and benefits",Trends in Linguistics,Walter de Gruyter,ISBN9783110180992,retrieved28 May2010

- Brook Napier, Diane (2007), "Languages, language learning, and nationalism in South Africa", in Schuster, Katherine; Witkosky, David (eds.),Language of the land: policy, politics, identity,Studies in the history of education, Information Age Publishing,ISBN9781593116170,retrieved19 May2010

- Conradie, C. Jac (2005),"The final stages of deflection – The case of Afrikaans" het "",Historical Linguistics 2005,John Benjamins Publishing Company,ISBN9027247994,retrieved29 May2010

- Den Besten, Hans (2012), "Speculations of[χ]-elision and intersonorantic[ʋ]in Afrikaans ", in van der Wouden, Ton (ed.),Roots of Afrikaans: Selected Writings of Hans Den Besten,John Benjamins Publishing Company,pp. 79–93,ISBN978-90-272-5267-8

- Deumert, Ana (2002),"Standardization and social networks – The emergence and diffusion of standard Afrikaans",Standardization – Studies from the Germanic languages,John Benjamins Publishing Company,ISBN9027247471,retrieved29 May2010

- Deumert, Ana; Vandenbussche, Wim (2003),"Germanic standardizations: past to present",Trends in Linguistics,John Benjamins Publishing Company,ISBN9027218560,retrieved28 May2010

- Deumert, Ana (2004),Language Standardization and Language Change: The Dynamics of Cape Dutch,John Benjamins Publishing Company,ISBN9027218579,retrieved10 November2008

- de Swaan, Abram (2001),Words of the world: the global language system,A. de Swaan,ISBN9780745627489,retrieved3 June2010

- Domínguez, Francesc; López, Núria (1995),Sociolinguistic and language planning organizations,John Benjamins Publishing Company,ISBN9027219516,retrieved28 May2010

- Donaldson, Bruce C. (1993),A grammar of Afrikaans,Walter de Gruyter,ISBN9783110134261,retrieved28 May2010

- Egil Breivik, Leiv; Håkon Jahr, Ernst (1987),Language change: contributions to the study of its causes,Walter de Gruyter,ISBN9783110119954,retrieved19 May2010

- Geerts, G.; Clyne, Michael G. (1992),Pluricentric languages: differing norms in different nations,Walter de Gruyter,ISBN9783110128550,retrieved19 May2010

- Gooskens, Charlotte (2007),"The Contribution of Linguistic Factors to the Intelligibility of Closely Related Languages"(PDF),Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, Volume 28, Issue 6 November 2007,University of Groningen,pp. 445–467,archived(PDF)from the original on 9 October 2022,retrieved19 May2010

- Heeringa, Wilbert; de Wet, Febe (2007),The origin of Afrikaans pronunciation: a comparison to west Germanic languages and Dutch dialects(PDF),University of Groningen,pp. 445–467, archived fromthe original(PDF)on 29 April 2011,retrieved19 May2010

- Herriman, Michael L.; Burnaby, Barbara (1996),Language policies in English-dominant countries: six case studies,Multilingual Matters Ltd.,ISBN9781853593468,retrieved19 May2010

- Hiskens, Frans; Auer, Peter; Kerswill, Paul (2005),The study of dialect convergence and divergence: conceptual and methodological considerations.(PDF),Lancaster University,archived(PDF)from the original on 9 October 2022,retrieved19 May2010

- Holm, John A. (1989),Pidgins and Creoles: References survey,Cambridge University Press,ISBN9780521359405,retrieved19 May2010

- Jansen, Carel; Schreuder, Robert; Neijt, Anneke (2007),"The influence of spelling conventions on perceived plurality in compounds. A comparison of Afrikaans and Dutch."(PDF),Written Language & Literacy 10:2,Radboud University Nijmegen,archived fromthe original(PDF)on 29 April 2011,retrieved19 May2010

- Kamwangamalu, Nkonko M. (2004), "The language planning situation in South Africa", in Baldauf, Richard B.; Kaplan, Robert B. (eds.),Language planning and policy in Africa,Multilingual Matters Ltd.,ISBN9781853597251,retrieved31 May2010

- Langer, Nils; Davies, Winifred V. (2005),Linguistic purism in the Germanic languages,Walter de Gruyter,ISBN9783110183375,retrieved28 May2010

- Lass, Roger (1984), "Vowel System Universals and Typology: Prologue to Theory",Phonology Yearbook,1,Cambridge University Press:75–111,doi:10.1017/S0952675700000300,JSTOR4615383,S2CID143681251

- Lass, Roger (1987), "Intradiphthongal Dependencies", in Anderson, John; Durand, Jacques (eds.),Explorations in Dependency Phonology,Dordrecht: Foris Publications Holland, pp. 109–131,ISBN90-6765-297-0

- Machan, Tim William (2009),Language anxiety: conflict and change in the history of English,Oxford University Press,ISBN9780191552489,retrieved3 June2010

- McLean, Daryl; McCormick, Kay (1996), "English in South Africa 1940–1996", in Fishman, Joshua A.; Conrad, Andrew W.; Rubal-Lopez, Alma (eds.),Post-imperial English: status change in former British and American colonies, 1940–1990,Walter de Gruyter,ISBN9783110147544,retrieved31 May2010

- Mennen, Ineke; Levelt, Clara; Gerrits, Ellen (2006),"Acquisition of Dutch phonology: an overview",Speech Science Research Centre Working Paper WP10,Queen Margaret University College,retrieved19 May2010

- Mesthrie, Rajend (1995),Language and Social History: Studies in South African Sociolinguistics,New Africa Books,ISBN9780864862808,retrieved23 August2008

- Mesthrie, Rajend (2002),Language in South Africa,Cambridge University Press,ISBN9780521791052,retrieved18 May2010

- Myers-Scotton, Carol (2006),Multiple voices: an introduction to bilingualism,Blackwell Publishing,ISBN9780631219378,retrieved31 May2010

- Niesler, Thomas; Louw, Philippa; Roux, Justus (2005),"Phonetic analysis of Afrikaans, English, Xhosa and Zulu using South African speech databases"(PDF),Southern African Linguistics and Applied Language Studies,23(4): 459–474,doi:10.2989/16073610509486401,S2CID7138676,archived fromthe original(PDF)on 21 December 2012

- Palmer, Vernon Valentine (2001),Mixed jurisdictions worldwide: the third legal family,Vernon V. Palmer,ISBN9780521781541,retrieved3 June2010

- Page, Melvin Eugene; Sonnenburg, Penny M. (2003),Colonialism: an international, social, cultural, and political encyclopedia,Melvin E. Page,ISBN9781576073353,retrieved19 May2010

- Proost, Kristel (2006), "Spuren der Kreolisierung im Lexikon des Afrikaans", in Proost, Kristel; Winkler, Edeltraud (eds.),Von Intentionalität zur Bedeutung konventionalisierter Zeichen,Studien zur Deutschen Sprache (in German), Gunter Narr Verlag,ISBN9783823362289,retrieved3 June2010

- Réguer, Laurent Philippe (2004),Si loin, si proche...: Une langue européenne à découvrir: le néerlandais(in French),Sorbonne Nouvelle,ISBN9782910212308,retrieved3 June2010

- Sebba, Mark (1997),Contact languages: pidgins and creoles,Palgrave Macmillan,ISBN9780312175719,retrieved19 May2010

- Sebba, Mark (2007),Spelling and society: the culture and politics of orthography around the world,Cambridge University Press,ISBN9781139462020,retrieved19 May2010

- Simpson, Andrew (2008),Language and national identity in Africa,Oxford University Press,ISBN9780199286751,retrieved31 May2010

- Stell, Gerard (2008–2011),Mapping linguistic communication across colour divides: Black Afrikaans in Central South Africa,Vrije Universiteit Brussel,retrieved2 June2010

- Swanepoel, J. F. (1927),The sounds of Afrikaans. Their Dialectic Variations and the Difficulties They Present to an Englishman(PDF),Longmans, Green & Co,archived(PDF)from the original on 9 October 2022

- Thomason, Sarah Grey; Kaufman, Terrence (1988),Language Contact, Creolization, and Genetic Linguistics,University of California Press (published 1991),ISBN0-520-07893-4

- Webb, Victor N. (2002),Language in South Africa: the role of language in national transformation, reconstruction and development,IMPACT: Studies in Language and Society, vol. 14,John Benjamins Publishing Company,doi:10.1075/impact.14,ISBN9789027297631

- Webb, Victor N. (2003),"Language policy development in South Africa"(PDF),Centre for Research in the Politics of Language,University of Pretoria,archived fromthe original(PDF)on 9 December 2003

- Namibian Population Census (2001),Languages Spoken in Namibia,Government of Namibia, archived fromthe originalon 16 May 2010,retrieved28 May2010

- Wissing, Daan (2016),"Afrikaans phonology – segment inventory",Taalportaal,archived fromthe originalon 15 April 2017,retrieved16 April2017

- CIA (2010),The World Factbook (CIA) — Namibia,Central Intelligence Agency,retrieved28 May2010

Further reading[edit]

- Grieshaber, Nicky. 2011.Diacs and Quirks in a Nutshell – Afrikaans spelling explained.Pietermaritzburg.ISBN978-0-620-51726-3;e-ISBN978-0-620-51980-9.

- Roberge, P. T. (2002), "Afrikaans – considering origins",Language in South Africa,Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press,ISBN0-521-53383-X

- Thomas, C. H. (1899),"Boer language",Origin of the Anglo-Boer War revealed,London, England: Hodder and Stoughton

External links[edit]

- afrikaans

- Afrikaans English Online Dictionary at Hablaa(archived 4 June 2012)

- Afrikaans-English Online Dictionary at majstro

- Learn Afrikaans Online(Open Learning Environment)

- Federasie van Afrikaanse Kultuurvereniginge (FAK)– Federation of Afrikaans Cultural Associations

- Dutch Writers from South Africa: A Cultural-Historical Study, Part Ifrom theWorld Digital Library

- Afrikaans Literature and LanguageWeb dossier African Studies Centre, Leiden (2011)