Syria (region)

Syria (Sham)

| |

|---|---|

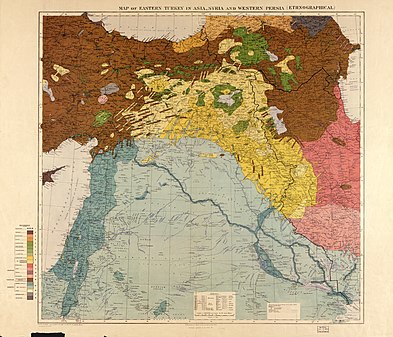

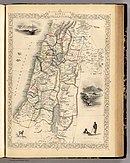

Map ofOttoman Syriain 1851, by Henry Warren | |

| Coordinates:33°N36°E/ 33°N 36°E | |

| Countries | |

Syria[a]orSham(Arabic:ٱلشَّام,romanized:Ash-Shām) is ahistorical regionlocated east of theMediterranean SeainWest Asia,broadly synonymous with theLevant.[3]Other synonyms areGreater SyriaorSyria-Palestine.[2]The region boundaries have changed throughout history. However, in modern times, the term "Syria" alone is used to refer to theSyrian Arab Republic.

The term is originally derived fromAssyria,an ancient civilization centered in northernMesopotamia,modern-dayIraq.[4][5]During theHellenistic period,the term Syria was applied to the entire Levant asCoele-Syria.UnderRoman rule,the term was used to refer to theprovince of Syria,later divided intoSyria PhoeniciaandCoele Syria,and to the province ofSyria Palaestina.Under the Byzantines, the provinces ofSyria Primaand Syria Secunda emerged out of Coele Syria. After theMuslim conquest of the Levant,the term was superseded by the Arabic equivalentShām,and under theRashidun,Umayyad,Abbasid,andFatimid caliphates,Bilad al-Shamwas the name of a metropolitan province encompassing most of the region. In the 19th century, the name Syria was revived in its modem Arabic form to denote the whole of Bilad al-Sham, either asSuriyahor the modern formSuriyya,which eventually replaced the Arabic name of Bilad al-Sham.[6]

AfterWorld War I,the boundaries of the region were last defined in modern times by the proclamation of and subsequent definition by French and British mandatory agreement. The area was passed to French and British Mandates followingWorld War Iand divided intoGreater Lebanon,various states underMandatory French rule,British-controlledMandatory Palestineand theEmirate of Transjordan.The term Syria itself was applied to several mandate states under French rule and the contemporaneous but short-livedArab Kingdom of Syria.The Syrian-mandate states were gradually unified as theState of Syriaand finally became the independent Syria in 1946. Throughout this period,pan-Syrian nationalistsadvocated for the creation of a Greater Syria.

Etymology and evolution of the term

[edit]Several sources indicate that the nameSyriaitself is derived fromLuwianterm "Sura/i", and the derivativeancient Greekname:Σύριοι,Sýrioi,orΣύροι,Sýroi,both of which originally derived from Aššūrāyu (Assyria) in northernMesopotamia,modern-dayIraq and greater Syria[4][5][7][8]ForHerodotusin the 5th century BC, Syria extended as far north as the Halys (the modernKızılırmak River) and as far south as Arabia and Egypt. ForPliny the ElderandPomponius Mela,Syria covered the entireFertile Crescent.

InLate Antiquity,"Syria" meant a region located to the east of theMediterranean Sea,west of theEuphrates River,north of theArabian Desertand south of theTaurus Mountains,[9]thereby including modernSyria,Lebanon,Jordan,Israel,Palestine,and parts of Southern Turkey, namely theHatay Provinceand the western half of theSoutheastern Anatolia Region.This late definition is equivalent to the region known inClassical Arabicby the nameash-Shām(Arabic:ٱَلشَّام/ʔaʃ-ʃaːm/,[10]which meansthe north [country][10](from the rootšʔmArabic:شَأْم"left, north" )). After theIslamic conquest of Byzantine Syriain the 7th centuryCE,the nameSyriafell out of primary use in the region itself, being superseded by the Arabic equivalentShām,but survived in its original sense in Byzantine and Western European usage, and in Syriac Christian literature.[6]In the 19th century the name Syria was revived in its modern Arabic form to denote the whole ofBilad al-Sham,either asSuriyahor the modern formSuriyya,which eventually replaced the Arabic name of Bilad al-Sham.[6]AfterWorld War I,the name Syria was applied to theFrench Mandate for Syria and the Lebanonand the contemporaneous but short-livedArab Kingdom of Syria.

Geography

[edit]

In the most common historical sense, 'Syria' refers to the entire northernLevant,includingAlexandrettaand the Ancient City ofAntiochor in an extended sense the entire Levant as far south asRoman Egypt,includingMesopotamia.The area of "Greater Syria" (سُوْرِيَّة ٱلْكُبْرَىٰ,Sūrīyah al-Kubrā); also called "Natural Syria" (سُوْرِيَّة ٱلطَّبِيْعِيَّة,Sūrīyah aṭ-Ṭabīʿīyah) or "Northern Land" (بِلَاد ٱلشَّام,Bilād ash-Shām),[1]extends roughly over theBilad al-Shamprovince of the medieval Arabcaliphates,encompassing theEastern Mediterranean(or Levant) and Western Mesopotamia. TheMuslim conquest of the Levantin the seventh century gave rise to this province, which encompassed much of the region of Syria, and came to largely overlap with this concept. Other sources indicate that the term Greater Syria was coined duringOttoman rule,after 1516, to designate the approximate area included in present-dayPalestine,Syria, Jordan, Lebanon.[11]

The uncertainty in the definition of the extent of "Syria" is aggravated by the etymological confusion of the similar-sounding namesSyriaandAssyria.The question of the etymological identity of the two names remains open today, but regardless of etymology, both were thought of as interchangeable around the time of Herodotus.[12]However, by the time of theRoman Empire,'Syria' and 'Assyria' began to refer to two separate entities,Roman SyriaandRoman Assyria.

Killebrew and Steiner, treating the Levant as the Syrian region, gave the boundaries of the region as such: theMediterranean Seato the west, theArabian Desertto the south, Mesopotamia to the east, and theTaurus MountainsofAnatoliato the north.[3]The Muslim geographerMuhammad al-Idrisivisited the region in 1150 and assigned the northern regions ofBilad al-Shamas the following:

In the Levantine sea are two islands:Rhodesand Cyprus; and in Levantine lands: Antarsus,Laodice,Antioch,Mopsuhestia,Adana,Anazarbus,Tarsus,Circesium,Ḥamrtash,Antalya,al-Batira, al-Mira,Macri,Astroboli; and in the interior lands:Apamea,Salamiya,Qinnasrin,al-Castel,Aleppo,Resafa,Raqqa,Rafeqa, al-Jisr,Manbij,Mar'ash,Saruj,Ḥarran,Edessa,Al-Ḥadath,Samosata,Malatiya,Ḥusn Mansur, Zabatra, Jersoon, al-Leen, al-Bedandour, Cirra and Touleb.

ForPliny the ElderandPomponius Mela,Syria covered the entireFertile Crescent.InLate Antiquity,"Syria" meant a region located to the east of theMediterranean Sea,west of theEuphrates River,north of the Arabian Desert, and south of theTaurus Mountains,[9]thereby including modern Syria, Lebanon, Jordan, Israel, the State of Palestine, and theHatay Provinceand the western half of theSoutheastern Anatolia Regionof southern Turkey. This late definition is equivalent to the region known inClassical Arabicby the nameash-Shām(ٱلشَّام/ʔaʃ-ʃaːm/),[10]which meansthe north [country][10](from the rootšʔmشَأْم"left, north" ). After theIslamic conquest of Byzantine Syriain the seventh century, the nameSyriafell out of primary use in the region itself, being superseded by the Arabic equivalentBilād ash-Shām( "Northern Land'" ), but survived in its original sense in Byzantine and Western European usage, and inSyriac Christianliterature. In the 19th century, the name Syria was revived in its modern Arabic form to denote the whole of Bilad al-Sham, either asSuriyahor the modern formSuriyya,which eventually replaced the Arabic name of Bilad al-Sham.[6]AfterWorld War I,the name 'Syria' was applied to theFrench Mandate for Syria and the Lebanon,and the contemporaneous but short-livedArab Kingdom of Syria.

Today, thelargest metropolitan areas in the regionareAmman,Tel Aviv,Damascus,Beirut,AleppoandGaza City.

| Rank | City | Country | Metropolitan Population |

City Population |

Image |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Amman | Jordan | 4,642,000 | 4,061,150 |

|

| 2 | Tel Aviv | Israel | 3,954,500 | 438,818 |

|

| 3 | Damascus | Syria | 2,900,000 | 2,078,000 |

|

| 4 | Beirut | Lebanon | 2,200,000 | 361,366 |

|

| 5 | Aleppo | Syria | 2,098,210 | 2,098,210 |

|

| 6 | Gaza City | Palestine | 2,047,969 | 590,481 |

|

Etymology

[edit]Syria

[edit]Several sources indicate that the nameSyriaitself is derived fromLuwianterm "Sura/i", and the derivativeancient Greekname:Σύριοι,Sýrioi,orΣύροι,Sýroi,both of which originally derived from Aššūrāyu (Assyria) in northernMesopotamia,modern-dayIraq[4][5]However, during theSeleucid Empire,this term was also applied toThe Levant,and henceforth the Greeks applied the term without distinction between theAssyriansof Mesopotamia andArameansof the Levant.[4][7][8]

The oldest attestation of the name 'Syria' is from the 8th century BC in a bilingual inscription inHieroglyphic LuwianandPhoenician.In this inscription, the Luwian wordSura/iwas translated to Phoenicianʔšr"Assyria."[4]ForHerodotusin the 5th century BC, Syria extended as far north as the Halys (the modernKızılırmak River) and as far south as Arabia and Egypt.

The name 'Syria' derives from theancient Greekname for Assyrians,Greek:ΣύριοιSyrioi,which the Greeks applied without distinction to various Near Eastern peoples living under the rule ofAssyria.Modern scholarship confirms the Greek word traces back to the cognateGreek:Ἀσσυρία,Assyria.[13]

The classical Arabic pronunciation of Syria isSūriya(as opposed to theModern Standard ArabicpronunciationSūrya). That name was not widely used among Muslims before about 1870, but it had been used by Christians earlier. According to theSyriac Orthodox Church,"Syrian" meant "Christian" inearly Christianity.[citation needed]In English, "Syrian" historically meant aSyrian Christiansuch asEphrem the Syrian.Following the declaration of Syria in 1936, the term "Syrian" came to designate citizens of that state, regardless of ethnicity. The adjective "Syriac" (suryāniسُرْيَانِي) has come into common use since as anethnonymto avoid the ambiguity of "Syrian".

Currently, the Arabic termSūriyausually refers to the modern state of Syria, as opposed to the historical region of Syria.

Shaam

[edit]Greater Syria has been widely known asAsh-Shām.The term etymologically in Arabic means "the left-hand side" or "the north", as someone in the Hejaz facing east, oriented to the sunrise, will find the north to the left. This is contrasted with the name of Yemen (اَلْيَمَنal-Yaman), correspondingly meaning "the right-hand side" or "the south". The variationش ء م(š-ʾ-m), of the more typicalش م ل(š-m-l),is also attested inOld South Arabian,𐩦𐩱𐩣(s²ʾm), with the same semantic development.[10][14]

The root ofShaam,ش ء م(š-ʾ-m) also has connotations of unluckiness, which is traditionally associated with the left-hand and with the colder north-winds. Again this is in contrast with Yemen, with felicity and success, and the positively-viewed warm-moist southerly wind; a theory for the etymology ofArabia Felixdenoting Yemen, by translation of that sense.[citation needed]

The Shaam region is sometimes defined as the area that was dominated byDamascus,long an important regional center.[citation needed]In fact, the wordAsh-Sām,on its own, can refer to the city ofDamascus.[15]Continuing with the similar contrasting theme,Damascuswas the commercial destination and representative of the region in the same waySanaaheld for the south.

Quran 106:2alludes to this practice of caravans traveling to Syria in the summer, to avoid the colder weather, and to likewise sell commodities in Yemen in the winter.[16][17]

There is no connection with the name Shem, son of Noah, whose name usually appears in Arabic asسَامSām,with a different initial consonant and without any internalglottal stop.Despite this, there has been a long-standing folk association between the two names and even the region, as most of the claimed Biblical descendants of Shem have been historically placed in the vicinity.[citation needed]

Historically,Baalshamin(Imperial Aramaic:ܒܥܠ ܫܡܝܢ,romanized:Ba'al Šamem,lit. 'Lord of Heaven(s)'),[18][19]was aSemiticsky godinCanaan/Phoeniciaand ancientPalmyra.[20][21]Hence, Sham refers to (heavenorsky). Moreover; in theHebrew language,sham(שָׁמַ)is derived fromAkkadianšamûmeaning "sky".[22]For instance, the Hebrew word for theSunisshemesh,where "shem/sham" fromshamayim[b](Akkadian:šamû) means "sky" andesh(Akkadian:išātu) means "fire", i.e. "sky-fire".[citation needed]

Demographics

[edit]| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 14 | 4,300,000 | — |

| 164 | 4,800,000 | +11.6% |

| 500 | 4,127,000 | −14.0% |

| 900 | 3,120,000 | −24.4% |

| 1200 | 2,700,000 | −13.5% |

| 1500 | 1,500,000 | −44.4% |

| 1700 | 2,028,000 | +35.2% |

| 1897 | 3,231,874 | +59.4% |

| 1914 | 3,448,356 | +6.7% |

| 1922 | 3,198,951 | −7.2% |

| Source:[23][24][25][26] | ||

The largest religious group in the Levant areMuslimsand the largest ethnic group areArabs.Levantines predominantly speakLevantine Arabic,who derive their ancestry from the manyancient Semitic-speaking peopleswho inhabited theancient Near Eastduring theBronzeandIron Ages.[27]Others such asBedouinArabs inhabit theSyrian Desertand Naqab, and speak a dialect known asBedouin Arabicthat originated inArabian Peninsula.Other minor ethnic groups in the Levant includeCircassians,Chechens,Turks,Turkmens,Assyrians,Kurds,NawarsandArmenians.

Islambecame the predominant religion in the region after theMuslim conquest of the Levantin the 7th century.[28][29]The majority of Levantine Muslims areSunniwithAlawiteandShia(TwelverandNizari Ismaili) minorities. Alawites and Ismaili Shiites mainly inhabitHatayand theSyrian Coastal Mountain Range,while Twelver Shiites are mainly concentrated in parts ofLebanon.

Levantine Christian groups are plenty and includeGreek Orthodox(Antiochian Greek),Syriac Orthodox,Eastern Catholic(Syriac Catholic,MelkiteandMaronite),Roman Catholic(Latin),Nestorian,andProtestant.Armeniansmostly belong to theArmenian Apostolic Church.There are alsoLevantines or Franco-Levantineswho adhere toRoman Catholicism.There are alsoAssyriansbelonging to theAssyrian Church of the Eastand theChaldean Catholic Church.[30]

Other religious groups in the Levant includeJews,Samaritans,YazidisandDruze.[31]

History

[edit]| History ofSyria |

|---|

|

| Prehistory |

| Bronze Age |

| Antiquity |

| Middle Ages |

|

| Early modern |

|

| Modern |

|

| Related articles |

| Timeline |

|

|

Ancient Syria

[edit]HerodotususesAncient Greek:Συρίαto refer to the stretch of land from the Halys river, includingCappadocia(The Histories, I.6) in today's Turkey to the Mount Casius (The Histories II.158), which Herodotus says is located just south of Lake Serbonis (The Histories III.5). According to Herodotus various remarks in different locations, he describes Syria to include the entire stretch of Phoenician coastal line as well as cities such Cadytis (Jerusalem) (The Histories III.159).[12]

Hellenistic Syria

[edit]In Greek usage,SyriaandAssyriawere used almost interchangeably, but in theRoman Empire,SyriaandAssyriacame to be used as distinct geographical terms. "Syria" in the Roman Empire period referred to "those parts of the Empire situated between Asia Minor and Egypt", i.e. the westernLevant,while "Assyria" was part of thePersian Empire,and only very briefly came under Roman control (116–118 AD, marking the historical peak ofRoman expansion).

Roman Syria

[edit]

In the Roman era, the term Syria is used to comprise the entire northern Levant and has an uncertain border to the northeast thatPliny the Elderdescribes as including, from west to east, theKingdom of Commagene,Sophene,andAdiabene,"formerly known as Assyria".[32]

Various writers used the term to describe the entire Levant region during this period; the New Testament used the name in this sense on numerous occasions.[33]

In 64 BC,Syriabecame a province of the Roman Empire, following the conquest byPompey.Roman Syria borderedJudeato the south, Anatolian Greek domains to the north, Phoenicia to the West, and was in constant struggle with Parthians to the East. In 135 AD, Syria-Palaestina became to incorporate the entire Levant and Western Mesopotamia. In 193, the province was divided into Syria proper (Coele-Syria) andPhoenice.Sometime between 330 and 350 (likely c. 341), the province ofEuphratensiswas created out of the territory of Syria Coele and the former realm of Commagene, withHierapolisas its capital.[34]

After c. 415 Syria Coele was further subdivided into Syria I, with the capital remaining atAntioch,and Syria II or Salutaris, with capital atApameaon theOrontes River.In 528,Justinian Icarved out the small coastal provinceTheodoriasout of territory from both provinces.[35]

Bilad al-Sham

[edit]Theregion was annexedto theRashidun Caliphateafter the Muslim victory over theByzantine Empireat theBattle of Yarmouk,and became known as the province ofBilad al-Sham.During theUmayyad Caliphate,the Shām was divided into fivejundsor military districts. They wereJund Dimashq(for the area of Damascus),Jund Ḥimṣ(for the area ofHoms),Jund Filasṭīn(for the area ofPalestine) andJund al-Urdunn(for the area of Jordan). LaterJund Qinnasrînwas created out of part of Jund Hims. The city of Damascus was the capital of the Islamic Caliphate, until the rise of theAbbasid Caliphate.[36][37][38]

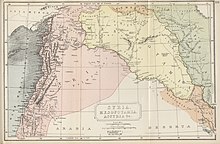

Ottoman Syria

[edit]In the later ages of theOttomantimes, it was divided intowilayahsor sub-provinces the borders of which and the choice of cities as seats of government within them varied over time. The vilayets or sub-provinces of Aleppo, Damascus, and Beirut, in addition to the two special districts ofMount LebanonandJerusalem.Aleppo consisted of northern modern-day Syria plus parts of southern Turkey, Damascus covered southern Syria and modern-day Jordan, Beirut covered Lebanon and the Syrian coast from the port-city ofLatakiasouthward to theGalilee,while Jerusalem consisted of the land south of the Galilee and west of theJordan Riverand theWadi Arabah.

Although the region's population was dominated bySunni Muslims,it also contained sizable populations ofShi'ite,AlawiteandIsmailiMuslims,Syriac Orthodox,Maronite,Greek Orthodox,Roman CatholicsandMelkiteChristians,JewsandDruze.

Arab Kingdom and French occupation

[edit]

TheOccupied Enemy Territory Administration(OETA) was a British, French and Arab military administration over areas of the former Ottoman Empire between 1917 and 1920, during and followingWorld War I.The wave ofArab nationalismevolved towards the creation of the first modern Arab state to come into existence, the HashemiteArab Kingdom of Syriaon 8 March 1920. The kingdom claimed the entire region of Syria whilst exercising control over only the inland region known as OETA East. This led to the acceleration of the declaration of the FrenchMandate for Syria and the Lebanonand BritishMandate for Palestineat the 19–26 April 1920San Remo conference,and subsequently theFranco-Syrian War,in July 1920, in which French armiesdefeatedthe newly proclaimed kingdom andcapturedDamascus, aborting the Arab state.[39]

Thereafter, the French generalHenri Gouraud,in breach of the conditions of the mandate, subdivided theFrench Mandate of Syriainto six states. They were the states ofDamascus(1920),Aleppo(1920),Alawite State(1920),Jabal Druze(1921), the autonomousSanjak of Alexandretta(1921) (modern-dayHatayin Turkey), andGreater Lebanon(1920) which later became the modern country of Lebanon.

In pan-Syrian nationalism

[edit]

The boundaries of the region have changed throughout history, and were last defined in modern times by the proclamation of the short-lived Arab Kingdom of Syria and subsequent definition by French and British mandatory agreement. The area was passed to French and British Mandates followingWorld War Iand divided intoGreater Lebanon,various Syrian-mandate states,Mandatory Palestineand theEmirate of Transjordan.The Syrian-mandate states were gradually unified as theState of Syriaand finally became the independent Syria in 1946. Throughout this period,Antoun Saadehand his party, theSyrian Social Nationalist Party,envisioned "Greater Syria" or "Natural Syria", based on theetymological connection between the name "Syria" and "Assyria",as encompassing theSinai Peninsula,Cyprus, modern Syria, Lebanon, Palestine, Jordan, Iraq, Kuwait, theAhvazregion of Iran, and theKilikianregion of Turkey.[40][41]

Religious significance

[edit]The region has sites that are significant toAbrahamic religions:[1][42][43]

| Place | Description | Image |

|---|---|---|

| Acre | Acre is home to theShrine of Baháʼu'lláh,which is the holiest site for theBaháʼí Faith.[44][45] |  |

| Aleppo | Aleppo is home to aGreat Mosque,which is believed to house the remains ofZechariah,[46]who is revered in bothChristianity[47]andIslam.[48][49] |  |

| Bethlehem | Bethlehem has sites which are significant forJews,ChristiansandMuslims.One of these isRachel's Tomb,which is revered by members of all three faiths. Another is theChurch of the Nativity(of Jesus),[50]revered by Christians, and nearby, theMosque of Omar,revered by Muslims.[51] |  |

| Damascus | TheOld Cityhas aGreat Mosque[52][53][54]which is considered to be one of the largest and best preserved mosques from theUmayyad era.It is believed to house the remains of Zechariah's sonJohn the Baptist,[36][55]who is revered inChristianity[47]andIslam,like his father.[49]The city is also home to theSayyidah Zainab Mosque,the shrine ofZaynab bint Alithe grand-daughter of theIslamic prophetMuhammad,andSayyidah Ruqayya Mosque,the shrine ofRuqayyathe daughter ofHusayn,both sites holy toShia Muslims.[56] |  |

| Haifa | Haifa is where theShrine of the Bábis located. It is holy to the Baháʼí Faith.[42][57]

Nearby isMount Carmel.Being associated with the Biblical figureElijah,it is important to Christians,Druze,Jews and Muslims.[58] |

|

| Hebron | TheOld Cityis home to theCave of the Patriarchs,where theBiblicalfiguresAbraham,his wifeSarah,their sonIsaac,his wifeRebecca,their sonJacob,and his wifeLeahare believed buried, and thus revered by followers of the Abrahamic faiths, including Muslims and Jews.[59][60] |  |

| Hittin | Hittin is near what is believed to near theshrineofShuaib(possiblyJethro). It is holy to Druze and Muslims.[61][62] |  |

| Jericho/ An-Nabi Musa | Near the city of Jericho in the West Bank is the shrine ofNabiMusa(literally:ProphetMoses), which is considered by Muslims to be the burial place ofMoses.[43][63][64] |  |

| Jerusalem | TheOld Cityis home to many sites of seminalreligious importancefor the three major Abrahamic religions—Judaism,Christianity,andIslam.These sites include theTemple Mount,[65][66]Church of the Holy Sepulchre,[67][68]Al-Aqsaand theWestern Wall.[69]It is regarded as the holiest city in Judaism,[70]and the third-holiest in Sunni Islam.[71] |  |

| Mount Gerizim | InSamaritanism,Mount Gerizim is the holiest site on earth, and the location chosen by God to build a temple. In their tradition, it is the oldest and most central mountain in the world, towering above theGreat Floodand providing the first land forNoah’s disembarkation.[72]In their belief, it is also the location whereAbraham almost sacrificed his son Isaac.[73] |  |

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^Hieroglyphic Luwian:𔒂𔒠Sura/i;Greek:Συρία;Classical Syriac:ܣܘܪܝܐ.

- ^In the Hebrew language, mayim (מַיִם) means "water". InGenesis 1:6Elohimseparated the "water from the water". The area above the earth was filled by sky-water (sham-mayim) and the earth below was covered by sea-water (yam-mayim).

References

[edit]- ^abcdMustafa Abu Sway."The Holy Land, Jerusalem and Al-Aqsa Mosque in the Qur'an, Sunnah and other Islamic Literary Source"(PDF).Central Conference of American Rabbis.Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 28 July 2011.

- ^abPfoh, Emanuel (22 February 2016).Syria-Palestine in The Late Bronze Age: An Anthropology of Politics and Power.Routledge.ISBN978-1-3173-9230-9.

- ^abKillebrew, A. E.; Steiner, M. L. (2014).The Oxford Handbook of the Archaeology of the Levant: C. 8000–332 BCE.OUP Oxford. p. 2.ISBN978-0-19-921297-2.

The western coastline and the eastern deserts set the boundaries for the Levant... The Euphrates and the area around Jebel el-Bishrī mark the eastern boundary of the northern Levant, as does the Syrian Desert beyond the Anti-Lebanon range's eastern hinterland and Mount Hermon. This boundary continues south in the form of the highlands and eastern desert regions of Transjordan.

- ^abcdeRollinger, Robert (2006). "The terms" Assyria "and" Syria "again".Journal of Near Eastern Studies.65(4): 284–287.doi:10.1086/511103.S2CID162760021.

- ^abcFrye, R. N. (1992). "Assyria and Syria: Synonyms".Journal of Near Eastern Studies.51(4): 281–285.doi:10.1086/373570.S2CID161323237.

- ^abcdSalibi, Kamal S.(2003).A House of Many Mansions: The History of Lebanon Reconsidered.I.B.Tauris. pp. 61–62.ISBN978-1-86064-912-7.

To theArabs,this same territory, which the Roman Empire considered Arabian, formed part of what they called Bilad al-Sham, which was their own name for Syria. From the classical perspective, however, Syria, including Palestine, formed no more than the western fringes of what was reckoned to be Arabia between the first line of cities and the coast. Since there is no clear dividing line between what is called today theSyrianandArabian deserts,which actually form one stretch of arid tableland, the classical concept of what actually constituted Syria had more to its credit geographically than the vaguer Arab concept of Syria as Bilad al-Sham. Under the Romans, there was actually a province of Syria, with its capital at Antioch, which carried the name of the territory. Otherwise, down the centuries, Syria, like Arabia and Mesopotamia, was no more than a geographic expression. In Islamic times, the Arab geographers used the name arabicized as Suriyah, to denote one special region of Bilad al-Sham, which was the middle section of the valley of the Orontes River, in the vicinity of the towns ofHomsandHama.They also noted that it was an old name for the whole of Bilad al-Sham which had gone out of use. As a geographic expression, however, the name Syria survived in its original classical sense inByzantineand Western European usage, and also in theSyriac literatureof some of theEastern Christian churches,from which it occasionally found its way intoChristian Arabicusage. It was only in the nineteenth century that the use of the name was revived in its modern Arabic form, frequently as Suriyya rather than the older Suriyah, to denote the whole of Bilad al-Sham: first of all in the Christian Arabic literature of the period, and under the influence of Western Europe. By the end of that century it had already replaced the name of Bilad al-Sham even inMuslimArabic usage.

- ^abHerodotus.The History of Herodotus (Rawlinson).

- ^abJoseph, John (2008)."Assyria and Syria: Synonyms?"(PDF).

- ^abTaylor & Francis Group (2003).The Middle East and North Africa 2004.Psychology Press. p. 1015.ISBN978-1-85743-184-1.

- ^abcdeArticle "AL-SHĀM" byC.E. Bosworth,Encyclopaedia of Islam,Volume 9 (1997), page 261.

- ^Thomas Collelo, ed.Lebanon: A Country StudyWashington, Library of Congress, 1987.

- ^abHerodotus."Herodotus VII.63".Fordham University.Archived fromthe originalon 20 February 1999.Retrieved28 May2013.

VII.63: The Assyrians went to war with helmets upon their heads made of brass, and plaited in a strange fashion which is not easy to describe. They carried shields, lances, and daggers very like the Egyptian; but in addition they had wooden clubs knotted with iron, and linen corselets. This people, whom the Hellenes call Syrians, are called Assyrians by the barbarians. The Chaldeans served in their ranks, and they had for commander Otaspes, the son of Artachaeus.

- ^First proposed byTheodor Nöldekein 1881; cf.Harper, Douglas (November 2001)."Syria".Online Etymology Dictionary.Retrieved22 January2013..

- ^Younger, K. Lawson Jr. (7 October 2016).A Political History of the Arameans: From Their Origins to the End of Their Polities (Archaeology and Biblical Studies).Atlanta, GA: SBL Press. p. 551.ISBN978-1589831285.

- ^Tardif, P. (17 September 2017)."'I won't give up': Syrian woman creates doll to help kids raised in conflict ".CBC News.Retrieved6 March2018.

- ^Ali, Maulana Muhammad(2002).The Holy Quran Arabic Text with English Translation, Commentary and comprehensive Introduction(in English and Arabic). The Ahmadiyyah Anjuman Ish'at Islam. p. 1247.ISBN978-0913321058.

- ^"Their protection during their trading caravans in the winter and the summer."[Quran106:2(TranslatedbyShakir)]

- ^Teixidor, Javier (2015).The Pagan God: Popular Religion in the Greco-Roman Near East.Princeton University Press. p. 27.ISBN9781400871391.Retrieved14 August2017.

- ^Beattie, Andrew; Pepper, Timothy (2001).The Rough Guide to Syria.Rough Guides. p. 290.ISBN9781858287188.Retrieved14 August2017.

- ^Dirven, Lucinda (1999).The Palmyrenes of Dura-Europos: A Study of Religious Interaction in Roman Syria.BRILL. p. 76.ISBN978-90-04-11589-7.Retrieved17 July2012.

- ^J.F. Healey (2001).The Religion of the Nabataeans: A Conspectus.BRILL. p. 126.ISBN9789004301481.Retrieved14 August2017.

- ^Caplice, Richard I.; Snell, Daniel C. (1988).Introduction to Akkadian.Gregorian Biblical BookShop. p. 6.ISBN9788876535666.Retrieved14 August2017.

{{cite book}}:CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^Mutlu, Servet."Late Ottoman population and its ethnic distribution".pp. 29–31.Corrected population M8.

- ^Frier, Bruce W. "Demography", in Alan K. Bowman, Peter Garnsey, and Dominic Rathbone, eds.,The Cambridge Ancient History XI: The High Empire, A.D. 70–192,(Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000), 827–54.

- ^Russell, Josiah C. (1985). "The Population of the Crusader States". InSetton, Kenneth M.;Zacour, Norman P.; Hazard, Harry W. (eds.).A History of the Crusades, Volume V: The Impact of the Crusades on the Near East.Madison and London: University of Wisconsin Press. pp. 295–314.ISBN0-299-09140-6.

- ^"Syria Population - Our World in Data".ourworldindata.org.

- ^Haber, Marc; Nassar, Joyce; Almarri, Mohamed A.; Saupe, Tina; Saag, Lehti; Griffith, Samuel J.; Doumet-Serhal, Claude; Chanteau, Julien; Saghieh-Beydoun, Muntaha; Xue, Yali; Scheib, Christiana L.; Tyler-Smith, Chris (2020)."A Genetic History of the Near East from an aDNA Time Course Sampling Eight Points in the Past 4,000 Years".American Journal of Human Genetics.107(1): 149–157.doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2020.05.008.PMC7332655.PMID32470374.

- ^Kennedy, Hugh N.(2007).The Great Arab Conquests: How the Spread of Islam Changed the World We Live In.Da Capo Press. p.376.ISBN978-0-306-81728-1.

- ^Lapidus, Ira M.(13 October 2014) [1988].A History of Islamic Societies(3rd ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 70.ISBN978-0-521-51430-9.

- ^"Christian Population of Middle East in 2014".The Gulf/2000 Project, School of International and Public Affairs of Columbia University. 2017.Retrieved31 August2018.

- ^Shoup, John A (31 October 2011).Ethnic Groups of Africa and the Middle East: An Encyclopedia.Abc-Clio.ISBN978-1-59884-362-0.Retrieved26 May2014.

- ^Pliny (AD 77)(March 1998). "Book 5 Section 66".Natural History.University of Chicago.ISBN84-249-1901-7.

{{cite book}}:CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^A commentary on the Bible,quote "In the time of the Greek predominance it came into use. as it is employed to-day, as the name of the whole western borderland of the Mediterranean, and in the NT it is used several times in that sense (Mt. 4:24, Lk. 2:2, Ac. 15:23,41, 18:18, 21:3, Gal. 1:21)".

- ^Kazhdan, Alexander, ed. (1991).Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium.Oxford University Press. p. 748.ISBN978-0-19-504652-6.

- ^Kazhdan, Alexander, ed. (1991).Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium.Oxford University Press. p. 1999.ISBN978-0-19-504652-6.

- ^abLe Strange, G.(1890).Palestine Under the Moslems: A Description of Syria and the Holy Land from A.D. 650 to 1500.London: Committee of thePalestine Exploration Fund.pp.30–234.OCLC1004386.

- ^Blankinship, Khalid Yahya(1994).The End of the Jihâd State: The Reign of Hishām ibn ʻAbd al-Malik and the Collapse of the Umayyads.Albany, New York: State University of New York Press. pp. 47–50.ISBN0-7914-1827-8.

- ^Cobb, Paul M. (2001).White Banners: Contention in 'Abbāsid Syria, 750–880.Albany, NY: State University of New York Press. pp. 12–182.ISBN0-7914-4880-0.

- ^Itamar Rabinovich,Symposium: The Greater-Syria Plan and the Palestine Problem in The Jerusalem Cathedra (1982), p. 262.

- ^Sa'adeh, Antoun(2004).The Genesis of Nations.Beirut.

{{cite book}}:CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)Translated and Reprinted - ^Ya'ari, Ehud (June 1987)."Behind the Terror".The Atlantic.

- ^abWorld Heritage Committee (2 July 2007)."Convention concerning the protection of the world cultural and natural heritage"(PDF).p. 34.Retrieved8 July2008.

- ^abO'Connor, J. M.(1998).The Holy Land: An Oxford Archaeological Guide from Earliest Times to 1700.Oxford University Press.p. 369.ISBN978-0-1915-2867-5.

- ^National Spiritual Assembly of the United States (January 1966)."Shrine of Bahá'u'lláh".Baháʼí News(418): 4.Retrieved12 August2006.

- ^UNESCO World Heritage Centre (8 July 2008)."Baháʼí Holy Places in Haifa and the Western Galilee".Retrieved8 July2008.

- ^"The Great Mosque of Aleppo | Muslim Heritage".muslimheritage.24 March 2005.Retrieved30 June2016.

- ^abGospel of Luke,1:5–79

- ^Quran19:2–15

- ^abAbdullah Yusuf Ali,The Holy Qur'an: Text, Translation and Commentary,Note.905:"The third group consists not of men of action, but Preachers of Truth, who led solitary lives. Their epithet is:" the Righteous. "They form a connected group round Jesus. Zachariah was the father of John the Baptist, who is referenced as" Elias, which was for to come "(Matt 11:14); and John the Baptist is said to have been present and talked to Jesus at the Transfiguration on the Mount (Matt. 17:3)."

- ^Strickert, Frederick M. (2007).Rachel weeping: Jews, Christians, and Muslims at the Fortress Tomb.Liturgical Press.pp.64–84.ISBN978-0-8146-5987-8.Archived from the original on 3 March 2020.Retrieved3 March2020.

{{cite book}}:CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^Guidetti, Mattia (2016).In the Shadow of the Church: The Building of Mosques in Early Medieval Syria.Arts and Archaeology of the Islamic World (Book 8).Brill;Lam edition. pp. 30–31.ISBN978-9-0043-2570-8.Retrieved9 April2018.

- ^Abu-Lughod, Janet L.(2007)."Damascus".In Dumper, Michael R. T.; Stanley, Bruce E. (eds.).Cities of the Middle East and North Africa: A Historical Encyclopedia.ABC-CLIO.pp. 119–126.ISBN978-1-5760-7919-5.

- ^Birke, Sarah (2 August 2013),Damascus: What's Left,New York Review of Books

- ^Totah, Faedah M. (2009). "Return to the origin: negotiating the modern and unmodern in the old city of Damascus".City & Society.21(1): 58–81.doi:10.1111/j.1548-744X.2009.01015.x.

- ^Burns, 2005, p.88.

- ^Sabrina MERVIN, « Sayyida Zaynab, Banlieue de Damas ou nouvelle ville sainte chiite? », Cahiers d'Etudes sur la Méditerranée Orientale et le monde Turco-Iranien [Online], 22 | 1996, Online since 01 March 2005, connection on 19 October 2014. URL:http://cemoti.revues.org/138

- ^"Beauty of restored Shrine set to dazzle visitors and pilgrims".Baháʼí World News Service. 12 April 2011.Retrieved12 April2011.

- ^Breger, M. J.; Hammer, L.; Reiter, Y. (16 December 2009).Holy Places in the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict: Confrontation and Co-existence.Routledge.pp. 231–246.ISBN978-1-1352-6812-1.

- ^Emmett, Chad F. (2000)."Sharing Sacred Space in the Holy Land".In Murphy, Alexander B.; Johnson, Douglas L.; Haarmann, Viola (eds.).Cultural encounters with the environment: enduring and evolving geographic themes.Rowman & Littlefield.pp. 271–291.ISBN978-0-7425-0106-5.

- ^Gish, Arthur G. (20 December 2018).Hebron Journal: Stories of Nonviolent Peacemaking.Wipf and Stock Publishers.ISBN978-1-5326-6213-3.

- ^Firro, K. M. (1999).The Druzes in the Jewish State: A Brief History.Leiden,The Netherlands:Brill Publishers.pp. 22–240.ISBN90-04-11251-0.

- ^Dana, N. (2003).The Druze in the Middle East: Their Faith, Leadership, Identity and Status.Sussex Academic Press. pp. 28–30.ISBN978-1-9039-0036-9.

- ^Canaan, Tawfiq(1927).Mohammedan Saints and Sanctuaries in Palestine.London: Luzac & Co.

- ^Kupferschmidt, Uri M. (1987).The Supreme Muslim Council: Islam Under the British Mandate for Palestine.Brill.p. 231.ISBN978-9-0040-7929-8.

- ^Rivka, Gonen (2003).Contested Holiness: Jewish, Muslim, and Christian Perspectives on the Temple Mount in Jerusalem.Jersey City, NJ: KTAV Publishing House, Inc. p. 4.ISBN0-88125-798-2.OCLC1148595286.

To the Jews the Temple Mount is the holiest place on Earth, the place where God manifested himself to King David and where two Jewish temples - Solomon's Temple and the Second Temple – were located.

- ^Marshall J., Breger; Ahimeir, Ora (2002).Jerusalem: A City and Its Future.Syracuse University Press. p. 296.ISBN0-8156-2912-5.OCLC48940385.

- ^Strickert, Frederick M. (2007).Rachel weeping: Jews, Christians, and Muslims at the Fortress Tomb.Liturgical Press.pp.64–84.ISBN978-0-8146-5987-8.Archived from the original on 3 March 2020.Retrieved3 March2020.

{{cite book}}:CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^"Church of the Holy Sepulchre, Jerusalem".Jerusalem: Sacred-destinations. 21 February 2010.Retrieved7 July2012.

- ^Frishman, Avraham (2004),Kum Hisalech Be'aretz,Jerusalem

{{citation}}:CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^Since the 10th century BCE:

- "Israel was first forged into a unified nation from Jerusalem some 3,000 years ago, whenKing Davidseized the crown and united thetwelve tribesfrom this city... For a thousand years Jerusalem was the seat of Jewish sovereignty, the household site of kings, the location of its legislative councils and courts. In exile, the Jewish nation came to be identified with the city that had been the site of its ancient capital. Jews, wherever they were, prayed for its restoration. "Roger Friedland, Richard D. Hecht.To Rule Jerusalem,University of California Press, 2000, p. 8.ISBN0-520-22092-7

- "The centrality of Jerusalem to Judaism is so strong that even secular Jews express their devotion and attachment to the city, and cannot conceive of a modern State of Israel without it.... For Jews Jerusalem is sacred simply because it exists... Though Jerusalem's sacred character goes back three millennia...". Leslie J. Hoppe.The Holy City: Jerusalem in the theology of the Old Testament,Liturgical Press, 2000, p. 6.ISBN0-8146-5081-3

- "Ever since King David made Jerusalem the capital of Israel 3,000 years ago, the city has played a central role in Jewish existence." Mitchell Geoffrey Bard,The Complete Idiot's Guide to the Middle East Conflict,Alpha Books, 2002, p. 330.ISBN0-02-864410-7

- "Jerusalem became the center of the Jewish people some 3,000 years ago" Moshe Maoz, Sari Nusseibeh,Jerusalem: Points of Friction – And Beyond,Brill Academic Publishers, 2000, p. 1.ISBN90-411-8843-6

- ^Third-holiest city in Islam:

- Esposito, John L.(2002).What Everyone Needs to Know about Islam.Oxford University Press. p.157.ISBN0-19-515713-3.

The Night Journey made Jerusalem the third holiest city in Islam

- Brown, Leon Carl (2000). "Setting the Stage: Islam and Muslims".Religion and State: The Muslim Approach to Politics.Columbia University Press. p. 11.ISBN0-231-12038-9.

The third holiest city of Islam—Jerusalem—is also very much in the center...

- Hoppe, Leslie J. (2000).The Holy City: Jerusalem in the Theology of the Old Testament.Michael Glazier Books. p. 14.ISBN0-8146-5081-3.

Jerusalem has always enjoyed a prominent place in Islam. Jerusalem is often referred to as the third holiest city in Islam...

- Esposito, John L.(2002).What Everyone Needs to Know about Islam.Oxford University Press. p.157.ISBN0-19-515713-3.

- ^Anderson, Robert T., "Mount Gerizim: Navel of the World",Biblical ArchaeologistVol. 43, No. 4 (Autumn 1980), pp 217–218

- ^UNESCO World Heritage Centre (11 October 2017)."Mount Gerizim and the Samaritans".Retrieved24 December2020.

Citations

[edit]- Dictionary of Modern Written ArabicbyHans Wehr(4th edition, 1994).

- Michael Provence, "TheGreat Syrian Revoltand the Rise of Arab Nationalism ", University of Texas Press, 2005.

Further reading

[edit]- Pipes, Daniel(1990).Greater Syria: the History of an Ambition.New York:Oxford University Press.pp.240.ISBN978-0-19-506022-5.pbk.; illustrated with b&w photos and maps; alternative ISBN on back cover: 0-19-506002-4

- Syria (region)

- Levant

- Geography of Syria

- Geography of Jordan

- Geography of the Middle East

- Historical geography of Syria

- Historical geography of Israel

- History of Palestine (region)

- History of Lebanon

- History of Jordan

- History of Adana Province

- History of Kahramanmaraş Province

- History of Gaziantep Province

- History of Mersin Province

- History of Hatay Province

- History of the Levant

- Historical regions